'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Punjab. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Punjab. Show all posts

Thursday, 21 September 2023

Friday, 17 June 2022

Monday, 31 January 2022

Thursday, 18 March 2021

Saturday, 6 February 2021

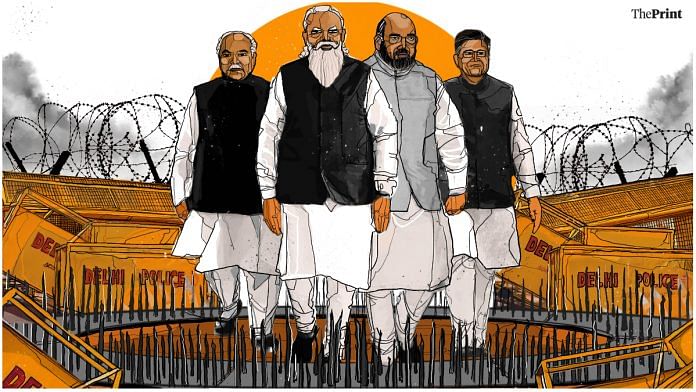

Modi govt has lost farm laws battle, now raising Sikh separatist bogey will be a grave error

Shekhar Gupta in The Print

Protests over the three farm reform laws are well into the third month now. There are six key facts, or facts as we see them, that we can list here:

1. The farm laws, by and large, are good for the farmers and India. At various points of time, most major political parties and leaders have wanted these changes. However, many of you might still disagree. But then, this is an opinion piece. I explained it in detail in this, Episode 571 of #CutTheClutter.

2. Whether the laws are good or bad for the farmer no longer matters. In a democracy, all that matters is what people affected by a policy change believe — in this case, the farmers of the northern states. Facts don’t matter if you’ve failed to convince them.

3. The Modi government is right when it says this is no longer about the farm laws. Because nobody is talking about MSP, subsidies, mandis and so on. Then what’s it about?

4. The short answer is, it is about politics. And why not? There is no democracy without politics. When the UPA was in power, the BJP opposed all its good ideas, from the India-US nuclear deal to FDI in insurance and pension. Now it’s implementing the same policies at the rate of, say, 6X.

5. As far as the farm laws are concerned, the Modi government has already lost the battle. Again, you can disagree. But this is my opinion. And I will make my case.

6. Finally, the Modi government has two choices. It can let it fester, expand into a larger political war. Or it can cut its losses and, as the Americans say, get off the kerb.

Here is the evidence that lets us say that the Modi government has lost the battle for these farm laws.

Protests over the three farm reform laws are well into the third month now. There are six key facts, or facts as we see them, that we can list here:

1. The farm laws, by and large, are good for the farmers and India. At various points of time, most major political parties and leaders have wanted these changes. However, many of you might still disagree. But then, this is an opinion piece. I explained it in detail in this, Episode 571 of #CutTheClutter.

2. Whether the laws are good or bad for the farmer no longer matters. In a democracy, all that matters is what people affected by a policy change believe — in this case, the farmers of the northern states. Facts don’t matter if you’ve failed to convince them.

3. The Modi government is right when it says this is no longer about the farm laws. Because nobody is talking about MSP, subsidies, mandis and so on. Then what’s it about?

4. The short answer is, it is about politics. And why not? There is no democracy without politics. When the UPA was in power, the BJP opposed all its good ideas, from the India-US nuclear deal to FDI in insurance and pension. Now it’s implementing the same policies at the rate of, say, 6X.

5. As far as the farm laws are concerned, the Modi government has already lost the battle. Again, you can disagree. But this is my opinion. And I will make my case.

6. Finally, the Modi government has two choices. It can let it fester, expand into a larger political war. Or it can cut its losses and, as the Americans say, get off the kerb.

Here is the evidence that lets us say that the Modi government has lost the battle for these farm laws.

First of all, there is the unilateral offer of an 18-month deferral to implementing the laws. Count 18 months from now, you will be left with only another 18 before the 2024 general elections.

You see even a Modi-Shah BJP is unlikely to risk reopening this front at that point. In fact, the bellwether heartland state elections, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan, will be exactly 12 months away. Two of them have strong Congress incumbents and in the third, the BJP has bought and stolen power. Nobody’s risking losing these to make their point over farm reforms. These laws, then, are as bad as dead in the water.

Again, unilaterally, the government has already made a commitment of continuing with Minimum Support Price (MSP), although there is nothing in the laws saying it will be taken away. With so much already given away, the battle over the farm laws is lost.

The Modi government’s challenge now is to buy normalcy without making it look like a defeat. We know that it got away with one such, with the new land acquisition law. But that issue was still confined to Parliament. This is on the streets, highway choke-points, and in the expanse of wheat and paddy all around Delhi. This can spread. If the government retreats in surrender, this issue may close, but politics will rage. And why not? What is democracy but competitive politics, brutal, fair and fun? The next targets will then be other reform measures, from the new labour laws to the public listing of LIC.

What are the errors, or blunders, that brought India’s most powerful government in 35 years here? I shall list five:

1. Bringing in these laws through the ordinance route was a blunder. I speak from 20/20 hindsight, but then I am a commentator, not a political leader. To usher in the promise of sweeping change affecting the lives of more than half a billion people, the correct way would have been to market the ideas first. We don’t know if Narendra Modi now regrets not having prepared the ground for it. But the fact is, people at the mass level would be suspicious of such change through ordinances. Especially if you aren’t talking to them.

2. The manner in which the laws were pushed through Rajya Sabha added to these suspicions. This needed better parliamentary craft than the blunt use of vocal chords. This helped fan the fire, or spread the ‘hawa’ that something terrible was being forced down the surplus-producing farmers’ throats.

3. The party was riding far too high on its majority to care about allies and friends. If it had taken them along respectfully, the passage through Rajya Sabha wouldn’t have been so ungainly. At least the Akalis should never have been lost. But, as we’ve said before, this BJP does not understand Punjab or the Sikhs.

4. It also underestimated the frustration among the Jats of Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh, disempowered by the Modi-Shah politics. The senior-most Jat leaders in the Modi council of ministers are both inconsequential ministers of state. One is from distant Barmer in Rajasthan. The most visible of them, Sanjeev Balyan, won from Muzaffarnagar, where the big pro-Tikait mahapanchayat was held. In Haryana, the BJP has no Jat who counts. On the contrary, it found the marginalisation of Jat power as its big achievement. It refused to learn even from statewide, violent Jat agitations for reservations. The anger then was rooted in political marginalisation, as it is now. Ask why the BJP’s Jat ally Dushyant Chautala, or any of its Jat MPs/MLAs in UP, especially Balyan, are not on the ground, marketing these reforms? They wouldn’t dare.

5. The BJP conceded too much, too soon, unilaterally in the negotiations. It doesn’t have much more to give now. And the farm leaders have conceded nothing.

In conclusion, where does the Modi government go from here? One approach could be to tire the farmers out. On all evidence, that is not about to happen. Rabi harvest in April is still nearly 75 days away, and with much work done by mechanical harvesters and migrant workers, families would be quite capable of keeping the pickets full.

The next expectation would be that the Jats would ultimately make a deal. This is plausible. Note the key difference between Singhu and Ghazipur. In the first, no politician can even go for a selfie. Ask Ravneet Singh Bittu of the Congress, who was turned out unceremoniously. But everybody can go to Ghazipur and be photographed hugging Tikait. The Congress, Left, RLD, RJD, AAP, all of them. Even Sukhbir Singh Badal comes to Ghazipur, instead of Singhu to meet his fellow Sikhs from Punjab. Wherever there is politics and politicians, conflict resolution is possible. But what happens if this becomes a reality?

This will leave India and the Modi government with the most dangerous outcome of all. It will corner the Sikhs of Punjab. Already, the lousy barricading visuals and government’s prickly response to something as trivial as some celebrity tweets is threatening to redefine the issue from farm laws to national unity. The Modi government will err gravely if it changes the headline from farm protests to Sikh separatism.

This crisis requires political sophistication and governance skills. This BJP has neither. It has, instead, political skills and governance by clout, riding an all-conquering election-winning machine. It is the party’s inability to accept the realities of Indian politics and appreciate the limitations of a parliamentary majority that brought it here.

Does it have the smarts and sagacity to negotiate its way out of it? We can’t say. But we hope it does. Because the last thing India needs is to start another war for national unity. You would be nuts to reopen an issue in Punjab we all closed and buried by 1993.

You see even a Modi-Shah BJP is unlikely to risk reopening this front at that point. In fact, the bellwether heartland state elections, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan, will be exactly 12 months away. Two of them have strong Congress incumbents and in the third, the BJP has bought and stolen power. Nobody’s risking losing these to make their point over farm reforms. These laws, then, are as bad as dead in the water.

Again, unilaterally, the government has already made a commitment of continuing with Minimum Support Price (MSP), although there is nothing in the laws saying it will be taken away. With so much already given away, the battle over the farm laws is lost.

The Modi government’s challenge now is to buy normalcy without making it look like a defeat. We know that it got away with one such, with the new land acquisition law. But that issue was still confined to Parliament. This is on the streets, highway choke-points, and in the expanse of wheat and paddy all around Delhi. This can spread. If the government retreats in surrender, this issue may close, but politics will rage. And why not? What is democracy but competitive politics, brutal, fair and fun? The next targets will then be other reform measures, from the new labour laws to the public listing of LIC.

What are the errors, or blunders, that brought India’s most powerful government in 35 years here? I shall list five:

1. Bringing in these laws through the ordinance route was a blunder. I speak from 20/20 hindsight, but then I am a commentator, not a political leader. To usher in the promise of sweeping change affecting the lives of more than half a billion people, the correct way would have been to market the ideas first. We don’t know if Narendra Modi now regrets not having prepared the ground for it. But the fact is, people at the mass level would be suspicious of such change through ordinances. Especially if you aren’t talking to them.

2. The manner in which the laws were pushed through Rajya Sabha added to these suspicions. This needed better parliamentary craft than the blunt use of vocal chords. This helped fan the fire, or spread the ‘hawa’ that something terrible was being forced down the surplus-producing farmers’ throats.

3. The party was riding far too high on its majority to care about allies and friends. If it had taken them along respectfully, the passage through Rajya Sabha wouldn’t have been so ungainly. At least the Akalis should never have been lost. But, as we’ve said before, this BJP does not understand Punjab or the Sikhs.

4. It also underestimated the frustration among the Jats of Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh, disempowered by the Modi-Shah politics. The senior-most Jat leaders in the Modi council of ministers are both inconsequential ministers of state. One is from distant Barmer in Rajasthan. The most visible of them, Sanjeev Balyan, won from Muzaffarnagar, where the big pro-Tikait mahapanchayat was held. In Haryana, the BJP has no Jat who counts. On the contrary, it found the marginalisation of Jat power as its big achievement. It refused to learn even from statewide, violent Jat agitations for reservations. The anger then was rooted in political marginalisation, as it is now. Ask why the BJP’s Jat ally Dushyant Chautala, or any of its Jat MPs/MLAs in UP, especially Balyan, are not on the ground, marketing these reforms? They wouldn’t dare.

5. The BJP conceded too much, too soon, unilaterally in the negotiations. It doesn’t have much more to give now. And the farm leaders have conceded nothing.

In conclusion, where does the Modi government go from here? One approach could be to tire the farmers out. On all evidence, that is not about to happen. Rabi harvest in April is still nearly 75 days away, and with much work done by mechanical harvesters and migrant workers, families would be quite capable of keeping the pickets full.

The next expectation would be that the Jats would ultimately make a deal. This is plausible. Note the key difference between Singhu and Ghazipur. In the first, no politician can even go for a selfie. Ask Ravneet Singh Bittu of the Congress, who was turned out unceremoniously. But everybody can go to Ghazipur and be photographed hugging Tikait. The Congress, Left, RLD, RJD, AAP, all of them. Even Sukhbir Singh Badal comes to Ghazipur, instead of Singhu to meet his fellow Sikhs from Punjab. Wherever there is politics and politicians, conflict resolution is possible. But what happens if this becomes a reality?

This will leave India and the Modi government with the most dangerous outcome of all. It will corner the Sikhs of Punjab. Already, the lousy barricading visuals and government’s prickly response to something as trivial as some celebrity tweets is threatening to redefine the issue from farm laws to national unity. The Modi government will err gravely if it changes the headline from farm protests to Sikh separatism.

This crisis requires political sophistication and governance skills. This BJP has neither. It has, instead, political skills and governance by clout, riding an all-conquering election-winning machine. It is the party’s inability to accept the realities of Indian politics and appreciate the limitations of a parliamentary majority that brought it here.

Does it have the smarts and sagacity to negotiate its way out of it? We can’t say. But we hope it does. Because the last thing India needs is to start another war for national unity. You would be nuts to reopen an issue in Punjab we all closed and buried by 1993.

Wednesday, 30 January 2013

Green Books, red herring and the LoC war

PRAVEEN SWAMI

Photo: PTIFOCUS: India must become aware that a more muscular response to Pakistani aggression on the LoC will come with a price that probably isn’t worth paying. The picture is of commanders of the Indian and Pakistani Armies at a flag meeting in Poonch recently.

Pakistan’s military literature makes clear that its generals are seeking to provoke a crisis. India is pushing itself into their trap

Late one night in the summer of 2009, four improvised 107-millimetre rockets arced over the Pul Kanjari border outpost in Punjab, and exploded in the fields outside the village of Attari. For the first time since the war of 1971, there was an attack across the India-Pakistan border. In September that year, four more rockets were fired; then, in January 2010, there was a third assault.

Now, as Indian and Pakistani troops trade fire along the Line of Control (LoC), it is more important than ever to understand the significance of those events. The rocket attacks, believed to have been carried out by the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, represented a glimpse into a grim future that India’s policy of strategic restraint has been designed to avert — a war of attrition waged by jihadists that would turn India’s western frontiers into a kind of nuclear-fuelled Lebanon.

Ever since January 2008, two months after General Pervez Ashfaq Kayani took over as chief of the Pakistan Army, clashes along the LoC have escalated. India reported 28 ceasefire violations in 2009, 44 in 2010, 60 in 2011, and 117 last year. The traditional explanation — that these clashes are linked to terrorist infiltration across the LoC — borne out by the data: during this period, Jammu and Kashmir has become significantly less violent, not more.

New doctrine

Pakistan’s military literature provides some insight into what is going on. The country’s generals, it shows, hope heightened tensions with India will help rebuild their legitimacy, extricate themselves from a domestic insurgency they are losing, and push jihadist groups now ranged against the Pakistani state to turn their energies eastwards. India, driven by a barrage of ill-conceived war polemic, is pushing itself into this trap.

Earlier this month, reports emerged that Pakistan had amended its doctrinal manual, called the Green Book, to include a chapter identifying internal insurgent forces as the country’s principal national security threat. No one, though, has quoted as much as a single line from the Green Book in question — one of several reasons to suspect it might just be a red herring. Pakistani Prime Minister Raja Pervez Ashraf, in a January 4 address at the National Defence University, called on the armed forces to “redesign and redefine our military doctrine” to fight terrorism. It seems reasonable to infer that, on that date, he at least was unaware of a new doctrine.

C. Christine Fair, a Georgetown University scholar who is the preeminent authority on the Pakistan Army’s internal doctrinal literature — and the first to bring the Green Book series to light — is in little doubt that is the case. “This talk of a new doctrine is rubbish,” says Dr. Fair, “I think a lot of people who really ought know better have let themselves be talked into buying snake-oil.”

The Green Book isn’t, in fact, a doctrinal testament — or even, in fact, one book. For the last two decades, as first reported in The Hindu in 2011, the Pakistan Army’s general headquarters has published collections of essays by senior officers, with the name assigned to the series. The 2010 Green Book, on information warfare, only became available last year; the next in the biennial series only became available in 2011.

Suspicions of India

From the very first essay in the current Green Book, it becomes clear the Pakistani officer corps’ maniacal suspiciousness of India hasn’t stilled. Brigadier Umar Farooq Durrani’s “Treatise on Indian-backed Psychological Warfare Against Pakistan,” asserts that the Research and Analysis Wing “funds many Indian newspapers and even television channels, such as Zee Television, which is considered to be its media headquarters to wage psychological war.” The “creation of [the] South Asian Free Media Association a few years back,” Brigadier Farooq claims, “was a step in the same direction.” Even the eminent scholar Ayesha Siddiqa’s work, he insists, is “a classical example of psychological war against Pakistan.”

“The most subtle form” of this psychological war, the Brigadier states, “is found in movies where Muslim and Hindu friendship is screened within [sic.] the backdrop of melodrama. Indian soaps and movies are readily welcomed in most households in Pakistan. The effects desired to be achieved through this is to undermine the Two National Theory [as] being a person obsession of [Muhammad Ali] Jinnah.”

Had the Green Books not been official publications, none of this ought to have been a cause of worry. There is, after all, no shortage of delusional paranoiacs on the eastern side of the India-Pakistan border either, in and outside the armed forces.

From the Pakistan Army chief himself, though, we know ideas like those of Brigadier Durrani are considered worthy of serious consideration. In his foreword to the 2010 edition, General Kayani asserts that the essays provide “an effective forum for the leadership to reflect on, identity and define the challenges faced by the Pakistan army, and share possible ways of overcoming them.”

The eastern enemy

Language of the kind that runs through the 2010 Green Book pervades earlier editions too. In 2002, as Pakistan faced up to the looming war between its armed forces and their one-time jihadist allies, theGreen Book focussed on low-intensity warfare. Brigadier Shahid Hashmat, typically, argued that the “threat of low-intensity conflicts should be considered as the most serious matter at [the] national level.” Thus, he went on, “all national agencies and resources must be directed concurrently for launching an effective and robust response against this threat.”

The blame for the crisis imposed on Pakistan by religious sectarian groups and jihadists, though, is firmly placed on India. Lieutenant-Colonel Inayatullah Nadeem Butt, using ideas near-identical to those in the current Green Book, asserted that “India has been aggressively involved in subverting the minds of youth through planned propaganda and luring them towards subversive activities.”

Even as they considered how to fight religious sectarian groups and revolutionary jihadists, the officers who contributed to the 2002 Green Book thus focussed on imposing punitive costs on India. Brigadier Muhammad Zia, for example, noted that “India is highly volatile on its internal front due to numerous vulnerabilities which, if agitated, accordingly could yield results out of proportion to the efforts put in.” In similar vein, Major Ijaz Ahmad advocated “that [the] Inter-Services Intelligence should launch low profile operations in Indian-held Kashmir and should not allow the freedom movement to die down.” “Linguistic, social, religious and communal diversities in India,” the officer continued, “should be exploited carefully and imaginatively.”

Put another way, even as they considered tactics to defeat insurgents in Pakistan, the officer corps also discussed sponsoring insurgencies in India, to tie down their arch-adversary. General Pervez Musharraf described the 2002 Green Book, as a “valuable document for posterity”; he was right.

Tough challenge

Like all forms of madness, the texts in the Green Book aren’t without method: crisis with India is, after all, a precondition for ensuring the Pakistan Army’s preeminent position in the country’s power structure. 26/11, it is surprisingly little remarked upon, almost did pay off for Pakistan’s Army. Less than a week after the attack, a senior Army commander was reported as calling the jihadist chief Baitullah Mehsud a “patriot.” The officer said the army’s war with the Taliban leaders like Mehsud was merely the result of minor “misunderstandings.”

There is plenty of evidence that jihadists in Pakistan are growing more powerful — and that organisations like the Tehreek-e-Taliban are seriously considering expanding their operations eastwards. “The practical struggle for a shari’a system that we are carrying out in Pakistan,” its deputy chief Maulana Wali-ur-Rahman said in a recently-released video, “the same way we will continue it in Kashmir, and the same way we will implement the shari’a system in India.”

It is self-evident that preventing a rapprochement between jihadists and the generals is in India’s best interest — one reason why Prime Ministers Atal Behari Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh proved willing to pay the political price for a policy of strategic restraint. That the will to continue doing so is fraying in the build-up to the General Election is evident. India has, so far, punished Pakistani aggression with a variety of means, conventional and covert — but the seduction of grandiose gestures is growing. Indians must become aware, though, that a more muscular response to Pakistani aggression on the LoC, like all instant gratification, will come with a price that probably isn’t worth paying.

praveen.swami@thehindu.co.in

Wednesday, 19 December 2007

Poison Earth

Poison Earth

Courtesy an overzealous Green Revolution, Punjab has poison in its water and a cancer epidemic on its hands

CHANDER SUTA DOGRA The Curse Is Spreading

On death row: Jajjal's Karnail Singh and his wife both have cancer, live in adjoining houses, each with a son

In Ghaunzpur in Ludhiana district, a good 200 km away, Manjit and Gurjit Singh lost both their parents to hepatitis; an uncle is afflicted with the same. The water from the hand pump in the courtyard turns foamy when heated, so they have dug a submersible pump which pumps out water from 300 ft below. Other households in the village cannot afford to do so.

For Punjab's prosperous farming households and lush green fields, the famed Green Revolution is beginning to turn bilious from within. Its gushing tubewells, the cattle heavy with milk, the trolleys laden with vegetables destined for urban markets—all are likely to be contaminated with toxins. The state is sitting on an environmental crisis and few of have any idea of how to tackle it.

Some two years ago, when reports of increased cancer deaths first started coming in from the state's cotton belt, the Chandigarh-based Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER) decided to investigate. A preliminary study it conducted found a much higher prevalence of cancer in the Talwandi Sabo block and the presence of heavy metals and pesticides in drinking water in the area. It recommended a comprehensive study of the status of environmental health in Punjab's other cotton-growing areas, the setting up of a cancer registry in the state, and regular monitoring of the drinking water. Of course, intense pressure from the pesticides lobby ensured none of this came to pass and the report was ignored.

This month, the PGIMER's department of community medicine has submitted a comprehensive epidemiological study (see box) in areas along the state's five major rivulets to the State Pollution Control Board. The results are so shocking that the board has put it under wraps and is having second thoughts about releasing it. Says Dr J.S. Thakur, an assistant professor at PGIMER, who conducted the study, "Our two studies show that all of Punjab is toxic and people do not have safe water to drink. Both agricultural and industrial malpractices are to be blamed for this."

The worst affected is the southeastern Malwa region, better known these days as the 'cancer belt'. To counter increasingly resistant pests, farmers here spray their fields with pesticide doses far above those recommended—often cocktailing two or more chemicals. As the former sarpanch of Jajjal, Najar Singh, told Outlook, "Although the recommended dose is about five sprays per season, we sometimes spray our fields 25 to 30 times. Almost every third day!" Punjab, which makes up for just 2.5 per cent of the country's area, accounts for 18 per cent of the pesticides used in the country.

The state's problem is their unregulated use, say experts, with most farmers unaware of how to use or dispose of the empty pesticide cans. So, in the last four decades pesticides have seeped into the underground water aquifers, as also in the state's water bodies. And in the last 10 years, more and more well-off households along the drains have begun setting up submersible pumps to get water from deep aquifers, as water from taps and handpumps is unfit for human use.

Punjab's finance minister Manpreet Badal is a legislator from Muktsar district's Gidderbaha, located in the cancer belt. "In the 50 villages in my constituency," he says, "there'd be a thousand-odd cancer cases. I've lost count of the funerals of cancer victims I've attended in my area since the beginning of this year. It is an epidemic here." A train leaving from Bhatinda to Bikaner has been dubbed 'cancer express' as most patients from here go to Bikaner's cancer hospital for treatment. Even a child in these parts knows what chemotherapy is about. "Our neighbour used to take hot injections before she died last year," says little Kiranjot at Chandbaja village in Faridkot district. "Many others in our village have taken them."

Giana's Baljeet Kaur has cancer of the oesophagus

Dr G.P.I. Singh, who heads the department of community medicine in Ludhiana's Dayanand Medical College, has recently begun studying, along with other private doctors across the state and NGO Kheti Virasat Mission (KVM), the impact of heavy metals and pesticides on reproductive health in Punjab. "One of the things worrying us," he says, "is that the skewed sex ratio in both Punjab and Haryana could also be due to chemical exposure, as the female foetus is more vulnerable. We notice an increase in spontaneous abortions, infertility, distorted menarche and foetuses with neural tube defects." There is also a high incidence of grey hair among children and young adults in this area. Ask for one, and most villages throw up several.

Not just pesticides, but unchecked effluent flow from industries into the rivers and drains too has contaminated underground water in Punjab. At Ghaunzpur, for instance, five paper mills dump their entire effluent unchecked into the Buddha Nullah. However, the state pollution board which is supposed to check industries such as these from polluting water bodies couldn't be bothered. This is evident from the response of the board's chairman, Yogesh Goel, when queried about the PGIMER report."I'm busy right now. You can ask the secretary of the board about it," he told Outlook. Quite predictably, the secretary too made himself unavailable. KVM director Umendra Dutt, who has been most active in raising the issue of cancer deaths in Punjab, feels that agricultural scientists in cahoots with pesticide manufacturing mncs have led to this health crisis. "All these years agricultural scientists have been advocating heavy doses of pesticides without informing farmers of the damage improper usage causes," he says.

Meanwhile, though officials are aware of the problem, the state is yet to evolve a concrete water policy to address the problem. Says J.R. Kundal, Punjab's secretary for water supply and sanitation, "Ideally, there should be an umbrella task force to deal with the problem in its entirety," he says. "Presently, different agencies are conducting overlapping studies which will take us nowhere. I am heading a task force to study arsenic in water, while the state planning board is looking into drinking water and allied issues. Although 90 per cent of the underground water is used for irrigation and just 10 per cent for drinking water, we realise that this 10 per cent is crucial for the health of our people."

With the government unsure of what to do, Manpreet Badal has installed four distribution points supplying Reverse Osmosis water in his constituency. "Till a statewide water supply scheme comes up," says he, "I've taken this interim measure." His people are lucky. Others in the state are condemned to drinking polluted water and suffer from deadly diseases, reaping the poisoned fruit of a Green Revolution gone unchecked.

Everything in one place… All new Windows Live!

Courtesy an overzealous Green Revolution, Punjab has poison in its water and a cancer epidemic on its hands

CHANDER SUTA DOGRA The Curse Is Spreading

- The Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research in Chandigarh has conducted a study over two years in five villages along Punjab's major rivulets in Jalandhar, Ludhiana, Amritsar districts

- 88 per cent ground water samples showed alarming levels of mercury, over 50 per cent samples of ground and tap water contaminated by arsenic

- Lady's fingers, carrots, gourds, cauliflower and chillies found to have toxic levels of lead, cadmium, mercury; cadmium, arsenic, mercury are known carcinogens; mercury also affects the nervous system

- Pesticides beyond permissible limit found in vegetables, fodder, human and bovine milk, as well as blood samples

- 65 per cent blood samples showed DNA mutation; there has been a sharp increase in cancer, neurological disorders, liver and kidney diseases, congenital defects, miscarriages

- This health crisis has been caused by the overuse of pesticides and the dumping of industrial effluents, which have made soil and water toxic

***

Baljeet Kaur of Giana village in Punjab's cotton belt has been battling cancer for the last 10 years. First it was her husband who died of colon cancer, now she has cancer of the oesophagus. Her neighbour Mukhtiar Kaur is being treated for breast cancer. The family had a hand pump at home which provided them water for their daily needs but abandoned it after health officials told them its water was toxic. Now they get raw canal water for drinking and cooking. "Who knows if it is the water which has brought this disease on me?" she says. "All I know is that scores of people in our village are dying of cancer." In neighbouring Jajjal, the word cancer only evokes deja vu. Karnail Singh and his wife Balbir Kaur both have cancer, live in adjoining houses, each with one of their sons. "This village is cursed," says their brother Jarnail Singh.

On death row: Jajjal's Karnail Singh and his wife both have cancer, live in adjoining houses, each with a son

In Ghaunzpur in Ludhiana district, a good 200 km away, Manjit and Gurjit Singh lost both their parents to hepatitis; an uncle is afflicted with the same. The water from the hand pump in the courtyard turns foamy when heated, so they have dug a submersible pump which pumps out water from 300 ft below. Other households in the village cannot afford to do so.

For Punjab's prosperous farming households and lush green fields, the famed Green Revolution is beginning to turn bilious from within. Its gushing tubewells, the cattle heavy with milk, the trolleys laden with vegetables destined for urban markets—all are likely to be contaminated with toxins. The state is sitting on an environmental crisis and few of have any idea of how to tackle it.

Some two years ago, when reports of increased cancer deaths first started coming in from the state's cotton belt, the Chandigarh-based Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER) decided to investigate. A preliminary study it conducted found a much higher prevalence of cancer in the Talwandi Sabo block and the presence of heavy metals and pesticides in drinking water in the area. It recommended a comprehensive study of the status of environmental health in Punjab's other cotton-growing areas, the setting up of a cancer registry in the state, and regular monitoring of the drinking water. Of course, intense pressure from the pesticides lobby ensured none of this came to pass and the report was ignored.

This month, the PGIMER's department of community medicine has submitted a comprehensive epidemiological study (see box) in areas along the state's five major rivulets to the State Pollution Control Board. The results are so shocking that the board has put it under wraps and is having second thoughts about releasing it. Says Dr J.S. Thakur, an assistant professor at PGIMER, who conducted the study, "Our two studies show that all of Punjab is toxic and people do not have safe water to drink. Both agricultural and industrial malpractices are to be blamed for this."

The worst affected is the southeastern Malwa region, better known these days as the 'cancer belt'. To counter increasingly resistant pests, farmers here spray their fields with pesticide doses far above those recommended—often cocktailing two or more chemicals. As the former sarpanch of Jajjal, Najar Singh, told Outlook, "Although the recommended dose is about five sprays per season, we sometimes spray our fields 25 to 30 times. Almost every third day!" Punjab, which makes up for just 2.5 per cent of the country's area, accounts for 18 per cent of the pesticides used in the country.

The state's problem is their unregulated use, say experts, with most farmers unaware of how to use or dispose of the empty pesticide cans. So, in the last four decades pesticides have seeped into the underground water aquifers, as also in the state's water bodies. And in the last 10 years, more and more well-off households along the drains have begun setting up submersible pumps to get water from deep aquifers, as water from taps and handpumps is unfit for human use.

Punjab's finance minister Manpreet Badal is a legislator from Muktsar district's Gidderbaha, located in the cancer belt. "In the 50 villages in my constituency," he says, "there'd be a thousand-odd cancer cases. I've lost count of the funerals of cancer victims I've attended in my area since the beginning of this year. It is an epidemic here." A train leaving from Bhatinda to Bikaner has been dubbed 'cancer express' as most patients from here go to Bikaner's cancer hospital for treatment. Even a child in these parts knows what chemotherapy is about. "Our neighbour used to take hot injections before she died last year," says little Kiranjot at Chandbaja village in Faridkot district. "Many others in our village have taken them."

Giana's Baljeet Kaur has cancer of the oesophagus

Dr G.P.I. Singh, who heads the department of community medicine in Ludhiana's Dayanand Medical College, has recently begun studying, along with other private doctors across the state and NGO Kheti Virasat Mission (KVM), the impact of heavy metals and pesticides on reproductive health in Punjab. "One of the things worrying us," he says, "is that the skewed sex ratio in both Punjab and Haryana could also be due to chemical exposure, as the female foetus is more vulnerable. We notice an increase in spontaneous abortions, infertility, distorted menarche and foetuses with neural tube defects." There is also a high incidence of grey hair among children and young adults in this area. Ask for one, and most villages throw up several.

Not just pesticides, but unchecked effluent flow from industries into the rivers and drains too has contaminated underground water in Punjab. At Ghaunzpur, for instance, five paper mills dump their entire effluent unchecked into the Buddha Nullah. However, the state pollution board which is supposed to check industries such as these from polluting water bodies couldn't be bothered. This is evident from the response of the board's chairman, Yogesh Goel, when queried about the PGIMER report."I'm busy right now. You can ask the secretary of the board about it," he told Outlook. Quite predictably, the secretary too made himself unavailable. KVM director Umendra Dutt, who has been most active in raising the issue of cancer deaths in Punjab, feels that agricultural scientists in cahoots with pesticide manufacturing mncs have led to this health crisis. "All these years agricultural scientists have been advocating heavy doses of pesticides without informing farmers of the damage improper usage causes," he says.

Meanwhile, though officials are aware of the problem, the state is yet to evolve a concrete water policy to address the problem. Says J.R. Kundal, Punjab's secretary for water supply and sanitation, "Ideally, there should be an umbrella task force to deal with the problem in its entirety," he says. "Presently, different agencies are conducting overlapping studies which will take us nowhere. I am heading a task force to study arsenic in water, while the state planning board is looking into drinking water and allied issues. Although 90 per cent of the underground water is used for irrigation and just 10 per cent for drinking water, we realise that this 10 per cent is crucial for the health of our people."

With the government unsure of what to do, Manpreet Badal has installed four distribution points supplying Reverse Osmosis water in his constituency. "Till a statewide water supply scheme comes up," says he, "I've taken this interim measure." His people are lucky. Others in the state are condemned to drinking polluted water and suffer from deadly diseases, reaping the poisoned fruit of a Green Revolution gone unchecked.

Everything in one place… All new Windows Live!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)