The protests in the US are a pivotal moment and people of colour need active allyship writes Nicola Rollock in The Financial Times

A very privileged white man recently told me with an indulgent chuckle how much he enjoyed his privilege. I was not amused. For people of colour, white privilege and power shape our lives, restrict our success and, as we were starkly reminded in recent weeks, can even kill. No matter how well-crafted an organisation’s equality and diversity policy, the claims of “tolerance” or the apparent commitment to “embracing diversity”, whiteness can crush them all — and often does.

People of colour know this. We do not need the empirical evidence to tell us that black women are more likely to die in childbirth or that black boys are more likely to be excluded from school even when engaging in the same disruptive behaviour as their white counterparts. We did not need to wait for a study to tell us that people with “foreign sounding names” have to send 74 per cent more applications than their white counterparts before being called for an interview — even when the qualifications and experience are the same.

Or that young people of colour, in the UK, are more likely to be sentenced to custody than their white peers. We do not need more reviews to tell us we are not progressing in workplaces at the same rate as our white colleagues. We already know. Many of us spend an inordinate amount of time and energy trying to work out how to survive the rules that white people make and benefit from.

While many white people seem to have discovered the horrors of racism as a result of George Floyd’s murder, it would be a mistake to overlook the pervasive racism happening around us every day. For the truth is Floyd’s murder sits at the chilling end of a continuum of racism that many of us have been talking about, shouting and protesting about for decades.

Whiteness — specifically white power — sits at the heart of racism. This is why white people are described as privileged. Privilege does not simply refer to financial or socio-economic status. It means living without the consequences of racism. Stating this is to risk the ire of most white people. They tend to become defensive, angry or deny that racism is a problem, despite the fact they have not experienced an entire life subjected to it.

Then there are the liberal intellectuals who believe they have demonstrated sufficient markers of their anti-racist credentials because they have read a bit of Kimberlé Crenshaw — the academic who coined the term “intersectionality” to describe how different forms of oppression intersect. Or, as we have seen on Twitter, there are those who quote a few lines from Martin Luther King.

Liberal intellectuals will happily make decisions about race in the workplace, argue with people of colour about race, sit on boards or committees or even become race sponsors without doing any work to understand their whiteness and how it has an impact on their assumptions and treatment of racially minoritised groups.

There are, of course, white people who imagine themselves anti-racist while doing little if anything to impact positively on the experiences of people of colour. As the author Marlon James and others have stated, being anti-racist requires action: it is not a passive state of existence.

Becoming aware of whiteness and challenging passivity or denial is an essential component of becoming a white ally. Being an ally means being willing to become the antithesis of everything white people have learnt about being white. Being humble and learning to listen actively are crucial, as a useful short video from the National Union of Students points out. This, and other videos, are easily found on YouTube and are a very accessible way for individuals and teams to go about educating themselves about allyship.

White allies do not pretend the world is living in perfect harmony, nor do they ignore or trivialise race. If the only senior Asian woman is about to leave an organisation where Asian women are under-represented and she is good at her job, white allies will flag these points to senior management and be keen to check whether there is anything that can be done to keep her. White allies are not quiet bystanders to potential or actual racial injustice.

Allyship also means letting go of the assumption that white people get to determine what constitutes racism. This is highlighted by the black lesbian feminist writer and journalist Kesiena Boom, who has written a 100-point guide to how white people can make life less frustrating for people of colour. (Sample point: “Avoid phrases like “But I have a Black friend! I can’t be racist!” You know that’s BS, as well as we do.”)

Active allyship takes effort

Being an ally means seeing race and acknowledging that white people have a racial identity. In practical terms, it means when we talk about gender, acknowledging that white women’s experiences overlap with but are different to those of women of colour. White women may be disadvantaged because of their gender, but they are privileged because of their racial identity. When we talk about social mobility, employment, education, health, policing and even which news is reported and how, race plays a role. Usually it is white people who are shaping the discourse and white people who are making the decisions.

This is evident even when white people promise commitment to racial justice in the workplace. It is usually white people who make the decision about who to appoint, the resources they will be given, what they can say and do. In their book Acting white? Rethinking race in post-racial America, US scholars Devon W Carbado and Mitu Gulati argue that white institutions tend to favour and progress people of colour who are “racially palatable” and who will do little to disrupt organisational norms. Those who are more closely aligned to their racial identity are unlikely to be seen as a fit and are, consequently, less likely to succeed.

Being a white ally takes work. It is a constant process, not a static point one arrives at and can say the job is complete. It is why despite equalities legislation, there remains a need for organisations — many of them small charities operating on tight budgets — such as the Runnymede Trust, StopWatch, InQuest, Race on the Agenda, brap and Equally Ours. Their publications offer useful resources and information about racial justice in the workplace as well as in other sectors.

There is, of course, a dark perversity to white allyship that is not often mentioned in most debates about racial justice. White allyship means divesting from the very histories, structures, systems, assumptions and behaviours that keep white people in positions of power. And, generally, power is to be maintained, not relinquished.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label racism. Show all posts

Showing posts with label racism. Show all posts

Thursday, 4 June 2020

Sunday, 24 May 2020

Wednesday, 9 October 2019

If we can’t call racism by its name, diversity will remain a meaningless buzzword

As Naga Munchetty’s experience at the BBC shows, challenging inflammatory language can be hazardous writes Priyamvada Gopal in The Guardian

Racism is emphatically not a matter of subjective “experience”. It has objective structural force that can be identified not just in discriminatory practices but in differing entitlements and unequal access to resources, representation and opportunities. “Go back to where you came from” is not just a wounding phrase that almost all people of colour and migrants have heard. Its material consequences include actual expulsions such as those of the “Windrush children” and, of course, discriminatory travel, migration and citizenship policies.

Another way of deflecting engagement with race is to personalise matters. As the sociologist Robin DiAngelo notes, insisting that there was no “intent” to be racist or asking, “how can you say I’m racist, you don’t know me”, are manifestations of “white fragility”. In this scheme, only exceptionally “bad” people can be racist, and therefore the mere suggestion of racism is often treated as more serious and hurtful than racism itself. DiAngelo makes the important point that discussions about race are bound to be uncomfortable for members of dominant communities who have to come to terms with their own entanglement in an unfair system.

To avoid such discomfort and difficulty is to refuse change. I know this from personal experience as an upper-caste woman from India who has also benefited from a deeply iniquitous system. I too have felt defensive, but there’s no way to change things without admitting to the existence of caste or race supremacy, and dealing with the fact of inevitable complicity and the inherited privilege that disadvantages others.

At the same time, “whataboutery” leads nowhere. Whenever I speak of race and empire in the British media, I receive emails asking: “What about caste” and inviting me to “go back” to India to address the caste system instead. People not normally known for a deep interest in class matters will also suddenly ask “what about the working classes?”. A now retired female manager once told me that, although sexism was still an issue at Cambridge University, racism was not. There’s no need to pit race, class, caste, gender, ability or sexuality against each other: there are no free passes in an inequitable world where each brutality shapes the others.

There are also no “race cards”. People who raise issues of racial exclusion or abuse are not demanding special treatment; on the contrary, they are arguing against the special privileges bestowed on the majority or dominant group. Most of us who raise issues of racism do so with hesitation, feeling vulnerable as we do so and fearing inevitable social and institutional reprisals. Meet a race whistleblower and you meet a deemed “troublemaker”, a position with unpleasant institutional consequences.

Discussion of race is often derailed by bogeys such as “reverse racism”. Of course it’s possible for people of colour to display hostile or denigrating attitudes towards other races, Asian anti-blackness being one example. “Racism towards white people” is not, however, systemic and does not have policy consequences. Certificates from “best friends” of colour declaring a person to be “not racist” are also void. Just as having a mother does not make men free of sexism in a patriarchal world, having a black best friend, spouse or even child cannot absolve individuals from complicity in racist language and actions. Indeed, ethnic minority politicians may themselves be used to justify such things as blackface or xenophobia.

No one is claiming that victims of racism are pure or noble. People are never purely victims and everyone has to ask tough questions of themselves. It is perfectly possible, for example, to be at once homophobic yourself and a victim of racism. Both must be tackled.

Far from “wallowing in victimhood”, people who challenge racism are acting as responsible agents of change. At a time when the forces of violent racism are globally in the ascendant once again, we can help them along by refusing to name it as such.

Alternatively, we can do the right thing: actively acknowledge racism’s existence and try to rein in its power. If we don’t choose to have difficult and urgent discussions openly, then “diversity” will remain a meaningless buzzword where people’s bodies are included in institutions but their voices are silenced.

Brexit opponents clash. ‘Inflammatory language is increasingly the norm, yet the word racism remains muffled under a curious omerta.’ Photograph: Teri Pengilley/Guardian

Politicians accuse each other of being cowardly collaborators who surrender, betray and capitulate. Commentators on television warn of riots. Inflammatory language is increasingly the norm in public life, yet one word remains muffled under a curious omertà. The BBC presenter Naga Munchetty was only the latest to discover that describing something as racist, even in a measured way, can get you into a lot of trouble.

For many people of colour in largely white institutions, this is a familiar prohibition that works to shut down much-needed discussion and create a repressive and demoralising silence.

Racism is that strange phenomenon, apparent everywhere and apparently nowhere. People believe that not “seeing” race, or being “colourblind”, is progressive, when it is merely evasive. What might happen if we took it as given that after six centuries of European imperial rule it would be astounding if most of us – including people of colour – were not shaped by the racial hierarchies put in place? The term white supremacy may invoke images of hooded Klansmen burning crosses, but it actually refers to an entrenched system of racial domination that once justified colonisation and slavery, the legacies of which still shape economic, political and social orders, particularly in the west.

Politicians accuse each other of being cowardly collaborators who surrender, betray and capitulate. Commentators on television warn of riots. Inflammatory language is increasingly the norm in public life, yet one word remains muffled under a curious omertà. The BBC presenter Naga Munchetty was only the latest to discover that describing something as racist, even in a measured way, can get you into a lot of trouble.

For many people of colour in largely white institutions, this is a familiar prohibition that works to shut down much-needed discussion and create a repressive and demoralising silence.

Racism is that strange phenomenon, apparent everywhere and apparently nowhere. People believe that not “seeing” race, or being “colourblind”, is progressive, when it is merely evasive. What might happen if we took it as given that after six centuries of European imperial rule it would be astounding if most of us – including people of colour – were not shaped by the racial hierarchies put in place? The term white supremacy may invoke images of hooded Klansmen burning crosses, but it actually refers to an entrenched system of racial domination that once justified colonisation and slavery, the legacies of which still shape economic, political and social orders, particularly in the west.

Racism is emphatically not a matter of subjective “experience”. It has objective structural force that can be identified not just in discriminatory practices but in differing entitlements and unequal access to resources, representation and opportunities. “Go back to where you came from” is not just a wounding phrase that almost all people of colour and migrants have heard. Its material consequences include actual expulsions such as those of the “Windrush children” and, of course, discriminatory travel, migration and citizenship policies.

Another way of deflecting engagement with race is to personalise matters. As the sociologist Robin DiAngelo notes, insisting that there was no “intent” to be racist or asking, “how can you say I’m racist, you don’t know me”, are manifestations of “white fragility”. In this scheme, only exceptionally “bad” people can be racist, and therefore the mere suggestion of racism is often treated as more serious and hurtful than racism itself. DiAngelo makes the important point that discussions about race are bound to be uncomfortable for members of dominant communities who have to come to terms with their own entanglement in an unfair system.

To avoid such discomfort and difficulty is to refuse change. I know this from personal experience as an upper-caste woman from India who has also benefited from a deeply iniquitous system. I too have felt defensive, but there’s no way to change things without admitting to the existence of caste or race supremacy, and dealing with the fact of inevitable complicity and the inherited privilege that disadvantages others.

At the same time, “whataboutery” leads nowhere. Whenever I speak of race and empire in the British media, I receive emails asking: “What about caste” and inviting me to “go back” to India to address the caste system instead. People not normally known for a deep interest in class matters will also suddenly ask “what about the working classes?”. A now retired female manager once told me that, although sexism was still an issue at Cambridge University, racism was not. There’s no need to pit race, class, caste, gender, ability or sexuality against each other: there are no free passes in an inequitable world where each brutality shapes the others.

There are also no “race cards”. People who raise issues of racial exclusion or abuse are not demanding special treatment; on the contrary, they are arguing against the special privileges bestowed on the majority or dominant group. Most of us who raise issues of racism do so with hesitation, feeling vulnerable as we do so and fearing inevitable social and institutional reprisals. Meet a race whistleblower and you meet a deemed “troublemaker”, a position with unpleasant institutional consequences.

Discussion of race is often derailed by bogeys such as “reverse racism”. Of course it’s possible for people of colour to display hostile or denigrating attitudes towards other races, Asian anti-blackness being one example. “Racism towards white people” is not, however, systemic and does not have policy consequences. Certificates from “best friends” of colour declaring a person to be “not racist” are also void. Just as having a mother does not make men free of sexism in a patriarchal world, having a black best friend, spouse or even child cannot absolve individuals from complicity in racist language and actions. Indeed, ethnic minority politicians may themselves be used to justify such things as blackface or xenophobia.

No one is claiming that victims of racism are pure or noble. People are never purely victims and everyone has to ask tough questions of themselves. It is perfectly possible, for example, to be at once homophobic yourself and a victim of racism. Both must be tackled.

Far from “wallowing in victimhood”, people who challenge racism are acting as responsible agents of change. At a time when the forces of violent racism are globally in the ascendant once again, we can help them along by refusing to name it as such.

Alternatively, we can do the right thing: actively acknowledge racism’s existence and try to rein in its power. If we don’t choose to have difficult and urgent discussions openly, then “diversity” will remain a meaningless buzzword where people’s bodies are included in institutions but their voices are silenced.

Thursday, 4 April 2019

Fifty shades of white: the long fight against racism in romance novels

For decades, the world of romantic fiction has been divided by a heated debate about racism and diversity. Is there any hope of a happy ending? By Lois Beckett in The Guardian

Last year, the Strand Bookstore in New York convened an all-star panel titled Let’s Woman-Splain Romance! The line to get in the door stretched down the block, and the room was thrumming with glee even before the panel started. This was not an audience that needed to be told that smart women read romance novels, or that the genre could be feminist. The authors speaking that night were all big names, including Beverly Jenkins, an iconic author of African American historical romance – who blew a kiss to the audience as she was introduced to whoops of delight – and two breakout stars of the previous year, Alisha Rai and Alyssa Cole.

The subtext of the event was clear: it was not just a celebration of romance novels, but a celebration of diversity within an industry that has long been marked by pervasive racism. For decades, publishers had confined many black romance authors to all-black lines, marketed only to black readers. Some booksellers continued to shelve black romances separately from white romances, on special African American shelves. Accepted industry wisdom told black authors that putting black couples on their covers could hurt sales, and that they should replace them with images of jewellery, or lawn chairs, or flowers. Other authors of colour had struggled to get representation within the genre at all.

Jenkins and Cole, who are black, and Rai, who is south Asian, had been fighting against these barriers for years. Their success – as authors of critically acclaimed love stories sold in Walmarts and drug stores across the country – had not made them any less vocal.

The panel moderator turned the “diversity” question to Rai first. Her latest series was, he began, “very multicultural and [with] a broad spectrum of sexual identity in it. There’s a lot going on in the sweeping saga that has hot romance at the centre of it.” He paused.

“I’m sorry, is that a question?” Rai asked, very calmly. In her day job, she was a lawyer.

The moderator started referring to a previous time when romances had been less diverse, but Rai cut him off.

“We’re still not at mission accomplished,” she said. And the issue was not really diversity. “It’s about reality.”

Romance novelist Alisha Rai

“Can I say nipples in here?” Rai continued. The audience giggled. “Many, many years ago, when I first started writing, someone said to me: ‘Oh, this is the first book where the heroine had brown nipples, like on the page,’ and I was like: ‘What? That’s crazy!’ She was a long-time romance reader. I thought about it. I’m pretty sure nipples come in all shades, but they’re always, like, pink on the page, or berries, or some kind of pink fruit.”

By this point, the audience was guffawing and Jenkins was bent over with laughter. “What happens is, it goes into one book, it goes into 10 books, people read those books and write their own books, and suddenly, everybody’s got pink nipples,” Rai said. “And they forget about the fact that that’s not reality.”

Jenkins straightened up. “I always had brown nipples in my books,” she said. “That’s one of the things readers said early on: ‘No offence – we’re tired of reading about pink nipples.’”

The conversation shifted to other implausible but time-honoured turns of phrase: looking daggers, panther-like grace. Everyone laughed, and there were cupcakes, and at that moment in the bookshop, in front of this multiracial panel of bestselling writers, it might have been easy to think that the future of diverse romance had already arrived. Except, the authors kept warning, it had not.

Romance readers compound the sin of liking happy, sexy stories with the sin of not caring much about the opinions of serious people, which is to say, men. They are openly scornful of the outsiders who occasionally parachute in to report on them. In late 2017, Robert Gottlieb – the former editor of the New Yorker and unsurpassable embodiment of the concept “august literary man” – wrote a jocular roundup of that season’s best romances in the New York Times Book Review. He opined that romance was a “healthy genre” and that its effect was “harmless, I would imagine. Why shouldn’t women dream?” The furious public response from romance readers – “patriarchal ass” was among the more charitable comments – prompted a defensive editor’s note from the NYT, which later announced it was hiring a dedicated romance columnist, who happened to be both a woman and a long-time fan of the genre.

Coverage of the romance industry often dwells on the contrast between the nubile young heroines of the novels and the women who actually write the books: ordinary women with ordinary bodies, dressed for their own comfort. Reporting on the first annual conference of the Romance Writers of America (RWA) – the major trade association for romance authors – in 1981, the Los Angeles Times wrote that the 500 authors who attended were “not the stuff of which romance heroines are made – at mostly 40 and 50, they were less coquette and more mother-of-the-bride”. That observation – combining creeping horror at the idea that middle-aged women might be interested in sex, with indifference to the fact that male authors are rarely judged for failing to resemble James Bond – is typical.

Part of the intense scorn romance authors face is the result of their rare victory. They have built an industry that caters almost completely to women, in which writers can succeed on the basis of their skill, not their age or perceived attractiveness. Romance writing is one of few careers where it is possible for a woman to break into the industry, self-taught, at 40 or 50, alongside or after raising her children, and achieve the highest levels of professional success. Not only possible; typical. Nor is romance is some marginal part of the book industry – in 2016, it represented 23% of the overall US fiction market, and has been estimated to be worth more than $1bn a year in the US alone. There is something threatening about all this, says Pamela Regis, the director of Nora Roberts Center for American Romance at McDaniel College – hence all the “sneering and leering”.

Romance novels follow a strict formula: they must be love stories, and by the end the protagonist must achieve their “happily-ever-after”, often referred to as the “HEA”. (Less traditional authors now sometimes end with the HFN, or “happy for now”.) The genre’s guarantee to readers is that its heroines’ labour of love will never go unpaid. As the RWA puts it: “In a romance, the lovers who risk and struggle for each other and their relationship are rewarded with emotional justice.” Justice, in this context, means “unconditional love”.

Outsiders often associate romance novels with historical “bodice-rippers”, but the genre is a vast continent with many ecosystems. There are chaste Christian romances set among the Amish, where the hero and heroine’s closest contact is the exchange of steaming hot baked goods; erotic romances featuring sex clubs and orgies; novels set in the medieval Scottish highlands or among cowboys in the American west; series romances that tell the individual love stories of each player on fictional football or hockey teams.

For all this diversity of genre, the romance industry itself has remained overwhelming white, as have the industry’s most prestigious awards ceremony, the Ritas, which are presented each year by the RWA. Just like the Oscars in film, a Rita award is the highest honour a romance author can receive, and winning can mean not only higher sales, but also lasting recognition from peers. And just like the Oscars, the Ritas have become the centre of controversy over unacknowledged racism and bias in the judging process.

An Extraordinary Union by Alyssa Cole

Last year, however, many observers felt that this was sure to change. One of the standout novels of 2017 had been Alyssa Cole’s An Extraordinary Union, an interracial romance set during the civil war. The book had already won a number of awards and made multiple best-of-the-year lists.

When the Rita awards finalists were announced in March 2018, An Extraordinary Union was nowhere to be seen. A novel rated exceptional by critics had been not even been deemed as noteworthy by an anonymous judging panel of Cole’s fellow romance writers. The books that had beat Cole as finalists in the best short historical romance category were all by white women, all but one set in 19th-century Britain, featuring white women who fall in love with aristocrats. The heroes were, respectively, one “rogue”, two dukes, two lords and an earl.

What followed, on Twitter, was an outpouring of grief and frustration from black authors and other authors of colour, describing the racism they had faced again and again in the romance industry. They talked about white editors assuming black writers were aspiring authors, even after they had published dozens of books; about white authors getting up from a table at the annual conference when a black author came to sit down; about constant questions from editors and agents about whether black or Asian or Spanish-speaking characters could really be “relatable” enough.

Then, of course, there were the readers. “People say: ‘Well, I can’t relate,’” Jenkins told NPR a few years ago, after watching white readers simply walk past her table at a book signing. “You can relate to shapeshifters, you can relate to vampires, you can relate to werewolves, but you can’t relate to a story written by and about black Americans?”

In response to the outcry over the Ritas, the RWA went back over the past 18 years of Rita award finalists and winners. During that time, the RWA acknowledged in a statement posted on its website, books by black authors had accounted for less than 0.5% of the total number of Rita finalists. “It is impossible to deny that this is a serious issue and that it needs to be addressed,” the statement from the RWA board noted. According to the current president of the Romance Writers of America, a black woman has never actually won a Rita.

The romance novel industry found itself facing a similar crisis over racism and representation as Hollywood, or the news industry, or the Democratic party. But one thing that sets it apart is that it is facing this challenge as an industry dominated by women – specifically, white women. Would anti-racist activism, and the backlash against it, play out differently in an industry run by women – and, in particular, by women who were writers and readers, who by definition loved stories of joy and reconciliation?

The backbone of the US romance community is the nearly 100 local chapters of the RWA, which provide mentorship and peer support for women embarking on the long and lonely work of novel-writing. On a Saturday afternoon last spring, I attended a meeting of the Heart of Carolina Romance Writers. A few dozen white women gathered in a classroom at a small for-profit college outside of Raleigh, North Carolina, and the meeting began, as it always does, with the good news.

“I did a presentation at the Wake County library with other historical fiction authors, and we dressed up like our time period: we had Victorian and Edwardian and World War II,” one author announced, to murmurs of approval. Another author, who had just released a new book, said: “It’s the best launch I’ve ever had, and it was an independent, so I thank y’all because I’m sure you guys are the ones who bought it.” The women followed each update, big or small, with a round of applause.

The most exciting update had been saved for last. One of the chapter’s most senior members was Hannah Meredith, a 74-year-old with dyed auburn hair, a brisk demeanour and the deep, throaty voice of a woman who had been a smoker for nearly six decades. “I have good news. I have a new cover – ” Meredith began, before pausing dramatically – “for a book that is nominated for a Rita!”

There was applause and cheers. Meredith’s novel, Song of the Nightpiper, a fantasy romance, had been named as one of eight finalists in the paranormal romance category. Nancy Lee Badger, the chapter president at the time, seemed as excited as Meredith. A Rita finalist in their chapter! At age 74! With Meredith’s triumph duly celebrated, the group moved on to the main focus of the session, a breezy presentation on writing more “dynamic dialogue”, from author Allie Pleiter, who had sold more than 1.4m books.

At the end of the meeting, with a few minutes left, I asked the members what they made of the Rita controversy. Many of them, it turned out, had been following the debate closely, and their reactions were divided. “I was really surprised,” said Meredith. “You look around and you go: ‘This isn’t a very diverse group.’” But, she added, “it has been, and people have moved away and taken other jobs, that were of colour. But I don’t think any of them ever felt like they weren’t appreciated.”

A younger woman in a gingham shirt pushed back at this. “That’s the point. As white women we can’t see it. We’re coming from a privileged place where we’re not even aware of it.”

A woman in a polo shirt noted that when All About Romance, an independent romance review site, had released its list of best books of the year, there had been no black authors on it. The site had subsequently tried to correct this, but in their correction, they confused the names of two of the most famous black romance authors, Brenda Jackson and Beverly Jenkins. “Basically, my impression as an old white woman, is that we need to listen more to people,” she said.

Some of the white authors were less convinced that the lack of black Rita finalists and winners was proof of any racism in the judging process. It was hard for anyone to win a Rita, they argued. They themselves had entered, they had not won and they were not complaining.

Badger did not say much during the meeting, but she had talked to me earlier on the phone. She acknowledged that only about three of her 50 local members were black and that those numbers were “poor”, given the diversity of North Carolina. But, she noted, there were already plenty of rules to encourage an inclusive environment. “How do I make sure that women of colour, Asian, etc, are able to reap the benefits of being part of this organisation?” she said. “I can’t force them to come to a meeting.”

A few minutes into the conversation, Badger spontaneously began talking about recent efforts to remove Raleigh’s monuments to Confederate soldiers. Badger was not a southerner – she grew up in New York – but she had been disturbed by efforts to get rid of the statutes. I asked what connection she saw between the debate over the Rita awards and the effort to take down confederate monuments, which had sparked conflict in cities across the US.

In both situations, Badger said, only a small group of people were objecting, but in response everyone would be forced to change. “It’s one group of people that is not happy with the monuments because they’re saying they’re monuments to slavery, but I don’t think so,” said Badger. “It’s just too bad, that it upsets somebody at 200 – however many, 150 years later.” In the romance world, the small group getting the attention were “women of colour” and nobody seemed to be talking about Asians, or senior citizens, or “including all these other people, that aren’t making a fuss”.

Kianna Alexander

While her own feelings were conflicted, Badger did believe the controversy was important enough to set aside time for her chapter to talk it over with a journalist, and some of the members felt that the anger over the lack of diversity within romance was fully justified. “I think there’s a problem,” the woman in the polo shirt had concluded. “And I think that women of colour need to be in the lead. But of course, in our group, we’re all white.”

This was a point that many of the women kept returning to – the fact that everyone in the room that day was white. There was no consensus on what this fact demonstrated – one of the group’s past presidents was black, several people pointed out – but it was a fact that demanded explanation, that left even the women most adamant that there was no problem a little unsettled.

A long-time chapter member mentioned that one of these former black members, a writer named Kianna Alexander, had been part of the chapter for three or four years. There was a clear reason why Alexander was no longer coming to their meetings, the woman said, and it was purely logistical. “She has a very complicated family situation, so it’s difficult for her to make the drive here.”

It was about an hour-and-a-half drive south from where the romance writers group met to the small North Carolina town where Alexander lived with her family. I drove the route in the darkness that night. Alexander had promised to meet me in the morning for breakfast.

Romance novels – the realm of women’s fantasies – have always been political. When the Berlin Wall fell, the British romance publisher Mills & Boon, which is owned by Harlequin, made a point of handing out more than 700,000 copies of their romance novels to East German women. “Sex! Capitalism! Individual choice!” the books seemed to announce. Within three years, Mills & Boon was selling millions of books across the former eastern bloc.

Because romance novels follow a strict formula, the genre is often seen as “peculiarly hollow”, says Jayashree Kamblé, the vice-president of the International Association for the Study of Popular Romance, and an English professor at New York’s LaGuardia Community College. In fact, she argues, the rigid conventions of the genre, with its familiar plot arcs and predetermined happy ending, make it a revealing space for tracking women’s desires and fears at different moments in history.

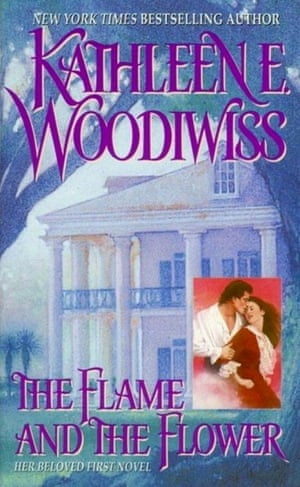

Through the 1960s, many romance novels had stayed relatively prim, with the sex mostly implied. Authors experimenting with more sensual stories still had to negotiate with editors determined to uphold what they saw as moral standards. But the widespread adoption of the pill, and changing attitudes to women’s sexuality, would finally open up new literary possibilities. Scholars date the emergence of the sexual revolution in romance fiction to 1972, with the publication of Kathleen Woodiwiss’s The Flame and The Flower, a bodice-ripping historical romance featuring explicit sex scenes.

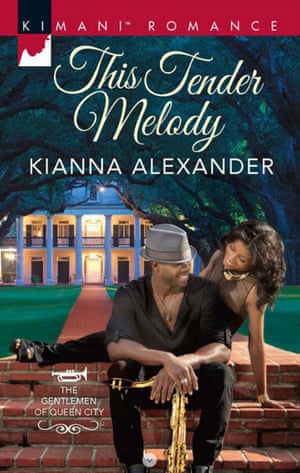

This Tender Melody by Kianna Alexander

It wasn’t just booksellers that were segregating Alexander’s love stories. The process started with the publisher. Harlequin, which merged decades ago with the British romance publisher Mills & Boon, was acquired in 2014 by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp and is now a division of HarperCollins, has sold more than 6.7bn books, and currently publishes 110 titles a month, with romance series designed to suit every taste. Novels are grouped by genre or “heat” levels, from sweet and chaste to steamy and explicit. But the Harlequin line that Alexander wrote for, Kimani, was grouped by only one thing: race. The heroes in Kimani books can be any race or ethnicity, Alexander said, but Kimani heroines, like their authors, are black.

Alexander and many of her fellow black authors have long had mixed feelings about Kimani. The series had a dedicated readership, and Alexander’s Kimani books sold better than anything else she has published. Some black authors told me they believed that for some readers a dedicated black romance series really was a quick way to locate what they wanted to read.

But, like being shelved in the black section, black authors also believed that being part of a segregated line limited their sales, cutting them off from readers of other races who might also enjoy their work. Some former Harlequin authors even alleged that Kimani had been given separate and unequal treatment by the publisher: less marketing, fewer chances for authors to promote their books.

In May 2017, Harlequin had announced that it would be gradually phasing out five lines, including Kimani, for financial reasons. If the publisher had quickly integrated black authors into its other Harlequin lines, this decision could have garnered broad support. Instead, nearly a year later, in the spring of 2018, Alexander and other Kimani authors were still in limbo, unsure if they had a future with the brand, or if the closure of Harlequin’s segregated black line would simply mean fewer opportunities for black authors overall.

A spokeswoman for the publishing giant HarperCollins, Harlequin’s parent company, declined to respond to specific questions about Harlequin’s past and present editorial choices regarding romances by black authors and featuring black characters. “We value the discussion about diversity that is taking place in publishing and are working to increase representation and inclusion in our stories, as well as in our author base,” she wrote.

Harlequin’s dedicated black romance line is relatively new, having launched in 2006 after being acquired from another publisher. For almost 100 years before that, the company had rarely published romances with black heroes and heroines at all.

That changed in the early 1980s, when Harlequin recruited Vivian Stephens, a charismatic black editor and one of the founders of the RWA, who championed what was then referred to as “ethnic” romance. In 1984, when Harlequin published its first black romance by a black American author, many readers got their books through a subscription sent directly to their homes. Before publication, Stephens told the book’s author, Sandra Kitt, that Harlequin executives in Canada “were really concerned that their subscribers would be up in arms about, quote unquote ‘this black book’,” Kitt recalled. When the novel, Adam and Eva, did eventually come out, the company received only four letters of complaint. It ended up selling respectably and became one of Harlequin’s frequently reissued classics.

But after working at Harlequin for about two years, Stephens was fired. She told me she was never given any explanation for why she was forced out. After Stephens left, Harlequin continued to publish novels by Sandra Kitt – but only the ones she wrote about white characters. It would take another decade, until the blockbuster success of Terry McMillan’s 1992 novel Waiting to Exhale, which detailed the romantic travails of four professional black women, for the US publishing industry to begin to realise what a lucrative market black women readers might be. Beverly Jenkins told me that in 1996, when she published her breakthrough novel, Indigo, which featured a dark-skinned black woman as the heroine, she was often approached by readers who were moved to tears at seeing themselves represented in a romance novel. Seeing their reactions, she cried, too.

Marketing black love stories to black women was one thing, but publishers remained sceptical about the idea that white readers would read those same stories. In the late 1990s, Suzanne Brockmann, a white author writing a sequence of Harlequin romances about sexy Navy Seals, decided that she wanted to make a black character the hero of her next book. It was, she admits now, something of a “white saviour” move. Brockmann’s thinking, she told me, was that Harlequin simply didn’t realise the commercial opportunity it was missing by not printing more black romances.

Sandra Kitt

Harlequin published Brockmann’s book in 1998, but she was shocked by the way the company dealt with its publication. She recalled her publisher saying: “You will make half the money because we will print half the copies. We cannot send it to our subscription list.” It was the same argument Harlequin had made 14 years earlier: “We’ll get angry letters.” It wasn’t just black characters that Harlequin rejected, according to Brockmann. She said she was also told they would not publish a novel with an Asian American as the central character. (Brockmann later moved on to another publisher.)

The experience of authors who wrote early Harlequin novels with black characters suggests that white readers might be more willing to embrace black stories than white publishers and editors have traditionally assumed. At the same time, it seems likely that white readers’ racism has played a role in the industry’s persistent exclusion of black stories. Several black authors described meeting white women at book signings who would ask to get a book signed, but emphasise that they were buying the books for a black friend, or a black colleague, certainly not for themselves. Others had seen or heard comments from white readers that they found happy stories about black women unrealistic.

A particularly infuriating comment, some black authors said, is when white women describe taking a chance on a romance with a black heroine, and then express surprise at how easily they were able to identify with the story. Shirley Hailstock, a black novelist and past president of RWA, told me about a fan letter she once received from a white romance author. She sent me a photograph of the letter, with the signature concealed.

“Dear Shirley,” the white author had written, in a neat cursive hand, “I’m writing to let you know how much I enjoyed Whispers of Love. It’s my first African American romance. I guess I might sound bigoted, but I never knew that black folks fall in love like white folks. I thought it was just all sex or jungle fever I think “they” call it. Silly of me. Love is love no matter what colour or religion or nationality, as sex is sex. I guess the media has a lot to do with it.”

The letter, dated 3 June 1999, was signed, “Sincerely, a fan”.

In 2015, the year Donald Trump launched his campaign for the White House, the RWA began a serious effort to address racism and diversity within its membership. For years, black authors had talked about feeling unwelcome in the organisation, and having to find refuge in what they called the “Second RWA”, where they advised each other as they negotiated the microaggressions and outright bigotry of the larger organisation.

Now the RWA, spurred on by board member Courtney Milan – a former law professor, bestselling author and prominent advocate of diversity within romance – began to take a more proactive approach, from ensuring more authors of colour joined the board, to publicly calling out a publisher for excluding black authors.

The efforts have sparked a backlash from some of the RWA’s 10,000 members, more than 80% of whom are white. (By contrast, about 61% of the US population as a whole is non-Hispanic white.) HelenKay Dimon, the group’s current president, who is white, told me she regularly receives letters from white members expressing concern that “now nobody wants books by white Christian women” or criticising the romance association’s sudden “political correctness”. Dimon acknowledged the difficulties that all romance writers were facing – traditional publishers buying fewer books, an increasingly crowded ebook market – but, she continued, there is “a group of people who are white and who are privileged, who have always had 90% of everything available, and now all of a sudden, they have 80%. Instead of saying: ‘Ooh, look, I have 80%,’ they say: ‘Oh, I lost 10! Who do I blame for losing 10?’”

One of the public flashpoints over the board’s diversity efforts came in the summer of 2017, when Linda Howard, a bestselling white author who had been among RWA’s first members, wrote in a private RWA author forum that the board’s focus on “social issues” was driving some members away. “Diversity for the sake of diversity is discrimination,” Howard wrote, arguing that the group’s resources should not be focused “on one (or more) group to the exclusion of others”.

Howard, who left RWA over the furious response to her comments, told me that she was not eager to rehash the incident. “I wasn’t against diversity. I was against the way the board was handling it,” Howard said, when we spoke recently. “I thought it could have been handled better and gotten better results.” She said she understood that the “big pool of anger” around the diversity debate came from a lifetime of people being treated as if they weren’t as good as everyone else.

I asked her what had stuck with her, more than a year later, out of the many angry responses that she received. “Social media has a lot to answer for,” she said. “Social media makes it possible for people to attack en masse, and not deal with the human aspect.”

While Howard felt that if people had been speaking face-to-face, the conversation would have been more constructive, others disagree. Many activists argue that Twitter has been a powerful tool for amplifying conversations – and demands for accountability – that might otherwise have been stifled or ignored. But in response to this new dynamic, a counter-narrative has emerged where people calling for change are criticised for being uncivil or even dangerous. Alisha Rai and Alyssa Cole – who, along with Milan, are among the most prominent voices in the Twitter debate – told me they had been labelled “mean girls” or “diversity bullies” for talking about racism in a way that was not “nice”.

“‘Niceness’ is going on Twitter and Facebook and saying how you were bullied by the people talking about diversity,” Cole said. “We would always be described as screaming, harassing. All of these weird terms … ”

“Censorship,” Rai added. “Policing.”

Rai continued: “They tell us niceness means you sit down and you shut up and you take what you’re given. And you don’t complain, because if you’re given anything, you should be grateful, right?”

It has become commonplace for pundits to lament that social media has undermined civilised debate and to suggest that angry Twitter mobs may be harmful to democracy. But when I spoke to Dee Davis, who ended her term as RWA president last year, she saw a utility in the kind of combative approach some romance authors of colour had taken on Twitter. To make real change, she said, “You need the fighters. You need the gladiators.”

If you were on Twitter, you should know what you had signed up for, she told me. “You don’t go into a hockey arena if you’re not ready to play hockey.” And, she added, if the board’s commitment to diversity meant that the RWA lost members, that would just be the way it was. “Any change is always going to make somebody go: ‘Well, this isn’t for me any longer,” and I think that’s OK,” Davis said.

Davis agreed that the conversation we were having about RWA seemed similar to the debates going on within the Democratic party, about what to do about “diversity”, about whether the more radical or moderate wing of the party would hold sway, who might be alienated by the choices the leadership was making. The root of the conflict in RWA, as in the Democratic party, Davis believed, was that her own generation, the baby boomers, were hanging on to power too long. They were used to get their own way, used to being influential, and it was time for them to let go and they would not.

For Cole and Rai, it wasn’t just the pushback to calls for diversity that worried them. They were also concerned that publishers might treat diverse romances as a passing trend, and that white authors might be best positioned to profit from writing “diverse” stories. In 2016, on a conference call presided over by Harlequin executives, “diversity” was listed among the themes that the publisher wanted to see more often, according to one author who was on the call. On the list were “more marriages of convenience, more sheiks, more baby themes, more alpha heroes, more diversity”. To the author on the call, it sounded as if Harlequin was treating diversity “more like a marketing opportunity.”

The annual awards gala of the Romance Writers of America is a very pleasant event. There is no dinner, only dessert and wine, and there are virtually no men present. The ceremony is the culmination of a frenetic five-day industry networking conference, which has a strikingly different atmosphere from most publishing industry events. Instead of the usual tote bag or briefcase, the savviest attendees carry a foldable rolling plastic crate from Walmart, which they fill with dozens of free novels. The 2018 conference took place at a Sheraton hotel in Denver, Colorado, in July, and the schedule included educational seminars such as History Undressed, an expert’s guide to underwear through the centuries, and a session on firefighting led by one bestselling author’s firefighter husband, which involved him hoisting up participants and carrying them around the room.

The dress code for the Rita award ceremony itself, appropriately for an industry focused on women’s happiness, is: whatever makes you feel festive. Some authors get their hair done and wear floor-length sequinned dresses, chandelier earrings, corsages. Others choose loose pants and tunic tops and sensible shoes. At the 2018 ceremony, an award-winning author paired a red satin dress with sequinned Converse sneakers, and another wore a high-low ballgown with hiking sandals, proving that it is possible, now and then, to have it all.

The golden Rita statuette is awarded in 13 categories, from best erotic romance to best paranormal romance. On the night, as the winners, often choking up, read their acceptance speeches off their phones, they talked about the women who had helped them get here. They talked about the constant likelihood of failure, about writing love stories as a second or third job, about learning how to close the door to their children and partners in order to write. “Thank you for the great sex,” Kristan Higgins, the bestselling author married to the firefighter, blurted out to him as she accepted the award for best mainstream fiction novel with a central romance. “My children are not watching tonight,” she added, after a moment.

Kianna Alexander, the young black author from North Carolina, was seated in the center of the ballroom, at the same table as Hannah Meredith, the 74-year-old Rita finalist from the Heart of Carolina Romance Writers, the local chapter Alexander had left after 2016. The conference, like the local chapter, was overwhelmingly white, but there were a scattering of authors of colour in the room for the award ceremony. Alexander clapped politely, her face very still, as one white woman after another stood up, cried, and accepted her award.

The culmination of the ceremony was the lifetime achievement award, which was being presented to Suzanne Brockmann, the white author who had written a black Harlequin romance in the late 90s. As she took to the stage to give her keynote speech, the mood shifted. Brockmann’s son, who is gay, presented the award to his mother, and she started by talking about him. Brockmann told the audience that at the 2008 conference, she had wanted to give a speech celebrating California’s decision to legalise gay marriage. “I was told that the issue was divisive and some RWA members would be offended,” Brockmann said. “I regret not walking out. I should’ve rocked the living fuck out of that boat. Instead, I was nice. Instead I went along.”

Alyssa Cole

This was just the warmup. Now, she turned to her main point. “RWA, I’ve been watching you grapple as you attempt to deal with the homophobic, racist white supremacy on which our nation and the publishing industry is based. It’s long past time for that to change. But hear me, writers, when I say: it doesn’t happen if we’re too fucking nice.”

Brockmann had considered the possibility that she would have to keep talking through icy silence. Instead, many of the thousands of women in the room were already rising to give her a standing ovation. At Alexander’s table, she and Meredith both stayed seated. Meredith was sitting, arms folded, leaning in to tell her sister, who was sitting next to her, that she did not approve of the speech. Alexander was intensely aware of how visible she would be if she stood at that moment, with white women sitting all around her. She thought Brockmann’s speech was headed in the right direction, but she wasn’t sure.

“Here comes the part of my speech where I get ‘political,’” Brockmann continued. “When you write what you see and what you know and what you have been told to believe, like books set in a town where absolutely no people of colour or gay people live … ? You are perpetuating exclusion, and the cravenness and fear that’s at its ancient foundation. Yeah, I’m talking to you, white, able, straight, cis, allegedly Christian women. And don’t @ me with ‘Not all white women’. Because 53% of us plunged us into our current living hell,” she said, referring to exit polls that the majority of white women voted for Trump in the 2016 election.

By the end of her speech, the vast majority of the white women in the room were giving Brockmann a standing ovation. And Alexander had stood, too, and lifted one fist into the air.

At the dance party after the award ceremony, on a small wooden dance floor set atop the vast, brightly lit expanse of hotel lobby carpet, dozens of women danced barefoot to Talk Dirty to Me, or swayed gently, wine glasses in hand. Piles of glittering heels lay abandoned at the side of the dance floor. Alexander, who had done a Facebook livestream from the party for her fans, was examining the Twitter reaction to Brockmann’s speech. Some authors of colour were sharing approving reaction gifs. Others said later it had made them emotional to hear the exclusion they had faced addressed so publicly.

But not everyone was enthusiastic. According to Damon Suede, a well-known RWA board member, angry emails poured into his inbox during the speech, including from some people he had previously regarded as friends, complaining that the awards should not have permitted a speech “bashing” conservatives.

Hannah Meredith had not stood up to applaud Brockmann’s speech. But she had not walked out either. After the ceremony, as she smoked outside the hotel, she explained why the speech made her uncomfortable. She had not voted for Donald Trump, she said, so she didn’t take the remarks about his supporters personally. But, she said: “I will be honest, when it became very political, when it became sending [people] to go out and vote, I’m not sure it belonged.”

“I’m inundated with politics,” Meredith continued. “I want a space where I’m not. That doesn’t mean you can’t talk about being inclusive. Love is love, and I agree with that.” Meredith said she wanted RWA to address diversity without being overtly political. “Maybe it’s old age, but I feel like everyone is trying to push everyone apart. My gang is the good gang. If we’re all divisive, divisive, divisive, we’re screwed.”

What Meredith said about wanting a space without politics echoed what Kianna Alexander had told me about why she had left the Heart of Carolina Romance Writers group: the sense that some people saw politics as distant or optional, rather than something that directly shaped their lives. For Alexander, Trump’s mockery of a disabled reporter during the campaign, his open racism, were personal threats to her, her husband and her son. There was no space where she could avoid politics.

Eight months after the denunciation of white supremacy at the romance industry’s annual conference, the RWA announced the latest Rita award finalists. The group’s president had been optimistic that more black authors and authors of colour would finally be represented. The board had announced it would track scores given by individual judges and be on the lookout for any hint of bias. Anecdotally, at least, it seemed that more authors of colour had decided to enter their books, hopeful that the judging would be more fair.

Instead, what the results of the peer-judged contest seemed to reveal was a quiet, continued resistance. The 2019 finalist list featured almost 80 authors in total – and only three of them were authors of colour. This time, Alyssa Cole had submitted a book that had been named one of the New York Times’ 100 notable books of the year, a rare honour for any romance novel. As with her critically acclaimed entry the year before, it had not been rated highly enough to final in the Ritas.

“I don’t know how they could take the message any other way than: ‘We don’t feel like we’re wanted here,’” Dimon, RWA’s current president, said of the group’s members of colour. The responses from some white authors – including the prominent author who tweeted: “I agree 100% that this must change, but can’t we wait five minutes for the finalists to enjoy their day?” – only made writers of colour more frustrated and angry. One tweeted that the debate inside RWA’s private message board had grown so acrimonious that a white author had sent her an email threatening to sue her. More than one writer suggested that the Rita awards, in their current form, were illegitimate.

Alexander had watched the Rita results come in, and it had ruined her morning. But, she told me, there was no question that she was going to stay a member and keep fighting. She had begun to see signs of real progress, even if they were still too rare. The long work of pitching and revising was paying off: in recent months, she had heard one black author after another announce book deals. In February, Alexander had signed a contract with Harlequin’s Desire line, which features dramatic romances set against a backdrop of luxury and glamour. Alexander said she knew of at least five other black authors who had transitioned from Kimani, the black line that was being phased out, to a different Harlequin line. And, for the first time, Alexander saw an ad for a black Harlequin author in one of the women’s magazines sold at grocery store checkout lines. The magazine wasn’t Essence or Ebony: it was a black Harlequin author being marketed to everyone.

Last year, the Strand Bookstore in New York convened an all-star panel titled Let’s Woman-Splain Romance! The line to get in the door stretched down the block, and the room was thrumming with glee even before the panel started. This was not an audience that needed to be told that smart women read romance novels, or that the genre could be feminist. The authors speaking that night were all big names, including Beverly Jenkins, an iconic author of African American historical romance – who blew a kiss to the audience as she was introduced to whoops of delight – and two breakout stars of the previous year, Alisha Rai and Alyssa Cole.

The subtext of the event was clear: it was not just a celebration of romance novels, but a celebration of diversity within an industry that has long been marked by pervasive racism. For decades, publishers had confined many black romance authors to all-black lines, marketed only to black readers. Some booksellers continued to shelve black romances separately from white romances, on special African American shelves. Accepted industry wisdom told black authors that putting black couples on their covers could hurt sales, and that they should replace them with images of jewellery, or lawn chairs, or flowers. Other authors of colour had struggled to get representation within the genre at all.

Jenkins and Cole, who are black, and Rai, who is south Asian, had been fighting against these barriers for years. Their success – as authors of critically acclaimed love stories sold in Walmarts and drug stores across the country – had not made them any less vocal.

The panel moderator turned the “diversity” question to Rai first. Her latest series was, he began, “very multicultural and [with] a broad spectrum of sexual identity in it. There’s a lot going on in the sweeping saga that has hot romance at the centre of it.” He paused.

“I’m sorry, is that a question?” Rai asked, very calmly. In her day job, she was a lawyer.

The moderator started referring to a previous time when romances had been less diverse, but Rai cut him off.

“We’re still not at mission accomplished,” she said. And the issue was not really diversity. “It’s about reality.”

Romance novelist Alisha Rai

“Can I say nipples in here?” Rai continued. The audience giggled. “Many, many years ago, when I first started writing, someone said to me: ‘Oh, this is the first book where the heroine had brown nipples, like on the page,’ and I was like: ‘What? That’s crazy!’ She was a long-time romance reader. I thought about it. I’m pretty sure nipples come in all shades, but they’re always, like, pink on the page, or berries, or some kind of pink fruit.”

By this point, the audience was guffawing and Jenkins was bent over with laughter. “What happens is, it goes into one book, it goes into 10 books, people read those books and write their own books, and suddenly, everybody’s got pink nipples,” Rai said. “And they forget about the fact that that’s not reality.”

Jenkins straightened up. “I always had brown nipples in my books,” she said. “That’s one of the things readers said early on: ‘No offence – we’re tired of reading about pink nipples.’”

The conversation shifted to other implausible but time-honoured turns of phrase: looking daggers, panther-like grace. Everyone laughed, and there were cupcakes, and at that moment in the bookshop, in front of this multiracial panel of bestselling writers, it might have been easy to think that the future of diverse romance had already arrived. Except, the authors kept warning, it had not.

Romance readers compound the sin of liking happy, sexy stories with the sin of not caring much about the opinions of serious people, which is to say, men. They are openly scornful of the outsiders who occasionally parachute in to report on them. In late 2017, Robert Gottlieb – the former editor of the New Yorker and unsurpassable embodiment of the concept “august literary man” – wrote a jocular roundup of that season’s best romances in the New York Times Book Review. He opined that romance was a “healthy genre” and that its effect was “harmless, I would imagine. Why shouldn’t women dream?” The furious public response from romance readers – “patriarchal ass” was among the more charitable comments – prompted a defensive editor’s note from the NYT, which later announced it was hiring a dedicated romance columnist, who happened to be both a woman and a long-time fan of the genre.

Coverage of the romance industry often dwells on the contrast between the nubile young heroines of the novels and the women who actually write the books: ordinary women with ordinary bodies, dressed for their own comfort. Reporting on the first annual conference of the Romance Writers of America (RWA) – the major trade association for romance authors – in 1981, the Los Angeles Times wrote that the 500 authors who attended were “not the stuff of which romance heroines are made – at mostly 40 and 50, they were less coquette and more mother-of-the-bride”. That observation – combining creeping horror at the idea that middle-aged women might be interested in sex, with indifference to the fact that male authors are rarely judged for failing to resemble James Bond – is typical.

Part of the intense scorn romance authors face is the result of their rare victory. They have built an industry that caters almost completely to women, in which writers can succeed on the basis of their skill, not their age or perceived attractiveness. Romance writing is one of few careers where it is possible for a woman to break into the industry, self-taught, at 40 or 50, alongside or after raising her children, and achieve the highest levels of professional success. Not only possible; typical. Nor is romance is some marginal part of the book industry – in 2016, it represented 23% of the overall US fiction market, and has been estimated to be worth more than $1bn a year in the US alone. There is something threatening about all this, says Pamela Regis, the director of Nora Roberts Center for American Romance at McDaniel College – hence all the “sneering and leering”.

Romance novels follow a strict formula: they must be love stories, and by the end the protagonist must achieve their “happily-ever-after”, often referred to as the “HEA”. (Less traditional authors now sometimes end with the HFN, or “happy for now”.) The genre’s guarantee to readers is that its heroines’ labour of love will never go unpaid. As the RWA puts it: “In a romance, the lovers who risk and struggle for each other and their relationship are rewarded with emotional justice.” Justice, in this context, means “unconditional love”.

Outsiders often associate romance novels with historical “bodice-rippers”, but the genre is a vast continent with many ecosystems. There are chaste Christian romances set among the Amish, where the hero and heroine’s closest contact is the exchange of steaming hot baked goods; erotic romances featuring sex clubs and orgies; novels set in the medieval Scottish highlands or among cowboys in the American west; series romances that tell the individual love stories of each player on fictional football or hockey teams.

For all this diversity of genre, the romance industry itself has remained overwhelming white, as have the industry’s most prestigious awards ceremony, the Ritas, which are presented each year by the RWA. Just like the Oscars in film, a Rita award is the highest honour a romance author can receive, and winning can mean not only higher sales, but also lasting recognition from peers. And just like the Oscars, the Ritas have become the centre of controversy over unacknowledged racism and bias in the judging process.

An Extraordinary Union by Alyssa Cole

Last year, however, many observers felt that this was sure to change. One of the standout novels of 2017 had been Alyssa Cole’s An Extraordinary Union, an interracial romance set during the civil war. The book had already won a number of awards and made multiple best-of-the-year lists.

When the Rita awards finalists were announced in March 2018, An Extraordinary Union was nowhere to be seen. A novel rated exceptional by critics had been not even been deemed as noteworthy by an anonymous judging panel of Cole’s fellow romance writers. The books that had beat Cole as finalists in the best short historical romance category were all by white women, all but one set in 19th-century Britain, featuring white women who fall in love with aristocrats. The heroes were, respectively, one “rogue”, two dukes, two lords and an earl.

What followed, on Twitter, was an outpouring of grief and frustration from black authors and other authors of colour, describing the racism they had faced again and again in the romance industry. They talked about white editors assuming black writers were aspiring authors, even after they had published dozens of books; about white authors getting up from a table at the annual conference when a black author came to sit down; about constant questions from editors and agents about whether black or Asian or Spanish-speaking characters could really be “relatable” enough.

Then, of course, there were the readers. “People say: ‘Well, I can’t relate,’” Jenkins told NPR a few years ago, after watching white readers simply walk past her table at a book signing. “You can relate to shapeshifters, you can relate to vampires, you can relate to werewolves, but you can’t relate to a story written by and about black Americans?”

In response to the outcry over the Ritas, the RWA went back over the past 18 years of Rita award finalists and winners. During that time, the RWA acknowledged in a statement posted on its website, books by black authors had accounted for less than 0.5% of the total number of Rita finalists. “It is impossible to deny that this is a serious issue and that it needs to be addressed,” the statement from the RWA board noted. According to the current president of the Romance Writers of America, a black woman has never actually won a Rita.

The romance novel industry found itself facing a similar crisis over racism and representation as Hollywood, or the news industry, or the Democratic party. But one thing that sets it apart is that it is facing this challenge as an industry dominated by women – specifically, white women. Would anti-racist activism, and the backlash against it, play out differently in an industry run by women – and, in particular, by women who were writers and readers, who by definition loved stories of joy and reconciliation?

The backbone of the US romance community is the nearly 100 local chapters of the RWA, which provide mentorship and peer support for women embarking on the long and lonely work of novel-writing. On a Saturday afternoon last spring, I attended a meeting of the Heart of Carolina Romance Writers. A few dozen white women gathered in a classroom at a small for-profit college outside of Raleigh, North Carolina, and the meeting began, as it always does, with the good news.

“I did a presentation at the Wake County library with other historical fiction authors, and we dressed up like our time period: we had Victorian and Edwardian and World War II,” one author announced, to murmurs of approval. Another author, who had just released a new book, said: “It’s the best launch I’ve ever had, and it was an independent, so I thank y’all because I’m sure you guys are the ones who bought it.” The women followed each update, big or small, with a round of applause.

The most exciting update had been saved for last. One of the chapter’s most senior members was Hannah Meredith, a 74-year-old with dyed auburn hair, a brisk demeanour and the deep, throaty voice of a woman who had been a smoker for nearly six decades. “I have good news. I have a new cover – ” Meredith began, before pausing dramatically – “for a book that is nominated for a Rita!”

There was applause and cheers. Meredith’s novel, Song of the Nightpiper, a fantasy romance, had been named as one of eight finalists in the paranormal romance category. Nancy Lee Badger, the chapter president at the time, seemed as excited as Meredith. A Rita finalist in their chapter! At age 74! With Meredith’s triumph duly celebrated, the group moved on to the main focus of the session, a breezy presentation on writing more “dynamic dialogue”, from author Allie Pleiter, who had sold more than 1.4m books.

At the end of the meeting, with a few minutes left, I asked the members what they made of the Rita controversy. Many of them, it turned out, had been following the debate closely, and their reactions were divided. “I was really surprised,” said Meredith. “You look around and you go: ‘This isn’t a very diverse group.’” But, she added, “it has been, and people have moved away and taken other jobs, that were of colour. But I don’t think any of them ever felt like they weren’t appreciated.”

A younger woman in a gingham shirt pushed back at this. “That’s the point. As white women we can’t see it. We’re coming from a privileged place where we’re not even aware of it.”

A woman in a polo shirt noted that when All About Romance, an independent romance review site, had released its list of best books of the year, there had been no black authors on it. The site had subsequently tried to correct this, but in their correction, they confused the names of two of the most famous black romance authors, Brenda Jackson and Beverly Jenkins. “Basically, my impression as an old white woman, is that we need to listen more to people,” she said.

Some of the white authors were less convinced that the lack of black Rita finalists and winners was proof of any racism in the judging process. It was hard for anyone to win a Rita, they argued. They themselves had entered, they had not won and they were not complaining.

Badger did not say much during the meeting, but she had talked to me earlier on the phone. She acknowledged that only about three of her 50 local members were black and that those numbers were “poor”, given the diversity of North Carolina. But, she noted, there were already plenty of rules to encourage an inclusive environment. “How do I make sure that women of colour, Asian, etc, are able to reap the benefits of being part of this organisation?” she said. “I can’t force them to come to a meeting.”

A few minutes into the conversation, Badger spontaneously began talking about recent efforts to remove Raleigh’s monuments to Confederate soldiers. Badger was not a southerner – she grew up in New York – but she had been disturbed by efforts to get rid of the statutes. I asked what connection she saw between the debate over the Rita awards and the effort to take down confederate monuments, which had sparked conflict in cities across the US.

In both situations, Badger said, only a small group of people were objecting, but in response everyone would be forced to change. “It’s one group of people that is not happy with the monuments because they’re saying they’re monuments to slavery, but I don’t think so,” said Badger. “It’s just too bad, that it upsets somebody at 200 – however many, 150 years later.” In the romance world, the small group getting the attention were “women of colour” and nobody seemed to be talking about Asians, or senior citizens, or “including all these other people, that aren’t making a fuss”.

Kianna Alexander

While her own feelings were conflicted, Badger did believe the controversy was important enough to set aside time for her chapter to talk it over with a journalist, and some of the members felt that the anger over the lack of diversity within romance was fully justified. “I think there’s a problem,” the woman in the polo shirt had concluded. “And I think that women of colour need to be in the lead. But of course, in our group, we’re all white.”

This was a point that many of the women kept returning to – the fact that everyone in the room that day was white. There was no consensus on what this fact demonstrated – one of the group’s past presidents was black, several people pointed out – but it was a fact that demanded explanation, that left even the women most adamant that there was no problem a little unsettled.

A long-time chapter member mentioned that one of these former black members, a writer named Kianna Alexander, had been part of the chapter for three or four years. There was a clear reason why Alexander was no longer coming to their meetings, the woman said, and it was purely logistical. “She has a very complicated family situation, so it’s difficult for her to make the drive here.”

It was about an hour-and-a-half drive south from where the romance writers group met to the small North Carolina town where Alexander lived with her family. I drove the route in the darkness that night. Alexander had promised to meet me in the morning for breakfast.

Romance novels – the realm of women’s fantasies – have always been political. When the Berlin Wall fell, the British romance publisher Mills & Boon, which is owned by Harlequin, made a point of handing out more than 700,000 copies of their romance novels to East German women. “Sex! Capitalism! Individual choice!” the books seemed to announce. Within three years, Mills & Boon was selling millions of books across the former eastern bloc.

Because romance novels follow a strict formula, the genre is often seen as “peculiarly hollow”, says Jayashree Kamblé, the vice-president of the International Association for the Study of Popular Romance, and an English professor at New York’s LaGuardia Community College. In fact, she argues, the rigid conventions of the genre, with its familiar plot arcs and predetermined happy ending, make it a revealing space for tracking women’s desires and fears at different moments in history.