'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label secret. Show all posts

Showing posts with label secret. Show all posts

Sunday, 10 July 2022

Friday, 21 January 2022

Pakistan's Secretive National Security Policy

Najam Sethi in The Friday Times

The PTI government claims to have formulated a National Security Policy after consulting key stakeholders, including hundreds of intellectuals, experts, businessmen, teachers and students. Unfortunately, however, opposition political parties and leaders were kept out of the loop and parliamentarians, even on the treasury benches, were all but ignored. To top it, the policy is classified as “Secret”. We have only been told that “traditional security” is to buttressed by “human security” by increasing the size of the pie that is to be distributed among these two categories. But not to worry. We already know what our National Security Policy has been for over seven decades and we are not shy of asking how and why the new policy should deviate from established wisdom.

Pakistan’s birth is rooted in the biggest mass migration in world history, unprecedented communal violence, and war over Kashmir. In fact, India’s political leaders wasted no time in loudly proclaiming that the new state of Pakistan would be reabsorbed into India before long. Thus insecurity was built into the genetic structure of the new nation and state and over 70% of the country’s first budget was immediately earmarked for military defense and security. The inherited colonial civil-military bureaucracy – that was more developed, organised and cohesive than the indigenous politicians and political parties – now seized the commanding heights of state and society, centralizing power in Governors-General (Ghulam Mohammad, Khjwaja Nazimuddin) and Presidents (Generals Sikander Mirza and Ayub Khan) and signing strategic defense pacts (CENTO, SEATO, BAGHDAD PACT) with the US (ostensibly against communism but in reality to bolster military defenses against India). Thus was born a National Security State based on three national security pillars: Distrust of, and enmity with, India (“unfinished business of partition” pegged to Kashmir); centralization of power via guided “basic democrats” under General Ayub; and dependence on the US for military and economic aid.

This centralized national security state system broke down in 1971 after the break-up of Pakistan following military defeat, leading to civilian assertion under Z A Bhutto and the first democratic constitution of 1973. But the Empire hit back in 1977 with the imposition of martial law, a presidential non-party system under General Zia ul Haq and return to the American camp in the 1980s. The system received a jolt in 1988 with the unexpected exit of General Zia ul Haq but recouped under President Ghluam Ishaq Khan and General Aslam Beg into a hybrid-constitutional system that enabled a strong military nominee or ally as President with the power to dismiss an elected prime minister and parliament (three times in the 1990s). Benazir Bhutto tried to build peace with Rajiv Gandhi but was declared a national security risk and booted out in 1990. The civilian impulse was restrained throughout the 1990s by periodic sackings and rigged elections. It was finally thwarted in 1999 when Nawaz Sharif clutched at bus diplomacy to build “peace” with India and General Musharraf put paid to it by adventuring in Kargil, overthrowing and exiling him, and ruling like a dictator for eight years on the back of billions of dollars in American military and economic aid for abetting its war in Afghanistan. An unexpected mass resistance sparked by a maverick judge, Iftikhar Chaudhry, ended his rule and ushered in the civilians again, but not before they paid the price of Benazir Bhutto’s life. Asif Zardari’s term was blackballed by Mumbai and Memogate, including the sacking of his prime minister Yousaf Raza Gillani; Nawaz’s rule was undermined by surrogate Dharnas, export of jihadis to India and accusations of sleeping with the enemy, finally coming to an end on the basis of a Joint Investigation Team answering to the brass.

This National Security paradigm was revived with the installation of Imran Khan in 2018 and the incarceration and victimisation of Asif Zardari and Nawaz Sharif. But the loss of American goodwill and aid, coupled with the failure of Imran Khan to provide a modicum of governance, has eroded the prospects of economic revival and legitimacy of the hybrid system, discrediting its manufacturers. Meanwhile, the conventional military balance with the old enemy India has fast deteriorated and, faced with the challenge of both legitimacy and feasibility of the hybrid system, the National Security Establishment has been compelled to return to the drawing board and review its National Security Policy.

Perforce, a new National Security Policy has to be fashioned to withstand the loss of American aid and goodwill; to restore representative and credible legitimacy to the political system; and to step back from perennial conflict with India over Kashmir. The trillion dollar question is how. Only a massive transfer of wealth from the super-rich rentier classes to the poor, and a return to a representative civilian system of governance, will stem the rising economic and political discontent and religious militancy that threatens to overwhelm the state; only a prolonged period of peace with India and a profound retreat from militarism will yield the required space in which to accomplish this task. But any overnight attempt to stand the old National Security Policy on its head may unleash a formidable backlash from vested stakeholders among the institutions, groups and classes that have benefited from it for seven decades.

That is why the new National Security Policy is top secret, and jargon and generalities have been profusely sprinkled on its public version to obscure its true content and challenge.

The PTI government claims to have formulated a National Security Policy after consulting key stakeholders, including hundreds of intellectuals, experts, businessmen, teachers and students. Unfortunately, however, opposition political parties and leaders were kept out of the loop and parliamentarians, even on the treasury benches, were all but ignored. To top it, the policy is classified as “Secret”. We have only been told that “traditional security” is to buttressed by “human security” by increasing the size of the pie that is to be distributed among these two categories. But not to worry. We already know what our National Security Policy has been for over seven decades and we are not shy of asking how and why the new policy should deviate from established wisdom.

Pakistan’s birth is rooted in the biggest mass migration in world history, unprecedented communal violence, and war over Kashmir. In fact, India’s political leaders wasted no time in loudly proclaiming that the new state of Pakistan would be reabsorbed into India before long. Thus insecurity was built into the genetic structure of the new nation and state and over 70% of the country’s first budget was immediately earmarked for military defense and security. The inherited colonial civil-military bureaucracy – that was more developed, organised and cohesive than the indigenous politicians and political parties – now seized the commanding heights of state and society, centralizing power in Governors-General (Ghulam Mohammad, Khjwaja Nazimuddin) and Presidents (Generals Sikander Mirza and Ayub Khan) and signing strategic defense pacts (CENTO, SEATO, BAGHDAD PACT) with the US (ostensibly against communism but in reality to bolster military defenses against India). Thus was born a National Security State based on three national security pillars: Distrust of, and enmity with, India (“unfinished business of partition” pegged to Kashmir); centralization of power via guided “basic democrats” under General Ayub; and dependence on the US for military and economic aid.

This centralized national security state system broke down in 1971 after the break-up of Pakistan following military defeat, leading to civilian assertion under Z A Bhutto and the first democratic constitution of 1973. But the Empire hit back in 1977 with the imposition of martial law, a presidential non-party system under General Zia ul Haq and return to the American camp in the 1980s. The system received a jolt in 1988 with the unexpected exit of General Zia ul Haq but recouped under President Ghluam Ishaq Khan and General Aslam Beg into a hybrid-constitutional system that enabled a strong military nominee or ally as President with the power to dismiss an elected prime minister and parliament (three times in the 1990s). Benazir Bhutto tried to build peace with Rajiv Gandhi but was declared a national security risk and booted out in 1990. The civilian impulse was restrained throughout the 1990s by periodic sackings and rigged elections. It was finally thwarted in 1999 when Nawaz Sharif clutched at bus diplomacy to build “peace” with India and General Musharraf put paid to it by adventuring in Kargil, overthrowing and exiling him, and ruling like a dictator for eight years on the back of billions of dollars in American military and economic aid for abetting its war in Afghanistan. An unexpected mass resistance sparked by a maverick judge, Iftikhar Chaudhry, ended his rule and ushered in the civilians again, but not before they paid the price of Benazir Bhutto’s life. Asif Zardari’s term was blackballed by Mumbai and Memogate, including the sacking of his prime minister Yousaf Raza Gillani; Nawaz’s rule was undermined by surrogate Dharnas, export of jihadis to India and accusations of sleeping with the enemy, finally coming to an end on the basis of a Joint Investigation Team answering to the brass.

This National Security paradigm was revived with the installation of Imran Khan in 2018 and the incarceration and victimisation of Asif Zardari and Nawaz Sharif. But the loss of American goodwill and aid, coupled with the failure of Imran Khan to provide a modicum of governance, has eroded the prospects of economic revival and legitimacy of the hybrid system, discrediting its manufacturers. Meanwhile, the conventional military balance with the old enemy India has fast deteriorated and, faced with the challenge of both legitimacy and feasibility of the hybrid system, the National Security Establishment has been compelled to return to the drawing board and review its National Security Policy.

Perforce, a new National Security Policy has to be fashioned to withstand the loss of American aid and goodwill; to restore representative and credible legitimacy to the political system; and to step back from perennial conflict with India over Kashmir. The trillion dollar question is how. Only a massive transfer of wealth from the super-rich rentier classes to the poor, and a return to a representative civilian system of governance, will stem the rising economic and political discontent and religious militancy that threatens to overwhelm the state; only a prolonged period of peace with India and a profound retreat from militarism will yield the required space in which to accomplish this task. But any overnight attempt to stand the old National Security Policy on its head may unleash a formidable backlash from vested stakeholders among the institutions, groups and classes that have benefited from it for seven decades.

That is why the new National Security Policy is top secret, and jargon and generalities have been profusely sprinkled on its public version to obscure its true content and challenge.

Thursday, 10 June 2021

Government Pensions subject to 'Good Behaviour'

Lt. Gen. H.S Panag (retd.) in The Print

On 31 May, the Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions, which is headed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, issued a gazette notification amending Rule 8 — “Pension subject to future good conduct” — of the Central Civil Services (Pension) Rules 1972. The amendment prohibits retired personnel who have worked in any intelligence or security-related organisation included in the Second Schedule of the Right to Information Act 2005 from publication “of any material relating to and including domain of the organisation, including any reference or information about any personnel and his designation, and expertise or knowledge gained by virtue of working in that organisation”, without prior clearance from the “Head of the Organisation”. An undertaking is also supposed to be signed to the effect that any violation of this rule can lead to withholding of pension in full or in part.

There are 26 organisations included in the Second Schedule of the RTI Act, including the Intelligence Bureau, Research & Analysis Wing, Directorate of Revenue Intelligence, Central Bureau of Investigation, Narcotics Control Bureau, Border Security Force, Central Reserve Police Force, Indo-Tibetan Border Police and Central Industrial Security Force. These organisations are excluded from the RTI Act. Ironically, the armed forces, which are responsible for the external and at times internal security, are covered by the Act.

In 2008, Rule 8 was first amended to make more explicit the existing restrictions under the Official Secrets Act by barring retired officials from publishing without prior permission from Head of the Department any sensitive information, the disclosure of which would “prejudicially affect the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security, strategic, scientific or economic interests of the State or relation with a foreign State or which would lead to incitement of an offence.” An undertaking similar to the present amendment was also required to be signed.

The scope of the 31 May amendment is all-encompassing and its ambiguity leaves it open for vested interpretation and virtually bars retired officers who have served in the above-mentioned organisations from writing or speaking, based on their experience in service or even using the knowledge and expertise acquired after retirement. There is an apprehension that in future, the rules of other government organisations, including the armed forces, may also be amended to incorporate similar provisions.

The motive behind the amendment

All governments are legitimately concerned with safeguarding national security. Almost all countries have laws for the same. However, political dispensations often use these provisions to stifle criticism of the government, particularly by retired government officials who, based on their domain knowledge and experience, enjoy immense credibility with the public.

Originally, Rule 8 allowed withholding/withdrawal of pension or part thereof, permanently/for a specified period if the pensioner was convicted of a serious crime or was found guilty of grave misconduct. “Serious crime” included crime under Official Secrets Act 1923 and “grave misconduct” also covered communication/disclosure of information mentioned in Section 5 of the Act.

There was no requirement of prior permission before publication of any book or article, and prosecution under Official Secrets Act was necessary before any action could be taken. No undertaking was required to be given by the retiree officials. There is no noteworthy case in which this provision was invoked.

The motive behind the 2008 amendment by the UPA and the present amendment by the NDA, was/is to crack down on dissent by retired officials without the due process of law. This, when despite recommendations of the Law Commission and Second Administrative Reforms Commission, no effort has been made to amend the 98-year-old Official Secrets Act to cater for current requirements of national security. The only difference between the two amendments is that the latter makes the rule more absolute by adding the ambiguous rider regarding publication without permission “of any material relating to and including ‘domain of the organisation’, including any reference or information about any personnel and his designation, and expertise or knowledge gained by virtue of working in that organisation.”

The amendment to Rule 8 is unlikely to withstand the scrutiny of law. The Supreme Court and the high courts have repeatedly upheld the principle that “pension is not a bounty, charity or a gratuitous payment but an indefeasible right of every employee”. The government cannot take away the right merely by giving a show cause notice to a retired official for having used “domain knowledge or expertise” while writing an article/book or speaking at any forum. Any application of this amendment will be thrown out by the courts. No wonder that there has been no known application of the amended rule since 2008. There has been no alarming increase in cases under the Official Secrets Act. Between 2014 and 2019, 50 cases have been filed in the country and none against a government official. And if a government official is actually guilty of violating national security, then is withdrawal of pension an adequate punishment?

What does the government then gain by this amendment? Simple, the new amendment acts as deterrent against criticism by retired officials. Which self-respecting retired government official would like to seek permission from her/his former junior or fight a prolonged legal battle to get his pension restored? The government’s will, thus, prevail not by the wisdom of its decision but by default.

Loss to the nation

All major democracies make optimum use of the experience of their retired government officials. While some become part of the government, others contribute by educating the public and throwing up new ideas/suggestions for the consideration of the government. The domain expert keeps a check on a majoritarian government facing a weak opposition by publicly speaking and writing. All governments try to hide failures and scrutiny for inefficiency. With a weak opposition and government-friendly media, the Bharatiya Janata Party dispensation is more worried about the perceived threat from the retired officials with domain expertise than an ill-informed opposition.

Given the Modi government’s obsession with respect to national security and its lackadaisical performance in its management, it is my view that in the near future, the government will incorporate similar provision in the pension rules of other government departments and the armed forces.

A case in point is the attempt by the Modi government to deny/obfuscate the intelligence failure and the preemptive Chinese intrusions. To date no formal briefing has been given about the actual situation in Eastern Ladakh. Doctored information has been fed to the media through leaks by government/military officials. Three retired defence officers, including the author, brought the real picture before the public through articles and media interviews. All were careful to safeguard operational security. A concerted campaign was launched to discredit these retired officers through government-friendly media and pliant defence analysts until the events overtook their detractors to prove them right. The author extensively used his knowledge of the terrain in Eastern Ladakh to bring the truth before the public. In a similar situation in future, these officers may well be battling in courts to safeguard their pensions.

Imagine a situation that in future when no historical accounts of our wars, counter insurgency/terrorism campaigns and communal riots can be written by retired government and armed forces officers. No retired official will be eligible to head our security related thinks tanks or speak in international forums about our experience. Despite provision of Section 8(3) of the RTI Act to declassify documents after 20 years, the government never does so except to score political points as in the case of Netaji Files.

The amendment to Rule 8 of Central Civil Services (Pension) Rules 1972 is nothing more than a blatant, overarching and draconian gag order against retired officials to manage the public narrative for political interests under the garb of safeguarding national security.

It safeguards the interests of the political dispensation and not the nation. It must be challenged in the courts and in the interim disregarded with contempt.

On 31 May, the Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions, which is headed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, issued a gazette notification amending Rule 8 — “Pension subject to future good conduct” — of the Central Civil Services (Pension) Rules 1972. The amendment prohibits retired personnel who have worked in any intelligence or security-related organisation included in the Second Schedule of the Right to Information Act 2005 from publication “of any material relating to and including domain of the organisation, including any reference or information about any personnel and his designation, and expertise or knowledge gained by virtue of working in that organisation”, without prior clearance from the “Head of the Organisation”. An undertaking is also supposed to be signed to the effect that any violation of this rule can lead to withholding of pension in full or in part.

There are 26 organisations included in the Second Schedule of the RTI Act, including the Intelligence Bureau, Research & Analysis Wing, Directorate of Revenue Intelligence, Central Bureau of Investigation, Narcotics Control Bureau, Border Security Force, Central Reserve Police Force, Indo-Tibetan Border Police and Central Industrial Security Force. These organisations are excluded from the RTI Act. Ironically, the armed forces, which are responsible for the external and at times internal security, are covered by the Act.

In 2008, Rule 8 was first amended to make more explicit the existing restrictions under the Official Secrets Act by barring retired officials from publishing without prior permission from Head of the Department any sensitive information, the disclosure of which would “prejudicially affect the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security, strategic, scientific or economic interests of the State or relation with a foreign State or which would lead to incitement of an offence.” An undertaking similar to the present amendment was also required to be signed.

The scope of the 31 May amendment is all-encompassing and its ambiguity leaves it open for vested interpretation and virtually bars retired officers who have served in the above-mentioned organisations from writing or speaking, based on their experience in service or even using the knowledge and expertise acquired after retirement. There is an apprehension that in future, the rules of other government organisations, including the armed forces, may also be amended to incorporate similar provisions.

The motive behind the amendment

All governments are legitimately concerned with safeguarding national security. Almost all countries have laws for the same. However, political dispensations often use these provisions to stifle criticism of the government, particularly by retired government officials who, based on their domain knowledge and experience, enjoy immense credibility with the public.

Originally, Rule 8 allowed withholding/withdrawal of pension or part thereof, permanently/for a specified period if the pensioner was convicted of a serious crime or was found guilty of grave misconduct. “Serious crime” included crime under Official Secrets Act 1923 and “grave misconduct” also covered communication/disclosure of information mentioned in Section 5 of the Act.

There was no requirement of prior permission before publication of any book or article, and prosecution under Official Secrets Act was necessary before any action could be taken. No undertaking was required to be given by the retiree officials. There is no noteworthy case in which this provision was invoked.

The motive behind the 2008 amendment by the UPA and the present amendment by the NDA, was/is to crack down on dissent by retired officials without the due process of law. This, when despite recommendations of the Law Commission and Second Administrative Reforms Commission, no effort has been made to amend the 98-year-old Official Secrets Act to cater for current requirements of national security. The only difference between the two amendments is that the latter makes the rule more absolute by adding the ambiguous rider regarding publication without permission “of any material relating to and including ‘domain of the organisation’, including any reference or information about any personnel and his designation, and expertise or knowledge gained by virtue of working in that organisation.”

The amendment to Rule 8 is unlikely to withstand the scrutiny of law. The Supreme Court and the high courts have repeatedly upheld the principle that “pension is not a bounty, charity or a gratuitous payment but an indefeasible right of every employee”. The government cannot take away the right merely by giving a show cause notice to a retired official for having used “domain knowledge or expertise” while writing an article/book or speaking at any forum. Any application of this amendment will be thrown out by the courts. No wonder that there has been no known application of the amended rule since 2008. There has been no alarming increase in cases under the Official Secrets Act. Between 2014 and 2019, 50 cases have been filed in the country and none against a government official. And if a government official is actually guilty of violating national security, then is withdrawal of pension an adequate punishment?

What does the government then gain by this amendment? Simple, the new amendment acts as deterrent against criticism by retired officials. Which self-respecting retired government official would like to seek permission from her/his former junior or fight a prolonged legal battle to get his pension restored? The government’s will, thus, prevail not by the wisdom of its decision but by default.

Loss to the nation

All major democracies make optimum use of the experience of their retired government officials. While some become part of the government, others contribute by educating the public and throwing up new ideas/suggestions for the consideration of the government. The domain expert keeps a check on a majoritarian government facing a weak opposition by publicly speaking and writing. All governments try to hide failures and scrutiny for inefficiency. With a weak opposition and government-friendly media, the Bharatiya Janata Party dispensation is more worried about the perceived threat from the retired officials with domain expertise than an ill-informed opposition.

Given the Modi government’s obsession with respect to national security and its lackadaisical performance in its management, it is my view that in the near future, the government will incorporate similar provision in the pension rules of other government departments and the armed forces.

A case in point is the attempt by the Modi government to deny/obfuscate the intelligence failure and the preemptive Chinese intrusions. To date no formal briefing has been given about the actual situation in Eastern Ladakh. Doctored information has been fed to the media through leaks by government/military officials. Three retired defence officers, including the author, brought the real picture before the public through articles and media interviews. All were careful to safeguard operational security. A concerted campaign was launched to discredit these retired officers through government-friendly media and pliant defence analysts until the events overtook their detractors to prove them right. The author extensively used his knowledge of the terrain in Eastern Ladakh to bring the truth before the public. In a similar situation in future, these officers may well be battling in courts to safeguard their pensions.

Imagine a situation that in future when no historical accounts of our wars, counter insurgency/terrorism campaigns and communal riots can be written by retired government and armed forces officers. No retired official will be eligible to head our security related thinks tanks or speak in international forums about our experience. Despite provision of Section 8(3) of the RTI Act to declassify documents after 20 years, the government never does so except to score political points as in the case of Netaji Files.

The amendment to Rule 8 of Central Civil Services (Pension) Rules 1972 is nothing more than a blatant, overarching and draconian gag order against retired officials to manage the public narrative for political interests under the garb of safeguarding national security.

It safeguards the interests of the political dispensation and not the nation. It must be challenged in the courts and in the interim disregarded with contempt.

Friday, 19 April 2019

Who owns the country? The secretive companies hoarding England's land

Multi-million pound corporations with complex structures have purchased the very ground we walk on – and we are only just beginning to discover the damage it is doing to Britain. By Guy Shrubsole in The Guardian

Despite owning 15,000 hectares (37,000 acres) of land, managing a property portfolio worth £2.3bn and having control over huge swaths of central Manchester and Liverpool, very few people have heard of a company named Peel Holdings. It owns the Manchester Ship Canal. It built the Trafford Centre shopping complex and, more recently, sold it in the largest single property acquisition in Britain’s history. It was the developer behind the MediaCityUK site in Salford, to which the BBC and ITV have relocated many of their operations in recent years. Airports, fracking, retail – the list of Peel business interests stretches on and on.

Peel Holdings operates behind the scenes, quietly acquiring land and real estate, cutting billion-pound deals and influencing numerous planning decisions. Its investment decisions have had an enormous impact, whether for good or ill, on the places where millions of people live and work.

Peel’s ultimate owner, the billionaire John Whittaker, is notoriously publicity-shy: he lives on the Isle of Man, has never given an interview and helicopters into his company’s offices for board meetings. He built Peel Holdings in the 1970s and 80s by buying up a series of companies whose fortunes had decayed, but which still controlled valuable land. Foremost among these was the Manchester Ship Canal Company, purchased in 1987. The canal turned out to be valuable not simply as a freight route, but also because of the redevelopment potential of the land that flanked it.

Half of England is owned by less than 1% of the population

Peel Holdings tends not to show its hand in public. Like many companies, it prefers its forays into public political debate to be conducted via intermediary bodies and corporate coalitions. In 2008, it emerged that Peel was a dominant force behind a business grouping that had formed to lobby against Manchester’s proposed congestion charge. The charge was aimed at cutting traffic and reducing the toxic car fumes choking the city. But Peel, as owners of the out-of-town Trafford Centre shopping mall, feared that a congestion charge would be bad for business, discouraging shoppers from driving through central Manchester to reach the mall. Peel’s lobbying paid off: voters rejected the charge in the local referendum and the proposal was dropped.

Throughout England, cash-strapped councils are being outgunned by corporate developers pressing to get their way. The situation is exacerbated by a system that has allowed companies like Peel to keep their corporate structures obscure and their landholdings hidden. A 2013 report by Liverpool-based thinktank Ex Urbe found “well in excess of 300 separately registered UK companies owned or controlled” by Peel. Tracing the conglomerate’s structure is an investigator’s nightmare. Try it yourself on the Companies House website: type in “Peel Land and Property Investments PLC”, and then click through to persons with significant control. This gives you the name of its parent company, Peel Investments Holdings Ltd. So far, so good. But then repeat the steps for the parent company, and yet another holding company emerges; then another, and another. It’s like a series of Russian dolls, one nested inside another.

Until recently, it was even harder to get a handle on the land Peel Holdings owns. Sometimes the company has provided a tantalising glimpse: one map it produced in 2015, as part of some marketing spiel around the “northern powerhouse”, showcases 150 sites it owns across the north-west. It confirms the vast spread of Peel’s landed interests – from Liverpool John Lennon airport, through shale gas well pads, to one of the UK’s largest onshore wind farms. But it’s clearly not everything. A more exhaustive, independent list of the company’s landholdings might allow communities to be forewarned of future developments. As Ex Urbe’s report on Peel concludes: “Peel schemes rarely come to light until they are effectively a fait accompli and the conglomerate is confident they will go ahead, irrespective of public opinion.”

While Peel Holdings is unusual for the sheer amount of land it controls, it is also illustrative of corporate landowners everywhere. Corporations looking to develop land have numerous tricks up their sleeve that they can use to evade scrutiny and get their way, from shell company structures to offshore entities. Companies with big enough budgets can often ride roughshod over the planning system, beating cash-strapped councils and volunteer community groups. And companies have for a long time benefited from having their landholdings kept secret, giving them the element of surprise when it comes to lobbying councils over planning decisions and the use of public space. But now, at long last, that is starting to change. If we want to “take back control” of our country, we need to understand how much of it is currently controlled by corporations.

In 2015, the Private Eye journalist Christian Eriksson lodged a freedom of information (FOI) request with the Land Registry, the official record of land ownership in England and Wales. He asked it to release a database detailing the area of land owned by all UK-registered companies and corporate bodies. Eriksson later shared this database with me, and what it revealed was astonishing. Here, laid bare after the dataset had been cleaned up, was a picture of corporate control: companies today own about 2.6m hectares of land, or roughly 18% of England and Wales.

In the unpromising format of an Excel spreadsheet, a compelling picture emerged. Alongside the utilities privatised by Margaret Thatcher and John Major – the water companies, in particular – and the big corporate landowners, were PLCs with multiple shareholders. There were household names, such as Tesco, Tata Steel and the housebuilder Taylor Wimpey, and others more obscure. MRH Minerals, for example, appeared to own 28,000 hectares of land, making it one of the biggest corporate landowners in England and Wales.

Gradually, I pieced together a list of what looked to be the top 50 landowning companies, which together own more than 405,000 hectares of England and Wales. Peel Holdings and many of its subsidiaries, unsurprisingly, feature high on the list. But while the dataset revealed in stark detail the area of land owned by UK-based companies, it did nothing to tell us what they owned, and where.

That would take another two years to emerge. Meanwhile, Eriksson had been busy at work with his Private Eye colleague Richard Brooks and the computer programmer Anna Powell-Smith, delving into another form of corporate landowner – firms based overseas, yet owning land in the UK. Of particular interest were companies based in offshore tax havens, a wholly legal but controversial practice, given the opportunities offshore ownership gives for possible tax avoidance and for concealing the identities of who ultimately controls a company. Further FOI requests to the Land Registry by Eriksson hit the jackpot when he was sent – “accidentally”, the Land Registry would later claim – a huge dataset of overseas and offshore-registered companies that had bought land in England and Wales between 2005 and 2014: some 113,119 hectares of land and property, worth a staggering £170bn.

Despite owning 15,000 hectares (37,000 acres) of land, managing a property portfolio worth £2.3bn and having control over huge swaths of central Manchester and Liverpool, very few people have heard of a company named Peel Holdings. It owns the Manchester Ship Canal. It built the Trafford Centre shopping complex and, more recently, sold it in the largest single property acquisition in Britain’s history. It was the developer behind the MediaCityUK site in Salford, to which the BBC and ITV have relocated many of their operations in recent years. Airports, fracking, retail – the list of Peel business interests stretches on and on.

Peel Holdings operates behind the scenes, quietly acquiring land and real estate, cutting billion-pound deals and influencing numerous planning decisions. Its investment decisions have had an enormous impact, whether for good or ill, on the places where millions of people live and work.

Peel’s ultimate owner, the billionaire John Whittaker, is notoriously publicity-shy: he lives on the Isle of Man, has never given an interview and helicopters into his company’s offices for board meetings. He built Peel Holdings in the 1970s and 80s by buying up a series of companies whose fortunes had decayed, but which still controlled valuable land. Foremost among these was the Manchester Ship Canal Company, purchased in 1987. The canal turned out to be valuable not simply as a freight route, but also because of the redevelopment potential of the land that flanked it.

Half of England is owned by less than 1% of the population

Peel Holdings tends not to show its hand in public. Like many companies, it prefers its forays into public political debate to be conducted via intermediary bodies and corporate coalitions. In 2008, it emerged that Peel was a dominant force behind a business grouping that had formed to lobby against Manchester’s proposed congestion charge. The charge was aimed at cutting traffic and reducing the toxic car fumes choking the city. But Peel, as owners of the out-of-town Trafford Centre shopping mall, feared that a congestion charge would be bad for business, discouraging shoppers from driving through central Manchester to reach the mall. Peel’s lobbying paid off: voters rejected the charge in the local referendum and the proposal was dropped.

Throughout England, cash-strapped councils are being outgunned by corporate developers pressing to get their way. The situation is exacerbated by a system that has allowed companies like Peel to keep their corporate structures obscure and their landholdings hidden. A 2013 report by Liverpool-based thinktank Ex Urbe found “well in excess of 300 separately registered UK companies owned or controlled” by Peel. Tracing the conglomerate’s structure is an investigator’s nightmare. Try it yourself on the Companies House website: type in “Peel Land and Property Investments PLC”, and then click through to persons with significant control. This gives you the name of its parent company, Peel Investments Holdings Ltd. So far, so good. But then repeat the steps for the parent company, and yet another holding company emerges; then another, and another. It’s like a series of Russian dolls, one nested inside another.

Until recently, it was even harder to get a handle on the land Peel Holdings owns. Sometimes the company has provided a tantalising glimpse: one map it produced in 2015, as part of some marketing spiel around the “northern powerhouse”, showcases 150 sites it owns across the north-west. It confirms the vast spread of Peel’s landed interests – from Liverpool John Lennon airport, through shale gas well pads, to one of the UK’s largest onshore wind farms. But it’s clearly not everything. A more exhaustive, independent list of the company’s landholdings might allow communities to be forewarned of future developments. As Ex Urbe’s report on Peel concludes: “Peel schemes rarely come to light until they are effectively a fait accompli and the conglomerate is confident they will go ahead, irrespective of public opinion.”

While Peel Holdings is unusual for the sheer amount of land it controls, it is also illustrative of corporate landowners everywhere. Corporations looking to develop land have numerous tricks up their sleeve that they can use to evade scrutiny and get their way, from shell company structures to offshore entities. Companies with big enough budgets can often ride roughshod over the planning system, beating cash-strapped councils and volunteer community groups. And companies have for a long time benefited from having their landholdings kept secret, giving them the element of surprise when it comes to lobbying councils over planning decisions and the use of public space. But now, at long last, that is starting to change. If we want to “take back control” of our country, we need to understand how much of it is currently controlled by corporations.

In 2015, the Private Eye journalist Christian Eriksson lodged a freedom of information (FOI) request with the Land Registry, the official record of land ownership in England and Wales. He asked it to release a database detailing the area of land owned by all UK-registered companies and corporate bodies. Eriksson later shared this database with me, and what it revealed was astonishing. Here, laid bare after the dataset had been cleaned up, was a picture of corporate control: companies today own about 2.6m hectares of land, or roughly 18% of England and Wales.

In the unpromising format of an Excel spreadsheet, a compelling picture emerged. Alongside the utilities privatised by Margaret Thatcher and John Major – the water companies, in particular – and the big corporate landowners, were PLCs with multiple shareholders. There were household names, such as Tesco, Tata Steel and the housebuilder Taylor Wimpey, and others more obscure. MRH Minerals, for example, appeared to own 28,000 hectares of land, making it one of the biggest corporate landowners in England and Wales.

Gradually, I pieced together a list of what looked to be the top 50 landowning companies, which together own more than 405,000 hectares of England and Wales. Peel Holdings and many of its subsidiaries, unsurprisingly, feature high on the list. But while the dataset revealed in stark detail the area of land owned by UK-based companies, it did nothing to tell us what they owned, and where.

That would take another two years to emerge. Meanwhile, Eriksson had been busy at work with his Private Eye colleague Richard Brooks and the computer programmer Anna Powell-Smith, delving into another form of corporate landowner – firms based overseas, yet owning land in the UK. Of particular interest were companies based in offshore tax havens, a wholly legal but controversial practice, given the opportunities offshore ownership gives for possible tax avoidance and for concealing the identities of who ultimately controls a company. Further FOI requests to the Land Registry by Eriksson hit the jackpot when he was sent – “accidentally”, the Land Registry would later claim – a huge dataset of overseas and offshore-registered companies that had bought land in England and Wales between 2005 and 2014: some 113,119 hectares of land and property, worth a staggering £170bn.

Victoria Harbour building at Salford Quays, owned by Peel Holdings. Photograph: Mike Robinson/Alamy

Private Eye’s work revealed that a large chunk of the country was not only under corporate control, but owned by companies that – in many cases – were almost certainly seeking to avoid paying tax, that most basic contribution to a civilised society. Some potentially had an even darker motive: purchasing property in England or Wales as a means for kleptocratic regimes or corrupt businessmen to launder money, and to get a healthy return on their ill-gotten gains in the process. This was information that clearly ought to be out in the open, with a huge public interest case for doing so. And yet the government had sat on it for years.

The political ramifications of these revelations were profound. They kickstarted a process of opening up information on land ownership that, although far slower and less complete than many would have liked, has nevertheless transformed our understanding of what companies own. In November 2017, the Land Registry released its corporate and commercial dataset, free of charge and open to all. It revealed, for the first time, the 3.5m land titles owned by UK-based corporate bodies – covering both public sector institutions and private firms – with limited companies owning the majority, 2.1m, of these. But there were two important caveats. Although we now had the addresses owned by companies, the dataset omitted to tell us the size of land they owned. Second, the data lacked accurate information on locations, making it hard to map.

Despite this, what can we now say about company-owned land in England and Wales? Quite a lot, it turns out. We know, for example, that the company with the third-highest number of land titles is the mysterious Wallace Estates, a firm with a £200m property portfolio but virtually no public presence, and which is owned ultimately by a secretive Italian count. Wallace Estates makes its money from the controversial ground rents market, whereby it owns thousands of freehold properties and sells on long leases with annual ground rents.

We also now know that Peel Holdings and its numerous subsidiaries owns at least 1,000 parcels of land across England – not just shopping centres and ports in the north-west, but also a hill in Suffolk, farmland along the Medway and an industrial estate in the Cotswolds. Councils, MPs and residents wanting to keep an eye on what developers and property companies are up to in their area now have a powerful new tool at their disposal.

The data is full of odd quirks and details. Who would have guessed, for instance, that the arms manufacturer BAE owns a nightclub in Cardiff, a pub on Blackpool’s promenade and a service station in Pease Pottage, Sussex? It turns out that they are all investments made by BAE’s pension fund; if selling missiles to Saudi Arabia doesn’t prove profitable enough, it appears the company’s strategy is to make a few quid out of tired drivers stopping for a coffee break off the M23.

The data also lets us peer into the property acquisitions of the big supermarkets, which back in the 1990s and early 2000s involved building up huge land banks to construct ever more out-of-town retail parks. Tesco, via a welter of subsidiaries, owns more than 4,500 hectares of land – and although much of this comprises existing stores, a good chunk also appears to be empty plots, apparently earmarked for future development. One analysis by the Guardian in 2014 estimated that the supermarket was hoarding enough land to accommodate 15,000 homes. More recently, however, Tesco’s financial travails have prompted it to sell off some of its sites. Internet shopping and pricier petrol have made giant hypermarkets built miles from where people live look less and less like smart investments. In 2016, Tesco’s beleaguered CEO announced the company was looking to make better use of the land it owned by selling it for housing, and even by building flats on top of its superstores. As for the supermarkets’ internet shopping rival Amazon, whose gigantic “fulfilment centres” resemble the vast US government warehouse at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark – well, Amazon currently has 16 of those across the UK. And it has grown very quickly: all but one of its property leases have been bought in the past decade.

Companies are increasingly taking over previously public space in cities, too. Recent years have seen a proliferation of Pops – privately owned public spaces – as London, Manchester and other places redevelop and gentrify. You know the sort of thing: expensively landscaped swaths of “public realm”. Aesthetically, they are all very nice, but try to use Pops for some peaceful protest, and you are in for trouble. They are invariably governed by special bylaws and policed by private security, itching to get in your face. I once found this to my cost when staging a tiny, two-person anti-fracking demo outside shale-gas financiers Barclays bank in Canary Wharf. Canary Wharf is partly owned by the Qatari Investment Authority, and – bizarrely – photography is banned. Within a minute of us taking the first selfie on our innocuous protest, security guards had descended en masse, and we spent the next hour running around Canary Wharf trying to evade them.

The Land Registry’s corporate ownership dataset contains millions of entries, and much remains to be uncovered. Some of the information appears trivial at first glance – a company owns a factory here, an office there: so what? But as more people pore over the data, more stories will likely emerge. Future researchers might find intriguing correlations between the locations of England’s thousands of fast-food stores and the health of nearby populations, be able to track gentrification through the displacement of KFC outlets by Nando’s restaurants, and so on.

But to really get under the skin of how companies treat the land they own, and the wider repercussions, we need to zoom in on the housing sector, where debates about companies involved in land banking and profiteering from land sales are crucial to our understanding of the housing crisis.

One particularly controversial aspect of the housing debate that has generated much heat, and little light, in recent years is the debacle over land banking, the practice of hoarding land and holding it back from development until its price increases.

In 2016, the then housing secretary, Sajid Javid, furiously accused large housing developers of land banking and demanded they “release their stranglehold” on land supply. Housebuilders, not used to such impertinence from a Conservative minister, hit back. “As has been proved by various investigations in the past, housebuilders do not land bank,” a spokesperson for the Home Builders Federation told the Telegraph. “In the current market where demand is high, there is absolutely no reason to do so.”

So who is right? This is a complex area, but one that is important to investigate. Can the Land Registry’s corporate ownership data help us get to the bottom of it?

It is common for UK pension funds and insurance companies to buy up land as a long-term strategic investment. Legal & General, for example, owns 1,500 hectares of land that it openly calls a “strategic land portfolio … stretching from Luton to Cardiff”. Its rationale for buying land is simple: “Strategic land holdings are underpinned by their existing use value [such as farming] and give us the opportunity to create further value through planning promotion and infrastructure works over the medium to long term.”

When I looked into where Legal & General’s land was located, I noticed something odd. Nearly all of it lay within green belt areas, where development is restricted. The company appears to have bought it with the aim of lobbying councils to ultimately rip up such restrictions and redesignate the site for development in future.

In the case of pension funds lobbying to rip up the green belt, it’s the planning system that is (rightly) constraining development, not land banking itself. And none of this implicates the usual bogeymen of the housing crisis, the big housebuilding companies. By examining what these major developers own, is it possible to say whether they’re actively engaged in land banking?

There is no doubt that many of the major housebuilding companies own a lot of land. What’s more, housing developers themselves talk about their “current land banks” and publish figures in annual reports listing the number of homes they think they can build using land where they have planning permission. As the housing charity Shelter has found, the top 10 housing developers have land banks with space for more than 400,000 homes – about six years’ supply at current building rates.

Prompted by such statistics, the government ordered a review into build-out rates in 2017, led by Sir Oliver Letwin. Yet when Letwin delivered his draft report, he once again exonerated housebuilders from the charge of land banking. “I cannot find any evidence that the major housebuilders are financial investors of this kind,” he stated, pointing the finger of blame instead at the rate at which new homes could be absorbed into the marketplace.

Part of the problem is that the data on what companies own still isn’t good enough to prove whether or not land banking is occurring. The aforementioned Anna Powell-Smith has tried to map the land owned by housing developers, but has been thwarted by the lack in the Land Registry’s corporate dataset of the necessary information to link data on who owns a site with digital maps of that area. That makes it very hard to assess, for example, whether a piece of land owned by a housebuilder for decades is a prime site accruing in value or a leftover fragment of ground from a past development.

Private Eye’s work revealed that a large chunk of the country was not only under corporate control, but owned by companies that – in many cases – were almost certainly seeking to avoid paying tax, that most basic contribution to a civilised society. Some potentially had an even darker motive: purchasing property in England or Wales as a means for kleptocratic regimes or corrupt businessmen to launder money, and to get a healthy return on their ill-gotten gains in the process. This was information that clearly ought to be out in the open, with a huge public interest case for doing so. And yet the government had sat on it for years.

The political ramifications of these revelations were profound. They kickstarted a process of opening up information on land ownership that, although far slower and less complete than many would have liked, has nevertheless transformed our understanding of what companies own. In November 2017, the Land Registry released its corporate and commercial dataset, free of charge and open to all. It revealed, for the first time, the 3.5m land titles owned by UK-based corporate bodies – covering both public sector institutions and private firms – with limited companies owning the majority, 2.1m, of these. But there were two important caveats. Although we now had the addresses owned by companies, the dataset omitted to tell us the size of land they owned. Second, the data lacked accurate information on locations, making it hard to map.

Despite this, what can we now say about company-owned land in England and Wales? Quite a lot, it turns out. We know, for example, that the company with the third-highest number of land titles is the mysterious Wallace Estates, a firm with a £200m property portfolio but virtually no public presence, and which is owned ultimately by a secretive Italian count. Wallace Estates makes its money from the controversial ground rents market, whereby it owns thousands of freehold properties and sells on long leases with annual ground rents.

We also now know that Peel Holdings and its numerous subsidiaries owns at least 1,000 parcels of land across England – not just shopping centres and ports in the north-west, but also a hill in Suffolk, farmland along the Medway and an industrial estate in the Cotswolds. Councils, MPs and residents wanting to keep an eye on what developers and property companies are up to in their area now have a powerful new tool at their disposal.

The data is full of odd quirks and details. Who would have guessed, for instance, that the arms manufacturer BAE owns a nightclub in Cardiff, a pub on Blackpool’s promenade and a service station in Pease Pottage, Sussex? It turns out that they are all investments made by BAE’s pension fund; if selling missiles to Saudi Arabia doesn’t prove profitable enough, it appears the company’s strategy is to make a few quid out of tired drivers stopping for a coffee break off the M23.

The data also lets us peer into the property acquisitions of the big supermarkets, which back in the 1990s and early 2000s involved building up huge land banks to construct ever more out-of-town retail parks. Tesco, via a welter of subsidiaries, owns more than 4,500 hectares of land – and although much of this comprises existing stores, a good chunk also appears to be empty plots, apparently earmarked for future development. One analysis by the Guardian in 2014 estimated that the supermarket was hoarding enough land to accommodate 15,000 homes. More recently, however, Tesco’s financial travails have prompted it to sell off some of its sites. Internet shopping and pricier petrol have made giant hypermarkets built miles from where people live look less and less like smart investments. In 2016, Tesco’s beleaguered CEO announced the company was looking to make better use of the land it owned by selling it for housing, and even by building flats on top of its superstores. As for the supermarkets’ internet shopping rival Amazon, whose gigantic “fulfilment centres” resemble the vast US government warehouse at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark – well, Amazon currently has 16 of those across the UK. And it has grown very quickly: all but one of its property leases have been bought in the past decade.

Companies are increasingly taking over previously public space in cities, too. Recent years have seen a proliferation of Pops – privately owned public spaces – as London, Manchester and other places redevelop and gentrify. You know the sort of thing: expensively landscaped swaths of “public realm”. Aesthetically, they are all very nice, but try to use Pops for some peaceful protest, and you are in for trouble. They are invariably governed by special bylaws and policed by private security, itching to get in your face. I once found this to my cost when staging a tiny, two-person anti-fracking demo outside shale-gas financiers Barclays bank in Canary Wharf. Canary Wharf is partly owned by the Qatari Investment Authority, and – bizarrely – photography is banned. Within a minute of us taking the first selfie on our innocuous protest, security guards had descended en masse, and we spent the next hour running around Canary Wharf trying to evade them.

The Land Registry’s corporate ownership dataset contains millions of entries, and much remains to be uncovered. Some of the information appears trivial at first glance – a company owns a factory here, an office there: so what? But as more people pore over the data, more stories will likely emerge. Future researchers might find intriguing correlations between the locations of England’s thousands of fast-food stores and the health of nearby populations, be able to track gentrification through the displacement of KFC outlets by Nando’s restaurants, and so on.

But to really get under the skin of how companies treat the land they own, and the wider repercussions, we need to zoom in on the housing sector, where debates about companies involved in land banking and profiteering from land sales are crucial to our understanding of the housing crisis.

One particularly controversial aspect of the housing debate that has generated much heat, and little light, in recent years is the debacle over land banking, the practice of hoarding land and holding it back from development until its price increases.

In 2016, the then housing secretary, Sajid Javid, furiously accused large housing developers of land banking and demanded they “release their stranglehold” on land supply. Housebuilders, not used to such impertinence from a Conservative minister, hit back. “As has been proved by various investigations in the past, housebuilders do not land bank,” a spokesperson for the Home Builders Federation told the Telegraph. “In the current market where demand is high, there is absolutely no reason to do so.”

So who is right? This is a complex area, but one that is important to investigate. Can the Land Registry’s corporate ownership data help us get to the bottom of it?

It is common for UK pension funds and insurance companies to buy up land as a long-term strategic investment. Legal & General, for example, owns 1,500 hectares of land that it openly calls a “strategic land portfolio … stretching from Luton to Cardiff”. Its rationale for buying land is simple: “Strategic land holdings are underpinned by their existing use value [such as farming] and give us the opportunity to create further value through planning promotion and infrastructure works over the medium to long term.”

When I looked into where Legal & General’s land was located, I noticed something odd. Nearly all of it lay within green belt areas, where development is restricted. The company appears to have bought it with the aim of lobbying councils to ultimately rip up such restrictions and redesignate the site for development in future.

In the case of pension funds lobbying to rip up the green belt, it’s the planning system that is (rightly) constraining development, not land banking itself. And none of this implicates the usual bogeymen of the housing crisis, the big housebuilding companies. By examining what these major developers own, is it possible to say whether they’re actively engaged in land banking?

There is no doubt that many of the major housebuilding companies own a lot of land. What’s more, housing developers themselves talk about their “current land banks” and publish figures in annual reports listing the number of homes they think they can build using land where they have planning permission. As the housing charity Shelter has found, the top 10 housing developers have land banks with space for more than 400,000 homes – about six years’ supply at current building rates.

Prompted by such statistics, the government ordered a review into build-out rates in 2017, led by Sir Oliver Letwin. Yet when Letwin delivered his draft report, he once again exonerated housebuilders from the charge of land banking. “I cannot find any evidence that the major housebuilders are financial investors of this kind,” he stated, pointing the finger of blame instead at the rate at which new homes could be absorbed into the marketplace.

Part of the problem is that the data on what companies own still isn’t good enough to prove whether or not land banking is occurring. The aforementioned Anna Powell-Smith has tried to map the land owned by housing developers, but has been thwarted by the lack in the Land Registry’s corporate dataset of the necessary information to link data on who owns a site with digital maps of that area. That makes it very hard to assess, for example, whether a piece of land owned by a housebuilder for decades is a prime site accruing in value or a leftover fragment of ground from a past development.

Shoppers in the Trafford Centre, a shopping mall until recently owned by Peel Holdings. Photograph: Oli Scarff/AFP/Getty

Second, the scope of Letwin’s review was drawn too narrowly to examine the wider problem of land banking by landowners beyond the major housebuilders. As the housing market analyst Neal Hudson said when it was published, the “review remit ignored the most important and unknown bit of the market: sites and land ownership pre-planning.”

In fact, if Letwin had raised his sights a little higher, he would have seen there is a whole industry of land promoters working with landowners to promote sites, have them earmarked for development in the council’s local plan, and increase their asking price. As investigations by Isabelle Fraser of the Telegraph have revealed: “A group of private companies, largely unknown to the public, have carved out a lucrative niche locating and snapping up land across the UK.”

One such company, Gladman Land, boasts on its website of a 90% success rate at getting sites developed. Few of these firms appear to own much land themselves; rather, they work with other landowners, perhaps signing options agreements or other such deals. Consultants Molior have estimated that between 25% and 45% of sites with planning permission in London are owned by companies that have never built a home.

This gets us to the heart of the housing crisis. Sure, we need housing developers to build more homes. But most of all we need them to build affordable homes. And developers that are forced to pay through the nose to persuade landowners to part with their land end up with less money left over for good-quality, affordable housing. By all means, let’s continue to pressure housebuilders whenever they try to renege on their planning agreements. But at root, we have to find ways to encourage landowners of all kinds – corporate or otherwise – to part with their land at cheaper prices.

Since the first appearance of modern corporations in the Victorian period, companies have expanded to become the owners of nearly a fifth of all land in England and Wales. Much of this land acquisition is uncontested: space for a factory here, an office block there. But some of it has proven highly controversial. Huge retailers and property groups like Tesco and Peel Holdings have eroded town centres and high streets by amassing land for out-of-town superstores, and lobbied to maintain a culture of car dependency. Multinational agribusinesses have exacerbated the industrialisation of our food supply and accelerated the decline of small-scale farmers. Property firms have made tidy profits from the privatisation of formerly public land – which might otherwise have gone into the public purse, had previous governments treated their assets more wisely.

Though the veil of secrecy around company structures and what corporations own is at last lifting, thanks to recent data disclosures by government, there’s still much that needs to be done to make sense of this new information. The Land Registry needs to disclose proper maps of what companies own if we are to get to the bottom of suspect practices like land banking, and give communities a fighting chance in local planning battles.

Legally obliged to maximise profits for their shareholders, and biased towards short-term returns, companies make for poor custodians of land. Nor are corporate landowners capable of solving the housing crisis. Hoarded, developed, polluted, dug up, landfilled: the corporate control of England’s acres has gone far enough.

Second, the scope of Letwin’s review was drawn too narrowly to examine the wider problem of land banking by landowners beyond the major housebuilders. As the housing market analyst Neal Hudson said when it was published, the “review remit ignored the most important and unknown bit of the market: sites and land ownership pre-planning.”

In fact, if Letwin had raised his sights a little higher, he would have seen there is a whole industry of land promoters working with landowners to promote sites, have them earmarked for development in the council’s local plan, and increase their asking price. As investigations by Isabelle Fraser of the Telegraph have revealed: “A group of private companies, largely unknown to the public, have carved out a lucrative niche locating and snapping up land across the UK.”

One such company, Gladman Land, boasts on its website of a 90% success rate at getting sites developed. Few of these firms appear to own much land themselves; rather, they work with other landowners, perhaps signing options agreements or other such deals. Consultants Molior have estimated that between 25% and 45% of sites with planning permission in London are owned by companies that have never built a home.

This gets us to the heart of the housing crisis. Sure, we need housing developers to build more homes. But most of all we need them to build affordable homes. And developers that are forced to pay through the nose to persuade landowners to part with their land end up with less money left over for good-quality, affordable housing. By all means, let’s continue to pressure housebuilders whenever they try to renege on their planning agreements. But at root, we have to find ways to encourage landowners of all kinds – corporate or otherwise – to part with their land at cheaper prices.

Since the first appearance of modern corporations in the Victorian period, companies have expanded to become the owners of nearly a fifth of all land in England and Wales. Much of this land acquisition is uncontested: space for a factory here, an office block there. But some of it has proven highly controversial. Huge retailers and property groups like Tesco and Peel Holdings have eroded town centres and high streets by amassing land for out-of-town superstores, and lobbied to maintain a culture of car dependency. Multinational agribusinesses have exacerbated the industrialisation of our food supply and accelerated the decline of small-scale farmers. Property firms have made tidy profits from the privatisation of formerly public land – which might otherwise have gone into the public purse, had previous governments treated their assets more wisely.

Though the veil of secrecy around company structures and what corporations own is at last lifting, thanks to recent data disclosures by government, there’s still much that needs to be done to make sense of this new information. The Land Registry needs to disclose proper maps of what companies own if we are to get to the bottom of suspect practices like land banking, and give communities a fighting chance in local planning battles.

Legally obliged to maximise profits for their shareholders, and biased towards short-term returns, companies make for poor custodians of land. Nor are corporate landowners capable of solving the housing crisis. Hoarded, developed, polluted, dug up, landfilled: the corporate control of England’s acres has gone far enough.

Thursday, 19 January 2017

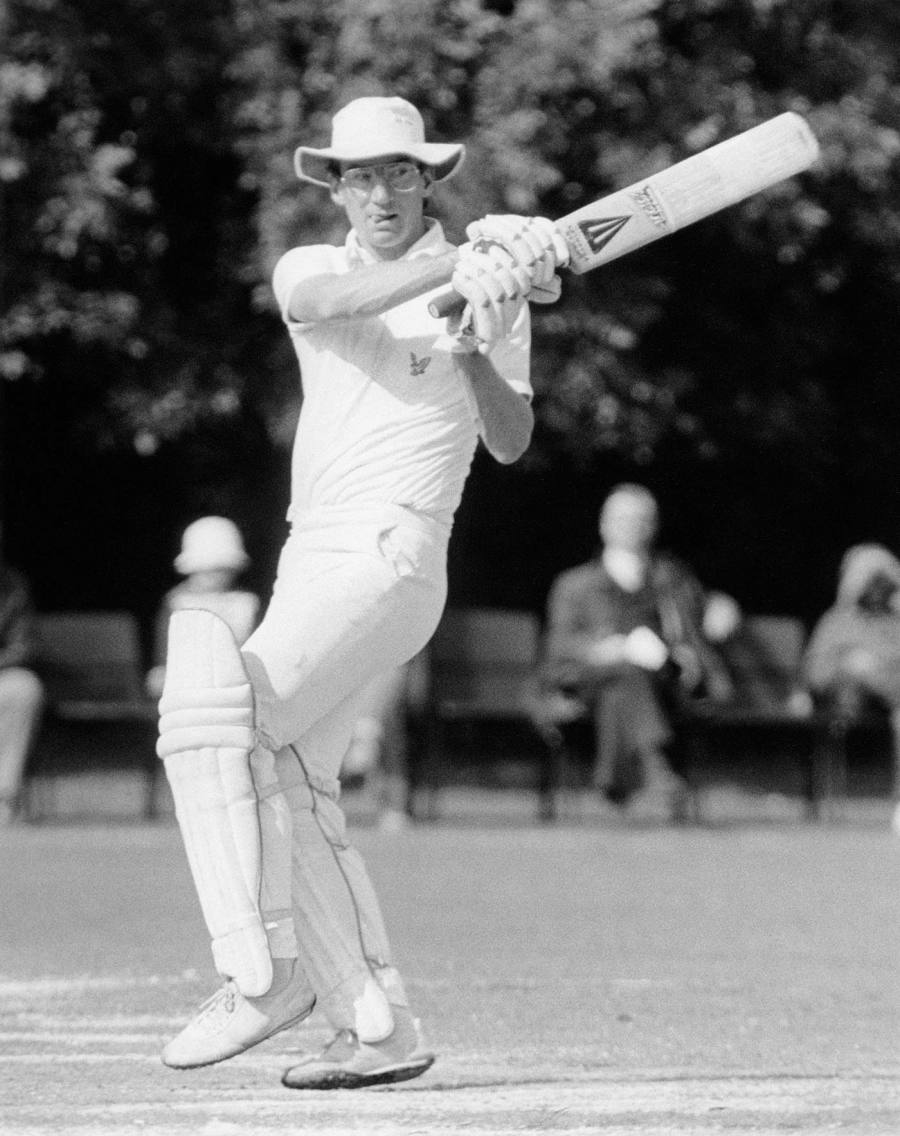

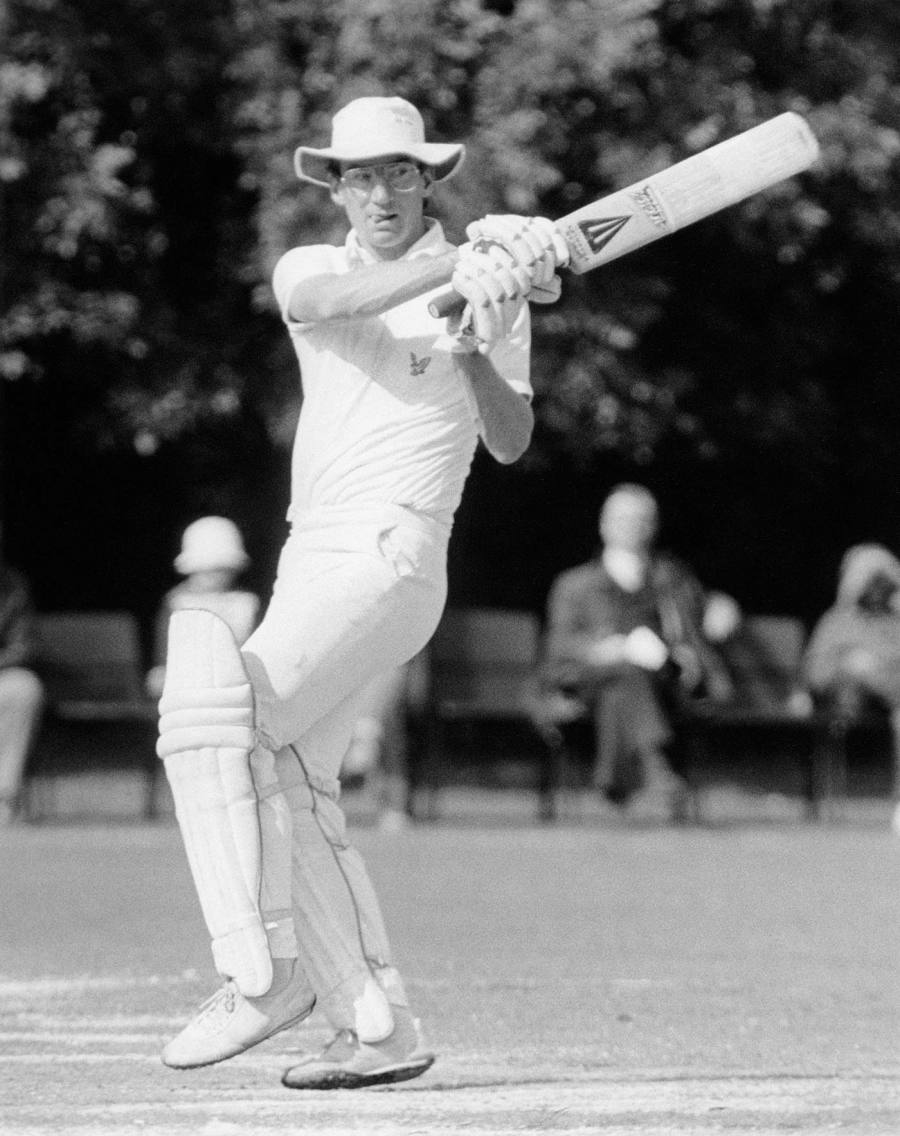

Peter Roebuck's Somerset agony

David Hopps in Cricinfo

The civil war that beset Somerset cricket more than 30 years ago was all the more remarkable because of the unimposing, bespectacled figure at its centre. Peter Roebuck would not have immediately struck a casual observer as a man capable of going to war. An unconventional loner, gauche even with close friends, he did not meld easily with either the old-fashioned administrators in charge of the club or the imposing superstars, Ian Botham, Viv Richards and Joel Garner, who would eventually be expunged from a Somerset dressing room that had fallen on hard times.

The conflict that took hold of the sleepy market town of Taunton throughout the summer of 1986 dominated the sports pages in a way that now is hard to imagine. Until now, it has only been possible to hazard a guess at Roebuck's state of mind as he became the principal hate figure for rebel supporters who were campaigning against the county's decision to release their great, long-serving West Indians, Richards and Garner and, as a consequence, accept the ensuing departure of Ian Botham in protest.

Previously unpublished diaries, which were not made available to the authors of the excellent Chasing Shadows: The Life and Death of Peter Roebuck in 2015, have now revealed the full extent of Roebuck's mental anguish. Condemned by his critics, increasingly reviled by Botham in a rift that would last a lifetime, and often left to flounder by Somerset's archaic administration, he presents himself as an honourable man who made his choice and forever fretted over the consequences.

"Lots of people are asking about my health," he writes as Somerset's warfare reaches its height. "I suspect they are waiting for a crack-up." Somerset comfortably won the vote to let go of Richards and Garner at an emergency meeting at Shepton Mallet in November 1986, and Roebuck took the spoils, but his life would never be the same again. Even as victory approaches, he rails at English society as "mean, narrow and vindictive" and falls out of love with the country of his birth for the rest of a life that was to end in tragic circumstances 25 years later.

By the time he wrote his autobiography, Sometimes I Forgot To Laugh, in 2004, Roebuck was able to tell the Somerset story with relative calm. Not so in his diaries, typed out contemporaneously in obsessive detail, complete with scribbled adjustments. Three unseen chapters of a book called 1986 And All That have been discovered and placed on the family website. "The truth can finally be told," is how the family puts it.

Roebuck was in his first season as Somerset captain, regarding himself as a more relaxed figure, at 30, than the intense batsman who had written the self-absorbed study of life on the county circuit, Slices of Cricket, a few years earlier. That self-ease soon departed. In midsummer he was informed at an emergency meeting of the management and cricket committee that Martin Crowe, not yet a New Zealand star, merely a young batsman making his way, and someone who had spent time with Somerset's 2nd XI with an eye to a future signing, had been approached by Essex.

Crowe, Roebuck writes, was "a man of brilliance rare in the game, a man of standards rare in the game". Roebuck's yearning to reshape a failing, ageing Somerset side has youth and work ethic at its core and encourages him to support the majority preference on the committee to sign Crowe and release Richards and Garner after many years of loyal service. One wonders how Botham will respond to Roebuck's allegation in the diaries that Botham viewed Crowe at the time as little better than a good club player.

In Somerset, Richards and Garner were far more than overseas players. They were part of their limited-overs folklore, as much a part of Somerset as scrumpy or skittles. As Roebuck, this cricketing aesthete, frets over the implications, he writes in his diary: "Echoes in my mind kept repeating that this Somerset team could never work, could never be worthwhile unless we abandoned the past and began to build a team around Crowe. Our chemistry was wrong. It hadn't worked with Botham as captain, and it wasn't working with Roebuck as captain. We'd lose Crowe to Essex."

The civil war that beset Somerset cricket more than 30 years ago was all the more remarkable because of the unimposing, bespectacled figure at its centre. Peter Roebuck would not have immediately struck a casual observer as a man capable of going to war. An unconventional loner, gauche even with close friends, he did not meld easily with either the old-fashioned administrators in charge of the club or the imposing superstars, Ian Botham, Viv Richards and Joel Garner, who would eventually be expunged from a Somerset dressing room that had fallen on hard times.

The conflict that took hold of the sleepy market town of Taunton throughout the summer of 1986 dominated the sports pages in a way that now is hard to imagine. Until now, it has only been possible to hazard a guess at Roebuck's state of mind as he became the principal hate figure for rebel supporters who were campaigning against the county's decision to release their great, long-serving West Indians, Richards and Garner and, as a consequence, accept the ensuing departure of Ian Botham in protest.

Previously unpublished diaries, which were not made available to the authors of the excellent Chasing Shadows: The Life and Death of Peter Roebuck in 2015, have now revealed the full extent of Roebuck's mental anguish. Condemned by his critics, increasingly reviled by Botham in a rift that would last a lifetime, and often left to flounder by Somerset's archaic administration, he presents himself as an honourable man who made his choice and forever fretted over the consequences.

"Lots of people are asking about my health," he writes as Somerset's warfare reaches its height. "I suspect they are waiting for a crack-up." Somerset comfortably won the vote to let go of Richards and Garner at an emergency meeting at Shepton Mallet in November 1986, and Roebuck took the spoils, but his life would never be the same again. Even as victory approaches, he rails at English society as "mean, narrow and vindictive" and falls out of love with the country of his birth for the rest of a life that was to end in tragic circumstances 25 years later.

By the time he wrote his autobiography, Sometimes I Forgot To Laugh, in 2004, Roebuck was able to tell the Somerset story with relative calm. Not so in his diaries, typed out contemporaneously in obsessive detail, complete with scribbled adjustments. Three unseen chapters of a book called 1986 And All That have been discovered and placed on the family website. "The truth can finally be told," is how the family puts it.

Roebuck was in his first season as Somerset captain, regarding himself as a more relaxed figure, at 30, than the intense batsman who had written the self-absorbed study of life on the county circuit, Slices of Cricket, a few years earlier. That self-ease soon departed. In midsummer he was informed at an emergency meeting of the management and cricket committee that Martin Crowe, not yet a New Zealand star, merely a young batsman making his way, and someone who had spent time with Somerset's 2nd XI with an eye to a future signing, had been approached by Essex.

Crowe, Roebuck writes, was "a man of brilliance rare in the game, a man of standards rare in the game". Roebuck's yearning to reshape a failing, ageing Somerset side has youth and work ethic at its core and encourages him to support the majority preference on the committee to sign Crowe and release Richards and Garner after many years of loyal service. One wonders how Botham will respond to Roebuck's allegation in the diaries that Botham viewed Crowe at the time as little better than a good club player.

In Somerset, Richards and Garner were far more than overseas players. They were part of their limited-overs folklore, as much a part of Somerset as scrumpy or skittles. As Roebuck, this cricketing aesthete, frets over the implications, he writes in his diary: "Echoes in my mind kept repeating that this Somerset team could never work, could never be worthwhile unless we abandoned the past and began to build a team around Crowe. Our chemistry was wrong. It hadn't worked with Botham as captain, and it wasn't working with Roebuck as captain. We'd lose Crowe to Essex."

Botham at the press conference announcing his decision to leave Somerset Adrian Murrell / © Getty Images