“Blessed is the nation that doesn’t need heroes" Goethe. “Hero-worship is strongest where there is least regard for human freedom.” Herbert Spencer

Search This Blog

Monday 11 July 2022

Friday 15 April 2022

Follow The Hollow: Politics Of Consumption Among The Middle-Classes In India And Pakistan

Nadeem F Paracha in The Friday Times

Consumerism, or the preoccupation of society with the acquisition of consumer goods, largely emerged from the 19th century onwards. It began to really take off from the early 20th century, when the idea of mass production of consumer goods fully materialised. Consumer goods are often those that are not exactly a necessity. They are acquired for ‘superficial’ purposes. It is, therefore, not a coincidence that the birth of modern-day advertising and/or marketing ploys, too, began to evolve more rapidly during this period. Their aim was to describe consumer goods as a necessity without which one could not become an identifiable member of society.

In 2018, I went through decades of ‘consumer demographic’ data of some of the world’s leading marketing and advertising firms (between the 1950s and early 2000s). These included advertising firms in Pakistan and India as well. The data shows that most makers of consumer goods and services have continued to ‘target’ the middle-classes, or the ‘aspirational classes.’ These have remained prominent buyers of consumer goods. They are also the most prominent classes in the social and economic spaces of major cities.

However, this is not the case when it comes to politics. The middle-classes may be a part of the electorate, but in most regions, their presence is minimal in the actual corridors of power. The middle-classes have often expressed frustration after feeling that their path towards holding the levers of political power is being blocked by members of the political elite who were born into their status instead of climbing their way up as the middle-classes want to.

Modern mainstream politics is the result of certain revolutionary 17th-, 18th- and 19th-century upheavals in Europe which saw the emergence and expansion of the middle-classes. They gradually pushed out the old political elites (the monarchs, the Church, landed gentries, etc.), and replaced these with themselves at the top. The politics that evolved during this process was a product of modernity as defined by the so-called ‘Age of Enlightenment.’

Inch by inch, religion was demystified and relegated to the private sphere; newly formed polities began to be defined as nations that were linked to integrated economies; and the ‘pre-modern’ past was denounced as a realm ravaged by wars, plagues, brutal rulers, widespread poverty, religious persecution and exploitation, superstition, and short lifespans.

The political system which the expanding middle-classes adopted and evolved was democracy. Initially, they trod the ‘Aristotelian’ path which posited that a large, prosperous middle class may mediate between rich and poor, creating the structural foundation upon which democratic political processes may operate (J. Glassman, The Middle Class and Democracy in Socio-Historical Perspective, 1995).

Middle-class prosperity and growth were dependent on modern economic activity which functioned outside the old agrarian structures, and took place in the expanding urban spaces. These spaces attracted labour from rural areas who transformed in to becoming the working-class (the proletariat). During the upward-mobility of the middle-classes, they engineered a democracy that was to constitutionally protect their properties and newfound power and wealth. But as the size of the working-classes grew, it became necessary to create room for them in the political system, if social and political upheavals were to be avoided.

Traditionally, working-class interests in democracies leaned left or towards socialist or welfare policies. As a reaction, the middle-classes moved to the right (F. Wunderlich in The Antioch Review, Spring 1945). The middle-classes therefore, became more invested in curbing, or at least lessening, the electoral influence of the working-classes by voting for conservative parties which treated social-democratic ideas as Trojan horses through which communism would invade and usurp all political and economic power of the ‘hard-working middle-classes.’ However, from within the post-19th-century political elites (in industrialised countries) also emerged parties that evolved into becoming the parties of the working-classes. The growing number of blue-collared voters in the cities necessitated this.

This created a fissure within the middle-classes. A large section of them was now willing to undermine democracy, or a system that it had crafted itself. This section began to view it as a threat to its economic interests. Here is where we see the growth of authoritarian and fascist ideas permeating middle-class political discourses in Europe, and the emergence of demagogues such as Hitler, Mussolini, Franco, etc. The aforementioned section’s radical move to the (anti-democracy) right can be understood as an emotional decision born from the fear of being swallowed by the classes below (the ‘masses’).

When the American president F.D. Roosevelt stated that “the only thing we need to fear was fear itself,” he was trying to address just that. He understood that fear was capable of pushing reasonable folk into authoritarian/totalitarian/populist camps.

After the defeat of German and Italian fascisms, social-democratic policies thrived in the democratic West.

They succeeded in largely pacifying middle-class fears. The middle-classes now stood on the left and the right, yet within the mainstream democratic system which continued to safeguard and police their economic interests, and, at the same time, facilitate the interests of the working-classes as well.

But from the mid-1970s, as the nature of capitalism began to change, and the industrialised countries entered the ‘post-industrial stage,’ things flipped. Between the two World Wars, sections of Western middle-classes had largely moved to the right and far-right, whereas the working-classes had moved to the left. But when the service sector began to produce more wealth than the industrial sector, positions switched.

The service sector has always been dominated by the middle-classes. A gradual decrease in industrial activity and/or with this activity shifting to developing countries (due to cheap labour, etc.), the working-classes were left stranded and feeling bitter. They began to break away from mainstream democratic paradigms and embrace a populism which preyed on the fears of this class as it struggled to cope with the drastic economic shift that was eroding blue-collar economic interests.

So, whereas, during the first half of the 20th century, a large number from the middle-class milieu, fearing that they were about to be overwhelmed by the working-classes, had exited the mainstream democratic paradigm, and had embraced authoritarian ideas and regimes, in the second half of the 21st century, it was the working-classes who did the same by supporting the rise of right-wing nationalism and populism.

The South Asian flip: politics of consumption

In developing countries such as India and Pakistan, right-wing nationalism and populism are still very much the domain of the middle-classes. This is understandable because the process of industrialisation was slow and late in these regions, and so was the expansion of the middle-classes. The economies of both the countries during their first few decades were overwhelmingly agrarian. Industrialisation did not begin in earnest till over a decade after their formation.

This meant a large rural population and a steadily growing urban proletariat. Therefore, democracy in this case, though controlled by an elite, was (for electoral purposes) driven to address the interests of the peasants, small farmers and the working-classes. It was social-democratic in nature. This did not sit well with the middle-classes. They were squeezed between a ruling elite and the classes below. They constantly feared being relegated or overwhelmed by the ‘masses’ because the ruling elite in control of political parties were talking to the masses more than they did to the middle-classes. The elite were, of course, courting sections that had larger number of votes.

Till the early 2000s, middle-class economic and political interests in Pakistan were mostly stimulated by military dictators (S. Akbar Zaidi, Issues in Pakistan’s Economy: A Political Economy Perspective, 2nd Edition, 2005). This is why the middle-classes in Pakistan are more receptive to non-democratic forces and currents, even though they were only provided a semblance of political power by the dictatorships. But the size of this class is growing and so is its economic influence. It feels blocked by the electoral political elites from complimenting its economic influence with political power.

But the fact is, as the middle-classes in Europe had done between the two World Wars, the middle-classes in India and Pakistan too, consciously or unconsciously, are destroying the very idea and system that was originally crafted to serve their interests the most. This brings us to consumerism.

Between the two World Wars when large sections of the urban middle-classes in various European countries began to fear that the classes below (the ‘masses’) would use democracy to undermine middle-class interests, the middle-classes became antagonistic towards democracy — an ideology and system of government that they had themselves created. They then went on to facilitate the rise of anti-democracy forces that barged in and overthrew the political elites who were engaging with the masses through electoral politics.

The middle-classes in South Asia have been in a dilemma of being squeezed between two forces (the electoral elite and the working-classes/peasants). So, these middle-classes have failed to fully carve out a place and identity for themselves as a political entity within a political system that is largely informed by the engagement between the aforementioned forces. According to the historian Markus Daechsel, this saw the South Asian middle-classes indulge in what Daechsel calls “politics of self-expression” (Daechsel, The Politics of Self-Expression: The Urdu Middleclass Milieu in Mid-Twentieth Century India and Pakistan, 2009).

This form of politics is a rebellion against the dynamics of mainstream politics, which the middle-class milieu dismisses as being ‘corrupt.’ This corruption is not only denounced in material terms, but is also censured for contaminating or enslaving a community’s or individual’s inner self that needs to be liberated. Instruments such as the constitution, and institutions such the parliament, are seen as restraints that were stopping people from seeking liberation. Liberation from what? This is never convincingly explained.

The aim of the politics of self-expression is not exactly a way to find a place in mainstream societal politics. Instead, it is a flight into an alternative ideological universe where all societal constraints that plague the middle-class self would cease to exist (Daechsel, ibid). In fact, Daechsel explains the politics of self-expression as a product of the consumer society. According to Colin Campbell, a new ethics of romanticism driven by emotional introspection, a hunger for stimulation and arousal and a penchant for daydreaming, helped to give birth to a consumer society that alone could sustain the onward march of capitalism (C. Campbell, The Romantic Ethic and the Spirit of Modern Consumerism, 1987).

To Daechsel, this drove people to develop an obsession with identities. The middle-classes remain to be at the core of consumerism. A consumer society has been defined as one in which there is no societal reality other than the relationship between consumers and branded commodity. People are entirely what they consume; no immediate relationships of political power, economic exchange or cultural capital matter anymore (J. Baudrillard, The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures, 1970).

According Daechsel, the middle-class milieu (in South Asia) was, by virtue of its material culture, persuaded to use consumption as an outlet for its frustrated socio-political ambitions. The fact that consumer identities have something ‘hollow’ about them, that they substitute a fetishistic relationship with consumer goods for ‘real’ societal relations, was precisely what made them so attractive. A constituency that could not otherwise exist as a class, due to the constraints imposed by a mainstream political economy that they became suspicious of, found in consumption a space where it could establish some form of a unified cultural consciousness.

Daechsel then adds that the trouble with consumer identities is that consumer goods are believed to reflect a person’s innermost being, but at the same time rely on the garish and the mundane to produce identities. Consumption is not about great deeds in world history, but about the choice of toothpaste and cigarettes. Yet, consumer goods through the manner in which they are marketed, provide the stuff to form identities. Marlboro smokers were rugged individualists, Coca Cola drinkers value the happiness of being part of a wholesome family, iPhone users are savvy folk who are ‘creative’ and ‘fun-loving,’ etc.

The politics of self-expression is an attempt to make consumer identities secure and ‘serious’ by dressing up consumption activity as politics. The language of politics thus becomes a caricature of advertising language; it retains all the hyperbole. For example, the word ‘liberation’ in such nature of politics is as ‘serious’ as it is when used in ads of male or female undergarments! But in politics of expression, it replaces advertising’s playfulness and self-irony with the certainty of assumed prophetic airs (Daechsel, ibid).

In consumer societies the language of politics becomes a caricature of advertising language. For example, a young man or woman is more likely to come across the word Revolution in an advertisement than in politics. Advertisements and political rhetoric both exchange words which may end up meaning nothing.

The middle-classes in India and Pakistan have gone to war with conventional politics, which they still fear is pitched against them. But even in India, where these classes have succeeded to somewhat break into and disturb the once impenetrable fortress of the country’s ‘rational’ political elites, they have no convincing alternatives. Or the alternatives are creating unprecedented social and political turmoil because they are emerging from the politics of self-expression.

According to Daechsel, the methodology in this context is a direct reflection of the logic of a consumer society. Both in Pakistan and India, ‘rational’ political instruments and democratic norms are being attacked by the middle-classes through the creation of spectacles that are being beamed by the new media universe. They are like marketing stunts.

Events such as openly undermining the constitution, beating up and humiliating foes, burning passports and flags, etc., have turned the perpetrators into political brands that are immediately and often quite literally ‘consumed’. Daechsel views all this as a suicide mission (of the South Asian middle-classes). It is an ultimate extension of the self-expressionist longing for intoxication, a self-indulgent form of ‘political’ activity that is supposedly based on a supreme ideology, but in reality gives the person involved a taste of the ultimate power trip. Just like an expensive brand of car or watch would.

Established political instruments and democratic norms are being attacked by the middle-classes through the creation of spectacles that are being beamed by the new media universe.

Daechsel writes, “If there is a final conclusion to be drawn from this exposition of the politics of self-expressionism in India and Pakistan, it has to be the following: the development of a middle-class through an expansion of the social role of consumption offers no guarantee for a better political culture. Persistent contradictions between a consumer society and other forms of societal organisations will stimulate forms of self-expressionist radicalism that may be very hard to control. Far from being the historical carrier of the voice of reason and modernity, the consumer middle-class could well turn out as the destroyer of the world that gave birth to it.”

This is quite apparent in the ways many middle-class men and women in South Asia have willingly drowned the notion that their acts in this context could be undermining their own political and, especially, economic interests. They seem to have readily gone blind to this fact in their bid to devour politics like they would a consumer brand, but one which is marketed as a product to give them instant bursts of liberation, empowerment and greatness.

Thursday 17 March 2022

Thursday 18 November 2021

Sunday 31 October 2021

On Stupidity: How do Smart People Outsmart Themselves

What is stupidity? Ever since the mid-20th century, the idea of stupidity, especially in the context of politics, has been studied by various sociologists and psychologists. One of the pioneers in this regard was the German scholar and theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

During the rise of Nazi rule in Germany, Bonhoeffer was baffled by the silence of millions of Germans when the Nazis began to publicly humiliate and brutalise Jewish people. Bonhoeffer condemned this. He asked how could a nation that had produced so many philosophers, scientists and artists, suddenly become so apathetic and even sympathetic towards state violence and oppression.

Unsurprisingly, in 1943, Bonhoeffer was arrested. Two years later, he was executed. While awaiting execution, Bonhoeffer began to put his thoughts on paper. These were posthumously published in the shape of a book, Letters and Papers from Prison. One of the chapters in the book is called, ‘On Stupidity.’ Bonhoeffer wrote: “Every strong upsurge of power in the public sphere, be it political or religious, infects a large part of humankind with stupidity. The power of the one needs the stupidity of the other.”

According to Bonhoeffer, because of the overwhelming impact of a rising power, humans are deprived of their inner independence and they give up establishing an autonomous position towards the emerging circumstances. They become mere tools in the hands of the power, and begin to willingly surrender their capacity for independent thinking. Bonhoeffer wrote that holding a rational debate with such a person is futile, because it feels that one is not dealing with a person, but with slogans and catchwords.

So, to Bonhoeffer, stupidity was not about lack of intelligence, but about a mind that had almost voluntarily closed itself to reason, especially after being impacted and/or swayed by the rise of an assertive external power.

In a 2020 essay for The New Statesman, the British philosopher Sacha Golob writes that being stupid and dumb were not the same thing. For example, intelligence (or lack thereof) can somewhat be measured through IQ tests. But even those who score high in these tests can do ‘stupid’ things or carry certain ‘stupid ideas.’

Golob gave the example of the novelist Arthur Conan Doyle, who created the famous fictional character, Sherlock Holmes. Holmes, a private detective, was an ideal product of the ‘Age of Reason’, imagined by Doyle as a man who shunned emotions and dealt only in reason, logic and the scientific method. Yet, later on in life, Doyle became the antithesis of his character, Holmes. He got into a silly argument with the celebrated illusionist Harry Houdini when the latter rubbished Doyle’s belief that one could communicate with spirits (in a seance).

The question is, how could a man who had created a super-rationalist character such as Sherlock Holmes, begin to believe in seances? In fact, Doyle also began to believe in the existence of fairies. Every time someone would successfully debunk Doyle’s beliefs, Doyle would go to great lengths to provide a counter-argument, but one which was even more absurd.

Golob writes this is what stupidity is. And it can even be found in supposedly very intelligent people too. According to the American psychologist Ray Hyman, “Conan Doyle used his smartness to outsmart himself.” This can also answer why one sometimes comes across highly educated and informed men and women unabashedly spouting conspiracy theories that have either been convincingly debunked, or cannot be proven outside the domain of wishful thinking. By continuing to insist on the validity of such theories, one is simply using his/her smartness to outsmart oneself.

What about the leaders whose rise to power, according to Bonhoeffer, triggers stupidity across a large body of people? Take the example of today’s prominent populists, whose supporters are often referred to as being stupid. But as mentioned earlier, these leaders too are explained in a similar manner.

The truth is, dumbness, if it means a substantial lack of intelligence, is not what explains prominent political leaders. Had they been dumb, they would never be at the top of the heap. But as we have already established, stupidity and dumbness are two very different things; leaders can be stupid.

In this context, Golob explains stupidity as “the lack of conceptual resources.” By this he means that some leaders lack the right conceptual tools for the job. He writes that this can lead to a ‘conceptual failure’, where a leader is unable to fully grasp the concept of (political, economic or social) reality that he/she is operating in. They may excel in what they understand, but enter the domain of stupidity when they don’t. However, it is quite clear by now that today’s populist leaders may have had the intelligence to propel themselves to power, but they really do not have the conceptual tools to remain there.

Take PM Imran Khan. As an opposition leader, he understood well the concept of fiery, emotional rhetoric that can become a venting vessel for many. However, this tool becomes impotent in the conceptual context of actually being in power. Khan lacks the conceptual tools to understand the many economic and political quagmires the country has slid into. The more he fails in this, the more he falls back on concepts that he actually understands: i.e. fiery rhetoric (but one that does not sound very convincing anymore), and issues of morality.

He understands the latter well because, when he was a dashing ‘playboy’ in his pre-political days, he was often attacked for being immoral. He understood what the concept of morality is in Pakistani society. He now uses this as a tool to distract his thinning support from his obvious lack of understanding of what is actually happening around him in terms of the country’s drastic economic meltdown.

So, politically and economically, as things crumble around him, he stubbornly continues to “address issues of social immorality” because, by now, this is the only concept he can grasp. This is another case of political stupidity and conceptual failure, or of smartness outsmarting itself.

Friday 20 August 2021

Monday 16 August 2021

Friday 13 August 2021

Saturday 5 June 2021

Sunday 16 May 2021

Islamophobia And Secularism

Prime Minister Imran Khan frequently uses the term ‘Islamophobia’ while commenting on the relationship between European governments and their Muslim citizens. Khan has often been accused of lamenting the treatment meted out to Muslims in Europe, but remaining conspicuously silent about cases of religious discrimination in his own country.

Then there is also the case of Khan not uttering a single word about the Chinese government’s apparently atrocious treatment of the Muslim population of China’s Xinjiang province.

Certain laws in European countries are sweepingly described as being ‘Islamophobic’ by Khan. When European governments retaliate by accusing Pakistan of constitutionally encouraging acts of bigotry against non-Muslim groups, the PM bemoans that Europeans do not understand the complexities of Pakistan’s ‘Islamic’ laws.

Yet, despite the PM repeatedly claiming to know the West like no other Pakistani does, he seems to have no clue about the complexities of European secularism.

Take France for instance. French secularism, called ‘Laïcité’ is somewhat different than the secularism of various other European countries and the US. According to the contemporary scholar of Western secularism, Charles Taylor, French secularism is required to play a more aggressive role.

In his book, A Secular Age, Taylor demonstrates that even though the source of Western secularism was common — i.e. the emergence of ‘modernity’ and its political, economic and social manifestations — secularism evolved in Europe and the US in varying degrees and of different types.

Secularism in the US remains largely impersonal towards religion. But in France and in some other European countries, it encourages the state/government to proactively discourage even certain cultural dimensions of faith in the public sphere which, it believes, have the potential of mutating into becoming political expressions.

Nevertheless, to almost all prominent philosophers of Western democracy across the 19th and 20th centuries, the idea of providing freedom to practise religion is inherent in secularism, as long as this freedom is not used for any political purposes.

According to the American sociologist Jacques Berlinerblau in A Call to Arms for Religious Freedom, six types of secularism have evolved. The American researcher Barry Kosmin divides secularism into two categories: ‘soft’ and ‘hard’. Most of Berlinerblau’s types fall in the ‘soft’ category. The hard one is ‘State Sponsored Atheism’ which looks to completely eliminate religion. This type was practised in various former communist countries and is presently exercised in China and North Korea. One can thus place Laïcité between Kosmin’s soft and hard secular types.

The existence of what is called ‘Islamophobia’ in secular Europe and the US has increasingly drawn criticism from various quarters. According to the French author Jean-Loïc Le Quellec, the term is derived from the French word ‘islamophobie’ that was first used in 1910 to describe prejudice against Muslims.

L.P. Sheridan writes in the March 2006 issue of the Journal of Interpersonal Violence that the term did not become widely used till 1991. According to Roland Imhoff and Julia Recker in the Journal of Political Psychology, a wariness had already been building in the West towards Muslims because of the aggressively anti-West ‘Islamic’ Revolution in Iran in 1979, and the violent backlash in some Muslim countries against the publication of the novel Satanic Verses by the British author Salman Rushdie in 1988.

Islamophobia is one of the many expressions of racism towards ‘the other’. Racisms of varying nature have for long been present in Europe and the US. Therefore Imhoff and Recker see Islamophibia as “new wine in an old bottle.” It is a relatively new term, but one that has also been criticised.

Discrimination against race, faith, ethnicity, caste, etc., is present in almost all countries. But its existence gets magnified when it is present in countries that describe themselves as liberal democracies.

Whereas Islamophobia is often understood as a phobia against Islam, there are also those who find this definition problematic. To the term’s most vehement critics, not only has it overshadowed other aspects of racism, of which there are many, it is also mostly used by ‘radical Muslims’ to curb open debate.

In a study, the University of Northampton’s Paul Jackson writes that the term should be replaced with ‘Muslimphobia’ because the racism in this context is aimed at a people and not towards the faith, as such. However, he does add that the faith too should be open for academic debate.

In an essay for the 2016 anthology The Search for Europe, Bichara Khader writes that racism against non-white migrants in Europe intensified in the 1970s because of a severe economic crisis. Khader writes that this racism was not pitched against one’s faith.

According to Khader, whereas this meant that South Asian, Arab, African and Caribbean migrants were treated as an unwanted whole based on the colour of their skin, from the 1980s onwards, the Muslims among these migrants began to prominently assert their distinctiveness. As the presence of veiled women and mosques grew, this is when the ‘migration problem’ began to be seen as a ‘Muslim problem’.

The Muslim diaspora in the West began to increasingly consolidate itself as a separate whole. Mainly through dress, Muslim migrants began to shed the identity of their original countries, creating a sort of universality of Muslimness.

But this also separated them from the non-Muslim migrant communities, who were facing racial discrimination as well. Interestingly, this imagined universality of Muslimness was also exported back to the mother countries of Muslim migrants.

Take the example of how, in Pakistan, some recent textbooks have visually depicted the dress choices of Pakistani women. They are almost exactly how some second and third generation Muslim women in the West imagine a woman should dress like.

But there was criticism within Pakistan of this depiction. The critics maintain that the present government was trying to engineer a cultural type of how women ought to dress in a country where — unlike in some other Muslim countries — veiling is neither mandatory nor banned. This has only further highlighted the fact that identity politics in this context in Pakistan is being influenced by the identity politics being flexed by certain Muslim groups in the West.

Either way, because of the fact that it is a recent phenomenon, identity politics of this nature is not organic as such, and will continue to cause problems for Muslims within and away.

Saturday 6 February 2021

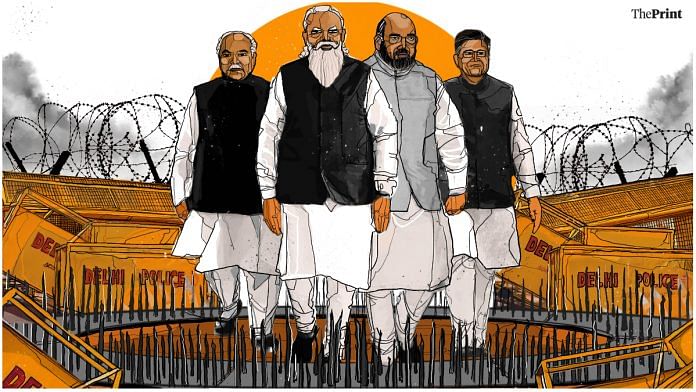

Modi govt has lost farm laws battle, now raising Sikh separatist bogey will be a grave error

Protests over the three farm reform laws are well into the third month now. There are six key facts, or facts as we see them, that we can list here:

1. The farm laws, by and large, are good for the farmers and India. At various points of time, most major political parties and leaders have wanted these changes. However, many of you might still disagree. But then, this is an opinion piece. I explained it in detail in this, Episode 571 of #CutTheClutter.

2. Whether the laws are good or bad for the farmer no longer matters. In a democracy, all that matters is what people affected by a policy change believe — in this case, the farmers of the northern states. Facts don’t matter if you’ve failed to convince them.

3. The Modi government is right when it says this is no longer about the farm laws. Because nobody is talking about MSP, subsidies, mandis and so on. Then what’s it about?

4. The short answer is, it is about politics. And why not? There is no democracy without politics. When the UPA was in power, the BJP opposed all its good ideas, from the India-US nuclear deal to FDI in insurance and pension. Now it’s implementing the same policies at the rate of, say, 6X.

5. As far as the farm laws are concerned, the Modi government has already lost the battle. Again, you can disagree. But this is my opinion. And I will make my case.

6. Finally, the Modi government has two choices. It can let it fester, expand into a larger political war. Or it can cut its losses and, as the Americans say, get off the kerb.

Here is the evidence that lets us say that the Modi government has lost the battle for these farm laws.

You see even a Modi-Shah BJP is unlikely to risk reopening this front at that point. In fact, the bellwether heartland state elections, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan, will be exactly 12 months away. Two of them have strong Congress incumbents and in the third, the BJP has bought and stolen power. Nobody’s risking losing these to make their point over farm reforms. These laws, then, are as bad as dead in the water.

Again, unilaterally, the government has already made a commitment of continuing with Minimum Support Price (MSP), although there is nothing in the laws saying it will be taken away. With so much already given away, the battle over the farm laws is lost.

The Modi government’s challenge now is to buy normalcy without making it look like a defeat. We know that it got away with one such, with the new land acquisition law. But that issue was still confined to Parliament. This is on the streets, highway choke-points, and in the expanse of wheat and paddy all around Delhi. This can spread. If the government retreats in surrender, this issue may close, but politics will rage. And why not? What is democracy but competitive politics, brutal, fair and fun? The next targets will then be other reform measures, from the new labour laws to the public listing of LIC.

What are the errors, or blunders, that brought India’s most powerful government in 35 years here? I shall list five:

1. Bringing in these laws through the ordinance route was a blunder. I speak from 20/20 hindsight, but then I am a commentator, not a political leader. To usher in the promise of sweeping change affecting the lives of more than half a billion people, the correct way would have been to market the ideas first. We don’t know if Narendra Modi now regrets not having prepared the ground for it. But the fact is, people at the mass level would be suspicious of such change through ordinances. Especially if you aren’t talking to them.

2. The manner in which the laws were pushed through Rajya Sabha added to these suspicions. This needed better parliamentary craft than the blunt use of vocal chords. This helped fan the fire, or spread the ‘hawa’ that something terrible was being forced down the surplus-producing farmers’ throats.

3. The party was riding far too high on its majority to care about allies and friends. If it had taken them along respectfully, the passage through Rajya Sabha wouldn’t have been so ungainly. At least the Akalis should never have been lost. But, as we’ve said before, this BJP does not understand Punjab or the Sikhs.

4. It also underestimated the frustration among the Jats of Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh, disempowered by the Modi-Shah politics. The senior-most Jat leaders in the Modi council of ministers are both inconsequential ministers of state. One is from distant Barmer in Rajasthan. The most visible of them, Sanjeev Balyan, won from Muzaffarnagar, where the big pro-Tikait mahapanchayat was held. In Haryana, the BJP has no Jat who counts. On the contrary, it found the marginalisation of Jat power as its big achievement. It refused to learn even from statewide, violent Jat agitations for reservations. The anger then was rooted in political marginalisation, as it is now. Ask why the BJP’s Jat ally Dushyant Chautala, or any of its Jat MPs/MLAs in UP, especially Balyan, are not on the ground, marketing these reforms? They wouldn’t dare.

5. The BJP conceded too much, too soon, unilaterally in the negotiations. It doesn’t have much more to give now. And the farm leaders have conceded nothing.

In conclusion, where does the Modi government go from here? One approach could be to tire the farmers out. On all evidence, that is not about to happen. Rabi harvest in April is still nearly 75 days away, and with much work done by mechanical harvesters and migrant workers, families would be quite capable of keeping the pickets full.

The next expectation would be that the Jats would ultimately make a deal. This is plausible. Note the key difference between Singhu and Ghazipur. In the first, no politician can even go for a selfie. Ask Ravneet Singh Bittu of the Congress, who was turned out unceremoniously. But everybody can go to Ghazipur and be photographed hugging Tikait. The Congress, Left, RLD, RJD, AAP, all of them. Even Sukhbir Singh Badal comes to Ghazipur, instead of Singhu to meet his fellow Sikhs from Punjab. Wherever there is politics and politicians, conflict resolution is possible. But what happens if this becomes a reality?

This will leave India and the Modi government with the most dangerous outcome of all. It will corner the Sikhs of Punjab. Already, the lousy barricading visuals and government’s prickly response to something as trivial as some celebrity tweets is threatening to redefine the issue from farm laws to national unity. The Modi government will err gravely if it changes the headline from farm protests to Sikh separatism.

This crisis requires political sophistication and governance skills. This BJP has neither. It has, instead, political skills and governance by clout, riding an all-conquering election-winning machine. It is the party’s inability to accept the realities of Indian politics and appreciate the limitations of a parliamentary majority that brought it here.

Does it have the smarts and sagacity to negotiate its way out of it? We can’t say. But we hope it does. Because the last thing India needs is to start another war for national unity. You would be nuts to reopen an issue in Punjab we all closed and buried by 1993.

Monday 11 January 2021

Tuesday 8 December 2020

Milton Friedman was wrong on the corporation

What should be the goal of the business corporation? For a long time, the prevailing view in English-speaking countries and, increasingly, elsewhere was that advanced by the economist Milton Friedman in a New York Times article, “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase Its Profits”, published in September 1970. I used to believe this, too. I was wrong.

Saturday 5 December 2020

Thatcher or Anna moment? Why Modi’s choice on farmers’ protest will shape future politics

Has the farmers’ blockade of Delhi brought Narendra Modi to his Thatcher moment or Anna moment? It is up to Modi to answer that question as India waits. It will write the course of India’s political economy, even electoral politics, in years to come.

For clarity, a Thatcher moment would mean when a big, audacious and risky push for reform, that threatens established structures and entrenched vested interests, brings an avalanche of opposition. That is what Margaret Thatcher faced with her radical shift to the economic Right. She locked horns with it, won, and became the Iron Lady. If she had given in under pressure, she’d just be a forgettable footnote in world history.

--Also watch

Anna moment is easier to understand. It is more recent. It was also located in Delhi. Unlike Thatcher who fought and crushed the unions and the British Left, Manmohan Singh and his UPA gave in to Anna Hazare, holding a special Parliament session, going down to him on their knees, implicitly owning up to all big corruption charges. Singh ceded all moral authority and political capital.

By the time Anna returned victorious for the usual rest & recreation at the Jindal fat farm in Bangalore, the Manmohan Singh government’s goose had been cooked. Anna was victorious not because he got the Lokpal Bill. Because that isn’t what he and his ‘managers’ were after. Their mission was to destroy UPA-2. They succeeded. Of course, helped along by the spinelessness as well as guilelessness of the UPA.

Modi and his counsels would do well to look at both instances with contrasting outcomes as they confront the biggest challenge in their six-and-a-half years. Don’t compare it with the anti-CAA movement. That suited the BJP politically by deepening polarisation; this one does the opposite. It’s a cruel thing to say, but you can’t politically make “Muslims” out of the Sikhs.

That “Khalistani hand” nonsense was tried, and it bombed. It was as much of a misstep as leaders of the Congress calling Anna Hazare “steeped in corruption, head to toe”. Remember that principle in marketing — nothing fails more spectacularly than an obvious lie. As this Khalistan slur was.

The anti-CAA movement involved Muslims and some Leftist intellectual groups. You could easily isolate and even physically crush them. We are merely stating a political reality. The Modi government did not even see the need to invite them for talks. With the farmers, the response has been different.

Besides, this crisis has come on top of multiple others that are defying resolution. The Chinese are not about to end their dharna in Ladakh, the virus is raging and the economy, downhill for six quarters, has been in a free fall lately. Because politically, economically, strategically and morally the space is now so limited, this becomes the Modi government’s biggest challenge.

Also read: Shambles over farmers’ protest shows Modi-Shah BJP needs a Punjab tutorial

Modi has a complaint that he is given too little credit as an economic reformer. That he has brought in the bankruptcy law, GST, PSU bank consolidation, FDI relaxations and so on, but still too many people, especially the most respected economists, do not see him as a reformer.

There is no denying that he has done some political heavy lifting with these reformist steps. But some, especially GST, have lost their way because of poor groundwork and execution. And certainly, all that the sudden demonetisation did was to break the economy’s momentum. His legacy, so far, is of slowing down and then reversing India’s growth.

Having inherited an economy where 8 per cent growth was the new normal, now RBI says it will be 8 per cent, but in the negative. It isn’t the record anybody wanted in his seventh year, with India’s per capita GDP set to fall below Bangladesh’s, according to an October IMF estimate.

The pandemic brought Modi the “don’t waste a crisis” opportunity. If Narasimha Rao and Manmohan Singh with a minority government could use the economic crisis of 1991 to carve out a good place for themselves in India’s economic history, why couldn’t he now? That is how a bunch of audacious moves were announced in a kind of pandemic package. The farm reform laws are among the most spectacular of these. Followed by labour laws.

This is comparable now to the change Margaret Thatcher had dared to bring. She wasn’t dealing with multiple other crises like Modi now, but then she also did not have the kind of almost total sway that Modi has over national politics. Any big change causes fear and protests. But this is at a scale that concerns 60 per cent of our population, connected with farming in different ways. That he and his government could have done a better job of selling it to the farmers is a fact, but that is in the past.

The Anna movement has greater parallels, physically and visually, with the current situation. Like India Against Corruption, the farmers’ protest also positions itself in the non-political space, denying its platform to any politician. Leading lights of popular culture are speaking and singing for it. Again, there is widespread popular sympathy as farmers are seen as virtuous, and victims. Just like the activists. Its supporters are using social media just as brilliantly as Anna’s.

Also read: How protesting farmers have kept politicians out of their agitation for over 2 months

There are some differences too. Unlike UPA-2, this prime minister is his own master. He doesn’t need to defer to someone in another Lutyens’ bungalow. He has personal popularity enormously higher than Manmohan Singh’s, great facility with words and a record of consistently winning elections for his party.

But this farmers’ stir looks ugly for him. His politics is built so centrally on the pillar of “messaging” that pictures of salt-of-the-earth farmers with weather-beaten faces, cooking and sharing ‘langars’, offering these to all comers, then refusing government hospitality at the talks and eating their own food brought from the gurdwara while sitting on the floor, and the widespread derision of the “Khalistani” charge is just the kind of messaging he doesn’t want. In his and his party’s scheme of things, the message is the politics.

Thatcher had no such issues, and Manmohan Singh had no chips to play with. How does Modi deal with this now? The temptation to retreat will be great. You can defer, withdraw the bills, send them to the select committee, embrace the farmers and buy time. It isn’t as if the Modi-Shah BJP doesn’t know how to retreat. It did so on the equally bold land acquisition bill, reeling under the ‘suit-boot ki sarkar’ punch. So, what about another ‘tactical retreat’?

It will be a disaster, and worse than Manmohan Singh’s to the Anna movement. At the heart of Modi’s political brand proposition is a ‘strong’ government. It was early days when he retreated on the land acquisition bill. The lack of a Rajya Sabha majority was an alibi. Another retreat now will shatter that ‘strongman’ image. The opposition will finally see him as fallible.

At the same time, farmers blockading the capital makes for really bad pictures. These aren’t nutcases of ‘Occupy Wall Street’. Farmers are at the heart of India. Plus, they have the time. Anybody with elementary familiarity with farming knows that once wheat and mustard, which is most of the rabi crop in the north, is planted, there isn’t that much to do until early April.

You can’t evict them as in the many Shaheen Baghs, and you can’t let them hang on. Even a part surrender will finish your authority. Because then protesters against labour reform will block the capital. That’s why how Modi answers this Thatcher or Anna moment question will determine national politics going ahead. Our wish, of course, is that he will choose Thatcher over Anna. It will be a tragedy if even Modi were to lose his nerve over his boldest reforms.

Sunday 19 July 2020

India: Where does one turn when law, political parties and the state turn their back on justice?

Anand Teltumbde, one of India’s important and courageous thinkers, just turned 70 in prison. He, along with Sudha Bharadwaj and others, is being held in the Bhima Koregaon case. They are being repeatedly denied bail. Varavara Rao, poet and Maoist intellectual, contracted COVID and has been subject to degrading and humiliating conditions at the age of 80. The overwhelming power that the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act gives to the state, the sheer impunity with which government can treat this group of accused, the Kafkaesque role of the judiciary in denying bail and making procedural safeguards ineffective, and the deafening political silence on their detention, all warrant deeper reflection. The accused in the Bhima Koregaon case are not the first to be victimised in this way; and they will not be the last. The UAPA is being used to target protest from Assam to Delhi.

Anand Teltumbde’s work, particularly “Republic of Caste”, presciently forecast his own condition. He, like the others, has drawn support from the usual petition-writing crowd of intellectuals. But his case provides a disturbing window on the political loneliness of a genuine intellectual in Indian conditions.

Here is a well-known Dalit intellectual being put in prison and yet no serious political protest, even from Dalit politicians. Teltumbde had, in another context written, “When Sudhir Dhawale, a Dalit activist, was arrested in 2011 on the trumped up charge of being a Naxalite and incarcerated for nearly four years, there was hardly any protest from the community.” This phenomenon of figures like Teltumbde not drawing broader political support requires some reflection. Teltumbde himself, in part, attributed this to divisions amongst Dalits, and their greater faith in the state. But his work points towards a subtler reason.

For all of India’s handwringing, that we need to escape identity politics, there is a great antipathy to anyone who tries to escape it. Teltumbde is one of those rare figures who argued that the Left and liberals failed to take caste seriously, and caste mobilisation failed to take class and economics seriously. But the result is a kind of suspension in between two constructions: Most of society does not get outraged because he is often reduced to being a Dalit intellectual; Dalits don’t get outraged because he becomes a “Left” intellectual. The blunt truth is that, if we leave the rarefied world of petitions, the only modality of protest that is politically effective is the one that has the imprimatur of community mobilisation behind it. If you can show a community identity is affected, all hell will break loose; without it, there is no political protest.

Teltumbde was also prescient about the way the term “Left” is used in India. Teltumbde himself is closer to the Left in his economic imagination. But the rhetorical function of the “Left” in India is not to describe the contest over the free market versus the state. The rhetorical function of the “Left” is to describe any ideological or political current that, while recognising the importance of identity, wants to escape its compulsory or simplistic character; so any broadly liberal position or a position that distances itself from “my community right or wrong” also becomes Left. For Hindutva, anyone who resists or transcends the narcissisms of collective identity becomes “Left.” But the same is increasingly true of other identities — Maratha, Jat, Dalit, Rajput. “Left” is anyone who complicates identity claims. That, rather than secular versus communal, is the big chasm in Indian politics. But the result is that if you are labelled “Left” in this way, you will have no political protection.

The charge of Maoism is the hyper version of this “Left” in the context of Adivasi mobilisation. Which is why the entire political class, and so much of India’s discursive space, keeps invoking the “Left” spectre. And Teltumbde was insightful in thinking that once you had been labelled Left in India, it was easy to secure a diminution in your legal and cultural standing. Even the Courts will turn off their thinking cap. It is in this that the genuine intellectual enterprise is a lonely one, whose disastrous political consequences Teltumbde is facing.

The Bhima Koregaon cases also throw a spotlight on so many state institutions. The UAPA, and its ubiquitous use is a travesty in a liberal democracy. The lawyer, Abhinav Sekhri, has, in a recent article (“How the UAPA is perverting the Idea of Justice”, Article14.com) pointed out two basic issues with the law. The law is designed in a way that it makes the question of innocence or guilt almost irrelevant. It can, in effect, inflict punishment without guilt. The idea that people like Teltumbde or the exemplary Bharadwaj cannot even get bail underscores this point. And second, the safeguards of our criminal justice process work unevenly at the best of times. But in the case of the UAPA, the courts have often, practically, suspended serious scrutiny of the state. What legitimises this conduct of the court is two things: The broader ideological construction of the “Left” as an existential threat. And the impatience of society with procedural safeguards. The UAPA has in some senses become the judicial version of the encounter — where the suspension of the normal meaning of the rule of law is itself seen as a kind of justice.

The state has been going after Varavara Rao for his entire life. He is a complicated figure. He is an extraordinarily powerful poet who made visible the exploitative skeins of Indian society; his poetry, even in translation, cannot fail to move you out of a complacent slumber. He was formidable in consciousness raising. Of this group, his ideological excusing of horrendous Maoist excesses, has been indefensible and disturbing. His moral stance once promoted a deeply meditative critique on the morality of revolutionary violence by Apoorvanand (“‘Our’ Violence Versus ‘Their’ Violence”, Kafila.online).

But the farce that the Indian state is enacting in pursuing Varavara Rao in the Bhima Koregaon prosecutions is proving him correct in two ways. First, in his insistence that what is known as bourgeois law is a sham in its own terms; the rule of law indeed is rule by law. And second, that repression and degradation is indeed the argument of a despotic state. Where does one turn when law, political parties and the state turn their back on justice?

Monday 11 May 2020

Why some companies will survive this crisis and others will die

The first written document about a Stora operation, a Swedish copper mine, dates back to 1288. Since then, the company — now Finland-based paper, pulp and biomaterials group Stora Enso — has endured through attempts to end its independence, the turmoil of the Reformation and industrial revolution, wars, regional and global, and now a pandemic.

“It would have been catastrophic for [Stora] to concentrate on its business in an introverted fashion, oblivious to politics. Instead the company reshaped its goals and methods to match the demands of the world outside,” writes Arie de Geus, describing one particularly turbulent era in the 15th century in his 1997 book The Living Company, shaped round a study of the world’s oldest companies he conducted for Royal Dutch Shell.

This is wisdom that companies today, wondering how to survive, let alone thrive, could use. Alas, de Geus himself is not around to help them: he died in November last year.

Part of his work lives on through the scenario-planning exercises that I identified last week as one way of advancing through the uncertainty ahead. The multilingual thinker was Shell’s director of scenario planning, where he developed the distinction between potential futures (in French, “les futurs”) and what was inevitably to come (“l’avenir”).

He also lived through the aftermath of the second world war, which destroyed Rotterdam, the city of his birth, and encouraged him and his friends to seek jobs within the safe havens of great corporate institutions, such as Shell, Unilever and Philips.

It is not a given that all the oldest or largest companies will outlive this crisis. Those that do, however, should take a leaf out of de Geus’s book.

Longtime collaborator and friend Göran Carstedt, a former Volvo and Ikea executive, says he discussed with de Geus last year how near-death experiences enhance the appreciation of being alive. “Things come to the fore that we took for granted. You start to see the world through the lens of the living,” he told me. “Arie liked to say, ‘people change and when they do, they change the society in which they live’.” That went for companies as much as for societies. Long-lived groups such as Stora owed their survival to their adaptability as human communities and their tolerance for ideas, as much as to their financial prudence.

These are big ideas for business leaders to ponder at a time when most are desperately trying to keep their heads above the flood or, at best, concentrating on the practicalities of how to restart after lockdown. In her latest update last month, Stora Enso’s chief executive sounded as preoccupied by pressing questions of temporary lay-offs, travel bans and capital expenditure reductions as her peers at companies with a shorter pedigree.

Some groups that meet de Geus’s common attributes for longevity are still likely to go under, simply because they find themselves exposed to the wrong sector at the wrong time.

Others, though, will find they are ill-equipped for the aftermath. What he called “intolerant” companies, which “go for maximum results with minimum resources”, can live for a long time in stable conditions. “Profound disruptions like this will simply reveal the underlying schisms that were already there,” the veteran management thinker Peter Senge, who worked with de Geus, told me via email. “Those who were on a path toward deep change will find ways to use the forces now at play to carry on, and even expand. Those who weren’t, won't.” For him the core question is whether those who interpret the pandemic as a signal that humans need to change how they live will grow to form a critical mass.

For decades after the war, big companies did not change the way they operated. They took advantage of young people who believed material security was “worth the price of submitting to strong central leadership vested in relatively few people”, de Geus wrote. Faced with this crisis, though, de Geus would have placed his confidence in those companies that had evolved a commitment to organisational learning and shared decision-making, according to another close collaborator, Irène Dupoux-Couturier.

The pressure of this crisis is already flattening decision-making hierarchies. Progress out of the pandemic will be founded on technology that reinforces the human community by encouraging rapid cross-company collaboration.

De Geus was adamant that a true “living company” would divest assets and change its activity before sacrificing its people, if its survival was at stake. That optimism is bound to be tested in the coming months but it is worth clinging to.

“Who knows if the characteristics of Arie’s long-lived companies . . . boost resilience in such situations as this?” Mr Senge told me. “But it is hard to see them lessening it.”

Saturday 7 March 2020

150 years of data proves it: Strongmen are bad for the economy

As governments around the world gravitate toward rightwing populist and authoritarian leaders, many have pointed to the 2008 global recession and the economic hardship that followed as the reason.

Take America, for instance: According to many analysts, the rise of US president Donald Trump has to be seen in relation to the great recession, and was aided by a frustrated working and middle class that saw in his election the promise of new economic wellbeing.

This repeats a historical pattern: When facing dire straits, populations tend to delegate responsibility and look for a leader who can (or at least promise to) get them back to better times.

It’s a bad idea, however, and not just for democracy: It’s terrible for the economy, too.

A study by researchers of the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology and Victoria University in Melbourne published in Leadership Quarterly looked at economic data in relation to the performances of authoritarian leaders versus democratic governments.

The authors analyzed the governments of 133 countries between 1858 to 2010, and found that autocrats were either damaging or inconsequential for the economy of their countries. Besides showing the poor economic outcomes of oppressive regimes, the study calls into question the idea of “benevolent dictators”—for instance Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew or Rwanda’s Paul Kagame—who are commonly believed to be good for the economy.

“Autocrats with positive effects are found at best as frequently as predicted by chance, while autocrats with negative effects are found in abundance,” wrote Stephanie Rizio and Ahmed Skali, the authors of the paper. Strongmen mostly leave a county’s economy worse than they found it, or simply “ride the wave” of an economic growth that would have happened regardless of their rule.

The researchers used data from the Archigos dataset of leaders, which lists both the leaders of countries and the person with the most power in a country at any given time. The official head of state might sometimes be no more than a figurehead, while someone else holds the actual power. For instance, the paper notes that Septimus Rameau was the de-facto ruler of Haiti between 1874 and 1876, while his uncle Michel Domingue was the official leader; or Ziaur Rahman, who was actually in charge of Bangladesh between 1975 and 1977, while Abu Sadat Mohammad Sayem was the country’s official leader.

---Also watch

The data was then cross-referenced with the Polity IV dataset, which establishes the kind of political government in place for 185 countries every year, defining whether the country is a democracy or an autocracy. For each year, countries are scored from 1 to 10. Scores below 6 indicate an autocratic regime, while democracies stand above six.

To analyze the economic outcome of a strongman’s rule, the researches looked at per capita GDP. The researchers then compared economic growth in countries with autocratic regimes to economic growth in democracies, looking at whether the impact of the autocrats (and the democratic leaders) was relevant—or if the results were ascribable simply to chance.

In the large majority of cases, countries led by autocrats—whether benevolent or otherwise—were found to have worse economic outcomes in terms of growth than democracies. And not just in the short term: The researchers also looked at delayed growth, testing the hypothesis that reforms put in place by a dictator might take time to bear fruit. They found no demonstrable growth to connect with autocratic rule.

Growth isn’t the only economic metric on which autocrats failed to deliver. They also fell short on employment, health and education spending, and government debt.

But—in what is possibly good news for Trump, who is facing the threat of another recession—while it seems people are inclined to vote a strongman into power to fix their economic woes, they aren’t as quick to get rid of him if the economy doesn’t improve. The paper found that while authoritarians do pay for their bad economic performances, it takes much longer for them to lose popular support and be deposed from power than they do in a democracy under comparable economic circumstances.

Skali told Quartz the research didn’t look into the relation between economic hardship and the rise of autocracies, and why distressed populations gravitate towards strongmen. But he did share a speculation: In times of hardship, primates tend to accept, and follow, the authority of an alpha male.