'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Monday, 20 November 2023

Saturday, 4 November 2023

Friday, 29 September 2023

Wednesday, 16 August 2023

Thursday, 1 September 2022

Why intellectual humility matters

What makes some people believe in conspiracy theories and false news reports more than others? Is it their political or religious perspective? Is it a lack of formal education? Or is it more about their age, gender or socio-economic background?

Thursday, 2 September 2021

Monday, 17 May 2021

Why the suspicion on China’s Wuhan lab virus is growing

Tara Kartha in The Print

It’s been nearly eighteen months since the coronavirus brought the world on its knees, with India in the middle of a deadly second wave that is claiming 4,000 lives daily on an average. No one can tell when this will end. But it is possible to probe how this catastrophe began, and China’s role in it. Fortunately, even as cover ups go on. Several reports are out in the public domain and anybody who isn’t afraid of speaking the truth should be able to connect the dots.

One report out is that of the Independent Panel, set up by a resolution of the 73rd World Health Assembly. The specific mission of the committee was to review the response of the World Health Organization (WHO) to the Covid outbreak and the timelines relevant. In other words, it was never meant to be an inquisition on China. And it wasn’t. Not by a long chalk. It went around the core question of the origin of the virus, even while indulging in what seems to be pure speculation. Then there are two recent publications investigating the origin of the virus, which are worthy of note. Neither are written by sage scientists, but by analysts viewing the whole sequence of events through the prism of intelligence. Which means that these efforts skip the big words, and get to the facts. Collate all these different sources, add a little more of the background colour, and you start to get the big picture.

Is this biological warfare?

The need to find out the truth becomes urgent as the situation worsens, for instance with dangerously high death rates in Aligarh Muslim University, where there is now speculation whether the deaths could be linked to a separate strain. There are arguments that India’s second wave could be a deliberate one, especially since the ‘double mutant’ has not hit any of its neighbours. Such speculation is likely to rise, given that China has now effectively closed any possibility of withdrawal from Ladakh, and the Chinese economy goes from strength to strength, growing a record 18.3 per cent in the first quarter of the new financial year. Unsurprisingly, even world leaders, like Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro, have linked the pandemic to biological warfare.

Arising from this is the biggest potential danger: someone may decide to respond in kind in a bid to fix Beijing. That’s how intelligence operations work. After all, major countries haven’t been funding their top secret labs for nothing. In any scenario, there’s some serious trouble ahead, especially since the Narendra Modi government seems to be more intent on playing down the crisis than addressing it.

The Independent Panel

The panel’s mandate is set out clearly in the May 2020 resolution, which calls for “a stepwise process of impartial, independent and comprehensive evaluation…to review experience gained and lessons learned from the WHO-coordinated international health response to COVID-19…” and thereafter provide recommendations. This the panel undoubtedly did.

The 13-member panel included former Prime Minister of New Zealand Helen Clark, former President of Liberia who has core expertise in setting up health care after Ebola, an award winning feminist, a former WHO bureaucrat, and a former Indian health secretary, who had six months experience in handling the first Covid wave, was on innumerable panels on health, and in the manner of civil servants in this country, also did a stint in the Ministry of Defence, not to mention the World Bank. The Indian representative certainly gives the whole exercise the imprimatur of legality, given hostile India-China relations. And finally, Zhong Nanshan who was advisor to the Chinese government during the Wuhan outbreak, and who received the highest State honour of the Medal of the Republic from his President—Xinhua describes him as a “brave and outspoken” doctor.

The WHO also lists Peng Liyuan as a Goodwill Ambassador, describing her as a famous opera singer. She is the wife of President Xi Jinping. It’s,therefore, entirely unsurprising that while the panel diligently shows WHO the sources of early warning, it makes a vague case on the origins of the virus, noting that while a species of bat was “probably” the host, the intermediate cycle is unknown. Most astonishingly, the committee states that the virus “may already have been in circulation outside China in the last months of 2019”. No evidence for that either. The overall tenor of the report is that it would take years to sort all this out.

There is only one paragraph of note from the point of view of those seeking the truth.

The panel’s report states that less than 55–60 per cent of early cases had been exposed to the wet markets, and that the area merely “amplified” the virus. In other words, the market, with its hundreds of exotic wildlife, could not have been the source. It, however, carefully notes that the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) sequenced the entire genome of the virus almost within weeks, and later provided this to a public access source. The report praises the diligence of clinicians who managed to isolate the virus within a short time. That’s wonderful all right. No question. But it doesn’t at all address the question whether those diligent researchers were also experimenting on the virus.

That troubling question

These assessments by the Independent Panel are now, however, being questioned, leading to bits of intelligence being pieced together from within a country that would put the term ‘Iron curtain’ to shame. An earlier WHO study on the virus’ origin was roundly condemned by a group of countries,including the US, Australia, Canada and others (not India) as being duplicitous in the extreme.

In January 2021, the US Department of State released a Fact Sheet on activity of WIV, which is entirely based on intelligence. That factsheet is damning, indicating that several researchers at the institute had fallen ill with characteristics of the Covid virus, thus showing up senior Chinese researcher Shi Zhengli’s claim that there was “zero infection” in the lab. The lab was the centre of research of the SARS virus since its first outbreak, including on ‘RaTG13’ virus found in bats, and which is 96 per cent similar to the present virus SARS-COV-2. Worst, it also pointed out that “the United States has determined that the WIV has collaborated on publications and secret projects with China’s military. The WIV has engaged in classified research, including laboratory animal experiments, on behalf of the Chinese military since at least 2017”.

That’s intelligence. Now for the analysis — the two recent publications probing the virus’ origin.

Disaggregating the facts

One analytical article is published in the prestigious Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Another is a paper by the equally reputed Begin Sadat Centre for Strategic Studies. Both are a careful collation of facts, and establish the following.

The paper by Begin Sadat Centre brings out additional information that bolsters the US Fact Sheet. It appears that the US had been able to get a ‘source’ from WIV directly, and that another Chinese scientist had defected to an unknown European country. That led directly to information on the military side of the programme. The study also quotes David Asher, who led the Department of State investigation. Asher observes that the WIV had two campuses, not one, as popularly believed. This was known by the Indian authorities for years, but does not seem to have been put about. Asher also adds that all mention of the SARS virus was dropped from the institute’s publicly admitted biological “defence programmes” by 2017 at the same time when the Level 4 lab kicked off operations.

Even more surprising was that an adjacent facility had already administered vaccines to its senior faculty in March 2020 itself. That doesn’t suggest an accident. That suggests a program that was designed to kill, and for which vaccines were already under research. Then there damning studies stated: “There are plenty of indications in the sequence itself that [the initial pandemic virus] may have been synthetically altered. It has the backbone of a bat [coronavirus], combined with a pangolin receptor binder, combined with some sort of humanized mice transceptor. These things don’t actually make sense (and) …..the odds this could be natural are very low… [but this is attainable] through deliberate scientific ‘gain of function research” that was going on at the WIV.

There is no doubt that ‘gain of function’ research is practised in biological research labs world over, resulting in, sometimes, dangerous incidents. This type of research involves in-crossing viruses, ostensibly to gain knowledge on how to battle the disease from within. In these cases, it’s almost impossible to decide where the ‘defence’ aspect leaches into an offensive capability. That these findings were from US scientists who were ‘fearful’ of being quoted shows not just the extent of Beijing’s clout in university research and funding, but also a high degree of restraint. Biological research is almost never talked about.

The denials begin

Biological research and the secrecy around it is the aspect of focus in Nicholas Wade’s article published in Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. As he writes, from the beginning, there was denial at the highest levels from some unexpected quarters. The first was in The Lancet— one of the oldest journals of medical research—by a group of authors in March 2020, when the pandemic had just broken out. Even to a layman, it would have seemed that it was far too early for the group of authors to contemptuously dismiss ‘conspiracy theories’ that the virus was not of a natural origin.

It turns out that The Lancet letter was drafted by Peter Daszak, President of the EcoHealth Alliance of New York, who’s organisation funded corona virus research at the Wuhan lab. As is pointed out in Wade’s article, any revelation of such a connection would have been criminal to say the least, if it was proved that the virus did escape from the lab. Unsurprisingly, Daszak was also part of the WHO team investigating the origins of the virus.

Another burst of outrage came from a group of professors who also hurried to disprove, in an article, the ‘lab created’ theory on the grounds – simply put – that it was not of the most probably calculated design. The lead author Kristian G Anderson is from the Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, which specialises in biomedical research. It also has partnerships with Chinese labs and pharma companies. None of that is criminal. Especially when Scrippsis already in financial distress at the time. Besides, such collaborations are not restricted to just US labs. See, for instance, an account of Australian doctor Dominic Dwyer, who was part of the first WHO study, and who dismissed without any evidence presented that the virus had leaked from a lab.

Dwyer’s claim that the Wuhan lab seems to have been run well, and that nobody from the facility seemed to have fallen sick has now been disputed. Evidence of a dangerous virus escaping a lab – as it has in the past on what he calls “rare” occasions – would mean a death blow to labs everywhere. Funding is, after all, hard to come by. Then there is the nice hard cash involved. The Harvard professor Dr Charles Leiber who was arrested, together with two other Chinese, for collaborating quietly with the Wuhan University of Technology (WUT), was being paid roughly $50,000 per month, living expenses of up to 1,000,000 Chinese Yuan (approximately $158,000) and awarded $1.5 million to establish a research lab at WUT. He was also asked to ‘cultivate’ young teachers and Ph.D. students by organising international conferences.

It’s all very pally and friendly, and a lot of money is involved. The end result? A virus out of hell, that seems not to affect the Chinese as its economy powers ahead and shifts its weight more comfortably into its rising position in the global order.

Sunday, 21 March 2021

DECODING DENIALISM

On November 12, 2009, the New York Times (NYT) ran a video report on its website. In it, the NYT reporter Adam B. Ellick interviewed some Pakistani pop stars to gauge how lifestyle liberals were being affected by the spectre of so-called ‘Talibanisation’ in Pakistan. To his surprise, almost every single pop artiste that he managed to engage, refused to believe that there were men willing to blow themselves up in public in the name of faith.

It wasn’t an outright denial, as such, but the interviewed pop acts went to great lengths to ‘prove’ that the attacks were being carried out at the behest of the US, and that those who were being called ‘terrorists’ were simply fighting for their rights. Ellick’s surprise was understandable. Between 2007 and 2009, hundreds of people had already been killed in Pakistan by suicide bombers.

But it wasn’t just these ‘confused’ lifestyle liberals who chose to look elsewhere for answers when the answer was right in front of them. Unregulated talk shows on TV news channels were constantly providing space to men who would spin the most ludicrous narratives that presented the terrorists as ‘misunderstood brothers.’

From 2007 till 2014, terrorist attacks and assassinations were a daily occurrence. Security personnel, politicians, men, women and children were slaughtered. Within hours, the cacophony of inarticulate noises on the electronic media would drown out these tragedies. The bottom-line of almost every such ‘debate’ was always, ‘ye hum mein se nahin’ [these (terrorists) are not from among us]. In fact, there was also a song released with this as its title and ‘message.’

The perpetrators of the attacks were turned into intangible, invisible entities, like characters of urban myths that belong to a different realm. The fact was that they were very much among us, for all to see, even though most Pakistanis chose not to.

Just before the 2013 elections, the website of an English daily ran a poll on the foremost problems facing Pakistan. The poll mentioned unemployment, corruption, inflation and street crimes, but there was no mention of terrorism even though, by 2013, thousands had been killed in terrorist attacks.

So how does one explain this curious refusal to acknowledge a terrifying reality that was operating in plain sight? In an August 3, 2018 essay for The Guardian, Keith Kahn-Harris writes that individual self-deception becomes a problem when it turns into ‘public dogma.’ It then becomes what is called ‘denialism.’

The American science journalist and author Michael Specter, in his book Denialism, explains it to mean an entire segment of society, when struggling with trauma, turning away from reality in favour of a more comfortable lie. Psychologists have often explained denial as a coping mechanism that humans use in times of stress. But they also warn that if denial establishes itself as a constant disposition in an individual or society, it starts to inhibit the ability to resolve the source of the stress.

Denialism, as a social condition, is understood by sociologists as an undeclared ‘ism’, adhered to by certain segments of a society whose rhetoric and actions in this context can impact a country’s political, social and even economic fortunes.

In the January 2009 issue of European Journal of Public Health, Pascal Diethelm and Martin McKee write that the denialism process employs five main characteristics. Even though Diethelm and McKee were more focused on the emergence of denialism in the face of evidence in scientific fields of research, I will paraphrase four out of the five stated characteristics to explore denialism in the context of extremist violence in Pakistan from 2007 till 2017.

The deniers have their own interpretation of the same evidence. In early 2013, when a study showed that 1,652 people had been killed in 2012 alone in Pakistan because of terrorism, an ‘analyst’ on a news channel falsely claimed that these figures included those killed during street crimes and ‘revenge murders.’ Another gentleman insisted that the figures were concocted by foreign-funded NGOs ‘to give Pakistan and Islam a bad name.’

This brings us to denialism’s second characteristic: The use of fake experts. These are individuals who purport to be experts in a particular area but whose views are entirely inconsistent with established knowledge. During the peak years of terrorist activity in the country, self-appointed ‘political experts’ and ‘religious scholars’ were a common sight on TV channels. Their ‘expert opinions’ were heavily tilted towards presenting the terrorists as either ‘misunderstood brothers’ or people fighting to impose a truly Islamic system in Pakistan. Many such experts suddenly vanished from TV screens after the intensification of the military operation against militants in 2015. Some were even booked for hate speech.

The third characteristic is about selectivity, drawing on isolated opinions or highlighting flaws in the weakest opinions to discredit entire facts. In October 2012, when extremists attempted to assassinate a teenaged school girl, Malala Yousafzai, a sympathiser of the extremists on TV justified the assassination attempt by mentioning ‘similar incidents’ that he discovered in some obscure books of religious traditions. Within months Malala became the villain, even among some of the most ‘educated’ Pakistanis. When the nuclear physicist and intellectual Dr Pervez Hoodbhoy exhibited his disgust over this, he was not only accused of being ‘anti-Islam’, but his credibility as a scientist too was questioned.

The fourth characteristic is about misrepresenting the opposing argument to make it easier to refute. For example, when terrorists were wreaking havoc in Pakistan, the arguments of those seeking to investigate the issue beyond conspiracy theories and unabashed apologias, were deliberately misconstrued as being criticisms of religious faith.

Today we are seeing all this returning. But this time, ‘experts’ are appearing on TV pointing out conspiracies and twisting facts about the Covid-19 pandemic and vaccines. They are also offering their expert opinions on events such as the Aurat March and, in the process, whipping up a dangerous moral panic.

It seems, not much was learned by society’s collective disposition during the peak years of terrorism and how it delayed a timely response that might have saved hundreds of innocent lives.

Wednesday, 27 January 2021

Friday, 15 January 2021

Conspiracy theorists destroy a rational society: resist them

John Thornhill in The FT

Buzz Aldrin’s reaction to the conspiracy theorist who told him the moon landings never happened was understandable, if not excusable. The astronaut punched him in the face.

Few things in life are more tiresome than engaging with cranks who refuse to accept evidence that disproves their conspiratorial beliefs — even if violence is not the recommended response. It might be easier to dismiss such conspiracy theorists as harmless eccentrics. But while that is tempting, it is in many cases wrong.

As we have seen during the Covid-19 pandemic and in the mob assault on the US Congress last week, conspiracy theories can infect the real world — with lethal effect. Our response to the pandemic will be undermined if the anti-vaxxer movement persuades enough people not to take a vaccine. Democracies will not endure if lots of voters refuse to accept certified election results. We need to rebut unproven conspiracy theories. But how?

The first thing to acknowledge is that scepticism is a virtue and critical scrutiny is essential. Governments and corporations do conspire to do bad things. The powerful must be effectively held to account. The US-led war against Iraq in 2003, to destroy weapons of mass destruction that never existed, is a prime example.

The second is to re-emphasise the importance of experts, while accepting there is sometimes a spectrum of expert opinion. Societies have to base decisions on experts’ views in many fields, such as medicine and climate change, otherwise there is no point in having a debate. Dismissing the views of experts, as Michael Gove famously did during the Brexit referendum campaign, is to erode the foundations of a rational society. No sane passenger would board an aeroplane flown by an unqualified pilot.

In extreme cases, societies may well decide that conspiracy theories are so harmful that they must suppress them. In Germany, for example, Holocaust denial is a crime. Social media platforms that do not delete such content within 24 hours of it being flagged are fined.

In Sweden, the government is even establishing a national psychological defence agency to combat disinformation. A study published this week by the Oxford Internet Institute found “computational propaganda” is now being spread in 81 countries.

Viewing conspiracy theories as political propaganda is the most useful way to understand them, according to Quassim Cassam, a philosophy professor at Warwick university who has written a book on the subject. In his view, many conspiracy theories support an implicit or explicit ideological goal: opposition to gun control, anti-Semitism or hostility to the federal government, for example. What matters to the conspiracy theorists is not whether their theories are true, but whether they are seductive.

So, as with propaganda, conspiracy theories must be as relentlessly opposed as they are propagated.

That poses a particular problem when someone as powerful as the US president is the one shouting the theories. Amid huge controversy, Twitter and Facebook have suspended Donald Trump’s accounts. But Prof Cassam says: “Trump is a mega disinformation factory. You can de-platform him and address the supply side. But you still need to address the demand side.”

On that front, schools and universities should do more to help students discriminate fact from fiction. Behavioural scientists say it is more effective to “pre-bunk” a conspiracy theory — by enabling people to dismiss it immediately — than debunk it later. But debunking serves a purpose, too.

As of 2019, there were 188 fact-checking sites in more than 60 countries. Their ability to inject facts into any debate can help sway those who are curious about conspiracy theories, even if they cannot convince true believers.

Under intense public pressure, social media platforms are also increasingly filtering out harmful content and nudging users towards credible sources of information, such as medical bodies’ advice on Covid.

Some activists have even argued for “cognitive infiltration” of extremist groups, suggesting that government agents should intervene in online chat rooms to puncture conspiracy theories. That may work in China but is only likely to backfire in western democracies, igniting an explosion of new conspiracy theories.

Ultimately, we cannot reason people out of beliefs that they have not reasoned themselves into. But we can, and should, punish those who profit from harmful irrationality. There is a tried-and-tested method of countering politicians who peddle and exploit conspiracy theories: vote them out of office.

Friday, 14 June 2019

The mindfulness conspiracy - Is Meditation the enemy of Activism?

Mindfulness has gone mainstream, with celebrity endorsement from Oprah Winfrey and Goldie Hawn. Meditation coaches, monks and neuroscientists went to Davos to impart the finer points to CEOs attending the World Economic Forum. The founders of the mindfulness movement have grown evangelical. Prophesying that its hybrid of science and meditative discipline “has the potential to ignite a universal or global renaissance”, the inventor of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), Jon Kabat-Zinn, has bigger ambitions than conquering stress. Mindfulness, he proclaims, “may actually be the only promise the species and the planet have for making it through the next couple of hundred years”.

So, what exactly is this magic panacea? In 2014, Time magazine put a youthful blonde woman on its cover, blissing out above the words: “The Mindful Revolution.” The accompanying feature described a signature scene from the standardised course teaching MBSR: eating a raisin very slowly. “The ability to focus for a few minutes on a single raisin isn’t silly if the skills it requires are the keys to surviving and succeeding in the 21st century,” the author explained.

But anything that offers success in our unjust society without trying to change it is not revolutionary – it just helps people cope. In fact, it could also be making things worse. Instead of encouraging radical action, mindfulness says the causes of suffering are disproportionately inside us, not in the political and economic frameworks that shape how we live. And yet mindfulness zealots believe that paying closer attention to the present moment without passing judgment has the revolutionary power to transform the whole world. It’s magical thinking on steroids.

There are certainly worthy dimensions to mindfulness practice. Tuning out mental rumination does help reduce stress, as well as chronic anxiety and many other maladies. Becoming more aware of automatic reactions can make people calmer and potentially kinder. Most of the promoters of mindfulness are nice, and having personally met many of them, including the leaders of the movement, I have no doubt that their hearts are in the right place. But that isn’t the issue here. The problem is the product they’re selling, and how it’s been packaged. Mindfulness is nothing more than basic concentration training. Although derived from Buddhism, it’s been stripped of the teachings on ethics that accompanied it, as well as the liberating aim of dissolving attachment to a false sense of self while enacting compassion for all other beings.

What remains is a tool of self-discipline, disguised as self-help. Instead of setting practitioners free, it helps them adjust to the very conditions that caused their problems. A truly revolutionary movement would seek to overturn this dysfunctional system, but mindfulness only serves to reinforce its destructive logic. The neoliberal order has imposed itself by stealth in the past few decades, widening inequality in pursuit of corporate wealth. People are expected to adapt to what this model demands of them. Stress has been pathologised and privatised, and the burden of managing it outsourced to individuals. Hence the pedlars of mindfulness step in to save the day.

But none of this means that mindfulness ought to be banned, or that anyone who finds it useful is deluded. Reducing suffering is a noble aim and it should be encouraged. But to do this effectively, teachers of mindfulness need to acknowledge that personal stress also has societal causes. By failing to address collective suffering, and systemic change that might remove it, they rob mindfulness of its real revolutionary potential, reducing it to something banal that keeps people focused on themselves.

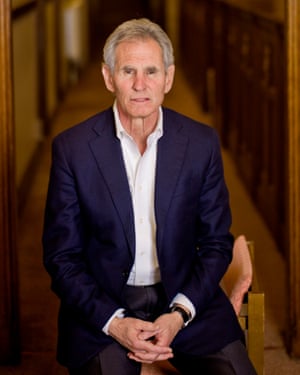

Jon Kabat-Zinn, who is often called the father of modern mindfulness. Photograph: Sarah Lee

The fundamental message of the mindfulness movement is that the underlying cause of dissatisfaction and distress is in our heads. By failing to pay attention to what actually happens in each moment, we get lost in regrets about the past and fears for the future, which make us unhappy. Kabat-Zinn, who is often labelled the father of modern mindfulness, calls this a “thinking disease”. Learning to focus turns down the volume on circular thought, so Kabat-Zinn’s diagnosis is that our “entire society is suffering from attention deficit disorder – big time”. Other sources of cultural malaise are not discussed. The only mention of the word “capitalist” in Kabat-Zinn’s book Coming to Our Senses: Healing Ourselves and the World Through Mindfulness occurs in an anecdote about a stressed investor who says: “We all suffer a kind of ADD.”

Mindfulness advocates, perhaps unwittingly, are providing support for the status quo. Rather than discussing how attention is monetised and manipulated by corporations such as Google, Facebook, Twitter and Apple, they locate the crisis in our minds. It is not the nature of the capitalist system that is inherently problematic; rather, it is the failure of individuals to be mindful and resilient in a precarious and uncertain economy. Then they sell us solutions that make us contented, mindful capitalists.

By practising mindfulness, individual freedom is supposedly found within “pure awareness”, undistracted by external corrupting influences. All we need to do is close our eyes and watch our breath. And that’s the crux of the supposed revolution: the world is slowly changed, one mindful individual at a time. This political philosophy is oddly reminiscent of George W Bush’s “compassionate conservatism”. With the retreat to the private sphere, mindfulness becomes a religion of the self. The idea of a public sphere is being eroded, and any trickledown effect of compassion is by chance. As a result, notes the political theorist Wendy Brown, “the body politic ceases to be a body, but is, rather, a group of individual entrepreneurs and consumers”.

Mindfulness, like positive psychology and the broader happiness industry, has depoliticised stress. If we are unhappy about being unemployed, losing our health insurance, and seeing our children incur massive debt through college loans, it is our responsibility to learn to be more mindful. Kabat-Zinn assures us that “happiness is an inside job” that simply requires us to attend to the present moment mindfully and purposely without judgment. Another vocal promoter of meditative practice, the neuroscientist Richard Davidson, contends that “wellbeing is a skill” that can be trained, like working out one’s biceps at the gym. The so-called mindfulness revolution meekly accepts the dictates of the marketplace. Guided by a therapeutic ethos aimed at enhancing the mental and emotional resilience of individuals, it endorses neoliberal assumptions that everyone is free to choose their responses, manage negative emotions, and “flourish” through various modes of self-care. Framing what they offer in this way, most teachers of mindfulness rule out a curriculum that critically engages with causes of suffering in the structures of power and economic systems of capitalist society.

The term “McMindfulness” was coined by Miles Neale, a Buddhist teacher and psychotherapist, who described “a feeding frenzy of spiritual practices that provide immediate nutrition but no long-term sustenance”. The contemporary mindfulness fad is the entrepreneurial equal of McDonald’s. The founder of McDonald’s, Ray Kroc, created the fast food industry. Very early on, when he was selling milkshakes, Kroc spotted the franchising potential of a restaurant chain in San Bernadino, California. He made a deal to serve as the franchising agent for the McDonald brothers. Soon afterwards, he bought them out, and grew the chain into a global empire. Kabat-Zinn, a dedicated meditator, had a vision in the midst of a retreat: he could adapt Buddhist teachings and practices to help hospital patients deal with physical pain, stress and anxiety. His masterstroke was the branding of mindfulness as a secular spirituality.

Kroc saw his chance to provide busy Americans with instant access to food that would be delivered consistently through automation, standardisation and discipline. Kabat-Zinn perceived the opportunity to give stressed-out Americans easy access to MBSR through an eight-week mindfulness course for stress reduction that would be taught consistently using a standardised curriculum. MBSR teachers would gain certification by attending programmes at Kabat-Zinn’s Center for Mindfulness in Worcester, Massachusetts. He continued to expand the reach of MBSR by identifying new markets such as corporations, schools, government and the military, and endorsing other forms of “mindfulness-based interventions” (MBIs).

Both men took measures to ensure that their products would not vary in quality or content across franchises. Burgers and fries at McDonald’s are the same whether one is eating them in Dubai or in Dubuque. Similarly, there is little variation in the content, structuring and curriculum of MBSR courses around the world.

Mindfulness has been oversold and commodified, reduced to a technique for just about any instrumental purpose. It can give inner-city kids a calming time-out, or hedge-fund traders a mental edge, or reduce the stress of military drone pilots. Void of a moral compass or ethical commitments, unmoored from a vision of the social good, the commodification of mindfulness keeps it anchored in the ethos of the market.

This has come about partly because proponents of mindfulness believe that the practice is apolitical, and so the avoidance of moral inquiry and the reluctance to consider a vision of the social good are intertwined. It is simply assumed that ethical behaviour will arise “naturally” from practice and the teacher’s “embodiment” of soft-spoken niceness, or through the happenstance of self-discovery. However, the claim that major ethical changes will follow from “paying attention to the present moment, non-judgmentally” is patently flawed. The emphasis on “non-judgmental awareness” can just as easily disable one’s moral intelligence.

In Selling Spirituality: The Silent Takeover of Religion, Jeremy Carrette and Richard King argue that traditions of Asian wisdom have been subject to colonisation and commodification since the 18th century, producing a highly individualistic spirituality, perfectly accommodated to dominant cultural values and requiring no substantive change in lifestyle. Such an individualistic spirituality is clearly linked with the neoliberal agenda of privatisation, especially when masked by the ambiguous language used in mindfulness. Market forces are already exploiting the momentum of the mindfulness movement, reorienting its goals to a highly circumscribed individual realm.

Mindfulness is easily co-opted and reduced to merely “pacifying feelings of anxiety and disquiet at the individual level, rather than seeking to challenge the social, political and economic inequalities that cause such distress”, write Carrette and King. But a commitment to this kind of privatised and psychologised mindfulness is political – therapeutically optimising individuals to make them “mentally fit”, attentive and resilient, so they may keep functioning within the system. Such capitulation seems like the farthest thing from a revolution – more like a quietist surrender.

Mindfulness is positioned as a force that can help us cope with the noxious influences of capitalism. But because what it offers is so easily assimilated by the market, its potential for social and political transformation is neutered. Leaders in the mindfulness movement believe that capitalism and spirituality can be reconciled; they want to relieve the stress of individuals without having to look deeper and more broadly at its causes.

Mindfulness is being sold to executives as a way to de-stress, focus and bounce back from working 80-hour weeks

A truly revolutionary mindfulness would challenge the western sense of entitlement to happiness irrespective of ethical conduct. However, mindfulness programmes do not ask executives to examine how their managerial decisions and corporate policies have institutionalised greed, ill will and delusion. Instead, the practice is being sold to executives as a way to de-stress, improve productivity and focus, and bounce back from working 80-hour weeks. They may well be “meditating”, but it works like taking an aspirin for a headache. Once the pain goes away, it is business as usual. Even if individuals become nicer people, the corporate agenda of maximising profits does not change.

If mindfulness just helps people cope with the toxic conditions that make them stressed in the first place, then perhaps we could aim a bit higher. Should we celebrate the fact that this perversion is helping people to “auto-exploit” themselves? This is the core of the problem. The internalisation of focus for mindfulness practice also leads to other things being internalised, from corporate requirements to structures of dominance in society. Perhaps worst of all, this submissive position is framed as freedom. Indeed, mindfulness thrives on doublespeak about freedom, celebrating self-centered “freedoms” while paying no attention to civic responsibility, or the cultivation of a collective mindfulness that finds genuine freedom within a co-operative and just society.

Of course, reductions in stress and increases in personal happiness and wellbeing are much easier to sell than serious questions about injustice, inequity and environmental devastation. The latter involve a challenge to the social order, while the former play directly to mindfulness’s priorities – sharpening people’s focus, improving their performance at work and in exams, and even promising better sex lives. Not only has mindfulness been repackaged as a novel technique of psychotherapy, but its utility is commercially marketed as self-help. This branding reinforces the notion that spiritual practices are indeed an individual’s private concern. And once privatised, these practices are easily co-opted for social, economic and political control.

Rather than being used as a means to awaken individuals and organisations to the unwholesome roots of greed, ill will and delusion, mindfulness is more often refashioned into a banal, therapeutic, self-help technique that can actually reinforce those roots.

Mindfulness is said to be a $4bn industry. More than 60,000 books for sale on Amazon have a variant of “mindfulness” in their title, touting the benefits of Mindful Parenting, Mindful Eating, Mindful Teaching, Mindful Therapy, Mindful Leadership, Mindful Finance, a Mindful Nation, and Mindful Dog Owners, to name just a few. There is also The Mindfulness Colouring Book, part of a bestselling subgenre in itself. Besides books, there are workshops, online courses, glossy magazines, documentary films, smartphone apps, bells, cushions, bracelets, beauty products and other paraphernalia, as well as a lucrative and burgeoning conference circuit. Mindfulness programmes have made their way into schools, Wall Street and Silicon Valley corporations, law firms, and government agencies, including the US military.

The presentation of mindfulness as a market-friendly palliative explains its warm reception in popular culture. It slots so neatly into the mindset of the workplace that its only real threat to the status quo is to offer people ways to become more skilful at the rat race. Modern society’s neoliberal consensus argues that those who enjoy power and wealth should be given free rein to accumulate more. It’s perhaps no surprise that those mindfulness merchants who accept market logic are a hit with the CEOs in Davos, where Kabat-Zinn has no qualms about preaching the gospel of competitive advantage from meditative practice.

Over the past few decades, neoliberalism has outgrown its conservative roots. It has hijacked public discourse to the extent that even self-professed progressives, such as Kabat-Zinn, think in neoliberal terms. Market values have invaded every corner of human life, defining how most of us are forced to interpret and live in the world.

Perhaps the most straightforward definition of neoliberalism comes from the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, who calls it “a programme for destroying collective structures that may impede the pure market logic”. We are generally conditioned to think that a market-based society provides us with ample (if not equal) opportunities for increasing the value of our “human capital” and self-worth. And in order to fully actualise personal freedom and potential, we need to maximise our own welfare, freedom, and happiness by deftly managing internal resources.

Since competition is so central, neoliberal ideology holds that all decisions about how society is run should be left to the workings of the marketplace, the most efficient mechanism for allowing competitors to maximise their own good. Other social actors – including the state, voluntary associations, and the like – are just obstacles to the smooth operation of market logic.

For an actor in neoliberal society, mindfulness is a skill to be cultivated, or a resource to be put to use. When mastered, it helps you to navigate the capitalist ocean’s tricky currents, keeping your attention “present-centred and non-judgmental” to deal with the inevitable stress and anxiety from competition. Mindfulness helps you to maximise your personal wellbeing.

All of this may help you to sleep better at night. But the consequences for society are potentially dire. The Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek has analysed this trend. As he sees it, mindfulness is “establishing itself as the hegemonic ideology of global capitalism”, by helping people “to fully participate in the capitalist dynamic while retaining the appearance of mental sanity”.

By deflecting attention from the social structures and material conditions in a capitalist culture, mindfulness is easily co-opted. Celebrity role models bless and endorse it, while Californian companies including Google, Facebook, Twitter, Apple and Zynga have embraced it as an adjunct to their brand. Google’s former in-house mindfulness tsar Chade-Meng Tan had the actual job title Jolly Good Fellow. “Search inside yourself,” he counselled colleagues and readers – for there, not in corporate culture – lies the source of your problems.

The rhetoric of “self-mastery”, “resilience” and “happiness” assumes wellbeing is simply a matter of developing a skill. Mindfulness cheerleaders are particularly fond of this trope, saying we can train our brains to be happy, like exercising muscles. Happiness, freedom and wellbeing become the products of individual effort. Such so-called “skills” can be developed without reliance on external factors, relationships or social conditions. Underneath its therapeutic discourse, mindfulness subtly reframes problems as the outcomes of choices. Personal troubles are never attributed to political or socioeconomic conditions, but are always psychological in nature and diagnosed as pathologies. Society therefore needs therapy, not radical change. This is perhaps why mindfulness initiatives have become so attractive to government policymakers. Societal problems rooted in inequality, racism, poverty, addiction and deteriorating mental health can be reframed in terms of individual psychology, requiring therapeutic help. Vulnerable subjects can even be told to provide this themselves.

Neoliberalism divides the world into winners and losers. It accomplishes this task through its ideological linchpin: the individualisation of all social phenomena. Since the autonomous (and free) individual is the primary focal point for society, social change is achieved not through political protest, organising and collective action, but via the free market and atomised actions of individuals. Any effort to change this through collective structures is generally troublesome to the neoliberal order. It is therefore discouraged.

An illustrative example is the practice of recycling. The real problem is the mass production of plastics by corporations, and their overuse in retail. However, consumers are led to believe that being personally wasteful is the underlying issue, which can be fixed if they change their habits. As a recent essay in Scientific American scoffs: “Recycling plastic is to saving the Earth what hammering a nail is to halting a falling skyscraper.” Yet the neoliberal doctrine of individual responsibility has performed its sleight-of-hand, distracting us from the real culprit. This is far from new. In the 1950s, the “Keep America Beautiful” campaign urged individuals to pick up their trash. The project was bankrolled by corporations such as Coca-Cola, Anheuser-Busch and Phillip Morris, in partnership with the public service announcement Ad Council, which coined the term “litterbug” to shame miscreants. Two decades later, a famous TV ad featured a Native American man weeping at the sight of a motorist dumping garbage. “People Start Pollution. People Can Stop It,” was the slogan. The essay in Scientific American, by Matt Wilkins, sees through such charades.

To change the world, we are told to work on ourselves – to change our minds by being more accepting of circumstances

We are repeatedly sold the same message: that individual action is the only real way to solve social problems, so we should take responsibility. We are trapped in a neoliberal trance by what the education scholar Henry Giroux calls a “disimagination machine”, because it stifles critical and radical thinking. We are admonished to look inward, and to manage ourselves. Disimagination impels us to abandon creative ideas about new possibilities. Instead of seeking to dismantle capitalism, or rein in its excesses, we should accept its demands and use self-discipline to be more effective in the market. To change the world, we are told to work on ourselves — to change our minds by being more mindful, nonjudgmental, and accepting of circumstances.

It is a fundamental tenet of neoliberal mindfulness, that the source of people’s problems is found in their heads. This has been accentuated by the pathologising and medicalisation of stress, which then requires a remedy and expert treatment – in the form of mindfulness interventions. The ideological message is that if you cannot alter the circumstances causing distress, you can change your reactions to your circumstances. In some ways, this can be helpful, since many things are not in our control. But to abandon all efforts to fix them seems excessive. Mindfulness practices do not permit critique or debate of what might be unjust, culturally toxic or environmentally destructive. Rather, the mindful imperative to “accept things as they are” while practising “nonjudgmental, present moment awareness” acts as a social anesthesia, preserving the status quo.

The mindfulness movement’s promise of “human flourishing” (which is also the rallying cry of positive psychology) is the closest it comes to defining a vision of social change. However, this vision remains individualised and depends on the personal choice to be more mindful. Mindfulness practitioners may of course have a very different political agenda to that of neoliberalism, but the risk is that they start to retreat into their own private worlds and particular identities — which is just where the neoliberal power structures want them.

Mindfulness practice is embedded in what Jennifer Silva calls the “mood economy”. In Coming Up Short: Working-Class Adulthood in an Age of Uncertainty, Silva explains that, like the privatisation of risk, a mood economy makes “individuals solely responsible for their emotional fates”. In such a political economy of affect, emotions are regulated as a means to enhance one’s “emotional capital”. At Google’s Search Inside Yourself mindfulness programme, emotional intelligence (EI) figures prominently in the curriculum. The programme is marketed to Google engineers as instrumental to their career success — by engaging in mindfulness practice, managing emotions generates surplus economic value, equivalent to the acquisition of capital. The mood economy also demands the ability to bounce back from setbacks to stay productive in a precarious economic context. Like positive psychology, the mindfulness movement has merged with the “science of happiness”. Once packaged in this way, it can be sold as a technique for personal life-hacking optimisation, disembedding individuals from social worlds.

From inboxing to thought showers: how business bullshit took over

All the promises of mindfulness resonate with what the University of Chicago cultural theorist Lauren Berlant calls “cruel optimism”, a defining neoliberal characteristic. It is cruel in that one makes affective investments in what amount to fantasies. We are told that if we practice mindfulness, and get our individual lives in order, we can be happy and secure. It is therefore implied that stable employment, home ownership, social mobility, career success and equality will naturally follow. We are also promised that we can gain self-mastery, controlling our minds and emotions so we can thrive and flourish amid the vagaries of capitalism.As Joshua Eisen, the author of Mindful Calculations, puts it: “Like kale, acai berries, gym memberships, vitamin water, and other new year’s resolutions, mindfulness indexes a profound desire to change, but one premised on a fundamental reassertion of neoliberal fantasies of self-control and unfettered agency.” We just have to sit in silence, watching our breath, and wait. It is doubly cruel because these normative fantasies of the “good life” are already crumbling under neoliberalism, and we make it worse if we focus individually on our feelings. Neglecting shared vulnerabilities and interdependence, we disimagine the collective ways we might protect ourselves. And despite the emptiness of nurturing fantasies, we continue to cling to them.

Mindfulness isn’t cruel in and of itself. It’s only cruel when fetishised and attached to inflated promises. It is then, as Berlant points out, that “the object that draws your attachment actively impedes the aim that brought you to it initially”. The cruelty lies in supporting the status quo while using the language of transformation. This is how neoliberal mindfulness promotes an individualistic vision of human flourishing, enticing us to accept things as they are, mindfully enduring the ravages of capitalism.

Thursday, 2 May 2019

The mess in India’s higher judiciary is, sadly, of its own making

Most of today’s judges on the Supreme Court bench were in their thirties on 7 May 1997 when, famously, the full court sat and issued a 16-point declaration called Restatement of Values of Judicial Life. That year was the 50th anniversary of our Independence. You can find the full text here.

Twenty years on, we should check if our most hallowed institution has lived up to it.

You might begin with the question: Why is it that the Supreme Court of India has been making headlines for controversies than for good news? The current Chief Justice of India, Ranjan Gogoi, as his two immediate predecessors, Justices Dipak Misra and J.S. Khehar, have faced crippling controversies. The two before them cadged convenient sarkari sinecures. One of these, regrettably, in a Raj Bhavan.

Khehar was “mentioned” in the diaries of dead Arunachal chief minister Kalikho Pul. Dipak Misra first faced an unprecedented joint press conference by his four senior-most colleagues, protesting what they saw as his high-handedness and lack of institutional democracy, and then an impeachment threat by the opposition. The ‘sexual harassment’ crisis facing Justice Gogoi now is the gravest.

Let’s presume that each of these was spotless and targeted by interested parties. But we simply cannot defend none of them facing any scrutiny. Mostly, it happened because there was no procedure, mechanism or institution for such an inquiry. And where there is one, the Internal Complaints Committee for Sexual Harassment under the Vishakha Guidelines laid down by the highest court, the matter has been referred to a specially constituted committee of SC judges first, which the complainant has rejected.

Here are the three key reasons our judiciary has dug itself into a deep hole. First, its insistence on ducking inconvenient questions by invoking stature and reputation. This means there’s never closure on any issue. Second, that while the court lectures us on transparency, it remains India’s most opaque institution. And third, there is no mechanism, even a council of respected elders, which could step in when a crisis of credibility or internal distrust became evident.

Parliament had tried to create the National Judicial Accountability Commission exactly for such situations, but the court struck it down 4-1 as unconstitutional. Three of the judges who served on that bench (including Chelameswar, the lone dissenter) figured in the four-judge press conference in Gogoi’s company.

Since Gogoi was the most senior among the four and the only one still in the chair, he needs to reflect on how his institution ended up here. Why is his Supreme Court looking like a big, flailing body oozing blood from a dozen, mostly self-inflicted cuts? And piranhas of various kinds are lurking.

It’s a tragedy when Supreme Court judges complain that they are victims of conspiracies. How did this most powerful institution, which is supposed to protect us and give us justice, become so vulnerable that busybody conspirators can threaten it? If it is so weak, where will we citizens go for justice?

The CJI’s office is a most exalted one. It is also possible that, as he and his brother judges in that most avoidable Saturday morning outburst indicated, there indeed is a conspiracy to undermine him. The Chief Justice of India deserves the fullest protection against interested parties throwing muck at him. But exactly the same principle should also apply to the complainant and the underdog.

Justice Gogoi and colleagues erred gravely in holding that peremptory Saturday morning sitting and pre-judging her case. Subsequent repairwork is now lost in the thickening murkiness, with an activist lawyer popping up with conspiracy theories. What these precisely are, we don’t know, because he has submitted them in a sealed cover.

The sealed cover has now become a defining metaphor for the last of the three big mistakes the court has made: Making itself the most opaque institution while preaching transparency from the Republic’s highest pulpit. Here is an indicative list. In the Rafale case, the government’s evidence is in a sealed envelope, as indeed are all the reports of the officer in-charge of the NRC process in Assam. In former CBI chief Alok Verma’s case the CVC report remains in a sealed cover, as do NIA’s reports in the Hadiya ‘conversion’ case.

The SC order to political parties to submit details of their donors to the EC is the latest example of this quaint judicial doctrine of the sealed cover. You might understand need for secrecy in a rare case. But if even the compensation for the assorted retirees heading the court-appointed Committee of Administrators of Indian cricket remains in a sealed cover for three years, it’s fair to ask why the court should be hiding behind secrecy when its entire BCCI excursion was about transparency.

Opacity is comforting. You can so easily get used to it. The SC protects RTI for us, but claims immunity for itself. Only seven of 27 SC judges have disclosed their assets. There is no transparency or disclosure of the collegium proceedings, or even explanation when it changes its mind on an appointment. Shouldn’t you have the right to know exactly how many special and empowered committees the court has set up, mostly as a result of PILs, their members—especially retirees—and compensations? If the executive hid such information from you, you’d go to the courts. Where do you go against the Supreme Court?

Judges are wise people. It follows that top judges should be among the wisest of all. They must reflect on the consequences of their making the judiciary an insulated and cocooned institution while being the supreme force for transparency and disclosure elsewhere. It is this contradiction and hypocrisy that the complainant against the CJI has laid bare. That’s why the court is looking unsure.

Read that 16th and last point in that 1997 Restatement of Values of Judicial Life: ‘Every judge must at all times be conscious that he is under the public gaze and there should be no act or omission by him which is unbecoming of the high office he occupies and the public esteem in which that office is held.’

The Supreme Court’s refuge in opacity does not live up to this principle. An institutional reset and retreat are called for here. Of course, while both the complainant and the CJI get justice.

Why we are addicted to conspiracy theories

In January 2015, I spent the longest, queasiest week of my life on a cruise ship filled with conspiracy theorists. As our boat rattled toward Mexico and back, I heard about every wild plot, secret plan and dark cover-up imaginable. It was mostly fascinating, occasionally exasperating and the cause of a headache that took months to fade. To my pleasant surprise, given that I was a reporter travelling among a group of deeply suspicious people, I was accused of working for the CIA only once.

The unshakeable certainty possessed by many of the conspiracy theorists sometimes made me want to tear my hair out, how tightly they clung to the strangest and most far-fetched ideas. I was pretty sure they had lost their hold on reality as a result of being permanently and immovably on the fringes of American life. I felt bad for them and, to be honest, a little superior.

“The things that everyone thinks are crazy now, the mainstream will pick up on them,” proclaimed Sean David Morton early in the trip. “Twenty sixteen is going to be one of those pivotal years, not just in human history, but in American history as well.”

Morton is a self-proclaimed psychic and UFO expert, and someone who has made a lot of dubious claims about how to beat government agencies such as the IRS in court. (In 2017, he was sentenced to six years in prison for tax fraud.) I dismissed his predictions about 2016 the way I dismissed a lot of his prophecies and basic insistence about how the world works. Morton and the other conspiracy theorists on the boat were confident of a whole lot of things I found unbelievable, but which have plenty of adherents in the US and abroad.

Some of them asserted that mass shootings such as Sandy Hook are staged by the US government with the help of “crisis actors” as part of a sinister (and evidently delayed) gun-grab. The moon landing was obviously fake (that one didn’t even merit much discussion). The government was covering up not just the link between vaccines and autism but also the cures for cancer and Aids. Everywhere they looked, there was a hidden plot, a secret cabal and, as the gospel of Matthew teaches about salvation, only a narrow gate that leads to the truth.

I chronicled my stressful, occasionally hilarious, unexpectedly enlightening experience onboard the Conspira-Sea Cruise as a reporter for the feminist website Jezebel, and then I tried to forget about it. I had done a kooky trip on a boat, the kind of stunt journalism project every feature writer loves, and it was over. Conspiracy theorists, after all, were a sideshow.

But I began to notice that they were increasingly encroaching on my usual beats, such as politics. In July 2016, I was walking down a clogged, chaotic narrow street in Cleveland, Ohio, where thousands of reporters, pundits, politicians and Donald Trump fans had amassed to attend the Republican national convention. I was there as a reporter and was busy taking pictures of particularly sexist anti-Hillary Clinton merchandise. There was a lot of it around, for sale on the street and proudly displayed on people’s bodies: from TRUMP THAT BITCH badges to white T-shirts reading HILLARY SUCKS, BUT NOT LIKE MONICA.

Some of the attendees were from InfoWars, the mega-empire of suspicion – a radio show, website and vastly profitable store of lifestyle products – founded by Austin, Texas-based host Alex Jones. For many years, Jones was a harmless, nutty radio shock-jock: a guy shouting into a microphone, warning that the government was trying to make everyone gay through covert chemical warfare, by releasing homosexuality agents into the water supply. (“They’re turning the freaking frogs gay!” he famously shouted.)

President Barack Obama, subject of a number of conspiracy theories, not least that he was born in Kenya. Photograph: Jim Watson/AFP/Getty

Jones also made less adorably kooky claims: that a number of mass shootings and acts of terrorism, such as the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, were faked by the government; that the CEO of Chobani, the yogurt company, was busy importing “migrant rapists” to work at its Idaho plant; that Hillary Clinton is an actual demon who smells of sulphur, hails from Hell itself and has “personally murdered and chopped up and raped” little children.

Jones and Donald Trump were longtime mutual fans. After announcing his run, candidate Trump made one of his first media appearances on Jones’s show, appearing via Skype from Trump Tower. Jones endorsed him early and often and, in turn, many of the radio host’s favourite talking points turned up in Trump’s speeches. Jones began darkly predicting that the elections would be “rigged” in Clinton’s favour, a claim that Trump quickly made a central tenet of the latter days of his campaign. At the end of September, Jones began predicting that Clinton would be on performance-enhancing drugs of some kind during the presidential debates; by October, Trump was implying that, too, and demanding that Clinton be drug-tested.

Soon after, the US narrowly elected a conspiracy enthusiast as its president, a man who wrongly believes that vaccines cause autism, that global warming is a hoax perpetuated by the Chinese “in order to make US manufacturing non-competitive,” as he tweeted in 2012, and who claimed, for attention and political gain, that Barack Obama was born in Kenya. One of the first people the president-elect called after his thunderous upset victory was Jones. Then, in a very short time, some of the most wild-eyed conspiracy-mongers in the country were influencing federal policy and taking meetings at the White House.

Here’s the thing: the conspiracy theorists aboard the cruise and in the streets of Cleveland could have warned me that Trump’s election was coming, had I only been willing to listen.

Many of the hardcore conspiracy theorists I sailed with on the Conspira-Sea Cruise weren’t very engaged in politics, given that they believe it’s a fake system designed to give us the illusion of control by our real overlords – the Illuminati, the international bankers or perhaps the giant lizard people. But when they did consider the subject, they loved Trump, even the left-leaning among them who might have once preferred Bernie Sanders.

They recognised the future president as a “truth-teller” in a style that spoke to them and many other Americans. They liked his thoughts about a rigged system and a government working against them, the way it spoke to what they had always believed, and the neat way he was able to peg the enemy with soundbites: the “lying media”, “crooked Hillary”, the bottomless abyss of the Washington “swamp”. They were confident of his victory – if the globalists and the new world order didn’t get in the way, and they certainly would try. Just as Morton said, they were sure that 2016 was going to change everything.

Trump’s fondness for conspiracy continued apace into his presidency: his Twitter account became a megaphone for every dark suspicion he has about the biased media and the rigged government working against him. At one particularly low point he even went so far as to accuse his political opponents of inflating the number of deaths in Puerto Rico caused by Hurricane Maria. His supporters became consumed by the concept of the “deep state”, seized by a conviction that a shadow regime is working hard to undermine the White House. At the same time, Trump brought a raft of conspiracy theorists into his cabinet: among them was secretary of housing and urban development Ben Carson, who suggested that President Obama would declare martial lawand cancel the 2016 elections to remain in power. There was also National Security adviser Michael Flynn (who was quickly fired), notorious for retweeting stories linking Hillary Clinton to child sex trafficking.

With the candidacy and then election of a conspiracy pedlar, conspiratorial thinking leaked from its traditional confines to spread in new, more visible ways across the country. As a result, a fresh wave of conspiracy theories and an obsession with their negative effects engulfed the US. We all worried late in the election season about “fake news”, a term for disinformation that quickly lost all meaning as it was gleefully seized on by the Trump administration to describe any media attention they didn’t like. We fixated on a conspiracy theorist taking the White House, and then we fretted over whether he was a true believer or just a cynical opportunist. And as left-leaning people found themselves unrepresented in government, with the judicial, executive and legislative branches held by the right, they too started to engage more in conspiracy theorising.

The reality is that the US has been a nation gripped by conspiracy for a long time. The Kennedy assassination has been hotly debated for years. The feminist and antiwar movements of the 1960s were, for a time, believed by a not-inconsiderable number of Americans to be part of a communist plot to weaken the country. A majority have believed for decades that the government is hiding what it knows about extraterrestrials. Since the early 1990s, suspicions that the Clintons were running a drug cartel and/or having their enemies murdered were a persistent part of the discourse on the right. And the website WorldNetDaily was pushing birther theories and talk of death panels (the idea, first articulated by Sarah Palin in 2009, that under Obamacare bureaucrats would decide whether the elderly deserved medical care) long before “fake news” became a talking point. Many black Americans have, for years, believed that the CIA flooded poor neighborhoods with drugs such as crack in order to destroy them.

The Trump era has merely focused our attention back on to something that has reappeared with reliable persistence: the conspiratorial thinking and dark suspicions that have never fully left us. Conspiracy theorising has been part of the American system of governance and culture and thought since its beginnings: as the journalist Jesse Walker writes in his book The United States of Paranoia, early white settlers, including history textbook favourite Cotton Mather, openly speculated that Native Americans were controlled by the devil, and conspiring with him and a horde of related demons to drive them out. Walker also points to the work of the historian Jeffrey Pasley, who found what he called the “myth of the superchief”: the colonist idea that every Native-led resistance or attack was directed by an “Indian mastermind or monarch in control of tens of thousands of warriors”.

The elements of suspicion were present long before the 2016 election, quietly shaping the way large numbers of people see the government, the media and the nature of what’s true and trustworthy.

And for all of our bogus suspicions, there are those that have been given credence by the government itself. We have seen a sizeable number of real conspiracies revealed over the past half century, from Watergate to recently declassified evidence of secret CIA programmes, to the fact that elements within the Russian government really did conspire to interfere with US elections. There is a perpetual tug between conspiracy theorists and actual conspiracies, between things that are genuinely not believable and truths that are so outlandish they can be hard, at first, to believe.

But while conspiracy theories are as old as the US itself, there is something new at work: people who peddle lies and half-truths have come to prominence, fame and power as never before. If the conspiratorial world is a vast ocean, 2016 was clearly the year that Alex Jones – along with other groups, such as anti-immigration extremists, anti-Muslim thinktanks and open neo-Nazis and white supremacists – were able to catch the wave of the Trump presidency and surf to the mainstream shore.

Over and over, I found that the people involved in conspiracy communities weren’t necessarily some mysterious “other”. We are all prone to believing half-truths, forming connections where there are none to be found, or finding importance in political and social events that may not have much significance at all.

I was interested in understanding why this new surge of conspiracism has appeared, knowing that historically, times of tumult and social upheaval tend to lead to a parallel surge in conspiracy thinking. I found some of my answer in our increasingly rigid class structure, one that leaves many people feeling locked into their circumstances and desperate to find someone to blame. I found it in rising disenfranchisement, a feeling many people have that they are shut out of systems of power, pounding furiously at iron doors that will never open to admit them. I found it in the frustratingly opaque US healthcare system, a vanishing social safety net, a political environment that seizes cynically on a renewed distrust of the news media.

Together, these elements helped create a society in which many Americans see millions of snares, laid by a menacing group of enemies, all the more alarming for how difficult they are to identify and pin down.

Let’s pause to attempt to define a conspiracy theory. It is a belief that a small group of people are working in secret against the common good, to create harm, to effect some negative change in society, to seize power for themselves, or to hide some deadly or consequential secret. An actual conspiracy is when a small group of people are working in secret against the common good – and anyone who tells you we can always easily distinguish fictitious plots from real ones probably hasn’t read much history.

Conspiracy theories tend to flourish especially at times of rapid social change, when we are re-evaluating ourselves and, perhaps, facing uncomfortable questions in the process. In 1980, the civil liberties lawyer and author Frank Donner wrote that conspiracism reveals a fundamental insecurity about who Americans want to be versus who they are.

“Especially in times of stress, exaggerated febrile explanations of unwelcome reality come to the surface of American life and attract support,” he wrote. The continual resurgence of conspiracy movements, he claimed, “illuminate[s] a striking contrast between our claims to superiority, indeed our mission as a redeemer nation to bring a new world order, and the extraordinary fragility of our confidence in our institutions”. That contrast, he said, “has led some observers to conclude that we are, subconsciously, quite insecure about the value and permanence of our society”.

In the past few years, medical conspiracies have undergone a resurgence like few other alternative beliefs, and they have a unique power to do harm. Anti-vaccine activists have had a direct hand in creating serious outbreaks of the measles, which they have then argued are hoaxes ginned up by the government to sell more vaccines. There is also evidence that this form of suspicion is being manipulated by malicious outside actors. A 2018 study by researchers at George Washington University found evidence that Russian bot accounts that had been dedicated to sowing various kinds of division during the 2016 election were, two years later, tweeting both pro- and anti-vaccine content, seeking to widen and exploit that divide, too.

Medical conspiracy theories are big, profitable business: an uptick in the belief that the government is hiding a cure for cancer has led people back to buying laetrile, a discredited fake drug popular in the 1970s. Fake medicines for cancer and other grave diseases are peddled by players of all sizes, from large importers to individual retailers. People such as Alex Jones – but not just him – are making multimillion-dollar sales in supplements and quack cures.

At the same time, medical conspiracies aren’t irrational. They are based on frustration with what is seen as the opacity of the medical and pharmaceutical systems. They have taken root in the US, a country with profoundly expensive and dysfunctional healthcare – some adherents take untested cures because they can’t afford the real thing. And there is a long history around the world of doctors giving their approval to innovations – cigarettes, certain levels of radiation, thalidomide, mercury – that turn out to be anything but safe.

Medical conspiracy theories are startlingly widespread. In a study published in 2014, University of Chicago political scientists Eric Oliver and Thomas Wood surveyed 1,351 American adults and found that 37% believe the US Food and Drug Administration is “intentionally suppressing natural cures for cancer because of drug company pressure”.

Meanwhile, 20% agreed that corporations are preventing public health officials from releasing data linking mobile phones to cancer, and another 20% that doctors still want to vaccinate children “even though they know such vaccines to be dangerous”. (Though the study didn’t get into this, many people who feel that way assume doctors do it because they’re in the pockets of Big Vaccine, although vaccines are actually less profitable than many other kinds of medical procedures.)

Subscribing to those conspiracy theories is linked to specific health behaviours: believers are less likely to get flu jabs or wear sunscreen and more likely to seek alternative treatments. (In a more harmless vein, they are also more likely to buy organic vegetables and avoid GMOs.) They are also less inclined to consult a family doctor, relying instead on friends, family, the internet or celebrity doctors for health advice.

The anti-vaccine movement is the most successful medical conspiracy – persistent, lucrative and perpetually able to net new believers in spite of scientific evidence. It is also emblematic of all such conspiracy theories: people get caught up in them through either grief or desperation, exacerbated by the absence of hard answers and suspicion about whether a large and often coldly impersonal medical system is looking out for their best interests. And an army of hucksters stands ready to catch them and make a buck.

The king of dubious health claims is Alex Jones, whose InfoWars Life Health Store sells a variety of questionable supplements. Most of Jones’s products come from a Houston-based company called the Global Healing Center and are relabelled with the InfoWars logo. Global Healing Center’s CEO, Dr Edward Group, is also Jones’s go-to health expert, regularly appearing on the programme to opine about vaccines (he thinks they are bad) and fungus (the root of all evil – luckily, one of the supplements that Jones and Group sell helps banish it from the body).

Group isn’t a medical doctor but a chiropractor, although his website claims a string of other credentials, such as degrees from MIT and Harvard, where he attended continuing education programmes that are virtually impossible to fail provided you pay the bill on time. Until a few years ago, Group also claimed to have a medical degree from the Joseph LaFortune School of Medicine. The LaFortune School is based in Haiti and is not accredited. That one is no longer on his CV.

Several disgruntled Global Healing Center staff members spoke to me for a 2017 story about Group and Jones’s relationship, claiming that the company earns millions a year while toeing an extremely fine line in making claims for its products. “Global Healing Center pretends to care about FDA and FTC regulation, but at the end of the day, GHC says a lot of things that are “incorrect, totally circumstantial or based on incomplete evidence,” one employee said.

Nowhere is that clearer than in the claims that Jones and Group make about colloidal silver, which Jones sells as Silver Bullet. Colloidal silver is a popular new-age health product, touted as a miraculous antibacterial and antimicrobial agent that is dabbed on the skin. But Group and Jones advocate drinking the stuff. In 2014, Group told the InfoWars audience that he has been doing so for years. “I’ve drank half a gallon of silver, done a 10 parts per million silver, for probably 10 or 15 days,” Group said reassuringly.

Group also claims that the FDA “raided” his office to steal his colloidal silver, because it is too powerful. “It was one of the things that was targeted by the FDA because it was a threat to the pharmaceutical companies and a threat for doctor’s visits because it worked so good in the body.”

Colloidal silver doesn’t, in fact, work so good in the body; you are not supposed to put it there. The Mayo Clinic says silver has “no known purpose in the body” and drinking colloidal silver can cause argyria, a condition that can permanently turn skin, eyes and internal organs an ashen bluish color. (Jones and Group acknowledge on InfoWars that this can happen, but only when people are using silver incorrectly.) Jones and their ilk complain that they are under attack by the media, the government and some shadowy third entities for telling truths too powerful to ignore.

Unusually, medical conspiracy thinking is not solely the province of the far right or the libertarian bluish-from-too-much-silver fringe. The bourgeois hippie left participates, too. The website Quartz published an astonishing story showing that many of the products sold by Jones are identical to thosepeddled by Goop, Gwyneth Paltrow’s new-age lifestyle website. And there’s David “Avocado” Wolfe, another new-age lifestyle vlogger, who has called vaccine manufacturers “criminal and satanic” and said that chemtrails are real and toxic. (“Chemtrails” are actually contrails, or water vapour from airplanes, which people in the deep end of the conspiracy pool think are clouds of poison gas being showered on the populace to, once again, make us docile and weak.)