“Blessed is the nation that doesn’t need heroes" Goethe. “Hero-worship is strongest where there is least regard for human freedom.” Herbert Spencer. "My 80% friend isn't my 20% enemy" Ronald Reagan.

Search This Blog

Sunday 1 January 2023

Wednesday 12 October 2022

Monday 20 June 2022

BREXIT - The Great Taboo in British Politics

George Parker and Chris Giles in The FT

As he battled to save his job this month, Boris Johnson warned his MPs not get into “some hellish, Groundhog Day debate about the merits of belonging to the single market”. Brexit, he warned his mutinous party in a sweaty House of Commons meeting room, was settled.

Later that day, Johnson limped to victory in a confidence vote, but only after 41 per cent of his MPs had voted to oust him from Downing Street. He is safe for now but the defining project of his premiership — Brexit — still hangs like a cloud over Britain’s fragile economy.

Johnson may not want his party “relitigating” Brexit but neither does Sir Keir Starmer, leader of the opposition Labour party, around a third of whose supporters voted Leave in the 2016 referendum. Nor does Andrew Bailey, governor of the Bank of England. Rishi Sunak, the chancellor, would rather talk about something else. Brexit has become the great British taboo.

But as the sixth anniversary of the UK’s vote to leave the EU approaches, economists are starting to quantify the damage caused by the erection of trade barriers with its biggest market, separating the “Brexit effect” from the damage caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. They conclude that the damage is real and it is not over yet.

The UK is lagging behind the rest of the G7 in terms of trade recovery after the pandemic; business investment, seen by Johnson and Sunak as the panacea to a poor growth rate, trails other industrialised countries, in spite of lavish Treasury tax breaks to try to drive it up. Next year, according to the OECD think-tank, the UK will have the lowest growth in the G20, apart from sanctioned Russia.

The Office for Budget Responsibility, the official British forecaster, has seen no reason to change its prediction, first made in March 2020, that Brexit would ultimately reduce productivity and UK gross domestic product by 4 per cent compared with a world where the country remained inside the EU. It says that a little over half of that damage has yet to occur.

That level of decline, worth about £100bn a year in lost output, would result in lost revenues for the Treasury of roughly £40bn a year. That is £40bn that might have been available to the beleaguered Johnson for the radical tax cuts demanded by the Tory right — the equivalent of 6p off the 20p in the pound basic rate of income tax.

Despite these sobering figures, Johnson’s complaints about the prospect of “relitigating” Brexit was exaggerated, intended to portray himself as the victim of a putative plot by pro-Remain MPs. In fact, British politicians — and the wider country — are still traumatised by the bitter Brexit saga, and deeply unwilling to revisit it.

Still, this month has seen the first stirrings of a debate that until now has been buried as the evidence of Brexit-induced economic self-harm starts to pile up. Few are talking about reversing Brexit altogether, but another question is being asked: should the UK start to explore with Brussels ways of softening its edges?

Show, don’t tell

Downing Street insisted this week it was “too early to pass judgment” on whether Brexit was having a negative impact on the economy, which could be heading into a recession. “The opportunities Brexit provides will be a boon to the UK economy in the long run,” Johnson’s spokesman said.

Both Johnson and Sunak insist that it is hard at this stage to separate Brexit’s economic impact from the shock of Covid. In the meantime, the prime minister promotes the “benefits of Brexit”, such as new trade agreements with Australia and New Zealand and the freedom for the UK to set its own rules.

Sunak has promised a reform of rules in the City of London, including reforming the EU’s Solvency II rules to allow insurers to spend more money on infrastructure projects. He has announced eight new freeports with special tax privileges.

But economists have not yet been able to find any significant positive impacts of these policies. Some, including Johnson’s patriotic promise to put a “crown stamp” on pint glasses in pubs and to allow traders to sell their wares in pounds and ounces, are primarily symbolic.

Critics of government Brexit policy are routinely derided. Suella Braverman, attorney-general, last week accused the ITV presenter Robert Peston of “Remainiac make-believe” after he challenged her over the government’s unilateral plan to rip up the Brexit treaty relating to Northern Ireland. Braverman claimed the so-called Northern Ireland protocol had left the region “lagging behind the rest of the UK”. In fact, Northern Ireland (the only area of the UK to remain in the EU’s single market for goods) is the best performing part of the country, apart from London.

When Bailey appeared before the House of Commons treasury committee in mid May, the BoE governor acknowledged that his predecessor Mark Carney had made himself “unpopular” for saying Brexit would have a negative effect on trade, but that the bank held to that view.

Kevin Hollinrake, a Tory member of the committee, says Bailey was trying to avoid becoming a political target and was “deliberately avoiding” talking about Brexit. “It’s a singular issue for the UK,” the MP says. “We have changed our immigration rules. It’s about non-tariff barriers. You’ve got to be willing to look at what’s happening on the ground.”

While some gloomy predictions have failed to materialise, such as former chancellor George Osborne’s 2016 warning of a recession immediately after a Leave vote, there is growing evidence that Brexit is causing more lasting damage to UK economic prospects.

Ministers are becoming more reluctant to proclaim the economic upsides of Brexit. Kwasi Kwarteng, business secretary, was asked last week at the FT Global Boardroom to list some Brexit benefits. He focused on the UK’s ability to respond swiftly to Russian aggression in Ukraine — “it has substantial benefits particularly in international policy” — rather than on business. Sunak’s allies say the chancellor’s approach is to “show, not tell” on Brexit, pushing through City regulatory reforms rather than giving boosterish speeches on its economic merits.

The fallout in data

The first and most obvious economic blow delivered by Brexit came when sterling fell almost 10 per cent after the referendum in June 2016, against currencies that match the UK’s pattern of imports. It did not recover. This sharp depreciation was not followed by a boom in exports as UK goods and services became cheaper on global markets, but it did raise the price of imports and pushed up inflation.

By June 2018, a team of academic economists at the Centre for Economic Policy Research calculated that there had been a Brexit inflation effect, raising consumer prices by 2.9 per cent, with no corresponding increase in wages.

Some households, such as those relying on state pensions, were compensated in higher benefits, but the CEPR team found no overall offset with higher incomes. “The Brexit vote delivered a swift negative shock to UK living standards,” they wrote.

While the UK was still in the EU and during the Brexit “transition phase”, there were no significant effects on trade flows. But this has changed since stricter border controls were introduced at the start of 2021, imposing no tariffs, but significant checks and controls at the formerly frictionless border.

Economists have used this point in time to contrast how the UK’s trade performance compares with those of other countries before and after the TCA’s imposition. The results have been increasingly ugly, especially for small companies trading with Europe.

Red tape caused a “steep decline” in the number of trading relationships after January 2021, according to a study by the Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics. The number of buyer-seller relationships fell by almost one-third, it found.

The same group found food prices had risen as a result of Brexit. Comparing the prices of imported food such as pork, tomatoes and jam, which predominantly came from the EU, with those that came from further afield such as tuna and pineapples, it found a substantial Brexit effect. “Brexit increased average food prices by about 6 per cent over 2020 and 2021,” according to the research.

Summing up the effects on trade in which imports from the EU have fallen while exports have not risen, Adam Posen, head of the Peterson Institute of International Economics, says “everybody else sees a recovery in trade following Covid and the UK sits flat”.

The third visible effect of Brexit on the UK economy has been in discouraging business investment. In the first quarter of 2022, real business investment was 9.4 per cent lower than in the second quarter of 2016. That fall was mostly due to Covid, but it had flatlined since the referendum, ending a period of growth since 2010 and falling well short of the performance of other G7 countries.

Weak investment is a particular worry for Sunak, who sees business investment as the route to greater prosperity. Before departing the BoE in 2020, Carney told a House of Lords Committee that Brexit uncertainty was holding back business investment. Worse, he said, business planning for various Brexit scenarios was taking up a lot of management effort. “Time spent on contingency planning is time not spent on strategic initiatives,” he said.

Since then, negative perceptions of the UK have continued among business with the chancellor finding he had little bang for his £25bn buck of super deductions in corporation tax to encourage capital spending. As Bailey told MPs last month, the super-deductor was “not at the moment having the impact that was expected”.

Complaints about high immigration was one of the most contentious issues of the referendum, with a central promise of the Brexit campaign being tougher controls over the number of people entering the country. While net immigration from EU countries has stopped, with effectively no change apparent in the two years to the end of June 2021, net immigration from non EU countries has remained high, with 250,000 in the latest year.

Collateral damage

There is, as yet, little appetite among Britain’s political leaders for a return to the EU — even if the other 27 member states were prepared to open the door. Even the pro-EU Liberal Democrats admit reversing course is a long-term aspiration, rather than an immediate goal.

As part of his attempt to avert a coup, Johnson wrote to MPs this month that he had “created a new and friendly relationship with the EU”. The opposite is true. Brussels restarted legal action against the UK this week over the Northern Ireland protocol: relations are at rock bottom.

The EU has warned that British scientists will be excluded from the €95bn Horizon research programme as “collateral damage” in the row about Northern Ireland. The prospect of any kind of rapprochement at the moment, at least while Johnson remains prime minister, seems remote.

But in recent weeks, a tentative debate has started over whether the UK would be better off trying to reach accommodations with the EU to smooth trade in some areas, rather than launching a new front in the Brexit war with unilateral action over Northern Ireland.

In an article much-discussed at Westminster, the pro-Leave Times columnist Iain Martin wrote this month: “To deny the downsides of Brexit on trade with the EU is to deny reality.”

Tobias Ellwood, a former Tory defence minister, suggested Britain should rejoin the EU single market to soften the cost of living crisis, and said there was “an appetite” for a rethink and claimed polling indicated “this is not the Brexit most people imagined”. And Daniel Hannan, a leading Tory Brexiter, repeated his longstanding view that Britain should have stayed in the single market under a Norway-style relationship with the EU, while adding that to rejoin it now “would be madness”.

Anna McMorrin, Labour shadow minister, was recorded telling activists: “I hope eventually that we will get back into the single market and customs union.” She was forced to apologise by Starmer: such talk remains dangerous in political circles.

Even so, a Starmer-led future Labour government would change UK relations with the EU. The party’s mantra has become “make Brexit work”: rejoining the single market may be off the agenda, but Labour wants to find ways to improve on the bare-bones tariff-free trade agreement Johnson negotiated with the EU.

Rachel Reeves, the shadow chancellor, told the Financial Times last year that Labour wanted to strike a deal with the EU to reduce the most onerous paperwork and checks on food exports. The party also wants an agreement with Brussels on the mutual recognition of professional qualifications.

Even among the Eurosceptics in Johnson’s cabinet, there is now an acceptance that the UK should be seeking to rebuild economic relations with the EU, including in areas like the Horizon programme, to avoid exacerbating the looming cost of living crisis.

“Would I like to be in a better place on Brexit?” asked one pro-Brexit cabinet member. “Yes, absolutely. But we’ve got to find a way of doing it without it looking like we’re running up the white flag and we’re compromising on sovereignty.”

Friday 22 April 2022

The Perils Of Conceptual Reality

I’m sure by now you must have come across people (mostly on social media) who let loose a barrage of words as a reaction to what they believe is an anti-Imran-Khan tweet or post. The words are almost always,”looters,” “corrupt,” “chor,” and “traitors.” These words are dedicated to parties and leaders who till recently were in the opposition and are now in government (after ousting Khan).

Very rarely can one find a pro-Khan or pro-PTI person actually listing the successes of the ousted PM’s economic or social policies. But the fact is: as much as such folk are rare, so are the previous government’s successes. If one still believes that this is not the case, he or she needs to provide some intelligent, informed arguments so that an exchange can turn into a debate — instead of a hyper-monologue in which a single person is frantically crackling like a broken record: “looters, corrupt, chor, traitors!”

Is this person stupid? Not quite. Because one even saw some apparently intelligent men and women crackling in the same manner when Khan fell. To most critics of populism, people who voted for men such as India’s Narendra Modi, America’s Donald Trump, Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro, Hungary’s Viktor Orban, Poland’s Andrzej Duda and Pakistan’s Imran Khan, were all largely ‘stupid.’

But what is stupidity? Ever since the mid-20th century, the idea of stupidity, especially in the context of politics, has been studied by various sociologists. One of the pioneers in this regard was the German scholar and theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer. During the rise of Nazi rule in Germany, Bonhoeffer was baffled by the silence of millions of Germans when the Nazis began to publicly humiliate and brutalise Jewish people. Bonhoeffer condemned this. He asked: how could a nation that had produced so many philosophers, scientists and artists suddenly become so apathetic and even sympathetic towards state violence and oppression?

Unsurprisingly, in 1943, Bonhoeffer was arrested. Two years later, he was executed. While awaiting execution, Bonhoeffer began to put his thoughts on paper. These were posthumously published in the shape of a book, Letters and Papers from Prison. One of the chapters in the book is called, “On Stupidity.” Bonhoeffer wrote: “Every strong upsurge of power in the public sphere, be it political or religious, infects a large part of humankind with stupidity. The power of the one needs the stupidity of the other.”

According to Bonhoeffer, because of the overwhelming impact of a rising power, humans are deprived of their inner independence and they give up establishing an autonomous position towards the emerging circumstances. It is a condition in which people become mere tools in the hands of those in power, and begin to willingly surrender their capacity for independent thinking. Bonhoeffer wrote that holding a rational debate with such a person is futile, because it feels that one is not dealing with a person, but with slogans and catchwords. “Looters, corrupt, chor, traitors!” ‘Looters, corrupt, chor, traitors!’ Repeat.

But Khan did not rise. He fell. Truth is: this condition in which a person becomes a walking-talking instrument of repetitive slogans and catchwords, first appeared during Khan’s rise to power. During that period “looters, corrupt, chor, traitors” were active words, deployed to justify Khan’s rise, and the demise of his opponents. After his fall, the same words have become reactive. Either way, neither then nor now is this condition suitable for a more informed debate between two (or more) opposing ideas or narratives.

Does this mean that most Khan fans are incapable of having such a debate? Many may not be very well-informed about the ins and outs of politics or history, but does that make them stupid — even though sometimes they certainly sound it?

To Bonhoeffer, stupidity was not about lack of intelligence, but about a mind that had voluntarily closed itself to reason, especially after being impacted and/or swayed by an assertive external power. In a 2020 essay for The New Statesman, the British philosopher Sacha Golob wrote that being stupid and dumb were not the same thing. Intelligence (or lack thereof) can somewhat be measured through IQ tests. But even those who score high in these tests can do ‘stupid’ things or carry certain ‘stupid ideas.’

How could a man who had created a rather convincing empiricist and rationalist character such as Sherlock Holmes begin to believe in seances? In fact, Doyle also began to believe in the existence of fairies. Every time someone would successfully debunk Doyle’s beliefs, he would go to great lengths to provide a counter-argument, but one which was even more absurd.

Golob wrote that stupidity can thus be found in supposedly very intelligent people as well. According to the American psychologist Ray Hyman, “Conan Doyle used his smartness to outsmart himself.” This can also answer why one sometimes comes across highly educated and informed men and women unabashedly spouting conspiracy theories that have either been convincingly debunked, or cannot be proven outside the domain of wishful thinking. But why would one do that?

There can be various reasons for this. According to Golob, Doyle, who had already developed some interest in ‘spirituality,’ began dabbling in the supernatural after the death of his son. According to Golob, “Doyle used his intellect to weave a path through grief that, although obviously irrational, was personally restorative.” So, it can be a way to live through grief or a personal tragedy which things like reason, rationality or logic cannot address. But this does not mean that the thousands of intelligent people who begin to mouth irrational populist hogwash all suffer personal tragedies. Yet, in the context of politics, resentfulness and grief can be triggered in a class or tribe if it is convinced that it has been neglected, mocked or sidelined by a ‘political elite.’

In the US, folk in the ‘rural’ South felt exactly that. They felt their ideas and lifestyles were mocked by the ‘liberal elite’ for being backward, anti-modern and superstitious. Their resentment in this regard was brilliantly tapped by Donald Trump. And even though the Southern states in the US have the largest number of Christian fundamentalists and regular Church-goers in that country, they continued to support Trump despite his involvement in scandals both of the flesh and finances.

This brings us back to Nazi Germany and Bonhoeffer. A nation was left grief-stricken by a humiliating defeat (during the First World War). It was thus willing to suspend all critical thinking after the grief was first treated with a barrage of conspiracy theories (blaming the Jews), and then by a man who became a powerful conduit of these theories. His rise was the sum of collective resentment and grief. It was a negation of empirical reality where a society was trapped in a serious existential crisis.

Theoretically, the crisis could have been addressed in a rational manner as well (such as through the continuation of the democratic process). But such processes evolve slowly and come to be seen as part of a reality that is pregnant with crisis. The answers to such a malaise often come in the shape of ‘conceptual reality.’ Empirical realty is the reality which one interacts with on a daily basis through the senses. Conceptual realty, on the other hand, is created and fuelled by certain ideological drivers or by what one thinks empirical reality should actually be. Conceptual reality is an imagined world but is stuffed with claims and physical paraphernalia to make it seem like empirical reality.

The promise of a ‘thousand-year-Reich’ by the Nazis was a fantasy that used physical symbols (such as a messiah-like leader, large rallies and public marches, uniforms, imposing architecture, etc.) to replace an empirical reality with a conceptual one. And when a person escapes into a conceptual reality, communicating with him or her on an empirical and rational level becomes next to impossible.

1983 copy of US government instructions to its embassies in Muslim countries on how to ‘politely’ deny that astronaut Neil Armstrong had converted to Islam

1983 copy of US government instructions to its embassies in Muslim countries on how to ‘politely’ deny that astronaut Neil Armstrong had converted to IslamConceptual reality is a product of – and mostly appeals to – people who have developed a persecution complex because they failed to find an identity or purpose in the empirical reality. So, they dismiss it and look to replace the ‘what is’ with the ‘what (they believe) should be’. This is fine if they can do so while remaining within the empirical reality. But the results can be disastrous when they reject empirical reality by losing themselves in building a conceptual reality. This reality is utopian. But when manifested physically, it quickly becomes dystopian, myopic and even delusional.

German historian Markus Daechsel has brilliantly demonstrated this in his book The Politics of Self Expression. Conceptual reality includes the projection of one’s religious and ideological beliefs on people that have little or nothing to do with them. Conceptual reality also entails projections that are often proliferated through populist media as a way to concretise conceptual reality.

Daechsel gave the example of certain pre-Partition Muslim and Hindu outfits who insisted that their members wear a uniform and hold parades. Daechsel writes that in the empirical reality, there was no war or revolution taking place there. But in the minds of the members of the outfits, there was such a situation (or there should have been). So, they created a conceptual reality in which there was revolutionary turmoil and these outfits were an integral part of it.

Daechsel also gave the example in which Hindus and Muslims, after feeling unable to challenge Western inventions and economics in the empirical reality, created a conceptual reality by claiming that whatever the West had achieved in the fields of science had already been achieved by ancient Hindus and/or is already present in Islamic texts.

In the late 1970s, tabloids in Indonesia, Malaysia and Egypt carried a front-page news about Neil Armstrong — the famous American astronaut who, in 1969, became the first man to walk on the moon. The news claimed that Armstrong had converted to Islam. Supposedly he had done so after confessing that when he was on the moon, he had heard the sound of the azaan, the Muslim call to prayer.

Conceptual reality can be a very emotional place

Conceptual reality can be a very emotional placeJ.R. Hensen, in his 2006 biography of Armstrong, First Man, writes that by 1980 the news had been repeatedly carried and reproduced by tabloids in a number of Muslim-majority countries. So much so, that Armstrong began receiving invitations from Islamic organisations. The news continued to gather momentum in Muslim countries. Hensen writes that in 1983, on Armstrong’s request, the US State Department issued instructions to US embassies in Muslim countries asking them to “politely but firmly” communicate that Armstrong had not converted to Islam and that “he had no current plans or desire to travel overseas to participate in Islamic activities.”

Despite this, the belief that he had converted to Islam after hearing the azaan on the moon continued to do the rounds. In fact, this impression still pops up on YouTube channels and websites funded and run by various Islamic evangelical organisations. This is a case of how a conceptual reality (in this case, the power of ‘Eastern spirituality’) compelled a member of empirical reality (Western science and technology) to leave the latter and embrace the former.

In December 2018, former PM Imran Khan gleefully shared a 1988 video recording on Twitter of conservative Islamic scholar Dr Israr Ahmad. In it, Ahmad is seen claiming that according to one of Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s doctors, the founder of Pakistan, during his last moments, spoke about the importance of imposing Shariah laws and the caliphate system in Pakistan.

This was conceptual reality coming into play to counter the reality in which Jinnah had done no such thing and was, in fact, a Westernised and pluralistic politician. This nature of projection of a conceptual reality actually goes further back.

The day after the founder of the modern Turkish republic Kemal Ataturk passed away in November 1939, one of the leading Urdu dailies in pre-Partition India, the Inqilab, reported that Ataturk, who had slipped into a coma before his death, “briefly woke up to convey a message to a servant of his.” Apparently, the staunch, life-long secularist who went the whole nine yards during his long rule to erase all cultural and political expressions associated with Turkey’s caliphate past, had briefly woken up from a coma to instruct his servant to tell the “millat-i-Islamiyya” to follow on the footsteps of the Khulafa-i-Rashideen.

Inqilab was a well-respected Urdu daily catering to the urban Muslim middle classes in pre-Partition India. In its 11 November 1939 issue, the paper went on to ‘report’ that Ataturk, after communicating his message to the servant, shouted “Allah is great!” and passed away – this time, forever. Quite clearly, unable to come to terms with the dispositions of Ataturk and Jinnah in the empirical reality, some created a conceptual reality where, in death, both dramatically became caliphate enthusiasts.

Let us now take a more contemporary example: the so-called ‘US conspiracy’ that ousted Imran Khan as PM. This is being repeated over and over again by Khan, his supporters and some half-a-dozen TV anchors. In empirical reality, the performance of Khan’s regime compelled its erstwhile pillar of support, the powerful military establishment, to begin distancing itself from a malfunctioning government. This created space for opposition parties to conjure enough strength in the Parliament to remove him through a no-confidence vote.

However, in the conceptual reality — that began being constructed by Khan when his ouster became a stark possibility — US and European powers conspired with opposition parties and pressurised the military to oust Khan because he wanted a sovereign foreign policy and was planning to construct an anti-West bloc in the region. There is no empirical evidence that substantiates the existence of a foreign conspiracy. But then, there is no place for anything empirical in a realm that is entirely conceptual.

Sunday 6 March 2022

Friday 25 February 2022

Boris Johnson claims the UK is rooting out dirty Russian money. That’s ludicrous

Oliver Bullough in The Guardian

We were warned about Vladimir Putin – about his intentions, his nature, his mindset – and, because it was profitable for us, we ignored those warnings and welcomed his friends and their money. It is too late for us to erase our responsibility for helping Putin build his system. But we can still dismantle it and stop it coming back.Russia is a mafia state, and its elite exists to enrich itself. Democracy is an existential threat to that theft, which is why Putin has crushed it at home and seeks to undermine it abroad. For decades, London has been the most important place not only for Russia’s criminal elite to launder its money, but also for it to stash its wealth. We have been the Kremlin’s bankers, and provided its elite with the financial skills it lacks. Its kleptocracy could not exist without our assistance. The best time to do something about this was 30 years ago – but the second best time is right now.

We journalists have long been writing about this, but it is not simply overheated rhetoric from overexcited hacks. Parliament’s intelligence and security committee wrote two years ago that our investigative agencies are underfunded, our economy is awash with dirty money, and oligarchs have bought influence at the very top of our society.

The committee heard evidence from senior law enforcement and security officials. It laid out detailed, careful suggestions for what Britain should do to limit the damage Putin has already done to our society. Instead of learning from the report and implementing its proposals, Boris Johnson delayed its publication until after the general election and then, when further delay became impossible, dismissed those who took its sober analysis seriously as “Islingtonian remainers” seeking to delegitimise Brexit.

That is the crucial context for Johnson’s ludicrous claim this week to the House of Commons that no government could “conceivably be doing more to root out corrupt Russian money”. That is not only demonstrably untrue, it is an inversion of reality. On leaving the European Union, we were told that we could launch our own independent sanctions regime – and this week we saw the fruit of it: a response markedly weaker than those of Brussels and Washington.

The Liberal Democrat MP Layla Moran, speaking with parliamentary privilege on Tuesday, listed the names of 35 alleged key Putin “enablers” whom the Russian opposition politician Alexei Navalny has asked to be sanctioned. Blocking the assets of everyone on that list and their close relatives would be a truly significant response from Johnson to the gravity of the situation. But it would still only be a start.

Relying solely on sanctions now is like stamping on a car’s accelerator when you’ve failed for years to maintain the engine, pump up the tyres or fill up the tank, yet still expect it to hit 95mph. Other announcements in the last couple of days have amounted to nothing more than painting on go-faster stripes. Tackling the UK’s role in enabling Putin’s kleptocracy, and containing the threat his allies pose to democracy here and elsewhere, will require far more than just banning golden visas or Kremlin TV stations.

For a start, we need to know who owns our country. Some 87,000 properties in England and Wales are owned via offshore companies – which prevents us seeing who their true owners are or if they were bought with criminal money. Companies House makes no checks on registrations, which is why UK shell structures have featured in most Russian money-laundering scandals. Imposing transparency on the ownership of dirty money in this way would strike at the heart of the London money-laundering machine. Governments have promised to do this “when parliamentary time allows” for years, yet the time has never been found, and instead they’ve listened to concerns from the City that such regulations would harm its competitiveness.

Above all, we need to fund our enforcement agencies as generously as oligarchs fund their lawyers: you can’t fight grand corruption on the cheap. Even good policies of recent years, such as the “unexplained wealth orders” of 2017, which were designed to tackle criminally owned assets hidden behind clever shell structures, have largely failed because investigators lack the funds to use them. We must spend what it takes to drive kleptocratic cash out of the country.

Johnson is not the first prime minister to fail to rise to the challenge – Tony Blair and David Cameron both schmoozed with Putin even when it was obvious what kind of a leader he was. And I don’t think Johnson is personally corrupt or tainted by Russian money; he’s lazy, flippant and unwilling to launch expensive, laborious initiatives that will bring results only long after he himself has left office and is unable to take the credit for them. It is time, however, for his colleagues to step up and force him into action. This is a serious moment, and it requires serious people willing to invest in the long-term security of our country and the future of democracy everywhere.

Thursday 6 May 2021

Wednesday 1 April 2020

Wednesday 30 January 2019

Wednesday 16 January 2019

Wednesday 3 October 2018

Our cult of personality is leaving real life in the shade

By reducing politics to a celebrity obsession – from Johnson to Trump to Corbyn – the media misdirects and confuses us

What kind of people would you expect the newspapers to interview most? Those with the most to say, perhaps, or maybe those with the richest and weirdest experiences. Might it be philosophers, or detectives, or doctors working in war zones, refugees, polar scientists, street children, firefighters, base jumpers, activists, writers or free divers? No. It’s actors. I haven’t conducted an empirical study, but I would guess that between a third and a half of the major interviews in the newspapers feature people who make their living by adopting someone else’s persona and speaking someone else’s words.

This is such a bizarre phenomenon that, if it hadn’t crept up on us slowly, we would surely find it astounding. But it seems to me symbolic of the way the media works. Its problem runs deeper than fake news. What it offers is news about a fake world.

I am not proposing that the papers should never interview actors, or that they have no wisdom of their own to impart. But the remarkable obsession with this trade blots out other voices. One result is that an issue is not an issue until it has been voiced by an actor. Climate breakdown, refugees, human rights, sexual assault: none of these issues, it seems, can surface until they go Hollywood.

This is not to disparage the actors who have helped bring them to mainstream attention, least of all the brave and brilliant women who exposed Harvey Weinstein and popularised the #MeToo movement. But many other brave and brilliant women stood up to say the same thing – and, because they were not actors, remained unheard. The #MeToo movement is widely assumed to have begun a year ago, with Weinstein’s accusers. But it actually started in 2006, when the motto was coined by the activist Tarana Burke. She and the millions of others who tried to speak out were, neither literally nor metaphorically, in the spotlight.

At least actors serve everyone. But the next most-interviewed category, according to my unscientific survey, could be filed as “those who serve the wealthy”: restaurateurs, haute couturists, interior designers and the like, lionised and thrust into our faces as if we were their prospective clients. This is a world of make-believe, in which we are induced to imagine we are participants rather than mere gawpers.

The spotlight effect is bad enough on the culture pages. It’s worse when the same framing is applied to politics. Particularly during party conference season, but at other times of the year as well, public issues are cast as private dramas. Brexit, which is likely to alter the lives of everyone in Britain, is reduced to a story about whether or not Theresa May will keep her job. Who cares? Perhaps, by now, not even Theresa May.

Neither May nor Jeremy Corbyn can carry the weight of the personality cults that the media seeks to build around them. They are diffident and awkward in public, and appear to writhe in the spotlight. Both parties grapple with massive issues, and draw on the work of hundreds in formulating policy, tactics and presentation. Yet these huge and complex matters are reduced to the drama of one person’s struggle. Everyone, in the media’s viewfinder, becomes an actor. Reality is replaced by representation.

Even when political reporting is not reduced to personality, political photography is. An article might offer depth and complexity, but is illustrated with a photo of one of the 10 politicians whose picture must be attached to every news story. Where is the public clamour to see yet another image of May – let alone Boris Johnson? The pictures, like the actors, blot out our view of other people, and induce us to forget that these articles discuss the lives of millions, not the life of one.

The media’s failure of imagination and perspective is not just tiresome: it’s dangerous. There is a particular species of politics that is built entirely around personalities. It is a politics in which substance, evidence and analysis are replaced by symbols, slogans and sensation. It is called fascism. If you construct political narratives around the psychodramas of politicians, even when they don’t invite it, you open the way for those who can play this game more effectively.

Already this reporting style has led to the rise of people who, though they are not fascists, have demagogic tendencies. Johnson, Nigel Farage and Jacob Rees-Mogg are all, like Donald Trump, reality TV stars. The reality TV on which they feature is not The Apprentice, but Question Time and other news and current affairs programmes. In the media circus, the clowns have the starring roles. And clowns in politics are dangerous.

The spotlight effect allows the favoured few to set the agenda. Almost all the most critical issues remain in the darkness beyond the circle of light. Every day, thousands of pages are published and thousands of hours broadcast by the media. But scarcely any of this space and time is made available for the matters that really count: environmental breakdown, inequality, exclusion, the subversion of democracy by money. In a world of impersonation, we obsess about trivia. A story carried by BBC News last week was headlined “Meghan closes a car door”.

The BBC has just announced that two of its programmes will start covering climate change once a week. Given the indifference and sometimes outright hostility with which it has treated people trying to raise this issue over the past 20 years, this is progress. But business news, though less important than environmental collapse, is broadcast every minute, partly because it is treated as central by the people who run the media and partly because it is of pressing interest to those within the spotlight. We see what they want us to see. The rest remains in darkness.

The task of all journalists is to turn off the spotlight, roll up the blinds and see what’s lurking at the back of the room. There are some magnificent examples of how this can be done, such as the Windrush scandal reporting, by the Guardian’s Amelia Gentleman and others. This told the story of people who live far from where the spotlight falls. The articles were accompanied by pictures of victims rather than of the politicians who had treated them so badly: their tragedies were not supplanted by someone else’s drama. Yet these stories were told with such power that they forced even those within the spotlight to respond.

The task of all citizens is to understand what we are seeing. The world as portrayed is not the world as it is. The personification of complex issues confuses and misdirects us, ensuring that we struggle to comprehend and respond to our predicaments. This, it seems, is often the point.

Wednesday 25 July 2018

Wednesday 23 August 2017

Wednesday 12 April 2017

Finally, a breakthrough alternative to growth economics – the doughnut

So what are we going to do about it? This is the only question worth asking. But the answers appear elusive. Faced with a multifaceted crisis – the capture of governments by billionaires and their lobbyists, extreme inequality, the rise of demagogues, above all the collapse of the living world – those to whom we look for leadership appear stunned, voiceless, clueless. Even if they had the courage to act, they have no idea what to do.

The most they tend to offer is more economic growth: the fairy dust supposed to make all the bad stuff disappear. Never mind that it drives ecological destruction; that it has failed to relieve structural unemployment or soaring inequality; that, in some recent years, almost all the increment in incomes has been harvested by the top 1%. As values, principles and moral purpose are lost, the promise of growth is all that’s left.

You can see the effects in a leaked memo from the UK’s Foreign Office: “Trade and growth are now priorities for all posts … work like climate change and illegal wildlife trade will be scaled down.” All that counts is the rate at which we turn natural wealth into cash. If this destroys our prosperity and the wonders that surround us, who cares?

We cannot hope to address our predicament without a new worldview. We cannot use the models that caused our crises to solve them. We need to reframe the problem. This is what the most inspiring book published so far this year has done.

In Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist, Kate Raworth of Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute reminds us that economic growth was not, at first, intended to signify wellbeing. Simon Kuznets, who standardised the measurement of growth, warned: “The welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measure of national income.” Economic growth, he pointed out, measured only annual flow, rather than stocks of wealth and their distribution.

Raworth points out that economics in the 20th century “lost the desire to articulate its goals”. It aspired to be a science of human behaviour: a science based on a deeply flawed portrait of humanity. The dominant model – “rational economic man”, self-interested, isolated, calculating – says more about the nature of economists than it does about other humans. The loss of an explicit objective allowed the discipline to be captured by a proxy goal: endless growth.

The aim of economic activity, she argues, should be “meeting the needs of all within the means of the planet”. Instead of economies that need to grow, whether or not they make us thrive, we need economies that “make us thrive, whether or not they grow”. This means changing our picture of what the economy is and how it works.

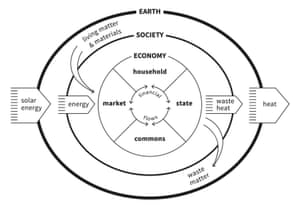

The central image in mainstream economics is the circular flow diagram. It depicts a closed flow of income cycling between households, businesses, banks, government and trade, operating in a social and ecological vacuum. Energy, materials, the natural world, human society, power, the wealth we hold in common … all are missing from the model. The unpaid work of carers – principally women – is ignored, though no economy could function without them. Like rational economic man, this representation of economic activity bears little relationship to reality.

So Raworth begins by redrawing the economy. She embeds it in the Earth’s systems and in society, showing how it depends on the flow of materials and energy, and reminding us that we are more than just workers, consumers and owners of capital.

The embedded economy ‘reminds us that we are more than just workers and consumers’. Source: Kate Raworth and Marcia Mihotich

This recognition of inconvenient realities then leads to her breakthrough: a graphic representation of the world we want to create. Like all the best ideas, her doughnut model seems so simple and obvious that you wonder why you didn’t think of it yourself. But achieving this clarity and concision requires years of thought: a great decluttering of the myths and misrepresentations in which we have been schooled.

The diagram consists of two rings. The inner ring of the doughnut represents a sufficiency of the resources we need to lead a good life: food, clean water, housing, sanitation, energy, education, healthcare, democracy. Anyone living within that ring, in the hole in the middle of the doughnut, is in a state of deprivation. The outer ring of the doughnut consists of the Earth’s environmental limits, beyond which we inflict dangerous levels of climate change, ozone depletion, water pollution, loss of species and other assaults on the living world.

The area between the two rings – the doughnut itself – is the “ecologically safe and socially just space” in which humanity should strive to live. The purpose of economics should be to help us enter that space and stay there.

As well as describing a better world, this model allows us to see, in immediate and comprehensible terms, the state in which we now find ourselves. At the moment we transgress both lines. Billions of people still live in the hole in the middle. We have breached the outer boundary in several places.

This model ‘allows us to see the state in which we now find ourselves’. Source: Kate Raworth and Christian Guthier/The Lancet Planetary Health

Such proposals are familiar; but without a new framework of thought, piecemeal solutions are unlikely to succeed. By rethinking economics from first principles, Raworth allows us to integrate our specific propositions into a coherent programme, and then to measure the extent to which it is realised.

I see her as the John Maynard Keynes of the 21st century: by reframing the economy, she allows us to change our view of who we are, where we stand, and what we want to be.

Now we need to turn her ideas into policy. Read her book, then demand that those who wield power start working towards its objectives: human prosperity within a thriving living world.

Saturday 11 June 2016

Economics Struggles to Cope With Reality

There are basically four different activities that all go by the name of macroeconomics. But they actually have relatively little to do with each other. Understanding the differences between them is helpful for understanding why debates about the business cycle tend to be so confused.

The first is what I call “coffee-house macro,” and it’s what you hear in a lot of casual discussions. It often revolves around the ideas of dead sages -- Friedrich Hayek, Hyman Minsky and John Maynard Keynes. It doesn’t involve formal models, but it does usually contain a hefty dose of political ideology.

The second is finance macro. This consists of private-sector economists and consultants who try to read the tea leaves on interest rates, unemployment, inflation and other indicators in order to predict the future of asset prices (usually bond prices). It mostly uses simple math, though advanced forecasting models are sometimes employed. It always includes a hefty dose of personal guesswork.

The third is academic macro. This traditionally involves professors making toy models of the economy -- since the early ’80s, these have almost exclusively been DSGE models (if you must ask, DSGE stands for dynamic stochastic general equilibrium). Though academics soberly insist that the models describe the deep structure of the economy, based on the behavior of individual consumers and businesses, most people outside the discipline who take one look at these models immediately think they’re kind of a joke. They contain so many unrealistic assumptions that they probably have little chance of capturing reality. Their forecasting performance is abysmal. Some of their core elements are clearly broken. Any rigorous statistical tests tend to reject these models instantly, because they always include a hefty dose of fantasy.

The fourth type I call Fed macro. The Federal Reserve uses an eclectic approach, involving both data and models. Sometimes the models are of the DSGE type, sometimes not. Fed macro involves taking data from many different sources, instead of the few familiar numbers like unemployment and inflation, and analyzing the information in a bunch of different ways. And it inevitably contains a hefty dose of judgment, because the Fed is responsible for making policy.

How can there be four very different activities that all go by the same name, and all claim to study and understand the same phenomena? My view is that academic macro has basically failed the other three.

Because academic macro models are so out of touch with reality, people in causal coffee-house discussions can’t refer to academic research to help make their points. Instead, they have to turn back to the old masters, who if vague and wordy were at least describing a world that had some passing resemblance to the economy we observe in our daily lives.

And because academic macro is so useless for forecasting -- including predicting the results of policy changes -- the financial industry can’t use it for practical purposes. I’ve talked to dozens of people in finance about why they don’t use DSGE models, and some have indeed tried to use them -- but they always dropped the models after poor performance.

Most unfortunately, the Fed has had to go it alone when studying how the macroeconomy really works. Regional Fed banks and the Federal Reserve Board function as macroeconomic think tanks, hiring top-level researchers to do the grubby data work and broad thinking that academia has decided is beneath it. But that leaves many of the field’s brightest minds locked in the ivory tower, playing with their toys.

Fortunately, this may be changing. Justin Wolfers, a University of Michigan professor and well-known economics commentator, recently presented a set of slides at a conference celebrating the career of Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist Olivier Blanchard. The slides, although short, are indicative of the sea change underway in the macro field.

Wolfers discusses how some of the main pillars of modern academic macro theory are now being challenged. The idea of “rational expectations,” which says that people on average use the correct mental model of the economy when they make their decisions, is being challenged by top professors, and many are looking at alternatives.

But that’s just the beginning -- far deeper changes may be in the offing. Wolfers suggested abandoning DSGE models, saying that they “haven’t worked.” That he said this at a conference honoring Blanchard, who was an important DSGE modeling pioneer, is a sign that the winds have shifted.

In place of the typical DSGE fare, Wolfers suggests that the new macroeconomics will focus on empirics and falsification -- in other words, looking at reality instead of making highly imaginative assumptions about it. He also says that macro will be fertilized by other disciplines, such as psychology and sociology, and will incorporate elements of behavioral economics.

I’d go even farther. I think the new macroeconomics won’t just be new kinds of models and a more empirical focus; it will redefine what “macroeconomics” even means.

As originally conceived, macro is about explaining national-level data series like employment, output and prices. Eventually, economists realized that to explain those things, they would need to understand the smaller pieces of the economy, such as consumer behavior or competition between companies. At first, they just imagined or postulated how these elements worked -- that’s the core of DSGE.

Economists now realize that consumers and businesses behave in ways that are much more complicated and difficult to understand. So there has been increased interest in what’s called “macro-focused micro” -- studies of businesses, competition, markets and individual behavior that have relevance for macro even though they weren’t traditionally included in the field. Examples of this would include studies of business dynamism, price adjustment, financial bubbles and differences between workers.

Let’s hope more and more macroeconomists focus on these things, instead of trying to make big, grandiose, but ultimately vacuous models of booms and recessions. When we understand the pieces of the economy better, we’ll have a much better chance of grasping the whole. If this continues, maybe the ivory tower will have more relevance for the Fed, the financial industry and maybe even for our coffee-house discussions.

Sunday 16 August 2015

England's Ashes Win - Despite, not Because

He who controls the past controls the future. He who controls the present controls the past.

Wednesday 18 September 2013

Cricket - How scarcity affects sportsmen

| |||

| Mental strength, Steve Waugh once told me, is about behaving the same way in everything you do at the crease, no matter how badly you're playing | |||

.