So what are we going to do about it? This is the only question worth asking. But the answers appear elusive. Faced with a multifaceted crisis – the capture of governments by billionaires and their lobbyists, extreme inequality, the rise of demagogues, above all the collapse of the living world – those to whom we look for leadership appear stunned, voiceless, clueless. Even if they had the courage to act, they have no idea what to do.

The most they tend to offer is more economic growth: the fairy dust supposed to make all the bad stuff disappear. Never mind that it drives ecological destruction; that it has failed to relieve structural unemployment or soaring inequality; that, in some recent years, almost all the increment in incomes has been harvested by the top 1%. As values, principles and moral purpose are lost, the promise of growth is all that’s left.

You can see the effects in a leaked memo from the UK’s Foreign Office: “Trade and growth are now priorities for all posts … work like climate change and illegal wildlife trade will be scaled down.” All that counts is the rate at which we turn natural wealth into cash. If this destroys our prosperity and the wonders that surround us, who cares?

We cannot hope to address our predicament without a new worldview. We cannot use the models that caused our crises to solve them. We need to reframe the problem. This is what the most inspiring book published so far this year has done.

In Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist, Kate Raworth of Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute reminds us that economic growth was not, at first, intended to signify wellbeing. Simon Kuznets, who standardised the measurement of growth, warned: “The welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measure of national income.” Economic growth, he pointed out, measured only annual flow, rather than stocks of wealth and their distribution.

Raworth points out that economics in the 20th century “lost the desire to articulate its goals”. It aspired to be a science of human behaviour: a science based on a deeply flawed portrait of humanity. The dominant model – “rational economic man”, self-interested, isolated, calculating – says more about the nature of economists than it does about other humans. The loss of an explicit objective allowed the discipline to be captured by a proxy goal: endless growth.

The aim of economic activity, she argues, should be “meeting the needs of all within the means of the planet”. Instead of economies that need to grow, whether or not they make us thrive, we need economies that “make us thrive, whether or not they grow”. This means changing our picture of what the economy is and how it works.

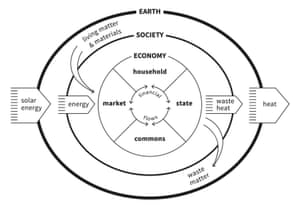

The central image in mainstream economics is the circular flow diagram. It depicts a closed flow of income cycling between households, businesses, banks, government and trade, operating in a social and ecological vacuum. Energy, materials, the natural world, human society, power, the wealth we hold in common … all are missing from the model. The unpaid work of carers – principally women – is ignored, though no economy could function without them. Like rational economic man, this representation of economic activity bears little relationship to reality.

So Raworth begins by redrawing the economy. She embeds it in the Earth’s systems and in society, showing how it depends on the flow of materials and energy, and reminding us that we are more than just workers, consumers and owners of capital.

The embedded economy ‘reminds us that we are more than just workers and consumers’. Source: Kate Raworth and Marcia Mihotich

This recognition of inconvenient realities then leads to her breakthrough: a graphic representation of the world we want to create. Like all the best ideas, her doughnut model seems so simple and obvious that you wonder why you didn’t think of it yourself. But achieving this clarity and concision requires years of thought: a great decluttering of the myths and misrepresentations in which we have been schooled.

The diagram consists of two rings. The inner ring of the doughnut represents a sufficiency of the resources we need to lead a good life: food, clean water, housing, sanitation, energy, education, healthcare, democracy. Anyone living within that ring, in the hole in the middle of the doughnut, is in a state of deprivation. The outer ring of the doughnut consists of the Earth’s environmental limits, beyond which we inflict dangerous levels of climate change, ozone depletion, water pollution, loss of species and other assaults on the living world.

The area between the two rings – the doughnut itself – is the “ecologically safe and socially just space” in which humanity should strive to live. The purpose of economics should be to help us enter that space and stay there.

As well as describing a better world, this model allows us to see, in immediate and comprehensible terms, the state in which we now find ourselves. At the moment we transgress both lines. Billions of people still live in the hole in the middle. We have breached the outer boundary in several places.

This model ‘allows us to see the state in which we now find ourselves’. Source: Kate Raworth and Christian Guthier/The Lancet Planetary Health

An economics that helps us to live within the doughnut would seek to reduce inequalities in wealth and income. Wealth arising from the gifts of nature would be widely shared. Money, markets, taxation and public investment would be designed to conserve and regenerate resources rather than squander them. State-owned banks would invest in projects that transform our relationship with the living world, such as zero-carbon public transport and community energy schemes. New metrics would measure genuine prosperity, rather than the speed with which we degrade our long-term prospects.

Such proposals are familiar; but without a new framework of thought, piecemeal solutions are unlikely to succeed. By rethinking economics from first principles, Raworth allows us to integrate our specific propositions into a coherent programme, and then to measure the extent to which it is realised.

I see her as the John Maynard Keynes of the 21st century: by reframing the economy, she allows us to change our view of who we are, where we stand, and what we want to be.

Now we need to turn her ideas into policy. Read her book, then demand that those who wield power start working towards its objectives: human prosperity within a thriving living world.

Such proposals are familiar; but without a new framework of thought, piecemeal solutions are unlikely to succeed. By rethinking economics from first principles, Raworth allows us to integrate our specific propositions into a coherent programme, and then to measure the extent to which it is realised.

I see her as the John Maynard Keynes of the 21st century: by reframing the economy, she allows us to change our view of who we are, where we stand, and what we want to be.

Now we need to turn her ideas into policy. Read her book, then demand that those who wield power start working towards its objectives: human prosperity within a thriving living world.