'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label violence. Show all posts

Showing posts with label violence. Show all posts

Tuesday, 24 March 2015

Saturday, 24 January 2015

Why don’t abused women just leave their partners? Why don’t poor people just spend less? Why do people in positions of power ask so many stupid questions?

Lucy Mangan in The Guardian

Last week, I took part in a comedy night to raise money for the charity Refuge, which supports women and children who have experienced domestic violence. It was a great night: partly because it raised several thousands of pounds for the cause; partly because it was sponsored by Benefit cosmetics, and the idea of a benefit being sponsored by Benefit pleased me greatly; and partly because standup comedian Bridget Christie finished her act with a plea for all laydeez to stop waxing, spraying, deodorising, strimming and surgically trimming their – well, let’s call it “that part of ourselves historically judged to be the seat of all our femininity and womanly powers” – and instead celebrate our individuality by thinking of those parts as “unique, special – like snowflakes. Made of gammon”, which was both a new thought and a new image, neither of which has left my mind since.

Less uplifting, however, was the number of times I heard, when I mentioned Refuge to people, some variant of: “But what I don’t understand is – why don’t these women just leave?”

We don’t need, I think – I hope – to detail too extensively here the exact answer to that question. Bullet points: an immediate fear of being punched, kicked, bitten, gouged or killed, and of the same happening to your children, preceded by months or years of exploitation of the weakest points in your psyche by a master of the art; an erosion of your self-confidence, liberty, agency and financial independence (if you had any to begin with), coupled with a sense of shame and stigma and a lack of practical options; no money, no supportive family or friends, nowhere to run.

So, let’s concentrate instead on the lack of imagination, the lack of empathy inherent in that question. Because it shapes a lot of questions, and particularly those that animate government policy and the political discourse that will start filling the airwaves more and more as we move towards the election.

Politicians, for example, are apparently completely baffled by Poor People’s propensity to do harmful things, often expensively, to themselves. (That’s politicians of all stripes – it’s just that the left wing wrings its hands and feels helplessly sorry for Them, while Tories are pretty sure They are just animals in need of better training.) The underclass eats fast food, drinks and smokes, and some of its more unruly members even take drugs. Why? Why?

Listen, I always want to say, if you’re genuinely mystified, answer me this: have you never had a really bad day and really wanted – nay, needed – an extra glass of Montrachet on the roof terrace in the evening? Or such a chaotic, miserable week that you’ve ended up with a takeaway five nights out of seven instead of delving into Nigella’s latest?

You have? Why, splendid. Now imagine if your whole life were not just like that one bad day, but even worse. All the time. No let-up. No end in sight. No, you can’t go on holiday. No, you can’t cash anything in and retire. No. How would you react? No, you’ve not got a marketable skills set. You don’t know anyone who can give you a job. No. No.

And on we’d go. “Why do the poor not always take the very cheapest option – in food, travel, rent, utilities or a hundred other things you can find if you or an obliging Spad or unpaid intern trawl and filter case studies for long enough – and stop being so, y’know, poor that way?” someone will ask. And some kind soul – not me, I’d be off for a lie down and some pills by this time – would ask if the questioner had ever been under so much pressure that he’d had to throw money at a problem to secure an immediate answer, to get something rather than nothing, even if it meant paying over the odds, perhaps because someone was exploiting your desperation?

Oh, you have? Well, that bond issue you missed because you had a cashflow crisis after buying the villa in Amalfi, and that box at Glyndebourne for your parents’ wedding anniversary you forgot about till almost too late, have their parallels with furniture for a council flat or with a child’s present bought on punitively interest-rated credit … and so on, until somewhere along the line our boy would have to admit that he shared the same irrational impulses as people all along the socioeconomic scale, differing only in degree of consequences, not in kind.

I don’t understand how the people in charge of us all don’t understand. If you are genuinely unable to apply your imagination and extend your empathy far enough – and you don’t have to do it all at once; little by little will suffice, but you must get there – then you are a sociopath, and we should all be protected from your actions. If you are in fact able and choose not to, then you’re something quite a lot worse.

So, these are the questions I’d like to see pursued once the televised prime ministerial debates begin (if enough speakers agree to turn up, natch): have you ever had a bad day? Have you ever been really, really tired? Have you ever been alone, or frightened, or not had a choice about something? If yes, was your response unique among man? If no, are you a madman or a liar? Do tell. Do tell.

Friday, 16 January 2015

Perspective on Charlie Hebdo, Peshawar killings; In maya, the killer and the killed

Jan 14, 2015 12:21 AM , By Devdutt Pattanaik in The Hindu |

Emotional violence is not measurable. Physical violence is, which makes it a crime that can be proven and hence a greater crime, especially when emotional violence is directed at something as notional as religion

When the Pandavas invited Krishna to be the chief guest at the coronation of Yudhishtira, Shishupala felt insulted and began abusing Krishna. Everyone became upset, but not Krishna who was listening calmly. However, after the hundredth insult, Krishna hurled his razor-sharp discus and beheaded Shishupala. For the limit of forgiveness was up.

Charlie Hebdo, a French satirical weekly, published cartoons; offensive cartoons that I have never seen, and would never have, had someone not killed its staff. With that Charlie became a person, a victim, a martyr to the cause of the freedom of expression. We became heroes by condemning the killing. And so millions have walked in Paris to declare that they are Charlie.

Will there be a march where people identify themselves with Charlie’s killers? Is that allowed? Who are the killers? Muslim, bad Muslim, mad Muslim, un-Islamic Muslim? The editorials are undecided, as in the attack in Peshawar on schoolchildren. The victims there did not even provoke; their parents probably did.

The provocation in Charlie’s case was this: perceived insult to the Prophet Muhammad, hence Islam. Charlie, however, was functioning within the laws of a land renowned for the phrase, “Liberty, Equality and Brotherhood!” Islam is also about brotherhood (Ummah, in Arabic) and equality, though not so much about liberty since Islam does mean submission, a submission to the word of god that brings peace.

Managing the measurable

The two siblings, believers in equality and their own version of liberty decided to hurt each other, one emotionally, the other physically. Emotional violence is not measurable. Physical violence is. That makes the latter a crime that can be proven, hence a greater crime, especially when emotional violence is directed at something as notional as religion. Because we are scientific, you see.

The two siblings, believers in equality and their own version of liberty decided to hurt each other, one emotionally, the other physically. Emotional violence is not measurable. Physical violence is. That makes the latter a crime that can be proven, hence a greater crime, especially when emotional violence is directed at something as notional as religion. Because we are scientific, you see.

And here is the problem — measurement, that cornerstone of science and objectivity.

We can manage the measurable. But what about the non-measurable? Does it matter at all? Emotions cannot be measured. The mind cannot be measured, which is why purists refer to psychology and behavioural science as pseudoscience. God cannot be measured. For the scientist, god is therefore not fact. It is at best a notion. This annoys the Muslim, for he/she believes in god, and for him/her god is fact, not measurable fact, but fact nevertheless. It is subjective truth. My truth. Does it matter?

Where do we locate subjective truth: as fact or fiction? Some people have given themselves the “Freedom of Expression” and others have given themselves a “God, who is the one True God.” Both are subjective truths. They shape our reality. They matter. But we just do not know how to locate them, for they are not measurable.

We cannot measure the hurt Charlie’s cartoons caused the Muslim community. We cannot measure the Muslim community’s sensitivity or over-sensitivity. But we can measure the outcome of the actions of the killers. We can therefore easily condemn violence. That it caused hurt, rage, humiliation, enough for some people to grab guns, is a non-measurable assumption, a belief. Belief is a joke for the rational atheist.

The intellectual can hurt with his/her words. The soldier can hurt with his/her weapons. We live in the world where the former is acceptable, even encouraged. The latter is not. It is a neo-Brahminism that the global village has adopted. Those who think and speak are superior to those who beat and kill, even if the wounds created by word-missiles can be deeper, last longer and fester forever. Gandhi, the non-violent sage, is thus pitted against Godse, the violent brute. I, the intellectual, have the right to provoke; but you, the barbarian who only knows to wield violence, have no right to get provoked and respond the only way you know how to. If you do get provoked, you have to respond in my language, not yours, brain not brawn, because the brain is superior. I, the intellectual Brahmin, make the rules. Did you not know that?

Non-violence is the new god, the one true god. When we say violence, we are actually referring only to the physical violence of the barbarian. The mental violence of the intellectual elite is not considered violence. So, one has sanction to mock Hinduism intellectually on film (PK by Rajkumar Hirani and Aamir Khan) and in books (The Hindus: An Alternative History by Wendy Doniger), but those who demand the film be banned and the books be pulped are brutes, barbarians, enemies of civic discourse, who resort to violence. They are not as bad as the Charlie killers, but seem to be on the same path.

Role of the thinker

We refuse to see arguments as brutal bloodless warfare, mental warfare. We don’t see debating societies as battlegrounds. Mental torture, we are told, is merely a concept, not truth: difficult to measure hence prove. The husband who mentally tortures can never be caught; the husband who strikes the wife can be caught. We empathise with the latter, not the former (she is over-sensitive, we rationalise). Should the mentally tortured wife kill her husband, it is she who will be hauled to jail, not the husband. Her crime can be proved. Not his.

We refuse to see arguments as brutal bloodless warfare, mental warfare. We don’t see debating societies as battlegrounds. Mental torture, we are told, is merely a concept, not truth: difficult to measure hence prove. The husband who mentally tortures can never be caught; the husband who strikes the wife can be caught. We empathise with the latter, not the former (she is over-sensitive, we rationalise). Should the mentally tortured wife kill her husband, it is she who will be hauled to jail, not the husband. Her crime can be proved. Not his.

The thinker we are told is not a doer. The killings provoked by the thinker thus goes unnoticed. The thinker — the seed of the violence — chuckles as the barbarian, whose only vocabulary is physical, will be caught and punished while mental warfare will go on with brutal precision. When the ill-equipped barbarian even attempts to fight back using words, we mock him as the troll.

In Sanskrit, the root of the world maya is ma, to measure. We translate the word as illusion or delusion but it technically means a world constructed through measurement. Thus, the scientific word, the rational world, based on measurement, is maya. And that is neither a good or bad thing. It is not a judgement. It is an observation. A world based on measurement will focus on the tangible and lose perspective of the intangible. It will assume measured truth as Truth, rather than limited truth.

Those who felt gleeful self-righteousness in mocking the Prophet are in maya. So are those who took such serious offence to it. The killer is in maya and so is the killed. Those who judge one as the victim and the other as the villain are also in maya. We all live in our constructed realities, some based on measurement, some indifferent to measurement, each one eager to dismiss the other, rendering them irrelevant: The other is the barbarian who needs to be educated. The other is also the intellectual who is best killed.

Essentially, maya makes us to judge. For when we measure, we wonder which is small and what is big, what is up and what is down, what is right and what is wrong, what matters and what does not matter. Different measuring scales lead to different judgments. Wendy Doniger is convinced she is the hero, and martyr, who fights for the subaltern Indian in her writings. Dinanath Batra is convinced he is the hero who opposes her wilful misunderstanding of sanatana dharma. Baba Ramdev feels he has a right to demand the banning of PK. And the producers of the film respond predictably about the freedom of speech and rationality, as they laugh their way to the bank. Everyone is right, in his or her maya.

Every action has consequences. And consequences are good and bad only in hindsight. The age of Enlightenment was also the age of Colonisation. The most brutal wars of the 20th century, from the world wars to the Cold Wars, were secular. Non-violent thought manifests itself in non-violent words which give rise to violent action. The fruit is measurable, not the seed. To separate seed from fruit, thought from action, is like separating stimulus from response. It results in a wrong diagnosis and a wrong prescription. The killer does not kill thought. The thought creates more killers.

What goes around always comes around. Outrage over violence feeds outrage over cartoons. Hindu philosophy (not Hindutva philosophy) calls this karma. We don’t want to break the cycle by letting go of either non-violent outrage or violent protests. Ideas such as maya and karma annoy the westernised mind for they disempower them: they who are determined to save the world with measuring tools dismiss astute observation of the human condition as fatalism.

In his past life, Shishupala was the doorkeeper Jaya of Vaikuntha who was cursed by the Sanat rishis that he would be born on earth, away from Vishnu, for daring to block their entry. The doorkeeper Jaya argued that he was doing his job but the curse stuck and Jaya was reborn as Shishupala. Vishnu had promised to liberate him and to expedite his departure, Shishupala practised viparit-bhakti, reverse-devotion, displaying love through abuse. So he insulted Krishna, knowing full well that Krishna was Vishnu and would be forced to act. There is a limit to forgiveness. But there should be no limit to love.

Sunday, 28 December 2014

Cricket - enough with the onfield chatter

There's a difference between gamesmanship and verbal intimidation; the former adds colour and humour to the game, the latter breeds hostility © AFP

Ian Chappell in Cricinfo

On-field chatter was on the agenda again after the Gabba Test. The question being asked was: Why did India taunt Mitchell Johnson? The more important question is: Why does cricket allow so much on-field chatter?

The more players talk on the field, the more the likelihood there is of something personal being said. If something personal is said at the wrong time, there will eventually be an altercation on the field. When that happens it will be players who are punished and as is almost always the case, the administrators will escape scot-free, despite being guilty of allowing the problem to escalate to this point.

Apart from the danger of an altercation on the field - and if you don't think that could be ugly, just remember two players have bats in hand - there is the simple matter of the batsman being entitled to peace and quiet while he's out in the middle. I'm surprised more batsmen don't object to the inane chatter that regularly occurs in the guise of gamesmanship. And if I hear one more player, coach or official say this chatter is "part of the game", I'll lose my lunch.

What will happen if a batsman - and the sooner one summons up the courage to do so the better - starts talking to the bowler as he begins his run to the wicket? Will he be told by the umpire to desist? Sure he will. The batsman would then be entitled to ask the umpire: "So is only one team allowed to talk out here?" Perhaps it will take such a scenario to make the administrators realise this is not an acceptable part of the game. The issue needs to be addressed seriously and promptly.

I don't have any problem with gamesmanship. This is the thoughtful and often humorous use of wit to entice an unsuspecting player into losing his concentration. When bowling into the footmarks to Sourav Ganguly from round the wicket, Shane Warne provided a classic example of gamesmanship. After Ganguly had let a couple of balls go, Warne remarked; "Hey mate, the crowd didn't pay their money to watch you let balls go. They came here to see this little bloke [pointing to Sachin Tendulkar at the non-striker's end] play shots."

If a batsman is silly enough to fall for such a ploy then more fool him. Gamesmanship has been part of cricket since its inception and it's also been responsible for a lot of the humour that adds colour to the descriptions of the contest. There's a big difference between gamesmanship and personal abuse, or the constant inane chatter fielders use to try to distract batsmen.

Any abuse should result in the offender being spoken to in no uncertain terms by the umpires. If it continues then the offender should be hit with a substantial suspension, one that will cause him and other players to think twice before they mouth off again. And umpires should be told by the administrators that they will be backed to the hilt in an endeavour to rid the game of both abuse and excessive chatter.

One of the big mistakes touring sides make is trying to play Australia at their own game. There has always been a bit of needling/gamesmanship in the Australian first-class game because the players know each other so well.

However, in the past this was laughed off after play with the aid of a cold drink, and the next day's play commenced with a clean slate. As socialising after play doesn't often occur so much now in the international game, the previous day's hostilities are still fresh the next morning and it doesn't take much to re-ignite the fuse.

India made a mistake in taunting Johnson at the Gabba. The administrators will be making an even bigger blunder if they don't crack down on excessive on-field chatter, and it's the players who will pay a hefty price if this issue is left unresolved.

Tuesday, 9 December 2014

Anni Dewani has been failed by South Africa

She died alone and terrified in one of the bleakest parts of the country, and after the collapse of Shrien Dewani’s trial her family still has no answers

- Margie Orford in The Guardian

Anni Dewani, a young woman shot dead in Cape Town, has haunted South Africa for four years. After the collapse of the trial of her husband, Shrien Dewani, accused of masterminding her murder, she will continue to do so. Not only because she was young, beautiful and just married; not only because her heartbroken, desperate parents have been taken into so many South African hearts; but also because the country, its police force and its justice system failed her so completely.

Anni and Shrien honeymooned in South Africa after an extravagant wedding in India in 2010. After going on safari they came to Cape Town and, on Saturday 13 November, went out for dinner. On their return their taxi was hijacked. The taxi driver, Zolo Tongo, and Shrien claimed they were forced out of the car and that the hijackers drove off with Anni. Her body was found in the abandoned vehicle at dawn the next day. She had been shot at close range in the neck.

Shrien was apparently a victim of the criminal violence that plagues South Africa. The police, goaded as they were by the press frenzy, were under huge pressure to find the killers because hijacking and murder are so commonplace, but there were anomalies from the start. Gugulethu, where the hijacking occurred, is notorious for its murder rate. Why would Tongo take them there at night? Shrien, allegedly forced through a window, did not have a scratch on him, and neither did Tongo.

Whispers of disbelief quickly began to swirl. Shrien looked less and less innocent as detectives and journalists picked apart the sequence of events described, and the statements he had made. The police, however, allowed him to return to England before the inconsistent aspects of the case – and his possible involvement in his wife’s murder – were properly investigated.

Tongo was soon arrested. He pleaded guilty to being party to the murder but, in return for a reduction of sentence, said he would tell the truth and claimed that Shrien had asked him to organise the killing. The hitmen, Mziwamadoda Qwabe and Xolile Mngeni, were subsequently arrested, tried and jailed. Monde Mbolombo, the receptionist at the luxury Cape Grace hotel where the Dewanis were staying, said that he had put Tongo in contact with the hitmen. In exchange for immunity from prosecution – now under review due to the case collapsing – he agreed to testify against Shrien.

The idea of hiring people to commit murder is not that shocking in South Africa. Firearms are cheap and easy to find, as are hitmen. In 2006 a young woman, Dina Rodrigues, went to a taxi rank in Cape Town and hired four strangers to murder the baby daughter of her boyfriend’s ex-girlfriend. She paid a similar amount to that which Tongo claimed Shrien paid.

It is notable that Anni’s murder took place just four months after South Africa had successfully hosted the football World Cup, when the country was under intense scrutiny because of its record of violent crime. This coloured the investigation from the start.

The then-commissioner of police, Bheki Cele, is reported to have said: “A monkey came all the way from London to have his wife murdered here. Shrien thought we South Africans were stupid.” There seemed to be a great sense of relief that responsibility for this awful murder, a public relations disaster for South Africa, lay elsewhere.

Shrien was charged and four years later returned to stand trial. Everyone seemed to have a view on his innocence or guilt. It was revealed early on that perfect wedding photographs masked Anni’s doubts about marrying Shrien. There were sensational revelations about Shrien’s bisexuality and his involvement, both online and offline, in sadomasochistic sex with male prostitutes. “At last,” people thought, “a clear motive!”

Shrien’s sexual orientation and sexual practices clearly indicated a double life. But when put forward by the lacklustre prosecution as the reason for the murder, the judge, Janet Traverso, ruled this testimony irrelevant and the state’s case unravelled rapidly. This may not have been a popular move, but prejudice about a gay lifestyle should not subvert the need for hard evidence.

During the trial it became apparent that the investigation had been botched, and that much of the police work had been shockingly incompetent: lost paperwork, incomplete statements and unreliable ballistics reports.

Traverso chastised the National Prosecuting Authority. “You have had four years to prepare,” she told them when she dismissed the case. The evidence of the main witnesses was “riddled with contradictions” and fell “far below the threshold” of what a reasonable court could convict on.

Anni’s family, the Hindochas, have said that they – and by implication Anni – have been failed by South Africa’s justice system. They are right. Their daughter came here on her honeymoon and died alone and terrified in one of the bleakest parts of the country. Her grieving relatives have sought answers, as have South Africans.

In a country with such high levels of violence, there are so many who have failed to receive a robust investigation followed by the satisfaction of justice. As the Hindochas stood tearfully outside the courtroom after the verdict, there would have been so many South Africans sharing the family’s anguish at not knowing how or why a loved one died.

Monday, 10 November 2014

It’s economics, stupid - Denying legality to sex work in fact worsens the exploitation

Bachi Karkaria in the Times of India

In 1938, a book hit British stands and smugness — To Beg I Am Ashamed: A Frank and Unusual Autobiography by Sheila Cousins, a London prostitute. It was ghostwritten by Ronald Matthews, with considerable inputs from his more celebrated pub chum, Graham Greene. It was prematurely ejaculated from bookshops under pressure from the home secretary, whose hand was forced by the Public Morality Council. A ‘handsome, sound and tight copy’ of the first edition came recently on the market, priced at $13,165, not only because it was in ‘fine condition’ but because the book’s hasty withdrawal had made it extremely rare.

A less welcome development on the same subject has resurfaced in India where, even in the 21st century, we still get our knickers in a twist whenever the uncomfortable fact of prostitution is forced upon our delicate (read hypocritical) sensibilities.

One seldom agrees with Lalitha Kumaramangalam when, as BJP-appointed chairperson of the National Commission for Women, she defends the indefensible sexist statements of the Sangh Parivar’s rabid rump. But her recent support for legalising sex work makes eminent sense. Predictably, it has led to a decibel level of protest louder than a brothel brawl.

To see, understand and finally accept the merits of such legalisation, we first need to make two clear demarcations. One, we have to rid our minds of the semantic baggage of ‘prostitute’ (or whore, harlot, fallen woman); the noun has become a hiss verb outside its native place. Its loaded subtext of immorality of any stripe puts a mental block in the way of accepting sex work as economic activity — which is precisely what it is for these women (and men and transgenders) grappling with their no-exit destiny.

Two, we need to separate the desirable idea of legalising sex work from the reprehensible idea of legalising exploitation. It is nobody’s case that we legitimise abduction and abuse. But the opponents of legalised sex work deploy this sophistry, mixing up these two entities. We need to fight the predator trafficker and pimp, not their prey. Yes, we have to punish abusive clients too, but, get real guys, in which Utopian age can we seriously expect to implement what the UN’s Palermo Protocols grandly call a ‘demand reduction’ strategy? Abuse reduction is more important, and arguably more doable.

It is the world’s oldest profession, remember? And the need for commercially provided sex hasn’t noticeably changed, despite a range of onslaughts ranging from the fire-and-brimstone brigade to AIDS. Or there’s the Khushwant Singh solution. Addressing a conference called to ‘eradicate prostitution’ in the early 1970s, the irreverent sardar told the starched and genteel assembly, “This will happen only when the amateur drives out the professional.”

More seriously, while tracking the emerging AIDS epidemic in the 1990s, my experience of Mumbai’s sordid red-light district was something of an epiphany, stripping me of my own ignorant prejudice and pettiness. Women have ended up here from various situations — abducted, abandoned, serially sold, or just plain impoverished — but for them this is now work, using their only sweat equity to keep body and soul together, children in school, parents in medicine, whole families in the ‘decency’ which holier-than-thou lofty society denies these breadwinners.

In those AIDS-decimating times, brothels were trapped between life and livelihood. In the early years, they were in denial; madams refused even to put up the NACO posters on safe sex, afraid these would stamp their establishment with HIV’s taint, and scare away clients. Later, there was no hiding from the grim toll which halved the population of those infamous cages.

The new stigma and the prostitute’s ages-old pariah-fication proved a lethal cross-infection, denying them medical help. If legal safeguards had been in place, they would not have been thrown on to the even meaner street, slipped off the radar of surveillance, been forced to sell themselves cheaper — and with no clout to insist on condoms, infected clients who then took HIV home to unwitting wives and unborn children.

So i don’t buy the argument of feminist columnist Rami Chhabra on this page last week which talked of ‘powerful foreign donors (who) backed prostitution’. Yes, there were condom-centric programmes because prophylactics were easier to hand out rather than the more-laborious behaviour change. But this is a cynical argument because condoms — compulsorily and correctly used by high-risk communities — were the first line of defence. The red-haired Australian Cheryl Overs, who switched to law to fight AIDS gave me a pithy quote: ‘A condom is to a brothel what a hard hat is to a construction site: essential safety equipment.’

One can ignore the sanctimonious unwashed who persist with the immorality argument and/or are in unredeemable denial about the sexual ‘need’ of the client, let alone the less escapable economic one of the prostitute. There’s even one lot which denounces the term ‘sex worker’ because it ‘debases legitimate workers’.

But what’s the excuse of aware feminists who refuse to accept the economic reality, spout ‘bodily integrity’ and continue to oppose legalisation on grounds of exploitation? Be logical ladies, if we don’t provide that vital umbrella, how can the sex worker challenge the sexual violence which rains down on her with such impunity?

Sunday, 2 November 2014

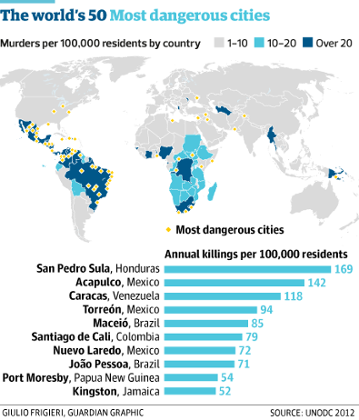

Murder capitals of the world: how runaway urban growth fuels violence

San Pedro Sula, Honduras, is the most dangerous city on the planet – and experts say it is a sign of a global epidemic

- John Vidal, environment editor

- The Observer,

It was relatively quiet in San Pedro Sula last month. A gunfight between police and a drug gang left a 15-year-old boy dead; the body of a man riddled with bullets was found in a banana plantation; two lawyers were gunned down; a salesman was murdered inside his 4x4; and a father and son were murdered at home after pleading not to be killed.

----Also read

----Also read

Humanity's 'inexorable' population growth is so rapid that even a global catastrophe wouldn't stop it

-----

One politician survived an assassination attempt and around a dozen people were found dead in the street. The number of killings is said to have fallen in the last few months, but the Honduran city is officially the most violent in the world outside the Middle East and warzones, with more than 1,200 killings in a year, according to statistics for 2011 and 2012. Its murder rate of 169 per 100,000 people far surpasses anything in North America or much larger cities such as Johannesburg, Lagos or São Paulo. London, by contrast, has just 1.3 murders per 100,000 people.

Now research by security and development groups suggests that the violence plaguing San Pedro Sula – a city of just over a million, and Honduras’s second largest – and many other Latin American and African cities may be linked not just to the drug trade, extortion and illegal migration, but to the breakneck speed at which urban areas have grown in the last 20 years.

The faster cities grow, the more likely it is that the civic authorities will lose control and armed gangs will take over urban organisation, says Robert Muggah, research director at the Igarapé Institute in Brazil.

“Like the fragile state, the fragile city has arrived. The speed and acceleration of unregulated urbanisation is now the major factor in urban violence. A rapid influx of people overwhelms the public response,” he adds. “Urbanisation has a disorganising effect and creates spaces for violence to flourish,” he writes in a new essay in the journal Environment and Urbanization.

Muggah predicts that similar violence will inevitably spread to hundreds of other “fragile” cities now burgeoning in the developing world. Some, he argues, are already experiencing epidemic rates of violence. “Runaway growth makes them suffer levels of civic violence on a par with war-torn [cities such as] Juba, Mogadishu and Damascus,” he writes. “Places like Ciudad Juárez, Medellín and Port au Prince … are becoming synonymous with a new kind of fragility with severe humanitarian implications.”

Simon Reid-Henry, of the Peace Research Institute in Oslo, said: “Today’s wars are more likely to be civil wars and conflict is increasingly likely to be urban. Criminal violence and armed conflict are increasingly hard to distinguish from one another in different parts of the world.”

The latest UN data shows that many cities may be as dangerous as war zones. While nearly 60,000 people die in wars every year, an estimated 480,000 are killed, mostly by guns, in cities. This suggests that humanitarian groups, which have traditionally focused on working in war zones, may need to change their priorities, argues Kevin Savage, a former researcher with the Overseas Development Institute in London.

“Some urban zones are fast becoming new territories of conflict and violence. Chronically violent cities like Abidjan, Baghdad, Kingston, Nablus, Grozny and Mogadishu are all synonyms for a new kind of armed conflict,” he said. “These urban centres are experiencing a variation of warfare, often in densely populated slums and shantytowns. All of them feature pitched battles between state and non-state armed groups and among armed groups themselves.”

European and North American cities, which mostly grew over 150 or more years, are thought unlikely to physically expand much in the next few decades and are likely to remain relatively safe; but urban violence is certain to worsen as African, Asian and Latin American cities swell with population growth and an unprecedented number of people move in from rural areas.

More than half the world now lives in cities compared with about 5% a century ago, and UN experts expect more than 70% of the world’s population to be living in urban areas within 30 years.

The fastest transition to cities is now occurring in Asia, where the number of city dwellers is expected to double by 2030, according to the UN Population Fund. Africa is expected to add 440 million people to its cities by then and Latin America and the Caribbean nearly 200 million. Rural populations are expected to decrease worldwide by 28 million people. Most urban growth is expected to be not in the world’s mega-cities of more than 10 million people, but in smaller cities like San Pedro Sula.

“We can expect no slowing down of urbanisation over the next 30 years. The youth bulge will go on and 90% of the growth will happen in the south,” said Muggah.

But he and other researchers have found that urban violence is not linked to poverty so much as inequality and impunity from the law – both of which may encourage lawlessness. “Many places are poor, but not violent. Some favelas in Brazil are among the safest places,” he said. “Slums are often far less dangerous than believed. There is often a disproportionate fear of crime relative to its real occurrence. Yet even when there is evidence to the contrary, most elites still opt to build higher walls to guard themselves.”

Many of these shantytowns and townships were now no-go areas far beyond the reach of public security forces, he said.

“These areas are stigmatised by the public authorities and residents become quite literally trapped. Cities like Caracas, Nairobi, Port Harcourt and San Pedro Sula are giving rise to landscapes of … gated communities. Violence … is literally reshaping the built environment in the world’s fragile cities.”

Tuesday, 25 March 2014

Interview with Gail Tredwell

A former member of the inner circle of Amritanandamayi group, Gail Tredwell reveals what routinely happened in the camp during her time there.

Is she stating the truth?

Or

As the Amritanandamayi members state 'is she being manipulated' to malign the movement?

Probably, one needs a judicial enquiry to set the record state. But given the way the allegations against Satya Sai Baba were treated one's hopes are.....

Wednesday, 11 September 2013

The right to Offend

Pritish Nandy in The Times of India

Implicit in the freedoms we cherish in our democracy is our right to offend. (Editor - Is this so?) That is the cornerstone of all free thought and its expression. In a country as beautiful and complex as ours, it is our inalienable right to offend that makes us the nation we are. Of course I also recognise the fact that this right attaches to itself many risks, including the risk of being targeted. But as long as these risks are within reasonable, well defined limits, most people will take them in their stride. I am ready to defend my right to offend in any debate or a court of law. But it’s not fine when mobs come to lynch you. It’s not right, when they vandalise your home or burn your books or art or stop you from showing your film or, what’s becoming more frequent, hire thugs to kill you. Authors, journalists, painters, and now even activists and rationalists are being openly attacked and murdered.

It’s a constant challenge to walk the tightrope; to know exactly where to draw the line when you write, paint, speak.(Editor - Isn't this contradictory to the implicit right to offend statement at the introduction?) The funny thing is truth has no limits, no frontiers. When you want to say something you strongly believe in, there is no point where you can stop. The truth is always whole. When you draw a line, as discretion suggests, you encourage half truths and falsehoods being foisted on others, you subvert your conscience. In some cases it’s not even possible to draw a line. A campaigner against corruption can never stop midway through his campaign even though he knows exactly at which point the truth invites danger, extreme danger. Yet India is a brave nation and there are many common people, ordinary citizens with hardly any resources and no one to protect them who are ready to go out on a limb and say it as it is. They are the ones who keep our democracy burning bright.

Every few days you read about a journalist killed. About RTI activists murdered for exposing what is in the public interest. You read about people campaigning for a cause (like Narendra Dabholkar, who fought against superstitions, human sacrifices, babas and tantriks) being gunned down in cold blood. Even before the police can start investigations, the crime is invariably politicised. Issues of religion, caste, community, political affiliation are dragged in only to complicate (read obfuscate) the crime and, before you know it, the story dies because some other, even more ugly crime is committed somewhere else and draws away the headlines and your attention. And when that happens, criminals get away. We are today an attention deficit nation because there’s so much happening everywhere, all pretty awful stuff, that it’s impossible for anyone to stay focused.

Even fame and success can’t protect you. Dr Dabholkar was a renowned rationalist, a man of immaculate credentials. Yet he was gunned down by fanatics who thought he was endangering their trade in cheating poor and gullible people. Husain was our greatest living painter. He was forced into exile in his 80s because zealots refused to let him live and work in peace here. They vandalised his art; hunted down his shows, ransacked them. Yet Husain, as I knew him, was as ardent a Hindu as anyone else. His paintings on the Mahabharata are the stuff legends are made of. A pusillanimous Government lacked the will to intervene.

Another bunch of jerks made it impossible for Salman Rushdie to attend a litfest in Jaipur. Or go to Kolkata because Mamata Banerjee wanted to appease a certain section of her vote bank. For the same reason Taslima Nasreen was thrown out of Kolkata in 2007 by the CPM Government. Even local cartoonists in the state are today terrified to exercise their right to offend simply because Mamata has no sense of humour. Remember the young college girl on a TV show who asked her an inconvenient question? Remember how she reacted?

When we deny ourselves the right to offend, we deny ourselves the possibility of change. That’s how societies become brutal, moribund, disgustingly boring. Is this what you want? If the answer is No and you want to stay a free citizen, insist on your right to offend. If enough people do that, change is not just inevitable. It's assured. And change is what defines a living culture.

Implicit in the freedoms we cherish in our democracy is our right to offend. (Editor - Is this so?) That is the cornerstone of all free thought and its expression. In a country as beautiful and complex as ours, it is our inalienable right to offend that makes us the nation we are. Of course I also recognise the fact that this right attaches to itself many risks, including the risk of being targeted. But as long as these risks are within reasonable, well defined limits, most people will take them in their stride. I am ready to defend my right to offend in any debate or a court of law. But it’s not fine when mobs come to lynch you. It’s not right, when they vandalise your home or burn your books or art or stop you from showing your film or, what’s becoming more frequent, hire thugs to kill you. Authors, journalists, painters, and now even activists and rationalists are being openly attacked and murdered.

It’s a constant challenge to walk the tightrope; to know exactly where to draw the line when you write, paint, speak.(Editor - Isn't this contradictory to the implicit right to offend statement at the introduction?) The funny thing is truth has no limits, no frontiers. When you want to say something you strongly believe in, there is no point where you can stop. The truth is always whole. When you draw a line, as discretion suggests, you encourage half truths and falsehoods being foisted on others, you subvert your conscience. In some cases it’s not even possible to draw a line. A campaigner against corruption can never stop midway through his campaign even though he knows exactly at which point the truth invites danger, extreme danger. Yet India is a brave nation and there are many common people, ordinary citizens with hardly any resources and no one to protect them who are ready to go out on a limb and say it as it is. They are the ones who keep our democracy burning bright.

Every few days you read about a journalist killed. About RTI activists murdered for exposing what is in the public interest. You read about people campaigning for a cause (like Narendra Dabholkar, who fought against superstitions, human sacrifices, babas and tantriks) being gunned down in cold blood. Even before the police can start investigations, the crime is invariably politicised. Issues of religion, caste, community, political affiliation are dragged in only to complicate (read obfuscate) the crime and, before you know it, the story dies because some other, even more ugly crime is committed somewhere else and draws away the headlines and your attention. And when that happens, criminals get away. We are today an attention deficit nation because there’s so much happening everywhere, all pretty awful stuff, that it’s impossible for anyone to stay focused.

Even fame and success can’t protect you. Dr Dabholkar was a renowned rationalist, a man of immaculate credentials. Yet he was gunned down by fanatics who thought he was endangering their trade in cheating poor and gullible people. Husain was our greatest living painter. He was forced into exile in his 80s because zealots refused to let him live and work in peace here. They vandalised his art; hunted down his shows, ransacked them. Yet Husain, as I knew him, was as ardent a Hindu as anyone else. His paintings on the Mahabharata are the stuff legends are made of. A pusillanimous Government lacked the will to intervene.

Another bunch of jerks made it impossible for Salman Rushdie to attend a litfest in Jaipur. Or go to Kolkata because Mamata Banerjee wanted to appease a certain section of her vote bank. For the same reason Taslima Nasreen was thrown out of Kolkata in 2007 by the CPM Government. Even local cartoonists in the state are today terrified to exercise their right to offend simply because Mamata has no sense of humour. Remember the young college girl on a TV show who asked her an inconvenient question? Remember how she reacted?

When we deny ourselves the right to offend, we deny ourselves the possibility of change. That’s how societies become brutal, moribund, disgustingly boring. Is this what you want? If the answer is No and you want to stay a free citizen, insist on your right to offend. If enough people do that, change is not just inevitable. It's assured. And change is what defines a living culture.

Tuesday, 3 September 2013

The political overlords of a violent underclass

THE HINDU

Skewed growth is pushing the marginalised into the arms of waiting netas who turn them into tools of violence

The rape of a photojournalist in midtown Mumbai has revived public indignation and the debate that followed the brutal and barbaric rape of a young Delhi girl in December 2012. Amidst much hand-wringing and a rerun of inanities over national television, talking heads seem to have once again missed the central narrative — the rising tide of assorted violent acts, the political patronage (both explicit and implicit) that’s sponsoring it and how rape might be an integral part of this hostile environment. What’s more, the horrific incidents of rape continue unabated.

As India staggers from a semi-feudal society to one that’s embracing a strange (and hybrid) version of capitalism, violence in its myriad forms has emerged as the dominant template. The repertoire of violence has graduated from booth-capturing during elections to assassinating political opponents (including whistle-blowers), from vandalising art shows to rape and murder. And the culprits seem to be getting away each time. While the government continues to attract a large share of public censure for its inaction, the blame should ideally lie with the entire political class. It is this section of society, and the trajectory of its evolution, which seems to be strengthening the foundations of violence in our society. Every political party today — across all aisles and the entire spectrum — has to maintain a large army of warm bodies, described variously as “lumpen proletariats,” or “lumpens” or “the underclass,” for implementing its dirty tricks.

In simple terms, these are people thought to inhabit the space below the working class. Social scientists use the term to describe anybody who lives outside the pale of the formal wage-labour system. Disenfranchised and conventionally unemployable, political parties use these people to commit acts — most of which are outright criminal — to improve its own popularity and election prospects.

Becoming invincible

When utilised by political parties as the blunt edge of a bludgeon, this section of society acquires a modicum of invincibility. Given the large-scale subversion of the police force by politicians, lumpens have acquired a sense of daredevilry, a brazen approach to law and order. Immunity from arrests and indifference towards due process of law has invested them with a special feeling of invulnerability.

Some of this imperviousness is inevitable as criminals, or individuals with criminal accusations, become elected representatives themselves. This is a disease that afflicts all political parties. According to the Association for Democratic Reforms, 1,448 of India’s 4,835 MPs and State legislators have declared criminal cases against them. In fact, 641 of these 1,448 are facing serious charges like murder, rape and kidnapping.

The violence is also reflective of the pushing and jostling for elusive entitlements, a handmaiden of the stop-go model of development pursued by India. Asynchronous development of the economy and its institutions often lead to the privileged sections of society cornering disproportionate gains, resulting in discontent among the less fortunate. This then becomes a fertile hunting ground for political dividends. As the economy staggers through a new model of development without overhauling the outdated feudal structure — that still discriminates on the basis of caste, sex, class — missed opportunities and unrealised aspirations push many of the deprived into the arms of opportunist politicians.

Divested of education and employment opportunities, bereft of basic health facilities, exploited by the powerful and ignored by society, the underclass can only turn to political warlords for not only survival but to also actualise their dreams and aspirations. They become the shadow army, the heaving underbelly that the urban middle class doesn’t want to talk about.

Writing in the newspaper Business Standard, T.N. Ninan described the men behind the Delhi rape: “The men who raped and killed...have biographies that are starkly different. Their families may not have been from backgrounds vastly different from that of the girl’s father; they too were mostly one generation removed from villages in North Indian states. But they fell through the cracks in the Indian system — cracks that are so large that they are the system itself.”

To be sure, the combination of economic prosperity for a select few and abject poverty for large sections of the population is a guaranteed recipe for social combustion. When privilege, or nepotism, determines access to scarce resources, conflict is bound to erupt. Inequality, of any kind, remains the spring-well for all conflicts.

Violence is also a way of ensuring maintenance of this privilege. On the day of the Mumbai rape incident, a Shiv Sena MLA abused and threatened women employees of a toll booth in Maharashtra. About a fortnight ago, Shiv Sena and Maharashtra Navnirman Sena party workers beat up North Indian migrant workers in Kolhapur at random as a protest against the rape of a five-year-old allegedly by a labourer from Jharkhand. Not very long ago, a fringe, religio-political outfit in Mangalore, Karnataka, used the excuse of moral offence to inflict violence against young boys and girls. A senior police officer in Uttar Pradesh was shot dead — allegedly by associates of a local politician — when investigating a land dispute.

Police reforms

If these examples of violence seem random and arbitrary, here is the simple truth: if you can dream up any imaginary offence against any section of society, contemporary Indian political grammar gives you the licence to inflict violence against that segment. In the meantime, certain law officers and do-gooders wanting to eradicate rape and sexual crimes from society seem intent on examining the wrong end of a telescope: they are contemplating a ban on pornography.

What’s even more unfortunate is that the police look on helplessly, since their career progression is tied closely to the moods of political masters orchestrating these unorganised armies. Sometimes, they refuse to act even against political goons out of power because who knows what hand will be dealt during the next election.

There have been numerous suggestions and various committee reports on how to reform the police force. The Supreme Court in 2006 had also suggested seven measures to improve the police force. But like all other tough decisions, the government swept this too under the carpet. In addition, lack of proper investigation and poor documentation by the police often forces the judiciary to put criminals back on the streets even before you can say Amar-Akbar-Anthony. As a result, the fear of law ceases to exist.

Growing intolerance

Another form of violent behaviour is now finding sanction from political parties across ideological divides — a new-found love for banning painters, authors, film-makers, etc. Political parties find justifications for banning any art form, using hired goons — who have perhaps never been acquainted with the contentious piece of work — to vandalise and wreak havoc. Recently, supporters of a right wing party vandalised an art show in Ahmedabad for exhibiting works of Pakistani artists. A political party has to only utter indignant statements about any creative work and a ban is immediately enforced. Canada-based, Indian-born writer Rohinton Mistry’s award winning book Such a Long Journey was hurriedly removed from Mumbai University’s syllabus after similar protests. Violence takes many forms and unfortunately India has become home to most of these varieties: imported terrorism, domestic violence, female foeticide, armed insurgency, criminal activity, communal acts, oppression (of caste or gender), etc. While politics does have an indirect role in promoting domestic violence or some criminal activities, its fingerprints are all too visible in all the other forms of violence perpetrated in the country. It’s surprising that a country which gained independence from colonial powers through the instrument of non-violence should today exhibit such a preponderance of violence in its daily life.

But what is baffling is how, increasingly, rape is committed without any fear of legal reprisal or the extent of punishment that might be meted out. Sample the West Bengal government’s reluctance to prosecute party workers accused of rape. It is therefore not surprising that increasing incidents of mindless violence and sexual assaults are being reported from across the country. Judicial commissions and committees are slowly drawing attention to this aberrant social phenomenon: political sanction for violence.

Verma report

The Justice Verma Committee castigates the political class in its report for pandering to chauvinistic and patently anti-women organisations (such as khap panchayats). The committee also pans the political class for ignoring the rights of women since Independence: “Have we seen an express denunciation by Parliament to deal with offences against women? Have we seen the political establishment ever discuss the rights of women and particularly access of women to education and such other issues over the last 60 years in Parliament? We find that over the last 60 years the space and the quantum of debates which have taken place in Parliament in respect of women’s welfare has been extremely inadequate.”

A licence to kill should ideally live only in fiction. A free hand to maim or murder has created a fascist mindset, a mental construct that is at odds with the aspirations of an ancient civilisation trying to find a place on the high table of the modern, free world. It is often argued that the first step in evolving sustainable solutions probably lies in creating independent institutions. But, that might not be enough. As Nobel Prize winning economist and philosopher Amartya Sen has said in his book The Idea of Justice, the existence of democratic institutions is no guarantee of success. “It depends inescapably on our actual behaviour patterns and the working of political and social interactions.”

The first step then might be to provide everybody with equal opportunity — access to education, employment, health care, basic infrastructure (like water or power) — and to overhaul the political system itself by reforming campaign finance.

Friday, 2 August 2013

Uruguay - the first country to create a legal market for drugs

Uruguay has taken a momentous step towards becoming the first country in the world to create a legal, national market for cannabis after the lower chamber of its Congress voted in favour of the groundbreaking plan.

The Bill would allow consumers to either grow up to six plants at home or buy up to 40g per month of the soft drug – produced by the government – from licensed chemists for recreational or medical use. Previously, although possession of small amounts for personal consumption was not criminalised in the small South American nation, growing and selling it was against the law.

The Bill passed by 50 votes to 46 shortly before midnight on Wednesday after a 14-hour debate as pro-legalisation activists crowded the balconies above the legislature floor.

Uruguay’s Senate, where the ruling left-wing coalition has a larger majority, is now expected to approve the measure. President José Mujica, an octogenarian former armed rebel – who has previously overseen the passing of measures to allow abortion and gay marriage – backs the move.

Proponents of the Bill argue marijuana use is already prevalent in Uruguay and that by bringing consumers out of the shadows the government will be better able to regulate their behaviour, drive a wedge between them and peddlers of harder, more dangerous drugs, and tax cannabis sales.

They also believe that it closes the loophole that outlaws growing or buying cannabis while turning a legal blind eye to its consumption. Currently, judges in Uruguay have discretion to decide whether an undefined small quantity of the drug is for personal use or not.

Campaigners for an end to prohibition were quick to claim the vote as a landmark in the international push for drug policy reform. “Sometimes small countries do great things,” said Ethan Nadelmann, executive director of the New York-based Drug Policy Alliance, whose board includes entrepreneur Richard Branson, but also the late President Ronald Reagan’s former Secretary of State, George Shultz.

“Uruguay’s bold move does more than follow in the footsteps of Colorado and Washington,” added Mr Nadelmann, referring to the two Western US states that recently also permitted recreational cannabis use. “It provides a model for legally regulating marijuana that other countries, and US states, will want to consider.”

Hannah Hetzer, the Drug Policy Alliance’s Americas coordinator, who is based in Montevideo, added: “At the heart of the Uruguayan marijuana regulation Bill is a focus on improving public health and public safety. Instead of closing their eyes to the problem of drug abuse and drug trafficking, Uruguay is taking an important step towards responsible regulation of an existing reality.”

Nevertheless, the measure has divided Uruguay and in the run-up to the vote few dared predict its outcome, with the 99-member house almost split down the middle. All 49 opposition deputies had agreed to vote against the measure en bloc, while the 50 members of President Mujica’s ruling coalition were due to back it.

One of the government deputies, Darío Pérez, a doctor by training, had warned that cannabis is a gateway drug to harder substances and feared that fully legalising it would trigger a mushrooming of Uruguay’s already serious problems with crack and other cheaper, highly addictive cocaine derivatives.

In the most keenly awaited speech of the debate, Mr Pérez attacked the Bill but said he would vote in line with the coalition whip, although he could not have made his displeasure clearer. “Marijuana is manure,” he told the chamber. “With or without this law, it is the enemy of the student and of the worker.”

Mr Pérez was also unhappy with what he saw as a broken promise by Mr Mujica not to foist the law on a society that was not yet ready for it, citing a recent survey by pollsters Cifra that found 63 per cent of Uruguayans opposed cannabis legalisation while 23 per cent backed it.

Last December, the president had temporarily placed the measure on the back burner to give advocates a chance to rally public opinion. “The majority has to come in the streets,” he said then. “The people need to understand that with bullets and baton blows, putting people in jail, the only thing we are doing is gifting a market to the narco-traffickers.”

But those arguments failed to convince Gerardo Amarilla, a deputy for the conservative opposition National Party, who told the chamber: “We are playing with fire. Maybe we think that this is a way to change reality. Unfortunately, we are discovering a worse reality.”

Official studies from Uruguay’s National Drugs Board have found that of the country’s population of 3.4 million, around 184,000 people have smoked cannabis in the last year. Of that number, 18,400 are daily consumers. But independent researchers believe that may be a serious underestimate. The Association of Cannabis Studies has claimed there are 200,000 regular users in Uruguay.

One thing that no one disputes is that Uruguay has a serious and growing problem with harder drugs, principally cocaine and its highly addictive derivatives flooding into the Southern Cone and Brazil, mainly from Peru and Bolivia. That, in turn, has fuelled a crime wave as addicts seek to fund their cravings. Breaking the link between them and cannabis users is one of the government’s principal justifications for marijuana legalisation.

Under the measure, registered users will be able to buy cannabis from the nation’s chemists, cultivate plants at home and form cannabis clubs of 15 to 45 members to collectively grow up to 99 plants. Although the high would depend on the strength of the cannabis, which can vary significantly, the 40g per month limit would allow a user to potentially smoke several joints every day. To prevent cannabis tourism, such as that which has developed in Amsterdam, only Uruguayan nationals will be able to register as cannabis purchasers or growers.

Uruguay’s move comes as pressure grows across Latin America for a new approach to Washington’s “war on drugs”, which has ravaged the region, seeing hundreds of thousands die in drug-fuelled conflicts from Brazil’s favelas to Mexico’s troubled border cities.

Colombia President Juan Manuel Santos has called for a discussion of the alternatives while his Guatemalan counterpart Otto Pérez Molina has openly advocated legalisation. Meanwhile, Felipe Calderón, President of Mexico from 2006 to 2012, has also called for a look at “market” solutions to the drug trade.

Crucially, all three are conservatives with impeccable records as tough opponents of the drug trade. Mr Pérez Molina is a former army general with a no-nonsense reputation, while Mr Santos served as Defence Minister for his predecessor, the hard-right President Álvaro Uribe. Meanwhile, Mr Calderón was widely criticised during his time in power for the bloodbath unleashed by his full-frontal assault on the drug cartels, a conflict which cost an estimated 60,000 lives during his presidency.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)