If the FT's attack on the radical economist's 'rising inequality' thesis is right, then all the gross designer bling in its How To Spend It section can be morally justified

The adverts in the FT and other reputable papers – mainly for large watches, first-class air travel, portable fine art etc – should be collectively retitled How To Hide It

Thomas Piketty's Capital was still No 3 on the Amazon bestseller list when the Financial Times dropped its front-page bombshell. By picking through the spreadsheets the "rock-star French economist" had placed online, the FT concluded that his key data appeared to be "constructed out of thin air".

Piketty's claim that inequality in the west has risen since the 1970s is wrong, says the FT's Chris Giles. And on this basis, Piketty's view that rising inequality is the central contradiction of capitalism, and will get worse, is also wrong.

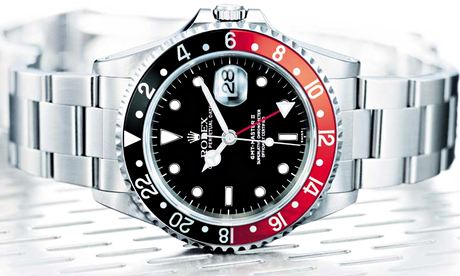

It is always right to trawl through data. There is so much grossing and smoothing in economics, and so little of the realtime peer review that happens in science, that data should always be challengable. But the gleeful response to Piketty's "errors" on the rightwing Twittersphere did not happen because some FT pointy-heads discovered a few fat-finger inputs. It happened because, if Giles is right, then all the gross designer bling advertised in the FT's How To Spend It can be morally justified: it is evidence of rising social wealth in general, not the excess of a few Rolex types.

But the attack does not quite come off. For Sweden and France, the FT's conclusions barely diverge from Piketty's. For Britain and the US they do: the official figures capture the general curve of inequality downwards in the mid-20th century, but shatter into incoherence after 1970, failing to match Piketty's claim that wealth inequalities have increased.

There is an obvious reason for this: since time immemorial the rich have been averse to declaring their wealth. But after 1979 capitalism was restructured to promote wealth accumulation, ending the "euthanasia of the rentier" Keynes had designed into the postwar system.

Unlike income, which has been vigorously taxed since the mid-19th century and therefore recorded, personal wealth was, after 1979, the subject of a half-hearted cat-and-mouse game in which the cat and the mouse were wont to share yachting trips to the Aegean on a regular basis. That's why the work of Piketty and his collaborators had to be based on a mixture of inheritance tax data and surveys, plus a large amount of calculation.

Piketty's figures show a clear upward trend to inequality in the UK since the 70s; the FT's preferred official data dissolves into a series of squiggles that show nothing conclusive. And let's be clear why: the HMRC currently estimates that the top 10% of the population own 70% of the wealth, while the Office for National Statistics thinks they own just 44%. The discrepancy occurs because, of course, there is neither requirement nor desire to record actual market wealth at all. There are only inheritance tax returns on estates big enough to pay it.

The old Inland Revenue figures for UK wealth were so wonky that they abandoned efforts to calculate them: but in their last attempt (2005) they said that on top of £3.4tn "identified" wealth in the UK, a further £1.7tn had to be assumed that was either not declared or belonged to people who slipped through the net.

For this reason one of Piketty's key demands is the automatic sharing of bank information between states and banks. The principle is simple, he writes: "National tax authorities should receive all the information they need to calculate the net wealth of every citizen." Why that might be needed is understood if you flick through the wealth management magazines produced by the FT and other reputable papers. The adverts – mainly for large watches, first-class air travel, portable fine art, tax haven accountants and capacious luggage – deliver a clear subliminal message. They should be collectively retitled "How To Hide It".

In the end, Piketty did not claim there had been a vast increase in wealth disparities since the 1970s. Piketty's prediction is that the moderate rise in inequality under neoliberalism is set to gather pace in the 21st century, taking us back to Victorian levels by 2050. His prediction is based on simple maths: if growth is low, and the bargaining power of labour low, and the returns on capital high, then it is more logical to sit on assets and speculate rather than accumulate wealth by work, invention or entrepreneurial risk.

Piketty asks the question that mainstream economics doesn't want to answer: do we want a society based on work and ingenuity or on rent?

It's not an academic question. Figures from Lloyds Private Bank show UK asset wealth grew from £4.7tn to £7.8tn in the decade to 2013, with most of that generated by the rising value of financial portfolios, and all wealth growing faster than incomes and inflation. If Piketty's figures are wrong, the probable cause – beyond the odd transcription error – is a mild overestimation of a clear trend, generated in an attempt to uncover modern capitalism's guilty secret. If the FT's figures are wrong, it is because they rely on those of governments that have become – as Peter Mandelson once put it – "intensely relaxed about people becoming filthy rich".

But the most important question is the future: if Piketty is right then we have to "euthanase" the rentier class all over again. Only taxes on current wealth – and an end to opaque "wealth management" trails that end up in Switzerland or Cyprus – will prevent capitalism generating levels of social inequality that destroy it.

Paul Mason is economics editor at Channel 4 News and the author of Why It's Kicking Off Everywhere.