If the Tories get their way, within five years the UK will have a smaller public sector than any major developed nation

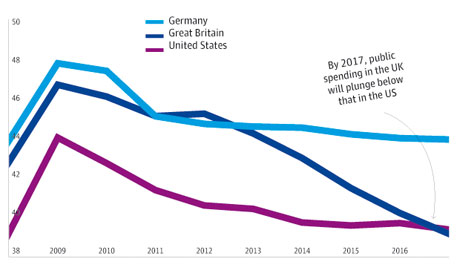

Government spending as a percentage of national GDP. Photograph: IMF WEO Database Oct 2012

This column is normally accompanied by a photo; an illustration that takes its cue from the text. But not today. The chart you see on this page is plainly not decorative: it is the main event. All I'm going to discuss is its implications.

Drawing on IMF figures published last week, the graph compares what will happen to government spending in Britain up to 2017 with the outlook for Germany and the US. And what it shows is that the UK will plunge from public spending on a par with Germany in 2009, to spending less than the US by 2017. Had France, Sweden or Canada been included on this graph, the UK would still come bottom. If George Osborne gets his way, within the next five years, Britain will have a smaller public sector than any other major developed nation.

Fan or critic, nearly everyone now agrees that this government wants to shrink the state, but very few take on board what that means. This graph shows just how radical those ministerial plans are. Particularly striking is the fact that Britain will end up spending less as a proportion of its national income than even the US, the international byword for a decrepit public sector. According to Peter Taylor-Gooby, professor of social policy at Kent, this will be the first time it has happened since at least 1980 and possibly in recorded history. For it to take place within half a decade is a shift so dramatic that few people in frontline politics, let alone among the electorate, have understood its implications.

Forget all that ministerial guff about the necessity of cutting the public sector to spur economic growth. Had that argument been true, British businesses would be in leonine form by now, instead of their current chronic enfeeblement. It was notable at last week's Tory party conference how Osborne and David Cameron didn't even try to argue for the economic benefits of austerity – how could they? – but grimly asserted that there was no alternative.

Forget, too, the argument that only cuts have kept Britain's borrowing costs from rocketing. In the IMF's summer healthcheck for the UK was another chart which showed that the only nations where interest rates had spiralled upwards were those in the eurozone, and those without control of their own currency and monetary policy. Every other major economy, no matter what their debt load, was able to borrow from the financial markets as cheaply as ever.

Strip away the usual economic and financial alibis for such drastic austerity and what you're inevitably left with is a purely political motive: namely, a desire to transform the British state from being recognisably European, with continental levels of public spending, to something sub-American in its miserliness.

Let me make two caveats. First, there was no way Britain was going to maintain public spending at 2009 levels. That year, the Labour government threw the kitchen sink at the economy, after which you would expect some belt-tightening. Still, as Carl Emmerson of the Institute for Fiscal Studies points out, after both world wars, the level of public spending in Britain rose permanently; you might expect something similar after a once-in-a-lifetime financial crisis. Given how fast Britain is ageing, and how much we will need to spend on pensions and care for the elderly, there is no reason why the state in Britain should shrink back to some magic level of 40% of the economy.

Second, this chart is based on current US budget plans: if Mitt Romney moves into the White House next January, or even if Barack Obama is re-elected and has to strike a bargain with intransigent Republicans, then Washington is also likely to make stringent cuts. But that last qualification only reinforces the larger argument. Whether in Britain or the US, the right are trying to whip the rest of us into a giant race to the bottom, where public services, welfare entitlements and employment rights are all to be tossed overboard.

Cameron admitted as much in last Wednesday's conference speech. Lumping together Nigeria with China and India and Brazil, he described them as "the countries on the rise … lean, fit, obsessed with enterprise, spending money on the future – on education, incredible infrastructure and technology". As anyone who has ever tried to keep a car on the potholed roads of Bihar, in northern India, will know, that description is a giant porky. But Cameron wanted to draw a comparison with "the countries on the slide … fat, sclerotic, over-regulated, spending money on unaffordable welfare systems, huge pension bills, unreformed public services".

From compassionate Conservative to growth rainmaker to state-shrinker, Cameron has gone through a huge change since 2005. But that is nothing like what lies ahead for the rest of Britain in the next five years. Prepare yourself for welfare to be downsized into American-style workfare, for public-sector jobs to be turned into a second-class employment and for services, from school to healthcare, to demand that users pay more to get something decent. The future is American.