Some managers are wary of telling staff that going into a workplace has networking benefits writes Emma Jacobs in The FT

After weighing up the pros and cons of future working patterns, Dropbox decided against the hybrid model — when the working week is split between the office and home. “It has some pretty significant drawbacks,” says Melanie Collins, chief people officer. Uppermost is that it “could lead to issues with inclusion, or disparities with respect to performance or career trajectory”. In the end, the cloud storage and collaboration platform opted for a virtual-first policy, which prioritises remote work over the office.

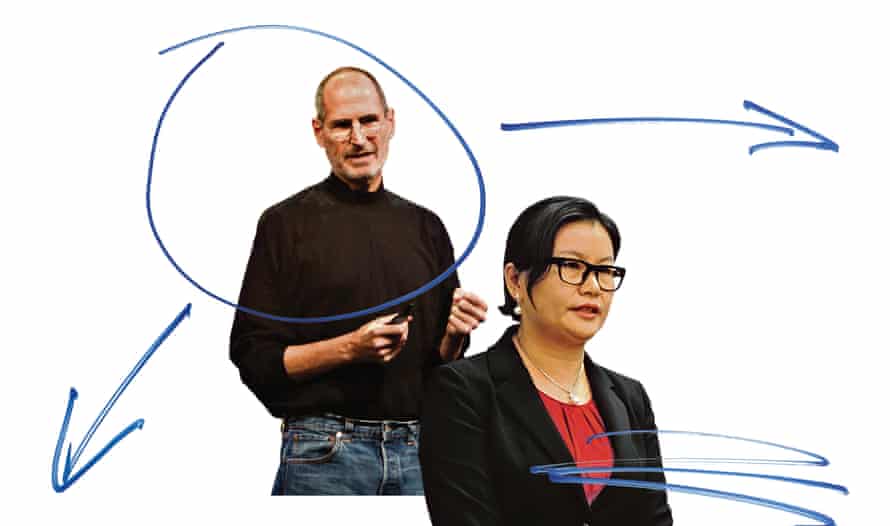

As offices open, there are fears that if hybrid is mismanaged, organisational power will revert to the workplace with executives forming in-office cliques and those employees who seek promotion and networking opportunities switching back to face time with senior staff as a way to advance their careers.

The office pecking order

Status-conscious workers may be itching to return to the office, says Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, professor of business psychology at Columbia University and UCL. “Humans are hierarchical by nature, and the office always conveyed status and hierarchy — car parking spots, cars, corner office, size, windows. The risk now is that, in a fully hybrid and flexible world, status ends up positively correlated with the number of days at the office.”

This could create a two-tier workforce: those who want flexibility to work from home — notably those with caring responsibilities — and those who gravitate towards the office. Rosie Campbell, professor of politics and director of the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership at King’s College London, says that past research has shown that “part-time or remote workers tend not to get promoted”. This has been described as the “flexibility stigma, defined as the “discrimination and negative perception towards workers who work flexibly, and [consequent] negative career outcomes”.

Research by Heejung Chung, reader in sociology and social policy at Kent University, carried out before the pandemic, found that “women, especially mothers (of children below 12) [were] likely to have experienced some sort of negative career consequence due to flexible working”. Lockdowns disproportionately increased caring responsibilities for women, through home-schooling and closure of childcare facilities.

Missing out on career development

Some companies are creating regional hubs or leasing local co-working spaces so that workers can go to offices closer to home, reducing commute times and the costs of expensive office space. Lloyds Banking Group is among a number of banks, for example, that have said they will use surplus space in their branches for meetings. The risk, Campbell says, is workers using local offices miss out on exposure to senior leaders and larger networks that might advance their careers. “People might say it’s easier to be at home or use suburban hubs but it might actually be better to go into the office. Regional or suburban hubs are giving you a place to work that isn’t at home but isn’t giving you any of the face time.”

Employers and team leaders may need to be explicit about the purpose of the office: not only is it a good place for collaborating with teams and serendipitous conversations but also for networking.

Mark Mortensen, associate professor of organisational behaviour at Insead, points out it is difficult — and paternalistic — as a manager to suggest an employee spends more time in the office to boost their career. A recent opinion article by Cathy Merrill, chief executive of Washingtonian Media, in the Washington Post, sparked a huge backlash on social media and more importantly, her employees, for arguing that those who do not return to the office might find themselves out of a job. “The hardest people to let go are the ones you know,” she wrote.

Her staff felt their remote work had been unappreciated and were angry that they had not been consulted over future work plans — so they went on strike.

Mortensen does not advise presenting staff with job loss threats, but puts forward a case for frank and open conversations about the value of time in the office. “Informal networks aren’t just nice to have, they are important. We need to tell people the risk is if you are working remotely you will be missing out on something that might prove beneficial in your career. It’s tough. People will say they sell things on their skills but you have to be honest and say that relationships are important. Weak ties can be the most critical in shaping people’s career paths.”

The problem is that after dealing with a pandemic and lockdowns, workers may not be in the best place to know what they want out of future work patterns. Chamorro-Premuzic says that he fears that even people who are enjoying it right now, may not realise “they are burnt out. It’s like the introvert who likes working from home, they’re playing to their strength — staying in their own comfort zone.”

Examine workplace culture

As employers try to configure ways of working they need to scrutinise workplace culture and find out why employees might prefer to be at home. Some will have always felt excluded from networks and sponsorship in the office — and being away from it means that they do not have to think about it.

Future Forum, Slack’s future of work think-tank, found that black knowledge workers were more likely to prefer a hybrid or remote work model because the office was a frequent reminder “of their outsider status in both subtle (microaggressions) and not-so-subtle (overt discrimination) ways”. It said the solution was not to give “black employees the ability to work from home, while white executives return to old habits [but] about fundamentally changing your own ways of working and holding people accountable for driving inclusivity in your workplace”.

Some experts believe that the pandemic has fundamentally altered workplace behaviour. Tsedal Neeley, professor of business administration at Harvard Business School and author of Remote Work Revolution, is optimistic. “Individuals are worried about their career trajectory because the paranoia is, ‘If we don’t go to the office will we get the same opportunities and career mobility if we’re not physically in the office?’ These would be very legitimate worries 13 months ago but less of a concern now.”

Chung co-authored a report by Birmingham University that found more fathers taking on caring responsibilities and an increase in the “number of couples who indicate that they have shared housework [and] care activities during lockdown”. This might shift couples’ attitudes to splitting work and home duties and alter employers’ stigmatisation of flexible working.

Prevent an in-crowd

There are some measures that employers can take to try to prevent office cliques forming. Some workplaces will require teams to come in on the same days so employees get access to their manager, rather than leaving it to individuals to arrange their own office schedules. Though this would mean team members might not get access to senior leaders or form ties with other teams that they might have done when the office was the default.

Lauren Pasquarella Daley, senior director of women and the future of work at Catalyst, a non-profit that advocates for women at work, says senior executives need to be “intentional about sponsorship and mentoring” rather than letting these relationships form by chance.

They must also be role models for flexible working. “If employees don’t feel it’s OK to take advantage of remote work then they won’t do so.” This means ensuring meetings are documented. If, for example, one person is working outside the office then everyone needs to act as if they are remote, too.

Chamorro-Premuzic says managers should work on the assumption that in-office cliques will form. This means organisations need to put in place better measures of objectives, performance measures independent of where people are, as well as measuring and monitoring bias (for example, if you know how often people come to work, you can test whether there is a correlation between being at work and getting a positive performance review, which would suggest bias or adverse impact), and training leaders and managers on how to be inclusive.

“We may not have tonnes of data on the disparate impact of hybrid policies on underprivileged groups, but it is naive to assume it won’t happen. The big question is how to mitigate it,” he says.

A rewarding alternative … volunteers working at a foodbank in Earlsfield, south London. Photograph: Charlotte White/PA

A rewarding alternative … volunteers working at a foodbank in Earlsfield, south London. Photograph: Charlotte White/PA