'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Saturday, 2 December 2023

Monday, 11 September 2023

Friday, 23 June 2023

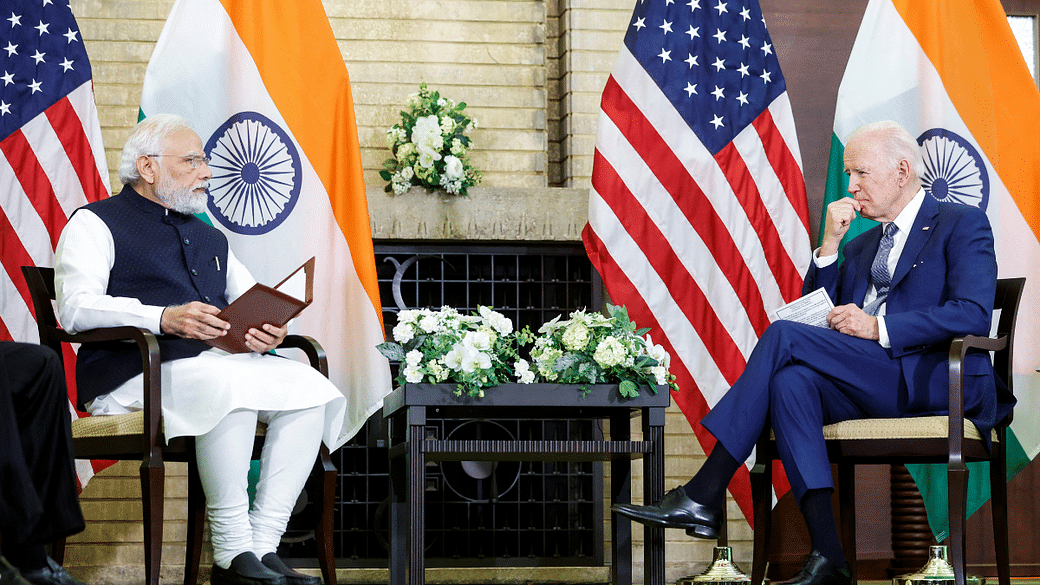

Attacking Modi in US shows IAMC using Indian Muslims as pawns

While PM Modi’s state visit to the US is being noticed across world capitals, his opponents in the US are busy doing what they love most — criticising him for his human rights record and accusing his government of suppressing dissent and implementing discriminatory policies against Muslims and other minority groups.

It is not uncommon to witness certain groups initiating campaigns on foreign soil, portraying a narrative of persecution of Indian Muslims. Raising one’s voice for human rights is indeed a crucial and meaningful endeavour. However, challenges arise when human rights issues are exploited as a tool for propaganda, distorting and manipulating the truth about a nation.

Being an Indian Pasmanda Muslim, I frequently witness the propagation of these false narratives against my homeland. Hence it is my sincere duty to raise my voice against them. India, as a nation, not only embraces the homeland of over one billion Hindus but also stands as a diverse abode for 200 million Muslims, 28 million Christians, 21 million Sikhs, 12 million Buddhists, 4.45 million Jains, and countless others.

It is truly disheartening to witness the portrayal of a nation with such a rich and inclusive history as a place where Muslims are purportedly on the verge of facing genocide. Such narratives often rely on select stories, and it is concerning that the Western media often accepts them without delving into the ground realities and comprehending the policies implemented by the Indian State. It is important for such storytellers to seek a more nuanced understanding by examining the comprehensive picture and taking into account the complexities and intricacies.

To begin with, organisations like the Indian American Muslim Council (IAMC) claim to represent the voice of Indian Muslims. However, they frequently disseminate false and misleading information through their tweets. Moreover, there have been instances where their tweets have been provocative and inflammatory. For instance, they tweeted an unsubstantiated claim stating that all victims in the Delhi riots were Muslims. This organisation has scheduled a protest outside the White House, which raises legitimate questions about their true intentions– do they genuinely prioritise the welfare of Indian Muslims or have ulterior motives and agendas at play?

Indian Muslims, stop being a pawn of anti-India forces

It is high time the Western media and geopolitical interest groups refrain from exploiting the term “Indian Muslims” for their own agendas. As for Indian Muslims, it is important that they themselves comprehend how they are being manipulated as pawns on the global stage, working against their own nation’s interests. It is imperative for them to speak out against these false narratives. We lead peaceful lives, enjoy equal rights and opportunities, have the freedom to practise our religion and make choices, and receive our fair share of benefits from welfare schemes run by the government. Our future is intertwined with our nation’s interests, and anything that generates an anti-India narrative ultimately goes against our own well-being.

Organisations like IAMC, which have no genuine connection with Indian Muslims, falsely claim to represent us while using us as pawns to further their own agendas. It is essential for Muslim intellectuals to see through these manipulations. First, the Muslim community was exploited as a mere vote bank. Now there is a risk of them being used as tools to perpetuate an anti-India narrative.

Examine Western media bias

The Western media has consistently portrayed a negative image of India since its Independence. Interestingly, failed states and countries in the middle of civil wars receive minimal attention.

PM Modi, during a national executive meeting of the BJP, clearly expressed a desire for outreach to the Muslim community, acknowledging that many within the community wish to connect with the party. He emphasised the importance of engaging with not only the economically disadvantaged Pasmanda and Bora Muslims but also educated Muslims. Previously, Modi has highlighted the integration of Pasmanda Muslims with the BJP, urging positive programmes to attract their support.

When BJP leaders have made objectionable statements about Muslims, leading to a tense atmosphere in the country, the party has taken disciplinary action against them too. Under the Modi government, a significant number of minority students have received education scholarships, surpassing previous administrations. Muslim women beneficiaries have expressed their gratitude for various government schemes, such as free ration, the abolition of instant divorce practices, free Covid vaccinations, Ujjawala cooking gas connections, and free housing, which have improved their lives. These initiatives demonstrate efforts to ensure the inclusion and well-being of Muslim communities in India.

It is important to address how Western media and human rights organisations often depict Indian Muslims as ostracised and living in a genocidal environment. For instance, the IAMC played a significant role in lobbying against India in 2019, leading to US Commission on International Religious Freedom recommending India to be blacklisted. For four consecutive years, the USCIRF has advised the US administration to designate India as a “Country of Particular Concern.” Ironically, in their assessments, they did not take into account the reality experienced by Indian Muslims. According to Pew Research, 98 per cent of Indian Muslims are free to practise their religion without hindrance. This stark contrast highlights the disconnect between the exaggerated narratives and the ground realities of religious freedom for Indian Muslims.

Don’t weaponise discourse

In their commentary, Western media and human rights organisations fail to carry voices of ordinary Indian Muslims. Providing a comprehensive and accurate understanding, based on data, helps avoid weaponisation of narratives that serve geopolitical interests.

Data often highlights the disparities in perceptions of discrimination among different communities. According to the Pew study, 80 per cent of African-Americans, 46 per cent of Hispanic Americans, and 42 per cent of Asian Americans stated they experience “a lot of discrimination” in the US. In comparison, 24 per cent of Indian Muslims say that there is widespread discrimination against them in India. Furthermore, the majority of Indian Muslims expressed pride in their Indian identity.

These statistics challenge the narrative of widespread persecution of Indian Muslims within their own nation. It raises the question of whether the same level of scrutiny should be applied to the United States, considering the reported discrimination experienced by minority communities there. It prompts us to reflect on whether the labelling of human rights violations should be applied selectively. And what explains the timing of such mongering — just before a State head is about to visit the country.

Sunday, 2 April 2023

Wednesday, 15 March 2023

Tuesday, 20 December 2022

Sunday, 18 December 2022

Why were the media hypnotised by Sam Bankman-Fried?

So Sam Bankman-Fried (henceforth SBF) was eventually arrested at his multimillion-dollar residence in the Bahamas, a tax haven with nice beaches attached. The only mystery about this was the unconscionable length of time that it took the Bahamian authorities to measure him for handcuffs. The police said that he was arrested at the request of US legal authorities for “financial offences” under US and Bahamian laws connected with the FTX cryptocurrency exchange that he co-founded in 2019 and Alameda Research, a hedge fund that he set up in 2017. On Tuesday, a local court denied him bail, which suggests that an extradition request from the US will be granted and he will soon be appearing in a New York courtroom.

The grisly details of what SBF is alleged to be guilty of will emerge in forthcoming criminal proceedings. But already expectations are high: Amazon has announced that it is working on a series about the scandal in partnership with the Russo brothers, the makers of Marvel movies.

For the moment, though, a brief outline will have to do. FTX was a cryptocurrency exchange that provided an easy way for people to buy and sell these virtual currencies. Many people had invested billions of “real” money in it to facilitate their participation in the crypto casino. But in early November, rumours of problems with FTX surfaced after Binance, another crypto exchange, dramatically refused to bail it out, citing “corporate due diligence” and reports of “mishandled customer funds”.

There then followed, as the night the day, a run on FTX, as panicking investors tried to withdraw their money, which in turn led to its insolvency and a filing for bankruptcy. The big puzzle, though, was why couldn’t FTX have just given its investors their money back? The answer appears to be that it wasn’t there; in some way, SBF’s hedge fund had been treating FTX as its piggy bank, possibly even playing the hedge fund market with investors’ money.

The thought SBF might be as manipulative as any oil mogul or tobacco executive never occurred to the poor dears

Once it was clear that this particular game was up, SBF then embarked on an astonishing apology tour on every media outlet he could find. In almost every interview he was touchingly apologetic while at the same time maintaining that he had no knowledge of potentially fraudulent activities at his own company, including using billions of dollars of customers’ deposits as collateral for loans for other purposes. He had, he explained ruefully, been out of his depth. On some occasions, he also seemed to be trying to deflect blame on to Caroline Ellison, the former CEO of his other company, Alameda Research.

The biggest question prompted by this apology tour is: why did so many apparently serious media outfits let him get away with it? The interview questions were often softball ones, occasionally toe-curlingly so. Some interviewers confessed apologetically that they knew nothing about the complex businesses he had run and allowed themselves to be bemused by the incomprehensible bullshit he was emitting. Often, they seemed hypnotised, as many otherwise sensible people had been before the crash, by this tech wunderkind with big hair and baggy shorts who had, until recently, been promising to give away his phenomenal wealth to good causes, while in fact he had seemingly been presiding over the vaporisation of billions of dollars of other people’s savings.

But this embarrassing failure of mainstream media was really just the encore to an even bigger failure – their wilful blindness to what had been going on while SBF was in his prime. It turned out that earlier in the year the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) had written to FTX seeking to determine if the company was as flaky as some observers (mainly on the web) had suspected. As Cory Doctorow pointed out, the SEC never got an answer, because eight US lawmakers – four Republicans and four Democrats – wrote a letter to the SEC chairman demanding that he back off. And five of these eight, according to Doctorow, had received substantial case donations from SBF, his employees, affiliated businesses or political action committees.

There was a real story here, in other words, long before FTX imploded. But it wasn’t told because the mainstream media were so invested in the founder-worship that is the curse of the tech industry, not to mention some of those who cover it. The thought that “the poster child for the libertarian ethos that crypto profits accrued to those most capable”, as one commentator described SBF, might be as politically manipulative as any oil mogul or tobacco executive never occurred to the poor dears. Sometimes, societies get the mainstream media they deserve.

Monday, 28 February 2022

Wednesday, 5 January 2022

Watching Don’t Look Up made me see my whole life of campaigning flash before me

Cate Blanchett, Tyler Perry, Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence in Don't Look Up. Photograph: Niko Tavernise/AP

Cate Blanchett, Tyler Perry, Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence in Don't Look Up. Photograph: Niko Tavernise/APNo wonder journalists have slated it. They’ve produced a hundred excuses not to watch the climate breakdown satire Don’t Look Up: it’s “blunt”, it’s “shrill”, it’s “smug”. But they will not name the real problem: it’s about them. The movie is, in my view, a powerful demolition of the grotesque failures of public life. And the sector whose failures are most brutally exposed is the media.

While the film is fast and funny, for me, as for many environmental activists and climate scientists, it seemed all too real. I felt as if I were watching my adult life flash past me. As the scientists in the film, trying to draw attention to the approach of a planet-killing comet, bashed their heads against the Great Wall of Denial erected by the media and sought to reach politicians with 10-second attention spans, all the anger and frustration and desperation I’ve felt over the years boiled over.

Above all, when the scientist who had discovered the comet was pushed to the bottom of the schedule by fatuous celebrity gossip on a morning TV show and erupted in fury, I was reminded of my own mortifying loss of control on Good Morning Britain in November. It was soon after the Cop26 climate conference in Glasgow, where we had seen the least serious of all governments (the UK was hosting the talks) failing to rise to the most serious of all issues. I tried, for the thousandth time, to explain what we are facing, and suddenly couldn’t hold it in any longer. I burst into tears on live TV.

I still feel deeply embarrassed about it. The response on social media, like the response to the scientist in the film, was vituperative and vicious. I was faking. I was hysterical. I was mentally ill. But, knowing where we are and what we face, seeing the indifference of those who wield power, seeing how our existential crisis has been marginalised in favour of trivia and frivolity, I now realise that there would be something wrong with me if I hadn’t lost it.

‘I tried, for the thousandth time, to explain what we are facing, and suddenly couldn’t hold it in any longer.’ Photograph: George Monbiot crying screengrab/Good Morning Britain

‘I tried, for the thousandth time, to explain what we are facing, and suddenly couldn’t hold it in any longer.’ Photograph: George Monbiot crying screengrab/Good Morning BritainIn fighting any great harm, in any age, we find ourselves confronting the same forces: distraction, denial and delusion. Those seeking to sound the alarm about the gathering collapse of our life-support systems soon hit the barrier that stands between us and the people we are trying to reach, a barrier called the media. With a few notable exceptions, the sector that should facilitate communication thwarts it.

It’s not just its individual stupidities that have become inexcusable, such as the platforms repeatedly given to climate deniers. It is the structural stupidity to which the media are committed. It’s the anti-intellectualism, the hostility to new ideas and aversion to complexity. It’s the absence of moral seriousness. It’s the vacuous gossip about celebrities and consumables that takes precedence over the survival of life on Earth. It’s the obsession with generating noise, regardless of signal. It’s the reflexive alignment with the status quo, whatever it may be. It’s the endless promotion of the views of the most selfish and antisocial people, and the exclusion of those who are trying to defend us from catastrophe, on the grounds that they are “worthy”, “extreme” or “mad” (I hear from friends in the BBC that these terms are still used there to describe environmental activists).

Even when these merchants of distraction do address the issue, they tend to shut out the experts and interview actors, singers and other celebs instead. The media’s obsession with actors vindicates Guy Debord’s predictions in his book The Society of the Spectacle, published in 1967. Substance is replaced by semblance, as even the most serious issues must now be articulated by people whose work involves adopting someone else’s persona and speaking someone else’s words. Then the same media, having turned them into spokespeople, attack these actors as hypocrites for leading a profligate lifestyle.

Similarly, it’s not just the individual failures by governments at Glasgow and elsewhere that have become inexcusable, but the entire framework of negotiations. As crucial Earth systems might be approaching their tipping point, governments still propose to address the issue with tiny increments of action, across decades. It’s as if, in 2008, when Lehman Brothers collapsed and the global financial system began to sway, governments had announced that they would bail out the banks at the rate of a few million pounds a day between then and 2050. The system would have collapsed 40 years before their programme was complete. Our central, civilisational question, I believe, is this: why do nations scramble to rescue the banks but not the planet?

So, as we race towards Earth system collapse, trying to raise the alarm feels like being trapped behind a thick plate of glass. People can see our mouths opening and closing, but they struggle to hear what we are saying. As we frantically bang the glass, we look ever crazier. And feel it. The situation is genuinely maddening. I’ve been working on these issues since I was 22, and full of confidence and hope. I’m about to turn 59, and the confidence is turning to cold fear, the hope to horror. As manufactured indifference ensures that we remain unheard, it becomes ever harder to know how to hold it together. I cry most days now.

Thursday, 10 June 2021

Thursday, 3 June 2021

Tuesday, 1 June 2021

If the Wuhan lab-leak hypothesis is true, expect a political earthquake

Thomas Frank in The Guardian

There was a time when the Covid pandemic seemed to confirm so many of our assumptions. It cast down the people we regarded as villains. It raised up those we thought were heroes. It prospered people who could shift easily to working from home even as it problematized the lives of those Trump voters living in the old economy.

Like all plagues, Covid often felt like the hand of God on earth, scourging the people for their sins against higher learning and visibly sorting the righteous from the unmasked wicked. “Respect science,” admonished our yard signs. And lo!, Covid came and forced us to do so, elevating our scientists to the highest seats of social authority, from where they banned assembly, commerce, and all the rest.

We cast blame so innocently in those days. We scolded at will. We knew who was right and we shook our heads to behold those in the wrong playing in their swimming pools and on the beach. It made perfect sense to us that Donald Trump, a politician we despised, could not grasp the situation, that he suggested people inject bleach, and that he was personally responsible for more than one super-spreading event. Reality itself punished leaders like him who refused to bow to expertise. The prestige news media even figured out a way to blame the worst death tolls on a system of organized ignorance they called “populism.”

But these days the consensus doesn’t consense quite as well as it used to. Now the media is filled with disturbing stories suggesting that Covid might have come — not from “populism” at all, but from a laboratory screw-up in Wuhan, China. You can feel the moral convulsions beginning as the question sets in: What if science itself is in some way culpable for all this?

*

I am no expert on epidemics. Like everyone else I know, I spent the pandemic doing as I was told. A few months ago I even tried to talk a Fox News viewer out of believing in the lab-leak theory of Covid’s origins. The reason I did that is because the newspapers I read and the TV shows I watched had assured me on many occasions that the lab-leak theory wasn’t true, that it was a racist conspiracy theory, that only deluded Trumpists believed it, that it got infinite pants-on-fire ratings from the fact-checkers, and because (despite all my cynicism) I am the sort who has always trusted the mainstream news media.

My own complacency on the matter was dynamited by the lab-leak essay that ran in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists earlier this month; a few weeks later everyone from Doctor Fauci to President Biden is acknowledging that the lab-accident hypothesis might have some merit. We don’t know the real answer yet, and we probably will never know, but this is the moment to anticipate what such a finding might ultimately mean. What if this crazy story turns out to be true?

The answer is that this is the kind of thing that could obliterate the faith of millions. The last global disaster, the financial crisis of 2008, smashed people’s trust in the institutions of capitalism, in the myths of free trade and the New Economy, and eventually in the elites who ran both American political parties.

In the years since (and for complicated reasons), liberal leaders have labored to remake themselves into defenders of professional rectitude and established legitimacy in nearly every field. In reaction to the fool Trump, liberalism made a sort of cult out of science, expertise, the university system, executive-branch “norms,” the “intelligence community,” the State Department, NGOs, the legacy news media, and the hierarchy of credentialed achievement in general.

Now here we are in the waning days of Disastrous Global Crisis #2. Covid is of course worse by many orders of magnitude than the mortgage meltdown — it has killed millions and ruined lives and disrupted the world economy far more extensively. Should it turn out that scientists and experts and NGOs, etc. are villains rather than heroes of this story, we may very well see the expert-worshiping values of modern liberalism go up in a fireball of public anger.

Consider the details of the story as we have learned them in the last few weeks:

- Lab leaks happen. They aren’t the result of conspiracies: “a lab accident is an accident,” as Nathan Robinson points out; they happen all the time, in this country and in others, and people die from them.

- There is evidence that the lab in question, which studies bat coronaviruses, may have been conducting what is called “gain of function” research, a dangerous innovation in which diseases are deliberately made more virulent. By the way, right-wingers didn’t dream up “gain of function”: all the cool virologists have been doing it (in this country and in others) even as the squares have been warning against it for years.

- There are strong hints that some of the bat-virus research at the Wuhan lab was funded in part by the American national-medical establishment — which is to say, the lab-leak hypothesis doesn’t implicate China alone.

- There seem to have been astonishing conflicts of interest among the people assigned to get to the bottom of it all, and (as we know from Enron and the housing bubble) conflicts of interest are always what trip up the well-credentialed professionals whom liberals insist we must all heed, honor, and obey.

- The news media, in its zealous policing of the boundaries of the permissible, insisted that Russiagate was ever so true but that the lab-leak hypothesis was false false false, and woe unto anyone who dared disagree. Reporters gulped down whatever line was most flattering to the experts they were quoting and then insisted that it was 100% right and absolutely incontrovertible — that anything else was only unhinged Trumpist folly, that democracy dies when unbelievers get to speak, and so on.

- The social media monopolies actually censored posts about the lab-leak hypothesis. Of course they did! Because we’re at war with misinformation, you know, and people need to be brought back to the true and correct faith — as agreed upon by experts.

“Let us pray, now, for science,” intoned a New York Times columnist back at the beginning of the Covid pandemic. The title of his article laid down the foundational faith of Trump-era liberalism: “Coronavirus is What You Get When You Ignore Science.”

Ten months later, at the end of a scary article about the history of “gain of function” research and its possible role in the still ongoing Covid pandemic, Nicholson Baker wrote as follows: “This may be the great scientific meta-experiment of the 21st century. Could a world full of scientists do all kinds of reckless recombinant things with viral diseases for many years and successfully avoid a serious outbreak? The hypothesis was that, yes, it was doable. The risk was worth taking. There would be no pandemic.”

Except there was. If it does indeed turn out that the lab-leak hypothesis is the right explanation for how it began — that the common people of the world have been forced into a real-life lab experiment, at tremendous cost — there is a moral earthquake on the way.

Because if the hypothesis is right, it will soon start to dawn on people that our mistake was not insufficient reverence for scientists, or inadequate respect for expertise, or not enough censorship on Facebook. It was a failure to think critically about all of the above, to understand that there is no such thing as absolute expertise. Think of all the disasters of recent years: economic neoliberalism, destructive trade policies, the Iraq War, the housing bubble, banks that are “too big to fail,” mortgage-backed securities, the Hillary Clinton campaign of 2016 — all of these disasters brought to you by the total, self-assured unanimity of the highly educated people who are supposed to know what they’re doing, plus the total complacency of the highly educated people who are supposed to be supervising them.

Then again, maybe I am wrong to roll out all this speculation. Maybe the lab-leak hypothesis will be convincingly disproven. I certainly hope it is.

But even if it inches closer to being confirmed, we can guess what the next turn of the narrative will be. It was a “perfect storm,” the experts will say. Who coulda known? And besides (they will say), the origins of the pandemic don’t matter any more. Go back to sleep.

Friday, 15 January 2021

Conspiracy theorists destroy a rational society: resist them

John Thornhill in The FT

Buzz Aldrin’s reaction to the conspiracy theorist who told him the moon landings never happened was understandable, if not excusable. The astronaut punched him in the face.

Few things in life are more tiresome than engaging with cranks who refuse to accept evidence that disproves their conspiratorial beliefs — even if violence is not the recommended response. It might be easier to dismiss such conspiracy theorists as harmless eccentrics. But while that is tempting, it is in many cases wrong.

As we have seen during the Covid-19 pandemic and in the mob assault on the US Congress last week, conspiracy theories can infect the real world — with lethal effect. Our response to the pandemic will be undermined if the anti-vaxxer movement persuades enough people not to take a vaccine. Democracies will not endure if lots of voters refuse to accept certified election results. We need to rebut unproven conspiracy theories. But how?

The first thing to acknowledge is that scepticism is a virtue and critical scrutiny is essential. Governments and corporations do conspire to do bad things. The powerful must be effectively held to account. The US-led war against Iraq in 2003, to destroy weapons of mass destruction that never existed, is a prime example.

The second is to re-emphasise the importance of experts, while accepting there is sometimes a spectrum of expert opinion. Societies have to base decisions on experts’ views in many fields, such as medicine and climate change, otherwise there is no point in having a debate. Dismissing the views of experts, as Michael Gove famously did during the Brexit referendum campaign, is to erode the foundations of a rational society. No sane passenger would board an aeroplane flown by an unqualified pilot.

In extreme cases, societies may well decide that conspiracy theories are so harmful that they must suppress them. In Germany, for example, Holocaust denial is a crime. Social media platforms that do not delete such content within 24 hours of it being flagged are fined.

In Sweden, the government is even establishing a national psychological defence agency to combat disinformation. A study published this week by the Oxford Internet Institute found “computational propaganda” is now being spread in 81 countries.

Viewing conspiracy theories as political propaganda is the most useful way to understand them, according to Quassim Cassam, a philosophy professor at Warwick university who has written a book on the subject. In his view, many conspiracy theories support an implicit or explicit ideological goal: opposition to gun control, anti-Semitism or hostility to the federal government, for example. What matters to the conspiracy theorists is not whether their theories are true, but whether they are seductive.

So, as with propaganda, conspiracy theories must be as relentlessly opposed as they are propagated.

That poses a particular problem when someone as powerful as the US president is the one shouting the theories. Amid huge controversy, Twitter and Facebook have suspended Donald Trump’s accounts. But Prof Cassam says: “Trump is a mega disinformation factory. You can de-platform him and address the supply side. But you still need to address the demand side.”

On that front, schools and universities should do more to help students discriminate fact from fiction. Behavioural scientists say it is more effective to “pre-bunk” a conspiracy theory — by enabling people to dismiss it immediately — than debunk it later. But debunking serves a purpose, too.

As of 2019, there were 188 fact-checking sites in more than 60 countries. Their ability to inject facts into any debate can help sway those who are curious about conspiracy theories, even if they cannot convince true believers.

Under intense public pressure, social media platforms are also increasingly filtering out harmful content and nudging users towards credible sources of information, such as medical bodies’ advice on Covid.

Some activists have even argued for “cognitive infiltration” of extremist groups, suggesting that government agents should intervene in online chat rooms to puncture conspiracy theories. That may work in China but is only likely to backfire in western democracies, igniting an explosion of new conspiracy theories.

Ultimately, we cannot reason people out of beliefs that they have not reasoned themselves into. But we can, and should, punish those who profit from harmful irrationality. There is a tried-and-tested method of countering politicians who peddle and exploit conspiracy theories: vote them out of office.

Saturday, 9 January 2021

Sunday, 15 September 2019

BBC to New York Times – Why Indian governments have always been wary of foreign press

P

PAn urban legend goes like this – when Indira Gandhi was assassinated, her son Rajiv Gandhi wanted to know if it had been confirmed by the BBC. Until the BBC broadcast the news, it could be dismissed as a rumour.

That was then. Today, fanboys of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s strident nationalism, accuse the venerable BBC of peddling fake news.

The Western gaze on India is acceptable only if it is about yoga and ayurveda, not Kashmir. Curiously, the Indira Gandhi regime often accused the BBC of being an extension of the Cold War ‘foreign hand’ out to undermine India. Today, the Modi ecosystem accuses it of being anti-Hindu.

The government and the BJP want to actively fix this – with both the carrot and the stick. On the one hand, Hindu groups are protesting outside The Washington Post office in the US, and on the other, NSA Ajit Doval is feting foreign journalists and RSS’ Mohan Bhagwat is scheduling meetings with them.

Be it India or China or Russia – you can be sure that when a country accuses the foreign media of biased coverage, it has something it wants to hide. It’s a good barometer of what’s going on inside. That is why restricting access is common practice.

Fences & restrictions

Foreign journalists can visit Assam only after taking permission from the Ministry of External Affairs, which consults the Ministry of Home Affairs before issuing a permit. In Jammu and Kashmir, things are no better. A circular from the Ministry of External Affairs says permission has to be sought by foreign journalists eight weeks before the date of visit. From May 2018 to January 2019, only two foreign journalists had got this permission.

That’s not all. Media outlets such as the BBC and Al Jazeera have been trolled on social media for their coverage of Kashmir after the abrogation of Article 370, with the Modi government jumping to say their footage was fabricated.

The criticism has been echoed even by pro-government TV anchors and social media warriors (some like Shekhar Kapur who have justifiably picked on the BBC’s habit of referring to Jammu and Kashmir as Indian-occupied Kashmir).

But India Today did a detailed forensic analysis to show the BBC video was anything but “fake news”. The BBC has also stood by its video (initially reported by Reuters) showing protestors marching on the streets with Article 370 placards and tear gas being used to disperse protests. “A protest the Indian government said did not happen,” @BBCWorld said.

Always on high alert

India’s sensitivity to how the BBC, in particular, sees it, is not new. John Elliott, who has reported on India, from India, for 25 years, told The Print: “India always seems to want international approval and praise, indicating it is not yet fully confident on the world stage. That leads to extreme sensitivity over negative comment, maybe even more so under Prime Minister Narendra Modi for whom international recognition is a primary aim.”

It doesn’t take much to raise India’s hackles. In 1970, when French maestro Louis Malle’s documentary series Phantom India was shown on the BBC, it resulted in the closure of the BBC’s office in Delhi for two years and the repatriation of its news correspondent Ronald Robson. All because, even though the series was well received by British critics, Indians were upset about Malle’s inclusion in the first programme of ”a few shots of people sleeping on the pavements of Calcutta”. This was the “export of Indian poverty” argument that Nargis Dutt used about Satyajit Ray in 1980, with her now-famous quote: “I don’t believe Mr Satyajit Ray cannot be criticised. He is only a Ray, not the Sun.”

As Sunil Khilnani notes in his book, Incarnations: India in 50 Lives, Nargis felt Ray’s movies were popular in the West because “people there want to see India in an abject condition”. She wanted him to show “modern India”, not merely project “Indian poverty abroad”.

Thin-skinned governments

Of late, though, it is India’s fractious politics, which has made Indian governments extremely thin-skinned. This too has a history. Mark Tully, who became BBC’s Delhi bureau chief after it was allowed to return to India in 1972, fell afoul of prime minister Indira Gandhi in 1975 during the Emergency. As he says in this 2018 interview, at the time it was said he had reported that one of the senior-most cabinet ministers had resigned from her government in protest against the Emergency. Then information and broadcasting minister Inder Gujral stood up for him telling Mohammed Yunus (part of Indira Gandhi’s ‘kitchen cabinet’) that he had checked with the monitoring service and there was no evidence of Tully having said so.

Tully says Yunus told Gujral: ”I want you to arrest him, take his trousers down, and give him a beating and then put him in jail. Those were roughly the words I have recorded in the interview and it is also transcribed in a book I wrote with Zareer Masani called Raj to Rajiv. So, I discovered 18 months after the Emergency that I had had a lucky escape.”

In 2002, Time magazine’s Alex Perry had to face questioning over alleged passport irregularities after he wrote the widely quoted cover story on then prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, wherein he said Vajpayee “fell asleep in cabinet meetings, was prone to ‘interminable silences’ and enjoyed a nightly whisky”. Although there was talk of Perry being thrown out of India, much like Tully, it didn’t happen. Perry left as Delhi bureau chief much later, in 2006. Now a well-known writer, he declined to comment for this story to ThePrint, calling it “old history”.

Rot within

Nothing is really history in Indian politics, where personalities, issues, and allegations tend to be recycled. The New York Times is routinely accused of an anti-India bias – whether it was the diplomatic immunity of IFS officer Devyani Khobragade then or the Indian government’s abrogation of Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir now.

As veteran journalist Mannika Chopra points out to ThePrint, Indian politicians have always been wary of the foreign press. “Under Indira Gandhi, it was difficult for foreign correspondents to report on Kashmir or the northeast. Or for visiting reporters to get visas. But the situation has changed. In India today, it would be fair to say the domestic media has, by and large, been won over by the current government, and those who haven’t are wary of speaking out. Independent voices are few. Political journalism has also changed. There are no hard-hitting investigations,” she said.

She points out that it has been left to the foreign press to present a counter-narrative, a dialogue independent of ideological blinkers and pressures. “As for the media within, it is all about being not merely anti-national but also supra-national.”

Elliott jokes that he wished Britain had some of the same sensitivity over international comments on Brexit so ”that we realised how the world sees our descent into constitutional and political chaos”. But perhaps not, given that India’s outrage can span the spectrum—from a BBC interview with a jubilant Jagjit Singh Chauhan in 1984 after Indira Gandhi’s death (as noted by scholar Suzanne Franks) to Jade Goody’s racist slurs in 2007 again then Celebrity Big Brother contestant Shilpa Shetty.

In India’s Republic of Easy Offence, the bar for public anger and government censure is quite low.

Wednesday, 17 April 2019

'Calling bullshit': the college class on how not to be duped by the news

To prepare themselves for future success in the American workforce, today’s college students are increasingly choosing courses in business, biomedical science, engineering, computer science, and various health-related disciplines.

These classes are bound to help undergraduates capitalize on the “college payoff”, but chances are good that none of them comes with a promise of this magnitude: “We will be astonished if these skills [learned in this course] do not turn out to be the most useful and most broadly applicable of those that you acquire during the course of your college education.”

Sound like bullshit? If so, there’s no better way to detect it than to consider the class that makes the claim. Calling Bullshit: Data Reasoning in a Digital World, designed and co-taught by the University of Washington professors Jevin West and Carl Bergstrom, begins with a premise so obvious we barely lend it the attention it deserves: “Our world is saturated with bullshit.” And so, every week for 12 weeks, the professors expose “one specific facet of bullshit”, doing so in the explicit spirit of resistance. “This is,” they explain, “our attempt to fight back.”

The problem of bullshit transcends political bounds, the class teaches. The proliferation of bullshit, according to West and Bergstrom, is “not a matter of left- or rightwing ideology; both sides of the aisle have proven themselves facile at creating and spreading bullshit. Rather (and at the risk of grandiose language) adequate bullshit detection strikes us as essential to the survival of liberal democracy.” They make it a point to stress that they began to work on the syllabus for this class back in 2015 – it’s not, they clarify, “a swipe at the Trump administration”.

There has been considerable debate over what exactly qualifies as bullshit

Academia being what it is (a place where everything is contested), there has been considerable debate over what exactly qualifies as bullshit. Most of that debate centers on the question of intention. Is bullshit considered bullshit if the deception was unintentionally presented? West and Bergstrom think that it is. They write, “Whether or not that usage is appropriate, we feel that the verb phrase calling bullshit definitely applies to falsehoods irrespective of the intentions of the author or speaker.”

The reason for the class’s existence comes down to a simple and somewhat alarming reality: even the most educated and savvy consumer of information is easily misled in today’s complex information ecosystem. Calling Bullshit is not dedicated to teaching students that Fox News promotes “fake news” or that National Enquirer headlines are fallacious. Instead, the class operates under the assumption that the structures through which today’s endless information comes to the consumer – algorithms, data graphics, info analytics, peer-reviewed publications – are in many ways as full of bullshit as the fake news we easily recognize as bogus. One scientist that West and Bergstrom cite in their syllabus goes so far as to say that, due to the fact that journals are prone to only publish positive results, “most published scientific results are probably false”.

Why smart people are more likely to believe fake news

A case in point is a 2016 article called Automated Inferences on Criminality Using Face Images. In it, the authors present an algorithm that can supposedly teach a machine to determine criminality with 90% accuracy based solely on a person’s headshot. Their core assumption is that, unlike humans, a machine is relatively free of emotion and bias. West and Bergstrom call bullshit, sending students to explore the sample of photos used to represent criminals in the experiment: all them are of convictedcriminals. The professors claim that “it seems less plausible to us that facial features are associated with criminal tendencies than it is that they are correlated with juries’ decisions to convict”. Conclusion: the algorithm is more correlated with facial characteristics that make a person convictable than a set of criminal inclinations.

By teaching ways to find misinformation in the venues many of us consider pristine realms of expertise – peer-reviewed journals such as Nature, reports by the National Institutes of Health, TED Talks – West and Bergstrom highlight the ultimate paradox of the information age: more and more knowledge is making us less and less reasonable.

‘Even the most educated and savvy consumer of information is easily misled in today’s complex information ecosystem.’ Photograph: Ritchie B Tongo/EPA

As we gather more data for mathematical models to better analyze, for example, the shrinking gap between elite male and female runners, we remain as prone as ever to misusing that data to achieve erroneous results. West and Bergstrom cite a 2004 Nature article in which the authors use linear regression to trace the closing gap between men and women’s running times, concluding that women will outpace men in the year 2156. To take down this kind of bullshit, the professors introduce the idea of reductio ad absurdum, which in this case would make the year 2636 far more interesting than 2156, as it’s then that, if the Nature study is right, “times of less than zero will be recorded”.

West and Bergstrom first offered the class in January of 2017 with modest expectations. “We would have been happy if a couple of our colleagues and friends would have said: ‘Cool idea, we should pass that along,’” West says. But within months the course had made national – and then international – news. “We have never guessed that it would get this kind of a response.”

To say that a nerve has been touched would be an understatement. After posting their website online, West and Bergstrom were swamped with emails and media requests from all over the world. Glowing press reports of the class’s ambitions contributed to the growing sense that something seismic in higher education was under way.

The professors were especially pleased by the interest shown among other universities – and even high schools – in modeling a course after their syllabus. Soon the Knight Foundation provided $50,000 for West and Bergstrom to help high school kids, librarians, journalists, and the general public become competent bullshit detectors.

In 1945, when Harvard University defined for the nation the role of higher education with its report on General Education in a Free Society, it stressed as its main goal “the continuance of the liberal and humane tradition”. The assumption, which now seems quaint, was that knowledge, which came from information, was the basis of character development.

Calling Bullshit, which provides the tools for every American (the lectures and readings are all online) to disrupt the foundation of even the most trusted source of information, reveals how profoundly difficult endless information has made the task of achieving that humane tradition. How the necessary shift from conveying wisdom to debunking it will play out is anyone’s guess, but if West and Bergstrom get their way – and it seems that they are – it will mean calling a lot of bullshit before we get to the business of becoming better citizens.

Friday, 20 July 2018

Pakistan's Trials

Let’s face it. Whatever some may think of Nawaz Sharif’s omissions and however much others may hate him for his commissions, the fact remains that he has demonstrated the courage of his conviction that the unaccountable Miltablishment has no business interfering in the affairs of an elected government, much less in engineering its rise or fall.

Nawaz has held firm to this conviction since 1993 when he was dismissed from office, restored by the Supreme Court and then compelled to step aside. He met the same fate in 1999 and spent seven years in forced exile. Now he is behind the bars for the same “crime” (he insisted on putting General Pervez Musharraf on trial for treason and demanding an end to the politics of non-state actors in domestic and foreign policy). He could have spent another ten years in exile in the comfort of his luxury flats in London – much like Benazir Bhutto, General Musharraf or Altaf Hussain, closer to home, and Lenin, Khomeini and many others in historical time — and looked after his ailing wife. But he chose instead to return, along with his daughter, and go straight to jail “to honour the sanctity of the ballet box”.

This is an unprecedented political act with far reaching consequences. It has driven a spike in the Punjabi heartland of the Miltablishment and irrevocably degraded the ultimate source of its power and legitimacy. The provinces of Balochistan, Sindh and KP have witnessed outbursts of anti-”Punjabi Miltablishment” sub-nationalism from time to time but this is the first time in 70 years that a sizeable chunk of Punjab is simmering not against the “subversive” parties and leaders of other provinces but against its very own “patriotic” sons of the soil. This is that process whereby the social contract of overly centralized and undemocratic states is rent asunder. In that sense, it is the Miltablishment which is on trial.

Unfortunately, the judiciary, too, is on trial. In a democratic dispensation, it is expected to fulfil three core conditions of existence. First, to provide justice to lay citizens in everyday matters. Second, to uphold the supremacy of parliament. Third, to remain above the political fray as a supremely neutral arbiter between contending parties and institutions. On each count, tragically, it seems amiss. Hundreds of thousands of civil petitioners have been awaiting “insaf” for decades. The apex courts are making laws instead of simply interpreting them. And the mainstream parties and leaders are at the receiving end of the stick while “ladla” sons and militants are getting away with impunity. At some time or the other in the past or present, controversy has dogged one or more judges. But the institution of the judiciary is in the dock of the people today because it is perceived as aiding and abetting the erosion of justice, neutrality and vote-sanctity. In 2007, the “judicial movement for independence” erupted against an arbitrary act by a dictator against a judge. In that historical movement, the PMLN was fully behind the lawyers and judges. The irony in 2018, however, is that the same lawyers and judges are standing on the side of authoritarian forces against the PMLN.

The third “pillar” of the state – Media – is no less on trial. It is expected to “freely” inform the people so that they can make fair and unbiased choices. But it is doing exactly the opposite. A couple of media houses have succumbed to severe arm-twisting and opted to gag themselves; many have meekly submitted to censorship “advice”; most are silent for or blind for material gains. The proliferation of TV channels was meant to be a bulwark against authoritarian or unaccountable forces. But a failing economy and political uncertainty has pitted the channels against one other for the crumbs, which has given a leg up to those on the “right side” of the fence. At any rate, the corporatization of the media by big capitalist interests has served to protect the powerful at the expense of the weak.

Finally, the fourth pillar of the state — Parliament — is about to be stripped of its representative credentials. The castration of the two mainstream parties and their leaders is aimed at empowering one “ladla” leader and his party, a host of militant religious groups and a clutch of opportunist “independents” to storm the citadels of the legislature.

Is all hope lost? Are we collectively fated to be victims of a creeping authoritarian and unaccountable coup by the “pillars” of the state in tandem?

No. Sooner than later, the media and judiciary will begin to crack. Neither can survive by being “pro-government” for long. Every chief justice seeks to make his own mark on history as distinct from his predecessor and no judge can shrug away the weight of popular opinion for long. The electronic and print media, too, cannot allow social media to run away with independent digital news and analysis pegged to financial sources outside Pakistan.

Meanwhile, we, the people, must get ready to suffer.

Tuesday, 5 June 2018

The Marwari hegemony of Indian Media

A FRESH Cobrapost sting operation has shown a number of big media outfits accepting money to spread fake news and whip up religious hysteria to boost the BJP’s chances in the 2019 elections. The Cobrapost is held in high regard and its exposés in the past have helped the interests of Indian democracy. This one, however, has left one a bit confused. Did we need to bribe Goebbels to do what he was already good at doing and was likely to do anyway?

Another way of seeing the matter is through the ideological affinity and collusion that exists between most media houses and Hindutva, which makes them predisposed ideologically to align with the BJP. Congress has elements the coterie can support, mainly with regard to business leeway. Otherwise, Indira Gandhi’s nationalisation of the banks, which they owned, and her initial flirtation with the left in a Nehruvian romance won her the clique’s disapproval. Even Rajiv Gandhi went for their jugular when he exhorted Congress workers to shake the moneybags off their backs. The business clique’s preference for a non-Gandhi Congress leader makes eminent sense.

A straight reading of Akshaya Mukul’s well-documented book Gita Press and the Making of Hindu India, for example, would nudge the reader to see the Cobrapost’s media sting — available on its website — from a different perspective. A key question flows from the operation. Would the media barons not work for the BJP or, worse, work against it, if they were not offered huge sums? One is not excluding the mercenary angle in the projection of a political idea and there are good arguments to see Hindutva as a business investment too, but more of that another time.

Mukul’s book is about India’s business community of Marwaris — who happen to own much, possibly most of the so-called mainstream newspapers and TV channels — and the coming about of the Gita Press in Gorakhpur. The right-wing press was to become the fountainhead of reactionary Hindu political and communal discourse and also a platform for mobilisation 1926 onwards against India’s Dalits, assorted minorities, but chiefly targeting the Muslims. The book also prompts an unintended question as an aside. Why is it that nearly all the exposés involving Marwari business houses are carried out in the form of books?

The answer lies in another question. Who owns the press? Consider the fact that William Caxton’s induction of the printing press in England in the 15th century was put to use in subsequent eras by capitalists, communists and evangelists alike. It served the purposes of colonialism via Macaulay and it also fashioned a mode of anti-colonial upsurge. Muslim and Hindu communalists harnessed the technology to vend their own venomous messages.

Interestingly, the first challenge to the Marwari hold on news dissemination came from a leftist public-minded intellectual, one Debjyoti Burman, in 1950 in the form of a book. He wrote the Mystery of the Birla House as an exposé on the Calcutta-based business group. But the Birlas reportedly bought all three editions and eventually the copyrights of the book.

Mr Burman, however, presented his book to Purushottam Das Tandon, president of the Nasik session of Congress. In the foreword, he expressed the hope that Mr Tandon “will hear the tears falling and throw his weight on the side of the masses to save the country from ruthless exploitation”.

Burman told Tandon that “the health, wealth and happiness of our people are being butchered” by the business group. A copy of the disappeared vignette exists in the ‘rare textbooks’ section of the Nehru Memorial Library in Delhi. Other books on Marwari business houses have been made to disappear mysteriously. In fact, in his quest for material on the Gita Press, Mukul found that copies of a rival journal that wrote detailed profiles of Indian communities were available for most groups but not the one that covered the Marwaris. He retrieved it anyhow with the help of a private archivist.

While the books that have either disappeared or failed to find vendors dealt mostly with financial exposés and the dark backstage of businesses, Mukul’s work deals with the Marwari pursuit of a religious and cultural platform to propagate their worldview, which invariably waded into politics, usually of a scurrilous kind.

“I wanted one of the issues of the journal Chand, which used to come out in the early 1920s — a particular issue on Marwaris, which was banned in that period,” Mukul has been quoted as saying in an interview. “Chand was taking on all castes. It brought out issues on Kayasths too so it was an equal opportunity offender. They did it to everyone; they were quite a gang. I was looking for this ‘Marwari Ank’ but all the libraries in Allahabad and Banaras had all the issues of Chand but not that one because it was banned at that time and the community had bought up all the issues and destroyed them. But one antiquarian in Banaras dug up this copy of ‘Marwari Ank’ for me! So there are people who helped a lot outside the archives.”

There was a time when Marwari-owned newspapers ran professional outfits with editors valued for their integrity. That seems to have been more of an enforced discipline to conform to the political climate of secularism firmly tethered to a mixed economy driven by socially driven five-year plans.

The Cobrapost’s revelations are important to palpably feel the extent of the rot in the Indian media. But any suggestion that the newspapers and TV channels owned by the Gita Press-minded businesses were driven by the profit motive alone is to stretch the point.

“The idea [behind the Marwari publication] was that Hinduism should speak in one voice just like Islam does,” says Mukul. “According to them, Hindus were in big trouble because they didn’t speak in one voice.”