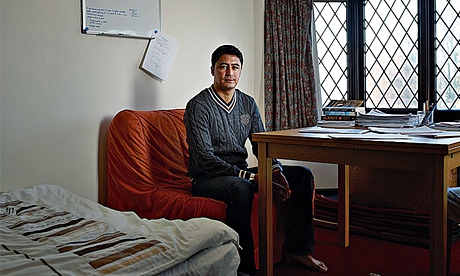

Wahid Ahmad, 33

Was: civil engineer, Afghanistan

Now: shelf stacker, north London

Wahid Ahmad trained as a civil engineer in Afghanistan, where he worked in a senior role for the UN on infrastructure projects, overseeing road- and bridge-building. "I was proud of the job I was doing, helping with the development of my country," he says. It was a well-paid job and very satisfying: the new roads he worked on helped farmers get produce to the markets more quickly and children to school more safely. But his role working for an international agency attracted disapproving attention from the Taliban and after receiving a series of threats, in 2008 Ahmad fled to the UK with his wife and two children.

For six months, while his asylum application was being considered, Ahmad was not allowed to work. He studied to pass high-level English language exams, so he could take a one-year post-graduate certificate in construction management. While studying, he worked part-time in a cafe, making pizzas, kebabs and burgers, and delivering takeaway meals.

When he started applying for engineering jobs, he was so discouraged by the constant rejections that he was prescribed antidepressants. Most of the time he gets no response to his applications, just an automated email that tells him to assume his application has been unsuccessful if he hears nothing back within four days. When he calls to ask why, despite his excellent qualifications, he has not been invited for an interview, he is told he has no UK experience. At this point, he often proposes that he volunteers with the company, but the offer is always rejected. "How am I to get experience if they won't even let me volunteer?"

He took on a job in a food shop, working first as a halal butcher and later on the shop floor. "For a while it was very new to me. I would be preparing the fruit and vegetables, and it would keep coming to my mind what I was and what I am now. To be honest, it made me cry, but I have no option but to continue. The people I work with are very kind. They know I am an educated person. They tell me, 'Please don't be sad. You will find a job in your own field eventually.'"

He has been getting support from a charity, Transitions, which helped him work on his CV, try to get work experience and stay positive. On his CV, under the section detailing his civil engineering experience, he summarises the skills he has gained in his new job: "Be attentive to customers' needs; handle the payment for any purchases; make the customer aware of any special offers."

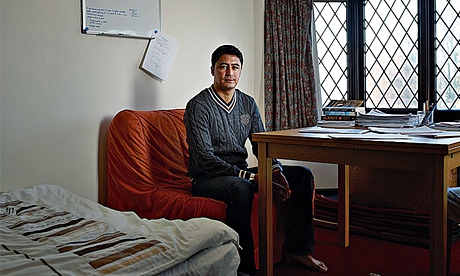

Iftikhar-ul-haq Khan, 46

Was: supreme court lawyer, Pakistan

Now: volunteer, Citizens Advice, Liverpool

In March 2010, Iftikhar-ul-haq Khan was dropping his children off at school when his car was stopped and he was kidnapped by a group hostile to the Ahmadiyya Muslim community to which he belongs. He was held for 19 days, in brutal conditions. As soon as he was released (upon the payment of a substantial ransom by his family), he made preparations to flee to England. It was clear to him that he and his wife and children would be in danger if they were to remain.

The transition was stark: "In Quetta, we had maids, a garden. We had a smooth life. In London, we shared one room in a bed and breakfast." It took almost two years before his asylum request was granted, during which time he was not allowed to work. "That was very difficult for me, particularly from a professional point of view." Once he was granted refugee status in October 2012 and began trying to find work, he was told that, without UK qualifications, his professional experience in Pakistan counted for little. "I was a legal adviser to the UN, to the National Bank of Pakistan." He worked on amending the Pakistan constitution and ran a private legal practice. To work here, he has to do an expensive legal conversion course. "After the course, I would need to start from scratch. People will still be asking what experience I have in this country. I achieved the highest level in my profession. Here I am at the beginning again."

The jobcentre is encouraging him to apply for work in the admin sector. "It feels a bit ridiculous. I had status, my own law firm, my profession. After three years here, I am in no man's land. I want to stand on my own two feet. I don't like being on benefits. I'm more used to helping others than taking help."

Khan has volunteered for Refugee Action and for the local Citizens Advice bureau. He enjoys it, but feels occasionally frustrated about the gulf between what he does now and what he once did. "I don't always think of myself as a supreme court lawyer. I try to give what I can. But sometimes it is in my mind that maybe I'm not doing the work I really should be doing."

His eldest daughter, 15, completed a two-year GCSE course in six months and got A*s, and a local newspaper interviewed her. "She made a contribution," Khan says. "We all want to give things back to this country. That makes me happy. I have no regrets. No complaints."

Agnes Tanoh, 57

Was: senior government adviser, Ivory Coast

Now: destitute asylum seeker, Birmingham

Agnes Tanoh, former government adviser on financial and social affairs in Ivory Coast, fled her country because she faced arrest and long-term imprisonment, after regime change pushed her to the wrong side of the political divide. Before the government fell, she worked for the first lady, as her aide, then as head of her administration. Three years after fleeing to England, Tanoh has swapped a five-bedroom house in Abidjan for a flat paid for by the charity Women for Refugee Women in Birmingham. Her initial claim for asylum has been rejected, which means she has no entitlement to benefits and gets only £20 a week from the Hope Projects, a local asylum charity; £15.50 of that goes on her bus pass, which allows her to travel to language classes; she feeds herself by picking up basic supplies once a month from a food bank.

Most of her family have fled Ivory Coast; her husband of 33 years is in Ghana, her four children scattered in different countries. But for the moment, what makes her unhappy is the enforced idleness: the UK Border Agency stipulates, in emphatic capitals, in correspondence with her, "You are NOT allowed to work."

"Work is health," she says, taking off her glasses and rubbing her eyes. "I started working when I was 21. I am an active person. When you have nothing to do, you look on your situation and start to think. You say to yourself: 'What am I doing? What will become of me?'"

Although she is not a qualified teacher, in Ivory Coast she founded and ran a secondary school. For a while, when she was in a hostel in Bolton, she volunteered with a charity and taught French to retired people. "I enjoyed it a lot. I felt I was bringing something to people."

Hasan Abdalla, 58

Was: academic and artist, Syria

Now: jobseeker, London

Hasan Abdalla had a well-equipped studio in the garden outside his Damascus flat; every morning he would walk past orange, apple, pear and pomegranate trees, to paint inside or in the open when the weather was fine. Now he paints in the bedroom of the south London bedsit where he has been living since he was granted asylum. It's much noisier, and he finds that the sounds from the Iceland loading station in front of the house and the railway tracks behind are often distracting. He has tried listening to music or singing to himself to drown out the noise, but on the whole it has been a difficult period for painting. He misses his wife and three sons, whom he hasn't seen since his hurried departure from Syria in July 2011. He finds London an inspirational place, but he also feels disoriented and alone.

Every stretch of wall in his small flat is covered with the artworks he managed to bring with him, and a few that he has done since arriving here. Beneath his bed he keeps rolled-up 3m canvases. The small kitchen table is covered with old newspaper, ready for him to start painting, but at the moment this happens rarely.

When you are dependent on jobseeker's allowance, painting is an expensive habit. In Syria, Abdalla regularly exhibited with two galleries, and made a good living from selling his work. But his reputation has not travelled with him, and although he has had pictures exhibited in three galleries here, he has sold very little. For three months he went by bus every Sunday to Bayswater Road, with as many paintings as he could carry, to try selling them on the park railings. It was a dispiriting experience, since the pictures got battered on the journey; and although passersby made appreciative comments, they rarely bought pictures.

In Syria and Libya, Abdalla sold his work for around £2,500. He has sold only four pictures since coming to England, each for a fraction of that price. Despite these difficulties, he knows that fleeing Syria, and paying an agent £20,000 of his savings, was the right thing to do. Two of his friends, who had been with him on a protest march in 2011, were shot by the authorities. He had spent time in prison in 2010, and been badly beaten. He was sacked from his job as a university lecturer because he failed security checks. Following his departure, his flat was searched and one of his sons arrested.

He has been supported by the Red Cross and thinks he is lucky to have ended up in England. "People are friendly. They try not to make you feel like a stranger."

Tiegisty Kibrom, 27

Was: IT graduate, Eritrea

Now: hotel cleaner, London

Tiegisty Kibrom graduated with distinction in her computer science degree and hoped to open a computer business. "I wanted to have my own shop, which would be open for people who had no access to computers – I could train people on them. There's a real need for places like that in Eritrea."

She fled after being persecuted for her religious beliefs. When she was gone, her mother was arrested and held for three weeks. She thinks that it would not be safe to return.

With her excellent degree, she thought it would be easy to find work here, but when she realised how hard it would be to get a job, she enrolled on a BSc in internet computing at Manchester Metropolitan University. Even after completing the course, she has not found work in computing; last autumn she took a job cleaning rooms in a five-star hotel near Hyde Park. She works an evening shift, is responsible for cleaning 45 rooms and is paid £6.31 an hour. "I was expecting I'd get a better job. I am not ashamed to do a cleaning job. It just embarrasses me that, with all my skills, I can't find a single opportunity to work in my field." The work is hard. "Sometimes you feel abused. They say: 'If you don't do this, we will sack you.' I have enough stress in my life. They say: 'You know, girls, you have to be more grateful. Some people don't have any jobs.'"

She has volunteered as a computer instructor in a refugee centre; ultimately, she would like to be a database assistant, but mostly her job applications are not acknowledged. "I'm a fast learner, I know I could do it if they gave me a chance," she says.

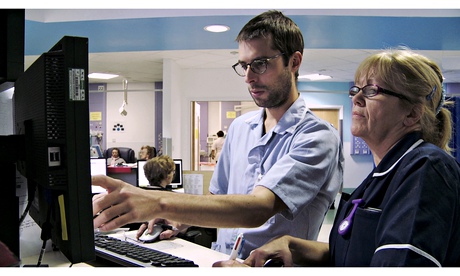

Helal Attayee, 30

Was: doctor, Afghanistan

Now: healthcare assistant, London

He was repeatedly targeted by local fundamentalists, who branded him a traitor and threatened his family. He decided it would be safer to leave the country for his medical training, and went to Turkey. Once he had qualified, he returned to Afghanistan to work as a doctor, but quickly realised his life was at risk. "The local fundamentalists, who became Taliban later, told me that I was helping the infidels," Attayee says. "They warned me that I should stop."

He was forced to flee to the UK. He has been supported by the Red Cross while he studies for a number of exams he must pass before he can take up his old career, including a very demanding English exam. His English sounds flawless to me (as you would expect from a former UN interpreter), but he has failed the exam three times already. Each time he has to retake it, he has to pay £145. His bedroom, in a shared flat in north London, is filled with books and test papers, and ahead of his next test, he has covered a whiteboard on the wall with words that he finds challenging.

Attayee is currently working as a locum phlebotomist, taking blood for testing. "To become a doctor, you have to study for six or seven years," he says. "For phlebotomy, you just have to complete a four-day course. Anyone can do it. It was very, very difficult to find a job, so I was lucky,. Phlebotomy is fine. I know that it is only temporary."