Adam Vaughan in The Guardian

A wave of new publicly owned companies is taking on the big six energy suppliers, as local authorities search out new revenue and seek to restore faith in public services and tackle fuel poverty.

Islington council last week launched a not-for-profit energy firm, London’s first municipal operator in more than a century, while Doncaster’s energy company will start early next month.

Portsmouth is also on the verge of becoming the first Conservative-controlled council to launch one, to bring down residents’ bills as well as bringing investment to the city.

The first and best-known publicly owned energy companies, Robin Hood Energy in Nottingham and Bristol Energy, started two years ago. But the growing trend came to the fore this month when Nicola Sturgeon promised to create a Scottish public energy company by 2021.

“No shareholders to worry about. No corporate bonuses to consider. It would give people – particularly those on low incomes – more choice and the option of a supplier whose only job is to secure the lowest price for consumers,” Scotland’s first minister said, in an echo of the marketing used by the councils who have already started their own energy companies.

Sturgeon’s firm will be entering an increasingly crowded space: publicly owned firms include Liverpool’s Leccy, Derby’s Ram, and Leeds’ White Rose. Councils in Sussex are clubbing together to launch Your Energy Sussex latter this year.

The driving forces for these councils stepping into the complex, heavily regulated energy space are largely twofold. One is the need to create a new revenue stream in a time of austerity, as well as rebuilding the public sphere – councils are perhaps most visible to residents when they close libraries and cut other services.

But there is also a political project afoot as well, as Labour-controlled councils such as Nottingham push an agenda that has since been picked up by Jeremy Corbyn during the last election.

There is also genuine concern over fuel poverty, and a hope that local authorities will be more trusted than the usual energy suppliers, that even Theresa May says have ripped customers off.

“It’s about councils trying to provide a trusted and better service for people to switch. We want a challenger model to the big six,” said Labour MP Caroline Flint, whose Doncaster constituency will see the launch of publicly owned Great Northern Energy on 7 November.

The flurry of such firms showed Labour’s manifesto pledge of a publicly owned energy supplier in each region was happening regardless of the party’s failure to win power in June’s snap general election, Flint said.

Tackling the growing amount of households in fuel poverty, which number 2.5 million in England and Wales, is another big motivation.

Steve Battlemuch, chair of the board of Robin Hood Energy and a Labour councillor, said: “Nottingham has a lot of fuel poverty, lot of people on prepayment meters [which people in energy debt are often moved on to]. That was what drove us: coming into the market and driving down prices for the customer.”

Like other public firms, part of his sales pitch is that there are no corporate masters to pay.

“There’s no shareholder bonuses, because there’s no shareholder apart from Nottingham city council. There’s no director bonuses. I had a cupcake on our first anniversary,” he said.

Peter Haigh, managing director of Bristol Energy, said his organisation was more inclusive than private companies, and its physical presence in the city was a big attraction.

“Customers can and do walk in, sign up and pay a bill. That often attracts customers who have never switched, people who can pop in face to face,” he said.

Part of the reason councils are getting into energy is the barriers to market are not as great as they once were.

Mark Coyle, strategy director of Utiligroup, which has provided services to most of the publicly owned energy companies, said: “We’ve been able to lower the barriers for them, without lowering compliance.”

But while the sector appears to be burgeoning, combined these companies are a minnow compared with the blue whales that are the big six firms, which between them account for 80% share of the market.

Bristol Energy is biggest publicly owned energy supplier, with about 110,000 customers; Robin Hood has just over 100,000. Both have created more than 100 jobs locally, but neither has yet recovered their start-up costs.

Moreover, while such firms appear to be proliferating, most are simply rebranding off Robin Hood rather than setting up as fully licensed suppliers which can buy energy on the wholesale market. The approach has its critics.

“Islington are doing a good thing but it’s a shame that they’ve had to go to Nottingham to buy the energy,” said Caroline Russell, a Green party London assembly member.

Sadiq Khan, London’s mayor, has promised to create an energy company for Londoners, but has been slow to deliver.

Last month he was advised by experts to piggyback off an existing supplier, rather than create his own licensed company. While cheaper and quicker to do, it would also mean he had less power and flexibility to offer something genuinely new and different compared with the 50-plus private firms already in the market.

Nigel Cornwall, founder of energy analysts Cornwall Insight, said that while he was supportive of publicly owned energy companies, it was revealing that many councils were opting to ride on Robin Hood’s coat-tails rather than set up their own licensed firm.

“This is high-risk stuff. The sector is complicated. You [the council] probably don’t have the resources. You’ve probably underestimated the costs. And that’s with costs of entry falling dramatically,” he said.

Cornwall said he was also sceptical as to whether the companies would be sustainable and would become a permanent fixture in the market – but that would not stop them trying.

Battlemuch said: “What we need to do is break through into the mass market. That’s what we’re trying to do.”

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label energy. Show all posts

Showing posts with label energy. Show all posts

Friday, 27 October 2017

Saturday, 23 January 2016

Silence from big six energy firms is deafening

If this were a competitive market, our fuel bills would be £850 a year instead of £1,100

Patrick Collinson in The Guardian

Patrick Collinson in The Guardian

UK consumers are not seeing their tariffs cut despite the fall in wholesale gas and oil prices. Photograph: Alamy

You cannot hope to bribe or twist the British journalist (goes the old quote from Humbert Wolfe) “But, seeing what the man will do unbribed, there’s no occasion to.” Much the same could be said about Britain’s energy companies. You cannot call them a cartel. But seeing what they do without actively colluding, there’s no occasion to.

Almost every day the price of oil and gas falls on global markets. But this has been met with deafening inactivity from the big six energy giants. Their standard tariffs remains stubbornly high, bar tiny cuts by British Gas last year and e.on, this week.

If this were a competitive market, which reflected the 45% fall in wholesale prices seen over the last two years, the average dual-fuel consumer in Britain would be paying £850 or so a year, rather than the £1,100 charged to most customers on standard tariffs.

But it is not a competitive market. The energy giants know that around 70% of customers rarely switch, so they can be very effectively milked through the pricey standard tariff, which is, itself, set at peculiarly similar levels across the big providers. The advent of paperless billing probably helps the companies, too, with busy householders failing to spot that they are paying way over the odds.

The gap between the standard tariffs and the low-cost tariffs is now astounding – £1,100 a year vs £775 a year. Yes, the 30% of households who regularly switch can, and do, benefit. But why must we have a business model where seven out of 10 customers lose out, while three out of 10 gain?

The vast majority would rather have an honest tariff deal where their energy company passes on reductions in wholesale prices without having to go through the rigmarole of switching.

Instead, we have a regulatory set-up which believes that the problem is that not enough of us switch. It thinks that it will be solved by getting that 30% figure up to 50% or more. Unfortunately, too, many regulators have a mindset that is almost ideologically attuned to a belief in the efficacy of markets, and the benefits of competition. If competition is not working, then they think the answer is simply more competition.

What would benefit consumers in these natural monopoly markets would be less competition and more regulation. We now have decades of evidence of how privatised former monopolies behave, and what it tells us is that they are there to benefit shareholders and bonus-seeking management, rather than customers.

In March we will hear from the Competition and Markets Authority about the results of its investigation into the energy market. Maybe it will conclude that privatisation and competition have failed, but my guess is that it won’t. The clue is in the name of the authority.

• A final word about home insurance. Last week I said every insurer is in on the game, happy to rip-off loyal customers, particularly older ones. I received a letter from a 90-year-old householder in Richmond Upon Thames, who, for 20 years has bought home and contents cover from the Ecclesiastical Insurance company.

After seeing my coverage, he nervously checked his premiums, as he had been letting them go through on direct debit for years without scrutiny.

To his delight, he discovered that Ecclesiastical had, unprompted, been cutting his insurance premiums.

One company, at least, doesn’t think it should skin an elderly customer just because it can probably get away with it. We should perhaps praise the lord there is an insurer out there with a conscience.

Is Ecclesiastical the only “ethical” insurer, or are there any others who are not “in on the game”, asks our reader from Richmond. Let me know!

You cannot hope to bribe or twist the British journalist (goes the old quote from Humbert Wolfe) “But, seeing what the man will do unbribed, there’s no occasion to.” Much the same could be said about Britain’s energy companies. You cannot call them a cartel. But seeing what they do without actively colluding, there’s no occasion to.

Almost every day the price of oil and gas falls on global markets. But this has been met with deafening inactivity from the big six energy giants. Their standard tariffs remains stubbornly high, bar tiny cuts by British Gas last year and e.on, this week.

If this were a competitive market, which reflected the 45% fall in wholesale prices seen over the last two years, the average dual-fuel consumer in Britain would be paying £850 or so a year, rather than the £1,100 charged to most customers on standard tariffs.

But it is not a competitive market. The energy giants know that around 70% of customers rarely switch, so they can be very effectively milked through the pricey standard tariff, which is, itself, set at peculiarly similar levels across the big providers. The advent of paperless billing probably helps the companies, too, with busy householders failing to spot that they are paying way over the odds.

The gap between the standard tariffs and the low-cost tariffs is now astounding – £1,100 a year vs £775 a year. Yes, the 30% of households who regularly switch can, and do, benefit. But why must we have a business model where seven out of 10 customers lose out, while three out of 10 gain?

The vast majority would rather have an honest tariff deal where their energy company passes on reductions in wholesale prices without having to go through the rigmarole of switching.

Instead, we have a regulatory set-up which believes that the problem is that not enough of us switch. It thinks that it will be solved by getting that 30% figure up to 50% or more. Unfortunately, too, many regulators have a mindset that is almost ideologically attuned to a belief in the efficacy of markets, and the benefits of competition. If competition is not working, then they think the answer is simply more competition.

What would benefit consumers in these natural monopoly markets would be less competition and more regulation. We now have decades of evidence of how privatised former monopolies behave, and what it tells us is that they are there to benefit shareholders and bonus-seeking management, rather than customers.

In March we will hear from the Competition and Markets Authority about the results of its investigation into the energy market. Maybe it will conclude that privatisation and competition have failed, but my guess is that it won’t. The clue is in the name of the authority.

• A final word about home insurance. Last week I said every insurer is in on the game, happy to rip-off loyal customers, particularly older ones. I received a letter from a 90-year-old householder in Richmond Upon Thames, who, for 20 years has bought home and contents cover from the Ecclesiastical Insurance company.

After seeing my coverage, he nervously checked his premiums, as he had been letting them go through on direct debit for years without scrutiny.

To his delight, he discovered that Ecclesiastical had, unprompted, been cutting his insurance premiums.

One company, at least, doesn’t think it should skin an elderly customer just because it can probably get away with it. We should perhaps praise the lord there is an insurer out there with a conscience.

Is Ecclesiastical the only “ethical” insurer, or are there any others who are not “in on the game”, asks our reader from Richmond. Let me know!

Sunday, 6 December 2015

The India that says no

Tunku Varadarajan in the Indian Express

Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressing during the International Solar Alliance in Paris on Monday. (PTI Photo)

Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressing during the International Solar Alliance in Paris on Monday. (PTI Photo)

As foreign pundits took aim at India, the director of the Indian cricket team was quick to shoot back. “Which rule tells me the ball can’t turn on Day One?” said a mouthy Ravi Shastri. “Where does it tell me in the rulebook it can only swing and seam?” India has to sink or swim when playing abroad, so touring teams should expect no different in India.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressing during the International Solar Alliance in Paris on Monday. (PTI Photo)

Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressing during the International Solar Alliance in Paris on Monday. (PTI Photo)

These last days have seen a fascinating demonstration of righteous assertiveness by Indians. In Paris, Narendra Modi was at the world climate conference defending India’s right to burn coal, it being the cheapest and most profuse of the country’s present sources of energy, entirely mined at home (unlike oil, imported from the world’s volatile hell-holes, and over whose price India has little positive control).

Back in smoggy India, another leader, India’s Test cricket captain Virat Kohli, was defending the country’s repeated resort to slow, turning pitches in the series against South Africa, this type of pitch being the most reliable source of victory at home for the spin-focused Indian cricket team.

In both cases, what we were seeing was a species of indignant, nationalist pushback against standards set by the West, and Western expectations of “fair play” that work to India’s apparent disadvantage.

Modi was blunt and eloquent. Having “powered their way to prosperity on fossil fuel when humanity was unaware of its impact”, he wrote in an op-ed in the Financial Times, it was “morally wrong” of the industrialised West to deny India the right to use the same sources of energy today to pull its people out of poverty. “Justice demands that, with what little carbon we can still safely burn, developing countries are allowed to grow.”

The message embedded here was that the West is guilty of double-standards in seeking to deny India access to the very fuels that had served the occident so well for centuries — and for doing so just as India is primed for a Great Leap Forward. In response to his assertion of India’s transitional developmental rights, Modi earned patronising lectures from the usual suspects, including the tirelessly sanctimonious The New York Times.

Double-standards were also the theme of the Indian cricket complaint. Responding to the barrage of English and Australian criticisms of the Nagpur pitch — where South Africa were spin-dried in just three days — the captain, manager and players of the Indian team took a leaf out of Modi’s book. Why are your standards the norm, they said to Western critics, and our standards — Indian standards — the aberration?

At issue is the belief, rife in English and Australian cricket circles, that green pitches that seam and bounce are fair and manly, the proper surfaces on which to play a game of cricket. These are the pitches one encounters in England and Australia because they are the natural products of local conditions. They also suit the style of play of teams from these countries, while cramping the style of visiting Indian players.

In contrast, Indian pitches are bereft of grass and turn early in a Test match. They are described by foreign cricket writers — often the loudest promoters of the too-much-spin-is-immoral school of thought — as Dust Bowls, conjuring images of famine, and of hardscrabble conditions unsuited to civilised cricket.

As foreign pundits took aim at India, the director of the Indian cricket team was quick to shoot back. “Which rule tells me the ball can’t turn on Day One?” said a mouthy Ravi Shastri. “Where does it tell me in the rulebook it can only swing and seam?” India has to sink or swim when playing abroad, so touring teams should expect no different in India.

As with cricket, so with carbon. “The lifestyles of a few must not crowd out the opportunities for many,” said Modi in Paris. Hands off our coal. And hands off our pitches. This is the India that can say No.

Tuesday, 17 March 2015

She took a year off from her marriage to sleep with strangers. What could go wrong? The Wild Oats Project Review

Carlos Lozada in

The Independent

Get ready for “The

Wild Oats Project”. And not just the book. Get ready for “The Wild Oats

Project” phenomenon — the debates, the think pieces, the imitators and probably

the movie. Get ready for orgasmic meditation and the Three Rules. Get ready for

“My Clitoris Deals Solely in Truth” T-shirts.

Robin Rinaldi, a

magazine journalist living in San Francisco by

way of Scranton , Pa.

“I refuse to go to

my grave with no children and only four lovers,” she declares. “If I can’t have

one, I must have the other.”

If you’re wondering

why that is the relevant trade-off, stop overthinking this. “The Wild Oats

Project” is the year-long tale of how a self-described “good girl” in her early

40s moves out, posts a personal ad “seeking single men age 35-50 to help me

explore my sexuality,” sleeps with roughly a dozen friends and strangers, and

joins a sex commune, all from Monday to Friday, only to rejoin Scott on

weekends so they can, you know, work on their marriage.

The arrangement is

unorthodox enough to succeed as a story, and in Rinaldi’s telling it unfolds as

a sexual-awakening romp wrapped in a female-empowerment narrative, a sort of

Fifty Shades of Eat, Pray, Love. “I wanted to tell him to f— me hard but I

couldn’t get the words out of my mouth” is a typical Rinaldi dilemma. At the

same time, she constantly searches for “feminine energy” or her “feminine core”

or for a “spiritual practice guided by the feminine.

But more than

empowering or arousing, this story is depressing. Rinaldi just seems lost.

Still sorting through the psychological debris of an abusive childhood, she

latches on to whatever guru or beliefs she encounters, and imagines fulfillment

with each new guy. She still rushes to Scott whenever things gets scary (a car

accident, an angry text message), yet deliberately strains their union beyond

recovery. “At any cost” are the operative words of the subtitle.

Robin and Scott

agree to three rules — “no serious involvements, no unsafe sex, no sleeping

with mutual friends” — that both go on to break. He finds a steady girlfriend,

while Robin violates two rules right away. “In truth, I was sick of protecting

things,” she writes about going condom-free with a colleague at a conference.

“I wanted the joy of being overcome.”

The men and women

she hooks up with — some whose names Rinaldi has changed, others too fleeting

to merit aliases — all blur into a new-age, Bay Area cliche. Everyone is a

healer, or a mystic, or a doctoral student in feminist or Eastern spirituality.

They’re all verging on enlightenment, sensing mutual energy, getting copious

action to the sounds of tribal drums. The project peaks when she moves into

OneTaste, an urban commune where “expert researchers” methodically stroke rows

of bare women for 15 minutes at a time in orgasmic meditation sessions (“OM ” to those in the know). “Everyone here was

passionate,” Rinaldi writes. “Everyone had abandoned convention.”

Rinaldi holds

little back, detailing her body’s reactions along the way. At first she is

upset that she can’t feel pleasure as quickly as other women, but she finally

decides she’s glad that her “surrender didn’t happen easily, that it lay buried

and tethered to the realities of each relationship.” Her clitoris, although

“moody,” was also “an astute barometer. . . . It dealt solely in truth.”

And truth often

comes in tacky dialogue. “Your breasts are amazing,” one of her younger

partners tells her. “You should have seen them in my twenties,” Rinaldi boasts.

His comeback: “You’re cocky. I dig that.” (Fade to dirty talk.) When they do it

again months later, he thanks her in the morning. “Something happens when I’m

with you,” he says. “I feel healed.” I’m sure that’s exactly what he feels.

Rinaldi can’t seem

to decide why she’s doing all this. The project is her “rebellion.” Or “a

search for fresh, viable sperm.” Or a “bargaining chip.” Or “an elaborate

attempt to dismantle the chains of love.” Or just a “quasi-adolescent quest for

god knows what.”

If exasperation

could give you orgasms, this book would leave me a deeply satisfied reader.

One of her oldest

friends calls her out. “How is sleeping with a lot of guys going to make you

feel better about not having kids?” she asks. Rinaldi’s answer: “Sleeping with

a lot of guys is going to make me feel better on my deathbed. I’m going to feel

like I lived, like I didn’t spend my life in a box. If I had kids and grandkids

around my deathbed, I wouldn’t need that. Kids are proof that you’ve lived.”

It’s a bleak and disheartening rationale, as though women’s lives can achieve

meaning only through motherhood or sex.

For all her preoccupation

with feminine energy, Rinaldi seems conflicted over feminism. “I would die a

feminist,” she writes of her collegiate activism, “but I was long overdue for

some fun.” Later, she pictures women’s studies scholars judging her submission

fantasies, and frets over “those Afghan women hidden under their burqas” who

could be “beaten or even killed right now for doing what I was so casually

doing.” But when she finds a sexual connection with a woman who backs away

because of “emotional issues,” Rinaldi channels her inner alpha male: “I was

drawn to her body but shrunk back when she expressed unfettered feeling. . . .

It only took sleeping with one woman to help me understand the behavior of

nearly every man I’d ever known.”

When the year runs

out, Rinaldi returns to Scott, even though she soon starts an affair with a

project flame. She’s no longer so upset about the vasectomy, regarding it as a

sign that Scott can stand up for himself (though it may also mean she now cares

less about him, period). No shock that post-project, their chemistry is off,

and when Rinaldi makes a casual reference to their time apart, Scott finally

explodes. “Do you know how many nights I cried myself to sleep when you moved

out!?” he asks. “Do you care about anyone’s feelings but your own!?” She was

“too stunned to reply.” But the fate of this marriage, revealed in the final

pages, is anything but stunning.

“These are the sins

against my husband,” Rinaldi recounts. “Abdicating responsibility, failing to

empathize with him, cheating and lying.” After blaming him for so long, “in the

end, I was the one who needed to ask forgiveness.”

In a rare moment of

heartbreaking subtlety, the book’s dedication page simply says “For Ruby,” the

name Rinaldi had imagined for a baby girl. Except, “there is no baby,” she

writes at the end. “Instead there is the book you hold in your hands.”

And that is a

frustrating book, with awkward prose, a perplexing protagonist and too many

eye-rolling moments. Yet it is also a book I see launching book-club conversations

and plenty of pillow talk — not just about sex and marriage, but about the

price and possibility of self-reinvention. You don’t have to write a great work

to cause a great stir.

Does Rinaldi

reinvent herself? She survives the aftershocks and even seems to discover some

happiness, however fragile she knows it to be. So maybe she needed this after

all. Or maybe sometimes “empowerment” is just another word for self-absorption.

Tuesday, 24 February 2015

Are low oil prices here to stay?

By Richard Anderson

Business reporter, BBC News

Predicting the oil price is a bit of a mug's game.

There are simply too many variables involved to make any kind of meaningful, definitive forecast.

What we do know is that, despite a recent upturn, the price of oil has slumped almost 50% since last summer following the longest-running decline for 20 years.

And we know why - US shale oil, and to a lesser extent Libyan oil returning to the market, has pushed up supply while a slowdown in the Chinese and EU economies has reduced demand.

Add to the mix a strong US dollar making oil more expensive in real terms, pushing demand even lower, and you have a recipe for a plummeting oil price.

What happens next is a little harder to see.

With the booming US shale industry showing little signs of slowing, and growing concerns about the strength of the global economy, there are good reasons to suspect that the current slump in the oil price will continue for some time.

This is precisely when Opec, the cartel of major global oil producers, would normally step in to stabilise prices by cutting production. It has done so many times in the past, so often in fact that the market expects Opec to intervene.

This time it hasn't. In a historic move at the end of last year, Opec said not only that it would not cut production from its 30 million barrels a day (mb/d) quota, but had no intention of doing so even if oil fell to $20 a barrel.

And this was no empty threat. Despite furious opposition from Venezuela, Iran and Algeria, Opec kingpin Saudi Arabia simply refused to bail out its more vulnerable cohorts - many Opec members need an oil price of $100 or more to balance their budgets, but with an estimated $900bn in reserves, Saudi can afford to play the waiting game.

Opec now supplies a little over 30% of the world's oil, down from almost 50% in the 1970s, partly due to US shale producers flooding the market with almost 4 mb/d from a standing start 10 years ago.

"Given this scenario, who should be expected to cut production to put a floor under prices?" Opec argued last month.

Equally, Saudi is not prepared to sacrifice more market share while its competitors, not least US shale oil producers, prosper. Safe in the knowledge that it can withstand very low oil prices for the best part of a decade, it would rather stand back and, as Philip Whittaker at Boston Consulting Group says, "let economics do the work".

The implications of Opec's decision, therefore, go way beyond sending the oil price crashing even further.

"We have entered a new chapter in the history of the oil market, which is now starting to operate like any non-cartel commodity market," says Stuart Elliott at energy specialist Platts.

The fallout has been immediate in many parts of the industry, and promises to wreak further havoc in the coming months and, quite possibly, years.

'Serious risks'

Without Opec artificially supporting the oil price, and with potentially weaker demand due to sluggish global economic growth, the oil price is likely to remain below $100 for years to come.

The futures market suggests the price will recover slowly to hit about $70 by 2019, while most experts forecast a range of $40-$80 for the next few years. Anything more precise is futile.

At these kinds of prices, a great many oil wells become uneconomic. First at risk are those developing hard to access reserves, such as deepwater wells. Arctic oil, for example, does not work at less than $100 a barrel, says Brendan Cronin at Poyry Managing Consultants, so any plans for polar drilling are likely to be shelved for the foreseeable future.

World's top oil producers, 2014 (million barrels a day)- US: 11.75

- Russia: 10.93

- Saudi Arabia: 9.53

- China: 4.20

- Canada: 4.16

- Iraq: 3.33

- Iran: 2.81

- Mexico: 2.78

- UAE: 2.75

- Kuwait: 2.61

Source: IEA

North Sea oil production is also at serious risk, certainly in terms of new wells that need an oil price of about $70-$80 to justify drilling. Indeed in a recent interview with Platts, the head of Oil & Gas UK said at $50, North Sea oil production could fall by 20%, dealing a hammer blow not just to the companies involved but to the Scottish economy as a whole.

Exploration into unproven reserves in regions such as Southern and West Africa will also grind to a halt.

Questions are also being asked about fracking. Costs vary a great deal, but research by Scotiabank suggests the average breakeven price for US shale producers is about $60. At the same price, energy research group Wood Mackenzie estimates that investment in new wells would halve, wiping out production growth.

"The vast majority [of US shale wells] just don't work at $40-$50," says Mr Cronin.

Oil majors are already suffering, having announced tens of billions of dollars of cuts in exploration spending. But while the share prices of BP, Total and Chevron are all down about 15% since last summer, the majors have the resources to see out a sustained period of low oil prices.

There are hundreds of other much smaller oil groups across the world with a far more uncertain future, not least in the US. Shale companies there have borrowed $160bn in the past five years, all predicated on selling oil at a higher price than we have today. Banks' patience can only be tested so far.

Oilfield services companies are also "feeling severe pain", according to Mr Whittaker, with share prices in the sector down an average 30%-50%. Last month, US giant Schlumberger announced 9,000 job cuts, some 8% of its entire workforce.

But it's not just oil companies that are being hit by lower oil prices - the renewables sector is suffering as well.

In the Middle East and parts of Central and South America, oil is in direct competition with renewables to generate electricity, so solar power in particular will suffer at the hands of cheap oil.

Fuel price calculator

Elsewhere, falling oil prices are helping drive down the price of gas, the direct rival of renewables. Subsidies, therefore, may have to rise to compensate.

Indeed lower oil and gas prices undermine a fundamental economic argument propounded by many governments to support renewables - that fossil fuels will continue to rise in price.

The impact is already being felt - shares in Vestas, the world's largest wind turbine manufacturer, are down 15% since the summer, while those in Chinese solar panel giant JA Solar have slumped 20%.

Lower oil prices are also a grave concern for electric carmakers, with sales of hybrids in the US falling while those of gas-guzzling SUVs surge.

'Profound impact'

The knock-on effects within the energy industry of a sustained period of lower oil prices are, then, both widespread and profound.

But while Saudi Arabia's decision to call time on supporting the oil price marks an important milestone in the industry, oil's self-stabilising price mechanism remains very much intact - prices fall, production drops, supply falls, prices rise.

As a direct result of lower prices, exploration and production will be curtailed, and while it may take a number of years to filter through, supply will fall and prices will rise. After all, while there may be hundreds of new small suppliers entering the fray, there are still too few big players controlling oil supply for a truly free market to develop.

But real change is on the way. There is a growing realisation that fossil fuels need to be left in the ground if the world is to meet climate change targets and avoid dangerous levels of global warming.

Against this backdrop, it is only a matter of time before a meaningful carbon price - hitting polluters for emitting CO2 - is introduced, a price that will have a profound impact on the global oil market.

Equally, for the first time oil is facing a genuine competitor in the transport sector, which currently accounts for more than half of all oil consumption. Electric vehicles may be a niche market now, but as battery technology in particular advances, they will move inexorably into the mainstream, significantly reducing demand for oil.

The oil market is undergoing significant transformation, but more fundamental change is on the horizon.

Sunday, 2 March 2014

Free Lunches - Modi's Crony Capitalism

Lola Nayyar in Outlook India

During the Vibrant Gujarat summit in 2011, Gujarat chief minister Narendra Modi was seen being venerated by the bigwigs of Indian industry, from Ratan Tata to Mukesh Ambani, for his grand vision of development. It figures. The development model has increasingly come to be skewed in favour of capital-intensive mega industries.

This is evident not just in project allocation but also in terms of resources, be it finances, subsidies, land or natural wealth. If Adani tops the list of Modi’s favourites in popular perception, the Ambanis, Tatas, Essar, Torrent Power follow closely. Many like Welspun, Zydus Cadila, Nirma, Lalbhais etc are giving way to others as front-runners for subsidies that are huge by any standard, whether capital subsidy, interest subsidy, infrastructure subsidy, sales tax and now VAT subsidy. The capital is being provided at just 0.1 per cent interest with an average of a 20-year moratorium on repayment, stretched in some cases to over 40 years. Besides land, water and other natural resources come at throwaway prices.

A rough calculation of the subsidy the Tatas effectively got to set up their Nano manufacturing plant in Gujarat pegs it at around Rs 33,000 crore, say local politicians. “Historically, the Gujarat model was to promote smes in backward areas, but over the years premier, prestigious and now mega industries are being promoted in the state. Starting from the Tatas’ Nano project, the share of subsidy and incentives has become tilted in favour of mega projects—the greater the investment, the greater is the rate of subsidy,” says Prof Indira Hirway of the Centre for Development Alternatives, Ahmedabad.

Because competitive forces do not dictate the allocation of resources, favours determine the slice of the cake. This has resulted in the suboptimal allocation of resources. As capital has become cheaper, it has become more profitable for corporates to go in for capital-intensive industries with little employment generation. The huge outgo in corporate and infrastructure subsidies has also meant few resources are left for social development, whether health or education.

“Modi seems to practise a lot of crony capitalism, but knows very little about capitalism, which involves liberalism and spiritualism—none of which applies to him,” says Rajiv Desai, CEO of Comma Consulting.

Industrial growth in Gujarat, going by the last two audit reports of state psus by the Comptroller and Auditor General, is coming at a high cost to the exchequer. In 2012, the CAG took a critical view of the Modi government’s mismanagement resulting in losses of over Rs 16,000 crore.

In the case of the state-owned Gujarat State Petroleum Corporation (GSPC), the audit report is critical of “undue benefits” extended to favoured corporates like Adani Energy and Essar Steel. The report points out that GSPC purchased natural gas from the spot market at the prevailing prices and sold it to Adani Energy at a fixed price much lower than the market price, benefiting the latter to the tune of over Rs 70 crore. To Essar Steel, the corporation extended undue benefits of over Rs 12.02 crore by way of a waiver of capacity charges, contrary to the provisions of the gas transmission agreement.

Again in 2013, the CAG took a critical view of state public sector undertakings extending undue favours to Reliance Industries and Adani Power Ltd (APL). It highlighted a loss of Rs 52.27 crore due to a retweaking of the gas transportation agreement (GTA) with RIL for transportation of D6 gas from Bhadbhut in Bharuch district to RIL’s Jamnagar refinery.

In the case of Gujarat Urja Vikas Nigam Limited (GUVNL), over Rs 160 crore was lost by not levying a penalty on APL for violation of the power purchase agreement.

Experts point out how major projects in the state are increasingly being captured by a few favourite industrial groups, which have been witnessing faster than their average growth just a decade back. Paying the price is the aam aadmi. Take the sale of CNG in Ahmedabad. It’s more expensive than in Delhi despite the fact that most of the gas is transported via pipeline to the capital from Gujarat. A reason assigned by the locals is that the cng vending stations are largely operated by the Adanis.

During the Vibrant Gujarat summit in 2011, Gujarat chief minister Narendra Modi was seen being venerated by the bigwigs of Indian industry, from Ratan Tata to Mukesh Ambani, for his grand vision of development. It figures. The development model has increasingly come to be skewed in favour of capital-intensive mega industries.

This is evident not just in project allocation but also in terms of resources, be it finances, subsidies, land or natural wealth. If Adani tops the list of Modi’s favourites in popular perception, the Ambanis, Tatas, Essar, Torrent Power follow closely. Many like Welspun, Zydus Cadila, Nirma, Lalbhais etc are giving way to others as front-runners for subsidies that are huge by any standard, whether capital subsidy, interest subsidy, infrastructure subsidy, sales tax and now VAT subsidy. The capital is being provided at just 0.1 per cent interest with an average of a 20-year moratorium on repayment, stretched in some cases to over 40 years. Besides land, water and other natural resources come at throwaway prices.

A rough calculation of the subsidy the Tatas effectively got to set up their Nano manufacturing plant in Gujarat pegs it at around Rs 33,000 crore, say local politicians. “Historically, the Gujarat model was to promote smes in backward areas, but over the years premier, prestigious and now mega industries are being promoted in the state. Starting from the Tatas’ Nano project, the share of subsidy and incentives has become tilted in favour of mega projects—the greater the investment, the greater is the rate of subsidy,” says Prof Indira Hirway of the Centre for Development Alternatives, Ahmedabad.

Because competitive forces do not dictate the allocation of resources, favours determine the slice of the cake. This has resulted in the suboptimal allocation of resources. As capital has become cheaper, it has become more profitable for corporates to go in for capital-intensive industries with little employment generation. The huge outgo in corporate and infrastructure subsidies has also meant few resources are left for social development, whether health or education.

“Modi seems to practise a lot of crony capitalism, but knows very little about capitalism, which involves liberalism and spiritualism—none of which applies to him,” says Rajiv Desai, CEO of Comma Consulting.

Industrial growth in Gujarat, going by the last two audit reports of state psus by the Comptroller and Auditor General, is coming at a high cost to the exchequer. In 2012, the CAG took a critical view of the Modi government’s mismanagement resulting in losses of over Rs 16,000 crore.

In the case of the state-owned Gujarat State Petroleum Corporation (GSPC), the audit report is critical of “undue benefits” extended to favoured corporates like Adani Energy and Essar Steel. The report points out that GSPC purchased natural gas from the spot market at the prevailing prices and sold it to Adani Energy at a fixed price much lower than the market price, benefiting the latter to the tune of over Rs 70 crore. To Essar Steel, the corporation extended undue benefits of over Rs 12.02 crore by way of a waiver of capacity charges, contrary to the provisions of the gas transmission agreement.

Again in 2013, the CAG took a critical view of state public sector undertakings extending undue favours to Reliance Industries and Adani Power Ltd (APL). It highlighted a loss of Rs 52.27 crore due to a retweaking of the gas transportation agreement (GTA) with RIL for transportation of D6 gas from Bhadbhut in Bharuch district to RIL’s Jamnagar refinery.

In the case of Gujarat Urja Vikas Nigam Limited (GUVNL), over Rs 160 crore was lost by not levying a penalty on APL for violation of the power purchase agreement.

Experts point out how major projects in the state are increasingly being captured by a few favourite industrial groups, which have been witnessing faster than their average growth just a decade back. Paying the price is the aam aadmi. Take the sale of CNG in Ahmedabad. It’s more expensive than in Delhi despite the fact that most of the gas is transported via pipeline to the capital from Gujarat. A reason assigned by the locals is that the cng vending stations are largely operated by the Adanis.

Sunday, 29 December 2013

Food banks in the UK: cowardly coalition can't face the truth about them

Conservatives cannot admit a real fear of hunger afflicts thousands

Donated food at a a food bank. Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian

I went to the Trussell Trust food bank round the corner from the Observer's offices just before Christmas. If I hadn't been reading the papers, I would have assumed it represented everything Conservatives admire. As at every other food bank, volunteers who are overwhelmingly churchgoers ran it and organised charitable donations from the public.

What could be closer to Edmund Burke's vision of the best of England that David Cameron says inspired his "big society"? You will remember that in his philippic against the French revolution, Burke said his contemporaries should reject its dangerously grandiose ambitions , and learn that "to love the little platoons we belong to in society, is the first principle (the germ, as it were) of public affections". Yet when confronted with displays of public affection – not in 1790 but in 2013 – the coalition turns its big guns on the little platoons.

It would have been easy for the government to say that it was concerned that so many had become so desperate. This was Britain, minsters might have argued, not some sun-beaten African kleptocracy. Regardless of politics, it was a matter of common decency and national pride that Britain should not be a land where hundreds of thousands cannot afford to eat. The coalition might not have meant every word or indeed any word. But it would have been in its self-interest to emit a few soothing expressions of concern, and offer a few tweaks to an inhumanely inefficient benefits system, if only to allay public concern about the rotten state of the nation.

But the coalition is not even prepared to play the hypocrite. Iain Duncan Smith showed why he never won the VC when he was in the Scots Guards when he refused to face the Labour benches as the Commons debated food banks on 18 December. He pushed forward his deputy, one Esther McVey, a former "TV personality". All she could say was that hunger was Labour's fault for wrecking the economy. She gave no hint that her government had been in power for three years during which the number attending food banks had risen from 41,000 in 2010 to more than 500,000. Her remedy was for the coalition to help more people into work.

If she had bothered talking to the Trussell Trust, it would have told her that low-paid work is no answer. Its 1,000 or so distribution points serve working families, who have no money left for food once they have paid exorbitant rent and fuel bills.

But then no one in power wants to talk to the trust. As the Observer revealed, Chris Mould, its director, wrote to Duncan Smith asking if they could discuss cheap ways of reducing hunger: speeding up appeals against benefit cuts; or stopping the endemic little Hitlerism in job centres, which results in unjust punishments for trivial transgressions. In other words, a Christian charity, which was turning the "big society" from waffle into a practical reality, was making a civil request. Duncan Smith responded with abuse. The charity's claims to be "non-partisan" were a sham, he said. The Trussell Trust was filled with "scaremongering" media whores, desperate to keep their names in the papers. But he had their measure.

Oh, yes. "I understand that a feature of your business model must require you to continuously achieve publicity, but I'm concerned that you are now seeking to do this by making your political opposition to welfare reform overtly clear."

Ministers will not confess to making a mistake for fear of damaging their careers. But it is not only their reputations but an entire world view that is at stake. Put bluntly, the Conservatives hope to scrape the 2015 election by convincing a large enough minority that welfare scroungers are stealing their money. They cannot admit that a real fear of hunger afflicts hundreds of thousands. Hence, Lord Freud, the government's adviser on welfare reform, had to explain away food banks by saying: "There is an almost infinite demand for a free good."

My visit to the food bank showed that our leaders' ignorance has become a deliberate refusal to face a social crisis. Of course, the volunteers help working families and students as well as the unemployed and pensioners. Everyone apart from ministers knows about in-work poverty. As preposterous is the Tory notion that the banks are filled with freeloaders.

You cannot just swan in. You get nothing unless a charity or public agency has assessed your need and given you a voucher. The trust is at pains to make sure that the beggars – for hundreds of thousands of beggars is what Britain now has – receive a balanced diet. To feed a couple for five days, it gives: one medium pack of cereal, 80 teabags, a carton of milk, two cans apiece of soup, beans, tomatoes and vegetables, two portions of meat and fish, fruit, rice pudding, sugar, pasta and juice. That this is hardly a feast is confirmed by the short list of "treats", which, "when available", consist of "one bar of chocolate and one jar of jam".

Sharon Cumberbatch, who runs the centre, tells me that she is so worried that shame will deter her potential clients that she packages food in supermarket bags so no one need know its source. The clients, when I met them, reinforced her point that they were not the brazen freeloaders of Tory nightmare. They trembled when they told me how they did not know how they would make it into the new year.

Most of all, it was the volunteers who were a living reproof to a coalition that can cannot correct its errors. They not only distribute food but collect it. They stand outside supermarkets all day asking strangers to buy the tinned food they need or hand out leaflets in the streets or plead with businesses to help. Sharon Cumberbatch is unemployed but she works to help others for nothing. Her colleagues said they manned the bank because hunger in modern Britain was a sign of a country that was falling apart. Or as one volunteer, Richard Moorhead, put it to me: "I am gobsmacked that people are going hungry. I'm ashamed."

The coalition can call such attitudes political if it wants – in the broadest sense they are. But they are also patriotic, neighbourly, charitable and kind. They come from people who represent a Britain the Conservative party once claimed a kinship with, and now cannot bring itself to talk to.

Tuesday, 12 November 2013

It's business that really rules us now

Lobbying is the least of it: corporate interests have captured the entire democratic process. No wonder so many have given up on politics

‘Tony Blair and Gordon Brown purged the party of any residue of opposition to corporations and the people who run them. That's what New Labour was all about.' Photograph: Sean Dempsey/PA

It's the reason for the collapse of democratic choice. It's the source of our growing disillusionment with politics. It's the great unmentionable. Corporate power. The media will scarcely whisper its name. It is howlingly absent from parliamentary debates. Until we name it and confront it, politics is a waste of time.

The political role of business corporations is generally interpreted as that of lobbyists, seeking to influence government policy. In reality they belong on the inside. They are part of the nexus of power that creates policy. They face no significant resistance, from either government or opposition, as their interests have now been woven into the fabric of all three main political parties in Britain.

Most of the scandals that leave people in despair about politics arise from this source. On Monday, for instance, the Guardian revealed that the government's subsidy system for gas-burning power stations is being designed by an executive from the Dublin-based company ESB International, who has been seconded into the Department of Energy. What does ESB do? Oh, it builds gas-burning power stations.

On the same day we learned that a government minister, Nick Boles, has privately assured the gambling company Ladbrokes that it needn't worry about attempts by local authorities to stop the spread of betting shops. His new law will prevent councils from taking action.

Last week we discovered that G4S's contract to run immigration removal centres will be expanded, even though all further business with the state was supposed to be frozen while allegations of fraud were investigated.

Every week we learn that systemic failures on the part of government contractors are no barrier to obtaining further work, that the promise of efficiency, improvements and value for money delivered by outsourcing and privatisation have failed to materialise.

The monitoring which was meant to keep these companies honest is haphazard, the penalties almost nonexistent, the rewards can be stupendous, dizzying, corrupting. Yet none of this deters the government. Since 2008, the outsourcing of public services has doubled, to £20bn. It is due to rise to £100bn by 2015.

This policy becomes explicable only when you recognise where power really lies. The role of the self-hating state is to deliver itself to big business. In doing so it creates a tollbooth economy: a system of corporate turnpikes, operated by companies with effective monopolies.

It's hardly surprising that the lobbying bill – now stalled by the House of Lords – offered almost no checks on the power of corporate lobbyists, while hog-tying the charities who criticise them. But it's not just that ministers are not discouraged from hobnobbing with corporate executives: they are now obliged to do so.

Thanks to an initiative by Lord Green, large companies have ministerial "buddies", who have to meet them when the companies request it. There were 698 of these meetings during the first 18 months of the scheme, called by corporations these ministers are supposed be regulating. Lord Green, by the way, is currently a government trade minister. Before that he was chairman of HSBC, presiding over the bank while it laundered vast amounts of money stashed by Mexican drugs barons. Ministers, lobbyists – can you tell them apart?

That the words corporate power seldom feature in the corporate press is not altogether surprising. It's more disturbing to see those parts of the media that are not owned by Rupert Murdoch or Lord Rothermere acting as if they are.

For example, for five days every week the BBC's Today programme starts with a business report in which only insiders are interviewed. They are treated with a deference otherwise reserved for God on Thought for the Day. There's even a slot called Friday Boss, in which the programme's usual rules of engagement are set aside and its reporters grovel before the corporate idol. Imagine the outcry if Today had a segment called Friday Trade Unionist or Friday Corporate Critic.

This, in my view, is a much graver breach of BBC guidelines than giving unchallenged airtime to one political party but not others, as the bosses are the people who possess real power – those, in other words, whom the BBC has the greatest duty to accost. Research conducted by the Cardiff school of journalism shows business representatives now receive 11% of airtime on the BBC's 6 o'clock news (this has risen from 7% in 2007), while trade unionists receive 0.6% (which has fallen from 1.4%). Balance? Impartiality? The BBC puts a match to its principles every day.

And where, beyond the Green party, Plaid Cymru, a few ageing Labour backbenchers, is the political resistance? After the article I wrote last week, about the grave threat the transatlantic trade and investment partnership presents to parliamentary sovereignty and democratic choice, several correspondents asked me what response there has been from the Labour party. It's easy to answer: nothing.

Tony Blair and Gordon Brown purged the party of any residue of opposition to corporations and the people who run them. That's what New Labour was all about. Now opposition MPs stare mutely as their powers are given away to a system of offshore arbitration panels run by corporate lawyers.

Since Blair, parliament operates much as Congress in the United States does: the lefthand glove puppet argues with the right hand glove puppet, but neither side will turn around to face the corporate capital that controls almost all our politics. This is why the assertion that parliamentary democracy has been reduced to a self-important farce has resonated so widely over the past fortnight.

So I don't blame people for giving up on politics. I haven't given up yet, but I find it ever harder to explain why. When a state-corporate nexus of power has bypassed democracy and made a mockery of the voting process, when an unreformed political funding system ensures that parties can be bought and sold, when politicians of the three main parties stand and watch as public services are divvied up by a grubby cabal of privateers, what is left of this system that inspires us to participate?

Wednesday, 23 October 2013

Sir John Major gets his carefully-crafted revenge on the bastards

Tory former prime minister's speech was a nostalgic trip down memory lane, where he mugged the Eurosceptics

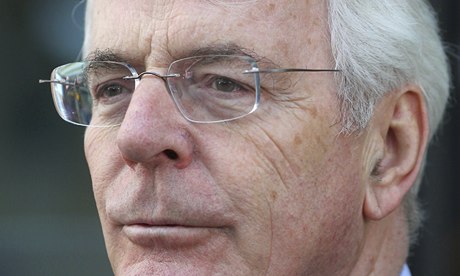

Sir John Major made a lunchtime speech in parliament in which he got his revenge on the Eurosceptics and other enemies Photograph: Gareth Fuller/PA

John Major, our former prime minister, was in reflective mood at a lunch in parliament. Asked about his famous description of Eurosceptics as "bastards", he remarked ruefully: "What I said was unforgivable." Pause for contrition. "My only excuse – is that it was true." Pause for loud laughter. Behind that mild demeanour, he is a good hater.

The event was steeped in nostalgia. Sir John may have hair that is more silvery than ever, and his sky-blue tie shines like the sun on a tropical sea at daybreak, but he still brings a powerful whiff of the past. Many of us can recall those days of the early 1990s. Right Said Fred topped the charts with Deeply Dippy, still on all our lips. The top TV star was Mr Blobby. The Ford Mondeo hit the showrooms, bringing gladness and stereo tape decks to travelling salesmen. Unemployment nudged 3 million.

Sir John dropped poison pellets into everyone's wine glass. But for a while he spoke only in lapidary epigrams. "The music hall star Dan Leno said 'I earn so much more than the prime minister; on the other hand I do so much less harm'."

"Tories only ever plot against themselves. Labour are much more egalitarian – they plot against everyone."

"The threat of a federal Europe is now deader than Jacob Marley."

"David Cameron's government is not Conservative enough. Of course it isn't; it's a coalition, stupid!"

Sometimes the saws and proverbs crashed into each other: "If we Tories navel-gaze and only pander to our comfort zone, we will never get elected."

And in a riposte to the Tebbit wing of the Tory party (now only represented by another old enemy, Norman Tebbit): "There is no point in telling people to get on their bikes if there is nowhere to live when they get there."

He was worried about the "dignified poor and the semi-poor", who, he implied, were ignored by the government. Iain Duncan Smith, leader of the bastards outside the cabinet during the Major government, was dispatched. "IDS is trying to reform benefits. But unless he is lucky or a genius, which last time I looked was not true, he may get things wrong." Oof.

"If he listens only to bean-counters and cheerleaders only concerned with abuse of the system, he will fail." Ouch!

"Governments should exist to help people, not institutions."

But he had kind words for David or Ed, "or whichever Miliband it is". Ed's proposal for an energy price freeze showed his heart was in the right place, even if "his head has gone walkabout".

He predicted a cold, cold winter. "It is not acceptable for people to have to make a choice between eating and heating." His proposal, a windfall tax, was rejected by No 10 within half an hour of Sir John sitting down.

Such is 24-hour news. Or as he put it: "I was never very good at soundbites – if I had been, I might have felt the hand of history on my shoulder." And having laid waste to all about him, he left with a light smile playing about his glistening tie.

-------

Steve Richards in The Independent

Former Prime Ministers tend to have very little impact on the eras that follow them. John Major is a dramatic exception. When Major spoke in Westminster earlier this week he offered the vividly accessible insights of a genuine Conservative moderniser. In doing so he exposed the narrow limits of the self-proclaimed modernising project instigated by David Cameron and George Osborne. Major’s speech was an event of considerable significance, presenting a subtle and formidable challenge to the current leadership. Margaret Thatcher never achieved such a feat when she sought – far more actively – to undermine Major after she had suddenly become a former Prime Minister.

The former Prime Minister’s call for a one-off tax on the energy companies was eye-catching, but his broader argument was far more powerful. Without qualification, Major insisted that governments had a duty to intervene in failing markets. He made this statement as explicitly as Ed Miliband has done since the latter became Labour’s leader. The former Prime Minister disagrees with Miliband’s solution – a temporary price freeze – but he is fully behind the proposition that a government has a duty to act. He stressed that he was making the case as a committed Conservative.

Yet the proposition offends the ideological souls of those who currently lead the Conservative party. Today’s Tory leadership, the political children of Margaret Thatcher, is purer than the Lady herself in its disdain for state intervention. In developing his case, Major pointed the way towards a modern Tory party rather than one that looks to the 1980s for guidance. Yes, Tories should intervene in failing markets, but not in the way Labour suggests. He proposes a one-off tax on energy companies. At least he has a policy. In contrast, the generation of self-proclaimed Tory modernisers is paralysed, caught between its attachment to unfettered free markets and the practical reality that powerless consumers are being taken for a ride by a market that does not work.

Major went much further, outlining other areas in which the Conservatives could widen their appeal. They included the case for a subtler approach to welfare reform. He went as far as to suggest that some of those protesting at the injustice of current measures might have a point. He was powerful too on the impoverished squalor of some people’s lives, and on their sense of helplessness – suggesting that housing should be a central concern for a genuinely compassionate Conservative party. The language was vivid, most potently when Major outlined the choice faced by some in deciding whether to eat or turn the heating on. Every word was placed in the wider context of the need for the Conservatives to win back support in the north of England and Scotland.

Of course Major had an agenda beyond immediate politics. Former prime ministers are doomed to defend their record and snipe at those who made their lives hellish when they were in power. Parts of his speech inserted blades into old enemies. His record was not as good as he suggested, not least in relation to the abysmal state of public services by the time he left in 1997. But the period between 1990, when Major first became Prime Minister, and the election in 1992 is one that Tories should re-visit and learn from. Instead it has been virtually airbrushed out of their history.

In a very brief period of time Major and his party chairman Chris Patten speedily changed perceptions of their party after the fall of Margaret Thatcher. Major praised the BBC, spoke of the need to be at the heart of Europe while opting out of the single currency, scrapped the Poll Tax, placed a fresh focus on the quality of public services through the too easily derided Citizens’ Charter, and sought to help those on benefits or low incomes. As Neil Kinnock reflected later, voters thought there had been a change of government when Major replaced Thatcher, making it more difficult for Labour to claim that it was time for a new direction.

The key figures in the Conservative party were Major, Patten, Michael Heseltine, Ken Clarke and Douglas Hurd. Now it is Cameron, George Osborne, Michael Gove, William Hague, Iain Duncan Smith, Oliver Letwin and several others with similar views. They include Eurosceptics, plus those committed to a radical shrinking of the state and to transforming established institutions. All share a passion for the purity of markets in the public and private sectors. Yet in the Alice in Wonderland way in which politics is reported, the current leadership is portrayed as “modernisers” facing down “the Tory right”.

The degree to which the debate has moved rightwards at the top of the Conservative party and in the media can be seen from the bewildered, shocked reaction to Nick Clegg’s modest suggestion that teachers in free schools should be qualified to teach. The ideologues are so unused to being challenged they could not believe such comments were being made. Instead of addressing Clegg’s argument, they sought other reasons for such outrageous suggestions. Clegg was wooing Labour. Clegg was scared that his party would move against him. Clegg was seeking to woo disaffected voters. The actual proposition strayed well beyond their ideological boundaries.

This is why Major’s intervention has such an impact. He exposed the distorting way in which politics is currently reported. It is perfectly legitimate for the current Conservative leadership to seek to re-heat Thatcherism if it wishes to do so, but it cannot claim to be making a significant leap from the party’s recent past.

Nonetheless Cameron’s early attempts to embark on a genuinely modernising project are another reason why he and senior ministers should take note of what Major says. For leaders to retain authority and authenticity there has to be a degree of coherence and consistency of message. In his early years as leader, Cameron transmitted messages which had some similarities with Major’s speech, at least in terms of symbolism and tone. Cameron visited council estates, urged people to vote blue and to go green, spoke at trade union conferences rather than to the CBI, played down the significance of Europe as an issue, and was careful about how he framed his comments on immigration. If he enters the next election “banging on” about Europe, armed with populist policies on immigration while bashing “scroungers” on council estates and moaning about green levies, there will be such a disconnect with his earlier public self that voters will wonder about how substantial and credible he is.

Cameron faces a very tough situation, with Ukip breathing down his neck and a media urging him rightwards. But the evidence is overwhelming. The one-nation Major was the last Tory leader to win an overall majority. When Cameron affected a similar set of beliefs to Major’s, he was also well ahead in the polls. More recently the 80-year old Michael Heseltine pointed the way ahead with his impressive report on an active industrial strategy. Now Major, retired from politics, charts a credible route towards electoral recovery. How odd that the current generation of Tory leaders is more trapped by the party’s Thatcherite past than those who lived through it as ministers.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)