Paul Fleckney in The Guardian

Robert Garnham: Insomnia is awful. But on the plus side – only three more sleeps till Christmas.

Dan Antopolski: Centaurs shop at Topman. And Bottomhorse.

Paul Savage: Oregon leads America in both marital infidelity and clinical depression. What a sad state of affairs.

Caroline Mabey: I’m very conflicted by eye tests. I want to get the answers right but I really want to win the glasses.

Athena Kugblenu: Relationships are like mobile phones. You’ll look at your iPhone 5 and think, it used to be a lot quicker to turn this thing on.

Evelyn Mok: My vagina is kind of like Wales. People only visit ironically.

Phil Wang: In the bedroom, my girlfriend really likes it when I wear a suit, because she’s got this kinky fantasy where I have a proper job.

Gráinne Maguire: The Edinburgh fringe is such a bubble. I asked a comedian what they thought about the North Korea nuclear missile crisis and they asked what venue it was on in.

John-Luke Roberts: How did the Village People meet? They obviously led such different lives.

Olaf Falafel: If you’re being chased by a pack of taxidermists, do not play dead.

“Blessed is the nation that doesn’t need heroes" Goethe. “Hero-worship is strongest where there is least regard for human freedom.” Herbert Spencer. "My 80% friend isn't my 20% enemy" Ronald Reagan.

Search This Blog

Wednesday 16 August 2017

Why the Booker prize is bad for writers

Amit Chaudhuri in The Guardian

There are at least two reasons why almost every anglophone novelist feels compelled to get as near the Booker prize as they can. The first is because it looms over them and follows them around in the way Guy de Maupassant said the Eiffel Tower follows you everywhere when you’re in Paris. “To escape the Eiffel Tower,” Maupassant suggested, “you have to go inside it.” Similarly, the main reason for a novelist wanting to win the Booker prize is to no longer be under any obligation to win it, and to be able to get on with their job: writing, and thinking about writing.

Today, there’s little intellectual or material investment in writers: prizes and shortlists are meant to sell books

The other reason is that the Booker prize is most literary publishers’ primary marketing tool. There are relatively few Diana Athills (Athill was VS Naipaul’s editor) and Charles Monteiths (Monteith was William Golding’s) today: publishers who identify, and are loyal to, novelists in the long term because of commitment to literary merit. Publishing houses were once homes to writers; the former gave the latter the necessary leeway to create a body of work. Today there’s little intellectual or material investment in writers: literary prizes and shortlists are meant to sell books, and, although there’s a plethora of them, the Man Booker is the only one that has a real commercial impact.

The idea that a “book of the year” can be assessed annually by a bunch of people – judges who have to read almost a book a day – is absurd, as is the idea that this is any way of honouring a writer. A writer will be judged over time, by their oeuvre, and by readers and other writers who have continued to find new meaning in their writing. The Booker prize is disingenuous not only for excluding certain forms of fiction (short stories and novellas are out of the reckoning), but for not actually considering all the novels published that year, as it asks publishers to nominate a certain number of novels only. What it creates is not so much a form of attention but a midnight ball. The first marketing instrument is the longlist (this year’s was announced last month): 13 novels arrayed like Cinderellas waiting to catch the prince’s eye. (Those not on the longlist find they’ve suddenly turned into maidservants.)

When the shortlist is announced, the enchantment lifts from those among the 13 not on it: they become figments of the imagination. Then the announcement of the winner renders invisible, as if by a wave of the wand, the other shortlisted writers. The princess and the prince are united as if the outcome was always inevitable: at least such is, largely, the obedient response of the press. And the magic dust of the free market gives to the episode the fairytale-like inevitability Karl Popper said history-writing possesses: once history happens in a certain way, it’s unimaginable that any other outcome was possible.

What is astonishing is the acquiescence with which the value system I’ve just described is met with by most writers. Most will feel that it doesn’t speak to why they’re writers at all, but few will discuss this openly. Acceptance is one of the most dismaying political consequences of capitalism. It informs the literary too, and the way publishers and writers “go along” with things. The Booker now has a stranglehold on how people think of, read, and value books in Britain. It has no serious critics. Those who berate its decisions about individual awardees (James Kelman’s prize back in 1994 prompted one judge to say it was “frankly, crap”) ritually add to its allure. After all, the attractiveness of the free market has to do with its perverse system of rewards – unlike socialism, which said everyone should be moderately well off, the free market proposes that anyone can be rich.

The Booker’s randomness celebrates this; it confirms the market’s convulsive metamorphic powers, its ability to confer success unpredictably. In literature, it has redefined terms like “masterpiece” and “classic”.

‘Virginia Woolf didn’t wake up in the morning and think, ‘I wonder if Mrs Dalloway will be longlisted for the Booker?’’ Photograph: George C. Beresford/Getty Images

Few writers, though, display any prickliness. Instead, we end up with the acceptance characteristic of capitalism – which, lately in politics, has led to deep alienation and monstrous alternatives like Donald Trump. I was shocked to run into a novelist who used to regularly rant against the Booker soon after he’d finally won it. It seemed like a part of his personality had gone. Docilely, he was doing the promotional rounds, as if he had been administered a massive sedative. He was robbed of the crusading bitterness that once animated him, and had become a case study of the memory-erasing contentment that capitalism provides.

I’m not saying that the Booker shouldn’t exist. I’m saying that it requires an alternative, and the alternative isn’t another prize. It has to do instead with writers reclaiming agency. The meaning of a writer’s work must be created, and argued for, by writers themselves, and not by some extraneous source of endorsement. No original work is going to be welcomed with open arms by all, and the writer is not doing their job if they don’t make a case for their idea of writing through argumentation, debate, and fervour.

Virginia Woolf didn’t wake up in the morning and think, “I wonder if Mrs Dalloway will be longlisted for the Booker?” She wrote instead her essay, Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown, questioning prevailing forms of valuation in the establishment. Her reformulation of what the novel could be or do, its impact on the reader, and, crucially, the ways in which we value or ignore its possibilities, is as pressing – as political – now as it was then.

DH Lawrence, TS Eliot and Henry James too had to argue, in and outside their creative work, for their idea of the literary, because the question of why literature was important hadn’t been settled. It isn’t settled today.

But, as in other walks of life under capitalism, there has been a loss of initiative among writers: a readiness to let others decide why their work is significant while they busy themselves at literary festivals.

There has been, largely, an abjuring of the critical debates that should, at any given moment, define literature. In British academia, this loss of control over what constitutes value, especially in the humanities, has had its counterpart in what the UK government equivocally calls impact. “Impact” is judged not by gauging the importance of new scholarly work to other scholars, but to the market.

In emollient governmental language, impact is described as “an effect on, change or benefit to the economy, society, culture, public policy or services, health, the environment or quality of life, beyond academia”. As academics have discovered, “beyond academia” is, fundamentally, the market. In other words, the significance of scholarly work will not be judged by the impact it has on the field, but outside it.

The reason why very few question the Booker is, of course, that they will be accused of sour grapes or speaking inappropriately. That’s all right. Woolf was speaking inappropriately when she wrote against the grain of the prevailing decorousness; she suffered from sour grapes, on behalf of her gender and her craft. But her questions needed to be raised, and expressed with pertinence. Only rarely is silence a useful riposte.

There are at least two reasons why almost every anglophone novelist feels compelled to get as near the Booker prize as they can. The first is because it looms over them and follows them around in the way Guy de Maupassant said the Eiffel Tower follows you everywhere when you’re in Paris. “To escape the Eiffel Tower,” Maupassant suggested, “you have to go inside it.” Similarly, the main reason for a novelist wanting to win the Booker prize is to no longer be under any obligation to win it, and to be able to get on with their job: writing, and thinking about writing.

Today, there’s little intellectual or material investment in writers: prizes and shortlists are meant to sell books

The other reason is that the Booker prize is most literary publishers’ primary marketing tool. There are relatively few Diana Athills (Athill was VS Naipaul’s editor) and Charles Monteiths (Monteith was William Golding’s) today: publishers who identify, and are loyal to, novelists in the long term because of commitment to literary merit. Publishing houses were once homes to writers; the former gave the latter the necessary leeway to create a body of work. Today there’s little intellectual or material investment in writers: literary prizes and shortlists are meant to sell books, and, although there’s a plethora of them, the Man Booker is the only one that has a real commercial impact.

The idea that a “book of the year” can be assessed annually by a bunch of people – judges who have to read almost a book a day – is absurd, as is the idea that this is any way of honouring a writer. A writer will be judged over time, by their oeuvre, and by readers and other writers who have continued to find new meaning in their writing. The Booker prize is disingenuous not only for excluding certain forms of fiction (short stories and novellas are out of the reckoning), but for not actually considering all the novels published that year, as it asks publishers to nominate a certain number of novels only. What it creates is not so much a form of attention but a midnight ball. The first marketing instrument is the longlist (this year’s was announced last month): 13 novels arrayed like Cinderellas waiting to catch the prince’s eye. (Those not on the longlist find they’ve suddenly turned into maidservants.)

When the shortlist is announced, the enchantment lifts from those among the 13 not on it: they become figments of the imagination. Then the announcement of the winner renders invisible, as if by a wave of the wand, the other shortlisted writers. The princess and the prince are united as if the outcome was always inevitable: at least such is, largely, the obedient response of the press. And the magic dust of the free market gives to the episode the fairytale-like inevitability Karl Popper said history-writing possesses: once history happens in a certain way, it’s unimaginable that any other outcome was possible.

What is astonishing is the acquiescence with which the value system I’ve just described is met with by most writers. Most will feel that it doesn’t speak to why they’re writers at all, but few will discuss this openly. Acceptance is one of the most dismaying political consequences of capitalism. It informs the literary too, and the way publishers and writers “go along” with things. The Booker now has a stranglehold on how people think of, read, and value books in Britain. It has no serious critics. Those who berate its decisions about individual awardees (James Kelman’s prize back in 1994 prompted one judge to say it was “frankly, crap”) ritually add to its allure. After all, the attractiveness of the free market has to do with its perverse system of rewards – unlike socialism, which said everyone should be moderately well off, the free market proposes that anyone can be rich.

The Booker’s randomness celebrates this; it confirms the market’s convulsive metamorphic powers, its ability to confer success unpredictably. In literature, it has redefined terms like “masterpiece” and “classic”.

‘Virginia Woolf didn’t wake up in the morning and think, ‘I wonder if Mrs Dalloway will be longlisted for the Booker?’’ Photograph: George C. Beresford/Getty Images

Few writers, though, display any prickliness. Instead, we end up with the acceptance characteristic of capitalism – which, lately in politics, has led to deep alienation and monstrous alternatives like Donald Trump. I was shocked to run into a novelist who used to regularly rant against the Booker soon after he’d finally won it. It seemed like a part of his personality had gone. Docilely, he was doing the promotional rounds, as if he had been administered a massive sedative. He was robbed of the crusading bitterness that once animated him, and had become a case study of the memory-erasing contentment that capitalism provides.

I’m not saying that the Booker shouldn’t exist. I’m saying that it requires an alternative, and the alternative isn’t another prize. It has to do instead with writers reclaiming agency. The meaning of a writer’s work must be created, and argued for, by writers themselves, and not by some extraneous source of endorsement. No original work is going to be welcomed with open arms by all, and the writer is not doing their job if they don’t make a case for their idea of writing through argumentation, debate, and fervour.

Virginia Woolf didn’t wake up in the morning and think, “I wonder if Mrs Dalloway will be longlisted for the Booker?” She wrote instead her essay, Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown, questioning prevailing forms of valuation in the establishment. Her reformulation of what the novel could be or do, its impact on the reader, and, crucially, the ways in which we value or ignore its possibilities, is as pressing – as political – now as it was then.

DH Lawrence, TS Eliot and Henry James too had to argue, in and outside their creative work, for their idea of the literary, because the question of why literature was important hadn’t been settled. It isn’t settled today.

But, as in other walks of life under capitalism, there has been a loss of initiative among writers: a readiness to let others decide why their work is significant while they busy themselves at literary festivals.

There has been, largely, an abjuring of the critical debates that should, at any given moment, define literature. In British academia, this loss of control over what constitutes value, especially in the humanities, has had its counterpart in what the UK government equivocally calls impact. “Impact” is judged not by gauging the importance of new scholarly work to other scholars, but to the market.

In emollient governmental language, impact is described as “an effect on, change or benefit to the economy, society, culture, public policy or services, health, the environment or quality of life, beyond academia”. As academics have discovered, “beyond academia” is, fundamentally, the market. In other words, the significance of scholarly work will not be judged by the impact it has on the field, but outside it.

The reason why very few question the Booker is, of course, that they will be accused of sour grapes or speaking inappropriately. That’s all right. Woolf was speaking inappropriately when she wrote against the grain of the prevailing decorousness; she suffered from sour grapes, on behalf of her gender and her craft. But her questions needed to be raised, and expressed with pertinence. Only rarely is silence a useful riposte.

Adani mining giant faces financial fraud claims as it bids for Australian coal loan

by Michael Safi in The Guardian

Exclusive: Allegations by Indian customs of huge sums being siphoned off to tax havens from projects are contained in legal documents but denied by company

Details of the alleged 15bn rupee (US$235m) fraud are contained in an Indian customs intelligence notice obtained by the Guardian, excerpts of which are published for the first time here.

The directorate of revenue intelligence (DRI) file, compiled in 2014, maps out a complex money trail from India through South Korea and Dubai, and eventually to an offshore company in Mauritius allegedly controlled by Vinod Shantilal Adani, the older brother of the billionaire Adani Group chief executive, Gautam Adani.

Vinod Adani is the director of four companies proposing to build a railway line and expand a coal port attached to Queensland’s vast Carmichael mine project.

The proposed mine, which would be Australia’s largest, has been the source of years of intense controversy, legal challenges and protests over its possible environmental impact.

Abbot Point, surrounded by wetlands and coral reefs, is set to become the world’s largest coal port should the proposed Adani expansion go ahead. Photograph: Tom Jefferson / Greenpeace

Expanding the coal port to accommodate the mine will require dredging an estimated 1.1m cubic metres of spoil near the Great Barrier Reef marine park. Coal from the mine will also produce annual emissions equivalent to those of Malaysia or Austria according to one study.

One of the few remaining hurdles for the Adani Group is to raise finance to build the mine as well as a railway line to transport coal from the site to a port at Abbot Point on the Queensland coast.

To finance the railway Adani hopes to persuade the Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility (Naif), an Australian government-backed investment fund, to loan the Adani Group or a related entity about US$700m (A$900m) in public money.

While it awaits the decision on the loan, in Delhi the company is also expecting the judgment of a legal authority appointed under Indian financial crime laws in connection to allegations it siphoned borrowed money overseas.

The Adani Group fully denies the accusations, which it has challenged in submissions to the authority.

The investigation

News of the investigation was first reported in India three years ago, but the full customs intelligence document reveals forensic details of the workings of the alleged fraud which have not been publicly revealed.

The 97-page file accuses the Adani Group of ordering hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of equipment for an electricity project in western India’s Maharashtra state using a front company in Dubai.

To read the pdf click here.

The Dubai company allegedly sold the exact same equipment back to Adani Group-controlled businesses in India at massively inflated prices, in some instances said to be eight times the sale price.

According to the allegations in the file, the effect of these transactions was that the Adani Group spent an average 400% more for the materials. That money was allegedly paid to a company Indian authorities allege was owned through a series of shell companies leading to a Mauritius trust controlled by Vinod Adani.

If true, one effect of the alleged scheme would have been to move vast sums of money from the Adani Group’s domestic accounts into offshore bank accounts where it could no longer be taxed or accounted for.

Because tariffs for using electricity transmission networks are determined partly by what they cost to build, if the DRI’s accusations are correct, the overvaluation of capital goods would have been likely to have led to higher power prices for Indian consumers.

Adani Power company thermal power plant at Mundra, India. Photograph: Sam Panthaky/AFP/Getty Images

A significant proportion of the money the Adani Group allegedly siphoned out of India was provided by taxpayers in the form of loans from the publicly-owned State Bank of India and ICICI, a private bank. There is no suggestion either bank was aware of or involved in any illegal activity.

‘We are cooperating with investigating agencies’

The Adani Group said in a statement to the Guardian on behalf of itself, its subsidiaries, and Vinod Adani that it “strongly denies the allegations of overvaluation”.

Government loan to Adani could be tainted by interference, economists say

“It is a standard procedure for the group to follow international competitive bidding route for major capital expenditures to ensure transparency and competitiveness in the process. All our transactions are always conducted within the framework of extant regulatory guidelines and provisions,” it said.

“The fact that our projects have incurred the lowest cost across central, state and private utility players has gone to establish the robustness of the processes followed by our group.

“It may be noted that Mr Vinod Adani who is the elder brother of Mr Gautam Adani has been a non-resident Indian for about 30 years and has his own established business interests outside India,” the statement said.

“Adani Group is aware of the investigations being conducted by the DRI, and has fully cooperated, and shall continue to cooperate with the investigating agencies.”

The Australian loan

The Adani Group, or a linked entity, has reportedly been granted “conditional approval” for the US$700m (AU$900m) concessional loan from Naif, the Australian government investment fund.

But due to secrecy around the operation of the investment fund, it is not clear whether the loan application discloses the existence of the DRI notice or the ongoing legal proceedings, or whether the applicant is required to do so under the Naif’s anti-money laundering provisions.

Adani Group chairman Gautam Adani meets with Queensland premier Annastacia Palaszczuk in 2016. Photograph: Cameron Laird/AAP

Adani Group did not clarify whether it had informed Naif about the allegations when asked by the Guardian.

Naif’s investment mandate includes a clause preventing it from “act[ing] in a way that is likely to cause damage to the commonwealth government’s reputation, or that of a relevant state or territory government”.

Vinod Adani is currently listed as the sole director of four Singapore-based companies which, through their Australian subsidiaries, are proposing to build the railway line using the government loan. The companies also control a project to expand the Abbot Point port.

All four entities are ultimately owned by Atulya Resources Limited, an Adani-controlled company in the Cayman Islands.

Status of the Indian investigation

The Guardian understands the allegations of over-invoicing have been passed from the DRI to the Enforcement Directorate (ED), an Indian agency tasked with investigating financial crimes.

The Adani Group says the case is currently before a legal authority, the Adjudicating Authority, indicating that Indian officials are pressing either to seize assets they regard as being connected to money laundering or to levy a fine up to three times the sum allegedly siphoned overseas.

The company declined requests to clarify what if any penalty the authorities are seeking, but a spokesman said a decision was expected shortly. “We follow the process of corporate governance and comply with the applicable laws,” he said.

“All our transactions are always conducted within the framework of law. We have already submitted our detailed reply. Adjudication process on the subject is going on and we expect the order in near future.”

The Guardian is publishing excerpts from the DRI file in the interests of ensuring Naif, as well as the public, have access to as much relevant information as possible in assessing whether Adani or linked companies would be suitable recipients of public money.

In a separate case last year, six Adani subsidiaries were listed among 40 other companies being investigated for allegedly running a similar price-inflation scheme. The companies are accused of inflating the price of coal imports from Indonesia to hide profits in overseas tax havens.

The DRI and the ED did not respond to a request to clarify the status of the investigations.

The alleged money trail

India is electricity-starved. More than 240 million Indians – enough people to form the fifth-largest country on Earth – lack access to regular power.

In the early 1990s, to encourage power companies to build electrical infrastructure, the Indian government eliminated import tariffs on technical equipment such as reactors and transformers. Profit margins on these projects increased overnight.

Adani saw the business opportunity. In 2010, the Maharashtra Eastern Grid Power Transmission Company Limited (MEGPTCL), a wholly owned subsidiary of Adani Enterprises, was granted a license to develop two electricity transmission networks in the north-east of the state.

The company used another Adani subsidiary, PMC Projects, to source the equipment it would need to build the networks. In turn, PMC, subcontracted the work to a company in Dubai.

According to the investigators’ report, bank records suggest that that company, Electrogen Infra FZE (EIF), charged significant – and to Indian authorities, suspicious – markups on the equipment it sold to PMC.

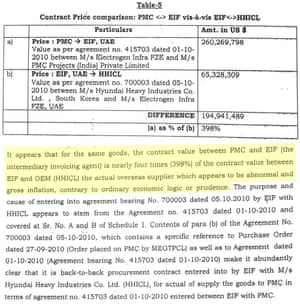

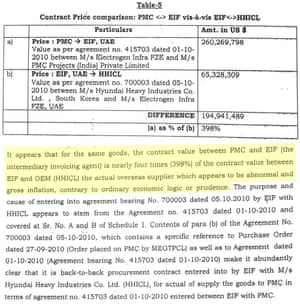

In one of the 57 invoices cited in the report, EIF is alleged to have ordered equipment from Hyundai Heavy Industries in South Korea. Bank records allegedly show the company paid Hyundai about US$65m.

According to the DRI, it sold the same equipment to PMC for about US$260m – a mark-up of nearly 400%.

Extract from page 14-15 of the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence file on Adani Group. Photograph: The Guardian

“[This] appears to be an abnormal and gross inflation, contrary to ordinary economic logic and prudence,” investigators concluded.

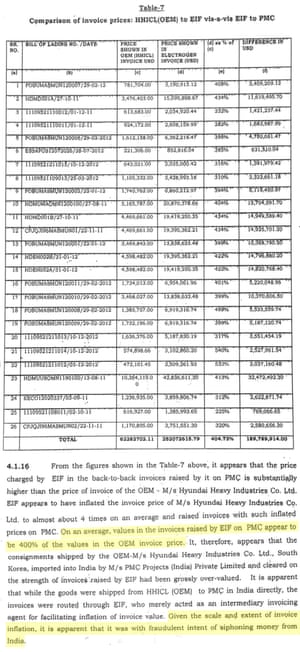

In total, the report alleges EIF made about 26 orders from Hyundai Heavy Industries and sold them onto PMC for an average mark-up of more than 400%, making a profit margin of US$189m.

There is no suggestion Hyundai Heavy Industries or any other supplier was aware of or involved in any illegality.

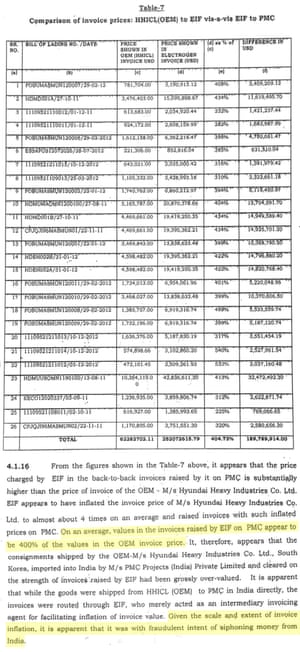

Extract page 19-20 of the DRI file, section 4.1.16. Photograph: The Guardian

EIF allegedly purchased another 25 shipments of equipment from three companies in China. According to the report, these were sold to the Adani Group for an average markup of about 860%.

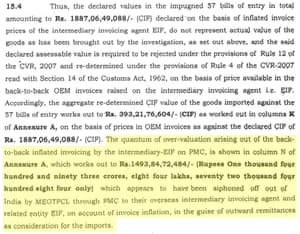

Investigators calculated the total assessable value of the allegedly marked-up invoices to be nearly 15bn rupees.

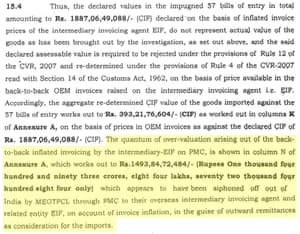

Extract from page 78-79 of the DRI file, section 15.4. Photograph: The Guardian

“Given the scale and extent of invoice inflation, it is apparent that it [was done] with fraudulent intent of siphoning money from India,” the DRI said.

Who controls the companies?

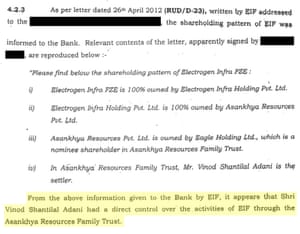

Key to the alleged fraud, according to investigators, is that EIF, the company subcontracted to purchase the equipment from manufacturers in South Korea and China, was directly controlled by the Adani Group and its associates.

Investigators claim EIF was partly staffed by ex-Adani Group employees who had recently left the company.

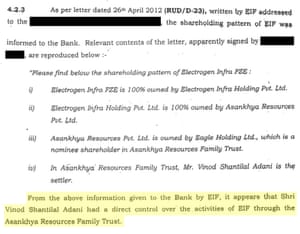

According to a letter from the company to an Indian bank that is cited in the notice, EIF was owned by another company called Electrogen Infra Holding Pvt Ltd (EIH). The trail of ownership eventually leads to a trust based in Mauritius – headed by Vinod Adani.

Extract from page 21-22 of the DRI file, section 4.2.3. Photograph: The Guardian

Investigators concluded: “From the above information given to the bank by EIF, it appears that Vinod Adani had a direct control over the activities of EIF through the Asankhya Resources Family Trust.”

Vinod Adani is also listed as having been the director of EIH between January 2010 and May 2011, though the notice states he told investigators he had no involvement in the day-to-day running of the company.

Investigators also claim to have discovered that an employee of the Adani Group subsidiary PMC had been granted permission by EIF staff to sign multimillion-dollar supply contracts on its behalf.

“All these go to show that there is no distinction between PMC and EIF, they are only working for common interest as part of a large modus-operandi for siphoning off money from India by invoice inflation,” investigators concluded.

The DRI and the ED were both contacted for comment. Attempts were made to contact EIF but the company could not be reached on its listed email or phone number.

Hyundai Heavy Industries did not respond to a request for comment.

It is unclear when the allegations of invoice inflation will be resolved in Delhi other than the Adani spokesman saying that they expected an order “in near future.” In Queensland, Naif’s decision on whether to grant Adani the nearly A$1bn loan is expected by the end of this year.

Exclusive: Allegations by Indian customs of huge sums being siphoned off to tax havens from projects are contained in legal documents but denied by company

Men wearing masks of Australian prime minister Malcolm Turnbull and Adani chairman Gautam Adani protest outside Parliament House in Canberra. Photograph: Lukas Coch/AAP

A global mining giant seeking public funds to develop one of the world’s largest coal mines in Australia has been accused of fraudulently siphoning hundreds of millions of dollars of borrowed money into overseas tax havens.

Indian conglomerate the Adani Group is expecting a legal decision in the “near future” in connection with allegations it inflated invoices for an electricity project in India to shift huge sums of money into offshore bank accounts.

A global mining giant seeking public funds to develop one of the world’s largest coal mines in Australia has been accused of fraudulently siphoning hundreds of millions of dollars of borrowed money into overseas tax havens.

Indian conglomerate the Adani Group is expecting a legal decision in the “near future” in connection with allegations it inflated invoices for an electricity project in India to shift huge sums of money into offshore bank accounts.

Details of the alleged 15bn rupee (US$235m) fraud are contained in an Indian customs intelligence notice obtained by the Guardian, excerpts of which are published for the first time here.

The directorate of revenue intelligence (DRI) file, compiled in 2014, maps out a complex money trail from India through South Korea and Dubai, and eventually to an offshore company in Mauritius allegedly controlled by Vinod Shantilal Adani, the older brother of the billionaire Adani Group chief executive, Gautam Adani.

Vinod Adani is the director of four companies proposing to build a railway line and expand a coal port attached to Queensland’s vast Carmichael mine project.

The proposed mine, which would be Australia’s largest, has been the source of years of intense controversy, legal challenges and protests over its possible environmental impact.

Abbot Point, surrounded by wetlands and coral reefs, is set to become the world’s largest coal port should the proposed Adani expansion go ahead. Photograph: Tom Jefferson / Greenpeace

Expanding the coal port to accommodate the mine will require dredging an estimated 1.1m cubic metres of spoil near the Great Barrier Reef marine park. Coal from the mine will also produce annual emissions equivalent to those of Malaysia or Austria according to one study.

One of the few remaining hurdles for the Adani Group is to raise finance to build the mine as well as a railway line to transport coal from the site to a port at Abbot Point on the Queensland coast.

To finance the railway Adani hopes to persuade the Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility (Naif), an Australian government-backed investment fund, to loan the Adani Group or a related entity about US$700m (A$900m) in public money.

While it awaits the decision on the loan, in Delhi the company is also expecting the judgment of a legal authority appointed under Indian financial crime laws in connection to allegations it siphoned borrowed money overseas.

The Adani Group fully denies the accusations, which it has challenged in submissions to the authority.

The investigation

News of the investigation was first reported in India three years ago, but the full customs intelligence document reveals forensic details of the workings of the alleged fraud which have not been publicly revealed.

The 97-page file accuses the Adani Group of ordering hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of equipment for an electricity project in western India’s Maharashtra state using a front company in Dubai.

To read the pdf click here.

The Dubai company allegedly sold the exact same equipment back to Adani Group-controlled businesses in India at massively inflated prices, in some instances said to be eight times the sale price.

According to the allegations in the file, the effect of these transactions was that the Adani Group spent an average 400% more for the materials. That money was allegedly paid to a company Indian authorities allege was owned through a series of shell companies leading to a Mauritius trust controlled by Vinod Adani.

If true, one effect of the alleged scheme would have been to move vast sums of money from the Adani Group’s domestic accounts into offshore bank accounts where it could no longer be taxed or accounted for.

Because tariffs for using electricity transmission networks are determined partly by what they cost to build, if the DRI’s accusations are correct, the overvaluation of capital goods would have been likely to have led to higher power prices for Indian consumers.

Adani Power company thermal power plant at Mundra, India. Photograph: Sam Panthaky/AFP/Getty Images

A significant proportion of the money the Adani Group allegedly siphoned out of India was provided by taxpayers in the form of loans from the publicly-owned State Bank of India and ICICI, a private bank. There is no suggestion either bank was aware of or involved in any illegal activity.

‘We are cooperating with investigating agencies’

The Adani Group said in a statement to the Guardian on behalf of itself, its subsidiaries, and Vinod Adani that it “strongly denies the allegations of overvaluation”.

Government loan to Adani could be tainted by interference, economists say

“It is a standard procedure for the group to follow international competitive bidding route for major capital expenditures to ensure transparency and competitiveness in the process. All our transactions are always conducted within the framework of extant regulatory guidelines and provisions,” it said.

“The fact that our projects have incurred the lowest cost across central, state and private utility players has gone to establish the robustness of the processes followed by our group.

“It may be noted that Mr Vinod Adani who is the elder brother of Mr Gautam Adani has been a non-resident Indian for about 30 years and has his own established business interests outside India,” the statement said.

“Adani Group is aware of the investigations being conducted by the DRI, and has fully cooperated, and shall continue to cooperate with the investigating agencies.”

The Australian loan

The Adani Group, or a linked entity, has reportedly been granted “conditional approval” for the US$700m (AU$900m) concessional loan from Naif, the Australian government investment fund.

But due to secrecy around the operation of the investment fund, it is not clear whether the loan application discloses the existence of the DRI notice or the ongoing legal proceedings, or whether the applicant is required to do so under the Naif’s anti-money laundering provisions.

Adani Group chairman Gautam Adani meets with Queensland premier Annastacia Palaszczuk in 2016. Photograph: Cameron Laird/AAP

Adani Group did not clarify whether it had informed Naif about the allegations when asked by the Guardian.

Naif’s investment mandate includes a clause preventing it from “act[ing] in a way that is likely to cause damage to the commonwealth government’s reputation, or that of a relevant state or territory government”.

Vinod Adani is currently listed as the sole director of four Singapore-based companies which, through their Australian subsidiaries, are proposing to build the railway line using the government loan. The companies also control a project to expand the Abbot Point port.

All four entities are ultimately owned by Atulya Resources Limited, an Adani-controlled company in the Cayman Islands.

Status of the Indian investigation

The Guardian understands the allegations of over-invoicing have been passed from the DRI to the Enforcement Directorate (ED), an Indian agency tasked with investigating financial crimes.

The Adani Group says the case is currently before a legal authority, the Adjudicating Authority, indicating that Indian officials are pressing either to seize assets they regard as being connected to money laundering or to levy a fine up to three times the sum allegedly siphoned overseas.

The company declined requests to clarify what if any penalty the authorities are seeking, but a spokesman said a decision was expected shortly. “We follow the process of corporate governance and comply with the applicable laws,” he said.

“All our transactions are always conducted within the framework of law. We have already submitted our detailed reply. Adjudication process on the subject is going on and we expect the order in near future.”

The Guardian is publishing excerpts from the DRI file in the interests of ensuring Naif, as well as the public, have access to as much relevant information as possible in assessing whether Adani or linked companies would be suitable recipients of public money.

In a separate case last year, six Adani subsidiaries were listed among 40 other companies being investigated for allegedly running a similar price-inflation scheme. The companies are accused of inflating the price of coal imports from Indonesia to hide profits in overseas tax havens.

The DRI and the ED did not respond to a request to clarify the status of the investigations.

The alleged money trail

India is electricity-starved. More than 240 million Indians – enough people to form the fifth-largest country on Earth – lack access to regular power.

In the early 1990s, to encourage power companies to build electrical infrastructure, the Indian government eliminated import tariffs on technical equipment such as reactors and transformers. Profit margins on these projects increased overnight.

Adani saw the business opportunity. In 2010, the Maharashtra Eastern Grid Power Transmission Company Limited (MEGPTCL), a wholly owned subsidiary of Adani Enterprises, was granted a license to develop two electricity transmission networks in the north-east of the state.

The company used another Adani subsidiary, PMC Projects, to source the equipment it would need to build the networks. In turn, PMC, subcontracted the work to a company in Dubai.

According to the investigators’ report, bank records suggest that that company, Electrogen Infra FZE (EIF), charged significant – and to Indian authorities, suspicious – markups on the equipment it sold to PMC.

In one of the 57 invoices cited in the report, EIF is alleged to have ordered equipment from Hyundai Heavy Industries in South Korea. Bank records allegedly show the company paid Hyundai about US$65m.

According to the DRI, it sold the same equipment to PMC for about US$260m – a mark-up of nearly 400%.

Extract from page 14-15 of the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence file on Adani Group. Photograph: The Guardian

“[This] appears to be an abnormal and gross inflation, contrary to ordinary economic logic and prudence,” investigators concluded.

In total, the report alleges EIF made about 26 orders from Hyundai Heavy Industries and sold them onto PMC for an average mark-up of more than 400%, making a profit margin of US$189m.

There is no suggestion Hyundai Heavy Industries or any other supplier was aware of or involved in any illegality.

Extract page 19-20 of the DRI file, section 4.1.16. Photograph: The Guardian

EIF allegedly purchased another 25 shipments of equipment from three companies in China. According to the report, these were sold to the Adani Group for an average markup of about 860%.

Investigators calculated the total assessable value of the allegedly marked-up invoices to be nearly 15bn rupees.

Extract from page 78-79 of the DRI file, section 15.4. Photograph: The Guardian

“Given the scale and extent of invoice inflation, it is apparent that it [was done] with fraudulent intent of siphoning money from India,” the DRI said.

Who controls the companies?

Key to the alleged fraud, according to investigators, is that EIF, the company subcontracted to purchase the equipment from manufacturers in South Korea and China, was directly controlled by the Adani Group and its associates.

Investigators claim EIF was partly staffed by ex-Adani Group employees who had recently left the company.

According to a letter from the company to an Indian bank that is cited in the notice, EIF was owned by another company called Electrogen Infra Holding Pvt Ltd (EIH). The trail of ownership eventually leads to a trust based in Mauritius – headed by Vinod Adani.

Extract from page 21-22 of the DRI file, section 4.2.3. Photograph: The Guardian

Investigators concluded: “From the above information given to the bank by EIF, it appears that Vinod Adani had a direct control over the activities of EIF through the Asankhya Resources Family Trust.”

Vinod Adani is also listed as having been the director of EIH between January 2010 and May 2011, though the notice states he told investigators he had no involvement in the day-to-day running of the company.

Investigators also claim to have discovered that an employee of the Adani Group subsidiary PMC had been granted permission by EIF staff to sign multimillion-dollar supply contracts on its behalf.

“All these go to show that there is no distinction between PMC and EIF, they are only working for common interest as part of a large modus-operandi for siphoning off money from India by invoice inflation,” investigators concluded.

The DRI and the ED were both contacted for comment. Attempts were made to contact EIF but the company could not be reached on its listed email or phone number.

Hyundai Heavy Industries did not respond to a request for comment.

It is unclear when the allegations of invoice inflation will be resolved in Delhi other than the Adani spokesman saying that they expected an order “in near future.” In Queensland, Naif’s decision on whether to grant Adani the nearly A$1bn loan is expected by the end of this year.

Tuesday 15 August 2017

Monday 14 August 2017

Don't blame addicts for America's opioid crisis. Here are the real culprits

America’s opioid crisis was caused by rapacious pharma companies, politicians who colluded with them and regulators who approved one opioid pill after another

Chris McGreal in The Guardian

‘Opioids killed more than 33,000 Americans in 2015 and the toll was almost certainly higher last year.’

‘Opioids killed more than 33,000 Americans in 2015 and the toll was almost certainly higher last year.’

‘This is an almost uniquely American crisis.’

Opioids killed more than 33,000 Americans in 2015 and the toll was almost certainly higher last year. About half of deaths involved prescription painkillers. Most of those who overdose on heroin or a synthetic opiate, such as fentanyl, first become hooked on legal pills.

This is an almost uniquely American crisis driven in good part by particular American issues from the influence of drug companies over medical policy to a “pill for every ill” culture. Trump’s commission, which called the opioid epidemic “unparalleled”, said the grim reality is that “the amount of opioids prescribed in the US was enough for every American to be medicated around the clock for three weeks”.

The US consumes more than 80% of the global opioid pill production even though it has less than 5% of the world’s population. Over the past 20 years, one federal institution after another lined up behind the drug manufacturers’ false claims of an epidemic of untreated pain in the US. They seem not to have asked why no other country was apparently suffering from such an epidemic or plying opioids to its patients at every opportunity.

With the pharmaceutical lobby’s money keeping Congress on its side, regulations were rewritten to permit physicians to prescribe as many pills as they wanted without censure. Indeed, doctors sometimes found themselves hauled before ethics boards for not supplying enough.

It’s an epidemic because we have a business model for it. Follow the money

Unlike most other countries, the US health system is run as an industry not a service. That gives considerable power to drug manufacturers, medical providers and health insurance companies to influence policy and practices.

Too often, their bottom line is profits not health. Opioid pills are far cheaper and easier than providing other forms of treatment for pain, like physical therapy or psychiatry. As Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia told the Guardian last year: “It’s an epidemic because we have a business model for it. Follow the money. Look at the amount of pills they shipped in to certain parts of our state. It was a business model.”

But the system also gives a lot of power to patients. People coughing up large amounts of money in insurance premiums and co-pays expect results. They are, after all, more customer than patient. Doctors complain of patients who arrive expecting a pill to resolve medical conditions without taking responsibility for their own health by eating better or exercising more.

In particular, the idea has taken hold, pushed by the pharmaceutical industry, that there is a right to be pain free. Other countries pursue strategies to reduce and manage pain, not raise expectations that it can simply be made to disappear. In all of this, regulators became facilitators. The Food and Drug Administration approved one opioid pill after another.

The Food and Drug Administration approved one opioid pill after another.

As late as 2013, by which time the scale of the epidemic was clear, the FDA permitted a powerful opiate, Zohydro, onto the market over the near unanimous objection of its own review committee. It was clear from the hearing that doctors understood the dangers, but the agency appeared to have put commercial considerations first.

US states long ago woke up to the crisis as morgues filled, social services struggled to cope with children orphaned or taken into care, and the epidemic took an economic toll. Police chiefs and local politicians said it was a social crisis not a law and order problem.

Some state legislatures began to curb mass prescribing. All the while they looked to Washington for leadership. They did not get much from Obama or Congress, although legislation approving $1bn on addiction treatment did pass last year. Instead, it was up to pockets of sanity to push back.

Last year, the then director of the Centers for Disease Control, Tom Frieden, made his mark with guidelines urging doctors not to prescribe opioids as a first step for chronic or routine pain, although even that got political pushback in Congress where the power of the pharmaceutical lobby is not greatly diminished.

There are also signs of a shift in the FDA after it pressured a manufacturer into withdrawing an opioid drug, Opana, that should never have been on sale in the first place. It was initially withdrawn in the 1970s, but the FDA permitted it back on to the market in 2006 after the rules for testing drugs were changed. At the time, many accused the pharmaceutical companies of paying to have them rewritten.

Trump’s opioid commission offered hope that the epidemic would finally get the attention it needs. It made a series of sensible if limited recommendations: more mental health treatment people with a substance abuse disorder and more effective forms of rehab.

Trump finally got around to saying that the epidemic is a national emergency on Thursday after he was criticised for ignoring his own commission’s recommendation to do so. But he reinforced the idea that the victims are to blame with an offhand reference to LSD.

Real leadership is still absent – and that won’t displease the pharmaceutical companies at all.

Chris McGreal in The Guardian

‘Opioids killed more than 33,000 Americans in 2015 and the toll was almost certainly higher last year.’

‘Opioids killed more than 33,000 Americans in 2015 and the toll was almost certainly higher last year.’

Of all the people Donald Trump could blame for the opioid epidemic, he chose the victims. After his own commission on the opioid crisis issued an interim report this week, Trump said young people should be told drugs are “No good, really bad for you in every way.”

The president’s exhortation to follow Nancy Reagan’s miserably inadequate advice and Just Say No to drugs is far from useful. The then first lady made not a jot of difference to the crack epidemic in the 1980s. But Trump’s characterisation of the source of the opioid crisis was more disturbing. “The best way to prevent drug addiction and overdose is to prevent people from abusing drugs in the first place,” he said.

That is straight out of the opioid manufacturers’ playbook. Facing a raft of lawsuits and a threat to their profits, pharmaceutical companies are pushing the line that the epidemic stems not from the wholesale prescribing of powerful painkillers - essentially heroin in pill form - but their misuse by some of those who then become addicted.

The amount of opioids prescribed in the US was enough for every American to be medicated 24/7 for three weeks”

In court filings, drug companies are smearing the estimated two million people hooked on their products as criminals to blame for their own addiction. Some of those in its grip break the law by buying drugs on the black market or switch to heroin. But too often that addiction began by following the advice of a doctor who, in turn, was following the drug manufacturers instructions.

Trump made no mention of this or reining in the mass prescribing underpinning the epidemic. Instead he played to the abuse narrative when he painted the crisis as a law and order issue, and criticised Barack Obama for scaling back drug prosecutions and lowering sentences.

But as the president’s own commission noted, this is not an epidemic caused by those caught in its grasp. “We have an enormous problem that is often not beginning on street corners; it is starting in doctor’s offices and hospitals in every state in our nation,” it said.

The president’s exhortation to follow Nancy Reagan’s miserably inadequate advice and Just Say No to drugs is far from useful. The then first lady made not a jot of difference to the crack epidemic in the 1980s. But Trump’s characterisation of the source of the opioid crisis was more disturbing. “The best way to prevent drug addiction and overdose is to prevent people from abusing drugs in the first place,” he said.

That is straight out of the opioid manufacturers’ playbook. Facing a raft of lawsuits and a threat to their profits, pharmaceutical companies are pushing the line that the epidemic stems not from the wholesale prescribing of powerful painkillers - essentially heroin in pill form - but their misuse by some of those who then become addicted.

The amount of opioids prescribed in the US was enough for every American to be medicated 24/7 for three weeks”

In court filings, drug companies are smearing the estimated two million people hooked on their products as criminals to blame for their own addiction. Some of those in its grip break the law by buying drugs on the black market or switch to heroin. But too often that addiction began by following the advice of a doctor who, in turn, was following the drug manufacturers instructions.

Trump made no mention of this or reining in the mass prescribing underpinning the epidemic. Instead he played to the abuse narrative when he painted the crisis as a law and order issue, and criticised Barack Obama for scaling back drug prosecutions and lowering sentences.

But as the president’s own commission noted, this is not an epidemic caused by those caught in its grasp. “We have an enormous problem that is often not beginning on street corners; it is starting in doctor’s offices and hospitals in every state in our nation,” it said.

‘This is an almost uniquely American crisis.’

Opioids killed more than 33,000 Americans in 2015 and the toll was almost certainly higher last year. About half of deaths involved prescription painkillers. Most of those who overdose on heroin or a synthetic opiate, such as fentanyl, first become hooked on legal pills.

This is an almost uniquely American crisis driven in good part by particular American issues from the influence of drug companies over medical policy to a “pill for every ill” culture. Trump’s commission, which called the opioid epidemic “unparalleled”, said the grim reality is that “the amount of opioids prescribed in the US was enough for every American to be medicated around the clock for three weeks”.

The US consumes more than 80% of the global opioid pill production even though it has less than 5% of the world’s population. Over the past 20 years, one federal institution after another lined up behind the drug manufacturers’ false claims of an epidemic of untreated pain in the US. They seem not to have asked why no other country was apparently suffering from such an epidemic or plying opioids to its patients at every opportunity.

With the pharmaceutical lobby’s money keeping Congress on its side, regulations were rewritten to permit physicians to prescribe as many pills as they wanted without censure. Indeed, doctors sometimes found themselves hauled before ethics boards for not supplying enough.

It’s an epidemic because we have a business model for it. Follow the money

Unlike most other countries, the US health system is run as an industry not a service. That gives considerable power to drug manufacturers, medical providers and health insurance companies to influence policy and practices.

Too often, their bottom line is profits not health. Opioid pills are far cheaper and easier than providing other forms of treatment for pain, like physical therapy or psychiatry. As Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia told the Guardian last year: “It’s an epidemic because we have a business model for it. Follow the money. Look at the amount of pills they shipped in to certain parts of our state. It was a business model.”

But the system also gives a lot of power to patients. People coughing up large amounts of money in insurance premiums and co-pays expect results. They are, after all, more customer than patient. Doctors complain of patients who arrive expecting a pill to resolve medical conditions without taking responsibility for their own health by eating better or exercising more.

In particular, the idea has taken hold, pushed by the pharmaceutical industry, that there is a right to be pain free. Other countries pursue strategies to reduce and manage pain, not raise expectations that it can simply be made to disappear. In all of this, regulators became facilitators. The Food and Drug Administration approved one opioid pill after another.

The Food and Drug Administration approved one opioid pill after another.

As late as 2013, by which time the scale of the epidemic was clear, the FDA permitted a powerful opiate, Zohydro, onto the market over the near unanimous objection of its own review committee. It was clear from the hearing that doctors understood the dangers, but the agency appeared to have put commercial considerations first.

US states long ago woke up to the crisis as morgues filled, social services struggled to cope with children orphaned or taken into care, and the epidemic took an economic toll. Police chiefs and local politicians said it was a social crisis not a law and order problem.

Some state legislatures began to curb mass prescribing. All the while they looked to Washington for leadership. They did not get much from Obama or Congress, although legislation approving $1bn on addiction treatment did pass last year. Instead, it was up to pockets of sanity to push back.

Last year, the then director of the Centers for Disease Control, Tom Frieden, made his mark with guidelines urging doctors not to prescribe opioids as a first step for chronic or routine pain, although even that got political pushback in Congress where the power of the pharmaceutical lobby is not greatly diminished.

There are also signs of a shift in the FDA after it pressured a manufacturer into withdrawing an opioid drug, Opana, that should never have been on sale in the first place. It was initially withdrawn in the 1970s, but the FDA permitted it back on to the market in 2006 after the rules for testing drugs were changed. At the time, many accused the pharmaceutical companies of paying to have them rewritten.

Trump’s opioid commission offered hope that the epidemic would finally get the attention it needs. It made a series of sensible if limited recommendations: more mental health treatment people with a substance abuse disorder and more effective forms of rehab.

Trump finally got around to saying that the epidemic is a national emergency on Thursday after he was criticised for ignoring his own commission’s recommendation to do so. But he reinforced the idea that the victims are to blame with an offhand reference to LSD.

Real leadership is still absent – and that won’t displease the pharmaceutical companies at all.

Friday 11 August 2017

The west is gripped by Venezuela’s problems. Why does it ignore Brazil’s?

Reporters ask Jeremy Corbyn if he will condemn Nicolás Maduro. But the undemocratic abuses of Michel Temer aren’t flashy enough for the news cycle

Julia Blunck in The Guardian

Julia Blunck in The Guardian

‘Brazil has carried on as most stories about Latin America do: unnoticed and uncommented on.’ Riot police monitor protests against the government of Michel Temer in Brasilia, May 2017. Photograph: Evaristo Sa/AFP/Getty Images

Venezuela is the question on everyone’s lips. Rather, Venezuela is the question on reporters’ lips whenever they see Jeremy Corbyn: will he condemn the president, Nicolás Maduro? What is his position on Venezuela, and how does it affect his plans for Britain? The actual problems of Venezuela – a complex country with a long history that does not start with the previous president Hugo Chávez and certainly not with Jeremy Corbyn – are largely ignored or pushed aside. This is nothing new: most of the time, Latin America’s debates are seen through western lenses.

Venezuela is the question on everyone’s lips. Rather, Venezuela is the question on reporters’ lips whenever they see Jeremy Corbyn: will he condemn the president, Nicolás Maduro? What is his position on Venezuela, and how does it affect his plans for Britain? The actual problems of Venezuela – a complex country with a long history that does not start with the previous president Hugo Chávez and certainly not with Jeremy Corbyn – are largely ignored or pushed aside. This is nothing new: most of the time, Latin America’s debates are seen through western lenses.

Of course, the situation in Venezuela is deplorable and worrying. But it’s easy to see that concern about Maduro’s undemocratic abuses don’t necessarily come from actual concern for the welfare of Venezuelan people.

Nearby neighbour Brazil has not been analysed or debated at length, even as it demonstrates similar problems. The country’s president, Michel Temer, recently escaped measures that would see him put to trial in the supreme court by getting congress to vote them down. The case against Temer was not a flimsy or partisan one: there was a mountain of evidence, including recordings of him openly debating kickbacks with corrupt businessman Joesley Batista. That a president put into power under circumstances that could be, at best, described as dodgy, manages to remain in power by buying favours from Congress, even as he passes the harshest austerity measures in the world should be enough to raise a few eyebrows internationally. But that has not happened, and Brazil has carried on as most stories about Latin America do: unnoticed and uncommented on.

Part of this discrepancy is of course the bias toward what is flashy. Stories about sordid Congress deals are not that interesting to foreign audiences, and even many exhausted and demoralised Brazilians felt this was simply another addition to a long list of humiliations that began in 2015 when the economy started to sink.

Meanwhile, Venezuela has human conflict, the thing that produces exciting photography and think-pieces, sparks debate and crucially, draws clicks. There’s only so much attention to be gained talking about Temer’s undermining of democracy as it happens without noise, through chicanery and articulation by Brazil’s traditional power: the “Bible, beef and bullets” caucuses in Congress. Venezuela’s situation, however, is urgent, with tanks on the streets and opposition arrests.

Yet there is a subtext to why Brazil’s democracy is not as interesting, and why even Temer’s introduction of the military on to Rio de Janeiro’s streets to address a crime wave has prompted little response. Temer’s rule is one of hard capitalism and an ever-shrinking state. He has established a ceiling on public spending, slashed workers rights, and imposed a hard reform of retirement age.

Temer’s rise to power came as it became clear to big business that his predecessor, Dilma Rousseff, would not go far with austerity. They financed and stimulated protests – largely by rightly angry middle-class Brazilians at what they saw as widespread corruption – while Congress blocked Rousseff’s bills or sabotaged her agenda in other ways.

Latin American suffering is being played out as a proxy for debates in the UK

While Temer did not seize power through a violent coup, and the alliance between Rousseff’s Workers’ party and his notoriously dishonest and chronically double-crossing party was a largely self-inflicted wound, it bears remembering that Rousseff was ousted on a technicality so that Temer could solve the economy’s woes by making “difficult decisions”, a platform for which he had no electoral mandate.

And yet the economy continues to sink, as the unemployment rate soars to 13%. That narrative isn’t very convenient, though, and nobody is interested in making Brazil the representative case of how capitalism is an undemocratic system doomed to fail. And that is quite right: capitalism cannot be exclusively defined by Brazilian failures. The same should be true of socialism in Venezuela.

Somehow, though, the conversation about Venezuela is actually a conversation about something else. Latin American suffering is being played out as a proxy for debates in the UK. As the rightwing media claim, Jeremy Corbyn might not care very much about the thousands going hungry by Maduro’s hand – maybe he too thinks it is simply a consequence of American meddling – but it’s hard to believe that the British right is sincerely committed to the region’s stability and democracy. There has been very little said about Temer.

The failures of Temer do not, and should not be used to, excuse Maduro’s. Nor should we equate the two men in brutality. Yet, if you live in Brazil where public servants are teargassed for not being paid for five months, where indigenous rights activists and others are killed by rich farmers in unprecedented numbers, where several states declare bankruptcy because of a crash in oil prices, where the army is called upon to tackle protesters, you may wonder when your situation will be worth debating.

The answer is whenever it becomes politically convenient. In the end, British commentators and politicians on both the left and right aren’t just opportunistic when it comes to Latin American suffering, they are glad when it happens: it proves their point, whatever that may be. Our lives are just a detail.

Nearby neighbour Brazil has not been analysed or debated at length, even as it demonstrates similar problems. The country’s president, Michel Temer, recently escaped measures that would see him put to trial in the supreme court by getting congress to vote them down. The case against Temer was not a flimsy or partisan one: there was a mountain of evidence, including recordings of him openly debating kickbacks with corrupt businessman Joesley Batista. That a president put into power under circumstances that could be, at best, described as dodgy, manages to remain in power by buying favours from Congress, even as he passes the harshest austerity measures in the world should be enough to raise a few eyebrows internationally. But that has not happened, and Brazil has carried on as most stories about Latin America do: unnoticed and uncommented on.

Part of this discrepancy is of course the bias toward what is flashy. Stories about sordid Congress deals are not that interesting to foreign audiences, and even many exhausted and demoralised Brazilians felt this was simply another addition to a long list of humiliations that began in 2015 when the economy started to sink.

Meanwhile, Venezuela has human conflict, the thing that produces exciting photography and think-pieces, sparks debate and crucially, draws clicks. There’s only so much attention to be gained talking about Temer’s undermining of democracy as it happens without noise, through chicanery and articulation by Brazil’s traditional power: the “Bible, beef and bullets” caucuses in Congress. Venezuela’s situation, however, is urgent, with tanks on the streets and opposition arrests.

Yet there is a subtext to why Brazil’s democracy is not as interesting, and why even Temer’s introduction of the military on to Rio de Janeiro’s streets to address a crime wave has prompted little response. Temer’s rule is one of hard capitalism and an ever-shrinking state. He has established a ceiling on public spending, slashed workers rights, and imposed a hard reform of retirement age.

Temer’s rise to power came as it became clear to big business that his predecessor, Dilma Rousseff, would not go far with austerity. They financed and stimulated protests – largely by rightly angry middle-class Brazilians at what they saw as widespread corruption – while Congress blocked Rousseff’s bills or sabotaged her agenda in other ways.

Latin American suffering is being played out as a proxy for debates in the UK

While Temer did not seize power through a violent coup, and the alliance between Rousseff’s Workers’ party and his notoriously dishonest and chronically double-crossing party was a largely self-inflicted wound, it bears remembering that Rousseff was ousted on a technicality so that Temer could solve the economy’s woes by making “difficult decisions”, a platform for which he had no electoral mandate.

And yet the economy continues to sink, as the unemployment rate soars to 13%. That narrative isn’t very convenient, though, and nobody is interested in making Brazil the representative case of how capitalism is an undemocratic system doomed to fail. And that is quite right: capitalism cannot be exclusively defined by Brazilian failures. The same should be true of socialism in Venezuela.

Somehow, though, the conversation about Venezuela is actually a conversation about something else. Latin American suffering is being played out as a proxy for debates in the UK. As the rightwing media claim, Jeremy Corbyn might not care very much about the thousands going hungry by Maduro’s hand – maybe he too thinks it is simply a consequence of American meddling – but it’s hard to believe that the British right is sincerely committed to the region’s stability and democracy. There has been very little said about Temer.

The failures of Temer do not, and should not be used to, excuse Maduro’s. Nor should we equate the two men in brutality. Yet, if you live in Brazil where public servants are teargassed for not being paid for five months, where indigenous rights activists and others are killed by rich farmers in unprecedented numbers, where several states declare bankruptcy because of a crash in oil prices, where the army is called upon to tackle protesters, you may wonder when your situation will be worth debating.

The answer is whenever it becomes politically convenient. In the end, British commentators and politicians on both the left and right aren’t just opportunistic when it comes to Latin American suffering, they are glad when it happens: it proves their point, whatever that may be. Our lives are just a detail.

Thursday 10 August 2017

Prime Minister Corbyn would face his own very British coup

The left underestimates the establishment backlash there would be if Corbyn were to reach No 10. They need to be ready

Owen Jones in The Guardian

‘In the 1970s, plots against Harold Wilson’s Labour government abounded.’ Photograph: Popperfoto/Getty Images

‘In the 1970s, plots against Harold Wilson’s Labour government abounded.’ Photograph: Popperfoto/Getty Images

As the Sunday Times political editor Tim Shipman put it to me, Theresa May is clinging on “because the Tories are genuinely fearful of a Corbyn government to a degree that goes far beyond usual opposition to Labour”. This panic is shared by other centres of economic and media power. It’s not simply Labour’s policy prospectus they fear. Three decades of neoliberalism – which promotes lower taxes on top earners and big business, privatisation, deregulation and weakened unions – has left them high on triumphalism. They find the prospect of even the most modest challenge to this order intolerable.

And unlike, say, the Attlee government, Labour’s leaders believe that political and social change cannot simply happen in parliament: people must be mobilised in their communities and workplaces to transform the social order. That, frankly, terrifies elite circles. Labour’s opposition to US dominance and a reorientation of Britain’s foreign policy is also viewed as simply unacceptable.

Here are threats to a Labour government to consider. First, undercover police officers. I’ve interviewed women who had relationships with undercover police officers with fake identities. They were climate change activists: the police had recruited individuals willing to sacrifice years of their lives and violate women to keep tabs on the environmental and direct action movements. If they were keeping tabs on small groups of activists, what of a movement with a genuine chance of assuming political power? Then there is the role of the civil service. Thatcherism transformed the attitudes of Britain’s state bureaucracy, particularly in the Treasury: the principles of free-market economics are treated by many senior civil servants as objective facts of life. One former Labour minister told me how, in the late 1990s, civil servants “informed” them that the Human Rights Act forbade controls on private rents. Those officials went on to propose benefit cuts that the Tories would later implement.

Every drop in the pound, every fall in the stock exchange will be hailed as a sign of economic chaos and ruin

Civil servants will tell Labour ministers that their policies are unworkable and must be watered down or discarded. Rather than blocking proposals, they will simply try to postpone them, hold never-ending reviews, call for limited trials – and then hope they are forgotten about. It will require savvy, streetfighting ministers to drive their agenda through.

Finally, those media outlets that cheered on Brexit and accused remainers of hysteria about the consequences, from day one of a Labour government will portray Britain as being in a state of chaos. Every drop in the pound, every fall in the stock exchange will be hailed as a sign of economic chaos and ruin. Demands for U-turns and a moderated agenda will become increasingly vociferous and backed by certain Labour MPs. The hope will be to disorientate, disillusion and divide Labour’s base.

All of these challenges can be overcome, but only by a formidable and permanently mobilised movement. An enthusiastic and inspired grassroots has already succeeded in depriving the Tories of their majority. It will play a critical role if Labour wins. International solidarity – particularly with the US and European left – will prove essential. Such a government will depend on a movement that constantly campaigns in local communities and workplaces. And yes, this is a column that will be dismissed as a tinfoil hat conspiracy. The British establishment has no interest in allowing a government that challenges its very existence to prove a success. These are the people in power whoever is in office, and they will bitterly resist any attempt to redistribute their wealth and influence. Better prepare, then – because an epic struggle for Britain’s future beckons.

Owen Jones in The Guardian

‘The British establishment has no interest in allowing a government that challenges its very existence to prove a success.’ Photograph: Justin Tallis/AFP/Getty Images

‘Do you really think the British state would just stand back and let Jeremy Corbyn be prime minister?” This was recently put to me by a prominent Labour figure, and must now be considered. Happily for me – as a Corbyn supporter who ended up fearing the project faced doom – this long-marginalised backbencher has a solid chance of entering No 10. If he makes it – and yes, the Tories are determined to cling on indefinitely to prevent it from happening – the establishment will wage a war of attrition in a determined effort to subvert his policy agenda and bring his government down.

You are probably imagining me hunched over my computer with a tinfoil hat. So consider this: there is a precedent for conspiracies against an elected British government, it is not so long ago, and it was waged against an administration that represented a significantly smaller threat to the existing order than that offered by Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour.

In the 1970s, plots against Harold Wilson’s Labour government abounded. The likes of Sir James Goldsmith and Lord Lucan believed Britain was in the grip of a leftwing conspiracy; while General Sir Walter Walker, the former commander of allied forces in northern Europe, was among those wanting to form anti-communist private armies. A plot, in which it is likely former intelligence officers and serving military officers were involved, went like this: Heathrow, the BBC and Buckingham Palace would be seized, Lord Mountbatten would be made interim prime minister, and the crown would publicly back such a regime to restore order. At the time, Wilson and his own private secretary were convinced about such a plot culminating in their arrest along with the rest of the cabinet. In Spycatcher, ex-MI5 assistant director Peter Wright openly wrote about a MI5-CIA plot against Wilson.

No, I do not believe a military coup against a Corbyn is plausible, although in 2015, a senior serving general did suggest “people would use whatever means possible, fair or foul”, including a “mutiny”, to block his defence plans. But there will be a determined operation to stop Corbyn ever becoming prime minister. The plots against Wilson were intertwined with cold war politics, and an establishment fear that Britain could defect from the western alliance. In the 1980s, the former Labour minister Chris Mullin wrote the novel A Very British Coup, inspired by the plots against Wilson, which explored an establishment campaign of destabilisation against a leftwing government. Mullin believes “MI5 has been cleared of dead wood” who would drive such plots. Maybe.

There is currently a plot to create a new “centrist” party that would secure a derisory vote share but potentially split the vote enough to keep the Tories in power. In an election campaign, the Tories will struggle with attack lines: “coalition of chaos” is now null and void, and the vitriol of the “get Corbyn” onslaught backfired. But expect a hysterical campaign of fear centred around warnings of economic Armageddon and corporate titans threatening to flee Britain’s shores.

‘Do you really think the British state would just stand back and let Jeremy Corbyn be prime minister?” This was recently put to me by a prominent Labour figure, and must now be considered. Happily for me – as a Corbyn supporter who ended up fearing the project faced doom – this long-marginalised backbencher has a solid chance of entering No 10. If he makes it – and yes, the Tories are determined to cling on indefinitely to prevent it from happening – the establishment will wage a war of attrition in a determined effort to subvert his policy agenda and bring his government down.

You are probably imagining me hunched over my computer with a tinfoil hat. So consider this: there is a precedent for conspiracies against an elected British government, it is not so long ago, and it was waged against an administration that represented a significantly smaller threat to the existing order than that offered by Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour.