'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label terror. Show all posts

Showing posts with label terror. Show all posts

Monday, 2 March 2020

Wednesday, 11 December 2019

Tuesday, 3 December 2019

Friday, 26 April 2019

Why Sri Lanka attackers' wealthy backgrounds shouldn't surprise us

Recent history shows that people with comfortable lives can easily be drawn towards violent extremism writes Jason Burke in The Guardian

A group of Bangladeshis linked to Islamic State that attacked a bakery favoured by westerners in Dhaka in 2016, killing 20 hostages, share a similar profile to the Sri Lankan bombers. Almost all were from wealthy, highly educated backgrounds.

Isis has claimed Sunday’s bombings – its most lethal attack since its emergence five years ago. The group’s leadership has a rather different composition. Many are religious clerics, or former Ba’ath party officials. But many of the volunteers who travelled to Syria and Iraq from countries such as Egypt or Tunisia were from comfortable backgrounds, too, as were many who travelled from the UK.

Sri Lanka attacks: police hunting 140 Isis suspects, says president

However, on close inspection, many of the terrorists who went to university never finished their degrees. Others earned qualifications from institutions with dubious or limited academic credibility; many British extremists fall into this category.

Mohammed Zahran Hashim, the rural Sri Lankan preacher who is thought to have been the leader of the Easter bombing attackers and was in touch with Isis overseas, had limited wealth and only a rudimentary religious education.

Both al-Qaida and Isis have attracted large numbers of foot soldiers from backgrounds that are marginal in diverse ways. This is true in the Middle East and south Asia, where minor tribal leaders, out of work craftsmen, smugglers, former militia members, minor government officials, and poor farmers’ children sent to free religious schools have all been drawn to Islamic militant ideologies.

In Europe, many of the men who carried out recent terrorist attacks in France and Belgium were petty criminals, living on the economic margins.

Taken together, this teaches us that neither education nor economics can help explain any one individual’s violent activism. The literature on radicalisation that has been produced since 2001 has yet to pinpoint a cause, and few experts think there might be one.

Instead there are many factors that are seen as creating a risk of radicalisation. When they combine, the risk becomes a clear and present danger. Terrorism, abhorrent though it may be, is a social activity. Ideas spread and are reinforced among peers, married couples, old school friends and families. These ideas are simple. They explain complex events, identities and histories through a rudimentary and binary narrative. Neither education nor wealth is proof against them, and nor is poverty or ignorance.

Security forces at the Colombo home of the spice exporter Mohamed Yusuf Ibrahim, whose sons were among the Easter Sunday attackers. Photograph: MA Pushpa Kumara/EPA

When police and soldiers in Sri Lanka set out on the trail of the attackers who killed more than 350 people in a series of bombings on Easter Sunday, they did not expect to find themselves in Dematagoda, one of the wealthiest neighbourhoods in Colombo.

Within 90 minutes of the attack, as hospitals struggled to cope with the huge number of casualties, the security forces were closing in on a three-storey house with a BMW parked outside.

Two brothers lived there with their families: 38-year-old Inshaf Ibrahim, a copper factory owner, and Ilham, 36. Their father, Mohamed Yusuf Ibrahim, one of the most successful businesspeople in the island nation’s Muslim community, made a fortune exporting spices. The two brothers were also involved in the jewellery trade. They were both among the attackers.

When police moved in, there was another blast. It is unclear whether the top floors were wired with explosives or if the elder brother’s wife, Fatima, had set them off. The couple’s three children were instantly killed.

On Thursday, police confirmed that Mohamed Yusuf Ibrahim had been detained.

“They seemed like good people,” a neighbour told reporters from her rundown home opposite the Ibrahim family residence in the capital.

When police and soldiers in Sri Lanka set out on the trail of the attackers who killed more than 350 people in a series of bombings on Easter Sunday, they did not expect to find themselves in Dematagoda, one of the wealthiest neighbourhoods in Colombo.

Within 90 minutes of the attack, as hospitals struggled to cope with the huge number of casualties, the security forces were closing in on a three-storey house with a BMW parked outside.

Two brothers lived there with their families: 38-year-old Inshaf Ibrahim, a copper factory owner, and Ilham, 36. Their father, Mohamed Yusuf Ibrahim, one of the most successful businesspeople in the island nation’s Muslim community, made a fortune exporting spices. The two brothers were also involved in the jewellery trade. They were both among the attackers.

When police moved in, there was another blast. It is unclear whether the top floors were wired with explosives or if the elder brother’s wife, Fatima, had set them off. The couple’s three children were instantly killed.

On Thursday, police confirmed that Mohamed Yusuf Ibrahim had been detained.

“They seemed like good people,” a neighbour told reporters from her rundown home opposite the Ibrahim family residence in the capital.

In an interview with CNN, Sri Lanka’s prime minister, Ranil Wickremesinghe, said the suspected bombers were upper and middle class, and were well educated abroad, a profile he described as “surprising.”

His surprise was widely shared. In the Sri Lanka, the wider region and beyond, many still find it very difficult to understand how those with comfortable lives can be drawn into extremism, and kill themselves and hundreds of innocent people.

The question has been asked many times before. In Europe, it became an issue in the 1970s when relatively well-off young men and women in Germany, Japan, Italy or the US began to engage in violent activism. With the spread of suicide tactics in the 1980s and early 1990s, it seemed more perplexing than ever.

Then came a new wave of Islamic militancy, with attacks of unprecedented lethality. None of the men who flew planes into the World Trade Center in New York in 2001 faced economic hardship. The leader of their organisation, Osama bin Laden, was the son of a construction tycoon.

One of the Easter Sunday bombers attended Kingston University in south-west London from 2006-07, where he studied aeronautical engineering, and then went on to study in Australia. From a wealthy tea trading family based near the central city of Kandy, he had attended top international schools – as had other bombers, it appears.

There are many examples of terrorists with good educational qualifications among Islamic militants. The current leader of al-Qaida, Ayman al-Zawahiri, is a qualified paediatrician, while two-thirds of the 9/11 attackers had degrees. One plot in Britain in 2007 was almost entirely composed by highly qualified medical personnel.

His surprise was widely shared. In the Sri Lanka, the wider region and beyond, many still find it very difficult to understand how those with comfortable lives can be drawn into extremism, and kill themselves and hundreds of innocent people.

The question has been asked many times before. In Europe, it became an issue in the 1970s when relatively well-off young men and women in Germany, Japan, Italy or the US began to engage in violent activism. With the spread of suicide tactics in the 1980s and early 1990s, it seemed more perplexing than ever.

Then came a new wave of Islamic militancy, with attacks of unprecedented lethality. None of the men who flew planes into the World Trade Center in New York in 2001 faced economic hardship. The leader of their organisation, Osama bin Laden, was the son of a construction tycoon.

One of the Easter Sunday bombers attended Kingston University in south-west London from 2006-07, where he studied aeronautical engineering, and then went on to study in Australia. From a wealthy tea trading family based near the central city of Kandy, he had attended top international schools – as had other bombers, it appears.

There are many examples of terrorists with good educational qualifications among Islamic militants. The current leader of al-Qaida, Ayman al-Zawahiri, is a qualified paediatrician, while two-thirds of the 9/11 attackers had degrees. One plot in Britain in 2007 was almost entirely composed by highly qualified medical personnel.

A group of Bangladeshis linked to Islamic State that attacked a bakery favoured by westerners in Dhaka in 2016, killing 20 hostages, share a similar profile to the Sri Lankan bombers. Almost all were from wealthy, highly educated backgrounds.

Isis has claimed Sunday’s bombings – its most lethal attack since its emergence five years ago. The group’s leadership has a rather different composition. Many are religious clerics, or former Ba’ath party officials. But many of the volunteers who travelled to Syria and Iraq from countries such as Egypt or Tunisia were from comfortable backgrounds, too, as were many who travelled from the UK.

Sri Lanka attacks: police hunting 140 Isis suspects, says president

However, on close inspection, many of the terrorists who went to university never finished their degrees. Others earned qualifications from institutions with dubious or limited academic credibility; many British extremists fall into this category.

Mohammed Zahran Hashim, the rural Sri Lankan preacher who is thought to have been the leader of the Easter bombing attackers and was in touch with Isis overseas, had limited wealth and only a rudimentary religious education.

Both al-Qaida and Isis have attracted large numbers of foot soldiers from backgrounds that are marginal in diverse ways. This is true in the Middle East and south Asia, where minor tribal leaders, out of work craftsmen, smugglers, former militia members, minor government officials, and poor farmers’ children sent to free religious schools have all been drawn to Islamic militant ideologies.

In Europe, many of the men who carried out recent terrorist attacks in France and Belgium were petty criminals, living on the economic margins.

Taken together, this teaches us that neither education nor economics can help explain any one individual’s violent activism. The literature on radicalisation that has been produced since 2001 has yet to pinpoint a cause, and few experts think there might be one.

Instead there are many factors that are seen as creating a risk of radicalisation. When they combine, the risk becomes a clear and present danger. Terrorism, abhorrent though it may be, is a social activity. Ideas spread and are reinforced among peers, married couples, old school friends and families. These ideas are simple. They explain complex events, identities and histories through a rudimentary and binary narrative. Neither education nor wealth is proof against them, and nor is poverty or ignorance.

Tuesday, 19 March 2019

Wednesday, 13 March 2019

Friday, 6 October 2017

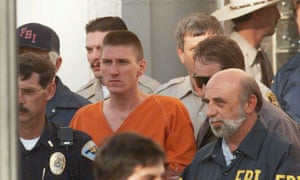

What's a 'lone wolf'? It's the special name we give white terrorists

Moustafa Bayoumi in The Guardian

We have a double standard in the United States when it comes to talking about terrorism. The label is reserved almost exclusively for when we’re talking about Muslims.

Consider Stephen Craig Paddock, the shooter in Sunday’s massacre in Las Vegas. Is he a terrorist? Well, the authorities aren’t calling him one, at least not yet.

This is all the more remarkable because Paddock’s actions clearly fit the statutory definition of terrorism in Nevada. That state’s law defines terrorism as “any act that involves the use or attempted use of sabotage, coercion or violence which is intended to cause great bodily harm or death to the general population”.

Stephen Craig Paddock shot and killed at least 59 people and injured more than 500 others. If that doesn’t qualify as a textbook definition of Nevada’s terrorism law, I don’t know what does.

Yet, when asked at a press conference in Las Vegas if the shooting was an act of terrorism, Clark County Sheriff Joe Lombardo replied: “No. Not at this point. We believe it’s a local individual. He resides here locally,” suggesting that all terrorism is foreign in nature.

Lombardo didn’t call Paddock a terrorist, but he did label him a “lone wolf”, which in our lexicon is that special name we use for “white-guy terrorist”.

Nor is this oversight limited to Lombardo. Las Vegas’s mayor, Carolyn Goodman, also described Paddock not as a terrorist but as “a crazed lunatic, full of hate”. No doubt many other people will repeat the same sentiment in the days to come.

And Donald Trump, who craves every opportunity to utter the words “radical Islamic terrorism”, avoided any mention of the word “terrorist” when discussing the tragic events of Sunday night.

Speaking from the White House, the president instead called the mass shooting “an act of pure evil”. Rather than offering sensible policy changes, such as greater gun control, the president had other ideas. He thinks we should pray more.

Paddock’s act though is, by definition, terrorism. Even under the stricter federal definition of terrorism, Paddock’s murderous rampage should qualify. The federal code defines “domestic terrorism” in part as “activities that appear intended to affect the conduct of government by mass destruction”. It’s hard, if not impossible, to understand how committing one of the largest mass shootings in American history is not “intended to affect the conduct of government”.

But one reason, beyond outright racism, why white people are less frequently charged with terrorism than Muslims in the United States lies with the little-known fact that while federal law does define “domestic terrorism”, it does not codify “domestic terrorism” as a federal crime. (At least 33 states do, however, have anti-terror legislation.) This is partly out of concern that such a statute could go a long way toward criminalizing thought and trampling on the first amendment.

Federal law does contain “hate crime” provisions, but in our present war on terror, it’s one thing to be convicted of “hate” and quite another of “terrorism”. Someone who hates is considered a bad person. Meanwhile, in the eyes of many, someone who is a terrorist doesn’t even deserve to be human.

What this legal reality translates into is a world where the vast majority of the high-profile terrorism prosecutions brought in this country, the ones announced by the justice department with great fanfare and heralding a safer future, basically never revolve around domestic terrorism.

This became clear recently when the attorney general, Jeff Sessions, surprisingly said that the death of Heather Heyer in Charlottesville, Virginia at the hands of a white nationalist sympathizer constituted “domestic terrorism”. But lawyers repeatedly pointed out that at the federal level, domestic terrorism “doesn’t constitute an independent crime or trigger heightened penalties”, according to the website justsecurity.org.

Instead, the high-profile terrorism cases that do trigger heightened penalties are the foreign terrorism cases that almost always involve Muslims, especially since the justice department’s prosecutions of international terrorism is determined by a list of some 60 designated “foreign terrorist organizations”, most of whom are active in Muslim-majority countries. Even material support cases directly related to domestic terrorism are rarely prosecuted in federal court.

A bias, in other words, is embedded in the structure of our laws and how we prosecute them. Foreign terrorism prosecutions put the focus on Muslims and foreign conflicts, while domestic terrorism gets downplayed in our federal courts.

Any predisposition one may have already had that it’s Islam that produces terrorism is thus repeatedly reinforced in who gets prosecuted under our laws. And those attitudes, bolstered by the law, become mainstream in our news media, on our television screens, and in our day-to-day conversations with friends and neighbors.

But in the United States far more people, by orders of magnitude, are killed by gun violence than terrorism carried out in the name of Islam. We just don’t pay attention.

In 2017 alone, there have been 273 mass shootings, about one a day, and 11,671 deaths due to gun violence, according to Gun Violence Archive. Those numbers may surprise you. They did me, and they’re abysmal.

In our society, the federal government often directs the attentions of the people through their policies and priorities. Today, especially under Donald Trump, federal authorities seem even less interested in talking about domestic terrorism.

When a mosque in Minnesota was bombed earlier this year, for example, the White House didn’t even bat an eyelid. Meanwhile, acts like Trump’s Muslim ban reinforce the idea that anyone, anyone at all who comes from one of the barred countries – almost all of whom are Muslim-majority – ought to be considered a security threat.

The answer to this kind of institutionalized and deeply ingrained Islamophobia is to recognize how this clear double standard lets too many domestic terrorism perpetrators off the hook.

We should explain to our government that the interests of justice are served when the terrorism label is fairly and accurately applied.

We should point out to the government that, in their zeal to make the country safe from outsider threats, they are enabling domestic threats to proliferate. And we must hope that this administration in particular will see our warnings as a caution and not as a plan.

We have a double standard in the United States when it comes to talking about terrorism. The label is reserved almost exclusively for when we’re talking about Muslims.

Consider Stephen Craig Paddock, the shooter in Sunday’s massacre in Las Vegas. Is he a terrorist? Well, the authorities aren’t calling him one, at least not yet.

This is all the more remarkable because Paddock’s actions clearly fit the statutory definition of terrorism in Nevada. That state’s law defines terrorism as “any act that involves the use or attempted use of sabotage, coercion or violence which is intended to cause great bodily harm or death to the general population”.

Stephen Craig Paddock shot and killed at least 59 people and injured more than 500 others. If that doesn’t qualify as a textbook definition of Nevada’s terrorism law, I don’t know what does.

Yet, when asked at a press conference in Las Vegas if the shooting was an act of terrorism, Clark County Sheriff Joe Lombardo replied: “No. Not at this point. We believe it’s a local individual. He resides here locally,” suggesting that all terrorism is foreign in nature.

Lombardo didn’t call Paddock a terrorist, but he did label him a “lone wolf”, which in our lexicon is that special name we use for “white-guy terrorist”.

Nor is this oversight limited to Lombardo. Las Vegas’s mayor, Carolyn Goodman, also described Paddock not as a terrorist but as “a crazed lunatic, full of hate”. No doubt many other people will repeat the same sentiment in the days to come.

And Donald Trump, who craves every opportunity to utter the words “radical Islamic terrorism”, avoided any mention of the word “terrorist” when discussing the tragic events of Sunday night.

Speaking from the White House, the president instead called the mass shooting “an act of pure evil”. Rather than offering sensible policy changes, such as greater gun control, the president had other ideas. He thinks we should pray more.

Paddock’s act though is, by definition, terrorism. Even under the stricter federal definition of terrorism, Paddock’s murderous rampage should qualify. The federal code defines “domestic terrorism” in part as “activities that appear intended to affect the conduct of government by mass destruction”. It’s hard, if not impossible, to understand how committing one of the largest mass shootings in American history is not “intended to affect the conduct of government”.

But one reason, beyond outright racism, why white people are less frequently charged with terrorism than Muslims in the United States lies with the little-known fact that while federal law does define “domestic terrorism”, it does not codify “domestic terrorism” as a federal crime. (At least 33 states do, however, have anti-terror legislation.) This is partly out of concern that such a statute could go a long way toward criminalizing thought and trampling on the first amendment.

Federal law does contain “hate crime” provisions, but in our present war on terror, it’s one thing to be convicted of “hate” and quite another of “terrorism”. Someone who hates is considered a bad person. Meanwhile, in the eyes of many, someone who is a terrorist doesn’t even deserve to be human.

What this legal reality translates into is a world where the vast majority of the high-profile terrorism prosecutions brought in this country, the ones announced by the justice department with great fanfare and heralding a safer future, basically never revolve around domestic terrorism.

This became clear recently when the attorney general, Jeff Sessions, surprisingly said that the death of Heather Heyer in Charlottesville, Virginia at the hands of a white nationalist sympathizer constituted “domestic terrorism”. But lawyers repeatedly pointed out that at the federal level, domestic terrorism “doesn’t constitute an independent crime or trigger heightened penalties”, according to the website justsecurity.org.

Instead, the high-profile terrorism cases that do trigger heightened penalties are the foreign terrorism cases that almost always involve Muslims, especially since the justice department’s prosecutions of international terrorism is determined by a list of some 60 designated “foreign terrorist organizations”, most of whom are active in Muslim-majority countries. Even material support cases directly related to domestic terrorism are rarely prosecuted in federal court.

A bias, in other words, is embedded in the structure of our laws and how we prosecute them. Foreign terrorism prosecutions put the focus on Muslims and foreign conflicts, while domestic terrorism gets downplayed in our federal courts.

Any predisposition one may have already had that it’s Islam that produces terrorism is thus repeatedly reinforced in who gets prosecuted under our laws. And those attitudes, bolstered by the law, become mainstream in our news media, on our television screens, and in our day-to-day conversations with friends and neighbors.

But in the United States far more people, by orders of magnitude, are killed by gun violence than terrorism carried out in the name of Islam. We just don’t pay attention.

In 2017 alone, there have been 273 mass shootings, about one a day, and 11,671 deaths due to gun violence, according to Gun Violence Archive. Those numbers may surprise you. They did me, and they’re abysmal.

In our society, the federal government often directs the attentions of the people through their policies and priorities. Today, especially under Donald Trump, federal authorities seem even less interested in talking about domestic terrorism.

When a mosque in Minnesota was bombed earlier this year, for example, the White House didn’t even bat an eyelid. Meanwhile, acts like Trump’s Muslim ban reinforce the idea that anyone, anyone at all who comes from one of the barred countries – almost all of whom are Muslim-majority – ought to be considered a security threat.

The answer to this kind of institutionalized and deeply ingrained Islamophobia is to recognize how this clear double standard lets too many domestic terrorism perpetrators off the hook.

We should explain to our government that the interests of justice are served when the terrorism label is fairly and accurately applied.

We should point out to the government that, in their zeal to make the country safe from outsider threats, they are enabling domestic threats to proliferate. And we must hope that this administration in particular will see our warnings as a caution and not as a plan.

Monday, 21 August 2017

Extremism is surging. To beat it, we need young hearts and minds

Scott Atran in The Guardian

The last of the shellshocked were being evacuated as I headed back toward Las Ramblas, Barcelona’s famed tourist-filled walkway where another disgruntled “soldier of Islamic State” had ploughed a van into the crowd, killing at least 13 and injuring more than 120 from 34 nations. Minutes before the attack I had dropped my wife’s niece near where the rampage began. It was deja vu and dread again, as with the Paris massacre at the Bataclan theatre in 2015, next door to where my daughter lived.

At a seafront promenade south of Barcelona, a car of five knife-wielding kamikaze mowed down a woman before police killed them all. One teenage attacker had posted on the web two years before that “on my first day as king of the world” he would “kill the unbelievers and leave only Muslims who follow their religion”.

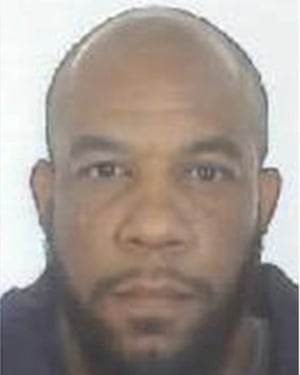

Mariano Rajoy, the president of Spain, declared that “our values and way of life will triumph” – just as Theresa May had proclaimed “our values will prevail” in March when yet another petty criminal “born again” into radical Islam drove his vehicle across Westminster Bridge to kill and wound pedestrians.

In Charlottesville the week before, the white supremacist attacker who killed civil rights activist Heather Heyer mimicked Isis-inspired killings using vehicles. “This was something that was growing in him,” the alleged attacker’s former history teacher told a newspaper. “He had this fascination with nazism [and] white supremacist views … I admit I failed. But this is definitely a teachable moment and something we need to be vigilant about, because this stuff is tearing up our country.”

The values of liberal and open democracy increasingly appear to be losing ground around the world to those of narrow, xenophobic ethno-nationalisms and radical Islam. This is not a “clash of civilisations”, but a collapse of communities, for ethno-nationalist violent extremism and transnational jihadi terrorism represent not the resurgence of traditional cultures, but their unravelling.

This is the dark side of globalisation. The western nation-state and relatively open markets that dominate the global political and economic order have largely supplanted age-old forms of governance and social life. People across the planet have been transformed into competitive players seeking fulfilment through material accumulation and its symbols. But the forced participation and gamble in the rush of market-driven change often fails, especially among communities that have had little time to adapt. When it does, redemptive violence is prone to erupt.

The quest for elimination of uncertainty, coupled with what social psychologist Arie Kruglanski deems “the search for significance”, are the personal sentiments most readily elicited in my research team’s interviews with violent jihadists and militant supporters of populist ethno-nationalist movements. In Hungary, we find strong support for the government’s call for restoring the “national cohesion” lost with the fall of Miklós Hothy’s fascist regime in the second world war. In Iraq, we find nearly all young people coming out from under Isis rule in Mosul initially welcomed the stability and security it offered, despite its brutality, amid the chaos following the US invasion.

In the world of liberal democracy and human rights, violence – especially extreme forms of mass bloodshed – is generally considered pathological or an evil expression of human nature. But across most history and cultures, violence against other groups is claimed by the perpetrators to be a sublime matter of moral virtue. For without a claim to virtue it is difficult, if not inconceivable, to kill large numbers of people innocent of direct harm to others.

Ever since the second world war, revolutionaries and insurgents willing to sacrifice themselves for causes and groups have prevailed with considerably less firepower and manpower than the state armies and police forces they oppose. Meanwhile, according to the World Values Survey, the majority of Europeans don’t believe democracy is “absolutely important” for them; and in France and Spain we find little evidence of willingness to sacrifice much of anything for democracy – in contrast to the willingness to fight and die among supporters of militant jihad.

How can we resist, compete with, and overcome these strengthening countercultural pressures in the present age? Perhaps, for some, a re-enchantment and communitarian rerooting of our own values of representative government and cultural tolerance provides an answer. Preserving what is left of the planet’s fauna and flora and avoiding environmental catastrophes may offer a new course for others. Or the coming generation, if allowed, may offer whole new ways of understanding.

Young people are viewed mostly as a youth bulge and a problem to be pummelled rather than as a youth boom

Yet no countervailing message will spread in a social vacuum, in the abstract space of ideology or counter-narrative alone. The means of engagement are critical, requiring close knowledge of communities at risk. Most often, people join radical groups through pre-existing social networks. This clustering suggests that much recruitment does not take place primarily via direct appeals or following individual exposure to social media (which would entail a more dispersed recruitment pattern). Rather, recruiting often involves enlisting clusters of family, friends and fellow travellers from specific locales (neighbourhoods, universities, prisons).

Our research into the history of Isis-inspired attacks in western Europe clearly indicates that initial attempts by those directly commissioned by Islamic State, and without involvement from locally pre-existing social networks, mostly failed; however, as that involvement broadened and deepened, attacks became progressively more lethal. In our research, we find loose but wide-ranging connections between jihadist circles in Barcelona and much of western Europe, the Maghreb, the Levant and beyond that stretch back even before the attacks of 9/11.

The necessary focus of engagement must be youth, who form the bulk of today’s radical recruits and tomorrow’s most vulnerable populations. Volunteers for al-Qaida, Isis and many extreme nationalist groups are often young people in transitional stages in their lives – immigrants, students, people between jobs and before finding their life partners. Having left their homes and parents, they seek new families of friends and fellow travellers to find purpose and significance.

We need a strategy to redirect radicalised youth by engaging with their passions, rather than ignoring or fearing them, or satisfying ourselves by calling on others to moderate or simply denounce them. Of course there are limits to tolerance, and dangers of worse violence in appeasement of the intolerable. Our partisan divisions include real differences in values that politicians and pundits hype and ply into existential threats. But there are still vast common grounds in a world where all but the too-far-gone can live life with more than a minimum of liberty and happiness, if given half a chance. It is for this chance that some of our forebears fought revolutions, civil wars and world wars.

The last of the shellshocked were being evacuated as I headed back toward Las Ramblas, Barcelona’s famed tourist-filled walkway where another disgruntled “soldier of Islamic State” had ploughed a van into the crowd, killing at least 13 and injuring more than 120 from 34 nations. Minutes before the attack I had dropped my wife’s niece near where the rampage began. It was deja vu and dread again, as with the Paris massacre at the Bataclan theatre in 2015, next door to where my daughter lived.

At a seafront promenade south of Barcelona, a car of five knife-wielding kamikaze mowed down a woman before police killed them all. One teenage attacker had posted on the web two years before that “on my first day as king of the world” he would “kill the unbelievers and leave only Muslims who follow their religion”.

Mariano Rajoy, the president of Spain, declared that “our values and way of life will triumph” – just as Theresa May had proclaimed “our values will prevail” in March when yet another petty criminal “born again” into radical Islam drove his vehicle across Westminster Bridge to kill and wound pedestrians.

In Charlottesville the week before, the white supremacist attacker who killed civil rights activist Heather Heyer mimicked Isis-inspired killings using vehicles. “This was something that was growing in him,” the alleged attacker’s former history teacher told a newspaper. “He had this fascination with nazism [and] white supremacist views … I admit I failed. But this is definitely a teachable moment and something we need to be vigilant about, because this stuff is tearing up our country.”

The values of liberal and open democracy increasingly appear to be losing ground around the world to those of narrow, xenophobic ethno-nationalisms and radical Islam. This is not a “clash of civilisations”, but a collapse of communities, for ethno-nationalist violent extremism and transnational jihadi terrorism represent not the resurgence of traditional cultures, but their unravelling.

This is the dark side of globalisation. The western nation-state and relatively open markets that dominate the global political and economic order have largely supplanted age-old forms of governance and social life. People across the planet have been transformed into competitive players seeking fulfilment through material accumulation and its symbols. But the forced participation and gamble in the rush of market-driven change often fails, especially among communities that have had little time to adapt. When it does, redemptive violence is prone to erupt.

The quest for elimination of uncertainty, coupled with what social psychologist Arie Kruglanski deems “the search for significance”, are the personal sentiments most readily elicited in my research team’s interviews with violent jihadists and militant supporters of populist ethno-nationalist movements. In Hungary, we find strong support for the government’s call for restoring the “national cohesion” lost with the fall of Miklós Hothy’s fascist regime in the second world war. In Iraq, we find nearly all young people coming out from under Isis rule in Mosul initially welcomed the stability and security it offered, despite its brutality, amid the chaos following the US invasion.

In the world of liberal democracy and human rights, violence – especially extreme forms of mass bloodshed – is generally considered pathological or an evil expression of human nature. But across most history and cultures, violence against other groups is claimed by the perpetrators to be a sublime matter of moral virtue. For without a claim to virtue it is difficult, if not inconceivable, to kill large numbers of people innocent of direct harm to others.

Ever since the second world war, revolutionaries and insurgents willing to sacrifice themselves for causes and groups have prevailed with considerably less firepower and manpower than the state armies and police forces they oppose. Meanwhile, according to the World Values Survey, the majority of Europeans don’t believe democracy is “absolutely important” for them; and in France and Spain we find little evidence of willingness to sacrifice much of anything for democracy – in contrast to the willingness to fight and die among supporters of militant jihad.

How can we resist, compete with, and overcome these strengthening countercultural pressures in the present age? Perhaps, for some, a re-enchantment and communitarian rerooting of our own values of representative government and cultural tolerance provides an answer. Preserving what is left of the planet’s fauna and flora and avoiding environmental catastrophes may offer a new course for others. Or the coming generation, if allowed, may offer whole new ways of understanding.

Young people are viewed mostly as a youth bulge and a problem to be pummelled rather than as a youth boom

Yet no countervailing message will spread in a social vacuum, in the abstract space of ideology or counter-narrative alone. The means of engagement are critical, requiring close knowledge of communities at risk. Most often, people join radical groups through pre-existing social networks. This clustering suggests that much recruitment does not take place primarily via direct appeals or following individual exposure to social media (which would entail a more dispersed recruitment pattern). Rather, recruiting often involves enlisting clusters of family, friends and fellow travellers from specific locales (neighbourhoods, universities, prisons).

Our research into the history of Isis-inspired attacks in western Europe clearly indicates that initial attempts by those directly commissioned by Islamic State, and without involvement from locally pre-existing social networks, mostly failed; however, as that involvement broadened and deepened, attacks became progressively more lethal. In our research, we find loose but wide-ranging connections between jihadist circles in Barcelona and much of western Europe, the Maghreb, the Levant and beyond that stretch back even before the attacks of 9/11.

The necessary focus of engagement must be youth, who form the bulk of today’s radical recruits and tomorrow’s most vulnerable populations. Volunteers for al-Qaida, Isis and many extreme nationalist groups are often young people in transitional stages in their lives – immigrants, students, people between jobs and before finding their life partners. Having left their homes and parents, they seek new families of friends and fellow travellers to find purpose and significance.

We need a strategy to redirect radicalised youth by engaging with their passions, rather than ignoring or fearing them, or satisfying ourselves by calling on others to moderate or simply denounce them. Of course there are limits to tolerance, and dangers of worse violence in appeasement of the intolerable. Our partisan divisions include real differences in values that politicians and pundits hype and ply into existential threats. But there are still vast common grounds in a world where all but the too-far-gone can live life with more than a minimum of liberty and happiness, if given half a chance. It is for this chance that some of our forebears fought revolutions, civil wars and world wars.

Friday, 2 June 2017

Writing fiction is a prayer, a song: Arundhati Roy

Zac O'Yeah in The Hindu

Arundhati Roy opens her door and lets me in – into her kitchen. I wonder if I’ve knocked on the wrong door: the delivery entrance, perhaps? I quickly hand over the humble gift of fresh coffee beans I’ve brought her, on the assumption that all serious writers love coffee.

As we sit down around her solid wood kitchen table surrounded by funky chairs, I realize that the kitchen is the warm heart of her self-designed apartment in central New Delhi. Apart from long work counters, there’s a sofa, a bookshelf, a sit-out terrace with an antique-looking bench – altogether a place where one could spend a lifetime.

But right now she’s all over the world and is somewhat jet-lagged after having just flown in from New York. Following a bunch of interviews in town, she’s soon off again on a worldwide promotion tour for her new novel. The Ministry of Utmost Happiness is her first in two decades since the globally bestselling, Booker Prize-winning, The God of Small Things. It appears to be the literary happening of the decade and according to her publishers ‘it reinvents what a novel can do and can be’. I’ve started reading it and can say that it is a ruthlessly probing and wide-ranging narrative on contemporary India, written with a linguistic felicity that reminds me of Salman Rushdie’s classic Midnight’s Children. On the whole, it makes interviewing her an intimidating prospect. While she makes coffee, I rig up my electronic defences consisting of three audio recorders (two of which conk out during the interview) and a backup video camera. She looks on bemusedly and seems used to a barrage of microphones. We embark on a three-hour interview session. Excerpts:

Generations of new Indian writers have seen you as an inspiration, as someone who allowed them to dream that one could sit in India and write and then be read all over the world. How does your iconic status feel to you? Do you ever think about it?

Not really, because I am equally balanced by the kind of rage and craziness that I evoke. For me, I live inside my work. Although I must say that I was thinking at some time about writers who like to remain anonymous – but I’ve never been that person. Because, in this country it is important, especially as a woman, to say: “Hey! Here I am! I am going to take you on! And this is what I think and I’m not going to hide.” So if I have helped to give courage to anybody… to experiment… to step out of line… That’s lovely, I think it is very important for us to say: “We can! And we will! And don’t f*** with us!” You know, come on.

I’ve noticed that you don’t often appear at literary festivals. There are more than a hundred in India these days, and I’ve been to quite a few myself, but never met you before. Do you keep away from other writers?

It’s not about other writers. I don’t know if you’ve read this essay I wrote called Capitalism – A Ghost Story and Walking with the Comrades? The thing is that the Jaipur Literature Festival is funded by a kind of notorious mining company that is silencing the voices of the Adivasis, kicking them out of their homes, and now it is also funded by Zee TV which is half the time baying for my blood. So in principle I won’t go. How can I? I’m writing against them. I mean, it’s not that I’m a pure person, like all of us I have contradictions and issues, I’m not like Gandhiji, you know, but in theory I abide by this. How can you be silencing and snuffing out the voices of the poorest people in the world, and then become this glittering platform for free speech and flying writers all around the place? I have a problem with that.

Do you read a lot of new Indian fiction or non-fiction?

When I’ve been writing this book, I haven’t been very up on current things. I’m not even on Facebook and all that. I don’t have any problem [with it], but as Edward Snowden told me, the CIA celebrated when Facebook was started, because they just got all the information without having to collect it. That aside, I think that when you’re writing, you tend to be a bit strange about reading: sometimes I’m not reading whole books, I’m dipping into things to check my own sanity. ’ (She waves her left hand in a kind of elegantly psychedelic mudra before her face.) ‘Am I on the same planet?

Is there any particular Indian writer who you admire?

I think that Naipaul is a very accomplished writer, although we are worlds apart in our worldviews. But I’m not really that influenced by anybody, you know. I have to say that I find it incredible that writers in India, or almost all Indian writers, or at least the well-known writers… Let’s not say writers, but there’s been a level of eliding of things that have been at the heart of the society, like caste. You see there is something very wrong here. It is like people in apartheid South Africa writing without mentioning that there is apartheid.

Your writing is hard-hitting and outspoken – have you experienced any adverse repercussions?

My God, that’s to put it mildly. Other than of course going to jail and all that. Even now, when the last book of essays was released in Delhi, called Broken Republic, a gang of vigilantes came on stage, smashed the stage up. The right wing, the mobs, vigilantes, they are there at every meeting, threatening violence, threatening all kinds of things. I still go to speak, to Punjab, in Orissa, wherever, I’m not really that writer who is sequestered somewhere and I live perhaps alone, but in the heart of the crowd.

It must have been a bit of a shock, after expressing a personal opinion, to suddenly find yourself behind bars in Tihar Jail?

Tihar. (She sighs deeply.) Yes, it is shocking, but at the same time look at how many thousands of people are behind bars, people who have no understanding of the language, who don’t even know what they’re charged with. So I can’t really be dramatic about what happened to me, because people are in jail for years for nothing – nothing! It’s crazy! I’m currently being tried for contempt of court again for an essay I wrote called Professor P.O.W. which you can read in Outlook Magazine.

Have you ever felt that you should leave India and live in a country where you don’t have to face such problems?

Everything that I know is here! Everyone that I know! And I’ve never really lived outside, abroad, so the idea of going to live all alone in some strange country is also terrifying. But right now I think India is poised in an extremely dangerous place, I don’t know what is going to happen to anybody – to me or to anybody. There are just these mobs that decide who should be killed, who should be shot, who should be lynched, you know? I think it is probably the first time that people in India, writers and other people, are facing the kind of trauma that people have faced in Chile and Latin America. There’s a kind of terror building up here which we have not fully got the measure of. You go through periods when you are feeling very worried, then angry, and then defiant. I think this story is still unfolding.

Do you anticipate upsetting people with the new book? Though the mobs don’t read anything sophisticated, do they?

It’s never about the book or what they read or don’t read, it is about some arbitrary rules they have made about what can be said, what can’t be said, who can say what, who can kill whom – all of that. Yeah, I mean I live here, and I write here, and this book is about here. But the situation here is out of control, from the bottom! It is not about just getting killed, but it is about: How do you even sit in a train or a bus now if you are a Muslim without risking your life? So what happens with me, I have no idea. I’ve written a book and it’s taken me ten years to write it, and there are thirty countries in the world where the biggest publishers are publishing it. I’m not going to allow some idiots to come and disrupt it and snatch all the headlines. Why should I? It is not about their little brains, it is about literature. It has to be protected and tactically done in this climate.

Let’s talk about the book. What was it that made you publish a new novel after spending twenty years being a public intellectual?

Well, this novel has been ten years in the writing, but I think in the twenty years between The God of Small Things and now, I have travelled and been involved with so many things that are happening and written about them at length. There was this huge sense of urgency when I was writing the political essays, each time you wanted to blow a space open, on any issue. But fiction takes its time and is layered. The insanity of what is going on in a place like Kashmir: how do you describe the terror in the air there? It is not just a human rights report about how many people have been killed and where. How do you describe the psychosis of what is going on? Except through fiction.

So that is why you chose…

But it is not that. I didn’t choose to write fiction because I wanted to say something about Kashmir, but fiction chooses you. I don’t think it is that simple that I had some information to impart and therefore I wanted to write a book. Not at all. It is a way of seeing. A way of thinking, it is a prayer, it is a song.

In the book you use a remarkably poetic language to talk about the harshest subjects.

Language is something so natural to you, you know, not something you can manufacture, not for me.

Having studied architecture, you must have at some point thought of that as your field, while today you are one of the most celebrated novelists on the planet. What does your interest in language stem from?

Actually, the idea of language was far before architecture, because in a way architecture came to me as a very pragmatic thing. I left home when I was seventeen and I needed somehow to…

(At this point one of her dogs climbs all over me. I’m more accustomed to dogs barking the moment they see me but, puzzlingly, this one appears to want to lick my face. Arundhati laughs.)

She’s flirting with you. They are both street dogs. She was born outside a drain. Then her mother was hit by a car. That other one I found tied to a lamppost, cruelly.

Do your dogs have names?

Yeah, her name is Begum Filthy Jaan and this one is Maati K. Lal. That means “beloved of the earth”. Both Lal and Jaan mean beloved.

So they make up your family?

Yes.

They’re very well behaved to be street dogs.

Street dogs are more civilized than other dogs. They’re the best. I’m also a bit of a street dog.

I see. So we were talking about your relationship with language and how you left home at 17.

The relationship with language was there from the time I was very, very young. The only thing is that it didn’t seem possible that I would ever be in a position to be a writer.

Why not?

No money… How are you going to earn a living? In the early years of my life my only ambition was to survive somehow, pay my rent. So it didn’t seem like there’d ever be that time where you could actually sit and write something but you’d be so busy earning. It was just a question of: How do you survive?

How did you survive then?

I used to work in this place called the National Institute of Urban Affairs where I earned almost nothing. I used to live in this little hole-in-the-wall near the Nizamuddin Dargah and hire a bicycle for one rupee a day to go to work. All my time I spent thinking about money. (She giggles.)

So at that point you were almost about to become a bureaucrat?

No, no, architect! I could never have become a bureaucrat.

But a government servant?

No, not even that. I was just a temporary, you know at the edges of it.

So then the writing really started with the film scripts?

Basically after Annie [In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones (1989)] – a film that just made its own secret little pathways into the world away from the big hit films – I wrote a second film called Electric Moon and then The God of Small Things. And after that, the essays.

And now you’re making a fiction comeback. Was there any particular idea or incident that triggered off the new book? It seems to be a meditation on the state of the nation.

(She takes a large sip of coffee and rubs her eyes.) ‘It’s a meditation, let’s say, just a meditation. Always, some things spark something and I think in my case I don’t think what sparks it is necessarily what it’s about. Obviously so many years of one’s life and thinking and encounters and all that… but I think one of those nights that I used to spend in front of Jantar Mantar with all these [protesters] who come there, a baby did appear and people were asking: “What to do?” Nobody was sure what to do. So that was one of the things.

I recall that sequence in the novel, and you also narrate many of the individual stories behind the characters you meet at Jantar Mantar?

That was one of the ideas for me that I would – experiment. As you can imagine with any writer who writes a “successful” book, then everybody wants to sign contracts and give you lots of money… and I didn’t want that. I wanted to experiment. I wanted to write a book in which I don’t walk past anyone, even the smallest child, or woman, but sit down, smoke a cigarette, have a chat. It is not a story with a beginning, middle and an end, as much as a map of a city or a building. Or like the structure of a classical raga, where you have these notes and you keep exploring them from different angles, in different ways, different ups, different downs.

About the first hundred pages of the book are set in Old Delhi. What is your relationship to that part of town?

I actually have a place there.

Near Jama Masjid?

Yes, a rented place, a small room, so I’ve been there for many years.

But why do you need that place when you have this apartment?

You sometimes feel under siege. It was not that I went there because I was going to write about it, but because I went there it became very much part [of the book]. I go there, wander around late at night.

All those rabid street dogs, they don’t chase you?

No. Not at all. Humans are rabid, dogs are okay.

The title is intriguing – The Ministry of Utmost Happiness – because inside the book there’s quite a lot of darkness.

But yeah, there’s also quite a lot of light. And the light is in the most unexpected places.

There’s also a character called Tilo, who seems to me very much like Radha in In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones. Is she a continuation of that character?

(She laughs.) She’s not actually like Radha when you carry on [reading]. Yeah, she’s in architecture school, but I think Tilo is a very different person actually.

But how much autobiographical detail do you use in your writing?

It is hard to say, because where does your imagination end and your experience begin? Your memories? It is all a soup. Like in The God of Small Things when Esthappen says, “If in a dream you’ve eaten fish, does it mean you’ve eaten fish?” Or if you’re happy in a dream, does it count? To me this book is not a thinly veiled political essay masquerading as a novel, it is a novel. And in novels, everything gets processed and sweated out on your skin, has to become part of your DNA and it is as complicated as anything that lives inside your body.

On that note, let me ask: in the years you worked on the novel, did you get tired of it at some point or were you happily engrossed in it for an entire decade?

When I write fiction I have a very easy relationship with it in the sense that I’m not in a hurry. Partly, I really want to see if it will live with me, you know, for long. If I got fed up with it, I would leave it and imagine the world would get fed up too. I need to develop a relationship with it almost like…(She goes quiet.)

Like with another human perhaps?

Or a group of humans. We all live together.

Nerdy question time – are there any rituals you have to go through like putting on a jazz record or uncorking a bottle of Old Monk before you start writing?

Let’s say when I was breaking the stones and really trying to understand what I was trying to do I would never be able to work for very long, just a few hours a day. There were two phases in writing this book, one was about generating the smoke, and then it’s like sculpting it, none of which is the same as writing and rewriting, or making drafts. But when you’re generating the smoke, it would be like – I could write three sentences and then just fall asleep out of exhaustion. But when the book was finally clear to me, I’d be working long hours. It was the same with The God of Small Things, there would be that single sentence which would send me to sleep. Like a strange trance almost.

Has your training as an architect been helpful to you?

Not just helped, it is central to the way I write.

How?

Because to me a story is like the map of a city or a map of a building, structured: the way you tell it, the way you enter it, exit it… None of it is simple, straightforward, time and chronology is like building material, so yeah, architecture to me is absolutely central.

I recall Vikram Chandra once telling me how he adapted a construction project management software, used by architects and builders to control the supply chains and all that, to plan and track all the elements in his novel Sacred Games. Do you – as an architect – plan your writing like that?

Oh God! There’s no algorithm involved in my writing, it is all instinctive… rhythm.

What’s a good writing day like then? You get up at five o’clock and take strong coffee or do you wake at three in the afternoon and pour yourself a glass of champagne before hitting the desk?

I don’t seem to have any rituals as such, it is just a very open encounter between me and myself and my writing. I don’t actually understand what we mean by “when you write” because I kind of wonder when am I not writing? I am always writing inside my head! But right now, I feel almost like if I weighed myself, I’d be half my weight, because the last ten years it’s just been in my head, all the time! At least now’ (she points at the book on the kitchen table) ‘it is with me, but it is not on the weighing scale. You know?

What do you do for inspiration?

You know, one of the reasons it would be so hard for me to leave this country, is that everywhere I turn there is something so deep going on. That way I’m lucky in terms of the worlds that I move through here whether it is in the Narmada Valley or in Kashmir. It is a very anarchic, unformatted world that I live in. To me, if anything it is an overload of every kind of stimulus. I suppose I’m not closed off in some family thing. There’s a porous border between me and the world and lots of things come and go. That’s the way I live. There are so many brilliant people doing things around me all the time, like even just in the process of making this book – if I want someone who is an insane … who’s actually not a human being, but a printing machine, I lean this way. If I want someone who is skulking around the city taking pictures, I lean that way. One is just surrounded by unorthodox brilliance all the time. And that’s my real inspiration. If I want really badly behaved dogs I have them too.(She laughs and hugs one of her dogs who is barking in the background, presumably impatient with our interviewing.)

Between writing fiction and non-fiction – which one gives you more pleasure or are they equally satisfactory?

No, there’s no comparison between them for me. Non-fiction is not about pleasure; non-fiction has a sort of urgency to it and another kind of intensity. But fiction is about pleasure. I know for some people it is very painful, but for me not.

What do you do then when you celebrate a good writing day or a well done story? Do you open a bottle of Old Monk?

(She bursts out laughing.)

You’re just stuck on your Old Monk! No, I… I think I just float around.

Arundhati Roy opens her door and lets me in – into her kitchen. I wonder if I’ve knocked on the wrong door: the delivery entrance, perhaps? I quickly hand over the humble gift of fresh coffee beans I’ve brought her, on the assumption that all serious writers love coffee.

As we sit down around her solid wood kitchen table surrounded by funky chairs, I realize that the kitchen is the warm heart of her self-designed apartment in central New Delhi. Apart from long work counters, there’s a sofa, a bookshelf, a sit-out terrace with an antique-looking bench – altogether a place where one could spend a lifetime.

But right now she’s all over the world and is somewhat jet-lagged after having just flown in from New York. Following a bunch of interviews in town, she’s soon off again on a worldwide promotion tour for her new novel. The Ministry of Utmost Happiness is her first in two decades since the globally bestselling, Booker Prize-winning, The God of Small Things. It appears to be the literary happening of the decade and according to her publishers ‘it reinvents what a novel can do and can be’. I’ve started reading it and can say that it is a ruthlessly probing and wide-ranging narrative on contemporary India, written with a linguistic felicity that reminds me of Salman Rushdie’s classic Midnight’s Children. On the whole, it makes interviewing her an intimidating prospect. While she makes coffee, I rig up my electronic defences consisting of three audio recorders (two of which conk out during the interview) and a backup video camera. She looks on bemusedly and seems used to a barrage of microphones. We embark on a three-hour interview session. Excerpts:

Generations of new Indian writers have seen you as an inspiration, as someone who allowed them to dream that one could sit in India and write and then be read all over the world. How does your iconic status feel to you? Do you ever think about it?

Not really, because I am equally balanced by the kind of rage and craziness that I evoke. For me, I live inside my work. Although I must say that I was thinking at some time about writers who like to remain anonymous – but I’ve never been that person. Because, in this country it is important, especially as a woman, to say: “Hey! Here I am! I am going to take you on! And this is what I think and I’m not going to hide.” So if I have helped to give courage to anybody… to experiment… to step out of line… That’s lovely, I think it is very important for us to say: “We can! And we will! And don’t f*** with us!” You know, come on.

I’ve noticed that you don’t often appear at literary festivals. There are more than a hundred in India these days, and I’ve been to quite a few myself, but never met you before. Do you keep away from other writers?

It’s not about other writers. I don’t know if you’ve read this essay I wrote called Capitalism – A Ghost Story and Walking with the Comrades? The thing is that the Jaipur Literature Festival is funded by a kind of notorious mining company that is silencing the voices of the Adivasis, kicking them out of their homes, and now it is also funded by Zee TV which is half the time baying for my blood. So in principle I won’t go. How can I? I’m writing against them. I mean, it’s not that I’m a pure person, like all of us I have contradictions and issues, I’m not like Gandhiji, you know, but in theory I abide by this. How can you be silencing and snuffing out the voices of the poorest people in the world, and then become this glittering platform for free speech and flying writers all around the place? I have a problem with that.

Do you read a lot of new Indian fiction or non-fiction?

When I’ve been writing this book, I haven’t been very up on current things. I’m not even on Facebook and all that. I don’t have any problem [with it], but as Edward Snowden told me, the CIA celebrated when Facebook was started, because they just got all the information without having to collect it. That aside, I think that when you’re writing, you tend to be a bit strange about reading: sometimes I’m not reading whole books, I’m dipping into things to check my own sanity. ’ (She waves her left hand in a kind of elegantly psychedelic mudra before her face.) ‘Am I on the same planet?

Is there any particular Indian writer who you admire?

I think that Naipaul is a very accomplished writer, although we are worlds apart in our worldviews. But I’m not really that influenced by anybody, you know. I have to say that I find it incredible that writers in India, or almost all Indian writers, or at least the well-known writers… Let’s not say writers, but there’s been a level of eliding of things that have been at the heart of the society, like caste. You see there is something very wrong here. It is like people in apartheid South Africa writing without mentioning that there is apartheid.

Your writing is hard-hitting and outspoken – have you experienced any adverse repercussions?

My God, that’s to put it mildly. Other than of course going to jail and all that. Even now, when the last book of essays was released in Delhi, called Broken Republic, a gang of vigilantes came on stage, smashed the stage up. The right wing, the mobs, vigilantes, they are there at every meeting, threatening violence, threatening all kinds of things. I still go to speak, to Punjab, in Orissa, wherever, I’m not really that writer who is sequestered somewhere and I live perhaps alone, but in the heart of the crowd.

It must have been a bit of a shock, after expressing a personal opinion, to suddenly find yourself behind bars in Tihar Jail?

Tihar. (She sighs deeply.) Yes, it is shocking, but at the same time look at how many thousands of people are behind bars, people who have no understanding of the language, who don’t even know what they’re charged with. So I can’t really be dramatic about what happened to me, because people are in jail for years for nothing – nothing! It’s crazy! I’m currently being tried for contempt of court again for an essay I wrote called Professor P.O.W. which you can read in Outlook Magazine.

Have you ever felt that you should leave India and live in a country where you don’t have to face such problems?

Everything that I know is here! Everyone that I know! And I’ve never really lived outside, abroad, so the idea of going to live all alone in some strange country is also terrifying. But right now I think India is poised in an extremely dangerous place, I don’t know what is going to happen to anybody – to me or to anybody. There are just these mobs that decide who should be killed, who should be shot, who should be lynched, you know? I think it is probably the first time that people in India, writers and other people, are facing the kind of trauma that people have faced in Chile and Latin America. There’s a kind of terror building up here which we have not fully got the measure of. You go through periods when you are feeling very worried, then angry, and then defiant. I think this story is still unfolding.

Do you anticipate upsetting people with the new book? Though the mobs don’t read anything sophisticated, do they?

It’s never about the book or what they read or don’t read, it is about some arbitrary rules they have made about what can be said, what can’t be said, who can say what, who can kill whom – all of that. Yeah, I mean I live here, and I write here, and this book is about here. But the situation here is out of control, from the bottom! It is not about just getting killed, but it is about: How do you even sit in a train or a bus now if you are a Muslim without risking your life? So what happens with me, I have no idea. I’ve written a book and it’s taken me ten years to write it, and there are thirty countries in the world where the biggest publishers are publishing it. I’m not going to allow some idiots to come and disrupt it and snatch all the headlines. Why should I? It is not about their little brains, it is about literature. It has to be protected and tactically done in this climate.

Let’s talk about the book. What was it that made you publish a new novel after spending twenty years being a public intellectual?

Well, this novel has been ten years in the writing, but I think in the twenty years between The God of Small Things and now, I have travelled and been involved with so many things that are happening and written about them at length. There was this huge sense of urgency when I was writing the political essays, each time you wanted to blow a space open, on any issue. But fiction takes its time and is layered. The insanity of what is going on in a place like Kashmir: how do you describe the terror in the air there? It is not just a human rights report about how many people have been killed and where. How do you describe the psychosis of what is going on? Except through fiction.

So that is why you chose…

But it is not that. I didn’t choose to write fiction because I wanted to say something about Kashmir, but fiction chooses you. I don’t think it is that simple that I had some information to impart and therefore I wanted to write a book. Not at all. It is a way of seeing. A way of thinking, it is a prayer, it is a song.

In the book you use a remarkably poetic language to talk about the harshest subjects.

Language is something so natural to you, you know, not something you can manufacture, not for me.

Having studied architecture, you must have at some point thought of that as your field, while today you are one of the most celebrated novelists on the planet. What does your interest in language stem from?

Actually, the idea of language was far before architecture, because in a way architecture came to me as a very pragmatic thing. I left home when I was seventeen and I needed somehow to…

(At this point one of her dogs climbs all over me. I’m more accustomed to dogs barking the moment they see me but, puzzlingly, this one appears to want to lick my face. Arundhati laughs.)

She’s flirting with you. They are both street dogs. She was born outside a drain. Then her mother was hit by a car. That other one I found tied to a lamppost, cruelly.

Do your dogs have names?

Yeah, her name is Begum Filthy Jaan and this one is Maati K. Lal. That means “beloved of the earth”. Both Lal and Jaan mean beloved.

So they make up your family?

Yes.

They’re very well behaved to be street dogs.

Street dogs are more civilized than other dogs. They’re the best. I’m also a bit of a street dog.

I see. So we were talking about your relationship with language and how you left home at 17.

The relationship with language was there from the time I was very, very young. The only thing is that it didn’t seem possible that I would ever be in a position to be a writer.

Why not?

No money… How are you going to earn a living? In the early years of my life my only ambition was to survive somehow, pay my rent. So it didn’t seem like there’d ever be that time where you could actually sit and write something but you’d be so busy earning. It was just a question of: How do you survive?

How did you survive then?

I used to work in this place called the National Institute of Urban Affairs where I earned almost nothing. I used to live in this little hole-in-the-wall near the Nizamuddin Dargah and hire a bicycle for one rupee a day to go to work. All my time I spent thinking about money. (She giggles.)

So at that point you were almost about to become a bureaucrat?

No, no, architect! I could never have become a bureaucrat.

But a government servant?

No, not even that. I was just a temporary, you know at the edges of it.

So then the writing really started with the film scripts?

Basically after Annie [In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones (1989)] – a film that just made its own secret little pathways into the world away from the big hit films – I wrote a second film called Electric Moon and then The God of Small Things. And after that, the essays.

And now you’re making a fiction comeback. Was there any particular idea or incident that triggered off the new book? It seems to be a meditation on the state of the nation.

(She takes a large sip of coffee and rubs her eyes.) ‘It’s a meditation, let’s say, just a meditation. Always, some things spark something and I think in my case I don’t think what sparks it is necessarily what it’s about. Obviously so many years of one’s life and thinking and encounters and all that… but I think one of those nights that I used to spend in front of Jantar Mantar with all these [protesters] who come there, a baby did appear and people were asking: “What to do?” Nobody was sure what to do. So that was one of the things.

I recall that sequence in the novel, and you also narrate many of the individual stories behind the characters you meet at Jantar Mantar?

That was one of the ideas for me that I would – experiment. As you can imagine with any writer who writes a “successful” book, then everybody wants to sign contracts and give you lots of money… and I didn’t want that. I wanted to experiment. I wanted to write a book in which I don’t walk past anyone, even the smallest child, or woman, but sit down, smoke a cigarette, have a chat. It is not a story with a beginning, middle and an end, as much as a map of a city or a building. Or like the structure of a classical raga, where you have these notes and you keep exploring them from different angles, in different ways, different ups, different downs.

About the first hundred pages of the book are set in Old Delhi. What is your relationship to that part of town?

I actually have a place there.

Near Jama Masjid?

Yes, a rented place, a small room, so I’ve been there for many years.

But why do you need that place when you have this apartment?

You sometimes feel under siege. It was not that I went there because I was going to write about it, but because I went there it became very much part [of the book]. I go there, wander around late at night.

All those rabid street dogs, they don’t chase you?

No. Not at all. Humans are rabid, dogs are okay.

The title is intriguing – The Ministry of Utmost Happiness – because inside the book there’s quite a lot of darkness.

But yeah, there’s also quite a lot of light. And the light is in the most unexpected places.

There’s also a character called Tilo, who seems to me very much like Radha in In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones. Is she a continuation of that character?

(She laughs.) She’s not actually like Radha when you carry on [reading]. Yeah, she’s in architecture school, but I think Tilo is a very different person actually.

But how much autobiographical detail do you use in your writing?

It is hard to say, because where does your imagination end and your experience begin? Your memories? It is all a soup. Like in The God of Small Things when Esthappen says, “If in a dream you’ve eaten fish, does it mean you’ve eaten fish?” Or if you’re happy in a dream, does it count? To me this book is not a thinly veiled political essay masquerading as a novel, it is a novel. And in novels, everything gets processed and sweated out on your skin, has to become part of your DNA and it is as complicated as anything that lives inside your body.

On that note, let me ask: in the years you worked on the novel, did you get tired of it at some point or were you happily engrossed in it for an entire decade?

When I write fiction I have a very easy relationship with it in the sense that I’m not in a hurry. Partly, I really want to see if it will live with me, you know, for long. If I got fed up with it, I would leave it and imagine the world would get fed up too. I need to develop a relationship with it almost like…(She goes quiet.)

Like with another human perhaps?

Or a group of humans. We all live together.

Nerdy question time – are there any rituals you have to go through like putting on a jazz record or uncorking a bottle of Old Monk before you start writing?

Let’s say when I was breaking the stones and really trying to understand what I was trying to do I would never be able to work for very long, just a few hours a day. There were two phases in writing this book, one was about generating the smoke, and then it’s like sculpting it, none of which is the same as writing and rewriting, or making drafts. But when you’re generating the smoke, it would be like – I could write three sentences and then just fall asleep out of exhaustion. But when the book was finally clear to me, I’d be working long hours. It was the same with The God of Small Things, there would be that single sentence which would send me to sleep. Like a strange trance almost.

Has your training as an architect been helpful to you?

Not just helped, it is central to the way I write.

How?

Because to me a story is like the map of a city or a map of a building, structured: the way you tell it, the way you enter it, exit it… None of it is simple, straightforward, time and chronology is like building material, so yeah, architecture to me is absolutely central.

I recall Vikram Chandra once telling me how he adapted a construction project management software, used by architects and builders to control the supply chains and all that, to plan and track all the elements in his novel Sacred Games. Do you – as an architect – plan your writing like that?

Oh God! There’s no algorithm involved in my writing, it is all instinctive… rhythm.

What’s a good writing day like then? You get up at five o’clock and take strong coffee or do you wake at three in the afternoon and pour yourself a glass of champagne before hitting the desk?

I don’t seem to have any rituals as such, it is just a very open encounter between me and myself and my writing. I don’t actually understand what we mean by “when you write” because I kind of wonder when am I not writing? I am always writing inside my head! But right now, I feel almost like if I weighed myself, I’d be half my weight, because the last ten years it’s just been in my head, all the time! At least now’ (she points at the book on the kitchen table) ‘it is with me, but it is not on the weighing scale. You know?

What do you do for inspiration?

You know, one of the reasons it would be so hard for me to leave this country, is that everywhere I turn there is something so deep going on. That way I’m lucky in terms of the worlds that I move through here whether it is in the Narmada Valley or in Kashmir. It is a very anarchic, unformatted world that I live in. To me, if anything it is an overload of every kind of stimulus. I suppose I’m not closed off in some family thing. There’s a porous border between me and the world and lots of things come and go. That’s the way I live. There are so many brilliant people doing things around me all the time, like even just in the process of making this book – if I want someone who is an insane … who’s actually not a human being, but a printing machine, I lean this way. If I want someone who is skulking around the city taking pictures, I lean that way. One is just surrounded by unorthodox brilliance all the time. And that’s my real inspiration. If I want really badly behaved dogs I have them too.(She laughs and hugs one of her dogs who is barking in the background, presumably impatient with our interviewing.)

Between writing fiction and non-fiction – which one gives you more pleasure or are they equally satisfactory?