'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Saturday, 19 November 2022

Wednesday, 12 October 2022

Thursday, 30 June 2022

Scientific Facts have a Half-Life - Life is Poker not Chess 4

Abridged and adapted from Thinking in Bets by Annie Duke

The Half-Life of Facts, by Samuel Arbesman, is a great read about how practically every fact we’ve ever known has been subject to revision or reversal. The book talks about the extinction of the coelacanth, a fish from the Late Cretaceous period. This was the period that also saw the extinction of dinosaurs and other species. In the late 1930s and independently in the mid 1950s, coelacanths were found alive and well. Arbesman quoted a list of 187 species of mammals declared extinct, more than a third of which have subsequently been discovered as un-extinct.

Given that even scientific facts have an expiration date, we would all be well advised to take a good hard look at our beliefs, which are formed and updated in a much more haphazard way than in science.

We would be better served as communicators and decision makers if we thought less about whether we are confident in our beliefs and more about how confident we are about each of our beliefs. What if, in addition to expressing what we believe, we also rated our level of confidence about the accuracy of our belief on a scale of zero to ten? Zero would mean we are certain a belief is not true. Ten would mean we are certain that our belief is true. Forcing ourselves to express how sure we are of our beliefs brings to plain sight the probabilistic nature of those beliefs, that we believe is almost never 100% or 0% accurate but, rather, somewhere in between.

Incorporating uncertainty in the way we think about what we believe creates open-mindedness, moving us closer to a more objective stance towards information that disagrees with us. We are less likely to succumb to motivated reasoning since it feels better to make small adjustments in degrees of certainty instead of having to grossly downgrade from ‘right’ to ‘’wrong’. This shifts us away from treating information that disagrees with us as a threat, as something we have to defend against, making us better able to truthseek.

There is no sin in finding out there is evidence that contradicts what we believe. The only sin is in not using that evidence as objectively as possible to refine that belief going forward. By saying, ‘I’m 80%’ and thereby communicating we aren’t sure, we open the door for others to tell us what they know. They realise they can contribute without having to confront us by saying or implying, ‘You’re wrong’. Admitting we are not sure is an invitation for help in refining our beliefs and that will make our beliefs more accurate over time as we are more likely to gather relevant information.

Acknowledging that decisions are bets based on our beliefs, getting comfortable with uncertainty and redefining right and wrong are integral to a good overall approach to decision making.

Monday, 30 May 2022

On Fact, Opinion and Belief

Annie Duke in 'Thinking in Bets'

What exactly is the difference between fact, opinion and belief?” .

Fact: (noun): A piece of information that can be backed up by evidence.

Belief: (noun): A state or habit of mind, in which trust or confidence is placed, in some person or thing. Something accepted or considered to be true.

Opinion: (noun): a view, judgement or appraisal formed in the mind about a particular matter.

The main difference here is that we can verify facts, but opinions and beliefs are not verifiable. Until relatively recently, most people would call facts things like numbers, dates, photographic accounts that we can all agree upon.

More recently, it has become commonplace to question even the most mundane objective sources of fact, like eyewitness accounts, and credible peer-reviewed science, but that is a topic for another day.

How we think we form our beliefs:

We hear something;

We think about it and vet it, determining whether it is true or false; only after that

We form our belief

Actually, we form our beliefs:

We hear something;

We believe it to be true;

Only sometimes, later, if we have the time or the inclination, we think about it and vet it, determining whether it is, in fact, true or false.

Psychology professor Daniel Gilbert, “People are credulous creatures who find it very easy to believe and very difficult to doubt”.

Our default is to believe that what we hear and read is true. Even when that information is clearly presented as being false, we are still likely to process it as true.

For example, some people believe that we use only 10% of our brains. If you hold that belief, did you ever research it for yourself?

People usually say it is something they heard but they have no idea where or from whom. Yet they are confident that this is true. That should be proof enough that the way we form beliefs is foolish. And, we actually use all parts of our brain.

Our beliefs drive the way we process information. We form beliefs without vetting/testing most of them and we even maintain them even after receiving clear, corrective information.

Once a belief is lodged, it becomes difficult to dislodge it from our thinking. It takes a life of its own, leading us to notice and seek out evidence confirming our belief. We rarely challenge the validity of confirming evidence and ignore or work hard to actively discredit information contradicting the belief. This irrational, circular information-processing pattern is called motivated reasoning.

Truth Seeking, the desire to know the truth regardless of whether the truth aligns with the beliefs we currently hold, is not naturally supported by the way we process information.

Instead of altering our beliefs to fit new information, we do the opposite, altering our interpretation of that information to fit our beliefs.

Fake news works because people who already hold beliefs consistent with the story generally won’t question the evidence. The potency of fake news is that it entrenches beliefs its intended audience already has, and then amplifies them. Social media is a playground for motivated reasoning. It provides the promise of access to a greater diversity of information sources and opinions than we’ve ever had available. Yet, we gravitate towards sources that confirm our beliefs, that agree with us. Every flavour is out there, but we tend to stick with our favourite.

Even when directly confronted with facts that disconfirm our beliefs, we don’t let facts get in the way of our opinions.

Being Smart Makes It Worse

The popular wisdom is that the smarter you are, the less susceptible you are to fake news or disinformation. After all, smart people are more likely to analyze and effectively evaluate where the information is coming from, right? Part of being ‘smart’ is being good at processing information, parsing the quality of an argument and the credibility of the source.

Surprisingly, being smart can actually make bias worse. The smarter you are, the better you are at constructing a narrative that supports your beliefs, rationalising and framing the data to fit your argument or point of view.

Unfortunately, this is just the way evolution built us. We are wired to protect our beliefs even when our goal is to truthseek. This is one of the instances where being smart and aware of our capacity for irrationality alone doesn’t help us refrain from biased reasoning. As with visual illusions, we can’t make our minds work differently than they do no matter how smart we are. Just as we can’t unsee an illusion, intellect or will power alone can’t make us resist motivated reasoning.

Wanna Bet?

Imagine taking part in a conversation with a friend about the movie Citizen Kane. BEst film of all time, introduced a bunch of new techniques by which directors could contribute to storytelling. “Obviously, it won the best picture Oscar,” you gush, as part of a list of superlatives the film unquestionably deserves.

Then your friend says,”Wanna bet?”

Suddenly, you’re not so sure. That challenge puts you on your heels, causing you to back off your declaration and question the belief that you just declared with such assurance.

When someone challenges us to bet on a belief, signalling their confidence that our belief is inaccurate in some way, ideally it triggers us to vet the belief, taking an inventory of the evidence that informed us.

How do I know this?

Where did I get this information?

Who did I get it from?

What is the quality of my sources?

How much do I trust them?

How up to date is my information?

How much information do I have that is relevant to the belief?

What other things like this have I been confident about that turned out not to be true?

What are the other plausible alternatives?

What do I know about the person challenging my belief?

What is their view of how credible my opinion is?

What do they know that I don’t know?

What is their level of expertise?

What am I missing?

Remember the order in which we form our beliefs:

We hear something;

We believe it to be true;

Only sometimes, later, if we have the time or the inclination, we think about it and vet it, determining whether it is, in fact, true or false.

“Wanna bet?” triggers us to engage in that third step that we only sometimes get to. Being asked if we are willing to bet money on it makes it much more likely that we will examine our information in a less biased way, be more honest with ourselves about how sure we are of our beliefs, and be more open to updating and calibrating our beliefs.

A lot of good can result from someone saying, “Wanna bet?” Offering a wager brings the risk out in the open, making explicit what is implicit (and frequently overlooked). The more we recognise that we are betting on our beliefs (with our happiness, attention, health, money time or some other limited resource), the more we are likely to temper our statements, getting closer to the truth as we acknowledge the risk inherent in what we believe.

Once we start doing this (at the risk of losing friends), we are more likely to recognise that there is always a degree of uncertainty, that we are generally less sure than we thought we were, that practically nothing is black and white 0% or 100%. And that's a pretty good philosophy for living.

Saturday, 23 April 2022

The state of Pakistan: Isn't the support for BJP similar?

Fahd Hussain in The Dawn

Imran Khan’s supporters can see no wrong in what he says or does. We have witnessed this phenomenon unfurl itself like a lazy python these last few years, but more so with greater intensity during Khan’s pre- and post-ouster days. On display is a textbook case of blind devotion. Such devotion entails a deliberate — or perhaps subconscious — suspension of critical thinking. Only mass hysteria can explain absolute rejection of facts and a willing embrace of free-flying rhetoric untethered by verifiable information.

And yet, does this really make sense?

Bounce this explanation off actual people around you — friends, families, acquaintances — and you start to feel uncomfortable with the laziness of the explanation.

On your left, for instance, is the professor with a doctorate in natural sciences from one of the top universities in the world, someone whose entire educational foundation and career is based on the power of empirical evidence and scientific rationalism — and here he is hysterically arguing why the PTI deputy speaker’s violation of the constitution is no big deal. On your right is the top executive of a multinational company with an MBA from an Ivy League school, someone whose training and practice of craft is based on hard data crunched with power of sharp logic — and here he is frothing at the mouth in delirium while yelling that the Joe Biden administration actually conspired with the entire top leadership of the PDM to topple Imran Khan.

These are rational people, you remind yourself. You have known them for years, and admired them for their academic and professional achievements — perhaps even been motivated by their pursuit of success — and yet you see them experiencing a strange quasi-psychedelic meltdown in full public glare. It just does not add up.

It is not just these metaphorical persons — resembling many real ones in all our lives, as it so happens — but hundreds of thousands of Pakistanis from all walks of life locked inside a massive groupthink spurred by sweeping generalisations dressed up as political narrative. No argument, no logic and no rationale — no, nothing makes sense, and nothing is acceptable or even worth considering if it does not gel perfectly with their preconceived notions.

What we are witnessing is a seminal moment in our political evolution — progressive or regressive is a matter of personal perspective — and this moment is situated bang in the centre of a social and political transformation so impactful that it could define the shape of our society for the years ahead.

In an acutely polarised environment, it is easy to pass judgement on those sitting across the fence. Most of us yield to this temptation. When we do, we help reinforce caricatures that have little resemblance to people around us, and these fail to explain why people believe what they believe.

So why do such a large number of people believe what they believe even when overwhelming evidence points towards the opposite conclusion? In our context, this may be due in part to the visceral politicisation of the national discourse and the deep personal loathing of rivals that the PTI has injected into what should otherwise be a contest of ideas and ideologies. At the heart of this is the revulsion against the system because it has not really delivered what it exists to deliver: improving the lives of citizens through protection of rights and provision of services. It is therefore easy and convenient to blame the system, and in turn all those institutions that constitute the system as a whole.

Imran Khan has modelled himself well as the anti-system crusader. He insists very persuasively that he has neither been co-opted nor corrupted by the system; that when he says he wants to change this system, it implies that there is nothing sacrosanct about the system, or for that matter, about the exalted institutions that make up the system. He has been able to establish this narrative successfully because the central theme of his narrative is, in fact, true: the system has not delivered.

But the argument is only half done here. The other half is perhaps even more crucial — diagnosing why it has not delivered. It is here that Imran Khan goes off tangent. And he does so not just in terms of his solutions, but his own shockingly weak performance as the prime minister who had it all but could not do much with it. In fact, after nearly four years in power, and having precious little to show for them, Imran has for all practical purposes joined the long line of those who are, in fact, responsible for the sad reality that the system has not delivered.

But someone forgot to break this news to the PTI supporters.

In essence then, if Pakistani society wants to row itself back from this stage where the electorate is at war with itself on a battlefield littered with semi-truths, partial facts and outright lies, it will need to face up to a bitter fact: what we see unfolding in front of us is the contamination of decades of social and educational decay injected with deadly and potent steroids of propaganda, brainwashing and ‘otherisation’ of anyone who looks, speaks, acts or believes differently.

Those social studies books you read in school and thought you would outgrow — well, now you know how wrong you were?

In this cesspool, everyone points fingers at everyone else when no one really has the right to do so. Seven decades of wrong governance laced with wrong priorities and fuelled by wrong policies have led us to a stage today where traditional parties cannot stomach the aspirations of a new generation, and new parties cannot digest the requirements of what constitutes governance, statecraft and institutional equilibrium within a democratic society.

And you thought holding elections was our biggest problem today. Be afraid. Be very afraid.

Saturday, 5 February 2022

Fighting fake news with fact check has not been a successful project

During the debate over the motion of thanks to the President’s address in Parliament, Congress leader Rahul Gandhi made several good points in his speech. He raised critical issues like the importance of federalism, widespread joblessness, inequality, crony capitalism in India, and unfulfilled development promises. He also talked about the sacrifices made by his family and ancestors. Congress supporters as well as Left and liberal secularists are going gaga over Gandhi’s speech and talking in superlatives. This is fine.

Gandhi’s extempore speech, without the use of a teleprompter, was laced with conviction and courage.

But politics, unlike debating society, is not only about oratory and being convincing and logical or even about telling the truth. More so in India of today, where in Narendra Modi, Gandhi has an opponent whose claim to fame is his glorified ability to strike an emotional chord with the people.

Prime Minister Modi has made and is still making two sets of promises. One set of promises are for the larger audiences, those who are not in the BJP fold. The second set of Modi’s promises are for the BJP’s core voters, the insiders.

The written manifesto BJP’s isn’t bothered about

Let’s look at first set of promises as per the BJP’s 2014 Lok Sabha election manifesto.

1. Price Rise: Will stop hoarding and black marketing. Special courts to stop hoarding. Price stabilisation fund.

2. Employment: Jobs to 2 crore youth every year.

3. Health: Drinking water for all. AIIMS-like institutions in all states

4. Smart Cities: Will create 100 new smart cities with free wi-fi and world-class facilities

5. Housing: Pucca house for everyone by 2022

6. Infrastructure: Bullet train, freight corridors, Sagar Mala project, upgraded connectivity of Northeast and J&K with the rest of India.

7. Education: Raising public spending on education to 6 per cent of GDP. Establishing national e-library

8. Rural Development: Identifying 100 of the most backward districts and bringing them at par with developed districts

9. E-governance: Broadband connectivity in all villages. Digitalising all government records.

10. Women: 33 per cent reservation for women through constitutional amendment

11. Electoral reform: Electoral reforms to eliminate criminals. Evolve a method of holding Assembly and Lok Sabha elections simultaneously.

The BJP government started work on some of these promises and can also claim deliveries. But even the BJP does not make them poll issues anymore. It is hard to recall the last time any senior BJP leader even talked about these promises in political rallies.

My argument is that the BJP does not identify itself with these issues anymore. They are simply packaging material used for impression management.

So, when Rahul Gandhi talks about BJP’s failures in health, Make in India, education, employment, manufacturing sector or on mitigating inequality, he is hitting the BJP where it doesn’t hurt the party. The BJP is not even claiming to have performed in these fields. Whatever it has done are side shows that even the BJP does not believe in promoting.

So, what are the BJP’s main offerings? It is this question that brings us to the second set of BJP’s promises.

Unwritten promises the BJP is fulfilling

These are the promises that the party makes to its core constituencies, its faithful voters. These promises often don’t end up in the BJP’s election manifesto. The party goes into an unwritten agreement with its core voters, promising that these will be delivered, come what may. These promises are like construction of Ram Temple in Ayodhya, Kashi and Mathura, Uniform Civil Code, abrogation of Article 370, cow protection, ‘saving’ Hindu girls from the so-called “love jihad”, keeping Muslim ‘refugees’ in check, promoting Sanskrit, Yoga and Ayurveda, and so on and so forth.

The BJP has delivered on each of these promises. With the Triple Talaq law, it has delivered half of Uniform Civil Code, which is work in progress for the BJP. Kashi Corridor’s development has made Gyanvapi mosque almost invisible. The BJP has assuaged the sentiments of the Kashmiri Pandits and the Brahmins by dismantling the statehood and assembly of J&K. One can easily argue that these are not the real issues as they have nothing to do with people’s welfare, health, education, job or infrastructure.

But to say so will be an underestimation of India’s political reality. Consider this: there is almost zero possibility of someone in mainland India dying in a terror attack, and yet, the BJP can make fighting terrorism a big issue as we saw in the 2019 Lok Sabha election, when Modi-led BJP campaign played the Pulwama attack to the hilt. Any such attack is by and large a case of intelligence failure, but that argument was lost in the cacophony of counter attack and macho nationalism that Modi, BJP leaders and the media drove incessantly until the end of the election. In the 2019 Lok Sabha election, the biggest casualty was the BJP’s 2014 election manifesto. Nobody was interested in putting out a report card, assessing the government’s delivery on the promises it had made to register an unprecedented victory five years before.

You can’t fact-check emotions

In his book Nervous States, British political scientist William Davies argues, “Experts and facts no longer seem capable of settling arguments to the extent that they once did. Objective claims about the economy, society, the human body and nature can no longer be successfully insulated from emotions.” He cites various events in recent history to argue that the 17th century enlightenment ideas of experts and facts are now losing steam, and the institutions that should be beyond the fray of politics of sentiments and emotions are withering away.

In such a scenario, when emotions and feelings have become more overpowering, Rahul Gandhi is trying to become a fact-checker and a hermit who talks about GDP, growth and human development. He might be telling the truth, but will that sufficiently counter the emotional pitching of the BJP? We don’t have any template to answer this question, but fighting fake news with fact check has not been a successful project. If fake news confirms the ideas and emotions of an individual or a group, then it travels far and wide. Fact check, on the other hand, reaches a limited audience as it targets the thinking faculties and misses the feelings and emotions. And emotions will, and do, overwhelm the domain of truth on any given day.

Despite all the praises and claps Rahul Gandhi got for his fiery speech, his task remains quite difficult.

Journalist and editor William Davis has an advice, which can be useful for Rahul Gandhi and for all the rationalists and liberals — “Rather than denigrate the influence of feelings in society today, we need to get better at listening to them and learning from them. Instead of bemoaning the influx of emotions into politics, we should value democracy’s capacity to give voice to fear, pain and anxiety that might otherwise be diverted in far more destructive directions. If we’re to steer through the new epoch, and rediscover something more stable beyond it, we need, above all, to understand it.”

Friday, 4 February 2022

Sunday, 2 January 2022

Monday, 28 June 2021

Tuesday, 1 June 2021

If the Wuhan lab-leak hypothesis is true, expect a political earthquake

Thomas Frank in The Guardian

There was a time when the Covid pandemic seemed to confirm so many of our assumptions. It cast down the people we regarded as villains. It raised up those we thought were heroes. It prospered people who could shift easily to working from home even as it problematized the lives of those Trump voters living in the old economy.

Like all plagues, Covid often felt like the hand of God on earth, scourging the people for their sins against higher learning and visibly sorting the righteous from the unmasked wicked. “Respect science,” admonished our yard signs. And lo!, Covid came and forced us to do so, elevating our scientists to the highest seats of social authority, from where they banned assembly, commerce, and all the rest.

We cast blame so innocently in those days. We scolded at will. We knew who was right and we shook our heads to behold those in the wrong playing in their swimming pools and on the beach. It made perfect sense to us that Donald Trump, a politician we despised, could not grasp the situation, that he suggested people inject bleach, and that he was personally responsible for more than one super-spreading event. Reality itself punished leaders like him who refused to bow to expertise. The prestige news media even figured out a way to blame the worst death tolls on a system of organized ignorance they called “populism.”

But these days the consensus doesn’t consense quite as well as it used to. Now the media is filled with disturbing stories suggesting that Covid might have come — not from “populism” at all, but from a laboratory screw-up in Wuhan, China. You can feel the moral convulsions beginning as the question sets in: What if science itself is in some way culpable for all this?

*

I am no expert on epidemics. Like everyone else I know, I spent the pandemic doing as I was told. A few months ago I even tried to talk a Fox News viewer out of believing in the lab-leak theory of Covid’s origins. The reason I did that is because the newspapers I read and the TV shows I watched had assured me on many occasions that the lab-leak theory wasn’t true, that it was a racist conspiracy theory, that only deluded Trumpists believed it, that it got infinite pants-on-fire ratings from the fact-checkers, and because (despite all my cynicism) I am the sort who has always trusted the mainstream news media.

My own complacency on the matter was dynamited by the lab-leak essay that ran in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists earlier this month; a few weeks later everyone from Doctor Fauci to President Biden is acknowledging that the lab-accident hypothesis might have some merit. We don’t know the real answer yet, and we probably will never know, but this is the moment to anticipate what such a finding might ultimately mean. What if this crazy story turns out to be true?

The answer is that this is the kind of thing that could obliterate the faith of millions. The last global disaster, the financial crisis of 2008, smashed people’s trust in the institutions of capitalism, in the myths of free trade and the New Economy, and eventually in the elites who ran both American political parties.

In the years since (and for complicated reasons), liberal leaders have labored to remake themselves into defenders of professional rectitude and established legitimacy in nearly every field. In reaction to the fool Trump, liberalism made a sort of cult out of science, expertise, the university system, executive-branch “norms,” the “intelligence community,” the State Department, NGOs, the legacy news media, and the hierarchy of credentialed achievement in general.

Now here we are in the waning days of Disastrous Global Crisis #2. Covid is of course worse by many orders of magnitude than the mortgage meltdown — it has killed millions and ruined lives and disrupted the world economy far more extensively. Should it turn out that scientists and experts and NGOs, etc. are villains rather than heroes of this story, we may very well see the expert-worshiping values of modern liberalism go up in a fireball of public anger.

Consider the details of the story as we have learned them in the last few weeks:

- Lab leaks happen. They aren’t the result of conspiracies: “a lab accident is an accident,” as Nathan Robinson points out; they happen all the time, in this country and in others, and people die from them.

- There is evidence that the lab in question, which studies bat coronaviruses, may have been conducting what is called “gain of function” research, a dangerous innovation in which diseases are deliberately made more virulent. By the way, right-wingers didn’t dream up “gain of function”: all the cool virologists have been doing it (in this country and in others) even as the squares have been warning against it for years.

- There are strong hints that some of the bat-virus research at the Wuhan lab was funded in part by the American national-medical establishment — which is to say, the lab-leak hypothesis doesn’t implicate China alone.

- There seem to have been astonishing conflicts of interest among the people assigned to get to the bottom of it all, and (as we know from Enron and the housing bubble) conflicts of interest are always what trip up the well-credentialed professionals whom liberals insist we must all heed, honor, and obey.

- The news media, in its zealous policing of the boundaries of the permissible, insisted that Russiagate was ever so true but that the lab-leak hypothesis was false false false, and woe unto anyone who dared disagree. Reporters gulped down whatever line was most flattering to the experts they were quoting and then insisted that it was 100% right and absolutely incontrovertible — that anything else was only unhinged Trumpist folly, that democracy dies when unbelievers get to speak, and so on.

- The social media monopolies actually censored posts about the lab-leak hypothesis. Of course they did! Because we’re at war with misinformation, you know, and people need to be brought back to the true and correct faith — as agreed upon by experts.

“Let us pray, now, for science,” intoned a New York Times columnist back at the beginning of the Covid pandemic. The title of his article laid down the foundational faith of Trump-era liberalism: “Coronavirus is What You Get When You Ignore Science.”

Ten months later, at the end of a scary article about the history of “gain of function” research and its possible role in the still ongoing Covid pandemic, Nicholson Baker wrote as follows: “This may be the great scientific meta-experiment of the 21st century. Could a world full of scientists do all kinds of reckless recombinant things with viral diseases for many years and successfully avoid a serious outbreak? The hypothesis was that, yes, it was doable. The risk was worth taking. There would be no pandemic.”

Except there was. If it does indeed turn out that the lab-leak hypothesis is the right explanation for how it began — that the common people of the world have been forced into a real-life lab experiment, at tremendous cost — there is a moral earthquake on the way.

Because if the hypothesis is right, it will soon start to dawn on people that our mistake was not insufficient reverence for scientists, or inadequate respect for expertise, or not enough censorship on Facebook. It was a failure to think critically about all of the above, to understand that there is no such thing as absolute expertise. Think of all the disasters of recent years: economic neoliberalism, destructive trade policies, the Iraq War, the housing bubble, banks that are “too big to fail,” mortgage-backed securities, the Hillary Clinton campaign of 2016 — all of these disasters brought to you by the total, self-assured unanimity of the highly educated people who are supposed to know what they’re doing, plus the total complacency of the highly educated people who are supposed to be supervising them.

Then again, maybe I am wrong to roll out all this speculation. Maybe the lab-leak hypothesis will be convincingly disproven. I certainly hope it is.

But even if it inches closer to being confirmed, we can guess what the next turn of the narrative will be. It was a “perfect storm,” the experts will say. Who coulda known? And besides (they will say), the origins of the pandemic don’t matter any more. Go back to sleep.

Saturday, 1 May 2021

Sunday, 21 March 2021

DECODING DENIALISM

On November 12, 2009, the New York Times (NYT) ran a video report on its website. In it, the NYT reporter Adam B. Ellick interviewed some Pakistani pop stars to gauge how lifestyle liberals were being affected by the spectre of so-called ‘Talibanisation’ in Pakistan. To his surprise, almost every single pop artiste that he managed to engage, refused to believe that there were men willing to blow themselves up in public in the name of faith.

It wasn’t an outright denial, as such, but the interviewed pop acts went to great lengths to ‘prove’ that the attacks were being carried out at the behest of the US, and that those who were being called ‘terrorists’ were simply fighting for their rights. Ellick’s surprise was understandable. Between 2007 and 2009, hundreds of people had already been killed in Pakistan by suicide bombers.

But it wasn’t just these ‘confused’ lifestyle liberals who chose to look elsewhere for answers when the answer was right in front of them. Unregulated talk shows on TV news channels were constantly providing space to men who would spin the most ludicrous narratives that presented the terrorists as ‘misunderstood brothers.’

From 2007 till 2014, terrorist attacks and assassinations were a daily occurrence. Security personnel, politicians, men, women and children were slaughtered. Within hours, the cacophony of inarticulate noises on the electronic media would drown out these tragedies. The bottom-line of almost every such ‘debate’ was always, ‘ye hum mein se nahin’ [these (terrorists) are not from among us]. In fact, there was also a song released with this as its title and ‘message.’

The perpetrators of the attacks were turned into intangible, invisible entities, like characters of urban myths that belong to a different realm. The fact was that they were very much among us, for all to see, even though most Pakistanis chose not to.

Just before the 2013 elections, the website of an English daily ran a poll on the foremost problems facing Pakistan. The poll mentioned unemployment, corruption, inflation and street crimes, but there was no mention of terrorism even though, by 2013, thousands had been killed in terrorist attacks.

So how does one explain this curious refusal to acknowledge a terrifying reality that was operating in plain sight? In an August 3, 2018 essay for The Guardian, Keith Kahn-Harris writes that individual self-deception becomes a problem when it turns into ‘public dogma.’ It then becomes what is called ‘denialism.’

The American science journalist and author Michael Specter, in his book Denialism, explains it to mean an entire segment of society, when struggling with trauma, turning away from reality in favour of a more comfortable lie. Psychologists have often explained denial as a coping mechanism that humans use in times of stress. But they also warn that if denial establishes itself as a constant disposition in an individual or society, it starts to inhibit the ability to resolve the source of the stress.

Denialism, as a social condition, is understood by sociologists as an undeclared ‘ism’, adhered to by certain segments of a society whose rhetoric and actions in this context can impact a country’s political, social and even economic fortunes.

In the January 2009 issue of European Journal of Public Health, Pascal Diethelm and Martin McKee write that the denialism process employs five main characteristics. Even though Diethelm and McKee were more focused on the emergence of denialism in the face of evidence in scientific fields of research, I will paraphrase four out of the five stated characteristics to explore denialism in the context of extremist violence in Pakistan from 2007 till 2017.

The deniers have their own interpretation of the same evidence. In early 2013, when a study showed that 1,652 people had been killed in 2012 alone in Pakistan because of terrorism, an ‘analyst’ on a news channel falsely claimed that these figures included those killed during street crimes and ‘revenge murders.’ Another gentleman insisted that the figures were concocted by foreign-funded NGOs ‘to give Pakistan and Islam a bad name.’

This brings us to denialism’s second characteristic: The use of fake experts. These are individuals who purport to be experts in a particular area but whose views are entirely inconsistent with established knowledge. During the peak years of terrorist activity in the country, self-appointed ‘political experts’ and ‘religious scholars’ were a common sight on TV channels. Their ‘expert opinions’ were heavily tilted towards presenting the terrorists as either ‘misunderstood brothers’ or people fighting to impose a truly Islamic system in Pakistan. Many such experts suddenly vanished from TV screens after the intensification of the military operation against militants in 2015. Some were even booked for hate speech.

The third characteristic is about selectivity, drawing on isolated opinions or highlighting flaws in the weakest opinions to discredit entire facts. In October 2012, when extremists attempted to assassinate a teenaged school girl, Malala Yousafzai, a sympathiser of the extremists on TV justified the assassination attempt by mentioning ‘similar incidents’ that he discovered in some obscure books of religious traditions. Within months Malala became the villain, even among some of the most ‘educated’ Pakistanis. When the nuclear physicist and intellectual Dr Pervez Hoodbhoy exhibited his disgust over this, he was not only accused of being ‘anti-Islam’, but his credibility as a scientist too was questioned.

The fourth characteristic is about misrepresenting the opposing argument to make it easier to refute. For example, when terrorists were wreaking havoc in Pakistan, the arguments of those seeking to investigate the issue beyond conspiracy theories and unabashed apologias, were deliberately misconstrued as being criticisms of religious faith.

Today we are seeing all this returning. But this time, ‘experts’ are appearing on TV pointing out conspiracies and twisting facts about the Covid-19 pandemic and vaccines. They are also offering their expert opinions on events such as the Aurat March and, in the process, whipping up a dangerous moral panic.

It seems, not much was learned by society’s collective disposition during the peak years of terrorism and how it delayed a timely response that might have saved hundreds of innocent lives.

Wednesday, 17 March 2021

Jaishankar’s problem is stark – no amount of external PR can cover up India’s truth

S Jaishankar has an unenviable task. He has been handed over the job to give a liberal gloss to a government that cannot spell l-i-b-e-r-a-l. More than manage external relations, he is here to manage external public relations, to ensure that the Narendra Modi government doesn’t get a bad international image. Now, that’s manifold more challenging than managing domestic media, mostly darbari if not outright sarkari, with a handful of carrots and sticks. So, you shouldn’t blame the hon’ble Minister of External Affairs if he occasionally botches it up.

As he did last Saturday at the India Today conclave. He was asked about India’s downgrading by two of the leading democracy rating agencies. The US-based non-government organisation Freedom House released a report that classified India as “partly free”, down from “free” earlier. Sweden-based Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute has categorised India as an “electoral autocracy”. Jaishankar was aggressive in his response: “It is hypocrisy. We have a set of self-appointed custodians of the world who find it very difficult to stomach that somebody in India is not looking for their approval, is not willing to play the game they want to play. So they invent their rules, their parameters, pass their judgements and make it look as if it is some kind of global exercise.”

Now, Jaishankar is an educated man. He must know some basic logical fallacies that any intelligent argument must avoid. Usually, at the top of that list is ad hominem, Latin for “against the man”. This happens when someone replaces logical argumentation with criticism based on personal characteristics, background or other features irrelevant to the argument at issue. One variety of ad hominem is called “tu quoque”, Latin for “you too”. It distracts from the argument by pointing out hypocrisy in the opponent. This is a logical fallacy and does not prove anything simply because even hypocrites can tell the truth. When an otherwise intelligent and educated person uses this type of argumentation, you know he is really short on logic and facts.

This is not to dispute Jaishankar’s charge of hypocrisy. Of course, Europe or North America is nobody to distribute certificates of democracy. Not just because their certificates are inevitably linked to their foreign policy and economic interests but also because their own democracy is deeply flawed. The list of autocracies that the US has spawned and supported is too long to be enumerated. Besides, Freedom House and V-Dem are no gold standards of democracy rating. Actually, there is no gold standard in this field. Any quantitative measurement or categorisation of democracy is inevitably a subjective exercise open to challenge. All rating agencies invite experts who inevitably bring their own values. There is no way to have a completely objective rating of democracy. But subjective is not arbitrary and values are not necessarily biases. If long literary essays can be evaluated in terms of quantitative marks in an examination, the same holds true for democracy.

India craves world rankings

S. Jaishankar would know that the Freedom House and V-Dem have not invented democracy ratings or categorisations to damn his government. They have been publishing annual democracy ratings for most countries of the world for a fairly long time. He would also know that besides these two, there are other ratings such as Democracy Index by The Economist. There is also Press Freedom Index. Besides, there are reports by Amnesty International and UN Rapporteur on Human Rights. He would surely know that of late India has consistently fallen in each and every rating of democracy and has been severely indicted in human rights reports. These reports happen to have given a number and a name to what anyone who knows anything about India knows so well.

No doubt, each of these ratings is from a Western liberal understanding of what a democracy is. Yet it would stretch one’s credulity too far to suggest that all of them are into a grand conspiracy against India. It was rich of Jaishankar to claim that India was not looking for approval from the West. Facts suggest otherwise. No prime minister before Narendra Modi has held melas outside India to promote his image. No head of government was as keen to please an American president as Modi was to Donald Trump. No government has made such a song and dance about a routine Ease of Doing Business Index as this one did, a ranking that landed in a manipulation controversy. Never have Indian government officials preferred International Monetary Fund (IMF) data over India’s own statistics as during this government. No one in the world has tried to claim credit for a high score on severity of lockdown index as this government’s enthusiasts did. Ever since gaining Independence from colonial rule, no Indian government has been as craven in its need for Western certificates as this one is.

Facts, not verbiage

The only honest and intelligent way of questioning such ratings would be to counter them with facts. Jaishankar had only one fact to offer: that in India, everyone including the defeated parties accepts election results. But he forgot that the main target of this much-needed punch was Trump who was recommended to the American electorate by Modi himself. Besides, this fact only proves the fairness of counting and, at best, electoral process. It does not disprove widespread anxiety about the worsening state of civil liberties, capture of democratic institutions, erosion in the freedom of media, judiciary and other watchdogs, attack on political opponents and criminalisation of dissent in today’s India. In fact, the whole point of calling India an “electoral autocracy” is this: elections happen more or less fairly, but the country is non-democratic in between two elections. Unwittingly, Jaishankar has conceded this point.

The only other option would be to come up with an alternative way of measuring democracy. A news report says that the Ministry of External Affairs might support an independent Indian think tank to do an alternative global rating of democracies. At any other time, this should have been welcomed as an instance of the kind of intellectual ambition non-Western democracies must show. In today’s context, it is more likely to be another version of Colonel Gaddafi’s Green Book that sought to challenge the hegemony of Western political philosophy through some verbiage.

Mr Jaishankar’s attempt to clothe up the current state of Indian democracy is stark: The Emperor is naked. And no amount of words can dress it up.

Saturday, 6 February 2021

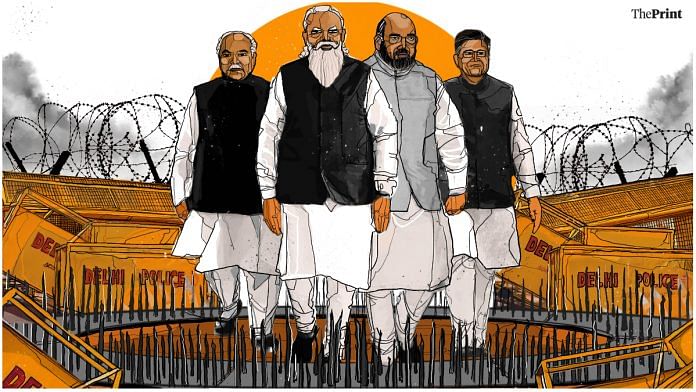

Modi govt has lost farm laws battle, now raising Sikh separatist bogey will be a grave error

Protests over the three farm reform laws are well into the third month now. There are six key facts, or facts as we see them, that we can list here:

1. The farm laws, by and large, are good for the farmers and India. At various points of time, most major political parties and leaders have wanted these changes. However, many of you might still disagree. But then, this is an opinion piece. I explained it in detail in this, Episode 571 of #CutTheClutter.

2. Whether the laws are good or bad for the farmer no longer matters. In a democracy, all that matters is what people affected by a policy change believe — in this case, the farmers of the northern states. Facts don’t matter if you’ve failed to convince them.

3. The Modi government is right when it says this is no longer about the farm laws. Because nobody is talking about MSP, subsidies, mandis and so on. Then what’s it about?

4. The short answer is, it is about politics. And why not? There is no democracy without politics. When the UPA was in power, the BJP opposed all its good ideas, from the India-US nuclear deal to FDI in insurance and pension. Now it’s implementing the same policies at the rate of, say, 6X.

5. As far as the farm laws are concerned, the Modi government has already lost the battle. Again, you can disagree. But this is my opinion. And I will make my case.

6. Finally, the Modi government has two choices. It can let it fester, expand into a larger political war. Or it can cut its losses and, as the Americans say, get off the kerb.

Here is the evidence that lets us say that the Modi government has lost the battle for these farm laws.

You see even a Modi-Shah BJP is unlikely to risk reopening this front at that point. In fact, the bellwether heartland state elections, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan, will be exactly 12 months away. Two of them have strong Congress incumbents and in the third, the BJP has bought and stolen power. Nobody’s risking losing these to make their point over farm reforms. These laws, then, are as bad as dead in the water.

Again, unilaterally, the government has already made a commitment of continuing with Minimum Support Price (MSP), although there is nothing in the laws saying it will be taken away. With so much already given away, the battle over the farm laws is lost.

The Modi government’s challenge now is to buy normalcy without making it look like a defeat. We know that it got away with one such, with the new land acquisition law. But that issue was still confined to Parliament. This is on the streets, highway choke-points, and in the expanse of wheat and paddy all around Delhi. This can spread. If the government retreats in surrender, this issue may close, but politics will rage. And why not? What is democracy but competitive politics, brutal, fair and fun? The next targets will then be other reform measures, from the new labour laws to the public listing of LIC.

What are the errors, or blunders, that brought India’s most powerful government in 35 years here? I shall list five:

1. Bringing in these laws through the ordinance route was a blunder. I speak from 20/20 hindsight, but then I am a commentator, not a political leader. To usher in the promise of sweeping change affecting the lives of more than half a billion people, the correct way would have been to market the ideas first. We don’t know if Narendra Modi now regrets not having prepared the ground for it. But the fact is, people at the mass level would be suspicious of such change through ordinances. Especially if you aren’t talking to them.

2. The manner in which the laws were pushed through Rajya Sabha added to these suspicions. This needed better parliamentary craft than the blunt use of vocal chords. This helped fan the fire, or spread the ‘hawa’ that something terrible was being forced down the surplus-producing farmers’ throats.

3. The party was riding far too high on its majority to care about allies and friends. If it had taken them along respectfully, the passage through Rajya Sabha wouldn’t have been so ungainly. At least the Akalis should never have been lost. But, as we’ve said before, this BJP does not understand Punjab or the Sikhs.

4. It also underestimated the frustration among the Jats of Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh, disempowered by the Modi-Shah politics. The senior-most Jat leaders in the Modi council of ministers are both inconsequential ministers of state. One is from distant Barmer in Rajasthan. The most visible of them, Sanjeev Balyan, won from Muzaffarnagar, where the big pro-Tikait mahapanchayat was held. In Haryana, the BJP has no Jat who counts. On the contrary, it found the marginalisation of Jat power as its big achievement. It refused to learn even from statewide, violent Jat agitations for reservations. The anger then was rooted in political marginalisation, as it is now. Ask why the BJP’s Jat ally Dushyant Chautala, or any of its Jat MPs/MLAs in UP, especially Balyan, are not on the ground, marketing these reforms? They wouldn’t dare.

5. The BJP conceded too much, too soon, unilaterally in the negotiations. It doesn’t have much more to give now. And the farm leaders have conceded nothing.

In conclusion, where does the Modi government go from here? One approach could be to tire the farmers out. On all evidence, that is not about to happen. Rabi harvest in April is still nearly 75 days away, and with much work done by mechanical harvesters and migrant workers, families would be quite capable of keeping the pickets full.

The next expectation would be that the Jats would ultimately make a deal. This is plausible. Note the key difference between Singhu and Ghazipur. In the first, no politician can even go for a selfie. Ask Ravneet Singh Bittu of the Congress, who was turned out unceremoniously. But everybody can go to Ghazipur and be photographed hugging Tikait. The Congress, Left, RLD, RJD, AAP, all of them. Even Sukhbir Singh Badal comes to Ghazipur, instead of Singhu to meet his fellow Sikhs from Punjab. Wherever there is politics and politicians, conflict resolution is possible. But what happens if this becomes a reality?

This will leave India and the Modi government with the most dangerous outcome of all. It will corner the Sikhs of Punjab. Already, the lousy barricading visuals and government’s prickly response to something as trivial as some celebrity tweets is threatening to redefine the issue from farm laws to national unity. The Modi government will err gravely if it changes the headline from farm protests to Sikh separatism.

This crisis requires political sophistication and governance skills. This BJP has neither. It has, instead, political skills and governance by clout, riding an all-conquering election-winning machine. It is the party’s inability to accept the realities of Indian politics and appreciate the limitations of a parliamentary majority that brought it here.

Does it have the smarts and sagacity to negotiate its way out of it? We can’t say. But we hope it does. Because the last thing India needs is to start another war for national unity. You would be nuts to reopen an issue in Punjab we all closed and buried by 1993.