“Blessed is the nation that doesn’t need heroes" Goethe. “Hero-worship is strongest where there is least regard for human freedom.” Herbert Spencer

Search This Blog

Saturday 6 February 2021

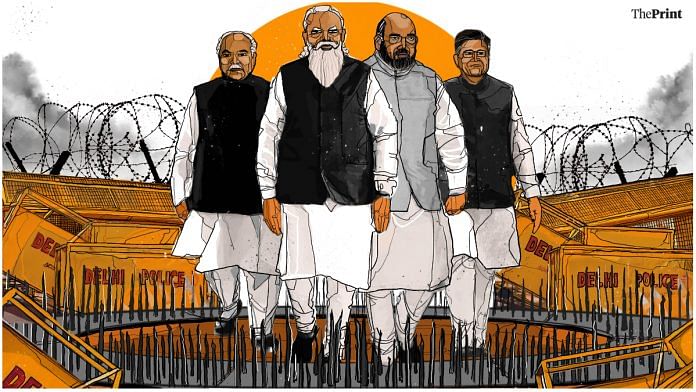

Modi govt has lost farm laws battle, now raising Sikh separatist bogey will be a grave error

Protests over the three farm reform laws are well into the third month now. There are six key facts, or facts as we see them, that we can list here:

1. The farm laws, by and large, are good for the farmers and India. At various points of time, most major political parties and leaders have wanted these changes. However, many of you might still disagree. But then, this is an opinion piece. I explained it in detail in this, Episode 571 of #CutTheClutter.

2. Whether the laws are good or bad for the farmer no longer matters. In a democracy, all that matters is what people affected by a policy change believe — in this case, the farmers of the northern states. Facts don’t matter if you’ve failed to convince them.

3. The Modi government is right when it says this is no longer about the farm laws. Because nobody is talking about MSP, subsidies, mandis and so on. Then what’s it about?

4. The short answer is, it is about politics. And why not? There is no democracy without politics. When the UPA was in power, the BJP opposed all its good ideas, from the India-US nuclear deal to FDI in insurance and pension. Now it’s implementing the same policies at the rate of, say, 6X.

5. As far as the farm laws are concerned, the Modi government has already lost the battle. Again, you can disagree. But this is my opinion. And I will make my case.

6. Finally, the Modi government has two choices. It can let it fester, expand into a larger political war. Or it can cut its losses and, as the Americans say, get off the kerb.

Here is the evidence that lets us say that the Modi government has lost the battle for these farm laws.

You see even a Modi-Shah BJP is unlikely to risk reopening this front at that point. In fact, the bellwether heartland state elections, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan, will be exactly 12 months away. Two of them have strong Congress incumbents and in the third, the BJP has bought and stolen power. Nobody’s risking losing these to make their point over farm reforms. These laws, then, are as bad as dead in the water.

Again, unilaterally, the government has already made a commitment of continuing with Minimum Support Price (MSP), although there is nothing in the laws saying it will be taken away. With so much already given away, the battle over the farm laws is lost.

The Modi government’s challenge now is to buy normalcy without making it look like a defeat. We know that it got away with one such, with the new land acquisition law. But that issue was still confined to Parliament. This is on the streets, highway choke-points, and in the expanse of wheat and paddy all around Delhi. This can spread. If the government retreats in surrender, this issue may close, but politics will rage. And why not? What is democracy but competitive politics, brutal, fair and fun? The next targets will then be other reform measures, from the new labour laws to the public listing of LIC.

What are the errors, or blunders, that brought India’s most powerful government in 35 years here? I shall list five:

1. Bringing in these laws through the ordinance route was a blunder. I speak from 20/20 hindsight, but then I am a commentator, not a political leader. To usher in the promise of sweeping change affecting the lives of more than half a billion people, the correct way would have been to market the ideas first. We don’t know if Narendra Modi now regrets not having prepared the ground for it. But the fact is, people at the mass level would be suspicious of such change through ordinances. Especially if you aren’t talking to them.

2. The manner in which the laws were pushed through Rajya Sabha added to these suspicions. This needed better parliamentary craft than the blunt use of vocal chords. This helped fan the fire, or spread the ‘hawa’ that something terrible was being forced down the surplus-producing farmers’ throats.

3. The party was riding far too high on its majority to care about allies and friends. If it had taken them along respectfully, the passage through Rajya Sabha wouldn’t have been so ungainly. At least the Akalis should never have been lost. But, as we’ve said before, this BJP does not understand Punjab or the Sikhs.

4. It also underestimated the frustration among the Jats of Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh, disempowered by the Modi-Shah politics. The senior-most Jat leaders in the Modi council of ministers are both inconsequential ministers of state. One is from distant Barmer in Rajasthan. The most visible of them, Sanjeev Balyan, won from Muzaffarnagar, where the big pro-Tikait mahapanchayat was held. In Haryana, the BJP has no Jat who counts. On the contrary, it found the marginalisation of Jat power as its big achievement. It refused to learn even from statewide, violent Jat agitations for reservations. The anger then was rooted in political marginalisation, as it is now. Ask why the BJP’s Jat ally Dushyant Chautala, or any of its Jat MPs/MLAs in UP, especially Balyan, are not on the ground, marketing these reforms? They wouldn’t dare.

5. The BJP conceded too much, too soon, unilaterally in the negotiations. It doesn’t have much more to give now. And the farm leaders have conceded nothing.

In conclusion, where does the Modi government go from here? One approach could be to tire the farmers out. On all evidence, that is not about to happen. Rabi harvest in April is still nearly 75 days away, and with much work done by mechanical harvesters and migrant workers, families would be quite capable of keeping the pickets full.

The next expectation would be that the Jats would ultimately make a deal. This is plausible. Note the key difference between Singhu and Ghazipur. In the first, no politician can even go for a selfie. Ask Ravneet Singh Bittu of the Congress, who was turned out unceremoniously. But everybody can go to Ghazipur and be photographed hugging Tikait. The Congress, Left, RLD, RJD, AAP, all of them. Even Sukhbir Singh Badal comes to Ghazipur, instead of Singhu to meet his fellow Sikhs from Punjab. Wherever there is politics and politicians, conflict resolution is possible. But what happens if this becomes a reality?

This will leave India and the Modi government with the most dangerous outcome of all. It will corner the Sikhs of Punjab. Already, the lousy barricading visuals and government’s prickly response to something as trivial as some celebrity tweets is threatening to redefine the issue from farm laws to national unity. The Modi government will err gravely if it changes the headline from farm protests to Sikh separatism.

This crisis requires political sophistication and governance skills. This BJP has neither. It has, instead, political skills and governance by clout, riding an all-conquering election-winning machine. It is the party’s inability to accept the realities of Indian politics and appreciate the limitations of a parliamentary majority that brought it here.

Does it have the smarts and sagacity to negotiate its way out of it? We can’t say. But we hope it does. Because the last thing India needs is to start another war for national unity. You would be nuts to reopen an issue in Punjab we all closed and buried by 1993.

Wednesday 3 February 2021

Saturday 30 January 2021

Friday 29 January 2021

Thursday 28 January 2021

Wednesday 27 January 2021

Sunday 24 January 2021

On the Indian Farmers' Agitation for MSP

By Girish Menon

In this article I will try to explain the logic behind the Delhi protests by farmers demanding a Minimum Support Price (MSP).

If you are a businessman who has produced say 1000 units of a good; and are able to sell only 10 units at the price that you desired. Then it means you will have an unsold stock of 990 units. You now have a choice:

Either keep them in storage and sell it to folks who may come in the future and pay your asking price.

Or get rid of your unsold stock at whatever price the haggling buyers are willing to pay.

If you decide on the storage option then it follows that your goods are not perishable, it’s value does not diminish with age, you have adequate storage facilities and you have the resources to continue living even when most of your goods are unsold.

If you decide on the distress sale option it could mean that your goods are perishable and/or it’s value diminishes with age and/or you don’t have storage facilities and/or you are desperate to unload your stuff because for you whatever money you get today is important for your survival,

If one were to approach any small farmers’ output, I think such a farmer does not have the storage option available to him. Hence, he will have to sell his output to the intermediary at any price offered. This could mean a low price which results in a loss or a high price resulting in a profit to the farmer.

Whether the price is high or low depends on the volume of output produced by all farmers of the same output. And, no farmer is able to predict the likely future harvest price he would get at the moment he decides what crop to grow.

Thus a subsistence farmer, without storage facilities, is betting on the future price he could get at harvest time. This is a bet that destroys subsistence farmers from time to time when market prices turn really low due to a bumper harvest.

Subjecting subsistence farmers to ‘market forces’ means that some farmers will get bankrupted and be forced to leave their village and go to the city in search of a means of living. In many developed countries, governments have tried to prevent farmer exodus from villages by intervening and ensuring that farmers receive a decent return for their toils,

MSP is a government guarantee of a minimum price that protects farmers who cannot get their desired price at the market, The original draft of the farm law bills passed by the Indian Parliament has no mention of MSP. Also, in Punjab etc., some of these agitating farmers are already being supported with MSP by the state government and they fear that the new bills will take away their protection.

This is a simple explanation of the demand for MSP.

It must also be remembered that:

Unlike the subsistence farmer, the middleman who buys the farmers’ output is usually a part of a powerful cartel and who enjoys more market power than the farmer.

As depicted in ‘Peepli Live’ destitute farmers, if forced to leave their villages, will add to supply of cheap labour in an era of already high unemployment.

These destitute may squat on a city’s scarce public spaces and be an ‘eyesore’ to the better off city dwellers.

Some farmers may even contemplate suicide and this will produce less than desirable PR optics for any 'caring' government.

Tuesday 12 January 2021

Saturday 26 December 2020

Saturday 5 December 2020

Thatcher or Anna moment? Why Modi’s choice on farmers’ protest will shape future politics

Has the farmers’ blockade of Delhi brought Narendra Modi to his Thatcher moment or Anna moment? It is up to Modi to answer that question as India waits. It will write the course of India’s political economy, even electoral politics, in years to come.

For clarity, a Thatcher moment would mean when a big, audacious and risky push for reform, that threatens established structures and entrenched vested interests, brings an avalanche of opposition. That is what Margaret Thatcher faced with her radical shift to the economic Right. She locked horns with it, won, and became the Iron Lady. If she had given in under pressure, she’d just be a forgettable footnote in world history.

--Also watch

Anna moment is easier to understand. It is more recent. It was also located in Delhi. Unlike Thatcher who fought and crushed the unions and the British Left, Manmohan Singh and his UPA gave in to Anna Hazare, holding a special Parliament session, going down to him on their knees, implicitly owning up to all big corruption charges. Singh ceded all moral authority and political capital.

By the time Anna returned victorious for the usual rest & recreation at the Jindal fat farm in Bangalore, the Manmohan Singh government’s goose had been cooked. Anna was victorious not because he got the Lokpal Bill. Because that isn’t what he and his ‘managers’ were after. Their mission was to destroy UPA-2. They succeeded. Of course, helped along by the spinelessness as well as guilelessness of the UPA.

Modi and his counsels would do well to look at both instances with contrasting outcomes as they confront the biggest challenge in their six-and-a-half years. Don’t compare it with the anti-CAA movement. That suited the BJP politically by deepening polarisation; this one does the opposite. It’s a cruel thing to say, but you can’t politically make “Muslims” out of the Sikhs.

That “Khalistani hand” nonsense was tried, and it bombed. It was as much of a misstep as leaders of the Congress calling Anna Hazare “steeped in corruption, head to toe”. Remember that principle in marketing — nothing fails more spectacularly than an obvious lie. As this Khalistan slur was.

The anti-CAA movement involved Muslims and some Leftist intellectual groups. You could easily isolate and even physically crush them. We are merely stating a political reality. The Modi government did not even see the need to invite them for talks. With the farmers, the response has been different.

Besides, this crisis has come on top of multiple others that are defying resolution. The Chinese are not about to end their dharna in Ladakh, the virus is raging and the economy, downhill for six quarters, has been in a free fall lately. Because politically, economically, strategically and morally the space is now so limited, this becomes the Modi government’s biggest challenge.

Also read: Shambles over farmers’ protest shows Modi-Shah BJP needs a Punjab tutorial

Modi has a complaint that he is given too little credit as an economic reformer. That he has brought in the bankruptcy law, GST, PSU bank consolidation, FDI relaxations and so on, but still too many people, especially the most respected economists, do not see him as a reformer.

There is no denying that he has done some political heavy lifting with these reformist steps. But some, especially GST, have lost their way because of poor groundwork and execution. And certainly, all that the sudden demonetisation did was to break the economy’s momentum. His legacy, so far, is of slowing down and then reversing India’s growth.

Having inherited an economy where 8 per cent growth was the new normal, now RBI says it will be 8 per cent, but in the negative. It isn’t the record anybody wanted in his seventh year, with India’s per capita GDP set to fall below Bangladesh’s, according to an October IMF estimate.

The pandemic brought Modi the “don’t waste a crisis” opportunity. If Narasimha Rao and Manmohan Singh with a minority government could use the economic crisis of 1991 to carve out a good place for themselves in India’s economic history, why couldn’t he now? That is how a bunch of audacious moves were announced in a kind of pandemic package. The farm reform laws are among the most spectacular of these. Followed by labour laws.

This is comparable now to the change Margaret Thatcher had dared to bring. She wasn’t dealing with multiple other crises like Modi now, but then she also did not have the kind of almost total sway that Modi has over national politics. Any big change causes fear and protests. But this is at a scale that concerns 60 per cent of our population, connected with farming in different ways. That he and his government could have done a better job of selling it to the farmers is a fact, but that is in the past.

The Anna movement has greater parallels, physically and visually, with the current situation. Like India Against Corruption, the farmers’ protest also positions itself in the non-political space, denying its platform to any politician. Leading lights of popular culture are speaking and singing for it. Again, there is widespread popular sympathy as farmers are seen as virtuous, and victims. Just like the activists. Its supporters are using social media just as brilliantly as Anna’s.

Also read: How protesting farmers have kept politicians out of their agitation for over 2 months

There are some differences too. Unlike UPA-2, this prime minister is his own master. He doesn’t need to defer to someone in another Lutyens’ bungalow. He has personal popularity enormously higher than Manmohan Singh’s, great facility with words and a record of consistently winning elections for his party.

But this farmers’ stir looks ugly for him. His politics is built so centrally on the pillar of “messaging” that pictures of salt-of-the-earth farmers with weather-beaten faces, cooking and sharing ‘langars’, offering these to all comers, then refusing government hospitality at the talks and eating their own food brought from the gurdwara while sitting on the floor, and the widespread derision of the “Khalistani” charge is just the kind of messaging he doesn’t want. In his and his party’s scheme of things, the message is the politics.

Thatcher had no such issues, and Manmohan Singh had no chips to play with. How does Modi deal with this now? The temptation to retreat will be great. You can defer, withdraw the bills, send them to the select committee, embrace the farmers and buy time. It isn’t as if the Modi-Shah BJP doesn’t know how to retreat. It did so on the equally bold land acquisition bill, reeling under the ‘suit-boot ki sarkar’ punch. So, what about another ‘tactical retreat’?

It will be a disaster, and worse than Manmohan Singh’s to the Anna movement. At the heart of Modi’s political brand proposition is a ‘strong’ government. It was early days when he retreated on the land acquisition bill. The lack of a Rajya Sabha majority was an alibi. Another retreat now will shatter that ‘strongman’ image. The opposition will finally see him as fallible.

At the same time, farmers blockading the capital makes for really bad pictures. These aren’t nutcases of ‘Occupy Wall Street’. Farmers are at the heart of India. Plus, they have the time. Anybody with elementary familiarity with farming knows that once wheat and mustard, which is most of the rabi crop in the north, is planted, there isn’t that much to do until early April.

You can’t evict them as in the many Shaheen Baghs, and you can’t let them hang on. Even a part surrender will finish your authority. Because then protesters against labour reform will block the capital. That’s why how Modi answers this Thatcher or Anna moment question will determine national politics going ahead. Our wish, of course, is that he will choose Thatcher over Anna. It will be a tragedy if even Modi were to lose his nerve over his boldest reforms.

Friday 22 November 2019

Sunday 20 May 2018

Wednesday 20 April 2016

Only a dream can end a nightmare

INDIA may be waking up from its unwarranted nightmare. A call has gone out from the head of its most impoverished and second-most populous province to cobble an anti-Hindutva alliance to foil a fascist takeover. The conditions look ripe. The economy is not shining.

There are many explanations. One is the piranha-like tycoons spawned by a neo-liberal ruling clique. In the rest of the world, neo-liberalism is being questioned. Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn have lent voice to a global movement in India too. When university campuses reverberated with socialist slogans recently, the government moved swiftly to muzzle them. It contrived and slapped sedition charges on some of the most inspiring student leaders the country has seen.

Another explanation for the economic mess lies in straightforward loot. The mercantile capitalists embraced by Gandhi as the ‘trustees’ of free India have literally walked away with mega tons of people’s money. They have shown the banks a clean pair of heels. The Supreme Court is furious and wants names named. The national security adviser has stepped in with a more riveting agenda. He wants the courts to focus on national security instead; in other words to hang and jail more people, more swiftly.

To compound the nation’s woes, drought has arrived and monsoons are not due for at least two more scorching months. Much of the suffering this entails is predictably man-made. Millions are being kept parched so that the water tanker mafia, among other connected crony entrepreneurs, prospers.

Jack Nicholson as a sleuth investigated the great water heist in the formative days of California. That was in Polanski’s Chinatown when the snoopy hero nearly got his nose fed to the villain’s goldfish. A few good Indian journalists, led by Sreenivasan Jain and P. Sainath, are showing the red flag from parched swathes. Himanshu Thakkar, India’s respected expert on water management, is warning against its plunder in the heart of drought land, on lush golf courses.

The revered cow, essence of India’s refurbished nationhood, is in trouble. Many will perish by hunger, others by choking on plastic bags they scrounge in the absence of fodder. (The incidence of pedigree dogs being abandoned has increased, an indication that the urban middle class is feeling the pinch.)

An inordinately high number of farmers may be unable to stand up to the grim prospects. Some have committed suicide. Many more look just as vulnerable and could face starvation. The water minister says there is neither any need nor a way to prepare for a drought. A farmer’s two kindergarten children were on TV, sent off to Mumbai to find work and food.

Meanwhile, more illicit money has been found abroad. The Panama Papers could be only the tip of the iceberg. A two-year-old promise by the prime minister that he would put Indian Rs1.5 million from a separate tranche of retrieved money in everyone’s account has lapsed. His alter ego and party chief has described the promise as poll-year comment, not to be taken literally.

People are cursing their luck. The government is cursing the people. A faulty flyover being constructed in Kolkata has collapsed. The prime minister, in his election outfit, called it God’s curse on the ruling party of West Bengal. Then there was another man-made tragedy, in a temple in Kerala this time. Did we see someone biting his reckless tongue?

Being clumsy with rural folk has usually incurred a cost. Indian history is littered with episodes of peasant revolts. Drought and exploitation were and are at the source. The Patidar Movement of capitalist farmers in Gujarat is spinning out of control. The Jats are another prosperous agrarian community. They were used cynically against Muslims in western Uttar Pradesh. The ploy worked and it catapulted Modi in the general election. Now, faced with broken populist promises (which probably were not meant to be taken literally) the Jats are bracing for a showdown.

Remember that the Sikh peasants rose against the mighty Mughal empire and have refused to be subdued till today. When the state under Indira Gandhi sent the army against them, Sikh peasant-soldiers deserted the military in large numbers. The Indian Express report on Monday told a similar story from Haryana. Jat “policemen deserted their posts, sided with protesters,” said the front page lead story. The number of police deserters belonging to the Jat community was in the hundreds, the newspaper said, quoting unnamed highly placed sources privy to an official report being prepared on the flare-up.

History repeats itself, and that’s not a hollow cliché. With food scarcity in 1832 in Maharashtra, which is also the venue of India’s worst drought today, food riots spread against the moneylenders many of whose ilk form the current ruling elite. As for drought, peasants have historically attacked grain traders for practising witchcraft whereby they could stop rain. All this is recorded history.

We therefore need to take very seriously what Bihar chief minister Nitish Kumar says for he is nothing if not a brilliant peasant leader. A day after becoming party chief last week, he demanded the “largest possible unity” against the BJP by bringing Congress, the Left and regional parties on one platform before the 2019 general elections.

There are crucial elections under way in four or five states. The BJP has little to no chance in West Bengal, Kerala or Tamil Nadu. If at all it makes headway it should be in Assam. But this could not be a reason for anyone to rest on his or her laurels. India is in ferment, and its people cannot afford to be caught napping yet again.

Tuesday 30 June 2015

Teaching the poor to behave

By shifting the burden of poverty alleviation from the state onto the poor themselves, behavioural economists are ignoring the structural causes of poverty. They are also erasing the behaviour of the owners of capital from the poverty debate

The World Bank’s World Development Report (WDR) 2014 was about ‘Risk and Opportunity’. The 2013 WDR is simply named ‘Jobs’. The 2012 WDR is titled ‘Gender Equality and Development’.

Other WDR themes in the recent past include ‘Agriculture for Development’ (2008), ‘Equity and Development’ (2006), and ‘Building Institutions for Markets’ (2002). They all have an overt economic dimension. Naturally — for it’s a bank, after all. But the World Bank’s 2015 WDR is titled ‘Mind, Society and Behaviour’. That’s right. Now, what would a bank — or, if you prefer, a multilateral development finance institution — want with mind, society and behaviour?

There is a two-word answer to this question: behavioural economics. In its 2015 WDR, the World Bank makes a strong pitch to governments for applying behavioural economics to development policy.

As the report notes in its opening chapter, “The analytical foundations of public policy have traditionally come from standard economic theory.” Standard economic theory assumes that individuals are rational economic agents acting in their best self-interest.

But in the real world, people often behave irrationally, and not always in their own best economic interest. For instance, they might splurge when they could save, or give excessive weight to the immediate present as opposed to the distant future.

Is poverty a mindset?

Behavioural economics uses insights from psychology, anthropology, sociology and the cognitive sciences to come up with more realistic models of how people think and make decisions. Where these decisions tend to be flawed from an economic point of view, governments can intervene with policies aimed at ‘nudging’ the targeted citizens towards the right decision.

All this seems fairly unobjectionable. However, things change when behavioural economists focus their attention exclusively on the behaviour of the poor. Till date, there is no evidence that monitoring and ‘nudging’ the behaviour of the world’s poor is a better route to alleviate poverty than, say, monitoring and ‘nudging’ the behaviour of the financial elite. Surely the latter cannot be deemed as altogether rational economic agents — not after the 2008 crisis?

The second assumption of behavioural economics — presented as a new ‘finding’ based on research, and regurgitated wholesale by the 2015 WDR — is that the poor are less intelligent than the rich. It is an obnoxious idea, and also politically incorrect. Of course, this is not stated in as many words.

The correct way to say it, then, is to state that “the context of poverty” depletes a person’s “bandwidth” — the mental resources necessary to think properly — as a result of which he or she is, well, a poor decision-maker, especially compared to those who are not in “the context of poverty”, such as the rich and the middle classes.

Lest anyone misunderstand, the authors of the report hasten to add that it’s not just the poor but anyone — even the wealthy — who, when placed in a “context” of poverty, would make wrong decisions. (For the record, it must be noted that the poor are — all else being equal — more likely to be in “the context of poverty” than the rich.)

To support these assumptions, a number of research studies are trotted out. One such study, mentioned in the report, was conducted on Indian sugarcane farmers, who typically receive their income once a year, at the time of harvest.

It was found that the farmers’ IQ was ten points lower before they received their harvest income than afterward (when they were flush with cash and were comparatively richer). So ideally, they should not take major financial decisions before harvest time. Such an insight into how poverty affects behaviour could have policy implications for, say, cash transfers — which can be timed, or made conditional, on displaying certain behaviours pre-determined by the state as ‘rational’.

The report states in all earnestness that poverty “shapes mindsets”. From here, it is a hop, skip, and jump to holding, as the leading behavioural economists of the day do, that the poor are poor because their poverty prevents them from thinking and acting in ways that can take them out of poverty.

Thus the focus as well as the burden/responsibility of poverty-alleviation would shift from the state — from macroeconomic policy, from having to provide employment, health and education — to changing the behaviour of the poor. The structural causes of poverty — rising inequality and unemployment — as well as the behaviour of the owners of capital are evicted from the poverty debate, and no longer need be the focus of public policy.

Behavioural economics

In this context, it might be pertinent to note that the rise of behavioural economics as a discipline parallels the rise of neoliberalism, starting from the 1980s and rapidly gaining respectability and funding from the 1990s. All the leading lights of the field such as Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, Robert Shiller, Senthil Mullainathan, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein made their mark in this period, and are heavily referenced in this report.

A fundamental principle of neoliberal thought is to find market-led solutions to socio-economic problems. No matter that poverty is often a symptom of market failure. Free market ideologues attribute poverty and all socio-economic ills to market distortions caused by state interference. The economists who get to shape the World Bank’s WDRs are chosen for their ability to toe this line.

On the odd occasion that the lead author of a WDR made a bid for intellectual independence, he had to make an untimely exit. For the 2000-01 WDR, titled ‘Attacking Poverty’, the original draft prepared by the distinguished development economist Ravi Kanbur — incidentally brought in by Joseph Stiglitz — spoke of the need to build effective safety nets for the poor before the introduction of free market reforms.

Both Mr. Kanbur and Mr. Stiglitz were out of the World Bank before the report was. As the economist Robert Wade points out in an essay on this episode, titled ‘Showdown at the World Bank’, the version eventually published no longer spoke of creating prior safety nets for the poor. It instead called for putting them in place “simultaneously with labour-shedding reforms”.

The point of this detour into WDR history is that — to borrow the jargon of behavioural economics — the overarching necessity to conform to free market ideology may be said to impose a ‘cognitive tax’ on World Bank economists, as a result of which their ‘mental models’ do not permit the ‘framing’ of poverty in ways that may contradict this ideology.

The Keynesian formula of safety nets from the free market may well be permanently banished from the policy agenda. But that still leaves unresolved the problem of how to manage the social and political consequences of the widening income gap between the 1 per cent and the 99 per cent. This is critical because growing discontent could lead to political instability. After all, in order for markets to function, and commodities to flow freely and predictably, the excluded masses must be taught to behave. This is where behavioural economics comes in.

Action and behaviour

In order to change the behaviour of the poor, one must first understand it. It is this understanding that behavioural economics promises to codify into knowledge. To be sure, the WDR readily acknowledges that even the rich, the economists, and the World Bank staff themselves, might be subject to cognitive biases.

But nowhere in its 230-odd pages does the report present an instance, or even a hypothetical example, of a behavioural economics-inspired policy intervention whose target is, say, a class of billionaire investors, despite the fact that today, compared to the poor, this is a group that wields far more influence, per capita, on a nation’s economic destiny. Changing their behaviour — for instance, manipulating them into deploying their billions on productive rather than speculative investments — could generate more beneficial, and more effective, outcomes than micro-manipulating the financial decisions of a poor peasant.

A major confusion that dogs this report is the conflation of ‘action’ and ‘behaviour’. The term ‘behaviour’ comes with the baggage of the empirical sciences. It is typically used with reference to animals and objects under scientific observation. Behaviours can be studied for patterns. To the extent that human beings are also animals, they can also be said to exhibit behaviours. But what makes them human is precisely their capacity to transcend behaviour patterns — in other words, to act.

The political theorist Hannah Arendt, in The Human Condition, speaks of three kinds of human activity: labour, work and action. Of the three, what distinguishes action is its political nature. When behaviourist economics speaks of poverty as a “cognitive tax”, it writes ‘action’ — the political agency of the poor — out of the equation.

As democratic nation states reorient themselves to being accountable to global financial markets, non-democratic bodies such as the World Trade Organization, and trade agreements such as General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and Trade in Services Agreement , they will necessarily become less responsive to the aspirations of their own citizens. With overt repression not always the most felicitous or cost-effective policy option, it has become imperative to find ways and means to ideologically tame the economically excluded. Hence the new focus on the minds and behaviour of the poor.

Behavioural economics, insofar as it is concerned with the behaviour of people in poverty — and it is this stream which dominates this year’s WDR — is simply the latest addition to the neo-liberal toolkit of political management.

Wednesday 29 February 2012

Warren Buffet - a Jaded Sage?

By Chan Akya in Asia Times Online

Warren Buffett, besides being the Sage of Omaha and one of the wealthiest men to ever walk this planet, is also an American hero. A man who popularized the notion of investing your savings prudently, taking a knife to Wall Street excesses and more recently, the architect of an effective minimum tax for rich Americans. All in all, your regular billionaire next door.

Of course I can also recount all the reasons why anyone who bothered to print this article and read the first paragraph got disgusted, crumpled the paper into a little ball and threw it into the nearest waste bin.

You know, stuff like his holdings in major American scams like Moody's which he purchased due to the massive profits they were making from selling fake triple-A ratings all around. Or his rescue of such amazing firms as Goldman Sachs in the midst of the financial crisis, in effect protecting them not so much from aggressive market speculators but perhaps the major regulatory bodies as well (Mr Buffett is a known supporter of and donor to President Barack Obama).

Even that supposed act of folksy good humor ("my secretary pays a higher tax rate than I do") hides an ugly word: "legacy". Mr Buffett is old and if he had wanted to pay higher taxes, well he had the last 60 years in which to do it.

But I don't care about any of Mr Buffett's flaws any more than I lose sleep over that stupid woman who unfailingly puts mayonnaise on my sandwich despite being told not to every day. My getting upset doesn't change a thing, and just ends up spoiling my day: it's easier for me to just buy my sandwiches somewhere else. That's where I left Mr Buffett - that is, until his latest investment letter hit the web and through acts of generosity by my friends, made it into my inbox. Ten times over.

Cold on gold

I don't know why so many of them did that - but it may have something to do with his statements about irrational choices that investor make about assets. He writes:

The major asset in this category is gold, currently a huge favorite of investors who fear almost all other assets, especially paper money (of whose value, as noted, they are right to be fearful). Gold, however, has two significant shortcomings, being neither of much use nor procreative. True, gold has some industrial and decorative utility, but the demand for these purposes is both limited and incapable of soaking up new production. Meanwhile, if you own one ounce of gold for an eternity, you will still own one ounce at its end.Okay, so if I understand this right, Mr Buffett objects to the fact that gold cannot be manipulated, conjured up out of thin air and that it draws a bunch of people weary of Keynesian money printing into its fold. I am not going to suggest that Mr Buffett is thick or something, but isn't all of the above the very point about owning a store of value in the first place?

What motivates most gold purchasers is their belief that the ranks of the fearful will grow. During the past decade that belief has proved correct. Beyond that, the rising price has on its own generated additional buying enthusiasm, attracting purchasers who see the rise as validating an investment thesis. As "bandwagon" investors join any party, they create their own truth - for a while.

I don't know about you, but if I could travel through the centuries I would sure as hell like to have in my pocket something that would still be worth something in purchasing power that approaches its current value.

Imagine the following scenario: your grandfather leaves us some wealth but you only get it 50 years later. Now, what would you have liked that "wealth" to have been: cash in US dollars or gold coins? Of course other assets would have worked better - "shares in Apple" for example. Then again, if your grandfather had given you shares in Apple and you got them in 1998, your general feelings of gratitude towards him would have been a somewhat dimmer.

Then Mr Buffett goes on with his diatribe:

Today the world's gold stock is about 170,000 metric tons. If all of this gold were melded together, it would form a cube of about 68 feet per side. (Picture it fitting comfortably within a baseball infield.) At $1,750 per ounce - gold's price as I write this - its value would be $9.6 trillion. Call this cube pile A. Let's now create a pile B costing an equal amount. For that, we could buy all US cropland (400 million acres with output of about $200 billion annually), plus 16 Exxon Mobils (the world's most profitable company, one earning more than $40 billion annually). After these purchases, we would have about $1 trillion left over for walking-around money (no sense feeling strapped after this buying binge). Can you imagine an investor with $9.6 trillion selecting pile A over pile B?Yup, valid points there. Then, again Mr Buffett, I wonder how those farmers would pay for the oil to use in their harvesters and how those oil workers would pay for all the grains they would need to eat. Would they own shares in each other and pay the other party dividends in kind? Or would they transact with a common currency, like gold?

... A century from now the 400 million acres of farmland will have produced staggering amounts of corn, wheat, cotton, and other crops - and will continue to produce that valuable bounty, whatever the currency may be. Exxon Mobil will probably have delivered trillions of dollars in dividends to its owners and will also hold assets worth many more trillions (and, remember, you get 16 Exxons). The 170,000 tons of gold will be unchanged in size and still incapable of producing anything. You can fondle the cube, but it will not respond.

And all the analysis misses the point about corporate fraud, that uniquely American preoccupation that has seen many a top firm go completely bust because of financial and accounting shenanigans. If Mr Buffett had mentioned BP instead of Exxon (and written this article two years ago rather than now) he would have had egg on his face. (See also "BP, Bhopal and Karma", Asia Times Online, June 19, 2010, one of my past articles on the subject of corporate responsibility.

Mr Buffett misses the point entirely about what gold is and what it is supposed to do. In a world where investors have ample reason to lose faith in governments and the financial system, the position of a common store of value that is recognizable and usable across all humanity and is itself beyond religion and politics in terms of being manipulated around (besides being no mean feat by itself) is made stronger, not weaker.

That is not to say that I am recommending you folks to buy gold and nothing else; my view has always been that a building up a little hedge for your financial assets with physical gold is no bad thing. I don't speculate in gold nor do I believe you should.

Of course, he clarifies similar points later on his spiel as follows:

My own preference - and you knew this was coming - is our third category: investment in productive assets, whether businesses, farms, or real estate. Ideally, these assets should have the ability in inflationary times to deliver output that will retain its purchasing-power value while requiring a minimum of new capital investment. Farms, real estate, and many businesses such as Coca-Cola, IBM and our own See's Candy meet that double-barreled test. Certain other companies - think of our regulated utilities, for example - fail it because inflation places heavy capital requirements on them. To earn more, their owners must invest more. Even so, these investments will remain superior to nonproductive or currency-based assets. Whether the currency a century from now is based on gold, seashells, shark teeth, or a piece of paper (as today), people will be willing to exchange a couple of minutes of their daily labor for a Coca-Cola or some See's peanut brittle. In the future the US population will move more goods, consume more food, and require more living space than it does now. People will forever exchange what they produce for what others produce.Really? The best that Mr Buffett can conjure up as stores of "productive" assets are those that generate software consulting services, sugared water with noxious chemicals and over-sweet artificially flavored foodstuffs? Is it possible that all of these companies will even exist 200 years from now, or will a bunch of lawsuits or corporate fraud take one or more of them down as they have many an American corporation?

This is neither about questioning his investment choices nor indeed to taunt a proud American on that country's potential failings. The investor letter though is emblematic of the core ill plaguing the West now; namely a failure to question the current logic of organization underpinning the economy.

On the other end of the scale, it is not immediately apparent that a deleveraging America would need as many cans of sugared water with noxious chemicals as it does now; nor indeed that the current system of savings through stocks could survive a Japan-style lost decade when the locus of the economy shifts from consumption to production.

In a different way of thinking, it is a good thing that Mr Buffett writes his letters the way he does now. Two decades from now, economists and students of finance may ponder the madness of our times that made a man like him the foremost investing genius in the world.

Sunday 18 December 2011

No Walmart, Please

The Tribune, India

Monday 5 December 2011

Big Farmer The poorest taxpayers are subsidising the richest people in Europe: and this spending will remain uncut until at least 2020.

What would you do with £245? Would you (a) use it to buy food for the next five weeks?, (b) put it towards a family holiday?, (c) use it to double your annual savings?, or (d) give it to the Duke of Westminster?

Let me make the case for option (d). This year he was plunged into relative poverty. Relative, that is, to the three parvenus who have displaced him from the top of the UK rich list(1). (Admittedly he’s not so badly off in absolute terms: the value of his properties rose last year, to £7bn). He’s the highest ranked of the British-born people on the list, and we surely have a patriotic duty to keep him there. And he’s a splendid example of British enterprise, being enterprising enough to have inherited his land and income from his father.

Well there must be a reason, mustn’t there? Why else would households be paying this money – equivalent to five weeks’ average spending on food and almost their average annual savings (£296)(2) – to some of the richest men and women in the UK? Why else would this 21st Century tithe, this back-to-front Robin Hood tax, be levied?

I’m talking about the payments we make to Big Farmer through the Common Agricultural Policy. They swallow €55bn (£47bn) a year, or 43% of the European budget(3). Despite the spending crisis raging through Europe, the policy remains intact. Worse, governments intend to sustain this level of spending throughout the next budget period, from 2014-2020(4).

Of all perverse public spending in the rich nations, farm subsidies must be among the most regressive. In the European Union you are paid according to the size of your lands: the greater the area, the more you get. Except in Spain, nowhere is the subsidy system more injust than in the United Kingdom. According to Kevin Cahill, author of Who Owns Britain, 69% of the land here is owned by 0.6% of the population(5). It is this group which takes the major pay-outs. The entire budget, according to the government’s database, is shared between just 16,000 people or businesses(6)*. Let me give you some examples, beginning with a few old friends.

As chairman of Northern Rock, Matt Ridley oversaw the first run on a British bank since 1878, and helped precipitate the economic crisis which has impoverished so many. This champion of free market economics and his family received £205,000 from the taxpayer last year for owning their appropriately-named Blagdon Estate(7). That falls a little shy of the public beneficence extended to Prince Bandar, the Saudi Arabian fixer at the centre of the Al-Yamamah corruption scandal. In 2007 the Guardian discovered that he had received a payment of up to £1bn from the weapons manufacturer BAE(8). He used his hard-earned wealth to buy the Glympton Estate in Oxfordshire(9). For this public service we pay him £270,000 a year(10). Much obliged to you guv’nor, I’m sure.

But it’s the true captains of British enterprise – the aristocrats and the utility companies, equally deserving of their good fortune – who really clean up. The Duke of Devonshire gets £390,000(11), the Duke of Buucleuch £405,000(12), the Earl of Plymouth £560,000(13), the Earl of Moray £770,000(14), the Duke of Westminster £820,000(15). The Vestey family takes £1.2m(16). You’ll be pleased to hear that the previous owner of their Thurlow estate, Edmund Vestey, who died in 2008, managed his tax affairs so efficiently that in one year his businesses paid just £10. Asked to comment on his contribution to the public good, he explained, “we’re all tax dodgers, aren’t we?”(17).

British households, who try so hard to keep the water companies in the style to which they’re accustomed, have been blessed with another means of supporting this deserving cause. Yorkshire water takes £290,000 in farm subsidies, Welsh Water £330,000, Severn Trent, £650,000, United Utilities, £1.3m. Serco, one of the largest recipients of another form of corporate welfare – the private finance initiative – gets a further £2m for owning farmland(18).

Among the top blaggers are some voluntary bodies. The RSPB gets £4.8m, the National Trust £8m, the various wildlife trusts a total of £8.5m(19). I don’t have a problem with these bodies receiving public money. I do have a problem with their receipt of public money through a channel as undemocratic and unaccountable as this. I have an even bigger problem with their use of money with these strings attached. For the past year, while researching my book about rewilding, I’ve been puzzling over why these bodies fetishise degraded farmland ecosystems and are so reluctant to allow their estates to revert to nature. Now it seems obvious. To receive these subsidies, you must farm the land(20).

As for the biggest beneficiary, it is shrouded in mystery. It’s a company based in France called Syral UK Ltd. Its website describes it as a producer of industrial starch, alcohol and proteins, but says nothing about owning or farming any land(21). Yet it receives £18.7m from the taxpayer. It has not yet answered my questions about how this has happened, but my guess is that the money might take the form of export subsidies: the kind of payments which have done so much to damage the livelihoods of poor farmers in the developing world.

In one respect the government of this country has got it right. It has lobbied the European Commission, so far unsuccessfully, for “a very substantial cut to the CAP budget”(22). But hold the enthusiasm. It has also demanded that the EC drop the only sensible proposal in the draft now being negotiated by member states: that there should be a limit to the amount that a landowner can receive(23). Our government warns that capping the payments “would impede consolidation” of landholdings(24). It seems that 0.6% of the population owning 69% of the land isn’t inequitable enough.

If subsidies have any remaining purpose it is surely to protect the smallest, most vulnerable farmers. The UK government’s proposals would ensure that the budget continues to be hogged by the biggest landlords. As for payments for protecting the environment, this looks to me like the option you’re left with when you refuse to regulate. The rest of us don’t get paid for not mugging old ladies. Why should farmers be paid for not trashing the biosphere? Why should they not be legally bound to protect it, as other businesses are?

In the midst of economic crisis, European governments intend to keep the ultra-rich in vintage port and racehorses at least until 2020. While inflicting the harshest of free market economics upon everyone else, they will oblige us to support a parasitic class of tax avoiders and hedgerow-grubbers, who engorge themselves on the benefactions of the poor.

www.monbiot.com

*UPDATE: It’s just dawned on me that the government’s list must be incomplete. It says it covers all “legal persons”, but it seems that legal persons excludes actual persons, as opposed to companies, partnerships, trusts etc. It would be fascinating to discover whose subsidies have not being listed.

References:

1. http://www.therichest.org/nation/sunday-times-rich-list-2011/

2. The average UK household contribution to the CAP is £245 (DEFRA, by email). Average household weekly expenditure on food and drink is £52.20. Average household weekly savings and investments is £5.70.

Office of National Statistics, 2010. Family Spending 2010 Edition. Table A1: Components of Household Expenditure 2009. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77-225698

3. DEFRA, by email.

4. European Commission, 19th October 2011. Regulation Establishing Rules for Direct Payments to Farmers Under Support Schemes Within the Framework of the Common Agricultural Policy. COM(2011) 625 final/2 2011/0280 (COD). http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/cap-post-2013/legal-proposals/com625/625_en.pdf

5. I wanted to go to source on this, but the copies available online are amazingly expensive (there’s an irony here, but I can’t quite put my finger on it). So I’ve relied on a report of the contents of his book: http://www.newstatesman.com/society/2010/10/land-tax-labour-britain

6. The database is here: http://www.cap-payments.defra.gov.uk/Download.aspx DEFRA’s database search facility isn’t working – http://www.cap-payments.defra.gov.uk/Search.aspx – so you’ll have to go through the spreadsheets yourself.

7. The entry in the database is for Blagdon Farming Ltd. I checked online: this is one of the properties of the Blagdon Estate. http://www.blagdonestate.co.uk/theblagdonhomefarm.htm , http://www.192.com/atoz/business/newcastle-upon-tyne-ne13/farming-mixed/blagdon-farming-ltd/292e5a6d3883fe2f4a207c94d6c41e61747a8b50/ml/ and http://www.misterwhat.co.uk/company/384132-blagdon-farming-ltd-newcastle-upon-tyne

8. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2007/jun/07/bae1

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2007/jun/09/bae.foreignpolicy

9. http://www.guardian.co.uk/baefiles/page/0,,2095831,00.html

10. The payment is listed as Glympton Farms Ltd. I rang them – they confirmed that Glympton Farms belongs to the estate.

11. Listed as Chatsworth Settlement Trustees. This page identifies the owners: http://www.boltonabbey.com/welcome_trustees.htm

12. Listed as Buccleuch Estates Ltd

13. Listed as Earl of Plymouth Estates Ltd.

14. Listed as Moray Estates Development Co.

15. Listed as Grosvenor Farms Limited. See http://www.grosvenorestate.com/Business/Grosvenor+Farms.htm

16. Listed as Thurlow Estate Farms Ltd. See http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1570710/Edmund-Vestey.html and http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/fat-cats-benefit-from-eu-farming-subsidies-780192.html

17. http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2008/dec/07/edmund-vestey-tax-will

18. All these utility companies are listed under their own names.

19. I stopped adding the wildlife trust payments shortly after getting down to the £100,000 level, so it is probably a little more than this.

20. The CAP’s Good Agricultural and Environmental Condition rules (an Orwellian term if ever there was one) forbid what they disparagingly call “land abandonment”.

21. http://www.tereos-syral.com/web/syral_web.nsf/Home/index.htm

22. DEFRA, January 2011. UK response to the Commission communication and consultation:

“The CAP towards 2020: Meeting the food, natural resources and territorial challenges of the future”. http://archive.defra.gov.uk/foodfarm/policy/capreform/documents/110128-uk-cap-response.pdf

23. European Commission, 19th October 2011, as above.

24. DEFRA, January 2011, as above.