'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Saturday, 25 February 2023

Tuesday, 20 December 2022

Saturday, 26 November 2022

Sunday, 20 November 2022

Tuesday, 1 November 2022

Saturday, 29 October 2022

Imran Khan has Pakistani army ducking & defending. Why it’s a historic moment for the subcontinent

Since its founding, Pakistan’s army has built a consistent record of launching wars on India and losing. It is a record of unblemished consistency. There is, however, another battlefield where it has an equally consistent record of winning. Which is where it is staring at defeat. We will elaborate on this in just a bit.

On fighting and losing wars with India, there will obviously be some nitpicking. The tough fact is, after so many wars, this army has lost almost half of Pakistan (Bangladesh), destroyed its polity, institutions, economy and entrepreneurship, and driven out its talent. Finally, it has even less of Kashmir (think Siachen) than it started out with.

So where is it that its record of winning has been equally consistent and it is now on the retreat?

---

Check out this entire press conference by Lt Gen. Nadeem Ahmed Anjum, the serving chief of the almighty Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), which vanquished the Soviet and American powers, the KGB and the CIA, in Afghanistan. Chaperoned by Lt Gen. Babar Iftikhar, the chief of Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR), he has spoken for nearly an hour and a half. All of this was invested in defending himself, the ISI, his chief and the army.

Now, never mind that Elon Musk has stolen that metaphor for posterity, please allow us also to use it: Let that sink in. This is the ISI that all of Pakistan both loved and feared, loved and loathed, that friend and foe held in awe. It only had to wink, nod and sometimes nudge, and most of the Pakistani media would fall in line. If you didn’t, you might end up in jail, exile, a corpse in a gutter or in a strange land. In some cases, all of these. Think Arshad Sharif, the former ARY anchor. He was fired and exiled, as was his boss. Sharif turned up dead in Kenya, apparently shot by the police in a matter of mistaken identity. If you believe that, you must be high on something totally illegal.

Now, we had the ISI chief, institutionally among the most powerful men in the world at any time, at a press conference with a hand-picked friendly audience (most of the respected publications were excluded). Usually, his word and his chief’s were an order for Pakistan’s media, politicians, and often also the judiciary. The chief of ISPR was his constant messenger.

Now, both of them, speaking on behalf of their institution, were claiming victimhood. When the Pakistani army goes to the media complaining about a political leader who they evidently fear, you know that its politics has taken a historic turn.

---

Pakistan’s army is brilliant at scrapping with its political class and winning. Now it fears defeat at the hands of its politicians too. To that extent, Imran Khan might be on the verge of a victory that would mean even more in political terms than his team’s cricket World Cup win in 1992. If the Pakistani army can finally be defeated by a popular, if populist, civilian force, it’s a history-defining moment for the subcontinent.

It’s history-defining because an institution that was never denied its supreme power except for a few years after the 1971 defeat is now seeking public sympathy with its back to the wall under a mere civilian’s onslaught. Its word used to be a command for any government of the day. It could hire, fire, jail, exile, or murder prime ministers serving, former and prospective. To understand that, you do not have to go far.

In 2007, it looked as if Benazir Bhutto was on the ascendant, after her return from her second long exile (the first return was in 1986, which I had covered in this India Today cover story from Pakistan). She was assassinated despite so many warnings that her life was in danger. Nobody has been punished yet. It’s buried in Pakistan’s history of conspiracies and eternal mysteries like so many others. Her party’s government was kneecapped and her husband subsequently reduced to an inconsequential, titular president.

Nawaz Sharif came back with a comfortable majority. He too grew “delusional”, from his army’s point of view, in beginning to believe that he was a real prime minister. By 2018, this army, under a chief he had appointed, had conspired and contrived to get rid of him, jail and exile him. It ensured that his party didn’t get a majority in the election that followed. In the process, they also built, strengthened and employed Pakistan’s most regressive Sunni Islamist group, Tehreek-e-Labbaik.

---

Imran Khan was then the army’s candidate, and does it matter if he fell short of a majority? The army and the ISI collected enough small parties and independents to give him a comfortable majority. Albeit at their sufferance. A majority was no issue for one seen as the boy of the boys.

Until, this ‘boy’ also began to believe that he was a real prime minister and was causing ‘discomfort’ at the army GHQ.

Worse, his delusions weren’t just domestic. He was now seeing himself as the new leader of the Islamic Ummah, a 21st-century Caliph of sorts in his own right. He was talking in shariat terms, bringing a Quranic curriculum, building a new agenda that was as Islamist as it was anti-West. Both of these alarmed the army.

In the same state of political ‘high’, Imran started to believe he now bossed the army. That’s how the first, and decisive, fights broke out over top-level appointments. The first was over the appointment of the new ISI chief. The army chief had his way with Nadeem Anjum and Imran lost out over his insistence on continuing with Lt Gen. Faiz Hameed. This fight was, however, like a crucial league match before the final — the appointment of the new chief in November.

Think about what is the one thread that’s common to this entire ugly story of intrigue, betrayal, and now it seems, assassination too? General Qamar Javed Bajwa has been the army chief through all of these years. Appointed by Nawaz Sharif who he later fired and exiled, given a three-year extension by Imran Khan who he first created and then got fired, and now challenged by him.

Over the past five decades, two great political families have fought for democracy in Pakistan in their own patchy ways, although mostly by keeping the army GHQ on their sides. Both, the Bhutto family’s Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) and the Sharifs’ Pakistan Muslim League (PML-N) are now tired and spent forces. One because of its shrinking footprint from Punjab, and the other because its only popular leader, Nawaz Sharif, is hesitant to leave the safety of exile in London and join the fight at home. Both are counting on the army to save their throne and skins.

This used to be business as usual. If the army was on your side, the world was yours in Pakistan. The reason these aren’t usual times is that today it is the army that’s staring at the greatest, scariest existential threat to its power and stature. This threat has come from a populist, riding democratic power. So what if it’s that often nutty and deeply flawed Imran Khan. Did we ever argue democracy is perfect?

Wednesday, 28 September 2022

Friday, 16 September 2022

Sunday, 12 June 2022

Bitcoin: It’s always difficult to get people to understand something if their wealth depends on their not understanding it.

Bitcoin mining has previously produced lucrative gross margins as high as 90%. Photograph: Jack Guez/AFP/Getty Images

Bitcoin mining has previously produced lucrative gross margins as high as 90%. Photograph: Jack Guez/AFP/Getty Images In the bad old days, prospecting for gold was a grisly business involving hysterical crowds, pickaxes, digging, the wearing of appalling hats, standing in rivers panning for nuggets, “staking” claims and so on. The California gold rush of 1848-55, for example, brought 300,000 hopefuls to the Sierra Nevada and northern California and involved the massacre of thousands of Indigenous people.

In our day, the new gold is bitcoin, a cryptocurrency, and prospecting for it has become a genteel armchair activity, although it is called “mining”, for old times’ sake. What it actually involves is using computers to perform unfathomably complicated calculations to create cryptographic “hashes” – codes that are, in practical terms, uncrackable.

Sounds intimidating, doesn’t it? But in reality anyone can play the game. You just have to have the right kit – a special bitcoin-mining computer called an Asic (application-specific integrated circuit). These gizmos are readily available online. I’m looking at one as I write: the Bitmain Antminer S19, which costs $6,999 (£5,600) and can do 95 terahashes – 95tn calculations – every second.

Mining is a misleading term for the computational work that’s needed to validate transactions on the blockchain – the cryptographically protected distributed ledger that underpins bitcoin. For every “block” that a miner is able to validate, they are rewarded with a number (currently 6.3) of new bitcoins. The value of the reward is tied to the prevailing price of the currency at the time. Not so long ago, for example, when each bitcoin stood at $68,000, that reward was worth nearly $430,000.

So you can understand why bitcoin mining looks a bit like a contemporary version of what happened in California in the 1840s. While most of the hopeful arrivals then were Americans, there were also thousands from Latin America, Europe, Australia and China. The Judge Business School in Cambridge, which has been tracking bitcoin mining for years, now finds that the US, with 37.84% of global hashrates, remains the biggest location, followed by China (21.11%), Kazakhstan (13.22%), Canada (6.48%) and Russia (4.66%).

So bitcoin mining has become a global phenomenon. And while here and there there are small outfits diversifying into it, such as the Californian pancake-batter maker that bought an Asic after pancake sales plunged during the pandemic, most miners are now industrial-scale operations with large sheds of Asics in serried racks, looking for all the world like small-scale data centres of the kind run by Google and co.

And, like data centres, they are power-hungry. That Bitmain Antminer machine, for example, has a power rating of 3,250 watts. It was recently estimated that bitcoin consumes about 110 terawatt hours per year, which is 0.55% of global electricity production, or roughly equivalent to the annual energy draw of countries such Malaysia or Sweden.

For many operators, bitcoin mining has up to now been an astonishingly lucrative activity, with gross margins sometimes as high as 90%. But suddenly things have changed. First, bitcoin’s price has plunged – from its peak of $68,000 to $30,587 as I write this. And second, electricity prices have soared – by up to 70% in parts of the world, leading some industry experts to calculate that mining a single bitcoin can now cost up to $25,000. So the industry finds itself squeezed at both ends. Just like any ordinary business, in other words.

There’s an agreeable sense of schadenfreude in all this. Bitcoin has been a fascinating phenomenon from the very beginning, but one that morphed under the pressure of greed. Originally conceived as a currency – that is, as a means of payment – it rapidly became perceived as an asset class and, in a time of low interest rates, was the subject of an hysterical speculative bubble that now seems to have deflated, even if it hasn’t definitively burst.

Although it was predictable from the outset that, as the currency evolved, maintenance of its underpinning cryptographic blockchain would become ever-more onerous, it took a long time for the environmental consequences of that fact to be realised. But perhaps that’s a hallmark of every speculative bubble. It’s always difficult to get people to understand something if their wealth – real or anticipated – depends on their not understanding it. Meanwhile, the rest of us are left with the realisation that even the coolest idea can fry the planet.

Sunday, 6 March 2022

Monday, 17 January 2022

Welcome to the era of the bossy state

The relationship between governments and businesses is always changing. After 1945, many countries sought to rebuild society using firms that were state-owned and -managed. By the 1980s, faced with sclerosis in the West, the state retreated to become an umpire overseeing the rules for private firms to compete in a global market—a lesson learned, in a fashion, by the communist bloc. Now a new and turbulent phase is under way, as citizens demand action on problems, from social justice to the climate. In response, governments are directing firms to make society safer and fairer, but without controlling their shares or their boards. Instead of being the owner or umpire, the state has become the backseat driver. This bossy business interventionism is well-intentioned. But, ultimately, it is a mistake.

Signs of this approach are everywhere, as our special report explains. President Joe Biden is pursuing an agenda of soft protectionism, industrial subsidies and righteous regulation, aimed at making the home of free markets safe for the middle classes. In China Xi Jinping’s “Common Prosperity” crackdown is designed to curb the excesses of its freewheeling boom, and create a business scene that is more self-sufficient, tame and obedient. The European Union is drifting away from free markets to embrace industrial policy and “strategic autonomy”. As the biggest economies pivot, so do medium-sized ones such as Britain, India and Mexico. Crucially, in most democracies, the lure of intervention is bipartisan. Few politicians fancy fighting an election on a platform of open borders and free markets.

That is because many citizens fear that markets and their umpires are not up to the job. The financial crisis and slow recovery amplified anger about inequality. Other concerns are more recent. The world’s ten biggest tech companies are over twice as big as they were five years ago and sometimes seem to behave as if they are above the law. The geopolitical backdrop is a far cry from the 1990s, when the expansion of trade and democracy promised to go hand in hand, and from the cold war when the West and the Soviet Union had few business links. Now the West and totalitarian China are rivals but economically intertwined. Gummed-up supply chains are causing inflation, reinforcing the perception that globalisation is overextended. And climate change is an ever more pressing threat.

Governments are redesigning global capitalism to deal with these fears. But few politicians or voters want to go back to full-scale nationalisation. Not even Mr Xi is keen to reconstruct an empire of iron and steel plants run by chain-smoking commissars, while Mr Biden, despite his nostalgia for the 1960s, need only walk through America’s clogged West Coast ports to recall that public ownership can be shambolic. At the same time the pandemic has seen governments experiment with new policies that were unimaginable in December 2019, from perhaps $5trn or more of handouts and guarantees for firms to indicative guidance on optimal spacing of customers in shopping aisles.

This opening of the interventionist mind is coalescing around policies that fall short of ownership. One set of measures claims to enhance security, broadly defined. The class of industries in which government direction is legitimate on security grounds has expanded beyond defence to include energy and technology. In these areas governments are acting as de facto central planners, with research and development (r&d) spending to foster indigenous innovation and subsidies to redirect capital spending. In semiconductors America has proposed a $52bn subsidy scheme, one reason why Intel’s investment is forecast to double compared with five years ago. China is seeking self-sufficiency in semiconductors and Europe in batteries.

The definition of what is seen as strategic may well expand further to include vaccines, medical ingredients and minerals, for example. In the name of security, most big countries have tightened rules that screen incoming foreign investment. America’s mesh of punitive sanctions and technology export controls encompasses thousands of foreign individuals and firms.

The other set of measures aims to enhance stakeholderism. Shareholders and consumers no longer have uncontested primacy in the hierarchy of groups that firms serve. Managers must weigh the welfare of other constituents more heavily, including staff, suppliers and even competitors. The most visible part of this is voluntary, in the form of “esg” investing codes that score firms for, say, protecting biodiversity, local people or their own workers. But these wider obligations may become harder for firms to avoid. In China Alibaba has pledged a $15bn “donation” to the Common Prosperity cause. In the West stakeholderism may be enforced through the bureaucracy. Central banks and public pension funds may shun the securities of firms judged to be anti-social. America’s antitrust agency, which once safeguarded consumers alone, is mulling other aims such as helping small firms.

The ambition to confront economic and social problems is admirable. And so far, outside China at least, bossier government has not hurt business confidence. America’s main stockmarket index is over 40% higher than it was before the pandemic, while capital spending by the world’s largest 500-odd listed firms is up by 11%. Yet, in the longer term, three dangers loom.

High stakes

The first is that the state and business, faced by conflicting aims, will fail to find the best trade-offs. A fossil-fuel firm obliged to preserve good labour relations and jobs may be reluctant to shrink, hurting the climate. An antitrust policy that helps hundreds of thousands of small suppliers will hurt tens of millions of consumers who will end up paying higher prices. Boycotting China for its human-rights abuses might deprive the West of cheap supplies of solar technologies. Businesses and regulators focused on a single sector are often ill-equipped to cope with these dilemmas, and lack the democratic legitimacy to do so.

Diminished efficiency and innovation is the second danger. Duplicating global supply chains is extraordinarily expensive: multinational firms have $41trn of cross-border investments. More pernicious in the long run is a weakening of competition. Firms that gorge on subsidies become flabby, whereas those that are protected from foreign competition are more likely to treat customers shabbily. If you want to rein in Facebook, the most credible challenger is TikTok, from China. An economy in which politicians and big business manage the flow of subsidies according to orthodox thinking is not one in which entrepreneurs flourish.

The last problem is cronyism, which ends up contaminating business and politics alike. Firms seek advantage by attempting to manipulate government: already in America the boundary is blurred, with more corporate meddling in the electoral process. Meanwhile politicians and officials end up favouring particular firms, having sunk money and their hopes into them. The urge to intervene to soften every shock is habit-forming. In the past six weeks Britain, Germany and India have spent $7bn propping up two energy firms and a telecoms operator whose problems have nothing to do with the pandemic.

This newspaper believes that the state should intervene to make markets work better, through, for example, carbon taxes to shift capital towards climate-friendly technologies; r&d to fund science that firms will not; and a benefits system that protects workers and the poor. But the new style of bossy government goes far beyond this. Its adherents hope for prosperity, fairness and security. They are more likely to end up with inefficiency, vested interests and insularity.

Sunday, 5 December 2021

The Long Shadow of Deobandism in South Asia

Illustration by Joanna Andreasson for New Lines

Illustration by Joanna Andreasson for New LinesI might have been 11 when I first heard the word “Deobandi.” My family had just returned to Islamabad after eight years in New York, where my father served as a mid-ranking official at Pakistan’s mission to the United Nations. A year had passed since military ruler, Gen. Zia-ul-Haq, began subjecting Pakistan to his despotic Islamization agenda, and I was being exposed to a lot more than my brain could process. My dad despised Zia for two separate reasons. The first was obviously political. My father was a democrat and a staunch supporter of ousted Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who had been executed after Zia’s 1977 coup. The second was religious. Our ancestors were from the Barelvi sect, which constituted the vast majority of Pakistanis at the time and has been the historical rival of the Deobandis, whom Zia had begun to capacitate to gain legitimacy for his regime. For the most part a secular individual, my father had always been passionate about our supposed ancestral lineage to medieval Sufi saints. Deobandis are Hanafi Sunni Muslims like Barelvis, but for him they represented local variants of the extremist brand known as Wahhabism, which originated in the Arabian Peninsula. And with Zia empowering their mullahs, mosques and madrassas, he thought it was his duty to protect his heritage, and I was given a crash course on the sectarian landscape.

While most Islamists in the Arab/Muslim world are more activists than religious scholars, in South Asia the largest Islamist groups are led by traditional clerics and their students. And the Deobandi sect has been in the forefront of South Asian Islamism, with the Taliban as its most recent manifestation. The Deobandis’ influence, reach and relevance in a vast and volatile region like South Asia is immense, yet they are little understood in the West. Western scholarship and commentary tend to be more focused on the movement’s counterparts in the Arab world, namely the Muslim Brotherhood and Wahhabi Salafism.

Deobandism was propelled by ulema lamenting at the loss of Muslim sovereignty in India. Different dynastic Muslim regimes had ruled over various regions in the subcontinent since the late 10th and early 11th century. The ulema had been part of the South Asian Muslim political elite, but their public role was always subject to a tug of war with the rulers and evolved over time.

They had a strong presence in the royal court from the time of the first Muslim sultanistic dynasty in the subcontinent: the Turkic Ghaznavids (977-1170), who broke off from the Persian Samanids (who themselves had declared their independence from the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad). It was during this era that the role of ulema began to change in that a great many of them from Central Asia invested in proselytization and spiritual self-discipline. This spiritual approach gained ground and distinguished itself from the legalistic approach of the ulema. The former took on a social and grassroots role while the latter continued to focus on directly influencing the sultan and, through his sultanate, the realm at large. Behind both movements were ulema who, to varying degrees, subscribed to Sufism. The difference was between those who swung heavily toward scriptural scholarship and those who were open to unorthodox ideas and practices in keeping with what they perceived as the need to accommodate local customs and exigencies. This divide would remain contained and the ulema would enjoy an elite status, which continued through the era of the Ghaurids (1170-1215) — an Afghan dynasty.

Essentially the ulema provided legitimacy for the rulers and in exchange received largesse and influence in matters of religion. It was under the Sultanate of Delhi (1206-1525) that the ulema were appointed to several official state positions, largely within the judiciary. In addition, a state law enforcement organ called hisbah was created for ensuring that society conformed to shariah, which is the origin for the modern-day agencies in some Muslim governments assigned the task of “promoting virtue and preventing vice.” It was an arrangement that allowed the ruler to keep the ulema in check and incapable of intruding into matters of statecraft.

After the Delhi Sultanate collapsed in 1526, it was replaced by another Turkic dynasty, the Mughals, under whom the ulema were marginalized. In his award-winning 2012 book, “The Millennial Sovereign: Sacred Kingship and Sainthood in Islam,” Azfar Moin, who heads the University of Texas at Austin’s Religious Studies Department, explains that during the reigns of Akbar (r. 1542-1605), his son Jehangir (r. 1605-27) and his grandson Shah Jehan (r. 1628-58), the ulema would remain in political wilderness.

It was Akbar’s great-grandson, Aurangzeb (r. 1658-1707), who not only restored the ulema to their pre-Akbar status but also radically altered the empire’s structure by theocratizing it. His Islamization agenda was a watershed moment, for it created the conditions in which the ulema would eventually gain unprecedented ground. What enabled the advance would be the fact that Aurangzeb was the last effective emperor, leading to not just the collapse of the Mughal empire but also the ascendance of British colonial rule. These two sequential developments would essentially shape the conditions in which Deobandism, and later on, radical Islamism, would emerge, as argued by Princeton scholar Muhammad Qasim Zaman explains in in his seminal 2007 book “The Ulama in Contemporary Islam: Custodians of Change.”

Over the course of the next two centuries, an ulema tendency that stressed the study of original Islamic sources and deemphasized the role of the rational sciences gained strength. Started by Shah Abdur Rahim, a prominent religious scholar in Aurangzeb’s royal court, this multigenerational movement was carried forward by his progeny, which included Shah Waliullah Delhawi, Shah Abdul Aziz and Muhammad Ishaq. This line of scholars represented the late Mughal era puritanical movement.

Delhawi, who was its most influential theoretician, was a contemporary of the founder of Wahhabism in the Arabian Peninsula, Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. The two even studied at the same time in Medina under some of the same teachers who exposed them to the ideas of the early 14th century iconoclastic Levantine scholar Ibn Taymiyyah. Salafism and Deobandism, the two most fundamentalist Muslim movements of the modern era, simultaneously emerged in the Middle East and South Asia, respectively. According to the conventional wisdom, the extremist views of Wahhabism spread from the Middle East to South Asia. In reality, however, Delhawi and Wahhabism’s founder drank from the same fountain in Medina — under an Indian teacher by the name of Muhammad Hayyat al-Sindhi and his student Abu Tahir Muhammad Ibn Ibrahim al-Kurani. A major legacy of Delhawi is Deobandism, which arose as Wahhabism’s equivalent in South Asia in the late 19th century. Similar circumstances led to the near simultaneous rise of the Muslim Brotherhood in the Middle East and Jamaat-i-Islami in South Asia in the early 20th century. These connections go to show how the two regions often influence each other in more significant ways than usually acknowledged.

For this clerical movement shaped by Delhawi, Muslim political decay in India was a function of religious decline, the result of the contamination of thought and practice with local polytheism and alien philosophies. Insisting that the ulema be the vanguard of a Muslim political restoration, these scholars established a tradition of issuing fatwas to provide common people with sharia guidance for everyday issues. Until then, such religious rulings had been largely the purview of the official ulema who held positions in the state. This group was responsible for turning the practice into a nongovernmental undertaking at a time when the state had become almost nonexistent. By the time Ishaq died in the mid-19th century, he had cultivated a group of followers including Mamluk Ali and Imdadullah Mujhajir Makki, who were mentors of the two founders of Deobandism, Muhammad Qasim Nanutavi and Rashid Ahmad Gangohi.

Renowned American scholar of South Asian Islam Barbara Metcalf in her 1982 book “Islamic Revival in British India: Deoband, 1860-1900” explains how the emergence of Deobandism was rooted in both ideological and practical concerns. It began when Nanutavi and Gangohi established the Dar-ul-Uloom seminary in the town of Deoband, some 117 miles north of Delhi, in 1866 — eight years after participating in a failed rebellion against the British conquest of India.

These two founders of the movement had already tried forming an Islamic statelet in a village called Thana Bhawan, north of Delhi, from where they sought to wage jihad against the British, only to be swiftly defeated. William Jackson explains in great detail, in his 2013 Syracuse University dissertation, the story of how the two formed a local emirate — a micro-version of the one achieved by the Taliban. Their mentor Makki became emir-ul-momineen, the Leader of the Faithful, and the two served as his senior aides — Nanutavi as his military leader, and Gangohi served as his judge. The tiny emirate was crushed by the British within a few months. Imdadullah fled to Mecca, Gangohi was arrested and Nanautavi fled to Deoband, where he sought refuge with relatives.

Realizing there was no way to beat the British militarily, Nanautavi sought to adopt the empire’s educational model and established a school attached to a mosque. His decision would be instrumental in shaping the course of history, ultimately helping to lay the groundwork for Indian independence, the creation of Pakistan and the rise of modern jihadist groups including the Afghan and Pakistani Taliban.

In Nanautavi’s point of view, European Christians were now masters of the land long ruled by Indian Muslims. He thus envisioned the seminary as an institution that would produce a Muslim vanguard capable of restoring the role of the ulema in South Asian politics and even raising it to unprecedented levels. His priority was religious revival and, after Gangohi was released from prison, the madrassa at Deoband became the nucleus for a large network of similar schools around the country.

After Nanautavi died in 1880, Mahmud Hassan, the first student to enroll in Dar-ul-Uloom, led the Deobandi movement. Hassan transformed the movement from focusing on a local concern to one with national and international ambitions. Students from Russia, China, Central Asia, Persia, Turkey, the Levant and the Arabian Peninsula came to study at the seminary under his leadership. By the end of the First World War, more than a thousand graduates had fanned out across India. Their main task was to expunge ideas and practices that had crept into Indian Muslim communities through centuries of interactions with the Hindu majority.

This quickly antagonized the pre-dominant Muslim tendency that was rooted in Sufi mysticism and South Asian Islamic traditions. This movement started to organize in response to the Deobandis, in another Indian town called Bareilly, and was led by Ahmed Raza Khan (1856-1921). The Barelvis, as the rival movement came to be known, viewed the Deobandis as a greater threat to their religion and country than British colonial rule. This rivalry continues to define religious and political dynamics till this day, across South Asia.

Although the Deobandis viewed India as Dar-ul-Harb (Dominion of War), they initially did not try to mount another armed insurrection. Instead, they opted for a mainstream approach to politics that called for Hindu-Muslim unity. The Barelvis, meanwhile, took up controversial positions that unintentionally helped the Deobandis gain support. In particular, a fatwa by the Barelvi leader, Ahmed Raza Khan, in which he ruled that the Ottoman Empire was not the true caliphate, angered many Indian Muslims and drove them closer to the pan-Islamic, anti-British vision of the Deobandis. In fact, given the success of the Deobandi movement on a sectarian level, it never really viewed the Barelvis as a serious challenge.

While Deobandis and Barelvis were in the making, so was a modernist Muslim movement led by Sir Syed Ahmed Khan (1817-98). A religious scholar turned modern intellectual, Sir Syed hailed from a privileged family during the late Mughal era and worked as a civil servant during British rule. From his point of view, Muslim decline was a direct result of a fossilized view of religion and a lack of modern scientific knowledge. Sir Syed would go on to be the leader of Islamic modernism in South Asia through the founding of the Aligarh University. The university produced the Muslim elite, which would, almost half a century after Sir Syed’s death, found Pakistan.

Sir Syed’s prognosis of the malaise affecting the Muslims of India was unique and clearly different from that of the long line of religious scholars who saw the problem as a function of the faithful having drifted away from Islam’s original teachings. The loss of sovereignty to the British combined with the rise of men like him who advocated a cooperative approach toward the British and an embracing of European modernity would lead the founders of Deoband to adopt their own pragmatic approach but one that laid heavy emphasis on religious education. The Deobandis viewed Sir Syed’s Islamic modernism as their principal competitor. In other words, the Aligarh movement also developed around a university — but one that emphasized Western secular education — represented a major challenge, and not just politically but also religiously in that it offered an alternative paradigm.

Barely half a century after its founding, the Deobandi movement had established seminaries across India, from present-day Bangladesh in the east to Afghanistan in the west. Such was its influence that in 1914, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, the leader of the secular Pashtun Khudai Khidmatgars movement, visited the Dar-ul-Uloom. Ghaffar Khan, who would later earn the moniker “The Frontier Gandhi,” met the Deobandi leader Mahmud Hassan to discuss the idea of establishing a base in the Pashtun areas of northwest India, from which they could launch an independence rebellion against the British. Harking back to the armed struggle of their forerunners, the Deobandis, once again, tried their hand at jihad — this time on a transnational scale.

With the help of Afghanistan, Ottoman Turkey, Germany and Russia, Hassan sought to foment this insurrection, believing that Britain would be too focused on fighting the First World War on the battlefields of Europe to be able to deal with an uprising in India. The plan was ambitious but foolhardy. Hassan wanted to headquarter the insurgent force in Hejaz, in modern-day Saudi Arabia, with regional commands in Istanbul, Tehran and Kabul. He traveled to Hejaz, where he met with the Ottoman war minister, Anwar Pasha, and the Hejaz governor, Ghalib Pasha. The Ottomans strongly supported an Indian rebellion as a response to the British-backed Arab revolt against them. The plan failed in great part because the Afghan monarch, Emir Habibullah Khan, would not allow an all-out war against the British be waged from his country’s soil. Hassan, the Deoband leader, was ensconced in Mecca when he was arrested by the Hashemite ruler of the Hejaz, Sharif Hussein bin Ali, and handed over to the British. He was imprisoned on the island of Malta.

During the four years that Hassan was jailed, several key developments took place back home in India. The most important was the launch of the 1919 Khilafat (Caliphate) Movement by a number of Muslim notables influenced by Deobandism. As prominent historian of South Asian Islam, Gail Minault, argues in her 1982 book “Religious Symbolism and Political Mobilization in India,” the Khilafat Movement, which lobbied Turkey’s new republican regime to preserve the caliphate, was actually a means of mobilizing India’s Muslims in a nationalist struggle against the British. This would explain why the movement received the support of Mahatma Gandhi in exchange for backing his Non-Cooperation Movement against the British. At around the same time, several Deobandi ulema created Jamiat Ulema-i-Hind (JUH), which would become the formal political wing of the movement – engaging in a secular nationalist struggle.

When Hassan was released from prison and returned to India, Gandhi traveled to Bombay to receive him. Hassan went on to issue a fatwa in support of the Khilafat and Non-Cooperation movements, which was endorsed by hundreds of ulema. Under his leadership, the Deobandis also supported Gandhi’s candidacy for the presidency of the Indian National Congress. The move was in keeping with their point of view that the Hindu majority was not a threat to Islam and the real enemies were the British.

As the Deobandi movement pushed for Hindu-Muslim unity, it underwent another leadership change. Ill from tuberculosis, Hassan died in November 1920, six months after his release from prison. He was succeeded by his longtime deputy Hussain Ahmed Madani, who engaged in a major campaign calling for joint Hindu-Muslim action against the British. With Madani at the helm, the Deobandis argued that movements organized along communal lines played into the hands of the colonial rulers and advanced the idea of “composite nationalism.” A united front was needed to end the British Empire’s dominance. This view ran counter to the atmosphere of the times and, following the collapse of the Deobandis’ transnational efforts, the movement’s nationalist program also floundered.

The All-India Muslim League (AIML), headed by the future founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, was growing in strength and steering Indian Muslims toward separatism. At the same time, the Deobandis’ JUH and Gandhi’s Indian National Congress intensified their demand for Indian self-government. The situation came to a head with massive nationwide unrest in 1928. To defuse the situation, the British asked Indian leaders to put forth a constitutional framework of their own. In response, the Indian National Congress produced the Nehru Report, a major turning point for the Deobandis. The report by their erstwhile allies ignored the JUH demand for a political structure that would insulate Muslim social and religious life from central government interference. This led dissenting members of the JUH and among the wider Deobandi community to join AIML’s call for Muslim separatism.

While prominent Deobandi scholar Ashraf Ali Thanvi would initiate the break, it was his student, Shabbir Ahmed Usmani, who led the split. Usmani would spearhead a reshaping of the Deobandi religious sect and play a critical role in charting the geopolitical divide that still defines South Asia today. In 1939, Thanvi issued a fatwa decreeing that Muslims were obligated to support Jinnah’s separatist AIML. He then resigned from the Deoband seminary and spent the four remaining years of his life supporting the creation of Pakistan.

Thanvi and Usmani realized that if the Deobandis did not act, the Barelvis — already allied with the AIML — could outmaneuver them. Better organized and one step ahead of their archrivals, the Deobandis were able to position themselves as the major religious allies of the AIML. It is important to note, however, that many Deobandis remained loyal to Madani’s more inclusive approach. They viewed his stance as in keeping with the Prophet Muhammad’s Compact of Medina, which had ensured the cooperation of various non-Muslim tribes. In contrast, Usmani and the renegade Deobandis had long been deeply uncomfortable with the idea of Hindu-Muslim unity, which conflicted with their religious puritanism. When Usmani established Jamiat Ulema Islam (JUI) in 1945 as a competitor to Madani’s JUH, the deep schism within the Deoband movement had reached a point of no return. Usmani’s insurrection came at the perfect time for Jinnah, a secular Muslim politician with an Ismaili Shia background. Jinnah had long sought to weaken JUH’s opposition to his Muslim separatist project; the support of Usmani lent religious credibility to his cause: creating the state of Pakistan.

After partition in 1947, the spiritual home of the Deobandi movement remained in India, but Pakistan was now its political center. When they founded JUI, Usmani and his followers already knew that it was way too late in the game for their group to be the vanguard leading the struggle for Pakistan. The AIML had long assumed that mantle, but it was not too late for the JUI to lead the way to Islamizing the new secular Muslim state. In fact, Jinnah’s move to leverage the Islamic faith to mobilize mass demand for a secular Muslim homeland had left the character of this new state deeply ambiguous. Such uncertainty provided the ideal circumstances for JUI to position itself at the center of efforts to craft a constitution for Pakistan. In the new country’s first Parliament, the Constituent Assembly, JUI spearheaded the push for an “Islamic political system.”

The death of secularist Jinnah in September 1948 created a leadership vacuum, which helped JUI’s cause. As a member of the assembly, the JUI leader Usmani played a lead role in drafting the Objectives Resolution that placed Islam at the center of the constitutional process. The resolution stated that “sovereignty over the entire universe belongs to God Almighty alone and the authority which He has delegated to the State of Pakistan.” It went on to say that “the principles of democracy, freedom, equality, tolerance and social justice” must be followed “as enunciated by Islam.” Adopted in 1949, the Objectives Resolution marked a huge victory for JUI and other Islamists.

By mid-1952, JUI appeared to be on its way to achieving its objectives. Within months, however, the situation soured. Along with other Islamist groups, it launched a violent nationwide protest movement against the minority Ahmadiyya sect, believing that the move would enhance its political position. In response, the government imposed martial law. A subsequent government inquiry held JUI and the other religious forces responsible for the violence and even questioned the entire premise of the party’s demand for Pakistan to be turned into an Islamic state. Nevertheless, in March 1956, the country’s first constitution came into effect, formally enshrining Pakistan as an Islamic republic. Two and a half years later, however, the military seized power under Gen. Ayub Khan, who was determined to reverse the influence of the Deobandis and the growing broader religious sector. Khan would go on to decree a new constitution that laid the foundations of a secular modern state — one in which the Deobandis did not even achieve their minimalist goal of an advisory role.

The Deobandi movement went through another period of decline and transition during President Khan’s reign. It was in the late 1960s under Mufti Mahmud, a religious scholar-turned-politician from the Pashtun region of Dera Ismail Khan, near the Afghan border that JUI experienced a revival. After Khan allowed political parties to operate again in 1962, Mahmud became JUI’s deputy leader. In truth, though, he was now the real mover and shaker of the Deobandi party steering it towards alliances of convenience with secular parties. Pakistani historian Sayyid A.S. Pirzada, in his 2000 book “The Politics of the Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam Pakistan 1971-1977,” goes into detail on how Mahmud transformed JUI from a religious movement seeking to influence politics into a full-fledged political party participating in electoral politics.

By the time Khan was forced out of office by popular unrest in 1969, socio-economic issues had replaced religion as the driving force shaping Pakistani politics. Another general, Yahya Khan, took over as president and again imposed martial law, abrogating the entire political system his predecessor had put together over an 11-year period. Yahya held general elections in 1970, marking the country’s first free and fair vote. Both secular and left-leaning, the country’s two major parties, the Awami League and Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), came in first and second place in the vote for Parliament with 167 and 86 seats respectively, while JUI won only seven seats.

By now the west-east crisis that had been brewing since the earliest days of Pakistan’s independence was reaching a critical point. The Awami League won all of its seats in East Pakistan while the PPP won all of its seats in the west of the country. The military establishment, meanwhile, refused to transfer power to the Awami League. This caused full-scale public agitation in the east, which quickly turned into a brutal civil war that led to the creation of Bangladesh from what had been East Pakistan.

The war, which killed hundreds of thousands, resulted in two major implications that would help the Deobandis regain much of the political space they had lost since the early 1950s. First, it seriously weakened the military’s role in politics and allowed for the return of civilian rule. Second, it helped JUI and other religious parties to argue that only Islam could bind together different ethnic groups into a singular national fabric.

Within days of the defeat in the December 1971 war, Gen Yahya’s military government came to an end and PPP chief Zulfikar Ali Bhutto became president. In March 1972, JUI chief Mahmud became chief minister of North-Western Frontier Province (NWFP), leading a provincial coalition government with the left-wing Pashtun ethno-nationalist National Awami Party (NAP). The JUI also was a junior partner with NAP in Baluchistan’s provincial government. JUI’s stint in provincial power, however, was cut short when President Bhutto in 1973 dismissed the NAP-JUI cabinet in Baluchistan, accusing it of failing to control an ethno-nationalist insurgency in the province. In protest, the Mahmud-led government in NWFP resigned as well. The Deobandi party then turned its focus to ensuring that the constitution Bhutto’s PPP was crafting would be as much in keeping with its Islamist ideology as was possible.

Well aware that the masses overwhelmingly voted on the basis of bread-and-butter issues as opposed to religion, JUI sought to prevent the ruling and other socialist parties from producing a charter that would seriously limit its share of power. JUI and the country’s broader religious right were able to capitalize on the fact that Bhutto was seeking national consensus for a constitution, which would strengthen a civilian political order led by his ruling PPP. He was thus ready for a quid pro quo with the JUI and other Islamists — conceding on a number of their demands to Islamize the charter in order to establish a parliamentary form of government.

Consequently, Pakistan’s current constitution, which went into effect in August 1973, declared Islam the state religion, made the Objectives Resolution the charter’s preamble, established a Council of Islamic Ideology to ensure all laws were in keeping with the Quran and the Sunnah, and established the criteria of who is a Muslim, among a host of other provisions. The following year the Deobandis and the broader religious right won another major victory in the form of the second amendment, which declared Ahmadis as non-Muslims.

By 1974, the government of PPP founder Zulfikar Ali Bhutto began to appropriate religion into its own politics. Over the next three years, nine parties with JUI in a lead role formed a coalition of Islamist, centrist and leftist factions in the form of the Pakistan National Alliance (PNA) to jointly contest the 1977 elections. The PNA campaign was trying to leverage the demand of the religious right to implement Nizam-i-Mustafa (System of Muhammad).

In an election marred by irregularities, the PPP won 155 seats while the opposition alliance took only 36. After three months of unrest in the wake of the results, Bhutto invited his opponents to negotiate; JUI chief Mahmud led the opposition in the talks. In an effort not to compromise politically, Bhutto sought to appease the Islamists culturally and moved to ban the sale and consumption of liquor, shut all bars, prohibit betting and replace Sunday with the Muslim holy day of Friday as the weekly sabbath. The negotiations were cut short when army chief Gen. Zia mounted a coup, ousting Bhutto and appropriated the Deobandi agenda of Islamization — all designed to roll back the civilianization of the state and restore the military’s role in politics.

Zia’s moves to Islamize society top-down naturally resonated significantly with the religious right. From their point of view, Zia was the very opposite of the country’s first military dictator, Ayub Khan, who had been an existential threat to the entire ulema sector. The Deobandis, however, were caught between their opposition to a military dictatorship and the need to somehow benefit from Zia’s religious agenda. Although he was known for being a religious conservative, Zia was first and foremost a military officer. While the entire raison d’être of the Deobandi JUI was to establish an “Islamic” state, the Zia regime weaponized both the religion of Islam and the ideology of Islamism to gain support for what was essentially a military-dominated political order.

The JUI saw itself as heir to a thousand-year tradition of ulema trying to ensure that Muslim sovereigns in South Asia were ruling in accordance with their faith. Albeit late in the game, it was also a key player in creating Pakistan, and more importantly, worked to ensure that the country’s constitution was Islamic. But now Zia, who had assumed the presidency, had engaged in a hostile takeover of not just the state but the entire Deobandi business model. This explains why Mahmud opposed Zia’s putsch and kept demanding that he stick to his initial pledge of holding elections, which the general kept postponing. Zia’s primary objective was to reverse Bhutto’s efforts to establish civilian supremacy over the military.

By the time Zia banned political parties in October 1979, JUI was struggling to deal with a new autocratic political order that was stealing its thunder. It was also in a state of unprecedented decline. An internal rift had emerged within the party between those opposing Zia’s military regime and those seduced by his Islamization moves. A year later, Mahmud died of a heart attack. Mahmud’s son, a cleric-politician named Fazlur Rehman, was accepted as the new JUI chief by many of the leaders and members of the Deobandi party. But others opposed the hereditary transition. This led to a formal split in the party between Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam — Fazlur Rehman (JUI-F) and Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam Sami-ul-Haq (JUI-S), named after Sami-ul-Haq, a cleric whose madrassah Dar-ul-Uloom Haqqania would soon play a lead role in the rise of militant Deobandism. JUI-F continued to oppose Zia’s martial law regime while the splinter Deobandi faction, JUI-S, became a major supporter of the military government.

The same year that Zia was Islamizing his military regime, three major events shook the Muslim world: the Islamist-led revolution in Iran, the siege of Mecca by a group of messianic Salafists and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. These three developments would prove to be a watershed for the Deobandi movement. Deobandis formed a major component of the Afghan Islamist insurgent alliance fighting the Soviet-backed communist government. Many of the leaders of the Afghan insurgent factions like Mawlawi Yunus Khalis, Mohammed Nabi Mohammedi and Jalaluddin Haqqani were Deobandis. From the early 1980s onward, the two JUI factions were involved in dual projects: supporting the creation of an Islamic state in Afghanistan through armed insurrection and the Islamization of Pakistan (though divided over how on the latter).

At the same time, Saudi Arabia supported the Afghan insurgency and began to step up its promotion of Wahhabism in Pakistan, partly as a response to the Mecca siege. The Deobandis benefited financially and ideologically from Riyadh’s support, leading to the emergence of new groups.

Already wary of how Iran’s clerical regime was exporting its brand of revolutionary Islamism, many Deobandis were influenced by the anti-Shia sectarianism embedded within their own discourse and now energized by proliferating Wahhabism. The Zia regime also had an interest in containing Iranian-inspired revolutionary ideas and supported anti-Shia Deobandi militant factions. In 1985, a group by the name of Sipah-e-Sahabah Pakistan was founded as a militant offshoot of JUI. It would later give way to Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, named after Haq Nawaz Jhangvi, a firebrand anti-Shia Deobandi cleric. Lashkar-e-Jhangvi remains notorious for horrific attacks targeting Pakistan’s Shia minority.

After a century of being a religious-political movement, in the 1980s Deobandism was increasingly militant. The anti-communist insurgency in Afghanistan and sectarian militancy in Pakistan were the two primary drivers increasingly steering many Deobandis toward armed insurrection. While the end of the Zia regime (with the dictator’s death in a plane crash in the summer of 1988) brought back civilian rule to the country, Deobandism was hurtling toward a violent trajectory.

By the early 1990s the Pakistani military had retreated to influencing politics from behind the scenes and no longer pursued a domestic Islamization program. The die, however, had been cast. The extremist forces that Zia had unleashed were now on autopilot, and his civilian and military successors were unable to rein in their growth. Deobandi seminaries continued to proliferate in the country, especially in the Pashtun-dominated areas of the northwest.

In 1993, another militant Deobandi faction demanding the imposition of sharia law emerged in country’s northwest by the name of Tehrik-i-Nifaz-i-Shariat-i-Muhammadi (Movement to Implement the Shariah of Muhammad) — or TNSM — led by Sufi Muhammad, a mullah who had studied at the Panjpir seminary, which was unique in that its Deobandism was heavily Salafized.

The decade long war in Afghanistan against the Soviets had significantly affected the Pakistani military and the country’s premier spy service, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) directorate, which was managing the Afghan, Pakistani and other Arab/Muslim foreign fighters. Many ISI officers had gone native with the militant Deobandi and Salafist ideologies of the proxies that they were managing. By the dawn of the 1990s two unexpected geopolitical developments would accelerate the course of Deobandism toward militancy. First was the December 1991 implosion of the Soviet Union, which a few months later triggered the collapse of the Afghan communist regime. That in turn led to the 1992-96 intra-Islamist war in Afghanistan, which gave rise to the Taliban movement and its first emirate regime. Second was a popular Muslim separatist uprising that began in Indian-administered Kashmir in 1989. The Pakistani military’s efforts to leverage both developments exponentially contributed to the surge of radicalized and militarized Deobandism.

In Afghanistan, Pakistan supported the Taliban, a movement founded by militant Deobandi clerics and students. The military also deployed Islamist insurgent groups in Indian-administered Kashmir, many of which were ideologically Deobandi. They included Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, Harakat-ul-Ansar and Jaish-e-Mohammed. Toward the late 1990s, when the Taliban were in power in Kabul and hosting al Qaeda, these groups constituted a singular transnational ideological battle space stretched from Afghanistan through India. This was most evident after militants hijacked an Indian Airlines flight from Nepal and landed in Taliban-controlled Kandahar. There, the hijackers, enabled by the Pakistani-backed Taliban regime, negotiated with the Indian government for the release of Jaish-e-Mohammed founder Masood Azhar and two of his associates who had been imprisoned for terrorist activities in Kashmir.

After 9/11, the Pakistani security establishment lost control of its militant Deobandi nexus, which gravitated heavily toward al Qaeda that had itself relocated to Pakistan. The U.S. toppling of the Taliban regime forced Islamabad into a situation in which it was trying to balance support for both Washington and the Afghan Taliban. Meanwhile, just days before the U.S. began its military operations against the Taliban in October 2001, Jaish-e-Muhammad operatives attacked the state legislature in Indian-administered Kashmir. This was followed by an even more brazen attack on the Indian Parliament in New Delhi on Dec. 13. The Pakistanis were now under pressure from both the Americans and the Indians. As a result, Islamabad clamped down on the Kashmiri militant outfits. The decision of Pakistan’s then military ruler Gen. Pervez Musharraf to first side with the U.S. against the Taliban and then undertake an unprecedented normalization process with India led to Islamabad losing control over the Deobandi militant landscape. In fact, many of these groups would turn against the Pakistani state itself. There were several assassination attempts on Musharraf, including two back-to-back attacks carried out by rogue military officers within two weeks in December 2003. The radicalized Deobandis whom Pakistan cultivated as instruments of foreign policy in the ’80s and ’90s inverted the vector of jihad to target the very state that nurtured them.

Meanwhile, the country’s main Deobandi political group, JUI-F, remained a force. In the 2002 elections, it led an alliance of six Islamist parties called the Mutahiddah Majlis-i-Amal (United Action Council or MMA) that won 60 seats in Parliament — in great part due to the electoral engineering of the country’s fourth military regime. It also secured the most seats in the provincial legislatures in the old Deobandi stronghold of NWFP, forming a majority government there and a coalition government with the pro-Musharraf ruling party in Baluchistan. The Deobandi-led MMA governments in both western provinces enabled the rise of Talibanization in the Pashtun-regions along the border with Afghanistan. By the time the MMA government in the northwest completed its five-year term in late 2007, some 13 separate Pakistani Taliban factions had come together to form an insurgent alliance known as the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). The Deobandi-led government turned a blind eye to rising Talibanization, partly because it did not want to be seen as siding with the U.S. against fellow Islamists and partly because it feared being targeted by the jihadists. The latter fear was not unfounded given TTP’s several attempts to assassinate several JUI leaders including chief Fazlur Rehman and its Baluchistan supremo Muhammad Khan Sherani.

Militant Deobandism in the form of insurgents controlling territory and engaging in terrorist attacks all over the country would dominate the better part of the next decade. Taliban rebels seized control of large swaths of territory close to the Afghan border. The biggest example of this was the Taliban faction led by Mullah Fazlullah (the son-in-law of the TNSM founder), which took over NWFP’s large Swat district (as well as many parts of adjacent districts).

The Taliban had significant support even in the country’s capital as illustrated by the 2007 siege of the Red Mosque (Islamabad’s oldest and major house of worship). A group of militants led by the mosque’s Deobandi imam and his brother for nearly 18 months had been challenging the writ of the state in the country’s capital by engaging in violent protests, attacks on government property, kidnapping, arson and armed clashes with law enforcement agencies. An 8-day standoff came to an end when army special forces stormed the mosque-seminary complex leading to a 96-hour gun battle with well-armed and trained militants during which at least 150 people (including many women and children) were killed.

The TTP greatly leveraged popular anger over the military operation against the mosque. It unleashed a barrage of suicide bombings targeting high-security military installations including an air weapons complex, a naval station, three regional headquarters of the ISI, special forces headquarters, the army’s general headquarters, the military’s main industrial complex and many other civilian targets, which resulted in tens of thousands of deaths. It took nearly a decade of massive counterinsurgency and counterterrorism operations to claw back provincial and tribal territories that had fallen under TTP control. By the late 2010s, Pakistan’s security forces had forced Taliban rebels to relocate across the border in Afghanistan where the U.S., after 15 years of unsuccessfully trying to weaken the Afghan Taliban movement, was in talks with it.

Washington had hoped that its 2020 peace agreement with the Afghan Taliban would lead to a political process that could limit the jihadist movement’s influence after the U.S. departure. The dramatic collapse of the Afghan government in a little over a week in early August of this year, however, has left the Afghan Taliban as the only group capable of imposing its will on the country. The return of the Afghan Taliban to power in Afghanistan has a strong potential to energize like-minded forces in Pakistan, especially with the Islamic State having a significant cross-border presence and trying to assume the jihadist mantle from the Taliban. Further in the easterly direction, rising right-wing Hindu extremism in India empowered by the current government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi risks radicalizing Deobandism in its country of birth, in response to the targeting of the country’s 200 million Muslim minority.

The Deobandis began in India as a movement seeking to reestablish a Muslim religio-political order in South Asia — one led by ulema. After 80 years of cultivating a religious intellectual vanguard and aligning with the majority Hindu community in secular nationalist politics to achieve independence from British colonial rule, a major chunk of Deoband embraced Muslim separatism. Once that goal was realized in the form of the independent nation-state of Pakistan, the locus of Deobandism shifted to Islamizing the new Muslim polity. For the next three decades, the Deobandis tried to turn a state that was intended to be secular into an Islamic republic through constitutional and electoral processes. The ascent of an Islamist-leaning military regime coupled with regional geopolitics at the tail end of the Cold War fragmented and militarized the Deobandi phenomenon whose locus yet again shifted westward. After the 1980s, the movement increasingly reverted to its British-era jihadist roots through terrorism and insurgency. That process has culminated in the Taliban’s empowerment in Afghanistan and now threatens to destabilize the entire South Asian region.

Today, Afghanistan represents the center of gravity of South Asia’s most prominent form of Islamism. The movement that has long sought to establish an “Islamic” state led by ulema subscribing to a medieval understanding of religion has established the polity that its ideological forefathers had set out to achieve over a century and a half ago.

As the Taliban consolidate their hold over Kabul with dangerous implications for the entire South Asian region, my mind wanders back 40 years to when my father — driven by his own sectarian persuasions — first made me aware of Deobandism. I am amazed at just how rapidly this phenomenon has grown before my eyes. Suffering from dementia for almost a decade and a half, my father has been oblivious of this proliferation. I actually don’t remember the last time either he or I broached this topic with the other. Perhaps it is for the best that he is unaware of the extent to which those whom he opposed all his life have gained ground. I know it would pain him to learn that Deobandism has even contaminated his own Barelvi sect, as is evident from the rise of the Tehrik-i-Labbaik Pakistan, which is now the latest and perhaps most potent Islamist extremist specter to haunt the country of his and my birth.

Sunday, 29 August 2021

Thursday, 19 August 2021

No surprise Leeds lost to Manchester United, just look at the wage bills

Jonathan Wilson in The Guardian

The easy thing is to blame the manager. It has become football’s default response to any crisis. A team hits a poor run or loses a big game: get rid of the manager. As Alex Ferguson said as many as 14 years ago, we live in “a mocking culture” and reality television has fostered the idea people should be voted off with great regularity (that he was trying to defend Steve McClaren’s reign as England manager should not undermine the wider point).

Managers are expendable. Rejigging squads takes time and money and huge amounts of effort in terms of research and recruitment, whereas anybody can look at who is doing well in Portugal or Greece or the Championship and spy a potential messiah. Then there are the structural factors, the underlying economic issues it is often preferable to ignore because to acknowledge them is to accept how little agency the people we shout about every week really have in football.

That point reared its head after Manchester United’s 5-1 victory over Leeds on Saturday. There was plenty to discuss: are Leeds overreliant on Kalvin Phillips, who was absent? Why does Marcelo Bielsa’s version of pressing so often lead to heavy defeats? Can Mason Greenwood’s movement allow Ole Gunnar Solskjær to field Paul Pogba and Bruno Fernandes without sacrificing a holding midfielder and, if it does, what does that mean for Marcus Rashford?

Yet there was a weird strand of coverage that insisted Solskjær had somehow outwitted Bielsa, even in some quarters that Bielsa needed to be replaced if Leeds are to kick on. (They finished ninth last season with 59 points, the highest points total by a promoted club for two decades). A Bielsa meltdown is possible; they do happen and he has never managed a fourth season at a club. There should be some concern that, like last season, Leeds lost by four goals at Old Trafford, insufficient lessons were learned, even if Bielsa said this was a better performance. But fundamentally, Manchester United’s wage bill is five times that of Leeds.

Everton, who finished a place below Leeds last season, had a wage bill three times bigger. Of last season’s Premier League, only West Brom and Sheffield United had wage bills lower than that of Leeds. To have finished ninth is an extraordinary achievement and nobody should think to slip back three or four places this season would be a failure. Modern football is starkly stratified and although teams can often defy financial logic for a time, to move up a tier is incredibly difficult.

There is still a tendency to talk of a Big Six in English football and while it is true six clubs last season had a weekly wage bill in excess of £2.5m, it is also true that within that grouping there are three with clear advantages: Manchester City (who had kept their wage bill relatively low, although if they do add Harry Kane to Jack Grealish that would clearly change) and Chelsea because their funding is not reliant on footballing success, and Manchester United because of the legacy that has allowed them to attach their name to a preposterous range of products across the globe.

Mikel Arteta is struggling to revive Arsenal. Photograph: Tom Jenkins/The Guardian

Mikel Arteta is struggling to revive Arsenal. Photograph: Tom Jenkins/The GuardianLiverpool can perhaps challenge for the title this season, but their wage spending is 74% of that of United. That they were as good as they were in the two seasons before last was remarkable, but last season showed how vulnerable a team like Liverpool can be to a couple of injuries. Similarly, Leicester’s two fifth-place finishes with the eighth-highest wage bill are a striking achievement, their decline towards the end of the past two seasons less the result of them bottling it or any sort of psychological failure than of the limitations of their squad being exposed.

Which brings us to the other two members of the Big Six: Arsenal and Tottenham. Spurs’ last game at White Hart Lane, in 2017, brought a 2-1 win over Manchester United that guaranteed they finished second. Since when Spurs have bought Davinson Sánchez, Lucas Moura, Serge Aurier, Fernando Llorente, Juan Foyth, Tanguy Ndombele, Steven Bergwijn, Ryan Sessegnon, Giovani Lo Celso, Cristian Romero and Bryan Gil, while United have bought, among others, Alexis Sánchez, Victor Lindelöf, Nemanja Matic, Romelu Lukaku, Fred, Daniel James, Aaron Wan-Bissaka, Bruno Fernandes, Harry Maguire, Donny van de Beek, Raphaël Varane and Jadon Sancho. Money may not be everything in football, but it does help.

The irony of the situation is that it was investment in the infrastructure that should allow Spurs to generate additional revenues and better develop their own talent (much cheaper than buying it) that led to the lack of investment in players largely responsible for the staleness resulting in Mauricio Pochettino’s departure. That Daniel Levy compounded the problem by appointing José Mourinho – acting like a big club as though to jolt them to the next level – should not obscure the fact that until that point he had pursued a ruthless and successful economic logic.

Arsenal had gone through a similar process the previous decade, investing heavily in a new stadium at the expense of the squad, only to discover that by the time it was ready the financial environment had changed and the petro-fuelled era had begun. It was easy after the timid performance against Brentford on Friday to blame Mikel Arteta and ask why he gets such an easy ride. For all that Arsenal have finished the past two seasons relatively well, that criticism will only increase if there are not signs the tanker is being turned round. But the gulf to the top of the table is vast and a desperation to bridge that has contributed to a bizarre transfer policy.

That does not mean managers are beyond reproach and limp displays like Arsenal’s deserve criticism. But equally we should probably remember that where a side finishes in the league has far more to do with economic strata than any of the individuals involved.

Monday, 19 July 2021

Thursday, 3 June 2021

Thursday, 13 May 2021

Thursday, 29 April 2021

Saturday, 30 January 2021

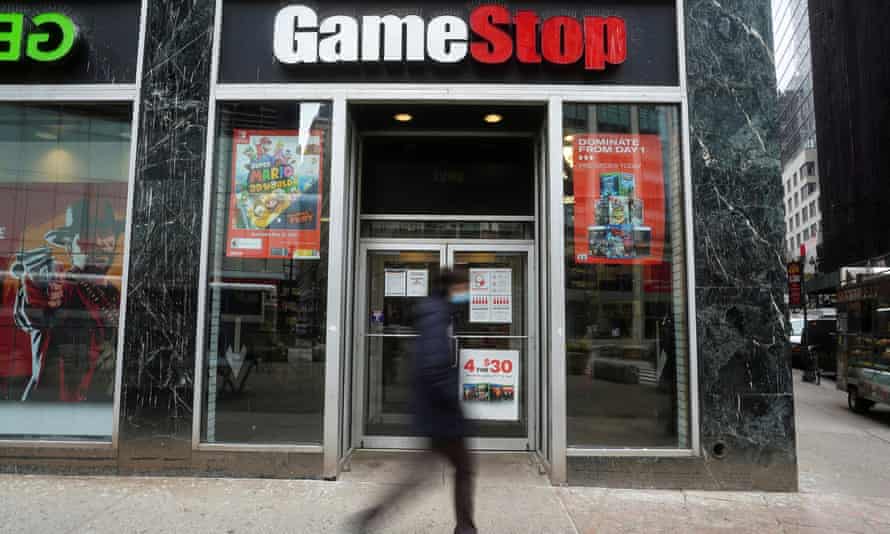

The GameStop affair is like tulip mania on steroids

Towards the end of 1636, there was an outbreak of bubonic plague in the Netherlands. The concept of a lockdown was not really established at the time, but merchant trade slowed to a trickle. Idle young men in the town of Haarlem gathered in taverns, and looked for amusement in one of the few commodities still trading – contracts for the delivery of flower bulbs the following spring. What ensued is often regarded as the first financial bubble in recorded history – the “tulip mania”.

Nearly 400 years later, something similar has happened in the US stock market. This week, the share price of a company called GameStop – an unexceptional retailer that appears to have been surprised and confused by the whole episode – became the battleground between some of the biggest names in finance and a few hundred bored (mostly) bros exchanging messages on the WallStreetBets forum, part of the sprawling discussion site Reddit.

The rubble is still bouncing in this particular episode, but the broad shape of what’s happened is not unfamiliar. Reasoning that a business model based on selling video game DVDs through shopping malls might not have very bright prospects, several of New York’s finest hedge funds bet against GameStop’s share price. The Reddit crowd appears to have decided that this was unfair and that they should fight back on behalf of gamers. They took the opposite side of the trade and pushed the price up, using derivatives and brokerage credit in surprisingly sophisticated ways to maximise their firepower.

To everyone’s surprise, the crowd won; the hedge funds’ risk management processes kicked in, and they were forced to buy back their negative positions, pushing the price even higher. But the stock exchanges have always frowned on this sort of concerted action, and on the use of leverage to manipulate the market. The sheer volume of orders had also grown well beyond the capacity of the small, fee-free brokerages favoured by the WallStreetBets crowd. Credit lines were pulled, accounts were frozen and the retail crowd were forced to sell; yesterday the price gave back a large proportion of its gains.

To people who know a lot about stock exchange regulation and securities settlement, this outcome was quite inevitable – it’s part of the reason why things like this don’t happen every day. To a lot of American Redditors, though, it was a surprising introduction to the complexity of financial markets, taking place in circumstances almost perfectly designed to convince them that the system is rigged for the benefit of big money.

Corners, bear raids and squeezes, in the industry jargon, have been around for as long as stock markets – in fact, as British hedge fund legend Paul Marshall points out in his book Ten and a Half Lessons From Experience something very similar happened last year at the start of the coronavirus lockdown, centred on a suddenly unemployed sports bookmaker called Dave Portnoy. But the GameStop affair exhibits some surprising new features.

Most importantly, it was a largely self-organising phenomenon. For most of stock market history, orchestrating a pool of people to manipulate markets has been something only the most skilful could achieve. Some of the finest buildings in New York were erected on the proceeds of this rare talent, before it was made illegal. The idea that such a pool could coalesce so quickly and without any obvious sign of a single controlling mind is brand new and ought to worry us a bit.

And although some of the claims made by contributors to WallStreetBets that they represent the masses aren’t very convincing – although small by hedge fund standards, many of them appear to have five-figure sums to invest – it’s unfamiliar to say the least to see a pool motivated by rage or other emotions as opposed to the straightforward desire to make money. Just as air traffic regulation is based on the assumption that the planes are trying not to crash into one another, financial regulation is based on the assumption that people are trying to make money for themselves, not to destroy it for other people.

When I think about market regulation, I’m always reminded of a saying of Édouard Herriot, the former mayor of Lyon. He said that local government was like an andouillette sausage; it had to stink a little bit of shit, but not too much. Financial markets aren’t video games, they aren’t democratic and small investors aren’t the backbone of capitalism. They’re nasty places with extremely complicated rules, which only work to the extent that the people involved in them trust one another. Speculation is genuinely necessary on a stock market – without it, you could be waiting days for someone to take up your offer when you wanted to buy or sell shares. But it’s a necessary evil, and it needs to be limited. It’s a shame that the Redditors found this out the hard way.

Friday, 23 October 2020

The power of negative thinking

Tim Harford in The FT

For a road sign to be a road sign, it needs to be placed in proximity to traffic. Inevitably, it is only a matter of time before someone drives into the pole. If the pole is sturdy, the results may be fatal.

The 99% Invisible City, a delightful new book about the under-appreciated wonders of good design, explains a solution. The poles that support street furniture are often mounted on a “slip base”, which joins an upper pole to a mostly buried lower pole using easily breakable bolts.

A car does not wrap itself around a slip-based pole; instead, the base gives way quickly. Some slip bases are even set at an angle, launching the upper pole into the air over the vehicle. The sign is easily repaired, since the base itself is undamaged. Isn’t that clever?

There are two elements to the cleverness. One is specific: the detailed design of the slip-base system. But the other, far more general, is a way of thinking which anticipates that things sometimes go wrong and then plans accordingly.

That way of thinking was evidently missing in England’s stuttering test-and-trace system, which, in early October, failed spectacularly. Public Health England revealed that 15,841 positive test results had neither been published nor passed on to contact tracers.

The proximate cause of the problem was reported to be the use of an outdated file format in an Excel spreadsheet. Excel is flexible and any idiot can use it but it is not the right tool for this sort of job. It could fail in several disastrous ways; in this case, the spreadsheet simply ran out of rows to store the data.

But the deeper cause seems to be that nobody with relevant expertise had been invited to consider the failure modes of the system. What if we get hacked? What if someone pastes the wrong formula into the spreadsheet? What if we run out of numbers?

We should all spend more time thinking about the prospect of failure and what we might do about it. It is a useful mental habit but it is neither easy nor enjoyable.

We humans thrive on optimism. Without the capacity to banish worst-case scenarios from our minds, we could hardly live life at all. Who could marry, try for a baby, set up a business or do anything else that matters while obsessing about what might go wrong? It is more pleasant and more natural to hope for the best.

We must be careful, then, when we allow ourselves to stare steadily at the prospect of failure. Stare too long, or with eyes too wide, and we will be so paralysed with anxiety that success, too, becomes impossible.

Care is also needed in the steps we take to prevent disaster. Some precautions cause more trouble than they prevent. Any safety engineer can reel off a list of accidents caused by malfunctioning safety systems: too many backups add complexity and new ways to fail.

My favourite example — described in the excellent book Meltdown by Chris Clearfield and András Tilcsik — was the fiasco at the Academy Awards of 2017, when La La Land was announced as the winner of the Best Picture Oscar that was intended for Moonlight. The mix-up was made possible by the existence of duplicates of each award envelope — a precaution that triggered the catastrophe.