'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Sunday, 2 January 2022

Saturday, 13 November 2021

Thursday, 21 October 2021

End to China’s estate market boom could spell trouble for the economy

The Kangbashi district of Ordos in Inner Mongolia, famed for being a ‘ghost city’, has since filled up a bit. Photograph: Qilai Shen/Corbis/Getty

The Kangbashi district of Ordos in Inner Mongolia, famed for being a ‘ghost city’, has since filled up a bit. Photograph: Qilai Shen/Corbis/Getty In China today, the buzz is all about how the government there too has stumbled into an energy crisis with widespread power cuts. Yet this and other supply shocks will eventually pass, while the $300bn (£218bn) of debt enveloping China’s second biggest property developer, Evergrande, is of greater significance. It suggests China’s long housing boom is over, and bodes badly for the increasingly troubled economy, with implications for the rest of the world too.

China’s real estate market has been called the most important sector in the world economy. Valued at about $55tn, it is now twice the size of its US equivalent, and four times larger than China’s GDP. Taking into account construction and other property-related goods and services, annual housing activity accounts for about 29% of China’s GDP, far above the 10%-20% typical of most developed nations.

Real estate busts can be as painful as the preceding booms were exuberant. China, however, has only known growth as its previous housing welfare system was transformed from the 1990s onwards. A protracted housing downturn is now poised to add to the Chinese economy’s other mounting headwinds, with significant and unpredictable implications.

The signs were there 10 years ago, when the spotlight fell on China’s “ghost cities”. One of the most publicised was the Kangbashi district of the city of Ordos in Inner Mongolia, famed for its gleaming but empty office blocks and apartment towers, barren boulevards, deserted highways, and vacant shops and plazas. However, ghost cities turned out to be more bad investment than overinvestment. Ordos and similar cities remained eyesores for a while but have since filled up a bit.

Aside from ghost cities, the property sector prospered in the 2000s and 2010s because Beijing not only appeared to want a maturing real-estate market, but promoted it hard to underpin growth and the formation of a propertied, urban middle class. Developers had no qualms about borrowing heavily, because credit was freely available and they felt the government would always support the market if needed.

By the time the pandemic struck in 2020, it had certainly become a case of overinvestment. About a fifth of China’s housing units now lie vacant, often because they are too expensive for the population, 40% of whom earn barely 1,000 yuan (£115) a month. For second and third homes, the vacancy rates are higher still.

Meanwhile, since 2017, Beijing’s attitude towards rampant credit creation and the financialisation of housing – treating it as a commodity rather than as somewhere to live – has undergone a sea change. Xi Jinping told that year’s Communist party congress that “houses are built to be inhabited, not for speculation”, and that action would be taken to curb demand, overbuilding and rising home prices. Tighter mortgage terms and restrictions on multiple-home ownership followed.

Last year, regulators tightened regulations on developers designed to curb debt, preserve cash, and limit overbuilding. The government is sensitive to high housing costs, which are deemed to be excessive and a disincentive to larger family size. The crackdown chimes with its recent “common prosperity” drive, ostensibly designed to address rampant inequality, which has also seen a regulatory clampdown on big tech firms such as Alibaba, Didi and Tencent.

Those changes have exposed the financial fragility of developers and moved the precarious housing bubble centre stage. Even if, as seems likely, the Chinese authorities can keep the fallout from Evergrande from becoming a Lehman-type shock, a downturn in the property and construction sector could well aggravate China’s looming economic slowdown. Some expect China’s growth rate to slide to 1%-2%, for a while at least.

Banks and property companies are likely to restrict building activity and financing as they restructure broken balance sheets and Chinese households will be wary about taking on new mortgages. Household debt has risen from about $2tn in 2010 to more than $10tn last year, with the ratio of debt to disposable income surging to about 130%, significantly higher than in the US. With incomes rising only slowly, especially in the gig or informal economy, which now accounts for about three-fifths of employment, households are likely to remain on the back foot.

Demographics, especially the low 1.3 fertility rate, are also working against the economy. China’s working age and main home buying age groups are declining. The number of prime-age, first-time homebuyers – those in the 25-39 bracket – is set to fall by 25% in the next 20 years from 327 million to 247 million. The urbanisation rate, moreover, which doubled to 64% between 1996 and 2020, is bound to slow. There will be fewer marriages, fewer children and lower household formation.

In the last 10 to 15 years, local and provincial governments could always be relied upon to boost real estate and infrastructure spending to get the economy out of a hole if needed. They are already heavily in debt, however, and under pressure to find resources to support Xi’s “common prosperity” programme.

It is harder to predict what will happen to home prices in China. If they do, for the first time, decline far or over any length of time, expect to see much bigger problems emerge for banks and for consumers as negative wealth effects spread among the urban population.

We do not know how well China will manage to wean itself off real estate construction and services, but it will not be easy or painless. There will be important consequences for China’s economy, possibly its leadership, and the way China projects its influence abroad. Stay tuned.

Monday, 4 October 2021

Wednesday, 29 September 2021

Saturday, 25 September 2021

Thursday, 2 September 2021

Has Covid ended the neoliberal era?

by Adam Tooze in The Guardian

If one word could sum up the experience of 2020, it would be disbelief. Between Xi Jinping’s public acknowledgment of the coronavirus outbreak on 20 January 2020, and Joe Biden’s inauguration as the 46th president of the United States precisely a year later, the world was shaken by a disease that in the space of 12 months killed more than 2.2 million people and rendered tens of millions severely ill. Today the official death tolls stands at 4.51 million. The likely figure for excess deaths is more than twice that number. The virus disrupted the daily routine of virtually everyone on the planet, stopped much of public life, closed schools, separated families, interrupted travel and upended the world economy.

To contain the fallout, government support for households, businesses and markets took on dimensions not seen outside wartime. It was not just by far the sharpest economic recession experienced since the second world war, it was qualitatively unique. Never before had there been a collective decision, however haphazard and uneven, to shut large parts of the world’s economy down. It was, as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) put it, “a crisis like no other”.

Even before we knew what would hit us, there was every reason to think that 2020 might be tumultuous. The conflict between China and the US was boiling up. A “new cold war” was in the air. Global growth had slowed seriously in 2019. The IMF worried about the destabilising effect that geopolitical tension might have on a world economy that was already piled high with debt. Economists cooked up new statistical indicators to track the uncertainty that was dogging investment. The data strongly suggested that the source of the trouble was in the White House. The US’s 45th president, Donald Trump, had succeeded in turning himself into an unhealthy global obsession. He was up for reelection in November and seemed bent on discrediting the electoral process even if it yielded a win. Not for nothing, the slogan of the 2020 edition of the Munich Security Conference – the Davos for national security types – was “Westlessness”.

Apart from the worries about Washington, the clock on the Brexit negotiations was running out. Even more alarming for Europe as 2020 began was the prospect of a new refugee crisis. In the background lurked both the threat of a final grisly escalation in Syria’s civil war and the chronic problem of underdevelopment. The only way to remedy that was to energise investment and growth in the global south. The flow of capital, however, was unstable and unequal. At the end of 2019, half the lowest-income borrowers in sub-Saharan Africa were already approaching the point at which they could no longer service their debts.

The pervasive sense of risk and anxiety that hung around the world economy was a remarkable reversal. Not so long before, the west’s apparent triumph in the cold war, the rise of market finance, the miracles of information technology, and the widening orbit of economic growth appeared to cement the capitalist economy as the all-conquering driver of modern history. In the 1990s, the answer to most political questions had seemed simple: “It’s the economy, stupid.” As economic growth transformed the lives of billions, there was, Margaret Thatcher liked to say, “no alternative”. That is, there was no alternative to an order based on privatisation, light-touch regulation and the freedom of movement of capital and goods. As recently as 2005, Britain’s centrist prime minister Tony Blair could declare that to argue about globalisation made as much sense as arguing about whether autumn should follow summer.

By 2020, globalisation and the seasons were very much in question. The economy had morphed from being the answer to being the question. A series of deep crises – beginning in Asia in the late 90s and moving to the Atlantic financial system in 2008, the eurozone in 2010 and global commodity producers in 2014 – had shaken confidence in market economics. All those crises had been overcome, but by government spending and central bank interventions that drove a coach and horses through firmly held precepts about “small government” and “independent” central banks. The crises had been brought on by speculation, and the scale of the interventions necessary to stabilise them had been historic. Yet the wealth of the global elite continued to expand. Whereas profits were private, losses were socialised. Who could be surprised, many now asked, if surging inequality led to populist disruption? Meanwhile, with China’s spectacular ascent, it was no longer clear that the great gods of growth were on the side of the west.

And then, in January 2020, the news broke from Beijing. China was facing a full-blown epidemic of a novel coronavirus. This was the natural “blowback” that environmental campaigners had long warned us about, but whereas the climate crisis caused us to stretch our minds to a planetary scale and set a timetable in terms of decades, the virus was microscopic and all-pervasive, and was moving at a pace of days and weeks. It affected not glaciers and ocean tides, but our bodies. It was carried on our breath. It would put not just individual national economies but the world’s economy in question.

As it emerged from the shadows, Sars-CoV-2 had the look about it of a catastrophe foretold. It was precisely the kind of highly contagious, flu-like infection that virologists had predicted. It came from one of the places they expected it to come from – the region of dense interaction between wildlife, agriculture and urban populations sprawled across east Asia. It spread, predictably, through the channels of global transport and communication. It had, frankly, been a while coming.

There have been far more lethal pandemics. What was dramatically new about coronavirus in 2020 was the scale of the response. It was not just rich countries that spent enormous sums to support citizens and businesses – poor and middle-income countries were willing to pay a huge price, too. By early April, the vast majority of the world outside China, where it had already been contained, was involved in an unprecedented effort to stop the virus. “This is the real first world war,” said Lenín Moreno, president of Ecuador, one of the hardest-hit countries. “The other world wars were localised in [some] continents with very little participation from other continents … but this affects everyone. It is not localised. It is not a war from which you can escape.”

Lockdown is the phrase that has come into common use to describe our collective reaction. The very word is contentious. Lockdown suggests compulsion. Before 2020, it was a term associated with collective punishment in prisons. There were moments and places where that is a fitting description for the response to Covid. In Delhi, Durban and Paris, armed police patrolled the streets, took names and numbers, and punished those who violated curfews. In the Dominican Republic, an astonishing 85,000 people, almost 1% of the population, were arrested for violating the lockdown.

Even if no violence was involved, a government-mandated closure of all eateries and bars could feel repressive to their owners and clients. But lockdown seems a one-sided way of describing the economic reaction to the coronavirus. Mobility fell precipitately, well before government orders were issued. The flight to safety in financial markets began in late February. There was no jailer slamming the door and turning the key; rather, investors were running for cover. Consumers were staying at home. Businesses were closing or shifting to home working. By mid-March, shutting down became the norm. Those who were outside national territorial space, like hundreds of thousands of seafarers, found themselves banished to a floating limbo.

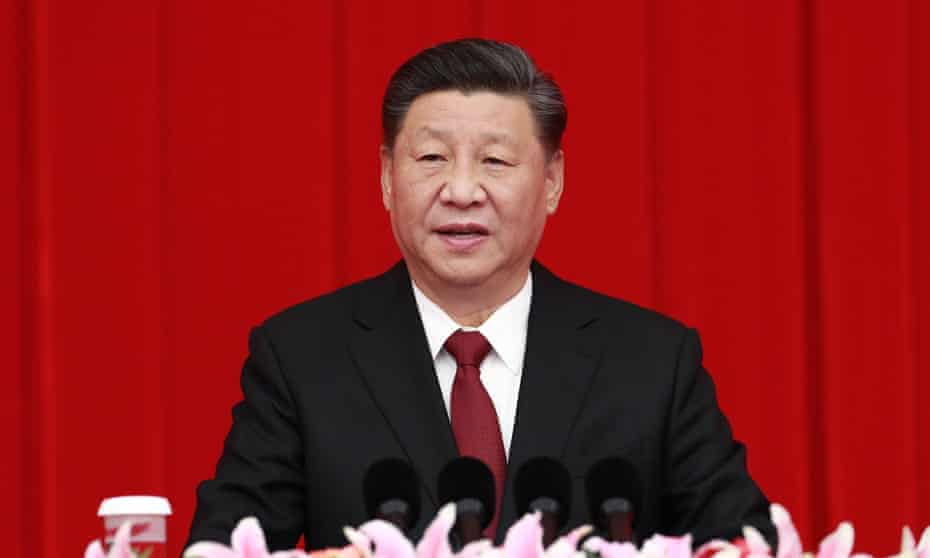

President Xi Jinping in January 2020. Photograph: Nareshkumar Shaganti/Alamy

President Xi Jinping in January 2020. Photograph: Nareshkumar Shaganti/AlamyThe widespread adoption of the term “lockdown” is an index of how contentious the politics of the virus would turn out to be. Societies, communities and families quarrelled bitterly over face masks, social distancing and quarantine. The entire experience was an example on the grandest scale of what the German sociologist Ulrich Beck in the 80s dubbed “risk society”. As a result of the development of modern society, we found ourselves collectively haunted by an unseen threat, visible only to science, a risk that remained abstract and immaterial until you fell sick, and the unlucky ones found themselves slowly drowning in the fluid accumulating in their lungs.

One way to react to such a situation of risk is to retreat into denial. That may work. It would be naive to imagine otherwise. Many pervasive diseases and social ills, including many that cause loss of life on a large scale, are ignored and naturalised, treated as “facts of life”. With regard to the largest environmental risks, notably the climate crisis, one might say that our normal mode of operation is denial and willful ignorance on a grand scale.

Facing up to the pandemic was what the vast majority of people all over the world tried to do. But the problem, as Beck said, is that getting to grips with the really large-scale, all-pervasive risks that modern society generates is easier said than done. It requires agreement on what the risk is. It also requires critical engagement with our own behaviour, and with the social order to which it belongs. It requires a willingness to make political choices about resource distribution and priorities at every level. Such choices clash with the prevalent desire of the last 40 years to depoliticise, to use markets or the law to avoid such decisions. This is the basic thrust behind neoliberalism, or the market revolution – to depoliticise distributional issues, including the very unequal consequences of societal risks, whether those be due to structural change in the global division of labour, environmental damage, or disease.

Coronavirus glaringly exposed our institutional lack of preparation, what Beck called our “organised irresponsibility”. It revealed the weakness of basic apparatuses of state administration, like up-to-date government databases. To face the crisis, we needed a society that gave far greater priority to care. Loud calls issued from unlikely places for a “new social contract” that would properly value essential workers and take account of the risks generated by the globalised lifestyles enjoyed by the most fortunate.

It fell to governments mainly of the centre and the right to meet the crisis. Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and Donald Trump in the US experimented with denial. In Mexico, the notionally leftwing government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador also pursued a maverick path, refusing to take drastic action. Nationalist strongmen such as Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, Narendra Modi in India, Vladimir Putin in Russia, and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey did not deny the virus, but relied on their patriotic appeal and bullying tactics to see them through.

It was the managerial centrist types who were under most pressure. Figures like Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer in the US, or Sebastián Piñera in Chile, Cyril Ramaphosa in South Africa, Emmanuel Macron, Angela Merkel, Ursula von der Leyen and their ilk in Europe. They accepted the science. Denial was not an option. They were desperate to demonstrate that they were better than the “populists”.

To meet the crisis, very middle-of-the-road politicians ended up doing very radical things. Most of it was improvisation and compromise, but insofar as they managed to put a programmatic gloss on their responses – whether in the form of the EU’s Next Generation programme or Biden’s Build Back Better programme in 2020 – it came from the repertoire of green modernisation, sustainable development and the Green New Deal.

The result was a bitter historic irony. Even as the advocates of the Green New Deal, such as Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn, had gone down to political defeat, 2020 resoundingly confirmed the realism of their diagnosis. It was the Green New Deal that had squarely addressed the urgency of environmental challenges and linked it to questions of extreme social inequality. It was the Green New Deal that had insisted that in meeting these challenges, democracies could not allow themselves to be hamstrung by conservative economic doctrines inherited from the bygone battles of the 70s and discredited by the financial crisis of 2008. It was the Green New Deal that had mobilised engaged young citizens on whom democracy, if it was to have a hopeful future, clearly depended.

The Green New Deal had also, of course, demanded that rather than endlessly patching a system that produced and reproduced inequality, instability and crisis, it should be radically reformed. That was challenging for centrists. But one of the attractions of a crisis was that questions of the long-term future could be set aside. The year 2020 was all about survival.

The immediate economic policy response to the coronavirus shock drew directly on the lessons of 2008. Government spending and tax cuts to support the economy were even more prompt. Central bank interventions were even more spectacular. These fiscal and monetary policies together confirmed the essential insights of economic doctrines once advocated by radical Keynesians and made newly fashionable by doctrines such as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). State finances are not limited like those of a household. If a monetary sovereign treats the question of how to organise financing as anything more than a technical matter, that is itself a political choice. As John Maynard Keynes once reminded his readers in the midst of the second world war: “Anything we can actually do we can afford.” The real challenge, the truly political question, was to agree what we wanted to do and to figure out how to do it.

Experiments in economic policy in 2020 were not confined to the rich countries. Enabled by the abundance of dollars unleashed by the Fed, but drawing on decades of experience with fluctuating global capital flows, many emerging market governments, in Indonesia and Brazil for instance, displayed remarkable initiative in response to the crisis. They put to work a toolkit of policies that enabled them to hedge the risks of global financial integration. Ironically, unlike in 2008, China’s greater success in virus control left its economic policy looking relatively conservative. Countries such as Mexico and India, where the pandemic spread rapidly but governments failed to respond with large-scale economic policy, looked increasingly out of step with the times. The year would witness the head-turning spectacle of the IMF scolding a notionally leftwing Mexican government for failing to run a large enough budget deficit.

It was hard to avoid the sense that a turning point had been reached. Was this, finally, the death of the orthodoxy that had prevailed in economic policy since the 80s? Was this the death knell of neoliberalism? As a coherent ideology of government, perhaps. The idea that the natural envelope of economic activity – whether the disease environment or climate conditions – could be ignored or left to markets to regulate was clearly out of touch with reality. So, too, was the idea that markets could self-regulate in relation to all conceivable social and economic shocks. Even more urgently than in 2008, survival dictated interventions on a scale last seen in the second world war.

All this left doctrinaire economists gasping for breath. That in itself is not surprising. The orthodox understanding of economic policy was always unrealistic. In reality, neoliberalism had always been radically pragmatic. Its real history was that of a series of state interventions in the interests of capital accumulation, including the forceful deployment of state violence to bulldoze opposition. Whatever the doctrinal twists and turns, the social realities with which the market revolution had been entwined since the 1970s all endured until 2020. The historic force that finally burst the dykes of the neoliberal order was not radical populism or the revival of class struggle – it was a plague unleashed by heedless global growth and the massive flywheel of financial accumulation.

In 2008, the crisis had been brought on by the overexpansion of the banks and the excesses of mortgage securitisation. In 2020, the coronavirus hit the financial system from the outside, but the fragility that this shock exposed was internally generated. This time it was not banks that were the weak link, but the asset markets themselves. The shock went to the very heart of the system, the market for American Treasuries, the supposedly safe assets on which the entire pyramid of credit is based. If that had melted down, it would have taken the rest of the world with it.

The scale of stabilising interventions in 2020 was impressive. It confirmed the basic insistence of the Green New Deal that if the will was there, democratic states did have the tools they needed to exercise control over the economy. This was, however, a double-edged realisation, because if these interventions were an assertion of sovereign power, they were driven by crisis. As in 2008, they served the interests of those who had the most to lose. This time, not just individual banks but entire markets were declared too big to fail. To break that cycle of crisis and stabilising, and to make economic policy into a true exercise in democratic sovereignty, would require root-and-branch reform. That would require a real power shift, and the odds were stacked against that.

The massive economic policy interventions of 2020, like those of 2008, were Janus-faced. On the one hand, their scale exploded the bounds of neoliberal restraint and their economic logic confirmed the basic diagnosis of interventionist macroeconomics back to Keynes. When an economy was spiralling into recession, one did not have to accept the disaster as a natural cure, an invigorating purge. Instead, prompt and decisive government economic policy could prevent the collapse and forestall unnecessary unemployment, waste and social suffering.

These interventions could not but appear as harbingers of a new regime beyond neoliberalism. On the other hand, they were made from the top down. They were politically thinkable only because there was no challenge from the left and their urgency was impelled by the need to stabilise the financial system. And they delivered. Over the course of 2020, household net worth in the US increased by more than $15tn. Yet that overwhelmingly benefited the top 1%, who owned almost 40% of all stocks. The top 10%, between them, owned 84%. If this was indeed a “new social contract”, it was an alarmingly one-sided affair.

Nevertheless, 2020 was a moment not just of plunder, but of reformist experimentation. In response to the threat of social crisis, new modes of welfare provision were tried out in Europe, the US and many emerging market economies. And in search of a positive agenda, centrists embraced environmental policy and the issue of the climate crisis as never before. Contrary to the fear that Covid-19 would distract from other priorities, the political economy of the Green New Deal went mainstream. “Green Growth”, “Build Back Better”, “Green Deal” – the slogans varied, but they all expressed green modernisation as the common centrist response to the crisis.

Seeing 2020 as a comprehensive crisis of the neoliberal era – with regard to its environmental, social, economic and political underpinnings – helps us find our historical bearings. Seen in those terms, the coronavirus crisis marks the end of an arc whose origin is to be found in the 70s. It might also be seen as the first comprehensive crisis of the age of the Anthropocene – an era defined by the blowback from our unbalanced relationship to nature.

The year 2020 exposed how dependent economic activity was on the stability of the natural environment. A tiny virus mutation in a microbe could threaten the entire world’s economy. It also exposed how, in extremis, the entire monetary and financial system could be directed toward supporting markets and livelihoods. This forced the question of who was supported and how – which workers, which businesses would receive what benefits or which tax break? These developments tore down partitions that had been fundamental to the political economy of the last half-century – lines that divided the economy from nature, economics from social policy and from politics per se. On top of that, there was another major shift, which in 2020 finally dissolved the underlying assumptions of the era of neoliberalism: the rise of China.

When in 2005 Tony Blair scoffed at critics of globalisation, it was their fears that he mocked. He contrasted their parochial anxieties to the modernising energy of Asian nations, for which globalisation offered a bright horizon. The global security threats that Blair recognised, such as Islamic terrorism, were nasty. But they had no hope of actually changing the status quo. Therein lay their suicidal, otherworldly irrationality. In the decade after 2008, it was that confidence in the robustness of the status quo that was lost.

Russia was the first to expose the fact that global economic growth might shift the balance of power. Fuelled by exports of oil and gas, Moscow re-emerged as a challenge to US hegemony. Putin’s threat, however, was limited. China’s was not. In December 2017, the US issued its new National Security Strategy, which for the first time designated the Indo-Pacific as the decisive arena of great power competition. In March 2019, the EU issued a strategy document to the same effect. The UK, meanwhile, performed an extraordinary about-face, from celebrating a new “golden era” of Sino-UK relations in 2015 to deploying an aircraft carrier to the South China Sea.

The military logic was familiar. All great powers are rivals, or at least so goes the logic of “realist” thinking. In the case of China, there was the added factor of ideology. In 2021, the CCP did something its Soviet counterpart never got to do: it celebrated its centenary. While since the 80s it had permitted market-driven growth and private capital accumulation, Beijing made no secret of its adherence to an ideological heritage that ran by way of Marx and Engels to Lenin, Stalin and Mao. Xi Jinping could hardly have been more emphatic about the need to cleave to this tradition, and no clearer in his condemnation of Mikhail Gorbachev for losing hold of the Soviet Union’s ideological compass. So the “new” cold war was really the “old” cold war revived, the cold war in Asia, the one that the west had in fact never won.

There were, however, two major differences dividing the past from the present. The first was the economy. China posed a threat as a result of the greatest economic boom in history. That had hurt some workers in the west in manufacturing, but businesses and consumers across the western world and beyond had profited immensely from China’s development, and stood to profit even more in future. That created a quandary. A revived cold war with China made sense from every vantage point except “the economy, stupid”.

The second fundamental novelty was the global environmental problem, and the role of economic growth in accelerating it. When global climate politics first emerged in its modern form in the 90s, the US was the largest and most recalcitrant polluter. China was poor and its emissions barely figured in the global balance. By 2020, China emitted more carbon dioxide than the US and Europe put together, and the gap was poised to widen at least for another decade. You could no more envision a solution to the climate problem without China than you could imagine a response to the risk of emerging infectious diseases. China was the most powerful incubator of both.

In 2020, the green modernisers of the EU were still trying to resolve this double dilemma in their strategic documents by defining China all at the same time as a systemic rival, a strategic competitor and a partner in dealing with the climate crisis. The Trump administration made life easier for itself by denying the climate problem. But Washington, too, was impaled on the horns of the economic dilemma – between ideological denunciation of Beijing, strategic calculation, long-term corporate investments in China and the president’s desire to strike a quick deal. This was an unstable combination, and in 2020 it tipped. China was redefined as a threat to the US, strategically and economically. In reaction, the intelligence, security and judicial branches of the American government declared economic war on China. By closing markets and blocking the export of microchips and the equipment to make microchips, they set out to sabotage the development of China’s hi-tech sector, the heart of any modern economy.

It was to a degree accidental that this escalation took place when it did. China’s rise was a long-term world historic shift. But Beijing’s success in handling the coronavirus and the assertiveness that it unleashed were a red flag to the Trump administration. Meanwhile, it was growing increasingly clear that the US’s continued global strength in finance, tech and military power rested on domestic feet of clay. As Covid-19 painfully exposed, the US health system was ramshackle and its domestic social safety net left tens of millions at risk of poverty. If Xi’s “China dream” came through 2020 intact, the same cannot be said for its American counterpart.

The general crisis of neoliberalism in 2020 thus had a specific and traumatic significance for the US – and for one part of the American political spectrum in particular. The Republican party and its nationalist and conservative constituencies suffered in 2020 what can best be described as an existential crisis, with profoundly damaging consequences for the American government, for the American constitution and for America’s relations with the wider world. This culminated in the extraordinary period between 3 November 2020 and 6 January 2021, in which Trump refused to concede electoral defeat, a large part of the Republican party actively supported an effort to overturn the election, the social crisis and the pandemic were left unattended to, and finally, on 6 January, the president and other leading figures in his party encouraged a mob invasion of the Capitol.

For good reason, this raises deep concerns about the future of American democracy. And there are elements on the far right of American politics that can fairly be described as fascistoid. But two basic elements were missing from the original fascist equation in the US in 2020. One is total war. Americans remember the civil war and imagine future civil wars to come. They have recently engaged in expeditionary wars that have blown back on American society in militarised policing and paramilitary fantasies. But total war reconfigures society in quite a different way. It constitutes a mass body, not the individualised commandos of 2020.

The other missing ingredient in the classic fascist equation is social antagonism – a threat from the left, whether imagined or real, to the social and economic status quo. As the constitutional storm clouds gathered in 2020, American business aligned massively and squarely against Trump. Nor were the major voices of corporate America afraid to spell out the business case for doing so, including shareholder value, the problems of running companies with politically divided workforces, the economic importance of the rule of law and, astonishingly, the losses in sales to be expected in the event of a civil war.

This alignment of money with democracy in the US in 2020 should be reassuring, but only up to a point. Consider for a second an alternative scenario. What if the virus had arrived in the US a few weeks sooner, the spreading pandemic had rallied mass support for Bernie Sanders and his call for universal health care, and the Democratic primaries had swept an avowed socialist to the head of the ticket rather than Joe Biden? It is not difficult to imagine a scenario in which the full weight of American business was thrown the other way, for all the same reasons, backing Trump in order to ensure that Sanders was not elected. And what if Sanders had in fact won a majority? Then we would have had a true test of the American constitution and the loyalty of the most powerful social interests to it. The fact that we have to contemplate such scenarios is indicative of the extremity of the polycrisis of 2020.

The election of Joe Biden and the fact that his inauguration took place at the appointed time on 21 January 2021 restored a sense of calm. But when Biden boldly declares that “America is back”, it has become increasingly clear that the next question we need to ask is: which America? And back to what? The comprehensive crisis of neoliberalism may have unleashed creative intellectual energy even at the once-dead centre of politics. But an intellectual crisis does not a new era make. If it is energising to discover that we can afford anything we can actually do, it also puts us on the spot. What can and should we actually do? Who, in fact, is the we?

As Britain, the US and Brazil demonstrate, democratic politics is taking on strange and unfamiliar new forms. Social inequalities are more, not less extreme. At least in the rich countries, there is no collective countervailing force. Capitalist accumulation continues in channels that continuously multiply risks. The principal use to which our newfound financial freedom has been put are more and more grotesque efforts at financial stabilisation. The antagonism between the west and China divides huge chunks of the world, as not since the cold war. And now, in the form of Covid, the monster has arrived. The Anthropocene has shown its fangs – on an as yet modest scale. Covid is far from being the worst of what we should expect – 2020 was not the full alert. If we are dusting ourselves off and enjoying the recovery, we should reflect. Around the world the dead are unnumbered, but our best guess puts the figure at 10 million. Thousands are dying every day. And 2020 was a wake-up call.

Wednesday, 28 July 2021

Thursday, 15 July 2021

Monday, 12 July 2021

Saturday, 10 July 2021

Friday, 9 July 2021

Thursday, 17 June 2021

Thursday, 10 June 2021

Government Pensions subject to 'Good Behaviour'

On 31 May, the Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions, which is headed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, issued a gazette notification amending Rule 8 — “Pension subject to future good conduct” — of the Central Civil Services (Pension) Rules 1972. The amendment prohibits retired personnel who have worked in any intelligence or security-related organisation included in the Second Schedule of the Right to Information Act 2005 from publication “of any material relating to and including domain of the organisation, including any reference or information about any personnel and his designation, and expertise or knowledge gained by virtue of working in that organisation”, without prior clearance from the “Head of the Organisation”. An undertaking is also supposed to be signed to the effect that any violation of this rule can lead to withholding of pension in full or in part.

There are 26 organisations included in the Second Schedule of the RTI Act, including the Intelligence Bureau, Research & Analysis Wing, Directorate of Revenue Intelligence, Central Bureau of Investigation, Narcotics Control Bureau, Border Security Force, Central Reserve Police Force, Indo-Tibetan Border Police and Central Industrial Security Force. These organisations are excluded from the RTI Act. Ironically, the armed forces, which are responsible for the external and at times internal security, are covered by the Act.

In 2008, Rule 8 was first amended to make more explicit the existing restrictions under the Official Secrets Act by barring retired officials from publishing without prior permission from Head of the Department any sensitive information, the disclosure of which would “prejudicially affect the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security, strategic, scientific or economic interests of the State or relation with a foreign State or which would lead to incitement of an offence.” An undertaking similar to the present amendment was also required to be signed.

The scope of the 31 May amendment is all-encompassing and its ambiguity leaves it open for vested interpretation and virtually bars retired officers who have served in the above-mentioned organisations from writing or speaking, based on their experience in service or even using the knowledge and expertise acquired after retirement. There is an apprehension that in future, the rules of other government organisations, including the armed forces, may also be amended to incorporate similar provisions.

The motive behind the amendment

All governments are legitimately concerned with safeguarding national security. Almost all countries have laws for the same. However, political dispensations often use these provisions to stifle criticism of the government, particularly by retired government officials who, based on their domain knowledge and experience, enjoy immense credibility with the public.

Originally, Rule 8 allowed withholding/withdrawal of pension or part thereof, permanently/for a specified period if the pensioner was convicted of a serious crime or was found guilty of grave misconduct. “Serious crime” included crime under Official Secrets Act 1923 and “grave misconduct” also covered communication/disclosure of information mentioned in Section 5 of the Act.

There was no requirement of prior permission before publication of any book or article, and prosecution under Official Secrets Act was necessary before any action could be taken. No undertaking was required to be given by the retiree officials. There is no noteworthy case in which this provision was invoked.

The motive behind the 2008 amendment by the UPA and the present amendment by the NDA, was/is to crack down on dissent by retired officials without the due process of law. This, when despite recommendations of the Law Commission and Second Administrative Reforms Commission, no effort has been made to amend the 98-year-old Official Secrets Act to cater for current requirements of national security. The only difference between the two amendments is that the latter makes the rule more absolute by adding the ambiguous rider regarding publication without permission “of any material relating to and including ‘domain of the organisation’, including any reference or information about any personnel and his designation, and expertise or knowledge gained by virtue of working in that organisation.”

The amendment to Rule 8 is unlikely to withstand the scrutiny of law. The Supreme Court and the high courts have repeatedly upheld the principle that “pension is not a bounty, charity or a gratuitous payment but an indefeasible right of every employee”. The government cannot take away the right merely by giving a show cause notice to a retired official for having used “domain knowledge or expertise” while writing an article/book or speaking at any forum. Any application of this amendment will be thrown out by the courts. No wonder that there has been no known application of the amended rule since 2008. There has been no alarming increase in cases under the Official Secrets Act. Between 2014 and 2019, 50 cases have been filed in the country and none against a government official. And if a government official is actually guilty of violating national security, then is withdrawal of pension an adequate punishment?

What does the government then gain by this amendment? Simple, the new amendment acts as deterrent against criticism by retired officials. Which self-respecting retired government official would like to seek permission from her/his former junior or fight a prolonged legal battle to get his pension restored? The government’s will, thus, prevail not by the wisdom of its decision but by default.

Loss to the nation

All major democracies make optimum use of the experience of their retired government officials. While some become part of the government, others contribute by educating the public and throwing up new ideas/suggestions for the consideration of the government. The domain expert keeps a check on a majoritarian government facing a weak opposition by publicly speaking and writing. All governments try to hide failures and scrutiny for inefficiency. With a weak opposition and government-friendly media, the Bharatiya Janata Party dispensation is more worried about the perceived threat from the retired officials with domain expertise than an ill-informed opposition.

Given the Modi government’s obsession with respect to national security and its lackadaisical performance in its management, it is my view that in the near future, the government will incorporate similar provision in the pension rules of other government departments and the armed forces.

A case in point is the attempt by the Modi government to deny/obfuscate the intelligence failure and the preemptive Chinese intrusions. To date no formal briefing has been given about the actual situation in Eastern Ladakh. Doctored information has been fed to the media through leaks by government/military officials. Three retired defence officers, including the author, brought the real picture before the public through articles and media interviews. All were careful to safeguard operational security. A concerted campaign was launched to discredit these retired officers through government-friendly media and pliant defence analysts until the events overtook their detractors to prove them right. The author extensively used his knowledge of the terrain in Eastern Ladakh to bring the truth before the public. In a similar situation in future, these officers may well be battling in courts to safeguard their pensions.

Imagine a situation that in future when no historical accounts of our wars, counter insurgency/terrorism campaigns and communal riots can be written by retired government and armed forces officers. No retired official will be eligible to head our security related thinks tanks or speak in international forums about our experience. Despite provision of Section 8(3) of the RTI Act to declassify documents after 20 years, the government never does so except to score political points as in the case of Netaji Files.

The amendment to Rule 8 of Central Civil Services (Pension) Rules 1972 is nothing more than a blatant, overarching and draconian gag order against retired officials to manage the public narrative for political interests under the garb of safeguarding national security.

It safeguards the interests of the political dispensation and not the nation. It must be challenged in the courts and in the interim disregarded with contempt.

Sunday, 23 May 2021

Monday, 17 May 2021

Why the suspicion on China’s Wuhan lab virus is growing

Tara Kartha in The Print

It’s been nearly eighteen months since the coronavirus brought the world on its knees, with India in the middle of a deadly second wave that is claiming 4,000 lives daily on an average. No one can tell when this will end. But it is possible to probe how this catastrophe began, and China’s role in it. Fortunately, even as cover ups go on. Several reports are out in the public domain and anybody who isn’t afraid of speaking the truth should be able to connect the dots.

One report out is that of the Independent Panel, set up by a resolution of the 73rd World Health Assembly. The specific mission of the committee was to review the response of the World Health Organization (WHO) to the Covid outbreak and the timelines relevant. In other words, it was never meant to be an inquisition on China. And it wasn’t. Not by a long chalk. It went around the core question of the origin of the virus, even while indulging in what seems to be pure speculation. Then there are two recent publications investigating the origin of the virus, which are worthy of note. Neither are written by sage scientists, but by analysts viewing the whole sequence of events through the prism of intelligence. Which means that these efforts skip the big words, and get to the facts. Collate all these different sources, add a little more of the background colour, and you start to get the big picture.

Is this biological warfare?

The need to find out the truth becomes urgent as the situation worsens, for instance with dangerously high death rates in Aligarh Muslim University, where there is now speculation whether the deaths could be linked to a separate strain. There are arguments that India’s second wave could be a deliberate one, especially since the ‘double mutant’ has not hit any of its neighbours. Such speculation is likely to rise, given that China has now effectively closed any possibility of withdrawal from Ladakh, and the Chinese economy goes from strength to strength, growing a record 18.3 per cent in the first quarter of the new financial year. Unsurprisingly, even world leaders, like Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro, have linked the pandemic to biological warfare.

Arising from this is the biggest potential danger: someone may decide to respond in kind in a bid to fix Beijing. That’s how intelligence operations work. After all, major countries haven’t been funding their top secret labs for nothing. In any scenario, there’s some serious trouble ahead, especially since the Narendra Modi government seems to be more intent on playing down the crisis than addressing it.

The Independent Panel

The panel’s mandate is set out clearly in the May 2020 resolution, which calls for “a stepwise process of impartial, independent and comprehensive evaluation…to review experience gained and lessons learned from the WHO-coordinated international health response to COVID-19…” and thereafter provide recommendations. This the panel undoubtedly did.

The 13-member panel included former Prime Minister of New Zealand Helen Clark, former President of Liberia who has core expertise in setting up health care after Ebola, an award winning feminist, a former WHO bureaucrat, and a former Indian health secretary, who had six months experience in handling the first Covid wave, was on innumerable panels on health, and in the manner of civil servants in this country, also did a stint in the Ministry of Defence, not to mention the World Bank. The Indian representative certainly gives the whole exercise the imprimatur of legality, given hostile India-China relations. And finally, Zhong Nanshan who was advisor to the Chinese government during the Wuhan outbreak, and who received the highest State honour of the Medal of the Republic from his President—Xinhua describes him as a “brave and outspoken” doctor.

The WHO also lists Peng Liyuan as a Goodwill Ambassador, describing her as a famous opera singer. She is the wife of President Xi Jinping. It’s,therefore, entirely unsurprising that while the panel diligently shows WHO the sources of early warning, it makes a vague case on the origins of the virus, noting that while a species of bat was “probably” the host, the intermediate cycle is unknown. Most astonishingly, the committee states that the virus “may already have been in circulation outside China in the last months of 2019”. No evidence for that either. The overall tenor of the report is that it would take years to sort all this out.

There is only one paragraph of note from the point of view of those seeking the truth.

The panel’s report states that less than 55–60 per cent of early cases had been exposed to the wet markets, and that the area merely “amplified” the virus. In other words, the market, with its hundreds of exotic wildlife, could not have been the source. It, however, carefully notes that the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) sequenced the entire genome of the virus almost within weeks, and later provided this to a public access source. The report praises the diligence of clinicians who managed to isolate the virus within a short time. That’s wonderful all right. No question. But it doesn’t at all address the question whether those diligent researchers were also experimenting on the virus.

That troubling question

These assessments by the Independent Panel are now, however, being questioned, leading to bits of intelligence being pieced together from within a country that would put the term ‘Iron curtain’ to shame. An earlier WHO study on the virus’ origin was roundly condemned by a group of countries,including the US, Australia, Canada and others (not India) as being duplicitous in the extreme.

In January 2021, the US Department of State released a Fact Sheet on activity of WIV, which is entirely based on intelligence. That factsheet is damning, indicating that several researchers at the institute had fallen ill with characteristics of the Covid virus, thus showing up senior Chinese researcher Shi Zhengli’s claim that there was “zero infection” in the lab. The lab was the centre of research of the SARS virus since its first outbreak, including on ‘RaTG13’ virus found in bats, and which is 96 per cent similar to the present virus SARS-COV-2. Worst, it also pointed out that “the United States has determined that the WIV has collaborated on publications and secret projects with China’s military. The WIV has engaged in classified research, including laboratory animal experiments, on behalf of the Chinese military since at least 2017”.

That’s intelligence. Now for the analysis — the two recent publications probing the virus’ origin.

Disaggregating the facts

One analytical article is published in the prestigious Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Another is a paper by the equally reputed Begin Sadat Centre for Strategic Studies. Both are a careful collation of facts, and establish the following.

The paper by Begin Sadat Centre brings out additional information that bolsters the US Fact Sheet. It appears that the US had been able to get a ‘source’ from WIV directly, and that another Chinese scientist had defected to an unknown European country. That led directly to information on the military side of the programme. The study also quotes David Asher, who led the Department of State investigation. Asher observes that the WIV had two campuses, not one, as popularly believed. This was known by the Indian authorities for years, but does not seem to have been put about. Asher also adds that all mention of the SARS virus was dropped from the institute’s publicly admitted biological “defence programmes” by 2017 at the same time when the Level 4 lab kicked off operations.

Even more surprising was that an adjacent facility had already administered vaccines to its senior faculty in March 2020 itself. That doesn’t suggest an accident. That suggests a program that was designed to kill, and for which vaccines were already under research. Then there damning studies stated: “There are plenty of indications in the sequence itself that [the initial pandemic virus] may have been synthetically altered. It has the backbone of a bat [coronavirus], combined with a pangolin receptor binder, combined with some sort of humanized mice transceptor. These things don’t actually make sense (and) …..the odds this could be natural are very low… [but this is attainable] through deliberate scientific ‘gain of function research” that was going on at the WIV.

There is no doubt that ‘gain of function’ research is practised in biological research labs world over, resulting in, sometimes, dangerous incidents. This type of research involves in-crossing viruses, ostensibly to gain knowledge on how to battle the disease from within. In these cases, it’s almost impossible to decide where the ‘defence’ aspect leaches into an offensive capability. That these findings were from US scientists who were ‘fearful’ of being quoted shows not just the extent of Beijing’s clout in university research and funding, but also a high degree of restraint. Biological research is almost never talked about.

The denials begin

Biological research and the secrecy around it is the aspect of focus in Nicholas Wade’s article published in Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. As he writes, from the beginning, there was denial at the highest levels from some unexpected quarters. The first was in The Lancet— one of the oldest journals of medical research—by a group of authors in March 2020, when the pandemic had just broken out. Even to a layman, it would have seemed that it was far too early for the group of authors to contemptuously dismiss ‘conspiracy theories’ that the virus was not of a natural origin.

It turns out that The Lancet letter was drafted by Peter Daszak, President of the EcoHealth Alliance of New York, who’s organisation funded corona virus research at the Wuhan lab. As is pointed out in Wade’s article, any revelation of such a connection would have been criminal to say the least, if it was proved that the virus did escape from the lab. Unsurprisingly, Daszak was also part of the WHO team investigating the origins of the virus.

Another burst of outrage came from a group of professors who also hurried to disprove, in an article, the ‘lab created’ theory on the grounds – simply put – that it was not of the most probably calculated design. The lead author Kristian G Anderson is from the Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, which specialises in biomedical research. It also has partnerships with Chinese labs and pharma companies. None of that is criminal. Especially when Scrippsis already in financial distress at the time. Besides, such collaborations are not restricted to just US labs. See, for instance, an account of Australian doctor Dominic Dwyer, who was part of the first WHO study, and who dismissed without any evidence presented that the virus had leaked from a lab.

Dwyer’s claim that the Wuhan lab seems to have been run well, and that nobody from the facility seemed to have fallen sick has now been disputed. Evidence of a dangerous virus escaping a lab – as it has in the past on what he calls “rare” occasions – would mean a death blow to labs everywhere. Funding is, after all, hard to come by. Then there is the nice hard cash involved. The Harvard professor Dr Charles Leiber who was arrested, together with two other Chinese, for collaborating quietly with the Wuhan University of Technology (WUT), was being paid roughly $50,000 per month, living expenses of up to 1,000,000 Chinese Yuan (approximately $158,000) and awarded $1.5 million to establish a research lab at WUT. He was also asked to ‘cultivate’ young teachers and Ph.D. students by organising international conferences.

It’s all very pally and friendly, and a lot of money is involved. The end result? A virus out of hell, that seems not to affect the Chinese as its economy powers ahead and shifts its weight more comfortably into its rising position in the global order.