The hostility that greeted Ed Miliband's ideas about increasing pay epitomises everything that's wrong with British business

Labour leader Ed Miliband delivers a speech on Labour's plans to tackle low pay, at Battersea Power Station in London. Photograph: Stefan Rousseau/PA

Ed Miliband's speech at Battersea power station in London on Tuesday this week attracted a lot of attention. Not least because of the Labour leader's own choice of battleground for the 2015 election, the debate has focused on his ideas about wages: his proposal to raise minimum wages in sectors such as finance, and to provide tax breaks for firms that pay living wages.

The reactions have been predictable. Many people are up in arms against the very idea that the government may "artificially" raise wages through market intervention. Many, including a former adviser to Tony Blair, solemnly warn that this will create unemployment and hurt British companies – or, to be more precise, companies that operate in Britain, as so few are owned by British citizens nowadays.

A typical reaction came from John Cridland, the director general of the CBI, who said in a BBC interview that employers "pay what they can afford to pay, depending on the income they get from the consumers". In this short sentence, Cridland – befitting his status as the spokesman for British business – has unwittingly managed to epitomise what is wrong with British business today.

To begin with, the argument shows the disingenuousness with which many large British companies describe themselves as helpless prisoners of market forces. It implies that the incomes companies get from their consumers are beyond their control, because they cannot charge their customers more than their competitors do.

But many companies do in fact have significant influence over what they charge (known technically as "market power"). It may be because they face little competition, like the railway companies. They may, like the payday loan companies, be dealing with poor customers in desperate situations. It may even be that they actively collude, like the big banks in the Libor scandal, or act in concert, like the energy companies in their recent price rises. Whatever the reason, it is simply not true that these companies have to take whatever customers give them.

So at least companies with market power are perfectly capable of paying their workers more by charging customers more, if they so wanted – except that they don't. Many are busy using the profits from overcharging customers to give big pay rises to their CEOs and give away money to their shareholders. Between 2001 and 2010, the top 86 UK companies included in the Europe 350 index distributed 88% of their profits to shareholders through dividends and share buybacks. Naturally, there is no money left for the workers.

More problematic than this misrepresentation of big business is Cridland's view – shared by many in business, government and media – that British companies cannot "afford" to pay higher wages. The subtext is that British companies have to compete with companies from low-wage countries like China, so British workers should feel lucky they are not paid even less, to match Chinese wages. In this view, whatever causes wages to rise needs to be abolished or at least seriously weakened: trade unions, health and safety regulations (the new whipping boy of the Tory right) or employers' national insurance contributions.

In the short term it may be true that raising wages hurts competitiveness, especially if you are a small company with no market power. However, even in this case the effects of higher wages may be offset by savings from reduced staff turnover and the improved efficiency of happier workers – as Miliband rightly pointed out.

In the long run, however, companies and countries should not be afraid of higher wages. If anything, higher wages are signs of success. They are proof that you are more productive than your competitors, so nations and enterprises should strive to pay higher wages in the long run.

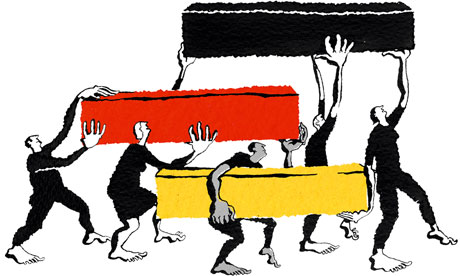

Workers in German car factories are paid about 30 times more than their Chinese counterparts, and twice what their American "competitors" get. Despite that, German car companies more than match their Chinese and even US rivals.

One thing that enables German companies to stay ahead of the game is that Germany as a country has invested heavily in technical education and training, making its workers individually more productive than their foreign counterparts. A more important reason, however, is that German workers benefit from more productive technologies as a result of the investments that German companies have made in advanced machinery and research and development. It is exactly because British companies have not made similar investments that they "cannot afford" to pay their workers good wages.

The low-wage strategy so beloved of the British business elite – or what Miliband called the "race to the bottom" – has no future. If Britain is aiming to compete with China in terms of wages, it will have to lower them by 85%. It is doubtful whether this can be achieved even if it engineers a 30-year recession and installs the harshest military dictatorship. Worse, once it had reduced its wages to the Chinese level, it would have to contend with Vietnam, where wages are one-quarter those of China's. After dealing with Vietnam, Britain would have to face down the Ethiopias and Burundis of this world, with wages one-third that of Vietnam's, or less. Countries like Britain can never win that game.

Does Britain want to go back to Victorian times or, looking forward, become like some Middle East oil states, where a small wealthy minority is served by poorly paid workers with zero-hour contracts and minimal rights? Or does it want to reform its economic system so that its companies and government invest in raising productivity – and thus enable its workers to have decent wages, job security, and well-protected rights?

The choice seems like a no-brainer. Unfortunately, large sections of the British business and political establishment do not see it that way.