Zoe Williams in The Guardian

Illustration by Jasper Rietman

What is a “middle-class” expense? According to the Daily Telegraph, after considerable dialogue with its own readers, the key items in the portfolio of the bourgeoisie are as follows: school fees, dental care, health insurance, holidays, wine (fine), new cars, holidays and “cultural activities”. The price rises in all these areas have been astronomical – health insurance has gone up by 51% over the past six years, school fees by 40% – while over the same period earnings in the double-average-wage bracket have gone down by 0.8%.

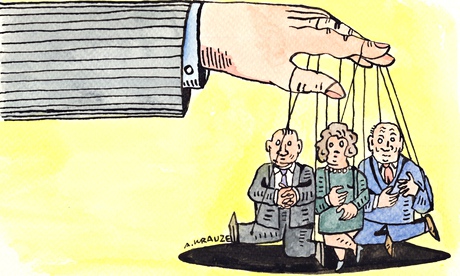

Private school fees are paid by 7% of the population; private health insurance is taken out by 11%. This isn’t really the middle: the determination to retain the term middle class for those who are actually wealthy is akin to the care with which the right wing never describes its views as rightwing, preferring “commonsense”. It is a constant project to reframe what is normal in the image of what is normal for one person in 10.

But actually, on this matter, the middle classes are pretty normal. Income has stagnated across every section of society apart from the top 1% (whom the Telegraph would probably call upper middle or well-to-do). GDP per capita is lower than it was seven years ago. “That,” said the economist Joseph Stiglitz in an interview on Sunday “is not a success.”

It’s hard for the wealthy to mobilise around their declining living standards. Their options are limited. When so much of your wealth is spent avoiding the social structures on which solidarity is based – education, the health service, our crap dentistry of international renown – who do you complain to? Who are you going to stand shoulder to shoulder with? Your outrage at the world is limited in its expression to your power as a consumer. That’s why the incredibly angry, bright pink man yelling at a BT helpline is such a staple of modern British sitcoms; as a guardian angel against feelings of impotence and injustice, BT can’t really help – even if it does answer the phone.

So there’s the stain of self-interest barring entry to the language and power and solace of unity. There’s also a huge amount of shame involved in being in debt or struggling, especially against the backdrop of assumption that privilege is somehow the result of a lifetime’s sound financial decisions.

There’s a public pressure not to mention declining living standards, because that would be to insult people whose living standards have declined to the point of being unable to eat. There’s also a private pressure, since the status of the affluent is, of course, rooted in the affluence – and if one breaks ranks to say there’s actually quite a lot of anxiety involved, it makes everyone look bad.

Oh, and one other huge impediment: nobody wants you for an ally when your complaint is that health insurance has gone up three times as fast as wages. Had housing been added to the Telegraph’s basket of middle-class goods, they would have seen that, for the older homeowner with a mortgage, the rise in other prices is offset somewhat by the very low interest rates. But they would also have seen that the “middle-class” renter, or even the renter who actually is middle class, is suffering rent rises with no respect to wages, insecurity of tenancy, crummy conditions and life-changingly large proportions of income going on housing costs – very similar conditions, in other words, to everyone else.

The extent to which we are all in this wage-stagnating, price-increasing swamp together is a question of age rather than class. A middle-class person coming out of university is part of the private personal debt boom; a middle-class person under 30 is a victim of the rentier economy. When you strip out the peculiar lottery-win of being over 40 in the housing market, you can see the picture more clearly: everyone who earns, now earns less, while, by incredible coincidence, the ratio between profit and wages has tipped in the shareholders’ favour.

It is deeply ingrained in our political culture that classes must be held in opposition to one another; and a confluence of interests between the middle and the bottom is only possible when the bottom tries to emulate or join the middle (sorry, did I say tries? Of course I meant aspires).

It cuts across the spectrum – on the left, you would never want to preach allegiance between the person hit by the bedroom tax and the person who can’t afford the second holiday. On the right, you would never admit that there was any systemic connection between falling wages for the bottom decile, and falling wages for the eighth.

But considering them together would make it easier to see the patterns: wage depression never conveniently stopped at the bottom 20%, there is little brake on corporate power, and credit is allowing prices in every sphere to peel away from earnings. These trends are obscured by the rather dated political determination that “the needy” must be interested in one kind of politics, and “the aspirational” a completely different kind. Better to acknowledge the similarities in the situations we all face.

What is a “middle-class” expense? According to the Daily Telegraph, after considerable dialogue with its own readers, the key items in the portfolio of the bourgeoisie are as follows: school fees, dental care, health insurance, holidays, wine (fine), new cars, holidays and “cultural activities”. The price rises in all these areas have been astronomical – health insurance has gone up by 51% over the past six years, school fees by 40% – while over the same period earnings in the double-average-wage bracket have gone down by 0.8%.

Private school fees are paid by 7% of the population; private health insurance is taken out by 11%. This isn’t really the middle: the determination to retain the term middle class for those who are actually wealthy is akin to the care with which the right wing never describes its views as rightwing, preferring “commonsense”. It is a constant project to reframe what is normal in the image of what is normal for one person in 10.

But actually, on this matter, the middle classes are pretty normal. Income has stagnated across every section of society apart from the top 1% (whom the Telegraph would probably call upper middle or well-to-do). GDP per capita is lower than it was seven years ago. “That,” said the economist Joseph Stiglitz in an interview on Sunday “is not a success.”

It’s hard for the wealthy to mobilise around their declining living standards. Their options are limited. When so much of your wealth is spent avoiding the social structures on which solidarity is based – education, the health service, our crap dentistry of international renown – who do you complain to? Who are you going to stand shoulder to shoulder with? Your outrage at the world is limited in its expression to your power as a consumer. That’s why the incredibly angry, bright pink man yelling at a BT helpline is such a staple of modern British sitcoms; as a guardian angel against feelings of impotence and injustice, BT can’t really help – even if it does answer the phone.

So there’s the stain of self-interest barring entry to the language and power and solace of unity. There’s also a huge amount of shame involved in being in debt or struggling, especially against the backdrop of assumption that privilege is somehow the result of a lifetime’s sound financial decisions.

There’s a public pressure not to mention declining living standards, because that would be to insult people whose living standards have declined to the point of being unable to eat. There’s also a private pressure, since the status of the affluent is, of course, rooted in the affluence – and if one breaks ranks to say there’s actually quite a lot of anxiety involved, it makes everyone look bad.

Oh, and one other huge impediment: nobody wants you for an ally when your complaint is that health insurance has gone up three times as fast as wages. Had housing been added to the Telegraph’s basket of middle-class goods, they would have seen that, for the older homeowner with a mortgage, the rise in other prices is offset somewhat by the very low interest rates. But they would also have seen that the “middle-class” renter, or even the renter who actually is middle class, is suffering rent rises with no respect to wages, insecurity of tenancy, crummy conditions and life-changingly large proportions of income going on housing costs – very similar conditions, in other words, to everyone else.

The extent to which we are all in this wage-stagnating, price-increasing swamp together is a question of age rather than class. A middle-class person coming out of university is part of the private personal debt boom; a middle-class person under 30 is a victim of the rentier economy. When you strip out the peculiar lottery-win of being over 40 in the housing market, you can see the picture more clearly: everyone who earns, now earns less, while, by incredible coincidence, the ratio between profit and wages has tipped in the shareholders’ favour.

It is deeply ingrained in our political culture that classes must be held in opposition to one another; and a confluence of interests between the middle and the bottom is only possible when the bottom tries to emulate or join the middle (sorry, did I say tries? Of course I meant aspires).

It cuts across the spectrum – on the left, you would never want to preach allegiance between the person hit by the bedroom tax and the person who can’t afford the second holiday. On the right, you would never admit that there was any systemic connection between falling wages for the bottom decile, and falling wages for the eighth.

But considering them together would make it easier to see the patterns: wage depression never conveniently stopped at the bottom 20%, there is little brake on corporate power, and credit is allowing prices in every sphere to peel away from earnings. These trends are obscured by the rather dated political determination that “the needy” must be interested in one kind of politics, and “the aspirational” a completely different kind. Better to acknowledge the similarities in the situations we all face.