It is reported that when the 6th Duke of Westminster, who died this week, realised at the age of 15 that he was heir to his family’s immense fortune, he dreaded it – the responsibility, the knowledge that he hadn’t earned it, the isolation it would bring him. He would have prepared his son for the eventuality of becoming duke, although neither would have wanted to think it would happen as early as it did. On Tuesday, Gerald Grosvenor died suddenly at the age of 64; his son Hugh, now the 7th Duke of Westminster, is just 25 and inherits the family’s £9.3bn fortune.

Aside from the trauma of losing a parent – having money does not ease the pain of bereavement – the 25-year-old finds himself in both an enviable, and unenviable, position. On the one hand, he becomes one of the richest men in the world; on the other, money didn’t bring happiness to his father, who appeared to find his title and wealth a burden. “Given the choice I would rather not have been born wealthy, but I never think of giving it up,” he said once. “I can’t sell it. It doesn’t belong to me.”

The Duke of Westminster

It is, however, very difficult to feel sorry for the rich, which is, in itself, a problem for many of them. “They know that others have no sympathy for them, and no understanding of the situation they’re in,” says Thayer Willis, author of Navigating the Dark Side of Wealth: A Life Guide for Inheritors, who runs a counselling business helping the rich deal with the psychological challenges of wealth. “They know not to go around whining and expecting people to feel sorry for them.”

But there are serious challenges that come from inheriting vast fortunes, she says, particularly at a young age. Willis knows many of them herself – she was born into the family that started the Georgia-Pacific Corporation, a timber company worth billions. “I stumbled through my 20s and made a lot of mistakes,” she says.

“For all of us, our 20s and 30s are the ‘building years’, when we’re meant to get out in the world, figure out who we are, what we like to do, who we like, who we like to date,” she says. “Having a tremendous amount of financial wealth come into your life at that point really messes with motivation. All of a sudden the question becomes: ‘What do I need to do to manage this wealth?’ instead of: ‘How do I identify and clarify who I really am?’ People’s motivation to be around you becomes questionable. Are they attracted to me or to this wealth?” These are “definitely first-world problems, but it certainly messes with the psychological development of that young adult”. In her 30s, Willis settled down, trained as a psychotherapist and became a wealth counsellor.

If it’s so awful – an obvious question – why not give the money away? “Some people think of that, usually to the horror of the family. Older family members understand what this money can do in terms of providing a resource for any kind of emergency, or starting a business, or philanthropy.”

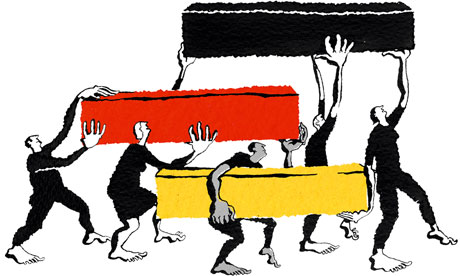

For inheritors of wealth going back generations, there is a sense, as Grosvenor said, that they are mere custodians and the money isn’t theirs to give away or lose. “I’ve seen some quite young heirs who really understand the dynastic vision of a family from a pretty early age,” says Julian Washington, head of intermediary relationship management at RBC Wealth Management. “They don’t want to be the weak link in the chain when the family story is told. In my experience, when you deal with old-money families, if you want to call them that, they tend to be pretty good at educating their next generation, because typically they’ve been doing it for centuries.” And when someone – a male member of the family, thanks to outrageous primogeniture – comes to inherit, “more often than not they’re in a pretty good place because they come to it with all that tradition and they understand the nature of the shoes they’re stepping into”.

Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan Zuckerberg have decided to give away 99% of their fortune – but their daughter, Max, could still inherit $450m. Photograph: AP

Plenty of members of the super-rich have already decided not to burden their children with vast, unearned fortunes in the first place – it is enough that they have had expensive educations and all the opportunities of a privileged start in life. Warren Buffett’s famous take on inheritance is to leave his children “enough money so that they would feel they could do anything, but not so much that they could do nothing”. It has been reported, though not confirmed, that Bill Gates plans to leave his children a meagre $10m (£7.7m) each from his $76bn fortune. Mark and Priscilla Zuckerberg have pledged to give away 99% of their $45bn pile(although it’s all relative – this still leaves them, and their daughter, with $450m). Not quite on the same financial scale, Nigella Lawson has said she isn’t planning to leave her children anything: “It ruins people not having to earn money.”

Sam Roddick, the daughter of the Body Shop founder Anita Roddick, didn’t know that her mother, who died in 2007, had planned to give away her entire £51m fortune. “We found out when it was published in a Daily Mail article,” she laughs. It wasn’t entirely a surprise – her parents were socialists, rather than socialites, and their business was famous for its fair-trade principles. And it wasn’t personal. Cutting one’s child out of your will can, to some, seem like “a deep act of abandonment. I never had that abandonment because I had a healthy relationship with her. I know other people who haven’t been given money and it has been a huge act of aggression.”

Duke's £9bn inheritance prompts call for tax overhaul

Roddick was also unusual among the children of the rich in that she hadn’t grown up surrounded by wealth. She was largely brought up by her working-class grandmother, “and working-class values – you work hard, you earn your keep and you contribute to society. Entitled people from inherited wealth are all about other people being in service to them.”

She has observed the very wealthy people she has met over the years. “They are isolated from normal society,” she says. With the extremely wealthy, “relationships become transactional, and that is something that is extraordinarily emotionally damaging. A lot of very wealthy people are not accountable to their community, they’re not accountable to the people they love, they show their power and control through transaction and they are unhappy, from what I can tell. The people I know who are very wealthy and are happy are all contributing something to society.” Until we sort out the rules that allow vast fortunes held in trusts, as the Grosvenor estate is, to avoid hefty death duties and be passed down the generations, it’s something for the new Duke of Westminster and his future male heirs to bear in mind.