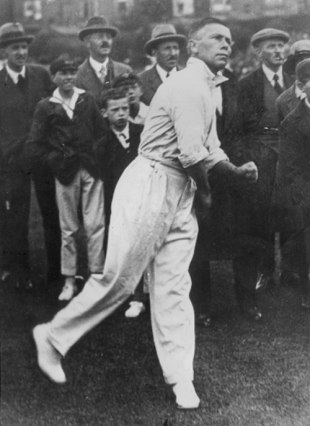

Will Rhodes on Good Length for a bowler

A good length is the shortest length where a batsman is obliged to play forward.

The Right Speed is when a batsman beaten by flight does not have the time to play a second shot.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label spinner. Show all posts

Showing posts with label spinner. Show all posts

Sunday, 25 November 2012

Monday, 29 October 2012

A good cricket book

10 for 66 and All That

by Arthur Mailey

by Arthur Mailey

| |||

Related Links

Players/Officials: Sir Neville Cardus | Jack Fingleton | Lord Harris | Lord Hawke | Sir Pelham Warner

| |||

Suresh Menon: Today the most prized cricketer might be the one in coloured clothing who hits a ball into the dinner basket of a spectator near third man while intending to clear the fielder at midwicket. But not so long ago, it was the "character" who was the most popular. Of one such, Neville Cardus wrote: "The most fascinating cricketer I have known was the Australian [legspinner] Arthur Mailey, an artist in every part of his nature."

The writer and the cricketer were firm friends; both emerged from slums (though thousands of kilometres apart), both taught themselves to write well, each had a personal manner of demonstrating he had climbed out of the past to walk among kings and prime ministers. Cardus wrote on classical music, while Mailey threw champagne parties.

Mailey once said, "I'd rather spin the ball and be hit for four than bowl a batsman out by a straight one." And on another occasion, "If ever I bowl a maiden over, it is not my fault but the batsman's."

Yet the line he is best known for is the one he wrote in his autobiography, 10 for 66 and All That. He had just dismissed his great hero Victor Trumper, stumped off a googly, and the batsman walked back, pausing only to tell the young bowler, "It was too good for me." Mailey captured that moment thus: "There was no triumph in me as I watched the receding figure. I felt like a boy who had killed a dove." This most glorious of lines in all cricketing literature has, in recent years, had doubts cast upon its authenticity. Yet character is revealed as much by what a man has said as by what he would have said. If it is not factual, it is still truthful, and that's what matters.

Mailey, the only Australian to have claimed nine wickets in a Test innings, was an accomplished cartoonist, and his cartoons, which tell of a time and a place, enrich his autobiography. Even if it were merely a well-written story of an unusual life, 10 for 66 And All That might still have made the cut among the best books on the game. But it is more, its insights and predictions both startling and original.

And another five

|

Like those who go against the grain by temperament rather than planning, Mailey displayed a combination of authority and empathy that was unique. He was the one Australian who was sympathetic towards Douglas Jardine and Bodyline. What the series did, according to Mailey, was, it changed the face of cricket reporting. "On the next tour of Australia came an army of 'incident-spotters'," he writes, "just in case there were repercussions that were too newsy... it was then we saw a blast of criticism about umpires' decisions, about playing conditions, about the advisability of players having two or three eggs for breakfast, and of fried liver being on the menu... some of us viewed the future of cricket journalism with apprehension."

Mailey was an accomplished painter too. At an exhibition of his works in London, a royal visitor told him he "had not painted the sun convincingly". Mailey's response was: "You see, Your Majesty, in this country I have to paint the sun from memory."

Mailey, who played his last Test in 1926, was 70 when he wrote this book. And there was nothing wrong with the memory then of the man described by Cardus as an "incorrigible romantic".

Thursday, 7 June 2012

Flatter, faster, weaker

Most Indian spinners today are content to bowl wicket to wicket rather than attack batsmen with turn and bounce. The IPL is to blame to a large extent

Aakash Chopra in Cricinfo

June 6, 2012

When Chris Gayle hit Rahul Sharma for five consecutive sixes in an IPL match in April, I found myself wondering not about Gayle's brute strength or his ability to hit sixes at will but the spinner's response to the onslaught. Would he slow it down, bowl a googly or try a big spinner?

Sharma changed his lines and lengths, but didn't significantly change his pace or variations. If anything, he bowled a bit quicker. Since he is believed to have modelled his action on the great Anil Kumble, it's worth deliberating how Kumble would have responded to such a situation. My educated guess tells me Kumble may have bowled a couple of googlies, taken the pace off another two, or tried a flipper, bowling it faster and pitching it short of a good length, so it skidded off the surface and forced Gayle to pull. All this may or may not have changed the outcome but the use of spinner's most potent weapon, deception, would definitely have made a contest of it.

Since Sharma is still cutting his teeth at international cricket, it's unfair to compare him to a man who has taken 600 Test wickets. But I like to believe that Kumble got to that milestone because of his desire to try something new each time, and not that he experimented only because he had a pile of wickets to support him. After all, records don't make men great; great men make records.

Let's take a look at how other spinners who have a realistic chance of playing for India in the next few years have responded in similar situations.

In the IPL, every time a left-hand batsman went after his bowling, Pragyan Ojha responded with yorkers aimed at the batsman's toes. Some missed their mark by a few inches, some were deposited into the stands by the likes of Gayle, and others went wide down the leg side.

Even Harbhajan Singh, despite his considerable experience, was guilty of bowling flat or fast yorkers under pressure.

Would Muttiah Muralitharan and Daniel Vettori have responded differently? Having watched them play in the IPL for the last five years, it's fair to say that both have enough tricks in the bag to not have to resort to bowling flat in these situations. Murali rarely bowls a yorker, for his strength lies in extracting spin off the surface and disguising his doosra. Vettori slows it down, keeps the ball hanging in the air for a fraction longer and changes his line to counter the onslaught.

R Ashwin is perhaps the only Indian fingerspinner willing to flight the ball, but unfortunately he too seems to be falling into the trap of bowling only doosras and carrom balls. He has compromised on a spinner's biggest strength, the ability to turn the ball, and his performance in Test cricket is getting affected by it.

| Few try to get drift in the air or put enough revolutions on the ball to extract spin and bounce off the surface. Most spinners are just slow bowlers who break the monotony of seam bowling | |||

Not surprisingly, legspinners Piyush Chawla and Amit Mishra refrained from bowling yorkers, because leggies struggle to find the blockhole at will. Mishra bowled variations in the latter part of the tournament, but Chawla wasn't too inclined to turn the ball away from the right-handers.

While it's a given that the best fast bowlers in the IPL will be overseas players, it's a worry if the best spinners are not Indian. But it's not just the IPL; there are no good spinners on India's domestic circuit either. Few try to get drift in the air or put enough revolutions on the ball to extract spin and bounce off the surface. Most spinners are just slow bowlers who break the monotony of seam bowling.

As young batsmen we were told to spend quality time honing our skills to defend against the turning ball. It was imperative to transfer the weight at just the right time, keep the bottom hand loose always, and play close to the body. To succeed in first-class cricket you had to have a solid defence and the ability to hit the turning ball along the ground.

We practised these by playing with a tennis ball from a short distance. Even then, hours of training weren't enough every time, because spinners like Bharati Vij, Venkatapathy Raju, Sunil Joshi, Kanwaljit Singh and others would use the SG Test ball to their advantage and extract both drift and spin. They would rarely bowl flat and fast, because even a batsman's fiercest assault could be countered by deception.

Turning the ball a bit more than expected to get bat-pad dismissals, beating the batsman in the drift and forcing him to edge it to slip, or exploiting poor weight transfer by getting the batsman caught at short cover or midwicket were regular modes of dismissals. As a batsman, it was imperative to look for the shiny side even when facing spinners, for that helped you read the direction of the drift and the arm balls.

Today, even talking about all this makes me feel nostalgic because I can't name a single spinner in the domestic circuit who uses these skills. I also don't see batsmen spending hours to get their forward defence watertight against spin. The only thing a modern batsman does is place the bat in front of the front pad to avoid lbw decisions. Most spinners, not looking to extract any turn, try to bowl wicket to wicket, expecting to get leg-before decisions in case the batsman misses the line. Fielders at short leg and silly point are of ornamental value, except on rank turners. This is a sorry state of affairs for a country that boasted many fine spinners.

The deterioration in the quality of spin started about a decade ago, but the IPL has aggravated it. Anyone willing to practise the traditional craft of spin bowling is routinely overlooked by the IPL talent scouts. The temptation of making it into an IPL team is so huge that compromising flight and spin for accuracy and flatter trajectories seems a small price to pay.

While there were many young left-arm spinners on show this IPL season, not one of them bowled with a high-arm action or looked suitable for the longer version of the game. The moment you bowl with a round-arm action and lower your arm, you cease to get bounce off the surface. It also doesn't allow you to put enough revolutions on the ball to get spin off the surface, which is why such bowlers rely heavily on dusty pitches to spin the ball.

It is a lovely sight to watch batsmen struggling to dig out accurate yorkers, but only if the practitioner operating 22 yards away is a fast bowler, not a spinner.

Wednesday, 30 May 2012

How to Adapt to the 4 Types of Attacking Batsmen

From Pitch Vision Academy

http://www.pitchvision.com/how-to-adapt-to-the-4-types-of-attacking-batsmen

Sometimes your bowling spell doesn't go to plan and the batsman is the one on the attack.

Now it's time to adapt our plan to take into account how and where the batsman is hitting the ball.

One option is to move a fielder or two around to cut off his favourite shot, and try and force him to play a shot he isn't so comfortable with. This will often lead to his dismissal.

Another option is to leave the field as it is. Instead back ourselves to dismiss him by adjusting our bowling strategy itself. Here we look at how to counter-attack four types of aggressive batsman:

1. The batsman who is playing aggressively against the spin

The batter is cutting and cover driving the off spinner, or playing across the line against the leg spinner. Here the percentages are with you, so simply keep spinning the ball as hard as possible to try and beat the bat. Probe for an error. Work in some simple variations and find the hole. Keep spinning the ball as much as possible. Eventually, he will make a mistake.

2. The batsman who is consistently playing with the spin

Here the batter is cutting and cover driving the leg spinner, and working the off spinner into midwicket. He has now left himself vulnerable to the ball moving in the opposite direction. The killer blow will come from beating the opposite side of the bat to the direction of turn. To do this, use either a googly to bowl him through the gate or an arm-ball to find the leading edge.

3. The batsman who is attacking with cross batted shots

Sweeping and pulling in the order of the day with this batter. The wrong ‘un or a big spinning stock ball will have little effect against the cross batted shots. In this case, we need to vary our flight - especially using topspin and backspin - to get the ball over or underneath the horizontal swing of the bat. A backspinner will get us a bowled or LBW. A top spinner will result in a top-edge or a nick behind.

4. The batsman who is charging down the track or slogging.

These two can be dealt with in the same way. You're looking for a stumping or an aerial shot resulting in a catch. Changes of pace are key here, so that batsman is unable to time his shot. Top spin will also create extra dip and bounce and make the ball more likely to go in the air. If you can make the ball move away from the batsman, you will also have a better chance of a stumping.

About the author: AB has been bowling left arm spin in club cricket since 1995. He currently plays Saturday league cricket and several evening games a week. He is a qualified coach, and his experiences playing and coaching baseball often gives him a different insight into cricket.

The ART of Flight to deceive the batsmen

What spin bowler hasn't heard these clichés in his cricketing career?

"Toss it up" the young spin bowler is so often told. "You've got to flight the ball, give it some air, and get it above the batsman's eye line".

The problem is that experience soon teaches that simply lobbing the ball up in the air does not suddenly make a competent batsman turn into a tail end bunny. Whilst the advice may be well meaning, it completely misses the point. Flight is about deception. There is nothing deceptive about simply bowling the same ball but slower and with a higher trajectory.

The art of spin bowling is the art of deceiving the batsman as

to what the ball will do. This comes in two parts: we are able to

confuse him when the ball pitches by making it turn. It might

turn a small amount, it might turn a large amount or it might turn the

other direction entirely.

We are also able to use the same set of techniques to deceive him as to where the ball will pitch in the first place.

This is flight: the art of deceiving the batsman as to the exact location where the ball will pitch.

Well, first and foremost we use the same technique we use to make the ball turn: by spinning it hard. In the case of flighting the ball, this primarily means using topspin and backspin.

These make use of the Magnus effect to change the trajectory of the ball as it travels towards the batsman.

Using the two in combination makes batsman completely clueless as to whether to play forward or back to any given delivery.

http://www.pitchvision.com/how-to-adapt-to-the-4-types-of-attacking-batsmen

Sometimes your bowling spell doesn't go to plan and the batsman is the one on the attack.

Now it's time to adapt our plan to take into account how and where the batsman is hitting the ball.

One option is to move a fielder or two around to cut off his favourite shot, and try and force him to play a shot he isn't so comfortable with. This will often lead to his dismissal.

Another option is to leave the field as it is. Instead back ourselves to dismiss him by adjusting our bowling strategy itself. Here we look at how to counter-attack four types of aggressive batsman:

1. The batsman who is playing aggressively against the spin

The batter is cutting and cover driving the off spinner, or playing across the line against the leg spinner. Here the percentages are with you, so simply keep spinning the ball as hard as possible to try and beat the bat. Probe for an error. Work in some simple variations and find the hole. Keep spinning the ball as much as possible. Eventually, he will make a mistake.

2. The batsman who is consistently playing with the spin

Here the batter is cutting and cover driving the leg spinner, and working the off spinner into midwicket. He has now left himself vulnerable to the ball moving in the opposite direction. The killer blow will come from beating the opposite side of the bat to the direction of turn. To do this, use either a googly to bowl him through the gate or an arm-ball to find the leading edge.

3. The batsman who is attacking with cross batted shots

Sweeping and pulling in the order of the day with this batter. The wrong ‘un or a big spinning stock ball will have little effect against the cross batted shots. In this case, we need to vary our flight - especially using topspin and backspin - to get the ball over or underneath the horizontal swing of the bat. A backspinner will get us a bowled or LBW. A top spinner will result in a top-edge or a nick behind.

4. The batsman who is charging down the track or slogging.

These two can be dealt with in the same way. You're looking for a stumping or an aerial shot resulting in a catch. Changes of pace are key here, so that batsman is unable to time his shot. Top spin will also create extra dip and bounce and make the ball more likely to go in the air. If you can make the ball move away from the batsman, you will also have a better chance of a stumping.

About the author: AB has been bowling left arm spin in club cricket since 1995. He currently plays Saturday league cricket and several evening games a week. He is a qualified coach, and his experiences playing and coaching baseball often gives him a different insight into cricket.

The ART of Flight to deceive the batsmen

What spin bowler hasn't heard these clichés in his cricketing career?

"Toss it up" the young spin bowler is so often told. "You've got to flight the ball, give it some air, and get it above the batsman's eye line".

The problem is that experience soon teaches that simply lobbing the ball up in the air does not suddenly make a competent batsman turn into a tail end bunny. Whilst the advice may be well meaning, it completely misses the point. Flight is about deception. There is nothing deceptive about simply bowling the same ball but slower and with a higher trajectory.

So what is flight then?

We are also able to use the same set of techniques to deceive him as to where the ball will pitch in the first place.

This is flight: the art of deceiving the batsman as to the exact location where the ball will pitch.

How do we do this?

Well, first and foremost we use the same technique we use to make the ball turn: by spinning it hard. In the case of flighting the ball, this primarily means using topspin and backspin.

These make use of the Magnus effect to change the trajectory of the ball as it travels towards the batsman.

- Top spin will make the ball drop more quickly and land further away from the batsman than expected. Imagine a tennis player playing a top spin shot with his racquet, hitting over the top of the ball. You can apply this same spin on a cricket ball. How you do it will depend on whether you are a finger spinner or wrist spinner but the effect of spinning “over the top” is the same.

- Back spin will make the ball carry further and land closer to the batsman. Our tennis player would slice underneath the ball to make the shot. Again your method for doing this will vary but think ‘slicing under the ball’ to create the effect.

Using the two in combination makes batsman completely clueless as to whether to play forward or back to any given delivery.

Thursday, 10 May 2012

The Five Best Ever Spinners according to Ashley Mallett

Ashley Mallett in Cricinfo

Shane Warne's

star illuminated the cricket firmament, inspiring generations with the

majesty of his art. When Warne reigned supreme on the Test stage, you'd

see kids in the park and in the nets trying to emulate him. They got

the saunter right, but what they didn't see was Warne's amazing

strength, drive and energy through the crease. Watching him, it all

looked so easy. They would emulate his approach, release the ball, and

more times than not watch it disappear out of the park. There was a

general lack of understanding about energy and drive through the crease.

Warne turned up just when we all thought legspin had gone the way of the

dinosaurs, who were bounced out when Earth failed to duck a hail of

meteors. Sir Donald Bradman said Warne's legspin was the best thing to

happen to Australian cricket in more than 30 years. I, along with

thousands of television viewers, watched transfixed as Warne weaved his

magic. Poor Mike Gatting, poor, hapless Daryll Cullinan.

I was in the South African dressing room when Warne destroyed them with 6 for 34 in their second innings at the SCG in 1998. And we all remember the time he got seven wickets for 50-odd at the MCG

against West Indies, getting Richie Richardson with a flipper. Before

that grand performance, which sparked his career, the camera focused on

Warne in the field, and Bill Lawry said on air: "Now there's a young man

who won't get much bowling today." The Phantom was right: Warne bowled

23 overs; not a lot of work for a slow bowler, but that was all he had

to get seven wickets.

Warne's genius got him 708 wickets in 145 Tests. His physical skills were matched by an incredibly strong mind. He was frequently in a lot of controversy off the cricket field, but he managed to focus totally on his cricket when it mattered on the field of play. As with Don Bradman and Garry Sobers, he was a cricketing phenomenon.

The Indian offspinner Erapalli Prasanna

was a small, rotund chap, with little hands and stubby fingers. Not the

size of hand you'd think would be able to give a cricket ball

tremendous purchase.

Pras, as he was affectionately called, bounced up to the wicket and got

very side-on. He was short, so he tended to toss the ball up, and he

spun it so hard it hummed. Unlike the majority of spinners, he could

entice you forward with tantalising flight or force you back, and often

got a batsman trapped on the crease. His changes of pace weren't always

as subtle as Warne's, but Pras broke the rhythm of batsmen better than

any spinner I've seen - especially with that quicker ball, which

perplexed the best players of spin bowling in his era.

He possessed a mesmerising quality in that he seemed to have the ball on

a string. You'd play forward and find yourself way short of where you

expected the ball to pitch. In Madras once, I thought I'd take him on

and advanced down the wicket only, to my horror, find that Pras had

pulled hard on the "string" and I was miles short of where the ball

pitched. I turned, expecting to see Farokh Engineer remove the bails,

only to see the ball, having hit a pothole, climb over the keeper's head

for four byes.

Pras was one of the few spinners to worry the life out of Ian Chappell,

for he could trap him on the crease or lure him forward at will. Doug

Walters, on the other hand, played the offspinners better than most -

perhaps because his bat came down at an angle and the more you spun it,

the more likely it was to hit the middle of his bat.

In 49 Tests Prasanna took 189 wickets at an average of 30.38. For a

spinner who played a lot on the turning tracks of India, his average is

fairly tall, but Pras was a wicket-taker and he took risks, inviting the

batsman to hit him into the outfield. He always believed that if the

batsman was taking him on and trying to hit him while he was spinning

hard, dipping and curving the ball, he would have the final word.

For his tremendous performances in Australia in 1967-68, I place Prasanna if not above, at least on par with another genius offspinner, the Sri Lankan wizard Muttiah Muralitharan.

Murali's Test figures beggar belief - 133 matches for 800 wickets at

22.72, with 67 bags of five wickets or more (though, for some reason, he

didn't shine in Australia).

He operated from very wide on the crease - which would inhibit the

ordinary offie - but got so much work on the ball and a tremendous

breadth of turn that he got away with bowling from that huge angle. At

times he operated from round the wicket to get an away drift. Murali had

the doosra, which fooled most batsmen, although the smart ones knew

that his offbreak was almost certainly going to be a fair way outside

the line of off stump to a right-hander and that the doosra would come

on a much straighter line.

| His changes of pace weren't always as subtle as Warne's, but Prasanna broke the rhythm of batsmen better than any spinner I've seen | |||

Saqlain Mushtaq lost his way over the doosra, the delivery he created,

because he ended up bowling everything on too straight a line, and thus

his offbreak became far less effective at the end of the career than it

was when he began.

As with Saqlain and Warne, Murali made good use of his front foot. When

any spinner gets his full body weight over his braced front leg at the

point of release, he achieves maximum revolutions.

As a youngster Murali attended the famous St Anthony's College in Kandy,

and every Sunday morning he trained under the tutelage of Sunil

Fernando. Ruwan Kalpage, who also trained under Fernando at the time,

and is the current Sri Lankan fielding coach, maintains that Murali

always had the same action that he took into big cricket.

As with Warne, when bowling, Murali had an extraordinary area of danger,

as big an area as your average dinner table. The likes of Ashley Giles,

say, on the other hand, who didn't spin the ball very hard, needed to

be super accurate, for their area of danger was about as a big as a

dinner plate in contrast.

The key to spin bowling is not where the ball lands but how the ball

arrives to the batsman. As with Warne and Prasanna, when Murali bowled,

the ball came with a whirring noise and after striking the pitch rose

with venom. Throughout his career and beyond there has been that nagging

doubt about the legitimacy of Murali's action, but the ICC has cleared

him and that is why I place him among the best five spinners I've seen.

My No. 4 is Derek Underwood,

the England left-arm bowler, who has to be categorised as a spinner,

although he operated at about slow-medium and cut the ball rather than

spun it in the conventional left-arm orthodox manner. On good wickets

Lock was a superior bowler to Underwood, but on underprepared or

rain-affected wickets, the man from Kent was lethal.

He had a lengthy approach, a brisk ten or so paces, with a rather

old-fashioned duck-like gait, and a hunter's attitude, along with a keen

eye for a batsman's weakness. In August 1968, Underwood demolished Bill

Lawry's Australian team on the last day of the fifth Test.

Heavy rain gave the Australians hope of escaping with a draw and so

winning the series 1-0. But Underwood swooped after tea and cut them

down, taking 7 for 50.

|

|||

A week later he joined John Inverarity, Greg Chappell (who had just

completed a season with Somerset) and me on Frank Russell's Cricketers

Club of London tour of West Germany. We stayed in a British Army camp

just outside the old city of Mönchengladbach. We played a cricket match

against the army, using an artificial pitch and welded steel uprights

doubled for stumps.

A huge West Indian came to the crease and we pleaded with Deadly to

"throw one up". Having faced him over five Tests in England, where his

slower ball was about the speed of Basil D'Oliveira's medium-pacers, we

were keen to see how the batsman - any batsman - would react, when

Underwood gave the ball some air. He eventually did. As the ball left

his hand we could see a hint of a smile on the batsman's face. The ball

disappeared and was never retrieved. Underwood's face was a flush of red

as he let the next ball go, and what a clang it made as it hit those

steel uprights, while the West Indian's bat was still on the downswing!

Apart from his destructive ability on bad or rain-affected tracks,

Underwood was also a brilliant foil for the fast bowlers on hard

wickets. He kept things tight as a drum when bowing in tandem with John

Snow during Ray Illingworth's successful 1970-71 Ashes campaign Down

Under.

My fifth choice might surprise some for I've gone for Graeme Swann, the best of the modern torchbearers for spin bowling.

I first saw him with Gareth Batty and Monty Panesar, fellow spin

hopefuls, in Adelaide in the early 2000s. Swann had energy through the

crease, he spun hard, and he tried to get people out. At that time some

of the coaches leaned towards Panesar and I couldn't understand it, for

Swann wasn't just a fine offspinner, he could bat when he put his mind

to it, and he was an exceptional slip fieldsman. In comparison Panesar

did not seem to have the same resolve or the cricketing nous.

When he was finally recognised as a top-flight spinner, Swann proved

himself straightaway. He was 29 years old when he played his first Test,

against India in 2008-09, and in the four-odd years since, he has

played 41 Tests, taking 182 wickets at 27.97. Swann doesn't have the

doosra, but he does have the square-spinner, which looks like an offie

but skids on straight, and he can beat either side of the right-hander's

bat.

There's a cheerful chirpiness about him that may annoy his opponents,

but that is part of his make-up, just as the aggression of a Bill

O'Reilly, or the cold stare of Warne, helped them dominate batsmen.

Statistically Swann's record so far compares well with Jim Laker's (193

wickets at 21.24 from 46 Tests) and Tony Lock (49 Tests - 174 wickets at

25.58 with 9 five-wicket hauls).

There are lots of good spinners who I have had to omit, including Lock,

Laker, Abdul Qadir, Lance Gibbs, Richie Benaud, Daniel Vettori, Anil

Kumble, Sonny Ramadhin, Intikhab Alam, John Emburey, Pat Pocock, Ray

Illingworth, Fred Titmus and Stuart MacGill. But the five I did pick -

Warne, Prasanna, Murali, Underwood and Swann - would do well against any

batsmen in any era.

Sunday, 24 July 2011

A spinner's flight plan

The great spinners visualised their wickets and deceived the batsmen in the air. But why are today's bowling coaches almost always fast men?

Ashley Mallett in Cricinfo

July 24, 2011

In my first over in Test cricket, to Colin Cowdrey at The Oval in August 1968, I appealed for lbw decisions for the first four balls. The fifth ball was the decider. Cowdrey went well back and the ball cannoned into his pads halfway up middle stump. Umpire Charlie Elliott raised his index finger, and "Kipper" touched the peak of his England cap and said to me, "Well bowled, master."

In hindsight Cowdrey was a pretty good wicket, given that he had conquered the spin of Sonny Ramadhin and Alf Valentine at a time when I was trying to track down an ice-cold Paddle Pop in Perth.

Test cricket is the ultimate challenge for the spin bowler. Sadly Twenty20s and ODIs bring mug spinners to the fore. They skip through their overs and bowl "dot" balls, which their legion of hangers-on believe to be something akin to heaven. Test spinners are all about getting people out. After all, the best way to cut the run rate is to take wickets.

Before getting into big cricket I felt the need to have a coaching session with Clarrie Grimmett. I was 21, living in Perth, and Clarrie, a sprightly 76, was based in Adelaide. To my mind a spinner cannot be doing things all that brilliantly if he thinks he is a pretty good bowler but doesn't get many wickets. That was my lot, and I sought Clarrie's advice. Two days in the train from Perth to Adelaide, then a short bus ride to the suburb of Firle, found Clarrie at home. He was up the top of an ancient pepper tree.

There he had hung a ball in a stocking. He handed me a Jack Hobbs-autographed bat, and having dismissed my protestations that I wanted to learn spin bowling, not batting, he said with a broad grin: "Well, son, there was a youngster I taught to play the square cut on the voyage to England in 1930 and… Don Bradman was a fast learner."

Clarrie swung one ball towards me and I met it in the middle of his bat. We then went to the nets. Clarrie had a full-sized turf wicket in his backyard. He wandered to the batting end. He wore no protective equipment - no box, no pads or gloves. Just his Jack Hobbs bat. "Bowl up, son," he cried.

My first ball met the middle of his bat. He called me down the track. "Son," he said, "Give up bowling and become a batsman… I could play you blindfolded."

As it happened I had a handkerchief in my pocket. He put that over his horn-rimmed glasses and my second ball met the middle of his bat. When he had stopped laughing he proceeded to give me the best possible lesson on spin bowling. He talked about spinning on a trajectory just above the eye line of the batsman.

Eighteen months later I was playing a Test match in India. The Nawab of Pataudi was facing, and while he was not smashing my bowling all over the park, he was clearly in control. I had to find a way to arrest the situation, so I thought of Grimmett and the necessity of getting the ball to dip acutely from just above the eye line.

It worked. The dipping flight fooled him to the extent that he wasn't sure exactly where the ball would bounce. Pataudi pushed forward in hope rather than conviction, and within four balls Ian Chappell had grabbed another bat-pad chance at forward short leg.

A spinner needs a plan to get wickets at the top level. Even a bad plan is better than no plan at all, but it is not about reinventing the wheel.

Grimmett had many a plan. He told me that he often saw the image of a batsman he was about to dismiss in his mind's eye. When the wicket fell, he was nonchalant, for this was the action replay. Nowadays visualisation is an official part of cricket coaching.

The key to spin bowling is how the ball arrives. If the ball is spun hard and the bowler gets lots of energy up and over his braced front leg, he will achieve a dipping flight path that starts just above the eye line and drops quickly.

Grimmett firmly believed, as does Shane Warne, that a batsman had to be deceived in the air. Warne's strategy at the start of a spell was to bowl his fiercely spun stock legbreak with subtle changes of pace. Similarly my idea was to stay in the attack. There is nothing worse for a bowler than to go for 10 or 12 runs in his first over. Psychologically you are then playing catch-up to make your figures look reasonable.

| If a spinner doesn't plan he doesn't change his pace and thus does not break the rhythm of the batsman. It is crucial to a Test spin bowler's success that he attacks with subtle changes of pace | |||

As an offspinner I found if my off-side field was in order the rest fell into place. My basic plan against a right-hander was to have the ball arriving in a dangerous manner: spin hard and drive up and over the braced front leg. And I wanted to lure the batsman into trying to hit to the off side, against the spin, to look at the huge gap between point and my very straight short cover. When a batsman hit against the spin and was done in flight, the spin would take the ball to the on side - a potential catch to bat-pad or short midwicket. Sometimes this plan doesn't work - the batsman might be clean-bowled, or if the ball skipped on straight, caught at slip, or it would cannon into his front pad for no result. (Also a leg spinner's plan to a left hand batter)

If a spinner doesn't plan he doesn't change his pace and thus does not break the rhythm of the batsman. It is crucial to a Test spin bowler's success that he attacks with subtle changes of pace.

I had played 10 Test matches and taken 46 wickets when Bob Simpson, the former Australia opening batsman and Test captain, sidled up to me and said: "You need a straight one."

I eyeballed Bob and said that some of my offbreaks went dead straight and "they don't pick them". He went on to say that I needed a ball that, to all intent and purpose, looked as if it would turn from the off but would skip off straight. I could "bowl" what they call a doosra today, but when I played, offspinners did not have ICC carte blanche to throw the ball. I felt it was wrong to throw, so I discarded the whole thing.

In Tests a batsman is challenged by pace and spin. My aim was to take 100 Test wickets in 20 Tests. But I got there in my 23rd - the same as Shane Warne, Glenn McGrath and Garth McKenzie - after which circumstances changed. Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson joined forces, and man, you tried to grab a wicket anyhow while those two were on the hunt. My next 15 Tests brought little in way of wickets, but my experience helped me in a coaching sense. I knew how unloved and untried spinners felt.

Somehow the cricket world brought forth a bunch of national coaches who didn't know the difference between an offbreak and a toothpick. Some were celebrated ones, like South Africa's Bob Woolmer. His idea of combating spin was ludicrous. He had blokes trying to hit sixes against Shane Warne's legspin. As splendid as he was against any opposition, no wonder Warne excelled against Woolmer-coached sides.

It is amazing that all national sides pick ex-fast bowlers as their bowling coaches. At least in England, Andy Flower, easily the best coach in world cricket, recognises the role of the spin coach. Mushtaq Ahmed, the former Pakistan legspinner, teams with David Saker, the fast-bowling coach, to help the England bowlers.

For years Australia have floundered in the spin department. Troy Cooley, the bowling coach, is a fast-bowling man, not one for spin. Australia has suffered; a lot of the blame can be attributed to the stupid stuff going on at the so-called Centre of Excellence in Brisbane.

Australia have had three great spinners: Grimmett, Bill O'Reilly and Warne. If Grimmett had played 145 Tests, the same as Warne, he would have taken 870 wickets. Different eras, of course, but you get the idea of how good Grimmett was. However, the best offie I ever saw - by a mile - was the little Indian Erapalli Prasanna. Now there was a bowler.

Offspinner Ashley Mallett played 38 Tests for Australia

© ESPN EMEA Ltd.

Thursday, 21 July 2011

Test cricket - a primal contest

The primal contest

The game's essential match-up, of batsman against bowler, finds its best expression in Test cricket

Cricket is a contest between bat and ball, a struggle that reaches its highest form in the Test arena. In most games the players are attempting the same skills and the result depends on the quality of the execution. Boxers and tennis players land the same sorts of blows, play the same type of shots. In cricket, as in baseball, the teams have the same aim but the process involves a primeval battle between batsman and bowler.

It is a confrontation between prey and predator, collector and hunter, reason and fury. Both sides strive with every power at their disposal to emerge triumphant. At first the bowler presses for a quick kill, for he knows his opponent is at his most vulnerable before he has settled. If the batsman survives his period of reconnoitering, his opponent might change his strategy, play a waiting game, set a trap, seek an opening, probe for weakness, mental or technical, or else invite his rival to reach too far. Victory alone matters and it can be attained by means slow or swift, fair or foul.

For his part the batsman strives to calm his nerves and become accustomed to light and pitch and ball. He tries to take his time and to give no hint of shakiness, even as the elephants dance in his belly. Most likely he will endeavour to play a tried and trusted game honed over the years. Every innings is different, though, and no bowler is quite the same, so the willow wielder needs to have his wits about him.

The attack might include a tearaway, a crafty veteran, an innocent-looking swinger, a mean fingerspinner, and a wristy one, capable of giving both ball and bottle a fearful rip. By and large all of them will fulfill their caricature. At the lower levels the aged chap is the one to watch. Bowlers learn a thing or two as they go along. Hence the saying, "Never underestimate a grey-haired bowler."

Not that a fellow ever learns that lesson. One of the delights of cricket is that even experienced and supposedly intelligent players keep making the same mistakes and keep berating themselves with the same curses. Pitted against a touring Australian side not so long ago, I managed to survive the opening onslaught and then licked my lips as the ball was thrown to a creaking purveyor of slow curlers. Too late I realised that the accursed pensioner was not as guileless as he seemed, and that his deliveries were not so much easy meat as poisoned chalice. By then the trudge back to that place of eternal wisdom and endless regret, the dressing room, was well underway.

Ordinarily the batsman will begin to widen his range of shots once established at the crease. It is not always a conscious decision. As often as not, the change of tempo happens of its own accord. Confidence, a tiring attack and frustration can combine to hasten the flow of runs. Unless the field is pushed back, innings advance in fits and starts. Placement, too, is less common than supposed. Batsmen might manoeuvre the ball into a gap or loft into empty spaces, but piercing the field with a full-blooded shot usually depends as much on luck as skill.

Of course batsmen and bowlers sometimes switch sides. Then the batsman becomes the predator, attacking from the outset and so changing the course of the contest. Even opening batsmen have become audacious. Previously the movement of the ball and a wider insecurity caused by Depressions and wars dampened ardour. Charlie Macartney, an incorrigible Australian (that might be repetitive), was an exception. By his reckoning an opener ought to dispatch a drive back at the bowler's head at the first opportunity, thereby informing him that he was in for a proper scrap. Nowadays the spread of briefer formats, the dryness of the pitches and the mood of the era encourage early attempts to seize the initiative.

Test cricket provides the opportunity for every player to express his talents to the utmost. Whereas the one-day game, to some degree, dictates terms to those taking part, limiting their overs, reducing their time at the crease, influencing field placements and bowling changes, a five-day match is as liberating as it is daunting.

Unsurprisingly the most compelling exchanges between bat and ball take place in the Test arena. Here the greatest players of the era are given the chance to try their luck against their equivalents, and the freedom to score 200 or a duck, take 10 wickets or concede a stack of runs without reward.

Bowlers, especially, relish the opportunity to prove their worth. At last they can set their own fields anyhow - so long as they don't copy Douglas Jardine - and bowl as many overs as captain and body allow. Inevitably the leading practitioners have produced their best work in this environment, constructing dazzling, tormenting spells that linger as long in the memory as the brilliant innings played by their temporary foes. Along the way they have reminded observers that bowling can be as rewarding as batting, and a lot more destructive.

Every cricket enthusiast will recall occasions when bowlers surpassed themselves. Michael Holding's stint at The Oval in 1976 was unforgettable. At once he was graceful and mesmerising, not so much running to the crease as gliding to it. Head upright, shoulders swaying slightly, toes barely touching the grass, he gathered himself at delivery and without apparent effort sent down thunderbolts that contained the charm of the antelope and the wrath of a vengeful god. Stumps kept toppling over like skittles and shaken batsmen came and went, knowing they had been undone by an irresistible force.

Richard Hadlee's performance in Brisbane was more surgical than stunning. Operating off a seasoned run, summoning formidable expertise, cutting the ball around off a track that helped him a little and others not at all, he worked his way through the local order. Even by his precise standards it was a tour de force. Like so many of the best spells, too, the wicket-taking deliveries were defined not so much by their deadliness as by the company they kept. Superb batsmen were harried and humiliated into error. The Kiwi did not bruise a single body but he damaged many egos.

Wasim Akram's virtuoso display at the MCG stands out because he had the ball upon a string, made it bend both ways at a scintillating pace and left accomplished batsmen gasping and groping. It's hard enough countering a bowler sending them down at 90mph and swinging it in one direction. When they start moving it both ways, it's downright unfair. Wasim streamed to the crease and with a gleam more mischievous than menacing, produced an astonishing spell.

Malcolm Marshall's most remarkable contribution came on a slow pitch at the SCG. West Indies had already won the series, and some suspected that the track had been prepared for the home spinners. Certainly West Indies were below their best. Amongst the flingers only Marshall rose to the challenge. Shortening his run, adjusting his length, he transformed himself from fearsome fast bowler to relentless, precise, probing swinger. And he kept at it for two days, even as the Australians piled on the runs. It was a thrilling, stunning piece of controlled, resourceful, pace bowling.

Among the modern masters, Glenn McGrath and Shane Warne stand apart. McGrath looked like a hillbilly and bowled like a scientist. He was consistent and accurate, controlled and masterful, nagging away, securing extra bounce and movement, relying on skill alone to remove batsmen. He worked his way through an order as a rodent does a hunk of cheese, constantly nibbling, taking it piece by piece. If Lord's, with its inviting slope and disconcerting ridge witnessed his deadliest spells, it was because it suited him better than any other surface. But McGrath's greatness was most clearly revealed in his hat-trick taken in Perth against West Indies. His dismissals of Sherwin Campbell, Brian Lara and Jimmy Adams were notable for the precision of his analysis, the coldness of the execution, and the degree of craft required and revealed in the space of three balls. McGrath's combination included a perfectly pitched outswinger to an opening batsman inclined to hang back, a cutter landing on the sticks that drew a worried response from a gifted left-hander, and a bumper that rose at the shoulder of a tormented captain. Every delivery was inch perfect.

Warne's stature was revealed in his first and final contributions to Ashes series in England. His genius was shown by that very first delivery, to Mike Gatting, even as his character was confirmed by the fact that he dared to try his hardest-spun and least reliable offering. Twelve years later he was back in the old dart and trying to win an Ashes series off his own back. His performance in claiming 40 scalps in that ill-fated campaign stands alongside any contribution from any spinner in the history of the game. Although his powers were in decline, Warne's mind remained sharp, his determination was unwavering and his stamina superb. It was an unyielding, magnificent performance from a sportsman blessed with artistry, audacity, grit and bluff.

Of course many other great bowlers and bowling feats could be mentioned. The sight of Jeff Thomson unleashing another thunderbolt, Bishan Bedi lulling opponents to their doom, Murali spinning the ball at right angles in his early years, Waqar changing games with his sudden sandshoe crushers, Mike Procter in full flight, Derek Underwood landing it on a threepenny, and so many others pass easily into the mists of time.

That bowling has a beauty of its own is proven by these expert practitioners. They were as big a draw card as any batsman. The buzz that went around grounds as Warne marked out his run, the hush as the fast bowler stood at the top of his run, reinforces the point. Test cricket brings out the best in batsmen and bowlers alike, allows the game to reach its highest point. Confrontations between the giants - Lillee and Richards, Marshall and Gavaskar, Warne and Tendulkar - can be as exhilarating and satisfying. Then spectators and players remember what it was that that drew them to the game in the first place, and why they remain somewhat under its spell.

Peter Roebuck is a former captain of Somerset and the author, most recently, of In It to Win It

© ESPN EMEA Ltd.

Thursday, 12 August 2010

Reading the Batsmen

Video footage is well and good, but there are also plenty of clues for bowlers to pick up from their opponents' grips, back-lifts and stances

August 12, 2010

| |||

What if a bowler could read a batsman's mind - predict how a batsman would play before bowling a ball to him or having watched him play? Wouldn't it bolster his chances, give him leeway to plan, and buttress his skill?

Some may call it wishful thinking, others a secret science, but often just looking at the grip with which a batsman holds his bat tells you something about his preferences in terms of shots, and the way he stands may help you place your fielders.

Will a batsman be a good driver of the ball or more comfortable scoring off the back foot? Will he prefer scoring runs through the on side or the off? It's important to observe the finer nuances of a batsman's grip, stance and back-lift to size him up and plan accordingly. While it may seem utterly useless in this day and age of exhaustive analysis based on video footage, which is available to almost all professional teams, observation was one of the tools players relied heavily on in the past, and it continues to be useful.

The grip

Most batsmen playing professional cricket hold the bat correctly with regard to the Vs made by thumbs and forefingers. The top hand is firmer and the V its thumb and forefinger makes opens out towards the outer edge of the bat, while the bottom hand plays only a supporting role.

Most batsmen playing professional cricket hold the bat correctly with regard to the Vs made by thumbs and forefingers. The top hand is firmer and the V its thumb and forefinger makes opens out towards the outer edge of the bat, while the bottom hand plays only a supporting role.

A correct grip allows a proper downswing, which in turn enables a batsman to play the ball with the full face of the bat. The right grip is also imperative if you want to play the entire range of shots.

While the basics remain the same, lots of batsmen do enough with the grip to give some information away. For instance, Sanath Jayasuriya holds the bat close to the bottom of the handle, and Adam Gilchrist higher up. Now the coaching manual recommends that one holds the bat in the middle of the handle, but to say that successful players like these two don't hold the bat correctly would be grossly incorrect. While there are pros and cons to each approach, it all boils down to what suits your game best.

Holding the bat closer to the bottom gives you more control and helps you generate more power at the point of impact. In such cases, since the bottom hand becomes dominant very often, you don't need a high back-lift to hit the ball long and hard. That's why Jayasuriya is ever so good with his short-arm jabs. Such players generally are more comfortable on the back foot, and horizontal bat shots are their bread and butter. The flip side of holding the bat close to the base of the handle is that the arc of the downswing gets radically smaller, which in turn reduces the reach and makes driving off the front foot that much difficult. But some players are exceptions to this rule. Sachin Tendulkar holds the bat close to the bottom of the handle but has managed to overcome the shortcomings with ease.

On the contrary, Gilchrist's batting is built on the extension of the arms, and holding the bat high on the handle compliments the extension. With this grip, the arc of the downswing becomes bigger, and hence increases the reach of the batsman. Lower-order batsmen tend to prefer this grip to enhance their reach. That's how the phrase "using the long handle" was coined. The flip side of such a grip is that you may not have enough control and you have to rely on the downswing to generate power. Players with such grips prefer playing on the front foot and can also be a little circumspect against quick short-pitched bowling. Gilchrist, like Tendulkar, is an exception here.

Then there were those like Javed Miandad, who had a gap between the top and bottom hands. The textbook recommends keeping the hands close to each other on the handle, to ensure that they move in unison. Yet Miandad's grip allowed him to manoeuvre the bowling and milk it for singles, though he possibly sacrificed some fluency in the bargain.

The stance

If the grip on the bat is the first giveaway, the manner in which a batsman stands is the second. While the coaching manual recommends the feet be about a shoulder span apart, lots of batsmen have toyed with different options to suit their game.

If the grip on the bat is the first giveaway, the manner in which a batsman stands is the second. While the coaching manual recommends the feet be about a shoulder span apart, lots of batsmen have toyed with different options to suit their game.

People who stand with their feet too close to each other are often good back-foot players and the ones with wider stances are generally stronger on the front foot. Here, too, there are snags: you lose some balance if both feet are too close, and too wide apart results in lack of foot movement.

A stance that's too side-on or too open-chested also tells you a bit about the strengths and weaknesses of a batsman. While you'd be suspect against inswingers if your stance is too side-on, you'd struggle against away-going deliveries if it is too open. Sachin Tendulkar's is the closest to what would be a perfect stance - though even he tended to lean too much towards the off side when he started.

| The textbook recommends keeping the hands close to each other on the handle, to ensure that they move in unison. Yet Miandad's grip, with hands apart, allowed him to manoeuvre the bowling and milk it for singles | |||

Even the way you take guard can give the bowler a pointer or two. Generally players who ask for a leg-stump guard are good on the off side, for they try to make room by staying beside the line. And the ones who ask for middle stump are good on the leg side, for their endeavour is to whip it through the leg side. It's not a hard-and-fast rule but any information is better than none at all.

If a batsman is falling over, with his head not in line with his toes - which is the case with a lot of batsmen - he will predominantly be an on-side player, but would still be susceptible to sharp, incoming deliveries. Also, the intended ground shots on the leg side will probably travel in the air for a while, and hence positioning a fielder at short midwicket comes in handy. Such a batsman would also be unsure of his off stump and hence might play balls that are meant to be left alone.

The back-lift

The last clues before the ball is finally bowled come from the height of the back-lift and its arc. Ideally the bat should come down from somewhere between the off stump and first slip, to ensure that the bat moves straight in the downswing.

The last clues before the ball is finally bowled come from the height of the back-lift and its arc. Ideally the bat should come down from somewhere between the off stump and first slip, to ensure that the bat moves straight in the downswing.

Players who bring the bat in from wider than second slip, like Rahul Dravid, need to make a loop at the top of the downswing, or else they will find it difficult to negotiate sharp incoming deliveries. Should they fail to make that loop, the bat won't come down straight, which means meeting the ball at an angle instead of straight on.

Batsmen with higher back-lifts find it difficult to deal with changes of pace, because with higher back-lifts it's tougher to pull out of a shot after committing. Also, there's always a possibility they will be late in bringing the bat down to keep yorkers out. Ergo, yorkers and slower ones might just do the trick.

Since players with short back-lifts, like Paul Collingwood and Andrew Symonds, don't have a reasonable downswing, they rely on the pace of the ball to generate power for their shots. They tend to struggle if the ball has no pace on it, so taking the pace off isn't a bad move against them. On the contrary, short back-lifts are almost ideal to keep yorkers out with.

If anyone has to think on his feet in cricket, it is the bowler. For it is he who initiates the action and everyone else reacts to what he delivers. Yet, these days he's the game's underdog, constantly at risk of being on the receiving end, and bound to follow a plan to render himself effective. Since video data isn't available to teams before they reach a certain level, most bowlers rely on observing the finer nuances of their opponents in order to strategise.

Former India opener Aakash Chopra is the author of Beyond the Blues, an account of the 2007-08 Ranji Trophy season. His website is here

© ESPN EMEA Ltd.

Wednesday, 3 February 2010

Leg Spin Q & A from Warne's coach

Terry Jenner

'Dot-ball cricket is hurting spin'

Terry Jenner on the importance of the stock ball, getting the flipper right, why Australia are yet to produce a spinner of Shane Warne's calibre, and more

February 1, 2010

| ||

During practice and in matches I keep trying different ways of spinning the ball. I get wickets but also go for a lot of runs. How do I stick to the basics for the most part? asked Dylan D from China

It is a mental thing. The most important ball is your stock ball: if you are a legspinner it is the legbreak. You bowl it when you need to keep things tight and when you need to take a wicket. By all means work on your variations, but not before you have got reasonable control over your stock ball.

It is a mental thing. The most important ball is your stock ball: if you are a legspinner it is the legbreak. You bowl it when you need to keep things tight and when you need to take a wicket. By all means work on your variations, but not before you have got reasonable control over your stock ball.

At times I get the ball to spin a lot but then there are times when it just does not turn. What do I do? asked Chad Williams from Belgium

The ball doesn't always react the way you want it to. In the 2005 Ashes Test at Lord's, Shane Warne bowled three legbreaks to Ian Bell, who shouldered arms to first two, as they spun a long way towards slip. The third one hit him in front and he was out lbw. He thought it was a variation ball but it was really a legbreak that did not spin.

The ball doesn't always react the way you want it to. In the 2005 Ashes Test at Lord's, Shane Warne bowled three legbreaks to Ian Bell, who shouldered arms to first two, as they spun a long way towards slip. The third one hit him in front and he was out lbw. He thought it was a variation ball but it was really a legbreak that did not spin.

Why can't all legspinners bowl the googly? Why do some of them lose their main delivery when they start bowling the wrong 'un? asked Milind from the USA

Because of the wrist position. When you bowl a googly, the back of your hand faces the batsman. The more you do that, the less likely it is for your wrist or palm to face the batsman when you bowl the legbreak. It just creates a bad habit. Most legspinners love the thought of bowling the googly which the batsman may or may not pick. But the trouble is the more you bowl it, the more your wrist gets into a position where it won't support your legbreak.

------Also read

On Walking - Advice for a Fifteen Year Old

The leggie who was one of us

--------

I know you do not believe in teaching budding offspinners how to bowl the doosra. But what about the away-going delivery as bowled by Erapalli Prasanna? I believe Harbhajan Singh's, and maybe even Jason Krejza's, doosra deliveries are the sort of floaters Prasanna used to bowl? asks Kunal Sharma from Canada

The thing about the doosra is that the people who have bowled it have normally had their actions questioned. Most of the guys don't have the flexibility to bowl that ball. Graeme Swann has shown how excellent an offspinner can be with an orthodox offbreak and an arm ball - a ball that looks like an offbreak but does not spin. Nathan Hauritz got five wickets against Pakistan in Sydney bowling the same way. Just because a delivery reacts different off the pitch does not mean the bowler is bowling the doosra. It can often be just a reaction off the pitch.

I would like to know how to make the ball dip. Also, how does a legspinner understand what is the right pace to bowl at? asks Nipun from Bangladesh

The right pace to bowl at is the pace where you gain your maximum spin. Then you vary your pace from there. But you must understand what pace you need to bowl at. That is very important. Warne gained his maximum spin at around 50mph (80 kph). After that, he got less and less spin. For a young bowler that pace could vary between 35-40mph. So whatever speed it is, be satisfied that you can bowl that ball and gain the maximum spin.

Regarding the dip, it comes from over-spin. When you release the ball, you spin it up and generate a lot of over-spin. For the curve, as opposed to the dip, it is important you align yourself with the target which, say is the middle stump. If you just rotate your wrist 180 degrees, release the ball right to left from you hand, there is a good chance the ball will curve in towards the right-hand batsman. Drop is different from curve.

I have watched your 'Masterclass' videos many times but still find it very difficult to bowl the flipper. I understand the concept of squeezing the ball out, but I haven't been able to grasp the idea of doing it in full motion: the arm movement is anti-clockwise and to "squeeze" the ball out of your fingers is clockwise? asked Akash Sureka from the UK

Again, alignment is very important if you are trying to bowl the flipper. You need to align yourself side-on towards your target, which should be around off stump. Then bowl with your shoulder towards that target, flicking the ball underneath as you release it from your hand. Keeping the seam pretty much upright encourages the ball to curve. Your fingers should be above and below the seam because you are using your thumb, your first and second fingers squeezing the ball underneath your hand. But the bowling shoulder needs to be powerful and also bowling towards the target. There is no anti-clockwise. The hand goes straight towards the target.

How do you think Warne got his amazing confidence, leadership skills and competitive spirit? asked Nadir H from India

I believe he was born with that gift just like he was born with the gift of spin. Warne had a massive heart and showed a lot of courage. You didn't know that the first day you met him. The longer he played, the more certain he became of his own ability and then the competitive spirit came forward.

I once heard Warne's technique should not be imitated by youngsters. Is it because there's pressure on his shoulder or that he doesn't have a run-up, so to speak? asked Nihal Gopinathan from India

This is one question I find annoying because a run-up is only for rhythm. Coaches who encourage people to run in like medium-pacers are not allowing the legspinner to go up and over his front leg. It is important that you bowl over a braced front leg. Warne had eight steps in his approach but walked the last three and had lovely rhythm. People said only Warne was strong enough to bowl that way. I don't think so, because as long as you bowl at your natural pace it is fine. If you are looking for a role model why would you not look at the best in the world? Warne had the five basics of spin: he was side-on; to get side-on, your back foot needs to be parallel to the crease and Warne's was; his front arm started weakly but by the time of release it grew very powerful; he drove his shoulders up and over when he released the ball; and completed his action by rotating 180 degrees. Those basics came naturally to him and were the key to him walking up to the crease and jumping to bowl.

Who do you think is currently the best spinner in the world? asked Yazad from India

Going by current performances, Swann is tough to ignore. He is getting important wickets and helping England win Test matches. I think he has every reason to believe, as he does, he should be very highly rated. I like Danish Kaneria, who probably is the best wrist spinner in the world.

Why has Australia not produced a decent spinner since Warne? Do you think Hauritz, Krejza, etc. have not been given the long rope that Warne got in his early days? asked Vijay from Singapore

People forget that Warne was thrown into the deep end and at one stage had 1 for 228 and his career could have been terminated very early. But faith, patience and others' the belief in his ability helped Shane recoup, along with the enormous talent he had. Before him, we had a lot of guys who were average-to-good legspin bowlers. Probably before Warne, Clarie Grimmett was the best legspinner. Richie Benaud was outstanding and consistent but did not spin big. Warne is an once-in-a-lifetime bowler. When he first played, he did not know how to defend himself. As he got better, he learned how to defend himself. That is how you become a great bowler.

Krejza is still in the mix, and at the moment they are pushing for New South Wales' Steven Smith but he is just a baby. Hauritz has shut the door on the others because he has improved steadily in the last 12 months. He has made improvements to his bowling action, is getting spin and drift and is very much a Test-match bowler.

| ||

Are there any other spin options on the horizon for Australia? asked Allan Pinchen from Australia

One of the difficulties in developing young spinners is the Under-19 competition. Every two years there is an U-19 World Cup. The limited-overs format is not about spin but about containment. When Warne came through the system, they played four-day games. During his formative years he toured England, West Indies and Zimbabwe, bowling in four-day matches. Brad Hogg on the other hand was a ten-over bowler. Between the two World Cups (2003 and 2007) I have no doubt Hogg was the best spinner. But when given the opportunity in the Test side, 10 overs were not good enough. You have to be able to bowl at least 20-25 overs.

Do you think in Twenty20 spinners are at a disadvantage since the ball is always relatively new and hence they don't get enough spin off the pitch? asked Ashish from the USA

Twenty20 is not about spin, even if they say it is. It is really about slow bowling. I watch fast bowlers bowl six slow balls an over. It is about taking the pace off the ball and the same applies to spinners. I watched Harbhajan Singh help India win the 2007 World Cup in South Africa and he was bowling 100kph yorkers wide off the crease. You wonder about the development of the spinner then. I don't think he has been the same bowler since.

With the growing emphasis on the shorter forms of the game, how can any country develop a quality wicket-taking slow bowler? asked John Westover from Australia

That is a great question. In my view we should find ways of getting those young, developing spinners to play longer forms of cricket where they can bowl sustained spells. There are two ways to develop as a spinner: by going to the nets and working on your craft and bowling at targets. Or by experimenting and bowling in matches where you can try the things you tried in the nets. In limited-overs games everyone applauds a dot ball but not the batsman's strokes. To develop as a spinner in the four-day game you have to invite the batsman to play strokes. If the mental approach of all concerned - the coach, captain and team-mates - is to keep it tight, the spinner struggles to develop. We say big bats and short boundaries have created difficulties for a spin bowler but dot-ball cricket has done more damage.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)