Just off to a meeting? Stop right now. Turn back. You will be stuck in an overheated room, chained to a table for an absurd length of time and stopped from proper work. Worse, we are now told that just sitting there is a killer. It shortens life. You will die.

According to Public Health England, we are so addicted to meetings that we don’t realise the threat they pose to ourselves and our organisations. Its chief executive, Duncan Selbie, told this week’s annual meeting that sitting in meetings “haemorrhages productivity”. It slows metabolism and affects the body’s capacity to regulate its sugar and thus blood pressure. This leads to obesity, diabetes, cancer … and death. So don’t do it. Don’t go.

The Get Britain Standing campaign agrees. It says that sedentary office activity is now as dangerous to health as smoking. It takes an hour of exercise to eliminate the toxins built up in one round-table session. Meanwhile, the Columbia University Medical Center this week produced a no less alarming statistic. After tracking 8,000 individuals in all walks of life, it concluded that inactivity for 13 hours a day (including sleep) makes “risk of death” 2.6 times more likely than it is for inactivity of less than 11 hours.

The best meeting is spent walking, like in The West Wing. (The fact that all West Wingers seem on the verge of a heart attack is apparently irrelevant.) Mike Loosemore of the Institute of Sport, Exercise and Health rather desperately advises regularly standing up and getting a glass of water. Neanderthals must be laughing themselves sick at what Homo sapiens has to do just to survive.

While we can take that with a pinch of salt, it feeds a wider meetings malaise. All the revolutions of the internet – Skype, Facebook, Twitter – have not diminished humankind’s craving to gather in tedious conclave. Executives ruthless towards workplace productivity are careless of their own offices. Meetings are the cocaine rush of the corporation. I am told there are scores of executives at the BBC, an institution famously addicted to the meetings culture, who are so high on the stuff that they spend the entire day in meetings, and return home with no one any the wiser, except those who pay their salaries.

It is half a century since C Northcote Parkinson first addressed the meeting as social anthropology, yielding his celebrated “coefficient of inefficiency”. It calculated that a meeting of just five people was “most likely to act with competence, secrecy and speed”. Few such bodies exist because five swiftly expands to nine: and two of the nine tend to be “merely ornamental”, people whom no one has the heart to exclude.

Above nine, said Parkinson, “the organism begins to perish”. Once the meeting reaches 20 people, it may as well go on to 100, since by then most of those present are not contributing. They are spectating, talking to each other, squabbling or forming lobbies. Nowadays many are peering at their phones or tablets – pretending to take notes, or frantic not to fall asleep. All are praying for “any other business”.

Management research on meetings is uniformly hostile, yet like most research it has not the slightest practical effect. A recent study by Microsoft, America Online and Salary.com found that the average person works only three days a week. The rest of working time was regarded as wasted, with “unproductive meetings” heading the list. Workers on average regard a third of any meeting as pointless.

Minnesota University’s “decisions” guru, the psychologist Kathleen Vohs, has shown that most executives have a limited stock of “cognitive resource”. It depletes over time, like physical energy. People get impatient, they tire and take worse decisions. Curiously, they leave feeling exhausted, despite hours spent doing nothing at all. Four-hour board or “strategy” meetings are probably disastrous to the firm, inducing torpor, claustrophobia and misjudgment.

Yet still recruits arrive from management schools and consultancies, brilliant zombies doped to the eyeballs in presentations “delivering strategic solutions going forward by thinking out of the box”. They are like chateau generals, kept well away from the front line, versed in the parlour games of the articulate classes. They are for coffee and biscuits, not the watercooler.

Nothing is likely to cut this flab. The meeting has become the ceremony of executive importance: who calls it, who chairs it, who presents to it, who is invited and who is not. Its status is a classic cause of office “fomo” – fear of missing out. It soon develops its Harlequinade, the bad jokesmith, the unstoppable talker, the maddening interrupter, the toadies, bad-mouthers, extroverts and those who just sit in silent despair. None is producing goods or services. In short the meeting is the office as religion. Its sacraments, creeds and acolytes are found in agendas, minutes and note-takers. Its liturgy is the canticle of the PowerPoint. The modern office even has its ritual sanctuary, the “meeting room”: 11.00 for matins, 2.30 for vespers.

Describing meetings as “secret killers of productivity”, Forbes magazine recently suggested they be simply banned, or held “only on Wednesdays” – all other decisions to be taken in absentia. Anyone who needs to be consulted – the “coordination” role of meetings – will find out soon enough. If not they don’t really need to know. The few brave organisations that have experimented with this drastic step report phenomenal improvements in workrate. One worker who said that if he missed a meeting, “my boss would probably kill me”, was told: “In that case he probably should.”

The number, length and size of meetings must be a sound Parkinsonian indicator of an organisation’s productivity or decay. The FTSE or the government should publish an annual league table of meetings per employee per week. It would illustrate the thesis by economist Joseph Schumpeter that all organisations have a natural lifecycle: they grow, they fatten, they ossify into meetings, and they die – unless funded by the state.

I bet Apple had few meetings in the early Steve Jobs days, but I bet it has thousands now. If so, as Parkinson warned of all who broke his laws, sell the shares. As for that meeting, skip it – and live.

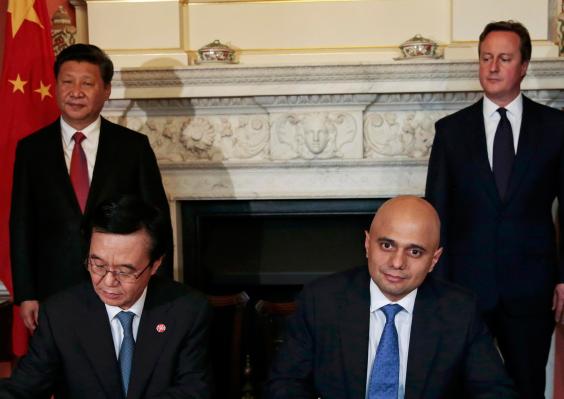

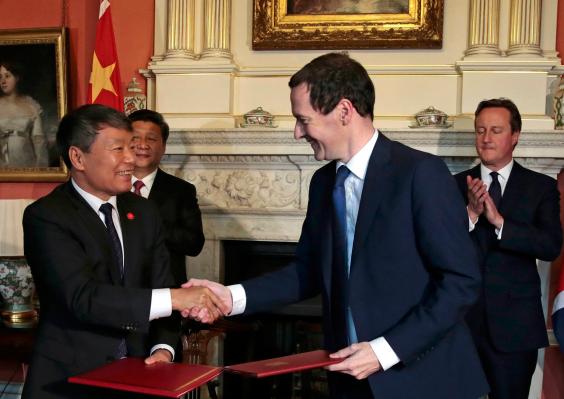

Xi Jinping and David Cameron attend a joint press conference in 10 Downing Street Suzanne Plunkett - WPA Pool/Getty Images

Xi Jinping and David Cameron attend a joint press conference in 10 Downing Street Suzanne Plunkett - WPA Pool/Getty Images