Cricket's stars are a ruthless lot, many have crashed and burned at its hallowed pitch

ROHIT MAHAJAN, SMRUTI KOPPIKAR, SUGATA SRINIVASARAJU, CHANDER SUTA DOGRA, DOLA MITRA, AMBA BATRA BAKSHI

The game that begets a few stars is also father to thousands of disaffected, depressed men

Cases of suicide

Rambabu Pal: A prolific batsman from UP, he couldn't make use of the few chances he got in first-class cricket. Committed suicide at 34 in 2007.

Manish Mishra: Was acutely depressed after he failed to make the Uttar Pradesh Ranji Trophy team, committed suicide at 24 in 2007.

Subhash Dixit: One-time captain of India U-17, his career stalled before the Ranji level. Committed suicide at 22 in 2007.

Jhuma Sarkar: A regular in Bengal Under-19 women's team, failed to progress. Committed suicide at 23 in 2007.

***

The Enveloping Blues

Mohan Chaturvedi, 38: Was told he'd be touring Pakistan in 1989, but was left out. A wicketkeeper, he went into depression, says he was saved by his faith in God.

Obaid Kamal, 36: One of the best fast bowlers to never play for India. Was frustrated, says he was saved from suicide because of the Islamic injunction against it.

Suhail Sharma, 27: The all-rounder played for Delhi in Ranji Trophy, but struggled to find a job and was depressed for four years.

Dilraj Atwal, 21: The fast bowler was injured after being invited to bowl in the Delhi Ranji Trophy camp last year. Used to cry himself to sleep.

Feroze Ghayas, 36: One of the fastest bowlers who never played for India. Was depressed for some time, says he hurts even now.

Sumit Kundu, 21: Was Haryana Under-17 captain one year, on the sidelines the next. Went into a depression, gave up cricket forever.

Saikat Ganguly, 17: Was named the best junior cricketer of Bengal in 2006; was dropped at the trial stage even before the first tournament. Still in a slump.

Vinayak Samant, 36: For this lower middle-class boy who played for Mumbai and Assam, the India call never came. Went through lows.

***

Message In A...

Maninder Singh, 43: Hailed as a very special talent, played for India at age 17. Couldn't handle stardom, lost his rhythm, his career unravelled...and he took to drinking.

Sadanand Viswanath, 46: In 1985, he was a superstar in the making. Then he was dropped, took to drink and, lost his way, and lost everything.

Vijay Dahiya, 36: Still wonders why he was dropped from the Indian team, took to drinking and clubbing. Lost his way.

Reasons

Little room at the top

Only a select few can play first-class cricket, about 400 in India. Number of aspirants runs into lakhs.

Limited career options

Being onfield for hours a day, years on end, leaves little time to acquire other vocational skills. So no fallback options.

Arbitrariness of selection

Selection can be arbitrary at any level, and are often very biased. Players can’t come to terms with this.

Early success

Too much too early can distract you. Beginning of the end?

Injuries

Can end a career at any age, at any time.

***

Solutions

Keep expectations in check

Cricket must be a passion, not the career option.

Counselling

From very early, players must have access to sports psychologists who can guide them.

Fair selection

Save players from trauma, ensure that the selection process is absolutely fair.

Sports medicine

Still a developing science in the country, many careers are destroyed due to the lack of it.

More other jobs

The BCCI, with all its money, could assist players above U-17 to develop vocational skills, as is done in England.

(Outlook accessed many others who narrated their experience of confronting the dark side of cricket—but they didn’t want to be named.)

***

"The others become drunkards, slip into depression or just fade away into inconsequential careers, where they remain unhappy forever" —Yograj Singh, Cricket Coach

"Cricket can never be a career prospect. Disappointment is guaranteed. Success is not. Once that is established, depression cannot defeat you."—Arun Lal, Former Test cricketer

"You get selected 10 times and then you are dropped for no obvious reason. You see yourself as a failure. Even at the first-class level, it’s a gloomy life." —Aakash Chopra, Ex-India opener

***

Vijay Dahiya, 36, India

Last played for India in 2001, he couldn’t fathom why he was axed. "When you realise you won’t be chosen, the sacrifices you made earlier seem futile," he says. Started visiting nightclubs and drinking. No more bitter, he says all he has today is because of cricket.

In the alleys of old Lucknow, where the affluent share a wall with the indigent, there’s a three-storeys-high dwelling which houses 22 people of one extended family. In a second-floor room which betrays the lower middle-class background of its owners, Manish Mishra grins back at you, his eyes glinting. But it’s only a photograph, and Mishra’s siblings don’t smile, because he hanged himself here two years ago. In life, he overdosed on a passion for cricket. In death—apparently triggered by a tiff with his estranged wife over the phone—he embodies what is very often the fruit of that passion: the lingering frustration of failing in the game and a deep regret for having spent so much time at the nets that it left him with little else in the end. Not even time to escape with some other minimal skills that could help him pitch his tent in some other field.

"He used to say he wished had worked so hard in some other field... for he'd have found a good job..."

Mishra joined the Agra cricket hostel for coaching at the age of nine. He worked hard at his game, ultimately playing for Uttar Pradesh in the junior teams. Early morning, he’d walk to the field, often in borrowed trousers. That’s approximately where his cricketing career got stuck, and he ended up with a fourth-class job in the Railways, a whole world away from his dream of wearing the Indian colours. "He used to say he wished he had worked so hard in some other field...," his cousins say.It didn’t stop there. Bad luck dogged him, his mother died, there was marital discord. Then, without warning, came the night when he dragged the bed across to block his door and hanged himself from the fan.

Mishra didn’t die just because of cricket. No doubt, he took the extreme step because of circumstances at home also. But his frustration at the abject failure in his chosen field, at real or perceived injustices done to his talent, his anger at the venality of system, it all played a part till one day he snapped. In our cricket fields, this anger and frustration is shared by tens of thousands of boys and men who’ve played cricket. The game that begets a few dazzling stars also fathers thousands of disaffected, depressed men.

There are too many guileless, potential ‘cricket victims’ out there for us to ignore it any more. Raw, underage and prone to being felled by the game’s vicissitudes. Lots of cricketers and coaches Outlook spoke to testified to the fact that depression is a major malaise. Some confessed to suicidal thoughts. The list of 15 cricketers who admitted to suffering the ‘cricket blues’ isn’t exhaustive—they are just a few who agreed to go public with their stories, in the hope that the Indian cricket establishment would be prompted to help the young cope with the dark side of the sunny sport.

Former Test player Arun Lal, who runs the Bournvita Cricket Academy in Calcutta, admits that "depression exists in a big way in cricket". Coach Yograj Singh, who played one Test for India, admits a plain professional truth: only a handful among the hundreds of hopefuls have it in them to make it big in cricket. "The others become drunkards, slip into depression or just fade away into inconsequential careers, where they remain unhappy forever."

Saikat Ganguly, 17, Bengal

Jrs Named the best junior cricketer of Bengal in 2006, he was dropped at the trial stage before the first tournament. Slipped into depression, still avoids visitors. Flips through his scrapbook filled with clippings reporting his rise and fall in cricket. Advises his cousin to not play cricket.

The really disturbing thing is, the opposite of a life of glory is often not just a life of misery—some simply terminate. The gloom that descended upon Subhash Dixit’s house in Kanpur two years ago will probably never dissipate. In 2007, the family lost Subhash, the family’s beloved as also its main hope for he was at one time the junior India cricket captain. He was then 22, when cricketing dreams often start to die and a search for livelihood begins. But Subhash lacked the skills of the usual job-seeker. Aunt Sushma, her voice trembling, says he just couldn’t find a job. "He used to say he would have been selected for the Ranji team if we had the money or the contacts," she told Outlook. "Earlier, he used to pledge that he’d ‘do something in life’. Now I just wish he’d come back somehow."

In 2007, the family lost Subhash Dixit, their lone hope, for he was at one time the India Jrs cricket captain.

But Subhash isn’t coming back. He jumped to his death after leaving home, ostensibly to practise at the Green Park grounds in the city.

Obaid Kamal, who played for UP and Punjab and now coaches in Lucknow, says "people don’t know how frustrating it is to become a cricketer. (I found life in the jaws of death)." A swing bowler, Kamal was a regular feature in the Duleep Trophy teams of the 1990s. "Even when I got the most wickets, I did not get a call.When (Javagal) Srinath was injured in New Zealand in 1994, everyone said I should be sent to replace him. A spinner was sent instead!" he recalls. He declares he’s now put it all behind him, yet there were moments of despair when Kamal contemplated suicide; he says his mother’s words when he was a child—that suicide is "haraam, a sin that won’t be forgiven"—is what saved him.

Mohan Chaturvedi, 38, Delhi

Hailed as India’s best keeper, he went into depression after he was not chosen for the ‘89 Pak tour. Seen in Delhi’s Connaught Place with his pads and keeping glove on; he’d keep awake at night, crying. Says he’ll never let his son take up cricket.

Faith saved Mohan Chaturvedi too, who teetered on the edge for a while. Chaturvedi, a Delhi wicketkeeper, had been measured for the team gear before the 1989 tour of Pakistan. But he was not picked up; for an 18-year-old it was shattering. Always the standby, he gave up the game at 24. Depression ensued. "I withdrew from the world, I confined myself to my room," Chaturvedi, who’s now with the Income Tax department, says. "I stopped watching cricket, I hated the game, I had no hope." What saved him was his faith in god. Chaturvedi says, "God gave me the power to come out of depression. I used to go to the holy shrines every year, and that saved me."

It's emotionally sapping to play a game where luck has such a crucial role. The strain breaks cricketers.

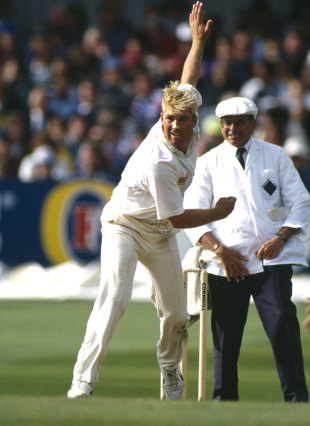

Cricketers seem more vulnerable to depression than other sportspersons because the game, as writer David Frith (see column) puts it, "is unique in its propensity to take over a man’s psyche". In recent times, there have been many reports of high-profile cases of depression, including England’s Marcus Trescothick, Australia’s Shaun Tait and New Zealand’s Lou Vincent. For it’s emotionally sapping to play a game where luck has such a crucial role. The strain can break cricketers. Take the case of fast bowler Firoze Ghayas, who took 13 wickets on his first-class debut. Yet he struggled to become a regular for even Delhi, forget playing for India. "For a player with skill and ambition, sitting on the bench is like being in jail," he says now. "It still hurts, this pain will never go away. Why did it happen? Eventually, to make peace with yourself, one comes to the conclusion that it’s fate. Even if you are good and have performed well, if you don’t have luck or someone backing you, it all adds to nothing." Some, unlike Ghayas, are never reconciled.

Feroze Ghayas, 36, Delhi

Javagal Srinath once told him, "You’ve got raw pace, man!" Dennis Lillee thought he was a hot prospect. But he never played for India. His frustration in the mid-1990s bordered on depression. A coach now, he hopes to protect his wards from what he went through.

Cricket is also unique among team sports because of the clout the captain or the coach enjoys. In football, basketball or rugby, a player’s talent can’t be hidden, despite any level of scheming. "If the captain doesn’t like you, he can restrict you to a short bowling spell, or ask you to bowl when the batsmen are completely set, or to bowl only against the wind," says a former Delhi junior player. And heard of this? A Delhi cricket official whose son is a left-arm spinner managed to get all his counterparts dropped from the junior teams. The reason: so that there’s no competition for his son when he’s old enough to play first-class cricket. Then there are the debilitating injuries that nip the careers of hundreds of hopefuls.

All this, naturally, begets cynicism and frustration—always a close ally to depression.Many give up the game to brood indoors, cursing their fate or the system. Like Sumit Kundu, 21, for whom cricket was life for 10 long years. He was captain of the Haryana under-17 team, but in 2007, when he was preparing for the state’s under-19 team, he was told he was not good enough. Kundu slipped into depression. "I stopped going out with friends, used to cry for hours," he says. Kundu was wise enough to relinquish his dream early, providing him time to prepare for an MBA course. "I’ll never go back to cricket again. It’s too painful," he says.

Suhail Sharma, 26, Delhi

Couldn’t cement his place in the Ranji team. Went through torrid times for two years. "I feared I’d have to give up cricket and work crazy shifts like some of my friends, who start work at 4 am to oversee newspaper distribution, with no time for cricket," he says. A job with ONGC helped.

Outlook cited a few of these cases to Nimesh G. Desai, head of the Institute of Human Behaviour and Allied Sciences in Delhi. He confirms that the symptoms do indicate depression, but adds that no study has been done to gauge the incidence of depression among cricketers specifically. He also explained why the impact of failure in cricket is more severe than in other fields of human endeavour: "In cricket, as also in the movie industry, the stakes are very high, expectations are high, and there’s a high degree of emotional and physical investment. At stake is a high degree of social adulation, or retribution for that matter."

"In cricket, the stakes are very high as are expectations. There's a high degree of emotional, physical investment."

Often, budding cricketers chase their dreams till the very end, unable to read the writing on the wall. Some, like Vinayak Samant, 36, have managed to survive the trauma. From a lower middle-class family from the Mumbai suburb of Virar, this gritty wicketkeeper-batsman had had his share of lows—but never slipped into the darkness of depression. It’s only now, after 20 years of hoping, that he’s reconciled to his shattered dream of playing for India. Former India opener Aakash Chopra, who’s no stranger to disappointment, told Outlook, "Young players have big dreams, sometimes you are not good enough, other times you realise you need more than just performance on the field. You get selected 10 times and are then suddenly dropped for no obvious reason. You see yourself as a failure. Players, even at the first-class level, live gloomy lives, away from the glamour and money associated with cricket."

Sadanand Viswanath, 46, India

A rising superstar in early 1985, dropped from the team the same year. His father committed suicide; mother died soon after. He went "over the limit" with alcohol. A qualified umpire now, he says "too much expectation at a young age leads to disaster. Better to have delayed gratification".

In a sense, the Indian Premier League (IPL) is a welcome development for the forgotten, poor men of Indian cricket, for it has opened up new avenues for them. "It’s a boon," agrees Chopra. "First-class level players have worked very, very hard to reach where they are. Now more of them can make a better living from the game."

To succeed at the top, youngsters need endless passion, ambition and absolute confidence. For doubt is fatal.

But most are doomed to suffer in the shadows. Maninder Singh, a prodigy who faded away, says it would help if the coaches were honest with the parents."The coach’s conscience has to be clean and pure," he told Outlook. "They must be honest with a player, ask him to focus on studies if he has little talent or no future in the game." Adds Arun Lal, "Disappointment is guaranteed. Success is not. Once that is established, depression cannot defeat you. Cricket can never be a career prospect. It should be a passion and if it happens to become a career one day, great! But don’t count on it."

For the young players, the algebra for success is baffling: to succeed at the top, they need endless passion, ambition and absolute confidence. For doubt is fatal. This must be accompanied by maturity, for disappointments must and will buffet them at every step. It’s a very rare blend that succeeds, most don’t have it in them. All the more reason why parents must prepare their children for heartbreak...and a career in other fields.