A handy guide to sorcery and superstitions in modern leadership

ANDREW HILL in the FT

It has been a while since a UK company was accused of sorcery.

Congratulations, then, to evolutionary biologist Sally Le Page for triggering just such a charge last week. She blogged her astonishment that many of the country’s biggest water companies had blithely admitted to using dowsing rods to help locate pipes and leaks. Another scientist has dismissed the technique as witchcraft.

The water suppliers themselves have been rowing back fast. Some engineers were part-time diviners, apparently, but the real hard work of leak detection was backed by drones, robots and lots and lots of science.

I say let us allow the water industry’s warlocks to indulge their medieval pastimes. After all, there are plenty of examples of modern management and leadership based on superstition, credulity and blind faith. Here are just a few:

Numerology. In China, mumbo-jumbo about feng shui and ominous or propitious flotation dates, trading symbols and stock codes often influences how supposedly sophisticated companies arrange their affairs. Elements of Alibaba’s 2014 listing appeared to revolve around the “lucky” number eight, for example.

But before western chief executives scoff, they should consider how much they are still in thrall to the cult described in Alex Berenson’s 2003book The Number — the quarterly earnings consensus they conspire with analysts and investors to hit, or better still, to beat. Regular evidence — recently, for instance, from Campbell Soup (a miss), and Home Depot (a “beat”) — suggests the cult is thriving.

Indeed, the availability and crunchability of Big Data have broadened disciples of the number. They now include company bosses who worship near-term, data-driven answers, rather than holding out for better, if messier, longer-term solutions that take account of human intuition.

As the veteran management thinker Charles Handy pointed out in a rousing closing address to the recent Drucker Forum, “if the organisation were purely digitised . . . it would be a very dreary place, a prison for the human soul”.

Leaps of faith. Any chief executive who has ever announced a corporate vision without a clear idea of the kinds of steps needed to achieve the goal is at least partly guilty of magical thinking.

Richard Rumelt wrote in Good Strategy/Bad Strategy about the dangerous delusion that aiming for success can lead to success: “I would not care to fly in an aircraft designed by people who focused only on an image of a flying aeroplane and never considered modes of failure.”

Throw a coin and make a wish. Modern companies still close their eyes to evidence suggesting bonuses are at best a blunt incentive, and chuck cash at staff in the hope that it will help them reach their heart’s desire. At least wishing wells swallow the donation with no adverse consequence, other than the loss of your penny. Unfettered bonus culture, as the worst excesses of the financial crisis suggest, can backfire in unexpected ways.

Chants and mantras. Slavishly applied governance codes and regulations help box-ticking compliance staff and board members sleep easy, by absolving them of the need to make difficult judgments. Meaningless mission statements give executives a mantra to recite as cover for not actually putting their values into practice.

Human sacrifice. Restructurings and lay-offs are the modern ritual for appeasing the gods (but without the benefits of bringing the community together for a bit of a celebration).

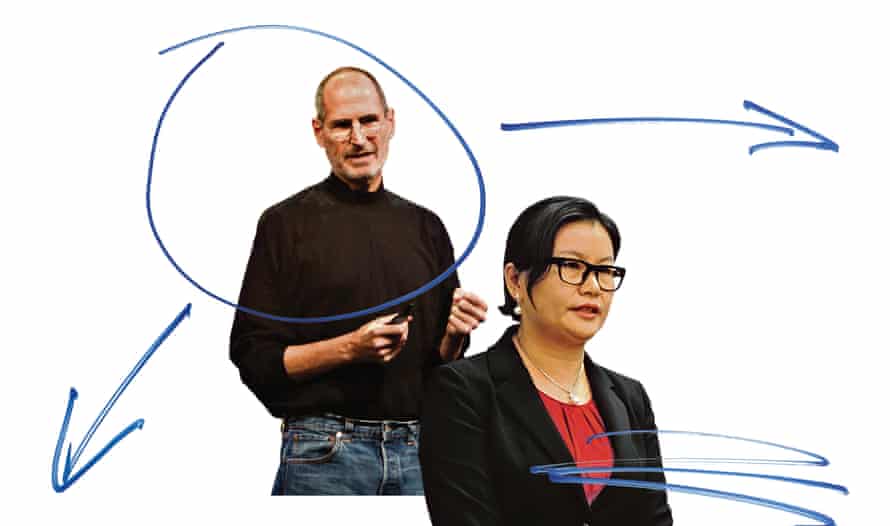

Hero worship. For all the modish talk of flat hierarchies and distributed leadership, chief executives still become the central figures in a myth that is largely of their own creation.

The most dangerous part of this self-delusion is that they believe success was achieved entirely through their “skill, preparation and tenacity”, as described by Jim Collins and Morten Hansen in Great by Choice.

The researchers found successful leaders could generate a greater “return on luck” by being more disciplined at exploiting opportunities and riding bad luck to make themselves stronger. But they pointed out there was a fine line between the best leaders and those who put their organisations at risk through an exaggerated and dangerous belief in their own powers. Such leaders had a tendency to make these sorts of assertions: “Luck played no role in my success — I’m just really good.”

Here is where humble deference to unpredictable and poorly understood outside forces would be healthy. If nothing else, over-confident leaders should be reminded that their destiny is sometimes out of their hands.