While many agree that private education is at the root of inequality in Britain, open discussion about the issue remains puzzlingly absent. In their new book, historian David Kynaston and economist Francis Green set out the case for change in The Guardian

The existence in Britain of a flourishing private-school sector not only limits the life chances of those who attend state schools but also damages society at large, and it should be possible to have a sustained and fully inclusive national conversation about the subject. Whether one has been privately educated, or has sent or is sending one’s children to private schools, or even if one teaches at a private school, there should be no barriers to taking part in that conversation. Everyone has to live – and make their choices – in the world as it is, not as one might wish it to be. That seems an obvious enough proposition. Yet in a name-calling culture, ever ready with the charge of hypocrisy, this reality is all too often ignored.

For the sake of avoiding misunderstanding, we should state briefly our own backgrounds and choices. One of our fathers was a solicitor in Brighton, the other was an army officer rising to the rank of lieutenant-colonel; we were both privately educated; we both went to Oxford University; our children have all been educated at state grammar schools; in neither case did we move to the areas (Kent and south-west London) because of the existence of those schools; and in recent years we have become increasingly preoccupied with the private-school issue, partly as citizens concerned with Britain’s social and democratic wellbeing, partly as an aspect of our professional work (one as an economist, the other as a historian).

In Britain, private schools – including their fundamental unfairness – remain the elephant in the room. It would be an almost immeasurable benefit if this were no longer the case. Education is different. Its effects are deep, long-term and run from one generation to the next. Those with enough money are free to purchase and enjoy expensive holidays, cars, houses and meals. But education is not just another material asset: it is fundamental to creating who we are.

What particularly defines British private education is its extreme social exclusivity. Only about 6% of the UK’s school population attend such schools, and the families accessing private education are highly concentrated among the affluent. At every rung of the income ladder there are a small number of private-school attenders; but it is only at the very top, above the 95th rung of the ladder – where families have an income of at least £120,000 – that there are appreciable numbers of private-school children. At the 99th rung – families with incomes upwards of £300,000 – six out of every 10 children are at private school. A glance at the annual fees is relevant here. The press focus tends to be on the great and historic boarding schools – such as Eton (basic fee £40,668 in 2018–19), Harrow (£40,050) and Winchester (£39,912) – but it is important to see the private sector in the less glamorous round, and stripped of the extra cost of boarding. In 2018 the average day fees at prep schools were, at £13,026, around half the income of a family on the middle rung of the income ladder. For secondary school, and even more so sixth forms, the fees are appreciably higher. In short, access to private schooling is, for the most part, available only to wealthy households. Indeed, the small number of income-poor families going private can only do so through other sources: typically, grandparents’ assets and/or endowment-supported bursaries from some of the richest schools. Overwhelmingly, pupils at private schools are rubbing shoulders with those from similarly well-off backgrounds.

They arrange things somewhat differently elsewhere: among affluent countries, Britain’s private‑school participation is especially exclusive to the rich. In Germany, for instance, it is also low, but unlike in Britain is generously state-funded, more strongly regulated and comes with modest fees. In France, private schools are mainly Catholic schools permitted to teach religion: the state pays the teachers and the fees are very low. In the US there is a very small sector of non-sectarian private schools with high fees, but most private schools are, again, religious, with much lower fees than here. Britain’s private-school configuration is, in short, distinctive.

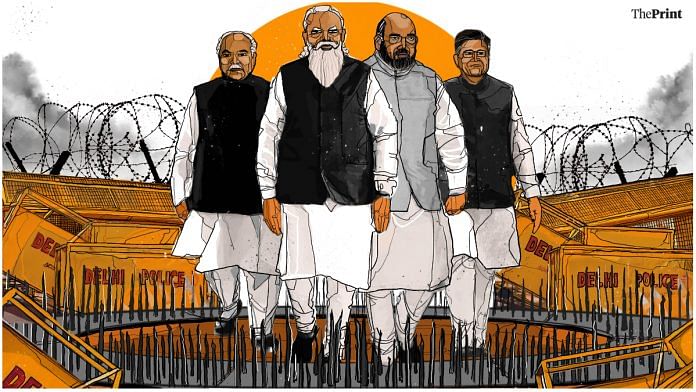

Some of the public figures of the past 20 years to have attended private schools (l-r from top): Tony Blair, former Bank of England governor Eddie George, Princess Diana, Prince Charles, Charles Spencer, businesswoman Martha Lane Fox, Dominic West, James Blunt, former Northern Rock chairman Matt Ridley, Boris Johnson, David Cameron, George Osborne, Jeremy Paxman, fashion journalist Alexandra Shulman, footballer Frank Lampard, Theresa May, Jeremy Corbyn and cricketer Joe Root. Composite: Rex, Getty

And so what, accordingly, does Britain look like in the 21st century? A brief but expensive history, 1997–2018, offers some guide. As the millennium approaches, New Labour under Tony Blair (Fettes) sweeps to power. The Bank of England under Eddie George (Dulwich) gets independence. The chronicles of Hogwarts school begin. A nation grieves for Diana (West Heath); Charles (Gordonstoun) retrieves her body; her brother (Eton) tells it as it is. Martha Lane Fox (Oxford High) blows a dotcom bubble. Charlie Falconer (Glenalmond) masterminds the Millennium Dome. Will Young (Wellington) becomes the first Pop Idol. The Wire’s Jimmy McNulty (Eton) sorts out Baltimore. James Blunt (Harrow) releases the bestselling album of the decade. Northern Rock collapses under the chairmanship of Matt Ridley (Eton). Boris Johnson (Eton) enters City Hall in London. The Cameron-Osborne (Eton-St Paul’s) axis takes over the country; Nick Clegg (Westminster) runs errands. Life staggers on in austerity Britain mark two. Jeremy Clarkson (Repton) can’t stop revving up; Jeremy Paxman (Malvern) still has an attitude problem; Alexandra Shulman (St Paul’s Girls) dictates fashion; Paul Dacre (University College School) makes middle England ever more Mail-centric; Alan Rusbridger (Cranleigh) makes non-middle England ever more Guardian-centric; judge Brian Leveson (Liverpool College) fails to nail the press barons; Justin Welby (Eton) becomes top mitre man; Frank Lampard (Brentwood) becomes a Chelsea legend; Joe Root (Worksop) takes guard; Henry Blofeld (Eton) spots a passing bus. The Cameron-Osborne axis sees off Labour, but not Boris Johnson+Nigel Farage (Dulwich)+Arron Banks (Crookham Court). Ed Balls (Nottingham High) takes to the dance floor. Theresa May (St Juliana’s) and Jeremy Corbyn (Castle House prep school) face off. Prince George (Thomas’s Battersea) and Princess Charlotte (Willcocks) start school.

The statistics also tell a story. The proportion of prominent people in every area who have been educated privately is striking, in some cases grotesque. From judges (74% privately educated) through to MPs (32%), the numbers tell us of a society where bought educational privilege also buys lifetime privilege and influence. “The dogged persistence of the British ‘old boy”’ is how a 2017 study describes the traditional dominance of private-school alumni in British society. This reveals the fruits of exploring well over a century of biographical data in Who’s Who, that indispensable annual guide to the composition of the British elite. For those born between the 1830s and 1920s, roughly 50-60% went to private schools; for those born between the 1930s and 1960s, the proportion was roughly 45-50%. Among the new entrants to Who’s Who in the 21st century, the proportion of the privately educated has remained constant at around 45%. Going to one of the schools in the prestigious Headmasters’ and Headmistresses’ Conference (HMC) still gives a 35 times better chance of entering Who’s Who than if one has not attended an HMC school; while those attending the historic crème de la crème, the so-called Clarendon Schools (Charterhouse, Eton, Harrow, Merchant Taylors’, Rugby, St Paul’s, Shrewsbury, Westminster, Winchester), are 94 times more likely to join the elite than any ordinary British-educated person.

Even if one’s child never achieves celebrity, sending him or her to a private school is usually a shrewd investment – indeed, increasingly so, to judge by the relevant longitudinal studies of two different generations. Take first the cohort born in 1958: in terms of those with comparable social backgrounds, demographic characteristics and early tested skills, and different only in what type of school they attended when they were 11, by the time they were in their early 30s (around 1990) the privately educated were earning 7% more than the state-educated. Compare that with those born in 1970: by the same stage (the early 2000s), the gap between the two categories – again, similar in all other respects – had risen to 21% in favour of the privately educated.

The only realistic starting point for an analysis lies with the assertion that, in the modern era, most of these schools are of high quality, offering a good educational environment. They deploy very substantial resources; respect the need for a disciplined environment for learning; and give copious attention to generating a positive and therefore motivating experience. This argument – the resources point aside – is not an altogether easy one for the left to accept, against a background of it having historically been undecided whether (in the words of one Labour education minister’s senior civil servant in the 1960s) “these schools are so bloody they ought to be abolished, or so marvellous they ought to be made available to everyone”. We do not necessarily accept that all private schools are “marvellous”; but by and large we recognise that, in their own terms of fulfilling what their customers demand, they deliver the goods.

Above all, private schools succeed when it comes to preparing their pupils for public exams – the gateways to universities. In 2018 the proportion of private-school students achieving A*s and As at A-level was 48%, compared with a national average of 26%; while for GCSEs, in terms of achieving an A or grade seven or above, the respective figures were 63% and 23%. At both stages, GCSE and A-level, the gap is invariably huge.

A famous image of school privilege: Harrovians Peter Wagner and Thomas Dyson and local schoolboys George Salmon, Jack Catlin and George Young photographed outside Lord’s cricket ground in 1937 by Jimmy Sime. Photograph: Jimmy Sime/Allsport

There are, of course, some very real contextual factors to these bald and striking figures. Any study must take account of where the children are coming from. Nevertheless, the picture presented by several studies is one of relatively small but still significant effects at every stage of education; and over the course of a school career, the cumulative effects build up to a notable gain in academic achievements.

Yet academic learning and exam results are not all there is to a quality education, and indeed there is more on offer from private schools. At Harrow, for example, its vision is that the school “prepares boys… for a life of learning, leadership, service and personal fulfilment”. It offers “a wide range of high-level extracurricular activities, through which boys discover latent talent, develop individual character and gain skills in leadership and teamwork”. Lesser-known schools trumpet something similar. Cumbria’s Austin Friars, for example, highlights a well-rounded education, proclaiming that its alumni will be “creative problem-solvers… effective communicators… and confident, modest and articulate members of society who embody the Augustinian values of unity, truth and love...”

If, on the whole, Britain’s private schools provide a quality education in both academic and broader terms, how do they deliver that? Four areas stand out.

First, especially small class sizes are a major boon for pupils and teachers alike. Second, the range of extracurricular activities and the intensive cultivation of “character” and “confidence” are important. Third, the high – and therefore exclusive – price tag sustains a peer group of children mainly drawn from supportive and affluent families. And fourth, to achieve the best possible exam results and the highest rate of admission to the top universities, “working the system” comes into play. Far greater resources are available for diagnosing special needs, challenging exam results and guiding university applications. Underpinning all these areas of advantage are the high revenues from fees: Britain’s private schools can deploy resources whose order of magnitude for each child is approximately three times what is available at the average state school.

The relevant figures for university admissions are thus almost entirely predictable. Perhaps inevitably, by far the highest-profile stats concern Oxbridge, where between 2010 and 2015 an average of 43% of offers from Oxford and 37% from Cambridge were made to privately educated students, and there has been no sign since of any significant opening up. Top schools, top universities: the pattern of privilege is systemic, and not just confined to the dreaming spires. Going to a top university, it hardly needs adding, signals a material difference, especially in Britain where universities are quite severely ranked in a hierarchy.

Ultimately, does any of this matter? Why can one not simply accept that these are high-quality schools that provide our future leaders with a high-quality education? Given the thorniness – and often invidiousness – of the issue, it is a tempting proposition. Yet for a mixture of reasons – political and economic, as well as social – we believe that the issue represents in contemporary Britain an unignorable problem that urgently needs to be addressed and, if possible, resolved. The words of Alan Bennett reverberate still. Private education is not fair, he famously declared in June 2014 during a sermon at King’s College Chapel, Cambridge. “Those who provide it know it. Those who pay for it know it. Those who have to sacrifice in order to purchase it know it. And those who receive it know it, or should.”

Consider these three fundamental facts: one in every 16 pupils goes to a private school; one in every seven teachers works at a private school; one pound in every six of all school expenditure in England is for the benefit of private-school pupils.

The crucial point to make here is that although extra resources for each school (whether private or state) are always valuable, that value is at a diminishing rate the wealthier the school is. Each extra teacher or assistant helps, but if you already have two assistants in a class, a third one adds less value than the second. Given the very unequal distribution of academic resources entailed by the British private school system, it is unarguable that a more egalitarian distribution of the same resources would enhance the total educational achievement. There is, moreover, the sheer extravagance. Multiple theatres, large swimming pools and beautiful surroundings with expensive upkeep are, of course, nice to have and look suitably seductive on sales brochures – but add relatively little educational value.

Further inefficiency arises from education’s “positional” aspect. The resources lift up children in areas where their rank position on the ladder of success matters, such as access to scarce places at top universities. To the considerable extent this happens, the privately educated child benefits but the state-educated child loses out. This lethal combination of private benefit and public waste is nowhere more apparent than in the time and effort that private schools devote to working the system, to ease access to those scarce places.

What about the implications for our polity? The way the privately educated have sustained semi-monopolistic positions of prominence and influence in the modern era has created a serious democratic deficit. The unavoidable truth is that, by and large, the increasingly privileged and entitled products of an elite private education have – almost inevitably – only a limited and partial understanding of, and empathy with, the realities of everyday life as lived by most people. One of those realities is, of course, state education. It marked some kind of apotheosis when in July 2014 the appointment of Nicky Morgan (Surbiton High) as education secretary meant that every minister in her department at that time was privately educated.

On social mobility, there has been in recent years an abundance of apparently sincere, well-meaning rhetoric, not least from our leading politicians. “Britain has the lowest social mobility in the developed world,” laments David Cameron in 2015. “Here, the salary you earn is more linked to what your father got paid than in any other major country. We cannot accept that.” In 2016 Jeremy Corbyn declares his movement will “ensure every young person has the opportunities to maximise their talents”, while Theresa May follows on: “I want Britain to be a place where advantage is based on merit not privilege; where it’s your talent and hard work that matter, not where you were born, who your parents are or what your accent sounds like.” Rather like corporate social responsibility in the business world, social mobility has become one of those motherhood-and-apple-pie causes that it is almost rude not to utter warm words about.

Yet the mismatch between such sentiments and policymakers’ practical intentions is palpable. The Social Mobility Commission, with cross-party representation, reported regularly on what government should do, but in December 2017 all sitting members resigned in frustration at the lack of policy action in response to their recommendations.

The underlying reality of our private-school problem is stark. Through a highly resourced combination of social exclusiveness and academic excellence, the private-school system has in our lifetimes powered an enduring cycle of privilege. It is hard to imagine a notable improvement in our social mobility while private schooling continues to play such an important role. Allowing, as Britain still does, an unfettered expenditure on high-quality education for only a small minority of the population condemns our society in seeming perpetuity to a damaging degree of social segregation and inequality. This hands-off approach to private schools has come to matter ever more, given over the past half-century the vastly increased importance in our society of educational credentials. Perhaps once it might have been conceivable to argue that private education was a symptom rather than a cause of how privilege in Britain was transferred from one generation to the next, but that day is long gone: the centrality of schooling in both social and economic life – and the Noah’s flood of resources channelled into private schools for the few – are seemingly permanent features of the modern era. The reproduction of privilege is now tied in inextricably with the way we organise our formal education.

Ineluctably, as we look ahead, the question of fairness returns. If private schooling in Britain remains fundamentally unreconstructed, it will remain predominantly intended and destined for the advantage of the already privileged children who attend.

We need to talk openly about this problem, and it is time to find some answers. Some call for the “abolition” of private schools – whatever that might mean. We do not call for that, because we think it is better – and feasible – to harness for all the good qualities of private schools. Feasible reforms are available; these do not require excessive commitments from the Treasury, but do require a political commitment.

We are, however, under no illusions about the task of reform. The schools’ links with powerful vested interests are close and continuous. London’s main clubs (dominated by privately educated men) would be one example; the Church of England (closely connected with many private schools, from Westminster downwards) would be another. Or take the City of London, where in that historic and massively wealthy square mile not only do individual livery companies have an intimate involvement with a range of private schools, but the City corporation itself supports an elite trio in Surrey and London (City of London, City of London school for girls, City of London Freemen’s school). While as for the many hundreds of individual links between “top people” and private schools, often in the form of sitting on governing bodies, it only needs a glance at Who’s Who to get the gist. The term “the establishment” can be a tiresome one, too often loosely and inaccurately used, but in the sense of complementary networks of people at or close to the centres of power and wealth, it actually does mean something.

All of which leaves the private schools almost uniquely well placed to make their case and protect their corner. They have ready access to prominent public voices speaking on their behalf, especially in the House of Lords; they enjoy the passive support of the Church of England, which is distinctly reluctant to draw attention to the moral gulf between the aims of ancient founders and the socioeconomic realities of the present; and of course, they have no qualms about utilising all possible firepower, human as well as media and institutional, to block anything they find threatening.

The great historian EP Thompson wrote more than half a century ago about The Peculiarities of the English. Historically, those peculiarities have been various, but the most important – and pervasive in its consequences – has been social class. Of course, things to a degree have changed since Thompson’s time. The visible distinctions of dress and speech have been somewhat eroded, if far from obliterated; the obvious social manifestations of a manufacturing economy have been replaced by the more fluid forms of a service economy; the increasing emphasis of reformers and activists has been on issues of gender and ethnicity; and a series of politicians and others have sought to assure us that we are moving into “a classless society”. Yet the fundamental social reality remains profoundly and obstinately otherwise. Britain is still a place where more often than not it matters crucially not only to whom one has been born, but where and in what circumstances one has grown up.

It would be manifestly absurd to pin the blame entirely on the existence over the past few centuries of a flourishing private-school sector. Even so, given that these schools have been and still are places that – when the feelgood verbiage is stripped away – ensure that their already advantaged pupils retain and extend their socio‑economic advantages in later life, common sense places them squarely in the centre of the frame.

Is it possible in Britain over the next 10 or 20 years to build a sufficiently widespread consensus for reform? Or, at the very least, to begin to have a serious, sustained, non-name-calling, non-guilt-ridden national conversation on the subject of private education? A poll we commissioned from Populus shows a virtually landslide majority for a perception of unfairness about private education, indicating that public opinion is potentially receptive to grappling with the issue and what to do about it. The poll reveals, moreover, that even those who have been privately educated, or have chosen to educate their own children privately, are more likely than not to have a perception of unfairness.

The question of what to do about a sector educating only some 6% of our school population might seem relatively trifling, and difficult to prioritise (especially in challenging economic circumstances), compared with say the challenges of quality teacher recruitment across the state sector or the whole vital area of early-years learning. Yet it would be a huge mistake to underestimate the seriously negative educational aspects of the current dispensation and to continue to marginalise the private-school question. The private schools’ reach is very much broader than their minority share of school pupils implies. Unless some radical reform is set in train, an unreconstructed private-school system, with its enormous resource superiority and exclusiveness hanging over the state system as a beacon for unequal treatment and privilege, would make it hard to sustain a fully comprehensive and fair state education system.

Ultimately, the issue is at least as much about what kind of society one might hope the Britain of the 2020s and 2030s to be. A more open society in which upward social mobility starts to become a real possibility for many children, not just a few lucky ones? A society in which the affluent are not educated in enclaves, and in which schooling for the affluent is not funded at something like three times the level of schooling for the less affluent? A society in which the pursuit through education of greater equality of life chances, seeking to harness the talents of all our children, is a matter of real and rigorous intent? A society in which there is a just relationship between the competing demands of liberty and equity, and in which we are, to coin a phrase, all in it together? For the building of such a society, or anything even remotely close, the issue of private education is pivotal, both symbolically and substantively. The reform of private schools will not alone be sufficient to achieve a good education system for all, let alone the good society; but it surely is a necessary condition. At this particular moment in our island story, the future seems peculiarly a blank sheet. Everything is potentially on the table. And for once, that has to include the engines of privilege. For if not now, when?

• Engines of Privilege: Britain’s Private School Problem by Francis Green and David Kynaston is published by Bloomsbury on 7 February (£20). To order a copy for £17.60 go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99

How to do it: feasible reform options

There are broadly two types of option: those that handicap private schools, making them less attractive to parents, and those that envisage “crossing the tracks” – some form of integration with the state-school sector. Some reforms would have much more of an impact than others.

1. Handicaps

Contextual admissions to universities Where universities, especially the high-status ones, make substantial allowances for candidates’ school background; alternatively, as another method of positive discrimination, some form of a quota system.

Upping the cost Where the fees are substantially raised, making some parents switch away from the private-school sector and opt for state schools. Even though tax subsidies are not huge, the government could reduce them, for example by taking away charitable status (from those schools that are charities) or by requiring that all schools pay business rates in full (as in Scotland from 2020).

Alternatively, something that would “hurt” a bit more, government could directly tax school fees (as in Labour’s manifesto pledge to impose VAT or in Andrew Adonis’s proposed 25% “educational opportunity tax”).

2. Crossing the tracks

There are several proposed schemes for enabling children from low-income families to attend private schools. Mainly, these would leave it to schools to choose how they select their pupils. Some are relatively small in scope, including a proposal from the Independent Schools Council that would involve no more than 2% of the private-school population. Others are more ambitious: the Sutton Trust’s Open Access Scheme proposes that all places at about 80 top private secondary day schools would be competed for on academic merit. The government would subsidise those who could not afford the fees.

In another type of partial integration, schools would select a proportion of state-funded pupils according to the Schools Admissions Code, meaning that the government or local government would set the principles for selection and the extra places would become an extension to the state system. We suggest a Fair Access Scheme, where the schools would be obliged initially to recruit one-third of their pupils in this way, with a view to the proportion rising significantly over time.