'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label public sector. Show all posts

Showing posts with label public sector. Show all posts

Friday, 13 October 2023

Wednesday, 30 August 2017

PFI is bankrupting Britain's public services

The plight of my local hospital trust in Walthamstow shows just how debt is holding our country back. Could this be the time for a windfall tax?

Stella Creasey in The Guardian

Next time you have an appointment cancelled at hospital, or a headteacher tells you their school will be losing staff because of budget cuts, ask how much PFI debt they have – the answer may surprise you. My hospital trust, in north-east London, spends nearly £150m a year repaying its PFI debt – nearly half of which is on interest payments. If Theresa May is serious about taking on the unacceptable face of capitalism, she could save Britain a fortune if she goes after the legal loan sharks of the public sector.

New research from the Centre for Health and the Public Interest (CHPI) shows just how much these debts are hurting our NHS. Over the next five years, almost £1bn of taxpayer funds will go to PFI companies in the form of pre-tax profits. That’s 22% of the extra £4.5bn given to the Department of Health in the 2015 spending review, and money that would otherwise have been available for patient care.

The company that holds the contract for University College London hospital has made pre-tax profits of £190m over the past decade, out of the £725m the NHS has paid out. This alone could have built a whole new hospital as 80% of PFI hospitals cost less than this to construct. This is not just about poor financial control in the NHS – UK PFI debt now stands at over £300bn for projects with an original capital cost of £55bn.

It’s time to grasp the nettle and get Britain a better line of credit

Private finance initiatives are like hire-purchase agreements – superficially a cheap way to buy something, but the costs quickly add up, and before you know it the debt is crippling.

For decades, governments of both main parties have used them for the simple but ultimately short-sighted view that it keeps borrowing off the books – helping reduce the amount of debt the country appears to have, but at great longer-term expense. Its now painfully clear that the intended benefits of private sector skills to help manage projects have been subsumed in the one-sided nature of these contracts, to devastating effect on budgets.

No political party can claim the moral high ground. The Tories conveniently ignore the fact that these contracts started under the John Major government – and are expanding again under Theresa May, with the PF2 scheme. Labour veers between defensive rhetoric that PFI was the best way to fund the investment our public sector so desperately needed during its last government, and angrily demanding such contracts be cancelled outright, wilfully ignoring what damage this would do to any government’s ability to ever borrow again.

It’s time to grasp the nettle and get Britain a better line of credit. That requires both tough action on the existing contracts to protect taxpayers’ interests, and getting a better deal on future borrowing. Some have already bought out contracts – Northumbria council took out a loan to buy out Hexham hospital’s PFI, and in doing so saved £3.5m every year over the remaining 19-year term. But as the National Audit Office has shown, gains from renegotiating individual contracts are likely to be minimal – what is saved in costs is paid out in fees to arrange.

However, the CHPI research also shows up another interesting facet of PFI. Just eight companies own or appear to have equity stakes in 92% of all the PFI companies in the NHS. Renegotiating not the individual deals done for hospitals or schools, but across the portfolios of the companies themselves could realise substantial gains. Innisfree, which manages my local hospital’s PFI and others across the country and has just 25 staff, stands to make £18bn alone over the coming years. If these companies are resistant to consolidating these loans into a more realistic cost, then it’s time to look again at their tax reliefs, or – given the evidence of excessive profits in this industry that shareholders have received – resurrect one of New Labour’s early hits with a windfall tax on the returns made.

Longer term, we need to ensure there is much more competition for the business of the state. Despite interest rates being low for over a decade, these loans have stayed stubbornly expensive. The lack of viable alternatives – whether public borrowing or bonds – gives these companies a captive market. If the government wants better rates, it needs to ensure there are more options to choose between, whether by allowing local authorities to issue bonds, or reforming Treasury rules that penalise public sector borrowing in the first place.

As our public services struggle under the pressure of PFI, Labour must lead this debate to show how we can not only learn from our past, but also provide answers for the future too. The government has already spent £100bn buying the debt of banks through quantitative easing. With Brexit expected not only to add £60bn to our country’s debt but also affect our access to European central bank funds, taking on our expensive creditors is a battle no prime minister can ignore in the fight to stop Britain going bust.

Stella Creasey in The Guardian

Next time you have an appointment cancelled at hospital, or a headteacher tells you their school will be losing staff because of budget cuts, ask how much PFI debt they have – the answer may surprise you. My hospital trust, in north-east London, spends nearly £150m a year repaying its PFI debt – nearly half of which is on interest payments. If Theresa May is serious about taking on the unacceptable face of capitalism, she could save Britain a fortune if she goes after the legal loan sharks of the public sector.

New research from the Centre for Health and the Public Interest (CHPI) shows just how much these debts are hurting our NHS. Over the next five years, almost £1bn of taxpayer funds will go to PFI companies in the form of pre-tax profits. That’s 22% of the extra £4.5bn given to the Department of Health in the 2015 spending review, and money that would otherwise have been available for patient care.

The company that holds the contract for University College London hospital has made pre-tax profits of £190m over the past decade, out of the £725m the NHS has paid out. This alone could have built a whole new hospital as 80% of PFI hospitals cost less than this to construct. This is not just about poor financial control in the NHS – UK PFI debt now stands at over £300bn for projects with an original capital cost of £55bn.

It’s time to grasp the nettle and get Britain a better line of credit

Private finance initiatives are like hire-purchase agreements – superficially a cheap way to buy something, but the costs quickly add up, and before you know it the debt is crippling.

For decades, governments of both main parties have used them for the simple but ultimately short-sighted view that it keeps borrowing off the books – helping reduce the amount of debt the country appears to have, but at great longer-term expense. Its now painfully clear that the intended benefits of private sector skills to help manage projects have been subsumed in the one-sided nature of these contracts, to devastating effect on budgets.

No political party can claim the moral high ground. The Tories conveniently ignore the fact that these contracts started under the John Major government – and are expanding again under Theresa May, with the PF2 scheme. Labour veers between defensive rhetoric that PFI was the best way to fund the investment our public sector so desperately needed during its last government, and angrily demanding such contracts be cancelled outright, wilfully ignoring what damage this would do to any government’s ability to ever borrow again.

It’s time to grasp the nettle and get Britain a better line of credit. That requires both tough action on the existing contracts to protect taxpayers’ interests, and getting a better deal on future borrowing. Some have already bought out contracts – Northumbria council took out a loan to buy out Hexham hospital’s PFI, and in doing so saved £3.5m every year over the remaining 19-year term. But as the National Audit Office has shown, gains from renegotiating individual contracts are likely to be minimal – what is saved in costs is paid out in fees to arrange.

However, the CHPI research also shows up another interesting facet of PFI. Just eight companies own or appear to have equity stakes in 92% of all the PFI companies in the NHS. Renegotiating not the individual deals done for hospitals or schools, but across the portfolios of the companies themselves could realise substantial gains. Innisfree, which manages my local hospital’s PFI and others across the country and has just 25 staff, stands to make £18bn alone over the coming years. If these companies are resistant to consolidating these loans into a more realistic cost, then it’s time to look again at their tax reliefs, or – given the evidence of excessive profits in this industry that shareholders have received – resurrect one of New Labour’s early hits with a windfall tax on the returns made.

Longer term, we need to ensure there is much more competition for the business of the state. Despite interest rates being low for over a decade, these loans have stayed stubbornly expensive. The lack of viable alternatives – whether public borrowing or bonds – gives these companies a captive market. If the government wants better rates, it needs to ensure there are more options to choose between, whether by allowing local authorities to issue bonds, or reforming Treasury rules that penalise public sector borrowing in the first place.

As our public services struggle under the pressure of PFI, Labour must lead this debate to show how we can not only learn from our past, but also provide answers for the future too. The government has already spent £100bn buying the debt of banks through quantitative easing. With Brexit expected not only to add £60bn to our country’s debt but also affect our access to European central bank funds, taking on our expensive creditors is a battle no prime minister can ignore in the fight to stop Britain going bust.

Sunday, 9 February 2014

The public sector isn't perfect but at least it doesn't fleece us

A culture in which the customer comes last will fail and fail again

However friendly people working a call centre are, they are caught in a process that puts the customer last. Photograph: Murdo Macleod for the Observer

Lloyds Bank casually announced last week that it was setting aside another £1.8bn to meet potential claims from customers after knowingly selling them expensive insurance policies they could not need nor use. The grand total of provisions it has made is now nearly £10bn for claims from up to 700,000 people – a stunning indictment of its business practices.

Yet there is little public angst. Last December, Lloyds was fined a record £28m by the Financial Conduct Authority for the period between 1 January 2010 and 31 March 2012 – during which the government held a 39% stake in the bank – for having lax controls and incentivising its staff to treat its customers as milch cows. Extravagant "champagne" bonuses were offered to staff who could loot their customers with policies cynically designed to offer nothing of value, nothing less than organised theft. In Ireland at least, the former executives of the bust Anglo Irish bank are on trial. In Britain, the former head of Lloyds retail banking division, Helen Weir, has gone on to become finance director of John Lewis, but at least she has said how sorry she is. That's all right then.

Otherwise, Lloyds Bank is hardly eating humble pie. While Barclays chief executive, Antony Jenkins, is trying to engineer a massive change in his bank's culture, his counterpart at Lloyds seems to be focused on one target only – ensuring sufficient profitability to allow the government to offload more of its stake and, along the way, to vastly enrich himself. There has been zero pressure from his largest shareholder – the government – to reproduce Jenkins's initiative and do more about the mis-selling scandal than to utter bromides about winning back trust. The solution is for the bank to become 100% owned by the private sector as soon as possible, seen as an unalloyed good thing.

This combination – feckless owners, in this case HM Treasury, which cares nothing about the bank's ethics but only about its share price, alongside managers who appear to see their customers as objects to be fleeced – is deadly. But the media are hardly abuzz with sustained complaint and protest. Rather, they have helped construct the doctrine that anything done in the private sector is generally fabulous, and that £10bn scandals such as Lloyds, while deplorable, are the exception. Meanwhile, anything done in the public sector is by definition abominable, wasteful and ripe for privatisation or contracting out. The sooner Lloyds is in the private sector away from the "dead" hand of state ownership the better. But the state has not been a dead hand: it has been preoccupied with its own financial interests, like every other private owner.

Lloyds is not alone: the other banks have earmarked another £10bn for mis-selling similar products. Their investment bank arms are engulfed with charges of colluding to rig interest rates and foreign exchange markets on a global scale, along with more record-breaking fines. Meanwhile, the average customer's experience remains dismal. Staff in disempowered branches and industrialised call centres do their best to be friendly, but work within processes in which a good customer experience is plainly a low priority. Trying to exercise my right to flex a credit facility recently was a descent into a privatised Orwellian madness, while anyone who has had to look after an elderly relative's financial affairs enters a bureaucratic, time-consuming labyrinth.

This is not a culture confined to banking. Bombardier recently walked away from a £350m contract to provide signalling for London Underground: it had underestimated the technical complexity and would not commit the resource to meet its side of the bargain. But last week it picked up the £1bn contract to build 65 trains for Crossrail, with its disgraceful behaviour over the signalling contract forgotten, threatening to close its Derby plant if it did not get the business.

Then there are Serco and G4S, with their litany of failures as holders of government contracts. The root of their difficulties is, whatever their original virtues, both have built a culture in which exploiting, rather than serving, the customer comes first – whether it's Serco charging the state for electronically tagging prisoners who did not exist or G4S woefully underproviding security guards for the Olympics. The same dynamic – transient, greedy owners and pay systems that over-reward short-term financial success and cutting corners – produces the same result.

Now large parts of the probation service are to be run in the same way by the same kind of company, with the justice secretary, Chris Grayling, absurdly promising more " reform" and "efficiency". He is outdone by his colleague Dan Poulter at health, selling off 80% of Plasma Resources UK, the NHS company that secures blood plasma for British patients, to Bain Capital, the private equity company built by presidential candidate Mitt Romney. Bain's sole interest is financial, constrained only by its fear of a reputational disaster if patients start dying as it cuts costs and over-rewards managers who try to fleece the NHS, as they necessarily will. Who could consign the provision of blood plasma to such custodians? Only a fool, knave or Tory politician.

The NHS takes a daily pummelling, but enter its portals and a very different culture rules. Despite all the efforts of successive New Labour and Conservative ministers intent on reproducing the private sector "disciplines" that so animate Lloyds, Bombardier, Serco, G4S et al, it still manages to combine humanity and efficiency. Its systems are not extravagant, but there is a sense, as I recently discovered with a close family member in a long spell in hospital, that the patient remains at the centre of everyone's preoccupations.

The public sector is imperfect: it is run and operated by fallible human beings. There are spectacular failings, ranging from the BBC's wasted £100m on its digital media initiative to the unfolding IT disaster over universal credit. But what it does not deserve is universal castigation because a priori it must be useless. It is accountable. It does not loot its users. It is pretty efficient. It is humane.

Nor does the private sector warrant such fawning praise or the self-pity of many of its leaders who claim that profit is still a dirty word. It can do magic – the smartphone, anti-cancer drugs, multiple apps, robots – but it cuts corners too. The headlines, as I write, are of a food scandal in which a third of sampled foodstuffs are wrongly labelled. Regulation, derided as a burden on business, is, rather, what society deploys to keep business honest, whether it emanates from London or Brussels. It is time for a reset and a rebalance. End the jihad against all things public and invite business genuinely to earn its profits.

Tuesday, 16 October 2012

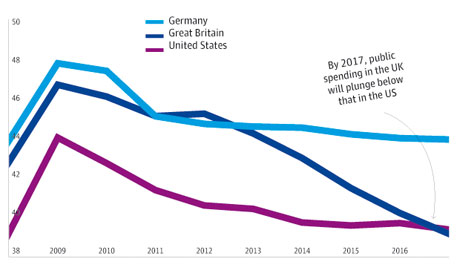

The graph that shows how far David Cameron wants to shrink the state

If the Tories get their way, within five years the UK will have a smaller public sector than any major developed nation

Government spending as a percentage of national GDP. Photograph: IMF WEO Database Oct 2012

This column is normally accompanied by a photo; an illustration that takes its cue from the text. But not today. The chart you see on this page is plainly not decorative: it is the main event. All I'm going to discuss is its implications.

Drawing on IMF figures published last week, the graph compares what will happen to government spending in Britain up to 2017 with the outlook for Germany and the US. And what it shows is that the UK will plunge from public spending on a par with Germany in 2009, to spending less than the US by 2017. Had France, Sweden or Canada been included on this graph, the UK would still come bottom. If George Osborne gets his way, within the next five years, Britain will have a smaller public sector than any other major developed nation.

Fan or critic, nearly everyone now agrees that this government wants to shrink the state, but very few take on board what that means. This graph shows just how radical those ministerial plans are. Particularly striking is the fact that Britain will end up spending less as a proportion of its national income than even the US, the international byword for a decrepit public sector. According to Peter Taylor-Gooby, professor of social policy at Kent, this will be the first time it has happened since at least 1980 and possibly in recorded history. For it to take place within half a decade is a shift so dramatic that few people in frontline politics, let alone among the electorate, have understood its implications.

Forget all that ministerial guff about the necessity of cutting the public sector to spur economic growth. Had that argument been true, British businesses would be in leonine form by now, instead of their current chronic enfeeblement. It was notable at last week's Tory party conference how Osborne and David Cameron didn't even try to argue for the economic benefits of austerity – how could they? – but grimly asserted that there was no alternative.

Forget, too, the argument that only cuts have kept Britain's borrowing costs from rocketing. In the IMF's summer healthcheck for the UK was another chart which showed that the only nations where interest rates had spiralled upwards were those in the eurozone, and those without control of their own currency and monetary policy. Every other major economy, no matter what their debt load, was able to borrow from the financial markets as cheaply as ever.

Strip away the usual economic and financial alibis for such drastic austerity and what you're inevitably left with is a purely political motive: namely, a desire to transform the British state from being recognisably European, with continental levels of public spending, to something sub-American in its miserliness.

Let me make two caveats. First, there was no way Britain was going to maintain public spending at 2009 levels. That year, the Labour government threw the kitchen sink at the economy, after which you would expect some belt-tightening. Still, as Carl Emmerson of the Institute for Fiscal Studies points out, after both world wars, the level of public spending in Britain rose permanently; you might expect something similar after a once-in-a-lifetime financial crisis. Given how fast Britain is ageing, and how much we will need to spend on pensions and care for the elderly, there is no reason why the state in Britain should shrink back to some magic level of 40% of the economy.

Second, this chart is based on current US budget plans: if Mitt Romney moves into the White House next January, or even if Barack Obama is re-elected and has to strike a bargain with intransigent Republicans, then Washington is also likely to make stringent cuts. But that last qualification only reinforces the larger argument. Whether in Britain or the US, the right are trying to whip the rest of us into a giant race to the bottom, where public services, welfare entitlements and employment rights are all to be tossed overboard.

Cameron admitted as much in last Wednesday's conference speech. Lumping together Nigeria with China and India and Brazil, he described them as "the countries on the rise … lean, fit, obsessed with enterprise, spending money on the future – on education, incredible infrastructure and technology". As anyone who has ever tried to keep a car on the potholed roads of Bihar, in northern India, will know, that description is a giant porky. But Cameron wanted to draw a comparison with "the countries on the slide … fat, sclerotic, over-regulated, spending money on unaffordable welfare systems, huge pension bills, unreformed public services".

From compassionate Conservative to growth rainmaker to state-shrinker, Cameron has gone through a huge change since 2005. But that is nothing like what lies ahead for the rest of Britain in the next five years. Prepare yourself for welfare to be downsized into American-style workfare, for public-sector jobs to be turned into a second-class employment and for services, from school to healthcare, to demand that users pay more to get something decent. The future is American.

Monday, 12 March 2012

In praise of Public Sector Banks

Black sheep of

finance

By Ellen Brown in Asia Times Online

The common perception is that government bureaucrats are bad businessmen. To determine whether government-owned banks are assets or liabilities, then, we need to look farther afield.

When we remove our myopic US blinders, it turns out that globally, not only are publicly owned banks quite common but that countries with strong public banking sectors generally have strong, stable economies.

According to an Inter-American Development Bank paper presented in 2005, the percentage of state ownership in the banking industry globally by the mid-nineties was over 40%. [2] The BRIC countries - Brazil, Russia, India, and China - contain nearly three billion of the world’s seven billion people, or 40% of the global population. The BRICs all make heavy use of public sector banks, which compose about 75% of the banks in India, 69% or more in China, 45% in Brazil, and 60% in Russia.

The BRICs have been the main locus of world economic growth in the last decade. China Daily reports, "Between 2000 and 2010, BRIC's GDP grew by an incredible 92.7%, compared to a global GDP growth of just 32%, with industrialized economies having a very modest 15.5%."

All the leading banks in the BRIC half of the globe are state-owned. [3] In fact the largest banks globally are state-owned, including:

By Ellen Brown in Asia Times Online

Once the black sheep of high finance, government owned banks can reassure depositors about the safety of their savings and can help maintain a focus on productive investment in a world in which effective financial regulation remains more of an aspiration than a reality. - Centre for Economic Policy Research, VoxEU.org (January 2010). [1]Public sector banking is a concept that is relatively unknown in the United States. Only one state - North Dakota - owns its own bank. North Dakota is also the only state to escape the credit crisis of 2008, sporting a budget surplus every year since; but skeptics write this off to coincidence or other factors.

The common perception is that government bureaucrats are bad businessmen. To determine whether government-owned banks are assets or liabilities, then, we need to look farther afield.

When we remove our myopic US blinders, it turns out that globally, not only are publicly owned banks quite common but that countries with strong public banking sectors generally have strong, stable economies.

According to an Inter-American Development Bank paper presented in 2005, the percentage of state ownership in the banking industry globally by the mid-nineties was over 40%. [2] The BRIC countries - Brazil, Russia, India, and China - contain nearly three billion of the world’s seven billion people, or 40% of the global population. The BRICs all make heavy use of public sector banks, which compose about 75% of the banks in India, 69% or more in China, 45% in Brazil, and 60% in Russia.

The BRICs have been the main locus of world economic growth in the last decade. China Daily reports, "Between 2000 and 2010, BRIC's GDP grew by an incredible 92.7%, compared to a global GDP growth of just 32%, with industrialized economies having a very modest 15.5%."

All the leading banks in the BRIC half of the globe are state-owned. [3] In fact the largest banks globally are state-owned, including:

|

A May 2010 article in The Economist noted that the strong and stable publicly owned banks of India, China and Brazil helped those countries weather the banking crisis afflicting most of the rest of the world in the last few years. [5] According to Professor Kurt von Mettenheim of the Sao Paulo Business School of Brazil: Government banks provided counter cyclical credit and policy options to counter the effects of the recent financial crisis, while realizing competitive advantage over private and foreign banks. Greater client confidence and official deposits reinforced liability base and lending capacity. The credit policies of BRIC government banks help explain why these countries experienced shorter and milder economic downturns during 2007-2008. [6]Surprising findings In a 2010 research paper summarized on VoxEU.org, economists Svetlana Andrianova, et al, wrote that the post-2008 nationalization of a number of very large banks, including the Royal Bank of Scotland, "offers an opportune moment to reduce the political power of bankers and to carry out much needed financial reforms." [7] But "there are concerns that governments may be unable to run nationalized banks efficiently." Not to worry, say the authors: Follow-on research we have carried out (Andrianova et al, 2009) ... shows that government ownership of banks has, if anything, been robustly associated with higher long run growth rates.Expanding on this theme in their research paper, the authors write: While many countries in continental Europe, including Germany and France, have had a fair amount of experience with government-owned banks, the UK and the USA have found themselves in unfamiliar territory.But that is not what the data of these researchers showed: [W]e have found that ... countries with government-owned banks have, on average, grown faster than countries with no or little government ownership of banks. ... This is, of course, a surprising result, especially in light of the widespread belief - typically supported by anecdotal evidence - that " ... bureaucrats are generally bad bankers" ...What accounts for their surprising findings? The authors provide a novel explanation: We suggest that politicians may actually prefer banks not to be in the public sector. ... Conditions of weak corporate governance in banks provide fertile ground for quick enrichment for both bankers and politicians - at the expense ultimately of the taxpayer. In such circumstances politicians can offer bankers a system of weak regulation in exchange for party political contributions, positions on the boards of banks or lucrative consultancies.The BRICs as a global power Focusing on the financing of real businesses and economic growth seems to be the secret of the BRICs, which are leading the world in economic development today. But the BRIC phenomenon is more than just a growth trend identified by an economist. It is now an international organization, an alliance of countries representing the common interests and goals of its members. The first BRIC meeting, held in 2008, was called a triumph for Russian leader Vladimir Putin's policy of promoting multilateral arrangements that would challenge the United States' concept of a unipolar world. [8] The BRIC countries had their first official summit and became a formal organization in Yekaterinburg, Russia, in 2009. They met in Brazil in 2010 and in China in 2011, and they will meet in India in 2012. In 2010, at China's invitation, South Africa joined the group, making it "BRICS" and adding a strategic presence on the African continent. The BRICS seek more voice in the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank. They are even discussing their own multicultural bank to fund projects within their own nations, in direct competition with the IMF. They oppose the dollar as global reserve currency. After the Yekaterinburg summit, they called for a new global reserve currency, one that was diversified, stable and predictable; and they have the clout to get it. [9] According to Liam Halligan, writing in The UK's Telegraph: The BRICs account for ... around three-quarters of total currency reserves. They have few serious fiscal issues and all are net external creditors. [10]Western financial interests have long fought to maintain the dollar as global reserve currency, but they are losing that battle, despite economic and military coercion. Russia, China and India are now nuclear powers. The BRICS will have to be negotiated with, and the first step to forming a working relationship is to understand how their economies work. |

Wednesday, 7 December 2011

The true costs of Keynes

By Martin Hutchinson

Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong each killed tens of millions of people, and John Maynard Keynes was a pacifist who never fired a shot in anger. However, economically, when the billions come to be totted up, it may well be the case that Keynes was the most destructive of the four.

He cannot entirely be blamed for mistakes in monetary policy, which he never understood, and even his "stimulus" ideas owed much to those who came before him - for example Arthur Pigou - and after him - for example Joan Robinson. Yet the other value destroyers had their henchmen too, in Heinrich Himmler, Lavrenti Beria and Jiang Qing. Overall, when henchmen are added in, Keynes runs the other value destroyers close, and may in the future surpass them as his value-destructions continue. Truly, persuasive but misguided economic theories can be much more damaging than they appear.

This is not to claim that big government per se is value-destructive (it is, but that's a separate issue.) The right size of government is a matter for legitimate debate, and successful societies such as Sweden and Singapore can be built with very different sizes of government. Personally, I would rather live in Singapore than Sweden, and I would expect Singapore to exhibit markedly faster long-term economic growth than Sweden, but both societies run their finances in a responsible manner and are models of governmental integrity.

Since both Sweden and Singapore currently have modest budget surpluses and have kept control of their currencies and avoided excessive monetary stimulus, they are in the modern debased sense of the term non-Keynesian, even if the managers of Sweden's economy might well describe themselves as Keynesians for the sake of harmony at international gatherings.

The Keynesian fallacy is in essence one of getting something for nothing. By Keynesian fiscal stimulus, normally involving spending more money though occasionally through tax cuts, providing they avoid the annoyingly savings-prone rich, we are supposed to produce additional economic output whenever there is an "output gap" from full employment, that is, in all conditions save those of a raging boom, when resources are scarce.

Keynes himself recommended such stimulus only at the bottom of deep recessions, and suggested that it should be balanced by running budget surpluses in times of boom. Needless to say, his disciples have neglected the disciplines he recommended.

Similarly, the analogous monetary policy (which Keynes personally did not advocate, since he believed that interest rates had no effect on output) pushes down interest rates and indulges in ever-more lavish bouts of monetary "stimulus" in the belief that by doing so the economy can be persuaded to expand more rapidly.

It's fair to claim that monetary stimulus does not derive directly from Keynes (though it is not new - it was a policy advocated by Keynesians in the 1960s Lyndon B Johnson administration, for example.) However fiscal stimulus is a direct product of Keynes' 1936 General Theory and both forms of stimulus derive from Keynes' overall approach of flouting economic orthodoxy and using ingenious paradox to propound unorthodox policies.

Keynes was the origin of the "stimulus" approach; its central idea that by manipulating monetary or fiscal policy we can get a bigger government than we pay for is his. It is thus fair to blame the costs of that approach on him.

Those costs are considerable. In the 1930s, US president Herbert Hoover's reckless expansion of government spending, including loans to cronies through the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, caused further slowdown in the economy, which was exacerbated by his dreadful early 1932 increase in the top marginal rate of tax from 25% to 63%.

Then, as I discussed a few weeks ago, Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal deficit spending, combined with his reckless "set the gold price in my pyjamas" monetary policy prolonged the Great Depression far longer than would naturally have occurred, delaying full recovery from 1934-35 to 1939-40.

In the recent unpleasantness, fiscal stimulus worldwide initially appeared merely ineffective. By diverting resources from the productive private sector to unproductive public sector boondoggles it reduced long-term output. In the US case, the Barack Obama stimulus converted a vigorous recovery into an anemic one; only in the third quarter of 2011, after the effects of stimulus had begun to wear off, did output begin to accelerate and unemployment trend down (in this case we should celebrate public sector job losses and declines in public sector output, since they free up resources for healthy private sector growth!).

However, with the euro crisis it has become clear that fiscal stimulus, if excessive, has an exponentially adverse effect. By increasing deficits to unsustainable levels, it precipitates bond market fears about the state's credit risk. Naturally, that strangles credit availability to almost all entities domiciled in the country concerned.

Thus while a mild fiscal stimulus in a country that before recession was running a surplus might be mildly beneficial (because the differential between private sector savings rates and the 100% stimulus spending rate outweighed the inefficiency effect of diverting resources to the public sector), a large fiscal stimulus, or one incurred in a country like Greece or the 2009 US that was already dangerously in deficit, will cause economic damage rising to many times the value of the stimulus itself, persisting for years or even decades to come.

Monetary stimulus is similarly damaging. As Walter Bagehot remarked over a century ago, the correct response to financial crisis is to lend on top quality security at very high interest rates. This was notably not done in 2008; instead the injection of liquidity to favored companies was accompanied by pushing interest rates far below inflation. Repeating the monetary stimulus in 2010 and again in 2011, when in the United States at least the financial crisis was over, was inexcusable.

Monetary stimulus causes structural damage to the economy in the following ways:

|

As recent events have overwhelmingly demonstrated, both fiscal and monetary stimulus are highly addictive, since they appear to provide something for nothing and the cost of reversing them appears unpleasant to the Keynesians who control the levers of policy. As to their cost, the current Congressional Budget Office projections suggest that there is at present a 5% output gap below full employment, and that the output gap will disappear only in 2016. The cost of current Keynesian policies over 2009-16 can thus be conservatively estimated at about 15% of GDP, or $2.2 trillion in today's dollars. To that we can add very roughly 50% of one year's 1929 GDP, for the output lost through Keynesian policies in 1932-40, or another $500 billion, for a very conservative total of $2.7 trillion all-told in the United States alone. That may not sound sufficient to counterbalance the tyrants' depredations, but consider: 1930s Germany, 1940s Russia and 1950s China were all much poorer countries than the modern United States. Very roughly, Germany's 1936 GDP and the Soviet Union's 1940 GDP were both about $500 billion modern dollars, while China's 1955 GDP was about $1,500 billion. Thus Hitler and Stalin could have destroyed their entire output for more than five years, and Mao for almost two years, before doing as much economic damage as Maynard Keynes has wreaked in one country. It's a rough calculation, but illuminating - and while Hitler, Stalin and Mao are long gone, Keynes' depredations continue. Martin Hutchinson is the author of Great Conservatives (Academica Press, 2005) - details can be found on the website www.greatconservatives.com - and co-author with Professor Kevin Dowd of Alchemists of Loss (Wiley, 2010). Both are now available on Amazon.com, Great Conservatives only in a Kindle edition, Alchemists of Loss in both Kindle and print editions. |

Monday, 4 July 2011

How to prepare a Public sector firm for Privatisation - the Air India story

Air India, India’s national carrier-turned-cadaver, is waiting for its last rites. When last heard of, the airline had turned in a loss of Rs 7,000 crore in 2010-11, and was investing in an oversized hat to hit the government for yet another bailout masquerading as a turnaround package.

Only, the amounts this time are too staggering for Pranab Mukherjee to agree to without a fight. According to a report in The Times of India, the airline will need equity support of Rs 43,255 crore just to stay afloat over the next 10 years. Mukherjee is hoping to raise that kind of money by selling public sector equity this year. If he agrees to bail out Air India, it’s as good as kissing goodbye to this moolah.

With liabilities of over Rs 47,000 crore, the airline is on the verge of defaulting on its loans. Mukherjee will thus have to chip in with some money willy-nilly – even if he is not asked for the full sum that SBI Caps has suggested as part of its revival plan for the airline. The newspaper says Air India will require Rs 8,372 crore this year itself – Rs 6,600 crore to pay its bills for 2011-12 and Rs 1,772 crore to keep up with loan payments.

But for all this, the airline still won’t be able to make a profit till 2017-18. Air India, it seems, has been fixed – and fixed for good – by former Civil Aviation Minister Praful Patel, who has often been accused by the unions of batting for Air India’s rivals till the ministry was prised away from his grip last January.

When Patel took over as Minister of State for Civil Aviation in 2004, the domestic carrier (then Indian Airlines) was market leader with a 42% share, but slipping. Today, it is No 5 – behind Jet, Kingfisher, IndiGo and SpiceJet – fighting extinction.

Here’s how Praful Patel did it – ruin Air India that is – and there’s nothing his successor Vayalar Ravi can do to rescue it.

First, load it with debt so high that it can never raise its head again. It is now clear the Air India’s financial problems began in 2004 when Praful Patel chaired a meeting of the board in which the airline suddenly inflated its order for new aircraft from 28 to 68 without a revenue plan or even a route-map for deploying the aircraft, says an India Today report.

An airline with revenues of Rs 7,000 crore was being asked to take on a debt of Rs 50,000 crore. Today, it’s losses themselves are Rs 7,000 crore. And the bailout it is seeking is as big as the cost of those 68 aircraft. The government might as well have gifted those birds to Air India.

Second, Patel presented a merger of Air India with Indian Airlines as the panacea for all ills. It is surprising how often ministers suggest mergers when public sector companies head for ruin. When telecom company MTNL was sliding, then Communications Minister Dayanidhi Maran was suggesting a merger with Bharat Sanchar Nigam Ltd. That didn’t happen, but both MTNL and BSNL are in the sick bay anyway. Praful Patel used the losses of Air India and Indian Airlines to push for their merger, claiming there would be cost savings from synergies. Worldwide, mergers usually destroy value. The Air India-IA merger has been the biggest man-made disaster in aviation history – thanks to their varying cultures and employee costs.

Says Gustav Baldauf, former COO of Air India who fell foul of Patel’s successor and had to quit: “The management never resolved the pending human resource (HR) issues related to the merger. I had warned the Chairman-cum-Managing Director and the Aviation Ministry of the consequences of introducing a single code without resolving issues first. But they never listened,” he told Mid-Day.

Third, Patel seemed to be batting for Air India’s rivals. He handed over lucrative routes to private players. Though Air India had no birthright to every lucrative route, Patel’s overnight manoeuvres in this regard suggested that he had a clear conflict of interest by being both Aviation Minister and board member in Air India.

A Tehelka report quotes Capt Mohan Ranganathan, an aviation expert, as saying that the airline handed over “flying rights on lucrative sectors in the Gulf to foreign airlines, including Etihad Airways, Qatar Airways, Air Asia, Singapore Airlines and several others…” One glaring instance of a sudden handover could not have come without Patel’s nod. Tehelka says that in October 2009, the airline sent “letters…to its stations in Kozhikode, Doha and Bahrain stating that it was withdrawing operations on the route” – a route in which the airline was making money hand over fist. Very soon, Jet and Etihad stepped in to fill the gaps, and so did Emirates.

Fourth, Praful Patel’s own airline preferences made it clear who he favoured. According to replies received under the Right to Information Act by one Jagjit Singh, Patel used mostly private airlines. Between June 1, 2009 and July 2, 2010, 26 of the 41 flights he took between Delhi and Mumbai were with Kingfisher. “It is intriguing that the minister who stresses the need for revival of the national carrier himself chooses to ignore it,” said Singh. And this happened just when the Finance Ministry was asking all government employees to use Air India for their official travel to help revive the carrier.

Patel’s haughty reply when asked about this preference of private airlines: “I am the Union Civil Aviation Minister and not the minister in charge for Air India. As a minister, it is not binding upon me to fly only one particular airline. I fly according to my convenience.” But when he ordered so many places for Air India, was he acting as Minister or superboss of the airline?

Fifth, Patel used his clout with Air India often for personal ends. Another RTI query showed that Patel’s kin used the Air India Managing Director’s office to regularly upgrade from economy to business class. Business class is a cost Patel’s family, which is rolling in wealth, can easily afford. So what does this say about Patel’s attitude to the airline?

But is the new Civil Aviation Minister going to reverse the rot set off by Patel?

According to a Financial Express report, the new turnaround plan does not look any more viable than the deadweight Patel cast on Air India by getting it to buy planes it could not afford. The newspaper quotes a Deloitte review of the SBI Caps revival plan which says it’s simply not viable.

Reason: Air India again wants to buy too many aircraft, just like Patel did. “Aviation consultancy Simat Helliesen & Eichner, which carried out a detailed route planning and capacity exercise, has suggested 87 narrow-body aircraft for Air India by 2015, but the carrier has proposed 143, according to Deloitte’s report dated February 11, 2011,” says the newspaper.

Deloitte’s comment: “The only justification that one can have for going in for such capacity expansion can, therefore, be the adoption of a strategy of buying market share through deploying high capacity into the market (with corresponding lower yields and consequent financial implications).”

This means Air India is planning to sink further into losses for years to come.

Over to you, Mr Ravi. Do you want to go down the same path Praful Patel pushed Air India?

The government’s best bet now is to cut its losses. Air India should be privatised or closed down.

Only, the amounts this time are too staggering for Pranab Mukherjee to agree to without a fight. According to a report in The Times of India, the airline will need equity support of Rs 43,255 crore just to stay afloat over the next 10 years. Mukherjee is hoping to raise that kind of money by selling public sector equity this year. If he agrees to bail out Air India, it’s as good as kissing goodbye to this moolah.

With liabilities of over Rs 47,000 crore, the airline is on the verge of defaulting on its loans. Mukherjee will thus have to chip in with some money willy-nilly – even if he is not asked for the full sum that SBI Caps has suggested as part of its revival plan for the airline. The newspaper says Air India will require Rs 8,372 crore this year itself – Rs 6,600 crore to pay its bills for 2011-12 and Rs 1,772 crore to keep up with loan payments.

But for all this, the airline still won’t be able to make a profit till 2017-18. Air India, it seems, has been fixed – and fixed for good – by former Civil Aviation Minister Praful Patel, who has often been accused by the unions of batting for Air India’s rivals till the ministry was prised away from his grip last January.

When Patel took over as Minister of State for Civil Aviation in 2004, the domestic carrier (then Indian Airlines) was market leader with a 42% share, but slipping. Today, it is No 5 – behind Jet, Kingfisher, IndiGo and SpiceJet – fighting extinction.

Here’s how Praful Patel did it – ruin Air India that is – and there’s nothing his successor Vayalar Ravi can do to rescue it.

First, load it with debt so high that it can never raise its head again. It is now clear the Air India’s financial problems began in 2004 when Praful Patel chaired a meeting of the board in which the airline suddenly inflated its order for new aircraft from 28 to 68 without a revenue plan or even a route-map for deploying the aircraft, says an India Today report.

An airline with revenues of Rs 7,000 crore was being asked to take on a debt of Rs 50,000 crore. Today, it’s losses themselves are Rs 7,000 crore. And the bailout it is seeking is as big as the cost of those 68 aircraft. The government might as well have gifted those birds to Air India.

Second, Patel presented a merger of Air India with Indian Airlines as the panacea for all ills. It is surprising how often ministers suggest mergers when public sector companies head for ruin. When telecom company MTNL was sliding, then Communications Minister Dayanidhi Maran was suggesting a merger with Bharat Sanchar Nigam Ltd. That didn’t happen, but both MTNL and BSNL are in the sick bay anyway. Praful Patel used the losses of Air India and Indian Airlines to push for their merger, claiming there would be cost savings from synergies. Worldwide, mergers usually destroy value. The Air India-IA merger has been the biggest man-made disaster in aviation history – thanks to their varying cultures and employee costs.

Says Gustav Baldauf, former COO of Air India who fell foul of Patel’s successor and had to quit: “The management never resolved the pending human resource (HR) issues related to the merger. I had warned the Chairman-cum-Managing Director and the Aviation Ministry of the consequences of introducing a single code without resolving issues first. But they never listened,” he told Mid-Day.

Third, Patel seemed to be batting for Air India’s rivals. He handed over lucrative routes to private players. Though Air India had no birthright to every lucrative route, Patel’s overnight manoeuvres in this regard suggested that he had a clear conflict of interest by being both Aviation Minister and board member in Air India.

A Tehelka report quotes Capt Mohan Ranganathan, an aviation expert, as saying that the airline handed over “flying rights on lucrative sectors in the Gulf to foreign airlines, including Etihad Airways, Qatar Airways, Air Asia, Singapore Airlines and several others…” One glaring instance of a sudden handover could not have come without Patel’s nod. Tehelka says that in October 2009, the airline sent “letters…to its stations in Kozhikode, Doha and Bahrain stating that it was withdrawing operations on the route” – a route in which the airline was making money hand over fist. Very soon, Jet and Etihad stepped in to fill the gaps, and so did Emirates.

Fourth, Praful Patel’s own airline preferences made it clear who he favoured. According to replies received under the Right to Information Act by one Jagjit Singh, Patel used mostly private airlines. Between June 1, 2009 and July 2, 2010, 26 of the 41 flights he took between Delhi and Mumbai were with Kingfisher. “It is intriguing that the minister who stresses the need for revival of the national carrier himself chooses to ignore it,” said Singh. And this happened just when the Finance Ministry was asking all government employees to use Air India for their official travel to help revive the carrier.

Patel’s haughty reply when asked about this preference of private airlines: “I am the Union Civil Aviation Minister and not the minister in charge for Air India. As a minister, it is not binding upon me to fly only one particular airline. I fly according to my convenience.” But when he ordered so many places for Air India, was he acting as Minister or superboss of the airline?

Fifth, Patel used his clout with Air India often for personal ends. Another RTI query showed that Patel’s kin used the Air India Managing Director’s office to regularly upgrade from economy to business class. Business class is a cost Patel’s family, which is rolling in wealth, can easily afford. So what does this say about Patel’s attitude to the airline?

But is the new Civil Aviation Minister going to reverse the rot set off by Patel?

According to a Financial Express report, the new turnaround plan does not look any more viable than the deadweight Patel cast on Air India by getting it to buy planes it could not afford. The newspaper quotes a Deloitte review of the SBI Caps revival plan which says it’s simply not viable.

Reason: Air India again wants to buy too many aircraft, just like Patel did. “Aviation consultancy Simat Helliesen & Eichner, which carried out a detailed route planning and capacity exercise, has suggested 87 narrow-body aircraft for Air India by 2015, but the carrier has proposed 143, according to Deloitte’s report dated February 11, 2011,” says the newspaper.

Deloitte’s comment: “The only justification that one can have for going in for such capacity expansion can, therefore, be the adoption of a strategy of buying market share through deploying high capacity into the market (with corresponding lower yields and consequent financial implications).”

This means Air India is planning to sink further into losses for years to come.

Over to you, Mr Ravi. Do you want to go down the same path Praful Patel pushed Air India?

The government’s best bet now is to cut its losses. Air India should be privatised or closed down.

Wednesday, 22 June 2011

Interesting Stories of the Day

After the UK MPs were caught with their hands in the till, watch out for Euro MPs expenses scandal:

The UK Government has made it appear that all those who receive public sector pensions are the richest folks in the land:

After bombing Libya for so many days now the Arab League chief admits that the plan has not worked and may even be dysfunctional

George Osborne refuses to tell UK citizens how much the Libyan bombings will cost in an age of austerity.

The coalition hopes that the public sector strikes can be used to blame them for preventing the non existent economic recovery

Large yoga class takes place in Times Square, New York, USA.

Half of Britons have German blood.

The UK Government has made it appear that all those who receive public sector pensions are the richest folks in the land:

After bombing Libya for so many days now the Arab League chief admits that the plan has not worked and may even be dysfunctional

George Osborne refuses to tell UK citizens how much the Libyan bombings will cost in an age of austerity.

The coalition hopes that the public sector strikes can be used to blame them for preventing the non existent economic recovery

Large yoga class takes place in Times Square, New York, USA.

Half of Britons have German blood.

Friday, 3 July 2009

Privatisation has been a train wreck

With National Express abandoning a franchise, the system is bankrupt. Railway nationalisation is the only rational solution.

guardian.co.uk, Thursday 2 July 2009 18.30 BST

The temporary nationalisation of the east coast mainline service should be another nail in the coffin of the privatisation of the railways. It shows once again what a bad deal for taxpayers the privatisation of the railways has turned out to be.

The government says it plans to return the franchise as quickly as possible to a private contractor, but it should instead take the opportunity to retain the line in public hands. Following, as it does, the fiasco of Railtrack, which brought the national rail network to the brink of collapse in 2002, and the collapse of Metronet, in charge of two thirds of the misguided public private partnership (PPP) on the tube, this is the right time to plan returning the entire national rail network to public ownership. If the government tossed aside the ideological blinkers of the Treasury and got that message, they would do themselves a great deal of good among passengers and taxpayers alike.

It is a complete con for the National Express group to walk away from the contract, leaving a gap in the national rail budget, forcing the state to bear the cost while the service is re-franchised – possibly at a lower value than the National Express contract – but insisting on its right to continue to operate other franchises unscathed. National Express says it has received "clear and detailed" legal advice that it does not have to hand back its London to Essex franchise and East Anglia routes. So it wants to run away from a problem on one line and let the rest of us pick up the pieces, while continuing to make profits from other lines.

The attempt of National Express to avoid any consequences for their other franchises from their abandonment of the east coast service is just another example of the privateers trying to take the public sector for a ride. As Lord Adonis says, "It is simply unacceptable to reap the benefits of contracts when times are good, only to walk away from them when times become more challenging."

Time and again, we have seen the nationalisation of losses and the privatisation of profits. It's also the latest demonstration that it is a fairy tale that privatisation means the private sector takes the risk as well as taking its profit. In truth, every time a privatisation of a vital public service fails, the public sector picks up the tab. This culture of parts of the private sector fleecing the taxpayer has to stop.

Part of the problem is that civil servants are taken to the cleaners in the construction of the privatisation contracts by the private companies' sharper legal teams. One of the rationales for the tube's PPP was that it made no sense to hand billions of pounds of public money for tube upgrades over to London Underground management and civil servants who had such a poor record of delivering. Yet, these same civil servants were left to draw up the detail of the PPP contracts. They were completely turned over by the private sector.

But the real issue is that it is inherently wasteful to run these services on privatised lines. The nature of the privatising companies is that a significant proportion of the profits of their activities have to be paid in dividends to shareholders rather than reinvested in the service. This is money wasted. A publicly-owned company would be obliged to reinvest any revenues back into the transport system.

Furthermore, privatisation is justified on the grounds that the private sector is driven, through the rigour of competition, to be more efficient and more responsive to passengers' needs. This is a fiction in the case of a natural monopoly like a railway. Apart from the brief period of competition among bidders for contracts, there is no day-to-day competition at all – no one is going to build a rival railway line and poach passengers from the private franchisee. They are under no pressure from any competition at all. In such circumstances, it is more rational, and makes more sense in terms of sustaining investment, for rail services to be publicly-owned.

Nor is it the case that public ownership of the rail network naturally has to involve poorer management than the private sector.

There are many publicly-owned rail companies all over the world that provide services that British transport users can only envy. The task is to build up good quality management, including the best management from around the world, overseeing real investment that meets the needs of rail travellers.

It shouldn't just be the east coast service that's nationalised and it shouldn't just be temporary. Ultimately, the rail network would

be more rationally run in the public sector.

The government says it plans to return the franchise as quickly as possible to a private contractor, but it should instead take the opportunity to retain the line in public hands. Following, as it does, the fiasco of Railtrack, which brought the national rail network to the brink of collapse in 2002, and the collapse of Metronet, in charge of two thirds of the misguided public private partnership (PPP) on the tube, this is the right time to plan returning the entire national rail network to public ownership. If the government tossed aside the ideological blinkers of the Treasury and got that message, they would do themselves a great deal of good among passengers and taxpayers alike.

It is a complete con for the National Express group to walk away from the contract, leaving a gap in the national rail budget, forcing the state to bear the cost while the service is re-franchised – possibly at a lower value than the National Express contract – but insisting on its right to continue to operate other franchises unscathed. National Express says it has received "clear and detailed" legal advice that it does not have to hand back its London to Essex franchise and East Anglia routes. So it wants to run away from a problem on one line and let the rest of us pick up the pieces, while continuing to make profits from other lines.

The attempt of National Express to avoid any consequences for their other franchises from their abandonment of the east coast service is just another example of the privateers trying to take the public sector for a ride. As Lord Adonis says, "It is simply unacceptable to reap the benefits of contracts when times are good, only to walk away from them when times become more challenging."

Time and again, we have seen the nationalisation of losses and the privatisation of profits. It's also the latest demonstration that it is a fairy tale that privatisation means the private sector takes the risk as well as taking its profit. In truth, every time a privatisation of a vital public service fails, the public sector picks up the tab. This culture of parts of the private sector fleecing the taxpayer has to stop.

Part of the problem is that civil servants are taken to the cleaners in the construction of the privatisation contracts by the private companies' sharper legal teams. One of the rationales for the tube's PPP was that it made no sense to hand billions of pounds of public money for tube upgrades over to London Underground management and civil servants who had such a poor record of delivering. Yet, these same civil servants were left to draw up the detail of the PPP contracts. They were completely turned over by the private sector.

But the real issue is that it is inherently wasteful to run these services on privatised lines. The nature of the privatising companies is that a significant proportion of the profits of their activities have to be paid in dividends to shareholders rather than reinvested in the service. This is money wasted. A publicly-owned company would be obliged to reinvest any revenues back into the transport system.

Furthermore, privatisation is justified on the grounds that the private sector is driven, through the rigour of competition, to be more efficient and more responsive to passengers' needs. This is a fiction in the case of a natural monopoly like a railway. Apart from the brief period of competition among bidders for contracts, there is no day-to-day competition at all – no one is going to build a rival railway line and poach passengers from the private franchisee. They are under no pressure from any competition at all. In such circumstances, it is more rational, and makes more sense in terms of sustaining investment, for rail services to be publicly-owned.

Nor is it the case that public ownership of the rail network naturally has to involve poorer management than the private sector.

There are many publicly-owned rail companies all over the world that provide services that British transport users can only envy. The task is to build up good quality management, including the best management from around the world, overseeing real investment that meets the needs of rail travellers.

It shouldn't just be the east coast service that's nationalised and it shouldn't just be temporary. Ultimately, the rail network would

be more rationally run in the public sector.

Upgrade to Internet Explorer 8 Optimised for MSN. Download Now

Wednesday, 12 March 2008

PSBR or PSNCR

PSNCR - Explanation

The PSNCR - public sector net cash requirement - used to be called the PSBR - the public sector borrowing requirement. They are the same thing. They measure the amount the government has to borrow to meet all its expenditure commitments. Governments frequently spend more than they are earning in tax revenue, and so have to borrow to plug the gap.

There are two ways to measure the value of the PSNCR. The first is to look at the PSNCR as an amount of money - usually in billions of pounds (£bn). This is useful as a measure, but we may also want to consider how significant this figure is in the overall context of the economy. £5bn sounds a lot of money (and we would all like a share of it !), but in terms of the overall level of GDP it is fairly insignificant. So the other way to measure the PSNCR is as a percentage of GDP.

The PSNCR tends to vary with the trade cycle. This happens because as the level of growth changes the governments expenditure and tax revenue will also change automatically. For example, imagine the economy is going into recession. As people lose their jobs, incomes fall and this means less income tax. They will also spend less which means the government gets less from VAT and other indirect taxes. At the same time they will need to be paid benefits, and this means an increase in government expenditure. The overall effect of the recession therefore has been to increase the PSNCR.

PSNCR and the Trade Cycle - Why does it vary?

The PSNCR tends to change along with the state of the economy. When things are going well and the economy is booming, the PSNCR will tend to be falling (unless the government is going mad spending on other things!). This is because a booming economy means low unemployment and low unemployment means less spending on benefits. Not only that, but when people are employed they will spend more, and this will boost VAT and other indirect tax receipts.

The impact of a recession on the PSNCR will be the opposite. Increasing unemployment means more spending on benefits, increasing the level of government expenditure. Unemployed people don't pay income tax, and others may find their incomes falling. The combination of these two effects means that the government receives less income tax. Spending also will fall as people have less money and are more reluctant to spend what they do have because of uncertainty about the future. As spending falls so does the government's revenue from indirect taxes. As if all this weren't enough of a problem, the performance of firms will also affect the government's finances. In times of recession, firms' profits will fall, in fact they may even make losses. Since corporation tax

is paid on profits, the governments tax revenues will be hit even further.

So boom periods should help to lower the PSNCR, while recessions and economic slowdown will tend to push it back up again.

PSNCR Theories - Cyclical or Structural - What determines it?

Theory 1 (PSNCR and the trade cycle) shows that the PSNCR will tend to vary with the economic cycle. If this happens over a number of years and the PSNCR fluctuates around an average value of zero, then the government doesn't need to worry about it too much. A recession may increase it, but the onset of recovery will help it fall again. If this is the case then the PSNCR is termed a cyclical PSNCR.

However, it will often be the case that the value that the PSNCR fluctuates around is far from zero. This means that the government is borrowing all the time. In other words, it is borrowing over the long term. Where this happens, this part of the PSNCR is termed a structural PSNCR. Governments do need to worry more about a structural PSNCR as it is a long-term one, and they need to think about how they can reduce it. They have two main alternatives:

If they don't do either of these, there will be a permanent PSNCR and the national debt

- Increase taxes

- Reduce government expenditure

will grow over time.

PSNCR and the Money Supply - The effect of borrowing on the money supply

If the PSNCR is high, this means that the government is spending much more than it is receiving in tax revenue. It follows then that it is putting more money into the banking system (from its spending) than it is taking out of it (from taxes). This will increase the money supply in the economy. This may be undesirable as many economists believe that excessive money supply growth will cause inflation. This is a view held particularly by Monetarist economists and Classical economists.

The aim of governments should therefore be to keep the value of the PSNCR down to help keep money supply growth down.

PSNCR and the National Debt - How indebted are we?

The national debt is the total amount of borrowing accumulated by the government that is still outstanding. It is the total amount that the government owes to individuals and institutions.

Think of the national debt as the level of water in a tank. Each year the government borrows more. The amount it borrows is the PSNCR. This is equivalent to a tap filling up the tank - the amount of water (debt) is growing. However, at the same time, the government pays off some of its debts each year. This is like water flowing out of the tank.

If the amount flowing into the tank (the PSNCR) is greater than the amount going out (debt paid off), then the water level (the national debt) will rise. If on the other hand the amount flowing into the tank (the PSNCR) is smaller than the amount going out (debt paid off), then the water level (the national debt) will fall.

The diagram below shows this:

She said what? About who? Shameful celebrity quotes on Search Star!

Messenger on the move. Text MSN to 63463 now!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)