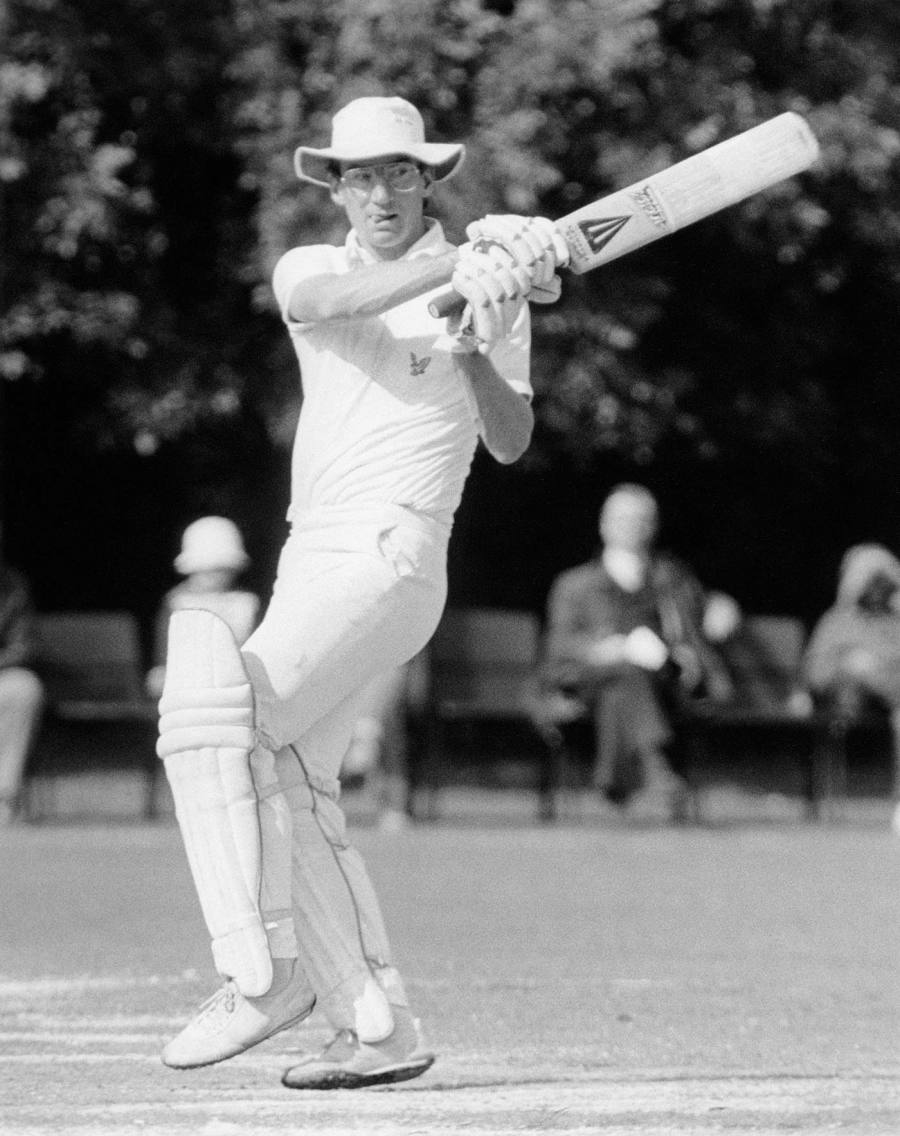

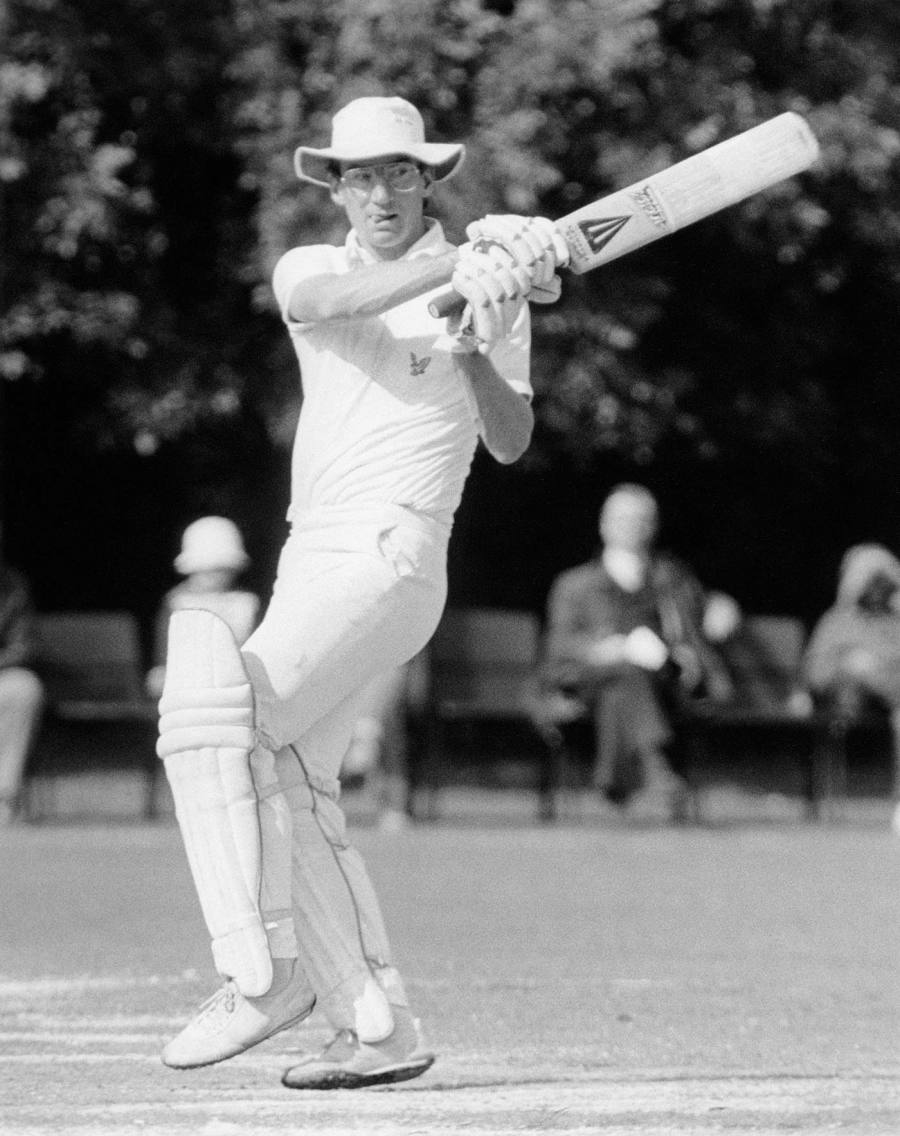

The civil war that beset Somerset cricket more than 30 years ago was all the more remarkable because of the unimposing, bespectacled figure at its centre. Peter Roebuck would not have immediately struck a casual observer as a man capable of going to war. An unconventional loner, gauche even with close friends, he did not meld easily with either the old-fashioned administrators in charge of the club or the imposing superstars, Ian Botham, Viv Richards and Joel Garner, who would eventually be expunged from a Somerset dressing room that had fallen on hard times.

The conflict that took hold of the sleepy market town of Taunton throughout the summer of 1986 dominated the sports pages in a way that now is hard to imagine. Until now, it has only been possible to hazard a guess at Roebuck's state of mind as he became the principal hate figure for rebel supporters who were campaigning against the county's decision to release their great, long-serving West Indians, Richards and Garner and, as a consequence, accept the ensuing departure of Ian Botham in protest.

Previously unpublished diaries, which were not made available to the authors of the excellent Chasing Shadows: The Life and Death of Peter Roebuck in 2015, have now revealed the full extent of Roebuck's mental anguish. Condemned by his critics, increasingly reviled by Botham in a rift that would last a lifetime, and often left to flounder by Somerset's archaic administration, he presents himself as an honourable man who made his choice and forever fretted over the consequences.

"Lots of people are asking about my health," he writes as Somerset's warfare reaches its height. "I suspect they are waiting for a crack-up." Somerset comfortably won the vote to let go of Richards and Garner at an emergency meeting at Shepton Mallet in November 1986, and Roebuck took the spoils, but his life would never be the same again. Even as victory approaches, he rails at English society as "mean, narrow and vindictive" and falls out of love with the country of his birth for the rest of a life that was to end in tragic circumstances 25 years later.

By the time he wrote his autobiography, Sometimes I Forgot To Laugh, in 2004, Roebuck was able to tell the Somerset story with relative calm. Not so in his diaries, typed out contemporaneously in obsessive detail, complete with scribbled adjustments. Three unseen chapters of a book called 1986 And All That have been discovered and placed on the family website. "The truth can finally be told," is how the family puts it.

Roebuck was in his first season as Somerset captain, regarding himself as a more relaxed figure, at 30, than the intense batsman who had written the self-absorbed study of life on the county circuit, Slices of Cricket, a few years earlier. That self-ease soon departed. In midsummer he was informed at an emergency meeting of the management and cricket committee that Martin Crowe, not yet a New Zealand star, merely a young batsman making his way, and someone who had spent time with Somerset's 2nd XI with an eye to a future signing, had been approached by Essex.

Crowe, Roebuck writes, was "a man of brilliance rare in the game, a man of standards rare in the game". Roebuck's yearning to reshape a failing, ageing Somerset side has youth and work ethic at its core and encourages him to support the majority preference on the committee to sign Crowe and release Richards and Garner after many years of loyal service. One wonders how Botham will respond to Roebuck's allegation in the diaries that Botham viewed Crowe at the time as little better than a good club player.

In Somerset, Richards and Garner were far more than overseas players. They were part of their limited-overs folklore, as much a part of Somerset as scrumpy or skittles. As Roebuck, this cricketing aesthete, frets over the implications, he writes in his diary: "Echoes in my mind kept repeating that this Somerset team could never work, could never be worthwhile unless we abandoned the past and began to build a team around Crowe. Our chemistry was wrong. It hadn't worked with Botham as captain, and it wasn't working with Roebuck as captain. We'd lose Crowe to Essex."

Botham at the press conference announcing his decision to leave Somerset Adrian Murrell / © Getty Images

A couple of weeks later, that course of action was confirmed. Sworn to secrecy until the end of the season by a Somerset management and cricket committee of 12, a body which Roebuck naively imagines is capable of confidentiality, he ludicrously seeks to maintain discretion in the height of summer in a dressing room awash with rumour. Out on the field, "smiles hid hatred". In Roebuck's version of events, all those responsible for the decision keep their heads down and often fail to tell him what is going on. Rebels soon force an emergency special meeting, and at the end of the season virtually everybody but him seems to disappear for a prolonged holiday - acts, in some cases, of breathtaking irresponsibility. He delays his return to Australia, where he spends the close season, to see the job through.

"I was bound to be forsaken by friends," he writes. "It was all right for them, they were amateurs, committee men, they could leave this club and this game at any moment. It was my living, much more was at stake."

A cerebral and unclubbable man, he is ill-equipped for the task - whether the art of appeasement or politics. Lost in his own thoughts, he reads cricket books, watches movies, takes long baths, and makes impromptu visits around the county in search of understanding. Some imagined friends desert him, some of them quite cruelly, and, for the first time, he is assailed by scurrilous rumours about his private life. Tabloid journalists descend upon Taunton, enquiring about his relationship with the young cricketers he houses on an annual basis. Fifteen years later, his belief in the educative value of corporal punishment was to lead to a guilty plea, to his instant regret, to three charges of common assault against South African teenagers.

Roebuck's insistence that he will not surrender to "moral blackmail" is one of the most revealing passages in these freshly discovered chapters. "These tactics, this moral blackmail, this offer not to tell lies if I will not tell facts, must not rush me into a hasty marriage with attendant car and nappies. Through my life so far, I've tried to be as independent, financially and personally, as possible… I fear love for its invasion of privacy though now, at last, I begin to think about it. For the present, I have two lives (in England and Australia), three careers (cricket, writing, teaching), and a variety of ways of keeping the world, though not friendship, at its distance. I don't care a jot what anyone else does in private, so long as it does not hurt people. I want to help the young, something I've failed to do so far in my years at Somerset because I was too involved in my own game to care for anyone else."

The Roebuck family website goes as far as to suggest "a causal connection" between events at Somerset that fateful summer and the manner in which his life came to a tragic end many years later. You would have to be a believer in chaos theory to accept this conclusion without reservation.

Another 25 years elapsed before Roebuck fell to his death from a Cape Town hotel window in 2011 while being questioned by police about an alleged sexual assault, which remains unproven. A police statement at the time said that Roebuck, by then a celebrated author and journalist, committed suicide, a version of events that was accepted by a closed inquest, before last month South Africa's Director of Public Prosecutions responded to family lobbying and agreed to review the findings.

In mental turmoil he might have been, but Roebuck required no passage of time to see the mid-1980s as a period when county cricket's unwieldy amateur committees were no longer fit for purpose, unable to deal with the advent of the celebrity cricketer. It is no coincidence that the mid-'80s also saw county cricket's other great conflict, as Yorkshire descended into internecine strife over the future of Geoffrey Boycott.

"Somerset, a small county area with a small county cricket team is one of the battlegrounds upon which this battle is taking place. It is a battle between old-fashioned standards and celebration of stardom. It isn't really a battle between management and worker at all. Botham is not a worker, cannot pretend to be a working class hero. In this battle the management and the workers are on the same side. "

A couple of weeks later, that course of action was confirmed. Sworn to secrecy until the end of the season by a Somerset management and cricket committee of 12, a body which Roebuck naively imagines is capable of confidentiality, he ludicrously seeks to maintain discretion in the height of summer in a dressing room awash with rumour. Out on the field, "smiles hid hatred". In Roebuck's version of events, all those responsible for the decision keep their heads down and often fail to tell him what is going on. Rebels soon force an emergency special meeting, and at the end of the season virtually everybody but him seems to disappear for a prolonged holiday - acts, in some cases, of breathtaking irresponsibility. He delays his return to Australia, where he spends the close season, to see the job through.

"I was bound to be forsaken by friends," he writes. "It was all right for them, they were amateurs, committee men, they could leave this club and this game at any moment. It was my living, much more was at stake."

A cerebral and unclubbable man, he is ill-equipped for the task - whether the art of appeasement or politics. Lost in his own thoughts, he reads cricket books, watches movies, takes long baths, and makes impromptu visits around the county in search of understanding. Some imagined friends desert him, some of them quite cruelly, and, for the first time, he is assailed by scurrilous rumours about his private life. Tabloid journalists descend upon Taunton, enquiring about his relationship with the young cricketers he houses on an annual basis. Fifteen years later, his belief in the educative value of corporal punishment was to lead to a guilty plea, to his instant regret, to three charges of common assault against South African teenagers.

Roebuck's insistence that he will not surrender to "moral blackmail" is one of the most revealing passages in these freshly discovered chapters. "These tactics, this moral blackmail, this offer not to tell lies if I will not tell facts, must not rush me into a hasty marriage with attendant car and nappies. Through my life so far, I've tried to be as independent, financially and personally, as possible… I fear love for its invasion of privacy though now, at last, I begin to think about it. For the present, I have two lives (in England and Australia), three careers (cricket, writing, teaching), and a variety of ways of keeping the world, though not friendship, at its distance. I don't care a jot what anyone else does in private, so long as it does not hurt people. I want to help the young, something I've failed to do so far in my years at Somerset because I was too involved in my own game to care for anyone else."

The Roebuck family website goes as far as to suggest "a causal connection" between events at Somerset that fateful summer and the manner in which his life came to a tragic end many years later. You would have to be a believer in chaos theory to accept this conclusion without reservation.

Another 25 years elapsed before Roebuck fell to his death from a Cape Town hotel window in 2011 while being questioned by police about an alleged sexual assault, which remains unproven. A police statement at the time said that Roebuck, by then a celebrated author and journalist, committed suicide, a version of events that was accepted by a closed inquest, before last month South Africa's Director of Public Prosecutions responded to family lobbying and agreed to review the findings.

In mental turmoil he might have been, but Roebuck required no passage of time to see the mid-1980s as a period when county cricket's unwieldy amateur committees were no longer fit for purpose, unable to deal with the advent of the celebrity cricketer. It is no coincidence that the mid-'80s also saw county cricket's other great conflict, as Yorkshire descended into internecine strife over the future of Geoffrey Boycott.

"Somerset, a small county area with a small county cricket team is one of the battlegrounds upon which this battle is taking place. It is a battle between old-fashioned standards and celebration of stardom. It isn't really a battle between management and worker at all. Botham is not a worker, cannot pretend to be a working class hero. In this battle the management and the workers are on the same side. "

Roebuck bats in a benefit match for Botham in Finchley, London © Getty Images

Somerset's general committee is elderly white males to a man, and when Roebuck goes to an area committee meeting in the seaside town of Weston, where incidentally he finds warm support, he learns that a 26-strong committee has been extended to 27 just because somebody else asked to join. "We must change this old, male hegemony in charge of cricket," he writes. "A game cannot, in 1986, be run by genial, sensible pensioners. It is frightening how much cricket depends on the tireless voluntary work of old men."

Much has been made over the years about the enmity that grew from this summer onwards between Roebuck and Botham, polar opposites in character and cricketing approach, But it is Roebuck's fear of Richards' volcanic temperament that stands out most in these unseen chapters, such as an exchange during a Championship match at Worcester, after Somerset's intentions are known, a day that begins with Roebuck strolling by the banks of the Severn in search of rural bliss and soon becomes something altogether more tempestuous.

"Viv asked to see me in private, so we went upstairs where we wouldn't be disturbed. For the next 15 minutes he launched a tirade of abuse […] He said I was a sick boy, a terrible failure, an unstable character, someone who should never be put in charge of anything… He said I hadn't yet seen his bad side and he'd unleash it upon me from now on. During this torrent, I sat quietly, not angry at all though a little startled."

Tensions with Botham are also laid bare. "Botham is trying to form the players into a gang behind him," Roebuck writes. "He's shown little interest in these young cricketers on previous occasions, but he is a formidable warrior… If he can't win them over he'd certainly try to bully them into line." He even explores likenesses between Botham and Percy Chapman, an Ashes-winning captain in 1926, who "fell into decline, drinking heavily and putting on weight, ravaging his body". He questions Botham's desire to be surrounded by like-minded "chums", not stopping to reflect that he himself was also bent upon building a Somerset side in his own image.

"I am not a loner," he concludes, "rather my preferred pursuits (reading, writing, music) are solitary. I am private, it is true, and enjoy the companionship of my close friends much more than the conviviality of a loud, large group. As for splitting the team, the whole point of this struggle was that it had been split for years."

Somerset's general committee is elderly white males to a man, and when Roebuck goes to an area committee meeting in the seaside town of Weston, where incidentally he finds warm support, he learns that a 26-strong committee has been extended to 27 just because somebody else asked to join. "We must change this old, male hegemony in charge of cricket," he writes. "A game cannot, in 1986, be run by genial, sensible pensioners. It is frightening how much cricket depends on the tireless voluntary work of old men."

Much has been made over the years about the enmity that grew from this summer onwards between Roebuck and Botham, polar opposites in character and cricketing approach, But it is Roebuck's fear of Richards' volcanic temperament that stands out most in these unseen chapters, such as an exchange during a Championship match at Worcester, after Somerset's intentions are known, a day that begins with Roebuck strolling by the banks of the Severn in search of rural bliss and soon becomes something altogether more tempestuous.

"Viv asked to see me in private, so we went upstairs where we wouldn't be disturbed. For the next 15 minutes he launched a tirade of abuse […] He said I was a sick boy, a terrible failure, an unstable character, someone who should never be put in charge of anything… He said I hadn't yet seen his bad side and he'd unleash it upon me from now on. During this torrent, I sat quietly, not angry at all though a little startled."

Tensions with Botham are also laid bare. "Botham is trying to form the players into a gang behind him," Roebuck writes. "He's shown little interest in these young cricketers on previous occasions, but he is a formidable warrior… If he can't win them over he'd certainly try to bully them into line." He even explores likenesses between Botham and Percy Chapman, an Ashes-winning captain in 1926, who "fell into decline, drinking heavily and putting on weight, ravaging his body". He questions Botham's desire to be surrounded by like-minded "chums", not stopping to reflect that he himself was also bent upon building a Somerset side in his own image.

"I am not a loner," he concludes, "rather my preferred pursuits (reading, writing, music) are solitary. I am private, it is true, and enjoy the companionship of my close friends much more than the conviviality of a loud, large group. As for splitting the team, the whole point of this struggle was that it had been split for years."