Brian Merchant in The Guardian

The sprawling factory compound, all grey dormitories and weather-beaten warehouses, blends seamlessly into the outskirts of the Shenzhen megalopolis. Foxconn’s enormous Longhua plant is a major manufacturer of Apple products. It might be the best-known factory in the world; it might also might be among the most secretive and sealed-off. Security guards man each of the entry points. Employees can’t get in without swiping an ID card; drivers entering with delivery trucks are subject to fingerprint scans. A Reuters journalist was once dragged out of a car and beaten for taking photos from outside the factory walls. The warning signs outside – “This factory area is legally established with state approval. Unauthorised trespassing is prohibited. Offenders will be sent to police for prosecution!” – are more aggressive than those outside many Chinese military compounds.

But it turns out that there’s a secret way into the heart of the infamous operation: use the bathroom. I couldn’t believe it. Thanks to a simple twist of fate and some clever perseverance by my fixer, I’d found myself deep inside so-called Foxconn City.

It’s printed on the back of every iPhone: “Designed by Apple in California Assembled in China”. US law dictates that products manufactured in China must be labelled as such and Apple’s inclusion of the phrase renders the statement uniquely illustrative of one of the planet’s starkest economic divides – the cutting edge is conceived and designed in Silicon Valley, but it is assembled by hand in China.

The vast majority of plants that produce the iPhone’s component parts and carry out the device’s final assembly are based here, in the People’s Republic, where low labour costs and a massive, highly skilled workforce have made the nation the ideal place to manufacture iPhones (and just about every other gadget). The country’s vast, unprecedented production capabilities – the US Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated that as of 2009 there were 99 million factory workers in China – have helped the nation become the world’s second largest economy. And since the first iPhone shipped, the company doing the lion’s share of the manufacturing is the Taiwanese Hon Hai Precision Industry Co, Ltd, better known by its trade name, Foxconn.

Foxconn is the single largest employer in mainland China; there are 1.3 million people on its payroll. Worldwide, among corporations, only Walmart and McDonald’s employ more. As many people work for Foxconn as live in Estonia.

An employee directs jobseekers to queue up at the Foxconn recruitment centre in Shenzhen. Photograph: David Johnson/Reuters

Today, the iPhone is made at a number of different factories around China, but for years, as it became the bestselling product in the world, it was largely assembled at Foxconn’s 1.4 square-mile flagship plant, just outside Shenzhen. The sprawling factory was once home to an estimated 450,000 workers. Today, that number is believed to be smaller, but it remains one of the biggest such operations in the world. If you know of Foxconn, there’s a good chance it’s because you’ve heard of the suicides. In 2010, Longhua assembly-line workers began killing themselves. Worker after worker threw themselves off the towering dorm buildings, sometimes in broad daylight, in tragic displays of desperation – and in protest at the work conditions inside. There were 18 reported suicide attempts that year alone and 14 confirmed deaths. Twenty more workers were talked down by Foxconn officials.

The epidemic caused a media sensation – suicides and sweatshop conditions in the House of iPhone. Suicide notes and survivors told of immense stress, long workdays and harsh managers who were prone to humiliate workers for mistakes, of unfair fines and unkept promises of benefits.

The corporate response spurred further unease: Foxconn CEO, Terry Gou, had large nets installed outside many of the buildings to catch falling bodies. The company hired counsellors and workers were made to sign pledges stating they would not attempt to kill themselves.

Steve Jobs, for his part, declared: “We’re all over that” when asked about the spate of deaths and he pointed out that the rate of suicides at Foxconn was within the national average. Critics pounced on the comment as callous, though he wasn’t technically wrong. Foxconn Longhua was so massive that it could be its own nation-state, and the suicide rate was comparable to its host country’s. The difference is that Foxconn City is a nation-state governed entirely by a corporation and one that happened to be producing one of the most profitable products on the planet.

If the boss finds any problems, they don’t scold you then. They scold you later, in front of everyone, at a meeting

A cab driver lets us out in front of the factory; boxy blue letters spell out Foxconn next to the entrance. The security guards eye us, half bored, half suspicious. My fixer, a journalist from Shanghai whom I’ll call Wang Yang, and I decide to walk the premises first and talk to workers, to see if there might be a way to get inside.

The first people we stop turn out to be a pair of former Foxconn workers.

“It’s not a good place for human beings,” says one of the young men, who goes by the name Xu. He’d worked in Longhua for about a year, until a couple of months ago, and he says the conditions inside are as bad as ever. “There is no improvement since the media coverage,” Xu says. The work is very high pressure and he and his colleagues regularly logged 12-hour shifts. Management is both aggressive and duplicitous, publicly scolding workers for being too slow and making them promises they don’t keep, he says. His friend, who worked at the factory for two years and chooses to stay anonymous, says he was promised double pay for overtime hours but got only regular pay. They paint a bleak picture of a high-pressure working environment where exploitation is routine and where depression and suicide have become normalised.

“It wouldn’t be Foxconn without people dying,” Xu says. “Every year people kill themselves. They take it as a normal thing.”

Over several visits to different iPhone assembly factories in Shenzhen and Shanghai, we interviewed dozens of workers like these. Let’s be honest: to get a truly representative sample of life at an iPhone factory would require a massive canvassing effort and the systematic and clandestine interviewing of thousands of employees. So take this for what it is: efforts to talk to often skittish, often wary and often bored workers who were coming out of the factory gates, taking a lunch break or congregating after their shifts.

A Foxconn employee in a dormitory at Longhua. The rooms are currently said to sleep eight. Photograph: Wang Yishu / Imaginechina/Camera Press

The vision of life inside an iPhone factory that emerged was varied. Some found the work tolerable; others were scathing in their criticisms; some had experienced the despair Foxconn was known for; still others had taken a job just to try to find a girlfriend. Most knew of the reports of poor conditions before joining, but they either needed the work or it didn’t bother them. Almost everywhere, people said the workforce was young and turnover was high. “Most employees last only a year,” was a common refrain. Perhaps that’s because the pace of work is widely agreed to be relentless, and the management culture is often described as cruel.

Since the iPhone is such a compact, complex machine, putting one together correctly requires sprawling assembly lines of hundreds of people who build, inspect, test and package each device. One worker said 1,700 iPhones passed through her hands every day; she was in charge of wiping a special polish on the display. That works out at about three screens a minute for 12 hours a day.

More meticulous work, like fastening chip boards and assembling back covers, was slower; these workers have a minute apiece for each iPhone. That’s still 600 to 700 iPhones a day. Failing to meet a quota or making a mistake can draw public condemnation from superiors. Workers are often expected to stay silent and may draw rebukes from their bosses for asking to use the restroom.

Xu and his friend were both walk-on recruits, though not necessarily willing ones. “They call Foxconn a fox trap,” he says. “Because it tricks a lot of people.” He says Foxconn promised them free housing but then forced them to pay exorbitantly high bills for electricity and water. The current dorms sleep eight to a room and he says they used to be 12 to a room. But Foxconn would shirk social insurance and be late or fail to pay bonuses. And many workers sign contracts that subtract a hefty penalty from their pay if they quit before a three-month introductory period.

The body-catching nets are still there. They look a bit like tarps that have blown off the things they’re meant to cover

On top of that, the work is gruelling. “You have to have mental management,” says Xu, otherwise you can get scolded by bosses in front of your peers. Instead of discussing performance privately or face to face on the line, managers would stockpile complaints until later. “When the boss comes down to inspect the work,” Xu’s friend says, “if they find any problems, they won’t scold you then. They will scold you in front of everyone in a meeting later.”

“It’s insulting and humiliating to people all the time,” his friend says. “Punish someone to make an example for everyone else. It’s systematic,” he adds. In certain cases, if a manager decides that a worker has made an especially costly mistake, the worker has to prepare a formal apology. “They must read a promise letter aloud – ‘I won’t make this mistake again’– to everyone.”

This culture of high-stress work, anxiety and humiliation contributes to widespread depression. Xu says there was another suicide a few months ago. He saw it himself. The man was a student who worked on the iPhone assembly line. “Somebody I knew, somebody I saw around the cafeteria,” he says. After being publicly scolded by a manager, he got into a quarrel. Company officials called the police, though the worker hadn’t been violent, just angry.

“He took it very personally,” Xu says, “and he couldn’t get through it.” Three days later, he jumped out of a ninth-storey window.

So why didn’t the incident get any media coverage? I ask. Xu and his friend look at each other and shrug. “Here someone dies, one day later the whole thing doesn’t exist,” his friend says. “You forget about it.”

Employees have lunch in a vast refectory at the Foxconn Longhua plant. Photograph: Wang Yishu/Imaginechina/Camera Press

‘We look at everything at these companies,” Steve Jobs said after news of the suicides broke. “Foxconn is not a sweatshop. It’s a factory – but my gosh, they have restaurants and movie theatres… but it’s a factory. But they’ve had some suicides and attempted suicides – and they have 400,000 people there. The rate is under what the US rate is, but it’s still troubling.” Apple CEO, Tim Cook, visited Longhua in 2011 and reportedly met suicide-prevention experts and top management to discuss the epidemic.

In 2012, 150 workers gathered on a rooftop and threatened to jump. They were promised improvements and talked down by management; they had, essentially, wielded the threat of killing themselves as a bargaining tool. In 2016, a smaller group did it again. Just a month before we spoke, Xu says, seven or eight workers gathered on a rooftop and threatened to jump unless they were paid the wages they were due, which had apparently been withheld. Eventually, Xu says, Foxconn agreed to pay the wages and the workers were talked down.

When I ask Xu about Apple and the iPhone, his response is swift: “We don’t blame Apple. We blame Foxconn.” When I ask the men if they would consider working at Foxconn again if the conditions improved, the response is equally blunt. “You can’t change anything,” Xu says. “It will never change.”

Wang and I set off for the main worker entrance. We wind around the perimeter, which stretches on and on – we have no idea this is barely a fraction of the factory at this point.

After walking along the perimeter for 20 minutes or so, we come to another entrance, another security checkpoint. That’s when it hits me. I have to use the bathroom. Desperately. And that gives me an idea.

There’s a bathroom in there, just a few hundred feet down a stairwell by the security point. I see the universal stick-man signage and I gesture to it. This checkpoint is much smaller, much more informal. There’s only one guard, a young man who looks bored. Wang asks something a little pleadingly in Chinese. The guard slowly shakes his head no, looks at me. The strain on my face is very, very real. She asks again – he falters for a second, then another no.

We’ll be right back, she insists, and now we’re clearly making him uncomfortable. Mostly me. He doesn’t want to deal with this. Come right back, he says. Of course, we don’t.

To my knowledge, no American journalist has been inside a Foxconn plant without permission and a tour guide, without a carefully curated visit to selected parts of the factory to demonstrate how OK things really are.

Maybe the most striking thing, beyond its size – it would take us nearly an hour to briskly walk across Longhua – is how radically different one end is from the other. It’s like a gentrified city in that regard. On the outskirts, let’s call them, there are spilt chemicals, rusting facilities and poorly overseen industrial labour. The closer you get to the city centre – remember, this is a factory – the more the quality of life, or at least the amenities and the infrastructure, improves.

‘Not a good place for human beings’: Foxconn Longhua. Photograph: Brian Merchant

As we get deeper in, surrounded by more and more people, it feels like we’re getting noticed less. The barrage of stares mutates into disinterested glances. My working theory: the plant is so vast, security so tight, that if we are inside just walking around, we must have been allowed to do so. That or nobody really gives a shit. We start trying to make our way to the G2 factory block, where we’ve been told iPhones are made. After leaving “downtown”, we begin seeing towering, monolithic factory blocks – C16, E7 and so on, many surrounded by crowds of workers.

I worry about getting too cavalier and remind myself not to push it; we’ve been inside Foxconn for almost an hour now. The crowds have been thinning out the farther away from the centre we get. Then there it is: G2. It’s identical to the factory blocks that cluster around it, that threaten to fade into the background of the smoggy static sky.

G2 looks deserted, though. A row of impossibly rusted lockers runs outside the building. No one’s around. The door is open, so we go in. To the left, there’s an entry to a massive, darkened space; we’re heading for that when someone calls out. A floor manager has just come down the stairs and he asks us what we’re doing. My translator stammers something about a meeting and the man looks confused; then he shows us the computer monitoring system he uses to oversee production on the floor. There’s no shift right now, he says, but this is how they watch.

No sign of iPhones, though. We keep walking. Outside G3, teetering stacks of black gadgets wrapped in plastic sit in front of what looks like another loading zone. A couple of workers on smartphones drift by us. We get close enough to see the gadgets through the plastic and, nope, not iPhones either. They look like Apple TVs, minus the company logo. There are probably thousands stacked here, awaiting the next step in the assembly line.

If this is indeed where iPhones and Apple TVs are made, it’s a fairly aggressively shitty place to spend long days, unless you have a penchant for damp concrete and rust. The blocks keep coming, so we keep walking. Longhua starts to feel like the dull middle of a dystopian novel, where the dread sustains but the plot doesn’t.

We could keep going, but to our left, we see what look like large housing complexes, probably the dormitories, complete with cagelike fences built out over the roof and the windows, and so we head in that direction. The closer we get to the dorms, the thicker the crowds get and the more lanyards and black glasses and faded jeans and sneakers we see. College-age kids are gathered, smoking cigarettes, crowded around picnic tables, sitting on kerbs.

And, yes, the body-catching nets are still there. Limp and sagging, they give the impression of tarps that have half blown off the things they’re supposed to cover. I think of Xu, who said: “The nets are pointless. If somebody wants to commit suicide, they will do it.”

We are drawing stares again – away from the factories, maybe folks have more time and reason to indulge their curiosity. In any case, we’ve been inside Foxconn for an hour. I have no idea if the guard put out an alert when we didn’t come back from the bathroom or if anyone is looking for us or what. The sense that it’s probably best not to push it prevails, even though we haven’t made it on to a working assembly line.

A protester dressed as a factory worker outside an Apple retail outlet in Hong Kong, May 2011. Photograph: Antony Dickson/AFP/Getty Images

We head back the way we came. Before long, we find an exit. It’s pushing evening as we join a river of thousands and, heads down, shuffle through the security checkpoint. Nobody says a word. Getting out of the haunting megafactory is a relief, but the mood sticks. No, there were no child labourers with bleeding hands pleading at the windows. There were a number of things that would surely violate the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration code – unprotected construction workers, open chemical spillage, decaying, rusted structures, and so on – but there are probably a lot of things at US factories that would violate OSHA code too. Apple may well be right when it argues that these facilities are nicer than others out there. Foxconn was not our stereotypical conception of a sweatshop. But there was a different kind of ugliness. For whatever reason – the rules imposing silence on the factory floors, its pervasive reputation for tragedy or the general feeling of unpleasantness the environment itself imparts – Longhua felt heavy, even oppressively subdued.

When I look back at the photos I snapped, I can’t find one that has someone smiling in it. It does not seem like a surprise that people subjected to long hours, repetitive work and harsh management might develop psychological issues. That unease is palpable – it’s worked into the environment itself. As Xu said: “It’s not a good place for human beings.”

Amelia Hill in The Guardian

We are entering the age of no retirement. The journey into that chilling reality is not a long one: the first generation who will experience it are now in their 40s and 50s. They grew up assuming they could expect the kind of retirement their parents enjoyed – stopping work in their mid-60s on a generous income, with time and good health enough to fulfil long-held dreams. For them, it may already be too late to make the changes necessary to retire at all.

In 2010, British women got their state pension at 60 and men got theirs at 65. By October 2020, both sexes will have to wait until they are 66. By 2028, the age will rise again, to 67. And the creep will continue. By the early 2060s, people will still be working in their 70s, but according to research, we will all need to keep working into our 80s if we want to enjoy the same standard of retirement as our parents.

This is what a world without retirement looks like. Workers will be unable to down tools, even when they can barely hold them with hands gnarled by age-related arthritis. The raising of the state retirement age will create a new social inequality. Those living in areas in which the average life expectancy is lower than the state retirement age (south-east England has the highest average life expectancy, Scotland the lowest) will subsidise those better off by dying before they can claim the pension they have contributed to throughout their lives. In other words, wealthier people become beneficiaries of what remains of the welfare state.

Retirement is likely to be sustained in recognisable form in the short and medium term. Looming on the horizon, however, is a complete dismantling of this safety net.

For those of pensionable age who cannot afford to retire, but cannot continue working – because of poor health, or ageing parents who need care, or because potential employers would rather hire younger workers – the great progress Britain has made in tackling poverty among the elderly over the last two decades will be reversed. This group is liable to suffer the sort of widespread poverty not seen in Britain for 30 to 40 years.

Many now in their 20s will be unable to save throughout their youth and middle age because of increasingly casualised employment, student debt and rising property prices. By the time they are old, members of this new generation of poor pensioners are liable to be, on average, far worse off than the average poor pensioner today.

A series of factors has contributed to this situation: increased life expectancy, woeful pension planning by successive governments, the end of the final-salary pension scheme (in which people got two-thirds of their final salary as a pension) and our own failure to save.

For two months, as part of an experiment by the Guardian in collaborative reporting, I have been investigating what retirement looks like today – and what it might look like for the next wave of retirees, their children and grandchildren. The evidence reveals a sinkhole beneath the state’s provision of pensions. Under the weight of our vastly increased longevity, retirement – one of our most cherished institutions – is in danger of collapsing into it.

Working just as hard, but unpaid? What happens when women retire

Many of those contemplating retirement are alarmed by the new landscape. A 62-year-old woman, who is for the first time in her life struggling to pay her mortgage (and wishes to remain anonymous), told me: “I am more stressed now than I was in my 30s. I lived on a very tight budget then, but I was young and could cope emotionally. I don’t mean to sound bitter, but I never thought I would feel this scared of the future at my age. I’m not remotely materialistic and have never wanted a fancy lifestyle. But not knowing if I will be without a home in the next few months is a very scary place to be.”

And it is not just the older generation who fear old age. Adam Palfrey is 30, with three children and a disabled wife who cannot work. “I must confess, I am absolutely terrified of retirement,” he told me. “I have nothing stashed away. Savings are out of the question. I only just earn enough that, with housing benefit, disability living allowance and tax credits, I manage to keep our heads above water. I work every hour I can just to keep things afloat. There’s no way I could keep this up aged 70-plus, just so that my partner and I can live a basic life. As for my three children … God knows. I can scarcely bring myself to think about it.”

It is not news that the population is ageing. What is remarkable is that we have failed to prepare the ground for this inevitable change. Life expectancy in Britain is growing by a dramatic five hours a day. Thanks to a period of relative peace in the UK, low infant mortality and continual medical advances, over the past two decades the life expectancy of babies born here has increased by some five years. (A baby born at the end of my eight-week The new retirement series has a life expectancy almost 12 days longer than a baby born at the start of it.)

Dr Peter Jarvis and Sue Perkins at Bletchley Park. Photograph: Linda Nylind for the Guardian

In 2014, the average age of the UK population exceeded 40 for the first time – up from 33.9 in 1974. In little more than a decade, half of the country’s population will be aged over 50. This will transform Britain – and it is no mere blip; the trend will continue as life expectancy increases. This year marked a demographic turning point in the UK. As the baby-boom generation (now aged between 53 and 71) entered retirement, for the first time since the early 1980s there were more people either too old or too young to work than there were of working age.

The number of people in the UK aged 85 or more is expected to more than double in the next 25 years. By 2040, nearly one in seven Britons will be over 75. Half of all children born in the UK are predicted to live to 103. Some 10 million of us currently alive in the UK (and 130 million throughout Europe) are likely to live past the age of 100.

Governments see raising the state retirement age as a way to cover the cost of an ageing population

The challenges are considerable. The tax imbalance that comes with an ageing population, whose tax contribution falls far short of their use of services, will rise to £15bn a year by 2060. Covering this gap will cost the equivalent of a 4p income tax rise for the working-age population.

It is easy to see why governments might regard raising the state retirement age as a way to cover the cost of an ageing population. A successful pursuit of full employment of people into their late 60s could maintain the ratio of workers to non-workers for many decades to come. And were the employment rate for older workers to match that of the 30-40 age group, the additional tax payments could be as much as £88.4bn. According to PwC’s Golden Age Index, had our employment rates for those aged 55 years and older been as high as those in Sweden between 2003 and 2013, UK national GDP would have been £105bn – or 5.8% – higher.

There are, of course, problems to this approach. Those who can happily work into their 70s and beyond are likely to be the privileged few: the highly educated elite who haven’t spent their working lives in jobs that negatively affect their health. If the state pension age is pushed further away, for those with failing health, family responsibilities or no jobs, life will become very difficult.

The new state pension, introduced on 6 April 2016, will be paid to men born on or after 6 April 1951, and women born on or after 6 April 1953. Assuming you have paid 35 years of National Insurance, it will pay out £155.65 a week. The old scheme (worth a basic sum of £119.30 per week, with more for those who paid into additional state pension schemes such as Serps or S2P) applies to those born before those dates.

Frank Field, Labour MP and chair of the work and pensions select committee, told me that the new figure of just over £8,000 a year is enough to guarantee all pensioners a decent standard of living: an “adequate minimum”, as he put it. Anything above that, he said, should be privately funded, without tax breaks or other government help.

“Once the minimum has been reached, it’s not the job of government to bribe people to save more,” he says. “To provide luxurious pension payments was never the aim of the state pension.”

Whether the new state pension can really be described as a “comfortable minimum” turns out to be a matter of opinion. Dr Ros Altmann, who was brought into government in April 2015 to work on pensions policy, is the UK government’s former older workers’ champion and a governor of the Pensions Policy Institute. When I relayed Field’s comments to her, she was left briefly speechless. Then she managed a “wow”. “Did he really say that? Would he be happy to live on just over £8,000 a year?” she asked, finally.

Tom McPhail, head of retirement policy at financial advisers Hargreaves Lansdown, is clear that the new state pension has not been set at a high-enough level to guarantee a dignified older age to those who have no other income. “How sufficient is the new state pension? That’s an easy one to answer: It’s not,” he said.

Field makes the assumption that people have enough additional private financial ballast to bolster their state pensions. But the reality is that many people have neither savings – nearly a third of all households would struggle to pay an unexpected £500 bill – nor sufficient private pension provision to bring their state pension entitlement up to a level to ensure a comfortable retirement by most people’s understanding of the term. In fact, savings are the great dividing line in retirement, and the scale of the so-called “pension gap” – the gap between what your pension pot will pay out and the amount you need to live comfortably in older age – is shocking.

Three in 10 Britons aged 55-64 do not have any pension savings at all. Almost half of those in their 30s and 40s are not saving adequately or at all. In part, that is because we underestimate the amount of money we need to save. According to research by Saga earlier this month, four in 10 of those aged over 40 have no idea of the cost of even a basic lifestyle in retirement. When it came to understanding the size of the total pension pot they would need to fund retirement, over 80% admitted they had no idea how big this would need to be.

Retirement is an ancient concept. It caused one of the worst military disasters ever faced by the Roman empire when, in AD14, the imperial power increased the retirement age and decreased the pensions of its legionaries, causing mutiny in Pannonia and Germany. The ringleaders were rounded up and disposed of, but the institution remains so highly prized that any threat to its continued existence is liable to cause mutiny. “Retirement has been stolen. You can pay in as much as you like. They will never pay back. Time for a grey revolution,” one reader emailed.

It was in 1881 that the German chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, made a radical speech to the Reichstag, calling for government-run financial support for those aged over 70 who were “disabled from work by age and invalidity”.

Roger Hall in Porlock Bay, Somerset. Photograph: Sam Frost for the Guardian

The scheme wasn’t the socialist ideal it is sometimes assumed to be: Bismarck was actually advocating a disability pension, not a retirement pension as we understand it today. Besides, the retirement age he recommended just about aligned with average life expectancy in Germany at that time. Bismarck did, however, have a further vision that was genuinely too radical for his era: he proposed a pension that could be drawn at any age, if the contributor was judged unfit for work. Those drawing it earlier would receive a lower amount.

This notion is surfacing again in various forms. The New Economics Foundation isarguing for a shorter working week, via a “slow retirement”, in which employees give up an hour of work per week every year from the age of 35. The idea is that older workers will release more of their work time to younger ones, which will allow a steady handover of retained wisdom. A universal basic income, whereby everyone receives a set sum from the state each year, regardless of how much they do or don’t work, might have a similar effect, enabling people to move to part-time work as they age.

Widespread poverty among the over-65s led to the 1946 National Insurance Act, which introduced the first contributory, flat-rate pension in the UK for women of 60 and men of 65. At first, pension rates were low and most pensioners did not have enough to get by. But by the late 1970s, the value of the state pension rose and an increasing number of people – mainly men – were able to benefit from occupational pension schemes. By 1967, more than 8 million employees working for private companies were entitled to a final-salary pension, along with 4 million state workers. In 1978, the Labour government introduced a fully fledged “earnings-linked” state top-up system for those without access to a company scheme.

With pension payments now at a rate that enabled older people to stop work without risking penury, older men (and to a lesser extent older women) began to enjoy a “third age”, which fell between the end of work and the start of old age. In 1970, the employment rate for men aged 60-64 was 81%; by 1985 it had fallen to 49.7%.

Access to a comfortable old age is a powerful political idea. John Macnicol, a visiting professor at the London School of Economics and author of Neoliberalising Old Age, believes that when jobs were needed for younger men after the second world war, a “socially elegant mythology” was created in which retirement was a time for older workers to kick back and relax.

He believes that in the 1990s, however, the narrative was cynically changed and the image of pensioners was deliberately altered: from being poor, frail, dependent and deserving, to well off, hedonistic, politically powerful and selfish. The notion of “the prosperous pensioner was constructed in the face of evidence that showed exactly the opposite to be the case”, he said, “so that the right to retirement [could be] undermined: more coercive working practices, forcing older people to stay in employment, could be presented as providing new ‘opportunities’, removing barriers to working, bestowing greater inclusion and even achieving upward social mobility”.

This change in attitude towards pensioners helped the government bring in a hike in retirement age. In 1995, the Conservative government under John Major announced a steady increase from 60 to 65 in the state pension age for women, to come in between April 2010 and April 2020. Most agreed that equalising the state pension age was fair enough. What they objected to is that the government waited until 2009 – a year before the increases were set to begin – to start contacting those affected, leaving thousands of women without time to rearrange their finances or adjust their employment plans to fill the gaping hole in their income.

Then, in 2011 – when the state pension age for women had risen to 63 – the coalition government accelerated the timetable: the state pension age for women will now reach 65 in November 2018, at which point it will rise alongside men’s: to 66 by 2020 and to 67 by 2028.

When she retired from the ministry of work and pensions in 2016, Ros Altmann stated that she was “not convinced the government had adequately addressed the hardship facing women who have had their state pension age increased at short notice”.

After surviving cancer at 52, Jackie Harrison, now 62, looked over her savings and decided she could just about afford to take early retirement. “I had achieved 36 years of national insurance contributions,” she said. “I used to phone the Department for Work and Pensions every year to ensure that I had worked enough to get my full pension at 60.”

Then she was told her personal pension age was increasing from 60 to 63 years and six months. “I wasn’t eligible for any benefits because of my partner’s pension, but I could nevertheless still just about manage until the new state retirement age,” she said. But when she was 58, the goalposts moved again – this time to 66. “I’d been out of the workplace for so long that I didn’t have a hope of being able to get back into it,” she said. “But nor did it give me enough time to make other financial arrangements.”

Harrison made the agonising decision to raise money by selling her family home and moving to a different city, where she could live more cheaply. Her decisions had heavy implications for the rest of her family – and the state. When she moved, she left behind a vulnerable adult daughter and baby grandchild and octogenarian parents.

“This is not the retirement I had planned at all,” Harrison told me. “I had loads of savings once, but now I live in a constant state of worry due to financial pressures. It seems so unfair when I have worked all my life and planned for my retirement. I just don’t know how I am going to manage for another four years”. Women born in the 1950s are already living in their age of no retirement.

In 2006, it became legal for employers to force their workers to retire at the age of 65. A campaign led by Age Concern and Help the Aged was swift and effective in its argument that the new default retirement age law broke EU rules and gave employers too much leeway to justify direct discrimination on the grounds of age. On 1 October 2011, the law was overturned.

Since then, Britain’s workforce has greyed almost before our eyes: in the last 15 years, the number of working people aged 50-64 has increased by 60% to 8 million (far greater than the increase in the population of people over 50). The proportion of people aged 70-74 in employment, meanwhile, has almost doubled in the past 10 years. This trend will continue. By 2020, one-third of the workforce will be over 50.

A worker at Steelite International ceramics in Stoke-on-Trent. Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian

The proportional increase may be substantial, but it charts growth from a low level. In empirical terms, the impact is less positive: almost one-third of people in the UK aged 50-64 are not working. In fact, a greater number are becoming jobless than finding employment: almost 40% of employment and support allowance claimants are over 50, an indication that many older people are unable to easily find new and sustainable work.

This is unsustainable: by 2020, an estimated 12.5m jobs will become vacant as a result of older people leaving the workforce. Yet there will only be 7 million younger people to fill them. If we can no longer rely on immigration to fill the gaps, employers will have to shed their prejudices, workplaces will have to be adapted, and social services will have to step in to provide the care that ageing people can no longer give their grandchildren, ageing spouses or parents if they remain in the workforce.

Forcing older people to work longer if they cannot easily do so can cause more harm than good

But forcing older people to work longer if they cannot easily do so can cause more harm than good. Prof Debora Price, director of the Manchester Institute for Collaborative Research on Ageing, told me: “There is evidence to suggest that opportunities for people to work beyond state pension age might well be making inequalities worse, since those able to work into later life tend to be men who are highly educated and have been in higher-paid jobs.”

One answer is to return to Bismarck’s original plan, whereby the state pension can be accessed early by anyone who chooses to collect a smaller pension sum at an age lower than the state retirement age, perhaps because of poor health or other commitments.

This option, however, was rejected last week by John Cridland, the former head of the Confederation of British Industry’s business lobby group, who was appointed by the government in March 2016 to help cut the UK’s £100bn a year pension costs by reviewing the state pension age.

Instead, Cridland has recommended that the state pension age should rise from 67 to 68 by 2039, seven years earlier than currently timetabled. This will push the state retirement age back for a year for anyone in their early 40s. Cridland has rejected calls for early access to the state pension for those in poor health, but has left the door open for additional means-tested support to be made available one year before state pension age for those unable to work owing to ill health or caring responsibilities.

In spite of their anxieties about money, one of the things I have been most struck by, in my many conversations with older readers, is the pleasure they take in life.

One grandmother told me: “Last week, I swept across a crowded pub to pick up a raffle prize … with my dress tucked into my knickers! A few years ago I would have been mortified. Not any more. Told ’em they were lucky it was cold and I had knickers on!”

Monica Hartwell, 69, is part of the team at the volunteer-run Regal theatre in Minehead, as well as the film society and the museum. “The joy of getting older is much greater self-confidence,” she told me. “It’s the loss of angst about what people think of you: the size of your bum or whether others are judging you correctly. It’s not an arrogance, but you know who you are when you’re older and all those roles you played to fit in when you were younger are irrelevant.”

Women in Ilkley, West Yorkshire, discuss retirement. Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian

The data bears out these experiences: 65 to 79 is the happiest age group for adults, according to the Office for National Statistics. Recently, a report claimed that women in their 80s have more enjoyable sex than those up to 30 years younger. Other research has found that 75% of those aged 50 and over are less bothered about what people think of them and 61% enjoy life more than when they were younger.

So what is the secret to a successful retirement? Private companies run courses to help those on the verge of retirement plan for changes in income, time and relationships. I have spoken to those running such courses, as well as those who have retired. The consensus is that there are five pillars, all of which rest on the “money bit” – the basic level of financial security without which later life is hard. Once that foundation is in place, retirees can build up the second pillar: a social network to replace their former work community. The third pillar is having purpose and challenging one’s mind. Fourth is ongoing personal development – exploring, questioning and learning are an important part of what makes us human; this should never stop, I was told. The fifth and final pillar is having fun.

I tried explaining final-salary pensions to a 20-year-old recently. They looked at me quizzically, as though I was telling them that I had seen a unicorn. When that same 20-year-old, however, tries to explain the traditional concept of retirement to their own children, they might well be met with the same level of incomprehension.

For their children, life might well be more like the joke that Ali Seamer emailed to me during a recent Q&A I ran with readers as part of my investigation into what retirement means today: “I’m going to have to work up to 6pm on the day of my funeral just to be able to afford the coffin,” he said.

In examining the reality of this new age of no retirement, I have become aware of two pitfalls undermining constructive debate. The first is the prejudice that an ageing population will place a huge burden on society.

This is refuted by numerous studies: the volunteer charity WRVS has done the most work to quantify the economic role played by older generations. Taking together the tax payments, spending power, caring and volunteer efforts of people aged 65-plus, it calculates that they contribute almost £40bn more to the UK economy than they receive in state pensions, welfare and health services.

The research suggests that this benefit to the economy will increase in coming years as increasing numbers of baby-boomers enter retirement. By 2030, it projects that the net contribution of older people will be worth some £75bn.

Older people’s contribution to society is not just economic. An ICM poll for the WRVS study found that 65% of older people say they regularly help out elderly neighbours; they are the most likely of all adult age groups to do so.

The second pitfall is the conflict between generations that can be caused by the issue of retirement. The financial problems of the young have been blamed on baby boomers. But the truth is that the UK pension languishes far below that which is provided in most developed countries. And this contributory, taxed income – pensioners pay tax just like anyone else – is all that many old people have to live on.

Nearly 2 million of those aged 55-64 do not have any private pension savings and despite the commonly held belief that older people are all mortgage-free, fewer than 48% of those aged 55-64 own their own homes outright and nearly a quarter are still renting. It is true that some have benefitted greatly from rises in house prices, but the cost of lending was high – often 10% or more – during the 1970s and 1980s. One in 10 of those aged 65 and over still have a mortgage.

For all the recent talk of the average pensioner household being £20 a week better off than working households, the truth is that many are actually working to supplement their income. Still, to people just entering the workforce, the lives of today’s pensioners look impossibly privileged.

Rachael Ingram sums it up. At 19, working full-time and studying for an Open University degree, she is already putting 10% of her income aside for her pension. “I shouldn’t be worrying about saving for my pension at my age,” she told me. “I’m saving money that could go towards a deposit for my first house – I’m currently renting a flat in Liverpool – or out socialising. But I have no faith in government or the state pension. There will be no one to look after me when I’m old.”

Aislinn Macklin-Doherty in The Guardian

Widespread concerns that the NHS will face the “toughest winter ever” are not exaggerated or unfounded – just look at the terrible news today from Worcestershire. We really should be worried for ourselves and our relatives. As a junior doctor and a researcher looking after cancer patients in the NHS, I am terrified by the prospect of what the next few months will bring. But we must not forget this is entirely preventable.

Three patients die at Worcestershire hospital amid NHS winter crisis

Our current crisis is down to the almost clockwork-like series of reshuffling, rebranding and top-down disorganisation of the services by government. It’s led to an inexorable decline in the quality of care.

I have also become aware of an insidious “takeover” by the private sector. It is both literal – in the provision of services – and ideological, with an overwhelming prevalence of business-speak being absorbed into our collective psyche. But the British public (and even many staff) remain largely unaware that this is happening.

Where the consultant physician or surgeon was once general, they now increasingly play second fiddle to chief executives and clinical business unit managers. Junior doctors such as myself (many of whom have spent 10-15 years practising medicine and have completed PhDs) must also fall in line to comply with business models and corporate strategy put forward by those with no clinical training or experience with patients.

It is this type of decision-making (based on little evidence) and seemingly unaccountable policymaking that means patient care is suffering. Blame cannot be laid at the feet of a population of demanding and ageing patients, nor the “health tourists” who are too often scapegoated.

The epitome of such changes is known as the “sustainability and transformation plans”. These will bring about some of the biggest shifts in how NHS frontline service are funded and run in recent history, and yet, worryingly, most of my own colleagues have not even heard of them. Even fewer feel able to influence them.

Sustainability and transformation plans will see almost a third of regions having an A&E closed or downgraded, and nearly half will see numbers of inpatient bed reductions. This is all part of the overarching five-year plan to drive through £22bn in efficiency savings in the NHS. But with overwhelming cuts in social services and community care and with GPs under immense pressure, people are forced to go to A&E because they quite simply do not have any other options.

I have been on the phone with patients with cancer who need to come into hospital with life-threatening conditions such as sepsis, and I have been forced to tell them, “We have no beds here you need to go to another local A&E.” Responses such as, “Please doctor don’t make me go there – last time there were people backed up down the corridors,” break my heart.

Ranjana Srivastava in The Guardian

Our consultation is nearly finished when my patient leans forward, and says, “So, doctor, in all this time, no one has explained this. Exactly how will I die?” He is in his 80s, with a head of snowy hair and a face lined with experience. He has declined a second round of chemotherapy and elected to have palliative care. Still, an academic at heart, he is curious about the human body and likes good explanations.

“What have you heard?” I ask. “Oh, the usual scary stories,” he responds lightly; but the anxiety on his face is unmistakable and I feel suddenly protective of him.

“Would you like to discuss this today?” I ask gently, wondering if he might want his wife there.

“As you can see I’m dying to know,” he says, pleased at his own joke.

If you are a cancer patient, or care for someone with the illness, this is something you might have thought about. “How do people die from cancer?” is one of the most common questions asked of Google. Yet, it’s surprisingly rare for patients to ask it of their oncologist. As someone who has lost many patients and taken part in numerous conversations about death and dying, I will do my best to explain this, but first a little context might help.

Some people are clearly afraid of what might be revealed if they ask the question. Others want to know but are dissuaded by their loved ones. “When you mention dying, you stop fighting,” one woman admonished her husband. The case of a young patient is seared in my mind. Days before her death, she pleaded with me to tell the truth because she was slowly becoming confused and her religious family had kept her in the dark. “I’m afraid you’re dying,” I began, as I held her hand. But just then, her husband marched in and having heard the exchange, was furious that I’d extinguish her hope at a critical time. As she apologised with her eyes, he shouted at me and sent me out of the room, then forcibly took her home.

It’s no wonder that there is reluctance on the part of patients and doctors to discuss prognosis but there is evidence that truthful, sensitive communication and where needed, a discussion about mortality, enables patients to take charge of their healthcare decisions, plan their affairs and steer away from unnecessarily aggressive therapies. Contrary to popular fears, patients attest that awareness of dying does not lead to greater sadness, anxiety or depression. It also does not hasten death. There is evidence that in the aftermath of death, bereaved family members report less anxiety and depression if they were included in conversations about dying. By and large, honesty does seem the best policy.

Studies worryingly show that a majority of patients are unaware of a terminal prognosis, either because they have not been told or because they have misunderstood the information. Somewhat disappointingly, oncologists who communicate honestly about a poor prognosis may be less well liked by their patient. But when we gloss over prognosis, it’s understandably even more difficult to tread close to the issue of just how one might die.

Thanks to advances in medicine, many cancer patients don’t die and the figures keep improving. Two thirds of patients diagnosed with cancer in the rich world today will survive five years and those who reach the five-year mark will improve their odds for the next five, and so on. But cancer is really many different diseases that behave in very different ways. Some cancers, such as colon cancer, when detected early, are curable. Early breast cancer is highly curable but can recur decades later. Metastatic prostate cancer, kidney cancer and melanoma, which until recently had dismal treatment options, are now being tackled with increasingly promising therapies that are yielding unprecedented survival times.

But the sobering truth is that advanced cancer is incurable and although modern treatments can control symptoms and prolong survival, they cannot prolong life indefinitely. This is why I think it’s important for anyone who wants to know, how cancer patients actually die.

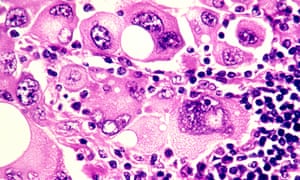

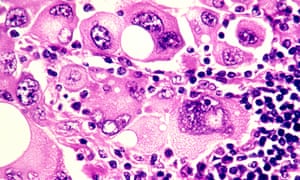

‘Cancer cells release a plethora of chemicals that inhibit appetite and affect the digestion and absorption of food’ Photograph: Phanie / Alamy/Alamy

“Failure to thrive” is a broad term for a number of developments in end-stage cancer that basically lead to someone slowing down in a stepwise deterioration until death. Cancer is caused by an uninhibited growth of previously normal cells that expertly evade the body’s usual defences to spread, or metastasise, to other parts. When cancer affects a vital organ, its function is impaired and the impairment can result in death. The liver and kidneys eliminate toxins and maintain normal physiology – they’re normally organs of great reserve so when they fail, death is imminent.

Cancer cells release a plethora of chemicals that inhibit appetite and affect the digestion and absorption of food, leading to progressive weight loss and hence, profound weakness. Dehydration is not uncommon, due to distaste for fluids or an inability to swallow. The lack of nutrition, hydration and activity causes rapid loss of muscle mass and weakness. Metastases to the lung are common and can cause distressing shortness of breath – it’s important to understand that the lungs (or other organs) don’t stop working altogether, but performing under great stress exhausts them. It’s like constantly pushing uphill against a heavy weight.

Cancer patients can also die from uncontrolled infection that overwhelms the body’s usual resources. Having cancer impairs immunity and recent chemotherapy compounds the problem by suppressing the bone marrow. The bone marrow can be considered the factory where blood cells are produced – its function may be impaired by chemotherapy or infiltration by cancer cells.Death can occur due to a severe infection. Pre-existing liver impairment or kidney failure due to dehydration can make antibiotic choice difficult, too.

You may notice that patients with cancer involving their brain look particularly unwell. Most cancers in the brain come from elsewhere, such as the breast, lung and kidney. Brain metastases exert their influence in a few ways – by causing seizures, paralysis, bleeding or behavioural disturbance. Patients affected by brain metastases can become fatigued and uninterested and rapidly grow frail. Swelling in the brain can lead to progressive loss of consciousness and death.

In some cancers, such as that of the prostate, breast and lung, bone metastases or biochemical changes can give rise to dangerously high levels of calcium, which causes reduced consciousness and renal failure, leading to death.

Uncontrolled bleeding, cardiac arrest or respiratory failure due to a large blood clot happen – but contrary to popular belief, sudden and catastrophic death in cancer is rare. And of course, even patients with advanced cancer can succumb to a heart attack or stroke, common non-cancer causes of mortality in the general community.

You may have heard of the so-called “double effect” of giving strong medications such as morphine for cancer pain, fearing that the escalation of the drug levels hastens death. But experts say that opioids are vital to relieving suffering and that they typically don’t shorten an already limited life.

It’s important to appreciate that death can happen in a few ways, so I wanted to touch on the important topic of what healthcare professionals can do to ease the process of dying.

In places where good palliative care is embedded, its value cannot be overestimated. Palliative care teams provide expert assistance with the management of physical symptoms and psychological distress. They can address thorny questions, counsel anxious family members, and help patients record a legacy, in written or digital form. They normalise grief and help bring perspective at a challenging time.

People who are new to palliative care are commonly apprehensive that they will miss out on effective cancer management but there is very good evidence that palliative care improves psychological wellbeing, quality of life, and in some cases, life expectancy. Palliative care is a relative newcomer to medicine, so you may find yourself living in an area where a formal service doesn’t exist, but there may be local doctors and allied health workers trained in aspects of providing it, so do be sure to ask around.

Finally, a word about how to ask your oncologist about prognosis and in turn, how you will die. What you should know is that in many places, training in this delicate area of communication is woefully inadequate and your doctor may feel uncomfortable discussing the subject. But this should not prevent any doctor from trying – or at least referring you to someone who can help.

Accurate prognostication is difficult, but you should expect an estimation in terms of weeks, months, or years. When it comes to asking the most difficult questions, don’t expect the oncologist to read between the lines. It’s your life and your death: you are entitled to an honest opinion, ongoing conversation and compassionate care which, by the way, can come from any number of people including nurses, social workers, family doctors, chaplains and, of course, those who are close to you.

Over 2,000 years ago, the Greek philosopher Epicurus observed that the art of living well and the art of dying well were one. More recently, Oliver Sacks reminded us of this tenet as he was dying from metastatic melanoma. If die we must, it’s worth reminding ourselves of the part we can play in ensuring a death that is peaceful.

Aditya Chakrabortty in The Guardian

IMF economists have published a remarkable paper admitting that the ideology was oversold

‘You hear it when the Bank of England’s Mark Carney sounds the alarm about ‘a low-growth, low-inflation, low-interest-rate equilibrium’. Photograph: Dylan Martinez/AFP/Getty Images

What does it look like when an ideology dies? As with most things, fiction can be the best guide. In Red Plenty, his magnificent novel-cum-history of the Soviet Union, Francis Spufford charts how the communist dream of building a better, fairer society fell apart.

Even while they censored their citizens’ very thoughts, the communists dreamed big. Spufford’s hero is Leonid Kantorovich, the only Soviet ever to win a Nobel prize for economics. Rattling along on the Moscow metro, he fantasises about what plenty will bring to his impoverished fellow commuters: “The women’s clothes all turning to quilted silk, the military uniforms melting into tailored grey and silver: and faces, faces the length of the car, relaxing, losing the worry lines and the hungry looks and all the assorted toothmarks of necessity.”

But reality makes swift work of such sandcastles. The numbers are increasingly disobedient. The beautiful plans can only be realised through cheating, and the draughtsmen know it better than any dissidents. This is one of Spufford’s crucial insights: that long before any public protests, the insiders led the way in murmuring their disquiet. Whisper by whisper, memo by memo, the regime is steadily undermined from within. Its final toppling lies decades beyond the novel’s close, yet can already be spotted.

When Red Plenty was published in 2010, it was clear the ideology underpinning contemporary capitalism was failing, but not that it was dying. Yet a similar process as that described in the novel appears to be happening now, in our crisis-hit capitalism. And it is the very technocrats in charge of the system who are slowly, reluctantly admitting that it is bust.

You hear it when the Bank of England’s Mark Carney sounds the alarm about “a low-growth, low-inflation, low-interest-rate equilibrium”. Or when the Bank of International Settlements, the central bank’s central bank, warns that “the global economy seems unable to return to sustainable and balanced growth”. And you saw it most clearly last Thursday from the IMF.

What makes the fund’s intervention so remarkable is not what is being said – but who is saying it and just how bluntly. In the IMF’s flagship publication, three of its top economists have written an essay titled “Neoliberalism: Oversold?”.

The very headline delivers a jolt. For so long mainstream economists and policymakers have denied the very existence of such a thing as neoliberalism, dismissing it as an insult invented by gap-toothed malcontents who understand neither economics nor capitalism. Now here comes the IMF, describing how a “neoliberal agenda” has spread across the globe in the past 30 years. What they mean is that more and more states have remade their social and political institutions into pale copies of the market. Two British examples, suggests Will Davies – author of the Limits of Neoliberalism – would be the NHS and universities “where classrooms are being transformed into supermarkets”. In this way, the public sector is replaced by private companies, and democracy is supplanted by mere competition.

The results, the IMF researchers concede, have been terrible. Neoliberalism hasn’t delivered economic growth – it has only made a few people a lot better off. It causes epic crashes that leave behind human wreckage and cost billions to clean up, a finding with which most residents of food bank Britain would agree. And while George Osborne might justify austerity as “fixing the roof while the sun is shining”, the fund team defines it as “curbing the size of the state … another aspect of the neoliberal agenda”. And, they say, its costs “could be large – much larger than the benefit”.

IMF managing director Christine Lagarde with George Osborne. ‘Since 2008, a big gap has opened up between what the IMF thinks and what it does.’ Photograph: Kimimasa Mayama/EPA

Two things need to be borne in mind here. First, this study comes from the IMF’s research division – not from those staffers who fly into bankrupt countries, haggle over loan terms with cash-strapped governments and administer the fiscal waterboarding. Since 2008, a big gap has opened up between what the IMF thinks and what it does. Second, while the researchers go much further than fund watchers might have believed, they leave in some all-important get-out clauses. The authors even defend privatisation as leading to “more efficient provision of services” and less government spending – to which the only response must be to offer them a train ride across to Hinkley Point C.

Even so, this is a remarkable breach of the neoliberal consensus by the IMF. Inequality and the uselessness of much modern finance: such topics have become regular chew toys for economists and politicians, who prefer to treat them as aberrations from the norm. At last a major institution is going after not only the symptoms but the cause – and it is naming that cause as political. No wonder the study’s lead author says that this research wouldn’t even have been published by the fund five years ago.

From the 1980s the policymaking elite has waved away the notion that they were acting ideologically – merely doing “what works”. But you can only get away with that claim if what you’re doing is actually working. Since the crash, central bankers, politicians and TV correspondents have tried to reassure the public that this wheeze or those billions would do the trick and put the economy right again. They have riffled through every page in the textbook and beyond – bank bailouts, spending cuts, wage freezes, pumping billions into financial markets – and still growth remains anaemic.

And the longer the slump goes on, the more the public tumbles to the fact that not only has growth been feebler, but ordinary workers have enjoyed much less of its benefits. Last year the rich countries’ thinktank, the OECD, made a remarkable concession. It acknowledged that the share of UK economic growth enjoyed by workers is now at its lowest since the second world war. Even more remarkably, it said the same or worse applied to workers across the capitalist west.

Red Plenty ends with Nikita Khrushchev pacing outside his dacha, to where he has been forcibly retired. “Paradise,” he exclaims, “is a place where people want to end up, not a place they run from. What kind of socialism is that? What kind of shit is that, when you have to keep people in chains? What kind of social order? What kind of paradise?”

Economists don’t talk like novelists, more’s the pity, but what you’re witnessing amid all the graphs and technical language is the start of the long death of an ideology.

Rohit Brijnath in The Straits Times

My father, 81, and I talk occasionally about his death. At breakfast he, not an ailing man, can turn into a prophet of doom amidst spoonfuls of cereal. "I have two years left," he will pronounce, to which I reply that his predictions are unreliable since he has been saying this for the past six years. My mother, 83, laughs and he smiles. We are all, impossibly, trying to meet death with some humour and grace.

I am sounding braver than I actually feel for the inevitability of a parent's death is like a shadow that walks quietly with most of us. A 40-year-old woman I met recently revealed that when her parents are asleep, she stands over their beds in the dark, waiting for a tiny movement, a proof of life. Mortality is life's most towering lesson, not to be feared but gradually understood.

My parents' eventual death is hardly a preoccupation for me but for those of us who live on foreign shores, it's always there, lingering on the outskirts of our daily lives. It is hard to explain the two-second terror of the surprise phone call from our homes far away. I answer with a question that is always tense and terse: "Everything OK?" My father replies: "Of course, beta (son)."

Death will come, and somehow, it will always be imperfect. In old Bollywood films, parents made long, weepy speeches about family and love and then their heads fell dramatically to the side. Reality is never so scripted. The devilry of distance - I live two flights from my parents - means that it is unlikely we will be home in time. We do not want our parents to linger and yet the heart attack's unpredictable finality leaves no time for farewell. We are presuming, of course, that there is such a thing as a graceful goodbye. Perhaps it is in how we live with them that is more vital.

I talk occasionally to my parents about death, not because I am morbid but because I am inquisitive about mortality and because I do not want them to be scared or alone. Yet I find it is they who reassure me.

They return from frequent funerals, friends gone and family lost, and speak with voice softer but spirit intact. My father retreats deeper into his sofa and philosophy and tells me: "The whole, wonderful, joyful, exhilarating business of evolution would not exist if we were immortal." There can rarely be an equanimity about death - we all fear pain and indignity on the way there and we all feel loss - but sometimes we might strive for an acceptance that all things must finish.

Few other struggles are as impartial as ageing and illness, and the mortality of a parent. Every friend I spoke to carried a separate apprehension. A banker told me she is unafraid and yet had already asked close friends to attend her parents' funerals. Emotionally and practically, she knows she will need support. An executive, her parents still together after 61 years, sinks as she considers one parent left behind, like an old, steadied ship whose moorings have been cruelly cut. A flinty investigative journalist, bound to her mother who is her only parent alive, wonders about her sanity once left alone.

We feel hesitant often to raise some subjects with our parents as if they are too impertinent or inconvenient and yet practicality has a place. Was a will written, a DNR (Do Not Resuscitate) ordered, all these seemingly minor matters which leave shaken families divided in emergency rooms. Do we know what our parents wish and how they want to go?

Clarity is the great courtesy that my friend Sharda's mother offered her: no life support, no unnecessary surgery. Another pal, Samar, has a paper packet at home given to him a while ago by his parents and only recently did he find the nerve to peek in. No religious rituals, his parents wrote; our bodies to be donated for medical purposes, they noted.

I found nothing grim in this but saw it instead as a gentle gift to their son by giving him answers to questions he cannot bear to ask. There was also in the giving of their bodies to science a beautiful, moral clarity. In their 80s, they had understood that in death, they might be able to do what so few of us can do while living: save a life.

Samar sees his parents every day and I call India every second day. In my wrestle with the eventual truth of a parent-less planet, I have learnt five things. The first is contact. To hear, see, touch. To talk and to learn. My father recently mentioned in conversation about the composers Johann Strauss Senior and Junior. I didn't tell him I thought there was only one. So thanks, dad.

Second, to speak your mind, to leave nothing unsaid, for in the sharing of love a relationship comes alive. Not everyone can find the words but regret is an incurable ache.

Third, mine them for stories, of where they came from, hardship they hurdled, love they found, museums they visited, people they became, dreams they left behind, times they lived in, fears they wore. If I don't write them down, then stories dim and histories die and there is nothing to carry forward.

Fourth, and this my mother is teaching me, is to respect choice. "Fight, fight" against age, against illness, we tell our parents, often selfishly, but not everything must be raged against. Dylan Thomas was wrong, sometimes you have to go gentle into that good night. Sometimes, life has been enough, a weariness comes to rest, all accounts are settled and people want to turn to the wall, away from life and slip away. As my closest friend, Namita, still grieving over a mother she recently lost, told me: "There is a great love in letting people go."

Fifth, and I am lousy at this, don't steal their autonomy and instead respect their choices, hear their opinions, let them be free to arrange the rhythms of their life. My brothers and I are always trying to buy our parents a TV, a fridge, as if we cannot fathom that their life does not need a new shine. Yet it is fine as it is. So what if the letters on my mother's keyboard wore away, she has not forgotten the unique order of this alphabet.

Still I search for clarity amidst the clutter of life's incessant questions. I wade, like us all, through the truths of ageing and loss. I think of a relative who cannot find a way to open cupboards and wander through the accumulated life of her parents she has recently lost. I am moved by a friend, a civil servant whose father passed away a while ago and who tells me: "I don't fear death. I feel I have had a fulfilling stint with my mum." We are, all of us, a forest of crooked trees, leaning on each other.

I find reassurance in the reality that my parents, hardly wealthy, not poor, have lived rich lives. My mother now sits with the stillness of a painting and reads. My father writes to me: "I am not frightened by death. I will be sad that I can no longer look at Michelangelo's David, Picasso's Guernica, listen to the cool jazz of Bill Evans' piano or smell the aroma of a beautiful woman!" Today he has gone, as he does many Sundays, to listen and learn from a younger man about his beloved Strauss and Bach and Mozart. To this music, always he comes alive.

A rise in atheist funerals shows that fewer of us need to rely on faith when confronted with mortality

Adam Lee in The Guardian

For centuries, the Christian church wrote the script for how westerners deal with death. There was the deathbed confession, the last rites, the pallbearers, the obligatory altar call, the burial ceremony, the stone, the angels-and-harps imagery. Yet that archaic and stereotypical vision of death, like a mossy and weather-worn statue, is crumbling – and in its place, something new and better has a chance to grow.

Traditional funerals and burials are declining in popularity (to the point where churches are bemoaning the trend), in favor of alternatives like green burial and cremation. Personalized humanist funerals and secular celebrants are becoming more common, echoing a trend that’s also occurring with weddings.

As younger generations turn away from religion, the US is slowly but surely becoming more secular. As mortician and “good death” advocate Caitlin Doughty writes in her book, Smoke Gets In Your Eyes & Other Lessons from the Crematory, America is seeing a sea-change in traditions and rituals surrounding mortality.

Doughty and others see this shift not as something to be lamented, but to be embraced. Instead of following a script that’s been written for us, we can create our own customs and choose for ourselves how we want to be remembered. We can design funerals that emphasize the good we did, the moments that made our lives meaningful and the lessons we’d like to pass on.

Rather than the same handful of biblical passages, we can have readings from any book, poem or song in the whole broad tapestry of human culture. Rather than mourning, gloom and sermons on sin, we can have ceremonies that are joyful celebrations of the deceased person’s life.

But the rise of humanism isn’t just influencing what funerals look like; it’s changing how we die. For ages, when the church’s word was law, suicide was deemed a mortal sin. Even today, studies find that more fervent religious devotion correlates to more desire for aggressive and medically futile end-of-life intervention, not less.

The most famous case in recent years was Brittany Maynard, a 29-year-old woman with terminal brain cancer who ended her life in 2014 under Oregon’s death-with-dignity law. Maynard’s story put a sympathetic public face on the right-to-die movement, which proved decisive when California Governor Jerry Brown, a former Jesuit seminarian, signed a similar bill the next year despite heavy pressure from religious groups. He, too, cited the value of autonomy and freedom from suffering:

“In the end, I was left to reflect on what I would want in the face of my own death,” Brown wrote in a signing message. “I do not know what I would do if I were dying in prolonged and excruciating pain” he added.

In California and elsewhere, the staunchest adversaries of the right to die are churches and religious believers who assert that the time, place and manner of each person’s death is chosen by God, and that we have no right to change that regardless of the human cost.

And yet, almost without notice, that’s become a minority position. Gallup polls now find that as many as 70% of Americans now support a right to aid in dying. This position entails that, when people are suffering without hope of recovery, they should be allowed to end their lives painlessly, with medical help, at a time of their choosing.

This, too, is a deeply humanist conception of death. It springs from the idea that needless suffering is the greatest evil there is and that autonomy is the supreme value. If we’re the ultimate owners of our own lives, then we have the right to lay them down when we judge they’ve become unbearable.

Even as religious trappings linger in our rituals and attitudes around death, society is coming to adopt the humanist viewpoint on mortality, neither fearing nor denying it, but gracefully accepting it as an inevitable part of the human experience. The sooner we bury our religious past, the better.

Aman Sethi in The Guardian

On the night of 7 January 2012, a stationmaster at a provincial railway station in central India discovered the body of a young woman lying beside the tracks. The corpse, clothed in a red kurta and a violet and grey Puma jacket, was taken to a local morgue, where a postmortem report classified the death as a homicide.

The unidentified body was “a female aged about 21 to 25 years”, according to the postmortem, which described “dried blood present” in the nostrils, and the “tongue found clenched between upper and lower jaw, two upper teeth found missing, lips found bruised”. There was a crescent of scratches on the young woman’s face, as if gouged by the fingernails of a hand forcefully clamped over her mouth. “In our opinion,” the handwritten report concluded, “[the] deceased died of asphyxia (violent asphyxia) as a result of smothering.”

Three weeks later, a retired schoolteacher, Mehtab Singh Damor, identified the body as his 19-year-old daughter Namrata Damor – who had been studying medicine at the Mahatma Gandhi Medical College in Indore before she suddenly vanished one morning in early January 2012. Damor demanded an investigation to find his daughter’s killer, but the police dismissed the findings of the initial postmortem, and labelled her death a suicide.

The case was closed – until this July, more than three years later, when a 38-year-old television reporter named Akshay Singh travelled from Delhi to the small Madhya Pradesh town of Meghnagar to interview Namrata’s father. Singh thought that Namrata’s mysterious death might be connected to an extraordinary public scandal, known as the Vyapam scam, which had roiled the highest echelons of the government of Madhya Pradesh.

For at least five years, thousands of young men and women had paid bribes worth millions of pounds in total to a network of fixers and political operatives to rig the official examinations run by the Madhya Pradesh Vyavsayik Pariksha Mandal – known as Vyapam – a state body that conducted standardised tests for thousands of highly coveted government jobs and admissions to state-run medical colleges. When the scandal first came to light in 2013, it threatened to paralyse the entire machinery of the state administration: thousands of jobs appeared to have been obtained by fraudulent means, medical schools were tainted by the spectre of corrupt admissions, and dozens of officials were implicated in helping friends and relatives to cheat the exams.

A fevered investigation began, and hundreds of arrests were made

A fevered investigation began, and hundreds of arrests were made. But Singh suspected that the unsolved murder of Namrata Damor – and the baffling insistence of the police that she had flung herself from a moving train – might be part of a massive cover-up, intended to protect senior political figures, all the way up to the powerful chief minister of Madhya Pradesh.