'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label cover-up. Show all posts

Showing posts with label cover-up. Show all posts

Saturday, 8 June 2024

Thursday, 1 June 2023

The backlash: how slavery research came under fire

More and more institutions are commissioning investigations into their historical links to slavery – but the fallout at one Cambridge college suggests these projects are meeting growing resistance writes Samira Shackle in The Guardian

When the historian Nicolas Bell-Romero started a job researching Cambridge University’s past links to transatlantic slavery three years ago, he did not expect to be pilloried in the national press by anonymous dons as “a ‘woke activist’ with an agenda”. Before his work was even published, it would spark a bitter conflict at the university – with accusations of bullying and censorship that were quickly picked up by rightwing papers as a warning about “fanatical” scholars tarnishing Britain’s history.

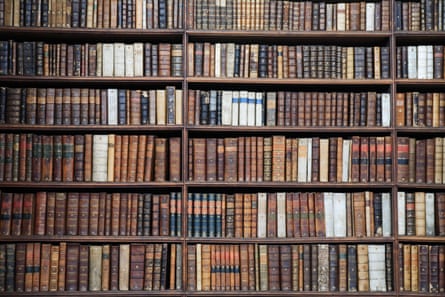

Bell-Romero, originally from Australia, had recently finished a PhD at Cambridge. He was at the start of his academic career and eager to prove himself. This was the ideal post-doctoral position: a chance to dig into the university’s archives to explore faculty and alumni links to slavery, and whether these links had translated into profit for Cambridge. It was the kind of work that, Bell-Romero said, “seems boring to the layperson” – spending days immersed in dusty archives and logbooks, exploring 18th- and 19th-century financial records. But as a historian, it was thrilling. It offered a chance to make a genuinely fresh contribution to burgeoning research about Britain’s relationship to slavery.

In the spring of 2020, Bell-Romero and another post-doctoral researcher, Sabine Cadeau, began work on the legacies of enslavement inquiry. Cadeau and Bell-Romero had a wide-ranging brief: to examine how the university gained from slavery, through specific financial bequests and gifts, but also to investigate how its scholarship might have reinforced, validated or challenged race-based thinking.

Cambridge was never a centre of industry like Manchester, Liverpool or Bristol, cities in which historic links to slavery are deep and obviously apparent – but as one of the oldest and wealthiest institutions in the country, the university makes an interesting case study for how intimately profits from slavery were entwined with British life. Given how many wealthy people in Britain in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries were slaveholders, or invested in the slave economy, it was a reasonable expectation that both faculty and alumni may have benefited financially, and that this may have translated into donations to the university.

In the past decade, universities in the UK and US have commissioned similar research. Top US universities such as Harvard and Georgetown found they had enslaved people and benefited from donations connected to slavery. The first major research effort in the UK, at the University of Glasgow, began in 2018, but soon similar projects launched at Bristol, Edinburgh, Oxford, Manchester and Nottingham. Stephen Mullen, co-author of the Glasgow report, told me that he was surprised not only by the extent of the university’s financial ties to slavery, but by how much that wealth is still funding these institutions.

In their report, Mullen and his co-author Simon Newman established a methodology for working out the difficult question of how the financial value of historic donations and investments might translate into modern money, which produces a range of estimates rather than a single number: in the case of Glasgow, between £16.7m and £198m. In response to the research, the University of Glasgow initiated a “reparative justice” programme, including a £20m partnership with the University of the West Indies and a new centre for slavery studies.

All of this marks a dramatic change in how Britain thinks about slavery, and especially the idea of reparations. For the most part, when Britain has engaged with this history, the tendency has been to focus on the successful campaign for abolition; historians of slavery like to repeat the famous quip that Britain invented the slave trade solely to abolish it.

This wider trend is reflected in Cambridge. As far as the story of slavery and the University of Cambridge goes, perhaps the most well-known fact is that some of Britain’s key abolitionists – William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson – were educated there. But British celebration of the abolition of slavery in the 1800s has tended to elide the awkward question of who the abolitionists were fighting against, and the point that the wealth and economic power generated by slavery did not disappear when the Abolition Act was passed.

“It was interesting to me that there weren’t so many questions about the other side – were slaveholders educated here? Did slaveholders give benefactions? Did students invest in the different slave-trading companies?” Bell-Romero said. “It’s not about smashing what came before, it’s about contributing and building on histories.”

Cambridge consists of the central university and 31 constituent colleges, each of which has its own administration, decision-making powers and budgets. Most of the university’s wealth is situated within colleges, and from the outset, the legacies of enslavement inquiry relied to an extent on colleges granting Bell-Romero and Cadeau access to their archives. This wasn’t always easy. “The entire research experience, even now, remains a constant struggle for archival access, an ongoing political tug of war,” Cadeau told me in late 2022. “There was financial support for the research from the central university, but mixed feelings and outright opposition were both widespread.”

The conflict at Caius seemed to be part of a wider faltering of legacies of slavery research – through overt backlash, or institutions announcing projects with great fanfare but not following through with support and funding. Hilary Beckles, the vice-chancellor of the University of the West Indies and the author of Britain’s Black Debt, calls this pattern “research and run” – where universities do the archival work, then say a quick sorry and run from the implications of the findings, leaving the researchers exposed.

The historian Olivette Otele, a scholar of slavery and historical memory who was the first Black woman to be appointed a professor of history in the UK, joined the University of Bristol in 2020, and worked on the university’s own research into its deep connections to the slave trade. When she left just two years later, a colleague in another department tweeted that the university had used Otele “as a human shield to deflect legitimate criticism”. Announcing her departure, Otele wrote on Twitter: “The workload became insane and not compensated by financial reward. I actually burnt out,” adding that colleagues had been “sabotaging my reputation inside and outside the uni.”

As far as anyone could see, Caius had backed away from publishing Bell-Romero’s report after the controversy; Everill, head of the working group, was not sure it would ever be published. But in July, a newspaper submitted a freedom of information request about it. (Newspapers increasingly submit FoIs about academic research on subjects like slavery and empire as universities have become the frontline in the culture war; a controversial Times front page in August claimed that universities were changing syllabuses, even though their own data did not bear this out. Riley recalled one absurd example, where a journalist sent an FoI requesting all emails from academics using the word “woke”. “There were none, because we don’t actually sit there writing ‘I’m a woke historian’. That is insane.”)

The following month, the Caius report was published online, with the proposal for MPhil funding removed. It was not covered anywhere. “Probably because it turns out that wasn’t actually that inflammatory,” Everill said. In a statement to the Guardian, the master of the college, Prof Pippa Rogerson, said: “The report makes uncomfortable reading for all those affiliated to Caius. The College is 675 years old and it is important we acknowledge our complex past.”

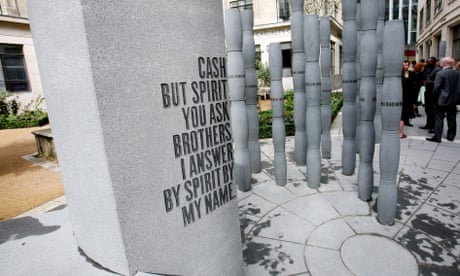

In September, Bell-Romero and Cadeau’s much larger Cambridge University legacies of enslavement project was published. It found that Cambridge fellows had been involved in the East India Company and other slave-trading entities, and that the university had directly invested in the South Sea Company. They wrote: “Such financial involvement both helped to facilitate the slave trade and brought very significant financial benefits to Cambridge.” The report was covered by major news outlets, but did not provoke a particularly strong response.

The conflict over the Caius research suggests that these disputes often have little to do with the archival research itself, or its conclusions. In the view of the critics, the research is discredited by its intention to correct past wrongs. Even when the researchers insist that they are not trying to assign blame or guilt, the critics insist in return – not without some justification – that whether or not this is the intention, it is almost always the effect. This is presumably why they disapprove of doing the research to begin with.

Seen this way, it is a standoff that has no hope of resolution. When I spoke to Abulafia, he questioned the point of the research: “Cambridge University and its role in slavery is not, to my mind, as big a question as all sorts of other questions one could argue about the slave trade,” he said. But scholars working on the area argue that this is precisely the point; to understand institutions’ relationships to slavery, whether small or large, and through this to build a fuller picture of the past. “When we do this research, we’re just adding another layer, another perspective,” said Bell-Romero. The critics, of course, see this empirical modesty as disingenuous. But the archival work carries on, all over the country, and the diametrically opposing views on the very premise will inevitably lead to more conflicts.

In late September, Cadeau and Bell-Romero organised an academic conference about reparations, held at the Møller Institute, a starkly modern building west of Cambridge city centre. A few days before, it was covered in the Telegraph, which quoted anonymous sources describing it as “propagandist” and “fanatical” and Abulafia saying: “It’s that sense that it’s going to be one-sided that concerns me.” Cadeau, who is now a lecturer of diaspora history at Soas in London, was unfazed. “What I am most concerned about are legacies of racism. I am concerned with how little this country knows about slavery, even leading historians,” she told me. “I have been more concerned about the implications of how we treat the history of slavery, and whether or not our societies will address the legacies of slavery and racism, and much less concerned about the press.”

In his opening remarks to the conference, the historian Prof Nicholas Guyatt acknowledged the negative coverage, saying: “We’ve had some media attention already and that’s great, I welcome all views and am pleased everyone is here to listen to our fantastic speakers.” Bell-Romero presented a paper on the profits of slavery at Oxbridge. Cadeau spoke about her research into South Sea Company annuities at Cambridge, saying that it was hard to find an older college in Cambridge that doesn’t have links to this funding. No news story about the conference emerged – perhaps because in practice this was a fairly routine academic exercise. People presented papers on their niche areas of research, ran over time and debated.

On the final day of the conference, I sat with Bell-Romero in the lunch hall. He told me that he felt the launch of the Cambridge project had been handled better than the Caius report; the draft had gone to expert readers and the university backed the research it had commissioned. While the academics waited for the next talk to begin, Bell-Romero and a few other scholars working on slavery and reparations discussed the growing backlash to their work in an incredulous and frustrated tone. One British academic said he receives death threats every time he speaks about the case for reparations. After a few minutes of weary commiseration, they stood up from their empty plates and walked back into the lecture theatre.

“If you take pride in the past,” a Latin American researcher said with quiet exasperation before leaving, “then you have to take responsibility, too.”

When the historian Nicolas Bell-Romero started a job researching Cambridge University’s past links to transatlantic slavery three years ago, he did not expect to be pilloried in the national press by anonymous dons as “a ‘woke activist’ with an agenda”. Before his work was even published, it would spark a bitter conflict at the university – with accusations of bullying and censorship that were quickly picked up by rightwing papers as a warning about “fanatical” scholars tarnishing Britain’s history.

Bell-Romero, originally from Australia, had recently finished a PhD at Cambridge. He was at the start of his academic career and eager to prove himself. This was the ideal post-doctoral position: a chance to dig into the university’s archives to explore faculty and alumni links to slavery, and whether these links had translated into profit for Cambridge. It was the kind of work that, Bell-Romero said, “seems boring to the layperson” – spending days immersed in dusty archives and logbooks, exploring 18th- and 19th-century financial records. But as a historian, it was thrilling. It offered a chance to make a genuinely fresh contribution to burgeoning research about Britain’s relationship to slavery.

In the spring of 2020, Bell-Romero and another post-doctoral researcher, Sabine Cadeau, began work on the legacies of enslavement inquiry. Cadeau and Bell-Romero had a wide-ranging brief: to examine how the university gained from slavery, through specific financial bequests and gifts, but also to investigate how its scholarship might have reinforced, validated or challenged race-based thinking.

Cambridge was never a centre of industry like Manchester, Liverpool or Bristol, cities in which historic links to slavery are deep and obviously apparent – but as one of the oldest and wealthiest institutions in the country, the university makes an interesting case study for how intimately profits from slavery were entwined with British life. Given how many wealthy people in Britain in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries were slaveholders, or invested in the slave economy, it was a reasonable expectation that both faculty and alumni may have benefited financially, and that this may have translated into donations to the university.

In the past decade, universities in the UK and US have commissioned similar research. Top US universities such as Harvard and Georgetown found they had enslaved people and benefited from donations connected to slavery. The first major research effort in the UK, at the University of Glasgow, began in 2018, but soon similar projects launched at Bristol, Edinburgh, Oxford, Manchester and Nottingham. Stephen Mullen, co-author of the Glasgow report, told me that he was surprised not only by the extent of the university’s financial ties to slavery, but by how much that wealth is still funding these institutions.

In their report, Mullen and his co-author Simon Newman established a methodology for working out the difficult question of how the financial value of historic donations and investments might translate into modern money, which produces a range of estimates rather than a single number: in the case of Glasgow, between £16.7m and £198m. In response to the research, the University of Glasgow initiated a “reparative justice” programme, including a £20m partnership with the University of the West Indies and a new centre for slavery studies.

All of this marks a dramatic change in how Britain thinks about slavery, and especially the idea of reparations. For the most part, when Britain has engaged with this history, the tendency has been to focus on the successful campaign for abolition; historians of slavery like to repeat the famous quip that Britain invented the slave trade solely to abolish it.

This wider trend is reflected in Cambridge. As far as the story of slavery and the University of Cambridge goes, perhaps the most well-known fact is that some of Britain’s key abolitionists – William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson – were educated there. But British celebration of the abolition of slavery in the 1800s has tended to elide the awkward question of who the abolitionists were fighting against, and the point that the wealth and economic power generated by slavery did not disappear when the Abolition Act was passed.

“It was interesting to me that there weren’t so many questions about the other side – were slaveholders educated here? Did slaveholders give benefactions? Did students invest in the different slave-trading companies?” Bell-Romero said. “It’s not about smashing what came before, it’s about contributing and building on histories.”

Cambridge consists of the central university and 31 constituent colleges, each of which has its own administration, decision-making powers and budgets. Most of the university’s wealth is situated within colleges, and from the outset, the legacies of enslavement inquiry relied to an extent on colleges granting Bell-Romero and Cadeau access to their archives. This wasn’t always easy. “The entire research experience, even now, remains a constant struggle for archival access, an ongoing political tug of war,” Cadeau told me in late 2022. “There was financial support for the research from the central university, but mixed feelings and outright opposition were both widespread.”

Gonville and Caius college (centre) at Cambridge University. Photograph: eye35/Alamy

So when Bell-Romero was approached by Gonville and Caius, the college where he had recently completed his PhD, to conduct a separate piece of research into the college’s links to slavery, he was delighted. Caius, as it is commonly known (it’s pronounced “Keys”), was founded in 1348. One of the oldest and wealthiest colleges in Cambridge, it is also seen as one of the most conservative and traditional. The college offered him a year’s contract, working one day a week, meaning he had about 50 days to do the archival research and write the report – a very short time for a broad brief.

As with the university inquiry, the idea was to look at all possible links to slavery. Alongside investigating whether the college held investments in slave-trading entities such as the East India, South Sea and Royal African Companies, he was asked to explore any connections to slavery among alumni, students and faculty. Not only would this be interesting in its own right, but hugely useful for the wider project. He said yes. “I just thought – this is wonderful, unrestricted access to the archive,” he said. “That’s a dream for a historian. It’s as good as it gets.”

But it was at Gonville and Caius that the problems would begin. The reaction to Bell-Romero’s draft report caused a rift among faculty at the college – with some pushing to prevent its publication entirely. According to the critics, the work suggested all white people “carry the taint of original sin” and that it was motivated by an “agenda” to “implicate” the college in slavery.

What happened at the college demonstrates the collision between two different worldviews: one that sees research into the history of slavery as a routine, but vital, academic exercise; and another that sees it as an overtly biased undertaking and a threat to the way historical knowledge is produced. The intensity of this clash sheds some light on why it has proved so difficult to reappraise Britain’s past.

When the Cambridge vice-chancellor Stephen Toope first announced the legacies of enslavement inquiry, he said he wanted the university to “acknowledge its role during that dark phase of human history”, adding: “We cannot change the past, but nor should we seek to hide from it.”

Momentum was building around institutions looking into their links to slavery. Historians working on this area see this as a valuable addition to historic knowledge and a way to understand how the profits of slavery shaped Britain. Many of the richest people in 18th- and 19th-century Britain were involved in the slave trade and the plantation economy. The trade and distribution of goods produced by enslaved people helped fuel Britain’s development.

While enslaved people were mostly overseas, in colonies, out of sight, slavery funded British wealth and institutions from the Bank of England to the Royal Mail. The extent to which modern Britain was shaped by the profits of the transatlantic slave economy was made even clearer with the launch in 2013 of the Legacies of British Slave-ownership project at University College London. It digitised the records of tens of thousands of people who claimed compensation from the government when colonial slavery was abolished in 1833, making it far easier to see how the wealth created by slavery spread throughout Britain after abolition. “Slave-ownership,” the researchers concluded, “permeated the British elites of the early 19th century and helped form the elites of the 20th century.” (Among others, it showed that David Cameron’s ancestors, and the founders of the Greene King pub chain, had enslaved people.)

But as Bell-Romero would write in his report on Caius, “the legacies of enslavement encompassed far more than the ownership of plantations and investments in the slave trade”. Scholars undertaking this kind of archival research typically look at the myriad ways in which individuals linked to an institution might have profited from slavery – ranging from direct involvement in the trade of enslaved people or the goods they produced, to one-step-removed financial interests such as holding shares in slave-trading entities such as the South Sea or East India Companies.

Bronwen Everill, an expert in the history of slavery and a fellow at Caius, points out “how widespread and mundane all of this was”. Mapping these connections, she says, simply “makes it much harder to hold the belief that Britain suddenly rose to power through its innate qualities; actually, this great wealth is linked to a very specific moment of wealth creation through the dramatic exploitation of African labour.”

This academic interest in forensically quantifying British institutions’ involvement in slavery has been steadily growing for several decades. But in recent years, this has been accompanied by calls for Britain to re-evaluate its imperial history, starting with the Rhodes Must Fall campaign in 2015. The Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 turbo-charged the debate, and in response, more institutions in the UK commissioned research on their historic links to slavery – including the Bank of England, Lloyd’s, the National Trust, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and the Guardian.

But as public interest in exploring and quantifying Britain’s historic links to slavery exploded in 2020, so too did a conservative backlash against “wokery”. Critics argue that the whole enterprise of examining historic links to slavery is an exercise in denigrating Britain and seeking out evidence for a foregone conclusion. Debate quickly ceases to be about the research itself – and becomes a proxy for questions of national pride. “What seems to make people really angry is the suggestion of change [in response to this sort of research], or the removal of specific things – statues, names – which is taken as a suggestion that people today should be guilty,” said Natalie Zacek, an academic at the University of Manchester who is writing a book on English universities and slavery. “I’ve never quite gotten to the bottom of that – no one is saying you, today, are a terrible person because you’re white. We’re simply saying there is another story here.”

For the critics of this work, campaigns to remove statues, revise university curricula, or investigate how institutions may have benefited from slavery are all attempts to censure the past. While this debate often plays out in public with emotive articles about “cancellation” and “doing Britain down”, conservative historians emphasise the danger of imposing value judgments on historical events or people. David Abulafia is a life fellow at Caius, and an influential figure in the college. Best known for his acclaimed history of the medieval Mediterranean, in recent years he has become a prominent conservative commentator. (Some of his eye-catching Telegraph columns have argued that “Cambridge is succumbing to the woke virus” and that the British Museum “might as well shut” if it “surrenders the Rosetta Stone”.) When I spoke to Abulafia, he struck a less strident tone. “What worries me is that modern politics is intruding into the way we interpret the past,” he said. “One has somehow to be able to chronicle the past without getting caught up with moralising about the current state of the world.”

Yet the historians working on studies of slavery or imperialism are often bemused by this concern, pointing out that all history is a product of the time in which it is written. “The job of a historian is to uncover the past and try to work out what happened, why it did, and what consequences and effects that had,” said Michael Taylor, a historian of colonial slavery and the British empire. “We’re allowed to focus on and celebrate abolition, but the previous 200 years of slavery are apparently taboo. That doesn’t make any sense.”

Every historian of slavery I spoke to emphasised that their research primarily involves archives and financial records. In their view, the work of many institutions mapping their own historic links to slavery helps to build up a more detailed picture of how Britain was shaped by its relationship with slavery and the slave trade.

Abulafia agreed that history is about “the accumulation of evidence, in as accurate and careful a way as possible”, but argued that “there is a danger of manipulating the past in the interest of current political concerns, one of which might be the idea that the ascendancy of the west has been achieved through a systematic policy of racism”. He questioned the point of tracing “profits from the slave trade that alumni might then have converted into benefactions” since, in the 18th century, using your wealth to fund scholarship might have been seen as virtuous. “It’s that challenge of trying to get one’s head around values, which are so remote from our own,” he said.

Historians of slavery argue that simply establishing these flows of money does not equate to moral judgment. As Taylor says: “This research simply helps us piece together a picture of what Britain was like when slave-trading and slave-holding was legal, which would otherwise not be there.” But critics do not accept this.

On 17 June 2020, as Black Lives Matter protests raged across the country, activists in Cambridge spraypainted the heavy wooden medieval gate that separates Caius from the busy high street it sits on: “Eugenics is genocide. Fisher must fall.” The graffiti referred to a stained-glass window installed in the Caius dining hall in 1989, commemorating the statistician RA Fisher. The window was an abstract design; squares of coloured glass arranged in a Latin Square, an image from the cover of Fisher’s influential 1935 book The Design of Experiments.

Commonly thought of as the most important figure in 20th-century statistics, Fisher was also a prominent eugenicist. He helped to found the Cambridge University Eugenics Society and, after the second world war, wrote letters in support of a Nazi scientist who had worked under Josef Mengele. The window had been controversial for years: a substantial number of students – and some faculty – wanted it to be taken down. The debate was reignited by the graffiti. A Caius student launched an online petition, writing: “Caius students and Fellows eat, converse and celebrate in space that also acts as a commemoration of our racist history.” It gained more than 1,400 signatures.

But there was pushback. Cambridge colleges are like universities within a university; faculty usually work both for their university department, where they deliver lectures, and for their college, where they provide tutorials. Students live at the college for at least part of their degree and typically have much of their teaching there. Despite a wide range of specialisms and political views among the faculty, and a proactive student body, Caius is broadly seen as one of Cambridge’s most conservative colleges, largely due to its vociferous community of life fellows. Someone becomes a life fellow after teaching at Caius for 20 years. Life fellows – who make up about 25% of the total fellowship, similar to the number of female fellows – occupy a strange position in college life; most do not teach any more, but have a room at the college and can eat at the dining hall. One former Caius student described the college as “the most luxurious nursing home in the country”.

As with the university inquiry, the idea was to look at all possible links to slavery. Alongside investigating whether the college held investments in slave-trading entities such as the East India, South Sea and Royal African Companies, he was asked to explore any connections to slavery among alumni, students and faculty. Not only would this be interesting in its own right, but hugely useful for the wider project. He said yes. “I just thought – this is wonderful, unrestricted access to the archive,” he said. “That’s a dream for a historian. It’s as good as it gets.”

But it was at Gonville and Caius that the problems would begin. The reaction to Bell-Romero’s draft report caused a rift among faculty at the college – with some pushing to prevent its publication entirely. According to the critics, the work suggested all white people “carry the taint of original sin” and that it was motivated by an “agenda” to “implicate” the college in slavery.

What happened at the college demonstrates the collision between two different worldviews: one that sees research into the history of slavery as a routine, but vital, academic exercise; and another that sees it as an overtly biased undertaking and a threat to the way historical knowledge is produced. The intensity of this clash sheds some light on why it has proved so difficult to reappraise Britain’s past.

When the Cambridge vice-chancellor Stephen Toope first announced the legacies of enslavement inquiry, he said he wanted the university to “acknowledge its role during that dark phase of human history”, adding: “We cannot change the past, but nor should we seek to hide from it.”

Momentum was building around institutions looking into their links to slavery. Historians working on this area see this as a valuable addition to historic knowledge and a way to understand how the profits of slavery shaped Britain. Many of the richest people in 18th- and 19th-century Britain were involved in the slave trade and the plantation economy. The trade and distribution of goods produced by enslaved people helped fuel Britain’s development.

While enslaved people were mostly overseas, in colonies, out of sight, slavery funded British wealth and institutions from the Bank of England to the Royal Mail. The extent to which modern Britain was shaped by the profits of the transatlantic slave economy was made even clearer with the launch in 2013 of the Legacies of British Slave-ownership project at University College London. It digitised the records of tens of thousands of people who claimed compensation from the government when colonial slavery was abolished in 1833, making it far easier to see how the wealth created by slavery spread throughout Britain after abolition. “Slave-ownership,” the researchers concluded, “permeated the British elites of the early 19th century and helped form the elites of the 20th century.” (Among others, it showed that David Cameron’s ancestors, and the founders of the Greene King pub chain, had enslaved people.)

But as Bell-Romero would write in his report on Caius, “the legacies of enslavement encompassed far more than the ownership of plantations and investments in the slave trade”. Scholars undertaking this kind of archival research typically look at the myriad ways in which individuals linked to an institution might have profited from slavery – ranging from direct involvement in the trade of enslaved people or the goods they produced, to one-step-removed financial interests such as holding shares in slave-trading entities such as the South Sea or East India Companies.

Bronwen Everill, an expert in the history of slavery and a fellow at Caius, points out “how widespread and mundane all of this was”. Mapping these connections, she says, simply “makes it much harder to hold the belief that Britain suddenly rose to power through its innate qualities; actually, this great wealth is linked to a very specific moment of wealth creation through the dramatic exploitation of African labour.”

This academic interest in forensically quantifying British institutions’ involvement in slavery has been steadily growing for several decades. But in recent years, this has been accompanied by calls for Britain to re-evaluate its imperial history, starting with the Rhodes Must Fall campaign in 2015. The Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 turbo-charged the debate, and in response, more institutions in the UK commissioned research on their historic links to slavery – including the Bank of England, Lloyd’s, the National Trust, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and the Guardian.

But as public interest in exploring and quantifying Britain’s historic links to slavery exploded in 2020, so too did a conservative backlash against “wokery”. Critics argue that the whole enterprise of examining historic links to slavery is an exercise in denigrating Britain and seeking out evidence for a foregone conclusion. Debate quickly ceases to be about the research itself – and becomes a proxy for questions of national pride. “What seems to make people really angry is the suggestion of change [in response to this sort of research], or the removal of specific things – statues, names – which is taken as a suggestion that people today should be guilty,” said Natalie Zacek, an academic at the University of Manchester who is writing a book on English universities and slavery. “I’ve never quite gotten to the bottom of that – no one is saying you, today, are a terrible person because you’re white. We’re simply saying there is another story here.”

For the critics of this work, campaigns to remove statues, revise university curricula, or investigate how institutions may have benefited from slavery are all attempts to censure the past. While this debate often plays out in public with emotive articles about “cancellation” and “doing Britain down”, conservative historians emphasise the danger of imposing value judgments on historical events or people. David Abulafia is a life fellow at Caius, and an influential figure in the college. Best known for his acclaimed history of the medieval Mediterranean, in recent years he has become a prominent conservative commentator. (Some of his eye-catching Telegraph columns have argued that “Cambridge is succumbing to the woke virus” and that the British Museum “might as well shut” if it “surrenders the Rosetta Stone”.) When I spoke to Abulafia, he struck a less strident tone. “What worries me is that modern politics is intruding into the way we interpret the past,” he said. “One has somehow to be able to chronicle the past without getting caught up with moralising about the current state of the world.”

Yet the historians working on studies of slavery or imperialism are often bemused by this concern, pointing out that all history is a product of the time in which it is written. “The job of a historian is to uncover the past and try to work out what happened, why it did, and what consequences and effects that had,” said Michael Taylor, a historian of colonial slavery and the British empire. “We’re allowed to focus on and celebrate abolition, but the previous 200 years of slavery are apparently taboo. That doesn’t make any sense.”

Every historian of slavery I spoke to emphasised that their research primarily involves archives and financial records. In their view, the work of many institutions mapping their own historic links to slavery helps to build up a more detailed picture of how Britain was shaped by its relationship with slavery and the slave trade.

Abulafia agreed that history is about “the accumulation of evidence, in as accurate and careful a way as possible”, but argued that “there is a danger of manipulating the past in the interest of current political concerns, one of which might be the idea that the ascendancy of the west has been achieved through a systematic policy of racism”. He questioned the point of tracing “profits from the slave trade that alumni might then have converted into benefactions” since, in the 18th century, using your wealth to fund scholarship might have been seen as virtuous. “It’s that challenge of trying to get one’s head around values, which are so remote from our own,” he said.

Historians of slavery argue that simply establishing these flows of money does not equate to moral judgment. As Taylor says: “This research simply helps us piece together a picture of what Britain was like when slave-trading and slave-holding was legal, which would otherwise not be there.” But critics do not accept this.

On 17 June 2020, as Black Lives Matter protests raged across the country, activists in Cambridge spraypainted the heavy wooden medieval gate that separates Caius from the busy high street it sits on: “Eugenics is genocide. Fisher must fall.” The graffiti referred to a stained-glass window installed in the Caius dining hall in 1989, commemorating the statistician RA Fisher. The window was an abstract design; squares of coloured glass arranged in a Latin Square, an image from the cover of Fisher’s influential 1935 book The Design of Experiments.

Commonly thought of as the most important figure in 20th-century statistics, Fisher was also a prominent eugenicist. He helped to found the Cambridge University Eugenics Society and, after the second world war, wrote letters in support of a Nazi scientist who had worked under Josef Mengele. The window had been controversial for years: a substantial number of students – and some faculty – wanted it to be taken down. The debate was reignited by the graffiti. A Caius student launched an online petition, writing: “Caius students and Fellows eat, converse and celebrate in space that also acts as a commemoration of our racist history.” It gained more than 1,400 signatures.

But there was pushback. Cambridge colleges are like universities within a university; faculty usually work both for their university department, where they deliver lectures, and for their college, where they provide tutorials. Students live at the college for at least part of their degree and typically have much of their teaching there. Despite a wide range of specialisms and political views among the faculty, and a proactive student body, Caius is broadly seen as one of Cambridge’s most conservative colleges, largely due to its vociferous community of life fellows. Someone becomes a life fellow after teaching at Caius for 20 years. Life fellows – who make up about 25% of the total fellowship, similar to the number of female fellows – occupy a strange position in college life; most do not teach any more, but have a room at the college and can eat at the dining hall. One former Caius student described the college as “the most luxurious nursing home in the country”.

Graffiti reading ‘Eugenics is genocide … Fisher must fall’ being cleaned off Gonville and Caius College in Cambridge University in 2020. Photograph: PA Images/Alamy

Many Cambridge colleges have some form of life fellowship for retired professors, but Caius is unusual in that they have full voting rights and can sit on the college council, a small executive body on which staff serve rotating terms. This means they have as much of a say in the running of the college as current faculty. “They functionally run the place,” said Everill. Michael Taylor, the historian, went to Caius as an undergraduate in 2007 and stayed until he finished his PhD in 2014. When he sat as a student representative on the college council, he was struck by the dysfunction of this system. “The sheer indifference to the experience of students was shocking,” he told me. “A few good people were – and are – trying to reform the college, but it’s basically a form of feudal governance.” This has often led to a situation where faculty at Caius are pulling in different directions; one primarily concerned with the preservation of tradition and the good name of the college, and another with student experience and other day-to-day concerns of a modern academic institution.

A number of life fellows had been taught by Fisher and felt that his pioneering work on statistics stood separately to his other views. “It really sparked all hell,” said Vic Gatrell, a historian and life fellow at Caius. Gatrell, in common with many of the working faculty and the students, thought the window should come down. This marked him out among the life fellows, most of whom wanted the window to stay. Gatrell is in his 80s and has worked at Caius since the 1970s. In that time there had been disagreements – “the admission of women was very divisive,” he recalls – but in those 50 years, nothing had provoked such strong emotions. “In all these years, we never inquired into each other’s politics,” he told me. But now, colleagues he’d lived and worked with for decades walked past in the corridor without saying hello, or sat separately in the dining hall. “It was a microcosm of what’s happening in the nation at large,” he said.

In late June 2020, Caius removed the Fisher window. But the dividing lines were there to stay. In a long article for the Critic titled Cancelled by his college, the eminent geneticist, life fellow Anthony Edwards – who had been mentored by Fisher, and had proposed the installation of the window – rejected the allegation that Fisher was racist, or even a leading eugenicist. He decried the fact that “now the college Fisher loved has turned its back on him”. Within college, life fellows spoke of Fisher being cancelled, dishonoured and targeted unfairly by BLM protesters. “The removal of the Fisher window opened a wound that still continues in various ways,” said one research fellow.

It was against this backdrop that Bell-Romero got to work in the Caius archives in the autumn of 2020. The Fisher window had been removed, but bad blood remained. Still, Bell-Romero – who was not based fulltime at the college – was blissfully unaware. He had a specific brief: to examine whether students, alumni, staff or benefactors had links to slavery. Once a week, he went into the archive, housed in a grand 19th-century building next to the lush green lawn of Caius Court. The archive spans the full eight centuries of the college’s life, from medieval estate records to the personal papers of modern alumni and faculty. The research was a low-key pursuit – just Bell-Romero and the college archivist, going through paper records.

As per his brief, he looked widely: “It’s not just about people owning plantations – it’s about small pots of money, small investments people had,” he said. Gradually, he traced a number of connections to slavery, through former students and staff who had investments in slave-holding companies. Previous histories of Caius had identified two sizeable donations to the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in the late 18th century. But in the archives, Bell-Romero found that the financial benefits from enslavement outweighed the college’s contribution to abolition.

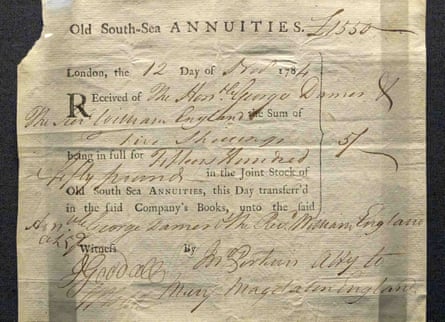

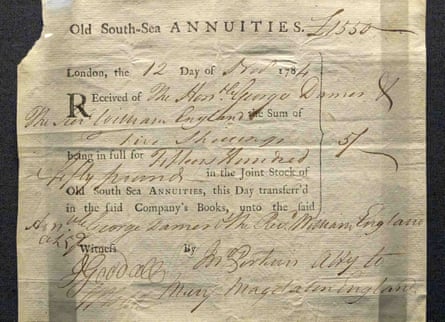

His draft report was a modest document of about 50 pages. His key finding was that the college once had financial interests in the South Sea Company, an organisation that “sent 64,780 enslaved persons to the Spanish Americas”. These were in the form of annuities and stocks, gained through donations left to the college by alumni. He wrote that through these benefactions “the College’s fate – like so many other educational institutions in Great Britain – became intertwined with the imperial commercial economy, with slavery being one of its most profitable ventures”. Mapping this out, along with details of students from slave-owning families educated at Caius, Bell-Romero concluded that this story was “not singular, but indicative of the longstanding ties of British institutions and individuals to chattel slavery and coerced labour”.

These findings didn’t surprise Bell-Romero. “It was what you’d expect for a rich college that has existed for many hundreds of years,” he said. When he submitted the draft in the autumn of 2021, he did not realise how contentious it would be.

Bronwen Everill was head of the Caius working group on the legacies of enslavement project. Bell-Romero’s report was a draft – it needed editing – but Everill thought it was a solid piece of work with uncontroversial conclusions. “Basically, the finding of this report was – like almost all these institutions – Caius had a little bit of a hand in slavery, but it was not fundamentally based on financing from the slave trade,” she told me. Bell-Romero’s report only included archival research. But Everill and her three colleagues on the working group were expected to come up with suggestions for next steps.

Part of the remit of the Cambridge University inquiry was to consider how these legacies are reflected in the modern day. The most prominent example of this work – at Glasgow University – had led to a substantial reparative package. That project had passed without controversy. But in the intervening years, the political climate had changed. (“Any study now is being scrutinised from the outset, and the credibility and objectivity of academic historians is being questioned by some critics,” Mullen, the Glasgow researcher, told me.)

There are various mechanisms for working out how much historical sums are worth in today’s currency. For his report, Bell-Romero used an academic database called Measuring Worth, created by a group of economic historians to calculate estimates of the “present value” of past assets – which the Glasgow report had also employed. Bell-Romero wrote that “the calculation of historical value is not an exact science – indeed, these figures are at best a rough estimate.” On the basis of the report, the working group proposed that Caius offer funding to two Black Mphil students.

Typically, a drafted piece of research might be assessed and edited by other experts in the field; historians with some knowledge of its particular time period and geography. But the quirks of college life meant that the process at Caius was different. The report was being published on behalf of the college, so in December, the draft report was circulated for feedback to all fellows and life fellows, regardless of their expertise.

In January 2022, responses rolled in. Some highlighted mistakes: confusion over the name of a historical figure, and minor spelling errors. Others questioned the entire motivation for the project. In a lengthy response, Abulafia said that people in the past may have been involved in many things that today seem unsavoury, and asked: “If British people carry the taint of original sin by all those who are white supposedly being complicit in the slave trade, how much more are we complicit in all these activities that still go on around us?” He concluded that the report must “stand back from the past and not make it into a canvas they can slather with the moral wisdom of a particular fashionable ideology”.

A number of life fellows had been taught by Fisher and felt that his pioneering work on statistics stood separately to his other views. “It really sparked all hell,” said Vic Gatrell, a historian and life fellow at Caius. Gatrell, in common with many of the working faculty and the students, thought the window should come down. This marked him out among the life fellows, most of whom wanted the window to stay. Gatrell is in his 80s and has worked at Caius since the 1970s. In that time there had been disagreements – “the admission of women was very divisive,” he recalls – but in those 50 years, nothing had provoked such strong emotions. “In all these years, we never inquired into each other’s politics,” he told me. But now, colleagues he’d lived and worked with for decades walked past in the corridor without saying hello, or sat separately in the dining hall. “It was a microcosm of what’s happening in the nation at large,” he said.

In late June 2020, Caius removed the Fisher window. But the dividing lines were there to stay. In a long article for the Critic titled Cancelled by his college, the eminent geneticist, life fellow Anthony Edwards – who had been mentored by Fisher, and had proposed the installation of the window – rejected the allegation that Fisher was racist, or even a leading eugenicist. He decried the fact that “now the college Fisher loved has turned its back on him”. Within college, life fellows spoke of Fisher being cancelled, dishonoured and targeted unfairly by BLM protesters. “The removal of the Fisher window opened a wound that still continues in various ways,” said one research fellow.

It was against this backdrop that Bell-Romero got to work in the Caius archives in the autumn of 2020. The Fisher window had been removed, but bad blood remained. Still, Bell-Romero – who was not based fulltime at the college – was blissfully unaware. He had a specific brief: to examine whether students, alumni, staff or benefactors had links to slavery. Once a week, he went into the archive, housed in a grand 19th-century building next to the lush green lawn of Caius Court. The archive spans the full eight centuries of the college’s life, from medieval estate records to the personal papers of modern alumni and faculty. The research was a low-key pursuit – just Bell-Romero and the college archivist, going through paper records.

As per his brief, he looked widely: “It’s not just about people owning plantations – it’s about small pots of money, small investments people had,” he said. Gradually, he traced a number of connections to slavery, through former students and staff who had investments in slave-holding companies. Previous histories of Caius had identified two sizeable donations to the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in the late 18th century. But in the archives, Bell-Romero found that the financial benefits from enslavement outweighed the college’s contribution to abolition.

His draft report was a modest document of about 50 pages. His key finding was that the college once had financial interests in the South Sea Company, an organisation that “sent 64,780 enslaved persons to the Spanish Americas”. These were in the form of annuities and stocks, gained through donations left to the college by alumni. He wrote that through these benefactions “the College’s fate – like so many other educational institutions in Great Britain – became intertwined with the imperial commercial economy, with slavery being one of its most profitable ventures”. Mapping this out, along with details of students from slave-owning families educated at Caius, Bell-Romero concluded that this story was “not singular, but indicative of the longstanding ties of British institutions and individuals to chattel slavery and coerced labour”.

These findings didn’t surprise Bell-Romero. “It was what you’d expect for a rich college that has existed for many hundreds of years,” he said. When he submitted the draft in the autumn of 2021, he did not realise how contentious it would be.

Bronwen Everill was head of the Caius working group on the legacies of enslavement project. Bell-Romero’s report was a draft – it needed editing – but Everill thought it was a solid piece of work with uncontroversial conclusions. “Basically, the finding of this report was – like almost all these institutions – Caius had a little bit of a hand in slavery, but it was not fundamentally based on financing from the slave trade,” she told me. Bell-Romero’s report only included archival research. But Everill and her three colleagues on the working group were expected to come up with suggestions for next steps.

Part of the remit of the Cambridge University inquiry was to consider how these legacies are reflected in the modern day. The most prominent example of this work – at Glasgow University – had led to a substantial reparative package. That project had passed without controversy. But in the intervening years, the political climate had changed. (“Any study now is being scrutinised from the outset, and the credibility and objectivity of academic historians is being questioned by some critics,” Mullen, the Glasgow researcher, told me.)

There are various mechanisms for working out how much historical sums are worth in today’s currency. For his report, Bell-Romero used an academic database called Measuring Worth, created by a group of economic historians to calculate estimates of the “present value” of past assets – which the Glasgow report had also employed. Bell-Romero wrote that “the calculation of historical value is not an exact science – indeed, these figures are at best a rough estimate.” On the basis of the report, the working group proposed that Caius offer funding to two Black Mphil students.

Typically, a drafted piece of research might be assessed and edited by other experts in the field; historians with some knowledge of its particular time period and geography. But the quirks of college life meant that the process at Caius was different. The report was being published on behalf of the college, so in December, the draft report was circulated for feedback to all fellows and life fellows, regardless of their expertise.

In January 2022, responses rolled in. Some highlighted mistakes: confusion over the name of a historical figure, and minor spelling errors. Others questioned the entire motivation for the project. In a lengthy response, Abulafia said that people in the past may have been involved in many things that today seem unsavoury, and asked: “If British people carry the taint of original sin by all those who are white supposedly being complicit in the slave trade, how much more are we complicit in all these activities that still go on around us?” He concluded that the report must “stand back from the past and not make it into a canvas they can slather with the moral wisdom of a particular fashionable ideology”.

A share certificate for the South Sea Company, in which Gonville and Caius College was found to have had financial interests. Photograph: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty

Prof Joe Herbert, a life fellow in medicine, wrote that the report “clearly has an agenda: to implicate Caius as much as possible in supporting and benefiting [from] slavery”. He questioned the logic of funding Black MPhil students: “There is an undoubted shortfall of black applicants (not other ethnic groups); but this is not a direct result of slavery 200 years ago, and we absolve ourselves from our responsibility by thinking it is, and offering a solution which is no solution.”

Everill was surprised by the tenor of the responses, and particularly by the fact that the most strident criticism had come from life fellows who were not scholars of Britain or empire. To her, it felt like a fundamental misunderstanding of the project and a recycling of culture-war talking points. (Abulafia suggested the report was “infused with the ideas of critical race theory”.) Many of the people most affronted by the report were the same who had been most defensive of the Fisher window. “There’s a lot of people who read about the culture wars and think they are personally under attack by a woke mob,” Everill said a few months later.

A number of responses queried – in strong terms – the mechanism for working out historical inflation, which the critics argued had produced an implausibly wide range of estimated values, and the reparative suggestion. “They seemed to think we were saying we, today, should be guilty – rather than that the institution made this money, and so the institution should think about distributing this money,” said Everill.

Bell-Romero was frustrated that some of the notes appeared to be responding to points he hadn’t made. “It had nothing to do with what I found; it was just about the political bent of what they thought the research was about,” he said. “The point was never to denigrate the college.”

The college council told the working group they had to respond in particular to Abulafia’s criticisms, because of his high standing as a historian. Together, they drafted a 5,000-word response, accepting some criticisms and disputing others. They wrote: “The report is not admonishing past Caians, or saying that ‘Caians should not have’ done something … The very point is the banality … The report is recording the connections to a system that was widespread throughout British economic life. We are not asking for people to judge the people of the past. We are simply presenting a more complete picture so that we, today, can think about what we want to do with that information.”

Rather than defend the report in front of the college council, Everill thought it would be more productive to hold an open meeting, in the hope of encouraging a discussion rather than a debate. It took place in early March, an opportunity for anyone to ask questions of Bell-Romero and the working group. Bell-Romero expected a big turnout. But only one person turned up: Joe Herbert. According to others present at the meeting, he walked into the room and declared: “This is a terrible report.” That set the tone. Members of the working group said that Herbert, who declined to be interviewed for this story, called history a “crap discipline” and suggested that the low admission rates for Black students at Cambridge were not connected to the history of slavery.

Everill was appalled. At one point, she said, she stood up and said: “No, absolutely not, I will not put up with that kind of tone.” Herbert responded: “Sit down, woman,” adding, “You’re not in charge here.” In a later email to Everill, he acknowledged this, saying: “I told you to shut up because you were shrieking at me. You weren’t attempting to say anything.” (Contacted before publication, Herbert said that “inappropriate language” used at the meeting “was not limited to me”, but denied saying history was a “crap discipline”.)

After the open meeting, Everill was copied on an email thread in which this group of three life fellows continued to attack the report. They did not acknowledge the 5,000-word response, writing: “You never tried to explain anything.” In the emails, another life fellow, the philosopher Jimmy Altham, suggested that Everill may be “dyslexic” because of some typos; Herbert said that “the important thing is that this disastrous report is not published in the college’s name”; and Abulafia replied “I 100% agree”. Everill made a formal complaint of harassment against Altham and Herbert. The complaint against Herbert was upheld; but not against Altham. Herbert was encouraged to apologise, but he did not.

The scholars engaged in the research had fulfilled a narrow brief to examine the college’s financial links to slavery and come up with a proposal for action. But the life fellows who objected seemed to be responding to something larger; the idea that the legacies of slavery might still be shaping our present.

When I spoke with Abulafia, he didn’t want to discuss the specifics of events at Caius, which he described as “a source of division and contention”, but he did talk more broadly about this area of research. “It started with one or two Oxbridge colleges conducting these investigations and by and large, not much came out of it,” he said. “Why are they looking into it? It’s become a sort of fad, if you like. If we want to look at issues to do with the way human beings were being badly oppressed in the early 19th century, we might also want to look at children down the mines in this country. There are horrific stories. I just wish we could recognise that sort of unholy behaviour, which certainly took place in the slave trade, is also taking place on our own soil between white people – if we’re going to make it about a given colour, which I hate doing, actually.” Citing other examples of historic exclusion and oppression, such as child labour, he said: “Let’s tell those stories and not put so many resources into the legacies of slavery. I think we’ve got the basic idea on that now.”

Soon after the disastrous open meeting, the college council suggested that Bell-Romero redraft his report in collaboration with a life fellow in history who was not one of the primary critics – saying he would “know the fellowship tone”. But Bell-Romero was affronted. “It’s censorship, being babysat to write your own piece,” he said. “That’s where I drew the line.” He declined. With no clear plan of action, he thought the report might never be published. He continued with the Cambridge inquiry and tried to forget about it. But that would not be so easy.

In late May, as the Easter term edged towards its end, Tommy Castellani, a second-year languages undergraduate, was sitting in the Caius dining hall when a friend mentioned that his history tutor had been tweeting about a dispute. Castellani had recently started writing news stories for Varsity, the Cambridge student paper, and he wanted to know more. His friend pulled up Everill’s Twitter account. “It is literally my favourite thing, waking up on a lovely bank holiday Sunday to a whole string of emails from angry *life fellows* calling me names. The best.” (She was referring to the “dyslexic” comment.) Castellani started to dig into it.

“I realised this was going to be a big story,” he said. “There’s a culture war in college, and you can see it in the council papers – people feel divided.” He got hold of emails, spoke to Everill and interviewed Bell-Romero, who asked not to be named in the story. In June, Varsity published Castellani’s account of the fallout, including quotes from the life fellows’ emails and details of what was said at the open meeting. Castellani had approached the college for comment on the “racist and sexist” undertones of comments at the open meeting.

But when the Telegraph picked up on the Caius dispute three weeks later, the story had a very different slant. Incorrectly stating that the Caius research had been initiated “in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement” (the college had actually started the process of researching its links to slavery in spring 2019, a year before the protests), the story claimed the report included “incorrect monetary conversions”.

The paper identified Bell-Romero by name as a “woke activist” who had produced “shambolic” work that caused the crisis. Bell-Romero couldn’t access the article at first because of the paywall. When he did, his first response was horror. His second was to laugh. “I’d been struggling to explain to my friends what this had been like, and now I could point to the Telegraph article and say – that’s the tenor of the feedback we received.”

Although the reporter had clearly been briefed by at least one life fellow, the critics remained anonymous, even when quoted at length saying that these “attempts to rewrite history fall at the first hurdle”. Meanwhile Bell-Romero – a precariously employed early-career academic (wrongly described in the article as a “student”) – was named, and his professionalism questioned. A few days later, the Telegraph story was picked up by the Times, which has devoted increasing attention to campus conflicts in recent years.

The work of looking into legacies of slavery or related topics is typically done by early-career researchers. There is a growing concern about the risk of backlash for young academics working on histories of empire or slavery who are singled out in the press. They are left highly exposed, while their critics often have established positions and job security. Charlotte Riley, a lecturer in history at the University of Southampton, described a conversation with a new PhD student looking at empire and railways. “We had to sit him down and say: ‘The Daily Mail might come for you.’”

After the stories came out, Bell-Romero was contacted by a number of other researchers working on topics related to decolonisation and slavery who had been the subject of hit-jobs in the rightwing press. Time and again, researchers I interviewed for this story insisted on answering questions by email rather than speaking on the phone or in person, citing the fear of being misrepresented. “I do worry about a chilling effect,” says Everill. “There are a bunch of these postdocs available at the moment, and people who don’t want to be named and shamed in the national media might decide not to apply.”

Everill was surprised by the tenor of the responses, and particularly by the fact that the most strident criticism had come from life fellows who were not scholars of Britain or empire. To her, it felt like a fundamental misunderstanding of the project and a recycling of culture-war talking points. (Abulafia suggested the report was “infused with the ideas of critical race theory”.) Many of the people most affronted by the report were the same who had been most defensive of the Fisher window. “There’s a lot of people who read about the culture wars and think they are personally under attack by a woke mob,” Everill said a few months later.

A number of responses queried – in strong terms – the mechanism for working out historical inflation, which the critics argued had produced an implausibly wide range of estimated values, and the reparative suggestion. “They seemed to think we were saying we, today, should be guilty – rather than that the institution made this money, and so the institution should think about distributing this money,” said Everill.

Bell-Romero was frustrated that some of the notes appeared to be responding to points he hadn’t made. “It had nothing to do with what I found; it was just about the political bent of what they thought the research was about,” he said. “The point was never to denigrate the college.”

The college council told the working group they had to respond in particular to Abulafia’s criticisms, because of his high standing as a historian. Together, they drafted a 5,000-word response, accepting some criticisms and disputing others. They wrote: “The report is not admonishing past Caians, or saying that ‘Caians should not have’ done something … The very point is the banality … The report is recording the connections to a system that was widespread throughout British economic life. We are not asking for people to judge the people of the past. We are simply presenting a more complete picture so that we, today, can think about what we want to do with that information.”

Rather than defend the report in front of the college council, Everill thought it would be more productive to hold an open meeting, in the hope of encouraging a discussion rather than a debate. It took place in early March, an opportunity for anyone to ask questions of Bell-Romero and the working group. Bell-Romero expected a big turnout. But only one person turned up: Joe Herbert. According to others present at the meeting, he walked into the room and declared: “This is a terrible report.” That set the tone. Members of the working group said that Herbert, who declined to be interviewed for this story, called history a “crap discipline” and suggested that the low admission rates for Black students at Cambridge were not connected to the history of slavery.

Everill was appalled. At one point, she said, she stood up and said: “No, absolutely not, I will not put up with that kind of tone.” Herbert responded: “Sit down, woman,” adding, “You’re not in charge here.” In a later email to Everill, he acknowledged this, saying: “I told you to shut up because you were shrieking at me. You weren’t attempting to say anything.” (Contacted before publication, Herbert said that “inappropriate language” used at the meeting “was not limited to me”, but denied saying history was a “crap discipline”.)

After the open meeting, Everill was copied on an email thread in which this group of three life fellows continued to attack the report. They did not acknowledge the 5,000-word response, writing: “You never tried to explain anything.” In the emails, another life fellow, the philosopher Jimmy Altham, suggested that Everill may be “dyslexic” because of some typos; Herbert said that “the important thing is that this disastrous report is not published in the college’s name”; and Abulafia replied “I 100% agree”. Everill made a formal complaint of harassment against Altham and Herbert. The complaint against Herbert was upheld; but not against Altham. Herbert was encouraged to apologise, but he did not.

The scholars engaged in the research had fulfilled a narrow brief to examine the college’s financial links to slavery and come up with a proposal for action. But the life fellows who objected seemed to be responding to something larger; the idea that the legacies of slavery might still be shaping our present.

When I spoke with Abulafia, he didn’t want to discuss the specifics of events at Caius, which he described as “a source of division and contention”, but he did talk more broadly about this area of research. “It started with one or two Oxbridge colleges conducting these investigations and by and large, not much came out of it,” he said. “Why are they looking into it? It’s become a sort of fad, if you like. If we want to look at issues to do with the way human beings were being badly oppressed in the early 19th century, we might also want to look at children down the mines in this country. There are horrific stories. I just wish we could recognise that sort of unholy behaviour, which certainly took place in the slave trade, is also taking place on our own soil between white people – if we’re going to make it about a given colour, which I hate doing, actually.” Citing other examples of historic exclusion and oppression, such as child labour, he said: “Let’s tell those stories and not put so many resources into the legacies of slavery. I think we’ve got the basic idea on that now.”

Soon after the disastrous open meeting, the college council suggested that Bell-Romero redraft his report in collaboration with a life fellow in history who was not one of the primary critics – saying he would “know the fellowship tone”. But Bell-Romero was affronted. “It’s censorship, being babysat to write your own piece,” he said. “That’s where I drew the line.” He declined. With no clear plan of action, he thought the report might never be published. He continued with the Cambridge inquiry and tried to forget about it. But that would not be so easy.

In late May, as the Easter term edged towards its end, Tommy Castellani, a second-year languages undergraduate, was sitting in the Caius dining hall when a friend mentioned that his history tutor had been tweeting about a dispute. Castellani had recently started writing news stories for Varsity, the Cambridge student paper, and he wanted to know more. His friend pulled up Everill’s Twitter account. “It is literally my favourite thing, waking up on a lovely bank holiday Sunday to a whole string of emails from angry *life fellows* calling me names. The best.” (She was referring to the “dyslexic” comment.) Castellani started to dig into it.

“I realised this was going to be a big story,” he said. “There’s a culture war in college, and you can see it in the council papers – people feel divided.” He got hold of emails, spoke to Everill and interviewed Bell-Romero, who asked not to be named in the story. In June, Varsity published Castellani’s account of the fallout, including quotes from the life fellows’ emails and details of what was said at the open meeting. Castellani had approached the college for comment on the “racist and sexist” undertones of comments at the open meeting.

But when the Telegraph picked up on the Caius dispute three weeks later, the story had a very different slant. Incorrectly stating that the Caius research had been initiated “in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement” (the college had actually started the process of researching its links to slavery in spring 2019, a year before the protests), the story claimed the report included “incorrect monetary conversions”.

The paper identified Bell-Romero by name as a “woke activist” who had produced “shambolic” work that caused the crisis. Bell-Romero couldn’t access the article at first because of the paywall. When he did, his first response was horror. His second was to laugh. “I’d been struggling to explain to my friends what this had been like, and now I could point to the Telegraph article and say – that’s the tenor of the feedback we received.”

Although the reporter had clearly been briefed by at least one life fellow, the critics remained anonymous, even when quoted at length saying that these “attempts to rewrite history fall at the first hurdle”. Meanwhile Bell-Romero – a precariously employed early-career academic (wrongly described in the article as a “student”) – was named, and his professionalism questioned. A few days later, the Telegraph story was picked up by the Times, which has devoted increasing attention to campus conflicts in recent years.

The work of looking into legacies of slavery or related topics is typically done by early-career researchers. There is a growing concern about the risk of backlash for young academics working on histories of empire or slavery who are singled out in the press. They are left highly exposed, while their critics often have established positions and job security. Charlotte Riley, a lecturer in history at the University of Southampton, described a conversation with a new PhD student looking at empire and railways. “We had to sit him down and say: ‘The Daily Mail might come for you.’”

After the stories came out, Bell-Romero was contacted by a number of other researchers working on topics related to decolonisation and slavery who had been the subject of hit-jobs in the rightwing press. Time and again, researchers I interviewed for this story insisted on answering questions by email rather than speaking on the phone or in person, citing the fear of being misrepresented. “I do worry about a chilling effect,” says Everill. “There are a bunch of these postdocs available at the moment, and people who don’t want to be named and shamed in the national media might decide not to apply.”

The conflict at Caius seemed to be part of a wider faltering of legacies of slavery research – through overt backlash, or institutions announcing projects with great fanfare but not following through with support and funding. Hilary Beckles, the vice-chancellor of the University of the West Indies and the author of Britain’s Black Debt, calls this pattern “research and run” – where universities do the archival work, then say a quick sorry and run from the implications of the findings, leaving the researchers exposed.

The historian Olivette Otele, a scholar of slavery and historical memory who was the first Black woman to be appointed a professor of history in the UK, joined the University of Bristol in 2020, and worked on the university’s own research into its deep connections to the slave trade. When she left just two years later, a colleague in another department tweeted that the university had used Otele “as a human shield to deflect legitimate criticism”. Announcing her departure, Otele wrote on Twitter: “The workload became insane and not compensated by financial reward. I actually burnt out,” adding that colleagues had been “sabotaging my reputation inside and outside the uni.”

As far as anyone could see, Caius had backed away from publishing Bell-Romero’s report after the controversy; Everill, head of the working group, was not sure it would ever be published. But in July, a newspaper submitted a freedom of information request about it. (Newspapers increasingly submit FoIs about academic research on subjects like slavery and empire as universities have become the frontline in the culture war; a controversial Times front page in August claimed that universities were changing syllabuses, even though their own data did not bear this out. Riley recalled one absurd example, where a journalist sent an FoI requesting all emails from academics using the word “woke”. “There were none, because we don’t actually sit there writing ‘I’m a woke historian’. That is insane.”)

The following month, the Caius report was published online, with the proposal for MPhil funding removed. It was not covered anywhere. “Probably because it turns out that wasn’t actually that inflammatory,” Everill said. In a statement to the Guardian, the master of the college, Prof Pippa Rogerson, said: “The report makes uncomfortable reading for all those affiliated to Caius. The College is 675 years old and it is important we acknowledge our complex past.”

In September, Bell-Romero and Cadeau’s much larger Cambridge University legacies of enslavement project was published. It found that Cambridge fellows had been involved in the East India Company and other slave-trading entities, and that the university had directly invested in the South Sea Company. They wrote: “Such financial involvement both helped to facilitate the slave trade and brought very significant financial benefits to Cambridge.” The report was covered by major news outlets, but did not provoke a particularly strong response.

The conflict over the Caius research suggests that these disputes often have little to do with the archival research itself, or its conclusions. In the view of the critics, the research is discredited by its intention to correct past wrongs. Even when the researchers insist that they are not trying to assign blame or guilt, the critics insist in return – not without some justification – that whether or not this is the intention, it is almost always the effect. This is presumably why they disapprove of doing the research to begin with.