'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label exodus. Show all posts

Showing posts with label exodus. Show all posts

Tuesday, 18 April 2023

Wednesday, 23 March 2022

Sunday, 2 November 2014

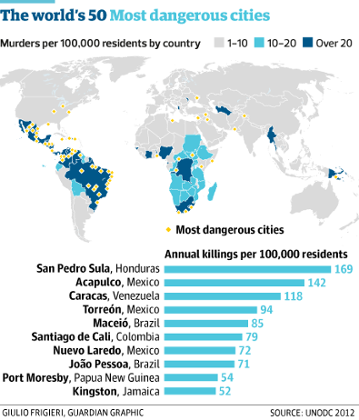

Murder capitals of the world: how runaway urban growth fuels violence

San Pedro Sula, Honduras, is the most dangerous city on the planet – and experts say it is a sign of a global epidemic

- John Vidal, environment editor

- The Observer,

It was relatively quiet in San Pedro Sula last month. A gunfight between police and a drug gang left a 15-year-old boy dead; the body of a man riddled with bullets was found in a banana plantation; two lawyers were gunned down; a salesman was murdered inside his 4x4; and a father and son were murdered at home after pleading not to be killed.

----Also read

----Also read

Humanity's 'inexorable' population growth is so rapid that even a global catastrophe wouldn't stop it

-----

One politician survived an assassination attempt and around a dozen people were found dead in the street. The number of killings is said to have fallen in the last few months, but the Honduran city is officially the most violent in the world outside the Middle East and warzones, with more than 1,200 killings in a year, according to statistics for 2011 and 2012. Its murder rate of 169 per 100,000 people far surpasses anything in North America or much larger cities such as Johannesburg, Lagos or São Paulo. London, by contrast, has just 1.3 murders per 100,000 people.

Now research by security and development groups suggests that the violence plaguing San Pedro Sula – a city of just over a million, and Honduras’s second largest – and many other Latin American and African cities may be linked not just to the drug trade, extortion and illegal migration, but to the breakneck speed at which urban areas have grown in the last 20 years.

The faster cities grow, the more likely it is that the civic authorities will lose control and armed gangs will take over urban organisation, says Robert Muggah, research director at the Igarapé Institute in Brazil.

“Like the fragile state, the fragile city has arrived. The speed and acceleration of unregulated urbanisation is now the major factor in urban violence. A rapid influx of people overwhelms the public response,” he adds. “Urbanisation has a disorganising effect and creates spaces for violence to flourish,” he writes in a new essay in the journal Environment and Urbanization.

Muggah predicts that similar violence will inevitably spread to hundreds of other “fragile” cities now burgeoning in the developing world. Some, he argues, are already experiencing epidemic rates of violence. “Runaway growth makes them suffer levels of civic violence on a par with war-torn [cities such as] Juba, Mogadishu and Damascus,” he writes. “Places like Ciudad Juárez, Medellín and Port au Prince … are becoming synonymous with a new kind of fragility with severe humanitarian implications.”

Simon Reid-Henry, of the Peace Research Institute in Oslo, said: “Today’s wars are more likely to be civil wars and conflict is increasingly likely to be urban. Criminal violence and armed conflict are increasingly hard to distinguish from one another in different parts of the world.”

The latest UN data shows that many cities may be as dangerous as war zones. While nearly 60,000 people die in wars every year, an estimated 480,000 are killed, mostly by guns, in cities. This suggests that humanitarian groups, which have traditionally focused on working in war zones, may need to change their priorities, argues Kevin Savage, a former researcher with the Overseas Development Institute in London.

“Some urban zones are fast becoming new territories of conflict and violence. Chronically violent cities like Abidjan, Baghdad, Kingston, Nablus, Grozny and Mogadishu are all synonyms for a new kind of armed conflict,” he said. “These urban centres are experiencing a variation of warfare, often in densely populated slums and shantytowns. All of them feature pitched battles between state and non-state armed groups and among armed groups themselves.”

European and North American cities, which mostly grew over 150 or more years, are thought unlikely to physically expand much in the next few decades and are likely to remain relatively safe; but urban violence is certain to worsen as African, Asian and Latin American cities swell with population growth and an unprecedented number of people move in from rural areas.

More than half the world now lives in cities compared with about 5% a century ago, and UN experts expect more than 70% of the world’s population to be living in urban areas within 30 years.

The fastest transition to cities is now occurring in Asia, where the number of city dwellers is expected to double by 2030, according to the UN Population Fund. Africa is expected to add 440 million people to its cities by then and Latin America and the Caribbean nearly 200 million. Rural populations are expected to decrease worldwide by 28 million people. Most urban growth is expected to be not in the world’s mega-cities of more than 10 million people, but in smaller cities like San Pedro Sula.

“We can expect no slowing down of urbanisation over the next 30 years. The youth bulge will go on and 90% of the growth will happen in the south,” said Muggah.

But he and other researchers have found that urban violence is not linked to poverty so much as inequality and impunity from the law – both of which may encourage lawlessness. “Many places are poor, but not violent. Some favelas in Brazil are among the safest places,” he said. “Slums are often far less dangerous than believed. There is often a disproportionate fear of crime relative to its real occurrence. Yet even when there is evidence to the contrary, most elites still opt to build higher walls to guard themselves.”

Many of these shantytowns and townships were now no-go areas far beyond the reach of public security forces, he said.

“These areas are stigmatised by the public authorities and residents become quite literally trapped. Cities like Caracas, Nairobi, Port Harcourt and San Pedro Sula are giving rise to landscapes of … gated communities. Violence … is literally reshaping the built environment in the world’s fragile cities.”

Saturday, 21 September 2013

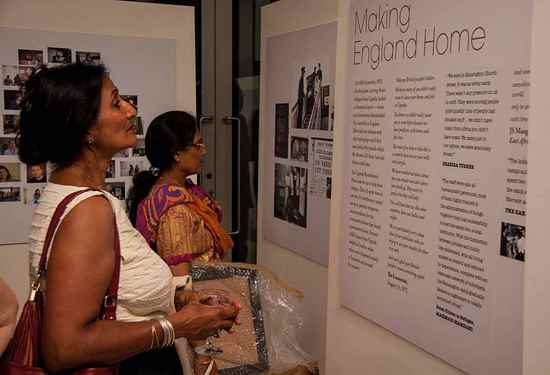

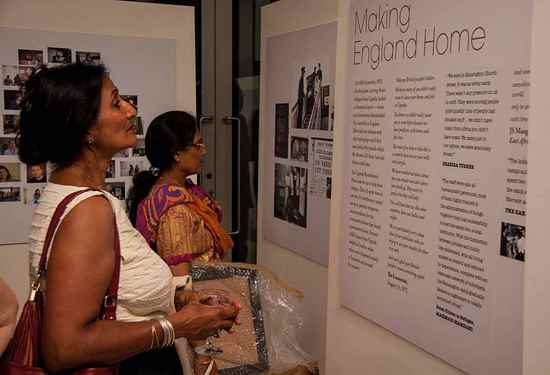

The story of exiled Ugandan Indians in the UK

It’s not over Ugandan Indians landing in London, 1972

LONDON: EXHIBITION

Goodbye Africa

There is an apocryphal story about an American tourist who, upon arrival in London, was greeted by a friendly taxi driver called Patel; then discovers that the hotel he was booked in was run by a Patel; the corner store was owned by a Patel; the pharmacy next door was managed by a Patel; and the money-changer across the road was a Patel. After he goes to a restaurant and realises half the staff was Patel, he shakes his head in disbelief and jokes: “Is the blooming queen a Patel too?”

That American tourist would probably have loved to see ‘Exiles: the Ugandan Asian Story’, an exhibition tracing the roots of Britain’s Ugandan Indians (the Patels, Shahs and Amins) who settled here after being expelled by Idi Amin in 1972, sparking one of the biggest waves of migration of Asians from east Africa.

Forty years later, they are a thriving community with a foot in every door and the biggest immigrant success story.(Editor's note - Similar to the Sindhis in post independence India.) But, as the exhibition tells us through personal testimonies, photographs, letters, newspaper reports and TV footage, it could have had a very different ending but for the sheer tenacity and enterprise of a people who, despite having lost everything, refused to accept defeat.

Being suddenly uprooted from their homeland and forced to make a home in an alien, cold, rain-sodden country was a traumatic experience. And memories of that nightmare still haunt them. Many retain vivid recollections of the day, August 4, 1972, that was to change their lives forever following Idi Amin’s dramatic radio broadcast: “I had a dream that if I expel all Asians with whatever passports they are holding, take away all their businesses, Uganda will prosper.”

Kirit Thakkar was 17 at the time. “It was two in the afternoon. I had come home from school and we had just finished our lunch when we heard it on the radio. It was a big shock...what would happen to our extended family? What would happen to the businesses we had built over the last 40-50 years? Apart from Uganda, we did not know any other country where we could make a permanent base for ourselves,” he says in a podcast recorded by the National Archives to mark the 40th anniversary of Amin’s expulsion of some 70,000 Indian-origin Asians.

That American tourist would probably have loved to see ‘Exiles: the Ugandan Asian Story’, an exhibition tracing the roots of Britain’s Ugandan Indians (the Patels, Shahs and Amins) who settled here after being expelled by Idi Amin in 1972, sparking one of the biggest waves of migration of Asians from east Africa.

Forty years later, they are a thriving community with a foot in every door and the biggest immigrant success story.(Editor's note - Similar to the Sindhis in post independence India.) But, as the exhibition tells us through personal testimonies, photographs, letters, newspaper reports and TV footage, it could have had a very different ending but for the sheer tenacity and enterprise of a people who, despite having lost everything, refused to accept defeat.

Being suddenly uprooted from their homeland and forced to make a home in an alien, cold, rain-sodden country was a traumatic experience. And memories of that nightmare still haunt them. Many retain vivid recollections of the day, August 4, 1972, that was to change their lives forever following Idi Amin’s dramatic radio broadcast: “I had a dream that if I expel all Asians with whatever passports they are holding, take away all their businesses, Uganda will prosper.”

Kirit Thakkar was 17 at the time. “It was two in the afternoon. I had come home from school and we had just finished our lunch when we heard it on the radio. It was a big shock...what would happen to our extended family? What would happen to the businesses we had built over the last 40-50 years? Apart from Uganda, we did not know any other country where we could make a permanent base for ourselves,” he says in a podcast recorded by the National Archives to mark the 40th anniversary of Amin’s expulsion of some 70,000 Indian-origin Asians.

|

An estimated 28,000 arrived in Britain, most with virtually nothing except the clothes on their bodies. They were given just 90 days to pack up and leave, and allowed to take the equivalent of only £50 out of the country. “You can call it a riches-to-rags story,” says Jyoti Patel, who was 13 when her world suddenly turned upside down. Her father was a well-to-do businessman, but had to leave everything behind. “We came with nothing. It was a cold, freezing night when we landed here. Most of us didn’t have warm clothes or even proper footwear. We came in chappals,” she told Outlook. They were put up in disused military barracks which had been converted into refugee camps. Many could not speak English, so it was hard to get around. “It was quite a culture shock. Everything was new. We had never eaten cornflakes before and didn’t know you were supposed to mix it with milk!” she says, recounting the initial adjustment process.

It took them some time to find their bearings, but once they did, there was no looking back. Soon, many of them gave up jobs to set up their own businesses. They bought homes, built temples and started their own newspapers, laying the foundations of a successful close-knit community which today is the envy of other immigrant groups. Many Ugandan Asians see the exodus as a blessing in disguise. An old lady thrown out by Amin in 1972 is said to have preserved a photograph of him as a mark of “gratitude”.

The exhibition is the culmination of the Council of Asian People’s year-long Exiles project. “It’s the story of ordinary people who experienced extraordinary trauma before starting a new life in the UK. It is a story that needs to be told before memories are lost forever,” says project coordinator Jayesh Amin.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)