“Blessed is the nation that doesn’t need heroes" Goethe. “Hero-worship is strongest where there is least regard for human freedom.” Herbert Spencer. "My 80% friend isn't my 20% enemy" Ronald Reagan.

Search This Blog

Tuesday 19 March 2019

The best form of self-help is … a healthy dose of unhappiness

We’re seeking solace in greater numbers than ever. But we’re more likely to find it in reality than in positive thinking writes Tim Lott in The Guardian

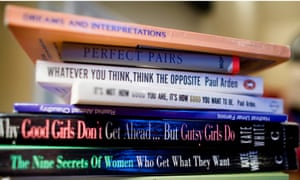

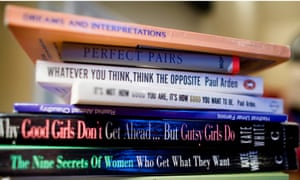

‘Self-help is almost as broad a genre as fiction.’ Photograph: Christopher Thomond/The Guardian

Booksellers have announced that sales of self-help books are at record levels. The cynics out there will sigh deeply in resignation, even though I suspect they don’t really have a clear idea of what a self-help book is (or could be). Then again, no one has much of an idea what a self-help book is. Is it popular psychology (such as Blink, or Daring Greatly)? Is it spirituality (The Power of Now, or A Course in Miracles)? Or a combination of both (The Road Less Travelled)?

Is it about “success” (The Seven Secrets of Successful People) or accumulating money (Mindful Money, or Think and Grow Rich)? Is Caitlin Moran’s How to Be a Woman self-help? Or the Essays of Montaigne?

Self-help – although I would prefer the term “self-curiosity” – is almost as broad a genre as fiction. Just as there are a lot of turkeys in literature, there are plenty in the self-help section, some of them remarkably successful despite – or because of – their idiocy. My personal nominations for the closest tosh-to-success correlation would include The Secret, You Can Heal Your Life and The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up – but that is narrowing down a very wide field.

In the minority are the intelligent and worthwhile books – but they can be found. I have enjoyed so-called pop psychology and spirituality books ever since I discovered Families and How to Survive Them by John Cleese and Robin Skynner in the 1980s, and Depression: The Way out of Your Prison by Dorothy Rowe at around the same time.

The Cleese book is a bit dated now, but Rowe’s set me off on a road that I am still following. She is what you might call a non-conforming Buddhist who introduced me to the writing of Alan Watts ( another non-conformer) whose The Meaning of Happiness and The Book have informed my life and worldview ever since.

The irony is that books of this particular stripe point you in a direction almost the opposite of most self-help books. Because, from How to Win Friends and Influence People through to The Power of Positive Thinking and Who Moved My Cheese?, “positive thinking” seems to be the unifying principle (although now partially supplanted by “mindfulness”).

The books I draw sustenance from contain the opposite wisdom. This isn’t negativity. It’s acceptance. Such thinking does not at first glance point you towards the destination of a happier life, which is probably why such tomes are far less popular than their bestselling peers. Yet these counter self-help books have a remarkable amount in common.

Most of them have Buddhism or Stoicism underpinning their thoughts. And they offer a different, and perhaps harder, road to happiness: not through effort, or willpower, or struggle with yourself, but through the forthright facing of facts that most of us prefer not to accept or think about.

Whether Seneca, or Nietzsche, Viktor Frankl or Rowe, Watts or Oliver Burkeman (The Antidote), or most recently Jordan B Peterson (12 Rules for Life), these thinkers all say much the same thing. Stop pretending. Get real.

It is not easy advice. Reality – now as ever – is unpopular, and for good reason. But the great thing about these self-help books is that, while giving sound advice, they are clear-eyed in acknowledging the truth: that happiness is not a given for anyone, there is no magic way of getting “it” – and that, crucially, pursuing it (or even believing in it), is one of the biggest obstacles to actually receiving it.

Such writers suggest the radical path to happiness comes from recognising the inevitability of unhappiness that comes as a result of the human birthright, that is, randomness, mortality, transitoriness, uncertainty and injustice. In other words, all the things we naturally shy away from and spend a huge amount of time and painful mental effort denying or trying not to think about.

Peterson perhaps puts it too strongly to say “life is catastrophe”, and the Buddha is out of date with “life is suffering”. Such strong medicine is understandably hard to take for many people in the comfortable and pleasure-seeking west. And despite what both Peterson and the Buddha say, not everyone suffers all that much.

Some people are just born happy or are lucky, or both, and are either incapable of feeling, or fortunate enough to never to have felt, a great deal in the way of pain or trauma. They are the people who never buy self-help books. But such individuals, I would suggest (although I can’t prove it), are the exception rather than the rule. The rest of us are simply pretending, to ourselves and to others, in order not to feel like failures.

But unhappiness is not failure. It is not pessimistic or morbid to say, for most of us, that life can be hard and that conflict is intrinsic to being and that mortality shadows our waking hours.

In fact it is life-affirming – because once you stop displacing these fears into everyday neuroses, life becomes tranquil, even when it is painful. And during those difficult times of loss and pain, to assert “this is the mixed package called life, and I embrace it in all its positive and negative aspects” shows real courage, rather than hiding in flickering, insubstantial fantasies of control, mysticism, virtue or wishful thinking.

That, as Dorothy Rowe says, is the real secret – that there is no secret.

Booksellers have announced that sales of self-help books are at record levels. The cynics out there will sigh deeply in resignation, even though I suspect they don’t really have a clear idea of what a self-help book is (or could be). Then again, no one has much of an idea what a self-help book is. Is it popular psychology (such as Blink, or Daring Greatly)? Is it spirituality (The Power of Now, or A Course in Miracles)? Or a combination of both (The Road Less Travelled)?

Is it about “success” (The Seven Secrets of Successful People) or accumulating money (Mindful Money, or Think and Grow Rich)? Is Caitlin Moran’s How to Be a Woman self-help? Or the Essays of Montaigne?

Self-help – although I would prefer the term “self-curiosity” – is almost as broad a genre as fiction. Just as there are a lot of turkeys in literature, there are plenty in the self-help section, some of them remarkably successful despite – or because of – their idiocy. My personal nominations for the closest tosh-to-success correlation would include The Secret, You Can Heal Your Life and The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up – but that is narrowing down a very wide field.

In the minority are the intelligent and worthwhile books – but they can be found. I have enjoyed so-called pop psychology and spirituality books ever since I discovered Families and How to Survive Them by John Cleese and Robin Skynner in the 1980s, and Depression: The Way out of Your Prison by Dorothy Rowe at around the same time.

The Cleese book is a bit dated now, but Rowe’s set me off on a road that I am still following. She is what you might call a non-conforming Buddhist who introduced me to the writing of Alan Watts ( another non-conformer) whose The Meaning of Happiness and The Book have informed my life and worldview ever since.

The irony is that books of this particular stripe point you in a direction almost the opposite of most self-help books. Because, from How to Win Friends and Influence People through to The Power of Positive Thinking and Who Moved My Cheese?, “positive thinking” seems to be the unifying principle (although now partially supplanted by “mindfulness”).

The books I draw sustenance from contain the opposite wisdom. This isn’t negativity. It’s acceptance. Such thinking does not at first glance point you towards the destination of a happier life, which is probably why such tomes are far less popular than their bestselling peers. Yet these counter self-help books have a remarkable amount in common.

Most of them have Buddhism or Stoicism underpinning their thoughts. And they offer a different, and perhaps harder, road to happiness: not through effort, or willpower, or struggle with yourself, but through the forthright facing of facts that most of us prefer not to accept or think about.

Whether Seneca, or Nietzsche, Viktor Frankl or Rowe, Watts or Oliver Burkeman (The Antidote), or most recently Jordan B Peterson (12 Rules for Life), these thinkers all say much the same thing. Stop pretending. Get real.

It is not easy advice. Reality – now as ever – is unpopular, and for good reason. But the great thing about these self-help books is that, while giving sound advice, they are clear-eyed in acknowledging the truth: that happiness is not a given for anyone, there is no magic way of getting “it” – and that, crucially, pursuing it (or even believing in it), is one of the biggest obstacles to actually receiving it.

Such writers suggest the radical path to happiness comes from recognising the inevitability of unhappiness that comes as a result of the human birthright, that is, randomness, mortality, transitoriness, uncertainty and injustice. In other words, all the things we naturally shy away from and spend a huge amount of time and painful mental effort denying or trying not to think about.

Peterson perhaps puts it too strongly to say “life is catastrophe”, and the Buddha is out of date with “life is suffering”. Such strong medicine is understandably hard to take for many people in the comfortable and pleasure-seeking west. And despite what both Peterson and the Buddha say, not everyone suffers all that much.

Some people are just born happy or are lucky, or both, and are either incapable of feeling, or fortunate enough to never to have felt, a great deal in the way of pain or trauma. They are the people who never buy self-help books. But such individuals, I would suggest (although I can’t prove it), are the exception rather than the rule. The rest of us are simply pretending, to ourselves and to others, in order not to feel like failures.

But unhappiness is not failure. It is not pessimistic or morbid to say, for most of us, that life can be hard and that conflict is intrinsic to being and that mortality shadows our waking hours.

In fact it is life-affirming – because once you stop displacing these fears into everyday neuroses, life becomes tranquil, even when it is painful. And during those difficult times of loss and pain, to assert “this is the mixed package called life, and I embrace it in all its positive and negative aspects” shows real courage, rather than hiding in flickering, insubstantial fantasies of control, mysticism, virtue or wishful thinking.

That, as Dorothy Rowe says, is the real secret – that there is no secret.

Sunday 17 March 2019

Why we should be honest about failure

Disappointment is the natural order of life. Most people achieve less than they would like writes JANAN GANESH in The FT

On a long-haul flight, Can You Ever Forgive Me? becomes the first film I have ever watched twice in immediate succession. Released last month in Britain, it recounts the (true) story of Lee Israel, a once-admired, now-marginal writer who resorts to literary forgery to make the rent on her fetid New York hovel. Her one friend is himself a washout who, as per the English tradition, passes off his insolvency as bohemia. Lee pleads with her agent to answer her calls and, in the rawest scene, confesses her crime with a wistful pang for the success it brought her.

There are serviceable jokes (including the profane farewell between the two friends) but the film is ultimately about failure: social, financial, romantic, professional. Put it down to the lachrymose effects of air travel — a phenomenon that has no definitive explanation — but I found the film unusually affecting. Or perhaps it was the shock of seeing failure addressed so unsentimentally, and from so many angles.

Failure — not spectacular failure, but failure as gnawing disappointment — is the natural order of life. Most people will achieve at least a little bit less than they would have liked in their careers. Most marriages wind down from intense passion to a kind of elevated friendship, and even this does not count the roughly four in 10 that collapse entirely. Most businesses fail. Most books fail. Most films fail.

You would hope that something so endemic to the human experience would be constantly discussed and actively prepared for. Instead, what we hear about is failure as a great “teacher”, or as a staging post before eventual success. There are management books about “failing forward”. There are educational methods that teach children the uses of failure. Consult an anthology of quotations about the subject, and it is not just the Paulo Coelho types who sugar-coat it. Churchill, Edison, Capote, at least one Roosevelt: people who should know better almost deny the existence of failure as anything other than a character-building phase.

There are good intentions behind all this. There is also a lot of naivety and squeamishness. For many people, failure will be just that, not a nourishing experience or a bridge to something else. It will be a lasting condition, and it will sting a fair bit.

Our seeming inability to look this fact in the eye is not just unbecoming in and of itself, it also inadvertently makes the experience of failure more harrowing than it needs to be. By reimagining it as just a holding pen before ultimate triumph, those who find themselves stuck there must feel like aberrations, when their experience could not be more banal.

I have known lots of Lee Israels: sensations at 25, under-achievers at 40. Sometimes, there was an identifiable wrong turn — a duff career move, say, or the pram in the hallway. But in most cases, it was just the law of numbers doing its impersonal work.

In almost all professions, there are too few places at the top for too many hopefuls. Lots of blameless people will miss out. Whether at school or through those excruciating management guides, a wiser culture would not romanticise failure as a means to success. It would normalise it as an end.

Look again at that list of names who have minted smarmy epigrams about the utility of failure. It is, you realise, a kind of winner’s wisdom. Those who overcome setbacks to achieve epic feats tend to universalise their atypical experience. Amazingly bad givers of advice, they encourage people to proceed with ambitions that are best sat on, and despise “quitters” when quitting is often the purest common sense.

At the end of Can You Ever Forgive Me?, Lee is an unambiguous failure. There is (and you will excuse the spoilers) no rapprochement with an ex-lover she is plainly not over. There is no conquest of her drink habit. The film could dwell on the real-life Lee’s successful memoir, on which it is based, but only mentions it in text as the screen goes dark. She loses her solitary friend to illness. Even the cat croaks. Why, then, is the film so moreish as to demand an instant repeat over the Atlantic? It is, I think, the honest ventilation of a universal human subject. It is the novelty of being treated as a grown-up.

On a long-haul flight, Can You Ever Forgive Me? becomes the first film I have ever watched twice in immediate succession. Released last month in Britain, it recounts the (true) story of Lee Israel, a once-admired, now-marginal writer who resorts to literary forgery to make the rent on her fetid New York hovel. Her one friend is himself a washout who, as per the English tradition, passes off his insolvency as bohemia. Lee pleads with her agent to answer her calls and, in the rawest scene, confesses her crime with a wistful pang for the success it brought her.

There are serviceable jokes (including the profane farewell between the two friends) but the film is ultimately about failure: social, financial, romantic, professional. Put it down to the lachrymose effects of air travel — a phenomenon that has no definitive explanation — but I found the film unusually affecting. Or perhaps it was the shock of seeing failure addressed so unsentimentally, and from so many angles.

Failure — not spectacular failure, but failure as gnawing disappointment — is the natural order of life. Most people will achieve at least a little bit less than they would have liked in their careers. Most marriages wind down from intense passion to a kind of elevated friendship, and even this does not count the roughly four in 10 that collapse entirely. Most businesses fail. Most books fail. Most films fail.

You would hope that something so endemic to the human experience would be constantly discussed and actively prepared for. Instead, what we hear about is failure as a great “teacher”, or as a staging post before eventual success. There are management books about “failing forward”. There are educational methods that teach children the uses of failure. Consult an anthology of quotations about the subject, and it is not just the Paulo Coelho types who sugar-coat it. Churchill, Edison, Capote, at least one Roosevelt: people who should know better almost deny the existence of failure as anything other than a character-building phase.

There are good intentions behind all this. There is also a lot of naivety and squeamishness. For many people, failure will be just that, not a nourishing experience or a bridge to something else. It will be a lasting condition, and it will sting a fair bit.

Our seeming inability to look this fact in the eye is not just unbecoming in and of itself, it also inadvertently makes the experience of failure more harrowing than it needs to be. By reimagining it as just a holding pen before ultimate triumph, those who find themselves stuck there must feel like aberrations, when their experience could not be more banal.

I have known lots of Lee Israels: sensations at 25, under-achievers at 40. Sometimes, there was an identifiable wrong turn — a duff career move, say, or the pram in the hallway. But in most cases, it was just the law of numbers doing its impersonal work.

In almost all professions, there are too few places at the top for too many hopefuls. Lots of blameless people will miss out. Whether at school or through those excruciating management guides, a wiser culture would not romanticise failure as a means to success. It would normalise it as an end.

Look again at that list of names who have minted smarmy epigrams about the utility of failure. It is, you realise, a kind of winner’s wisdom. Those who overcome setbacks to achieve epic feats tend to universalise their atypical experience. Amazingly bad givers of advice, they encourage people to proceed with ambitions that are best sat on, and despise “quitters” when quitting is often the purest common sense.

At the end of Can You Ever Forgive Me?, Lee is an unambiguous failure. There is (and you will excuse the spoilers) no rapprochement with an ex-lover she is plainly not over. There is no conquest of her drink habit. The film could dwell on the real-life Lee’s successful memoir, on which it is based, but only mentions it in text as the screen goes dark. She loses her solitary friend to illness. Even the cat croaks. Why, then, is the film so moreish as to demand an instant repeat over the Atlantic? It is, I think, the honest ventilation of a universal human subject. It is the novelty of being treated as a grown-up.

Americans really pay a bribe for a good education? In Britain, we’ve got far subtler ways

The deviousness that some routinely resort to here puts the US scandal in the shade writes Catherine Bennett in The Guardian

Actress Felicity Huffman has been indicted in the university admissions scandal. Photograph: David McNew/AFP/Getty Images

Ditto Smith’s generous quotation from a statement provided for a girl who has been reinvented, apparently for scam purposes, as a “US Club Soccer All American”: “On the soccer or lacrosse etc I am the one who looks like a boy amongst girls with my hair tied up, arms sleeveless, and blood and bruises from head to toe.”

Not, of course, that’s there’s anything illegal, here or in the US, about reproducing personal statements from professional suppliers or collaborating with a teacher and/or parent – the latter, though risibly unfair, is routine. Another Varsity Blues alleged tactic, that of buying a diagnosis requiring extra exam time, may have no exact UK parallel but, according to a 2017 BBC report, one in five children in independent schools received extra time for GCSE and A-levels. David Kynaston and David Green, in a powerful critique of independent schools, recently pointed out various advantages, made possible by high fees: “Far greater resources are available for diagnosing special needs, challenging exam results and guiding university applications.”

If, mercifully, UK universities are low on dependable side doors, the shamelessness of some of the US defendants, as they appear to pursue their imagined birthright (Ivy League bragging rights) can still sound uncomfortably familiar. Many British parents, equally fearful of mediocrity, are similarly unabashed on local tricks and stratagems – not only private education, but house moves, music lessons (for reserved school places), intensive coaching, internships, resits, religious conversions, fake addresses, and, the Times now reports, FOI requests to Oxbridge, from disappointed parents – that will end up, added to financial and cultural capital, delivering much the same outcome as the US scandal. Legal or otherwise, the result is enhanced educational opportunities for the privileged and untalented, fewer for the talented but disadvantaged.

The pervasive cunning is hardly surprising given the official esteem for “sharp-elbowed” parental operators, who, David Laws once argued, set a fine example. It follows, as demonstrated by UK politicians on all sides, that extreme resourcefulness in, say, keeping places from less fortunate residents, is readily passed off as understandable dedication as opposed to insatiable self-interest. Don’t we all want [smiling face with halo emoji] the best for our kids?

Following some unspecified epiphany, David Cameron, of previously wavering faith, secured places at an oversubscribed church school, some distance from No 10, requiring proof of “Sunday worship in a church at least twice a month for 36 months before the closing applications date”. Equally instructively, my own, affluent MP, Emily Thornberry, had, earlier, hoovered up three of the few precious places at an outstanding, part-selective school in Hertfordshire, 13 miles from home, which tradition annually reserves for her Islington constituents. On Twitter, she has reminded critics: “All my children educated in the state sector.” There is no suggestion that either MP has broken any laws.

There must be, beyond legality, some ethically significant factor that makes non-paying wangling infinitely superior to the ugly, US variety. But you probably have to buy a place at Harvard to find out what it is.

‘Emily Thornberry hoovered up three precious places at an outstanding part-selective school.’ Photograph: George Cracknell Wright/Rex/Shutterstock

“Dude, dude, what do you think, I’m a moron?” Thus, one of the parents accused of involvement in the US college bribery racket. He’d been warned – by a wiretapped conspirator – not to reveal that he paid $50,000 for his daughter’s fraudulent test results, part of a system the fixer calls “the side door”.

Appropriately soothed – “I’m not saying you’re a moron” – the accused father is recorded, by the FBI, assuring the scam’s organiser that he’ll deliver, if required, the agreed fiction. “I’m going to say that I’ve been inspired how you’re helping underprivileged kids get into college. Totally got it.”

Although many of the best bits of an FBI affidavit – presenting the case against the accused parents – have been widely circulated, this sublime page-turner deserves to be enjoyed in full, if not put up for literary awards pending film adaptation (Laura Dern has been suggested for Felicity Huffman), and made compulsory reading in all admission departments. It’s not just that extracts can’t convey the fathomless entitlement and mendacity exhibited by affluent, ostensibly respectable parents. They can’t begin to do justice to the affidavit’s entertainment value as savage social comedy, something productions of Molière often attempt, but rarely achieve.

Even the dramatis personae, in the investigation the FBI named “Operation Varsity Blues”, reads like an updated Tartuffe: “Todd Blake is an entrepreneur and investor. Diane Blake is an executive at a retail merchandising firm.” Here, too, cultivated, fluent people, many of whom also sound deluded, greedy and hypocritical, appear to be playing with their children’s lives for no reason beyond self-gratification. But the dialogue, when not jaw-dropping, races along (“And it works?” asks a defendant. “Every time.”), the plots and motives are horribly plausible, and the jeopardy is evidently real to the alleged conspirators, even if the all-encompassing irony of their alleged scheme is not. “She actually won’t really be part of the water polo team, right?”

And from a fellow future defendant, on the risks, if this status-enhancing, child-perfecting scam were to be discovered: “You know, the, the embarrassment to everyone in the communities. Oh my God, it would just be – yeah. Ugh.”

Are FBI affidavits regularly as good as the tale of Operation Varsity Blues? If so, the death of the novel should be easier to bear. Although this document has one overriding purpose – to show that accused parents and witnesses colluded in fraudulent applications – special thanks are due to special agent Laura Smith, the author, who never writes a dull page. Maybe the individual cases were fully as compelling as this edited evidence suggests. Or maybe agent Smith’s organisation of her material really does indicate considerable, dry artistry? Either way, you cherish the detail when an accused parent replies, following an allegedly fraudulently extracted college offer: “This is wonderful news! [high-five emoji].”

“Dude, dude, what do you think, I’m a moron?” Thus, one of the parents accused of involvement in the US college bribery racket. He’d been warned – by a wiretapped conspirator – not to reveal that he paid $50,000 for his daughter’s fraudulent test results, part of a system the fixer calls “the side door”.

Appropriately soothed – “I’m not saying you’re a moron” – the accused father is recorded, by the FBI, assuring the scam’s organiser that he’ll deliver, if required, the agreed fiction. “I’m going to say that I’ve been inspired how you’re helping underprivileged kids get into college. Totally got it.”

Although many of the best bits of an FBI affidavit – presenting the case against the accused parents – have been widely circulated, this sublime page-turner deserves to be enjoyed in full, if not put up for literary awards pending film adaptation (Laura Dern has been suggested for Felicity Huffman), and made compulsory reading in all admission departments. It’s not just that extracts can’t convey the fathomless entitlement and mendacity exhibited by affluent, ostensibly respectable parents. They can’t begin to do justice to the affidavit’s entertainment value as savage social comedy, something productions of Molière often attempt, but rarely achieve.

Even the dramatis personae, in the investigation the FBI named “Operation Varsity Blues”, reads like an updated Tartuffe: “Todd Blake is an entrepreneur and investor. Diane Blake is an executive at a retail merchandising firm.” Here, too, cultivated, fluent people, many of whom also sound deluded, greedy and hypocritical, appear to be playing with their children’s lives for no reason beyond self-gratification. But the dialogue, when not jaw-dropping, races along (“And it works?” asks a defendant. “Every time.”), the plots and motives are horribly plausible, and the jeopardy is evidently real to the alleged conspirators, even if the all-encompassing irony of their alleged scheme is not. “She actually won’t really be part of the water polo team, right?”

And from a fellow future defendant, on the risks, if this status-enhancing, child-perfecting scam were to be discovered: “You know, the, the embarrassment to everyone in the communities. Oh my God, it would just be – yeah. Ugh.”

Are FBI affidavits regularly as good as the tale of Operation Varsity Blues? If so, the death of the novel should be easier to bear. Although this document has one overriding purpose – to show that accused parents and witnesses colluded in fraudulent applications – special thanks are due to special agent Laura Smith, the author, who never writes a dull page. Maybe the individual cases were fully as compelling as this edited evidence suggests. Or maybe agent Smith’s organisation of her material really does indicate considerable, dry artistry? Either way, you cherish the detail when an accused parent replies, following an allegedly fraudulently extracted college offer: “This is wonderful news! [high-five emoji].”

Actress Felicity Huffman has been indicted in the university admissions scandal. Photograph: David McNew/AFP/Getty Images

Ditto Smith’s generous quotation from a statement provided for a girl who has been reinvented, apparently for scam purposes, as a “US Club Soccer All American”: “On the soccer or lacrosse etc I am the one who looks like a boy amongst girls with my hair tied up, arms sleeveless, and blood and bruises from head to toe.”

Not, of course, that’s there’s anything illegal, here or in the US, about reproducing personal statements from professional suppliers or collaborating with a teacher and/or parent – the latter, though risibly unfair, is routine. Another Varsity Blues alleged tactic, that of buying a diagnosis requiring extra exam time, may have no exact UK parallel but, according to a 2017 BBC report, one in five children in independent schools received extra time for GCSE and A-levels. David Kynaston and David Green, in a powerful critique of independent schools, recently pointed out various advantages, made possible by high fees: “Far greater resources are available for diagnosing special needs, challenging exam results and guiding university applications.”

If, mercifully, UK universities are low on dependable side doors, the shamelessness of some of the US defendants, as they appear to pursue their imagined birthright (Ivy League bragging rights) can still sound uncomfortably familiar. Many British parents, equally fearful of mediocrity, are similarly unabashed on local tricks and stratagems – not only private education, but house moves, music lessons (for reserved school places), intensive coaching, internships, resits, religious conversions, fake addresses, and, the Times now reports, FOI requests to Oxbridge, from disappointed parents – that will end up, added to financial and cultural capital, delivering much the same outcome as the US scandal. Legal or otherwise, the result is enhanced educational opportunities for the privileged and untalented, fewer for the talented but disadvantaged.

The pervasive cunning is hardly surprising given the official esteem for “sharp-elbowed” parental operators, who, David Laws once argued, set a fine example. It follows, as demonstrated by UK politicians on all sides, that extreme resourcefulness in, say, keeping places from less fortunate residents, is readily passed off as understandable dedication as opposed to insatiable self-interest. Don’t we all want [smiling face with halo emoji] the best for our kids?

Following some unspecified epiphany, David Cameron, of previously wavering faith, secured places at an oversubscribed church school, some distance from No 10, requiring proof of “Sunday worship in a church at least twice a month for 36 months before the closing applications date”. Equally instructively, my own, affluent MP, Emily Thornberry, had, earlier, hoovered up three of the few precious places at an outstanding, part-selective school in Hertfordshire, 13 miles from home, which tradition annually reserves for her Islington constituents. On Twitter, she has reminded critics: “All my children educated in the state sector.” There is no suggestion that either MP has broken any laws.

There must be, beyond legality, some ethically significant factor that makes non-paying wangling infinitely superior to the ugly, US variety. But you probably have to buy a place at Harvard to find out what it is.

Saturday 16 March 2019

Be honest, be kind: five lessons from an amicable divorce

Consciously uncoupling is possible: choose your battles, build a support network and learn to play the long game writes Kate Gunn in The Guardian

1 Understand that marriage breakdown impacts on everyone – yes, even your ex

The first night after telling the children that their father I were splitting up, I lay awake in bed with all three of them curled around me asking endless questions: “What is happening?” “Why don’t you love each other?” “Do you still love me?” “Where will Daddy live?” “Why does it hurt so much?”

I stared out into the darkness, praying for sleep. But I also thought of Kristian, alone in a different bed in another part of the house. He didn’t have the comfort of the children, yet he was fighting his own demons. It was an important step for me to take. It wasn’t just me and the children suffering – Kristian was, too. We were in this together, even if we were parting.

Our new living arrangements meant that I had the children most of the time. As the months went on, Kristian admitted that he understood the impact this had on me. He knew it wasn’t easy. Just hearing him say it eased the burden and any resentment that may have built up.

Never lose sight of the fact that the breakdown of a marriage affects everyone involved – not just you. It’s the key to having the compassion to get through it together.

2 Gather a positive support network

Support was vital in the early stages, and we were both lucky to have family who picked us up and carried us. Once the mantra of “I’m fine” was dispensed with, and we accepted the offers of help, our support network became a hugely positive influence on how the breakup manifested itself.

My sisters would check in on Kristian regularly, and his parents would message to see how I was getting on. There was neither blame nor accusations from either side, and everyone was prepared to help us and the children through the most difficult times.

I have spoken to others who have been through separation or divorce, many of whom said those closest to them wanted to show support by pointing fingers. That kind of behaviour makes the vital task of building a good relationship with your former partner much more difficult. Make it clear that you aren’t looking to play the blame game and that it’s far better for everyone if other voices are supportive but balanced. If they are unable to do that, gently ask them to take a step back until you are in a more stable place.

3 Always aim for the middle

Think about which aspects you want lawyers to be involved in. Although we took advantage of a free mediation service run by the Legal Aid Board (we live in Ireland, but there will be a service wherever you live), we did a lot of the early negotiating ourselves: living arrangements, care of the children, who got the coveted CD collection. This kept legal costs and interference down. We both knew that if lawyers got involved in the early negotiations it would not only become expensive, but probably more contentious, too. Legal representatives will usually fight for their client’s right to as much as possible – that is, after all, what you are paying them for. But we didn’t want to fight. We wanted what was fair.

Our starting point was that we wanted the children to be happy and we wanted each other to be happy; we tried to make decisions based on these factors. The only thing that always seemed to throw us off track was money.

I would wake frequently at night, numbers swirling around my head – the moving bills, the double rent, the extra light, heat, car and petrol costs that would need to be paid for out of a very limited and stagnant pool of money. No matter which way I spun them, the numbers never balanced out.

Kristian and I discussed what we could do to improve our financial situation. He offered to take the kids for another night during the week so I could take on extra work. We negotiated until we reached a mid-point agreement that neither of us was entirely happy with. In hindsight, this was probably a good indication that it was pretty fair.

Try to work out what you absolutely need legal advice on and what you can sort out between yourselves. If you get 80% of an agreement in place together, it will be a lot less stressful and expensive to get the remaining 20% finalised with legal assistance.

4 Play the long game

The early months of separation are often when things go awry. With so much fear and uncertainty, it’s like a game of Hungry Hippos, with each of you blindly grabbing as much as you can, as quickly as you can, afraid to lose out on anything, whether you want it or not.

When people ask me for advice, I tell them what I was told by others: “Play the long game.” Don’t look for the small wins that will make this day, or this week, or even this year easier. Look at the long-term goal. What’s important to you?

For us, it was our relationship and our children’s happiness. We placed a good relationship between ourselves above long-term financial security. For me, fighting for extra child maintenance each month at the expense of Kristian’s living arrangements didn’t seem like a solid long-term plan. I might have gained an extra bedroom, but for a lifetime of animosity it was never going to be worth it. In turn, Kristian placed being close to the children above his desire to run home to friends and family.

Choose your battles. Don’t fight for what you can get or what you have been told to expect – work out what you really want and how it will affect the relationship with your ex-partner for the next 20 years.

5 Write, don’t speak

Things didn’t always run smoothly, of course. There were arguments and fallouts, and some moments when I thought the wheels had entirely fallen off. In the most difficult times we often communicated best by email. It allowed us to consider what we wanted to say and then let the other person digest the words in their own time. During one particularly fraught discussion about money, Kristian sent me an email that was so beautifully written and so perfectly timed that I could say it saved our entire breakup.

Here’s a part of it: “I would like to believe we have the trust, integrity and maturity to deal with this in the right manner. I know you. I know you are not manipulative, nor selfish, nor deceitful. Our kids are a beautiful testament to both of us being honest, loving, loyal and all round beautiful people! I want us to remain great friends, not because of our kids, but because of all the great experiences we have encountered together and the growth through them.”

That email contained all the lessons any couple need for a good divorce: honesty, explanation, compassion and compromise.

Kate Gunn and ex-husband Kristian. Photograph: Cliona O'Flaherty/The Guardian

It’s not always infidelity that leads a couple to split – sometimes a marriage simply runs out of steam and both sides are better off apart. But when that happens, is it really possible to part amicably?

It’s been five years since my marriage broke down but, since Kristian and I separated, we have been on family holidays together, shared dinners, spent every Christmas with one another and even been out to a gig while my new partner babysat.

It was hard to disentangle our lives when we had three kids, a house, friends, family, debts, savings, personal possessions, plus 10 years of shared memories, but we did it and remained friends. How was that possible?

The secret was that those five years of untangling our lives weren’t just about the nuts and bolts of separation and divorce – they were about building up a new friendship, too. It may seem extreme to talk about friendship in the same breath as divorce but, while it wasn’t easy, by remaining friends, life is now so much better for all of us.

Here are my five lessons for consciously uncoupling in the real world.

It’s not always infidelity that leads a couple to split – sometimes a marriage simply runs out of steam and both sides are better off apart. But when that happens, is it really possible to part amicably?

It’s been five years since my marriage broke down but, since Kristian and I separated, we have been on family holidays together, shared dinners, spent every Christmas with one another and even been out to a gig while my new partner babysat.

It was hard to disentangle our lives when we had three kids, a house, friends, family, debts, savings, personal possessions, plus 10 years of shared memories, but we did it and remained friends. How was that possible?

The secret was that those five years of untangling our lives weren’t just about the nuts and bolts of separation and divorce – they were about building up a new friendship, too. It may seem extreme to talk about friendship in the same breath as divorce but, while it wasn’t easy, by remaining friends, life is now so much better for all of us.

Here are my five lessons for consciously uncoupling in the real world.

1 Understand that marriage breakdown impacts on everyone – yes, even your ex

The first night after telling the children that their father I were splitting up, I lay awake in bed with all three of them curled around me asking endless questions: “What is happening?” “Why don’t you love each other?” “Do you still love me?” “Where will Daddy live?” “Why does it hurt so much?”

I stared out into the darkness, praying for sleep. But I also thought of Kristian, alone in a different bed in another part of the house. He didn’t have the comfort of the children, yet he was fighting his own demons. It was an important step for me to take. It wasn’t just me and the children suffering – Kristian was, too. We were in this together, even if we were parting.

Our new living arrangements meant that I had the children most of the time. As the months went on, Kristian admitted that he understood the impact this had on me. He knew it wasn’t easy. Just hearing him say it eased the burden and any resentment that may have built up.

Never lose sight of the fact that the breakdown of a marriage affects everyone involved – not just you. It’s the key to having the compassion to get through it together.

2 Gather a positive support network

Support was vital in the early stages, and we were both lucky to have family who picked us up and carried us. Once the mantra of “I’m fine” was dispensed with, and we accepted the offers of help, our support network became a hugely positive influence on how the breakup manifested itself.

My sisters would check in on Kristian regularly, and his parents would message to see how I was getting on. There was neither blame nor accusations from either side, and everyone was prepared to help us and the children through the most difficult times.

I have spoken to others who have been through separation or divorce, many of whom said those closest to them wanted to show support by pointing fingers. That kind of behaviour makes the vital task of building a good relationship with your former partner much more difficult. Make it clear that you aren’t looking to play the blame game and that it’s far better for everyone if other voices are supportive but balanced. If they are unable to do that, gently ask them to take a step back until you are in a more stable place.

3 Always aim for the middle

Think about which aspects you want lawyers to be involved in. Although we took advantage of a free mediation service run by the Legal Aid Board (we live in Ireland, but there will be a service wherever you live), we did a lot of the early negotiating ourselves: living arrangements, care of the children, who got the coveted CD collection. This kept legal costs and interference down. We both knew that if lawyers got involved in the early negotiations it would not only become expensive, but probably more contentious, too. Legal representatives will usually fight for their client’s right to as much as possible – that is, after all, what you are paying them for. But we didn’t want to fight. We wanted what was fair.

Our starting point was that we wanted the children to be happy and we wanted each other to be happy; we tried to make decisions based on these factors. The only thing that always seemed to throw us off track was money.

I would wake frequently at night, numbers swirling around my head – the moving bills, the double rent, the extra light, heat, car and petrol costs that would need to be paid for out of a very limited and stagnant pool of money. No matter which way I spun them, the numbers never balanced out.

Kristian and I discussed what we could do to improve our financial situation. He offered to take the kids for another night during the week so I could take on extra work. We negotiated until we reached a mid-point agreement that neither of us was entirely happy with. In hindsight, this was probably a good indication that it was pretty fair.

Try to work out what you absolutely need legal advice on and what you can sort out between yourselves. If you get 80% of an agreement in place together, it will be a lot less stressful and expensive to get the remaining 20% finalised with legal assistance.

4 Play the long game

The early months of separation are often when things go awry. With so much fear and uncertainty, it’s like a game of Hungry Hippos, with each of you blindly grabbing as much as you can, as quickly as you can, afraid to lose out on anything, whether you want it or not.

When people ask me for advice, I tell them what I was told by others: “Play the long game.” Don’t look for the small wins that will make this day, or this week, or even this year easier. Look at the long-term goal. What’s important to you?

For us, it was our relationship and our children’s happiness. We placed a good relationship between ourselves above long-term financial security. For me, fighting for extra child maintenance each month at the expense of Kristian’s living arrangements didn’t seem like a solid long-term plan. I might have gained an extra bedroom, but for a lifetime of animosity it was never going to be worth it. In turn, Kristian placed being close to the children above his desire to run home to friends and family.

Choose your battles. Don’t fight for what you can get or what you have been told to expect – work out what you really want and how it will affect the relationship with your ex-partner for the next 20 years.

5 Write, don’t speak

Things didn’t always run smoothly, of course. There were arguments and fallouts, and some moments when I thought the wheels had entirely fallen off. In the most difficult times we often communicated best by email. It allowed us to consider what we wanted to say and then let the other person digest the words in their own time. During one particularly fraught discussion about money, Kristian sent me an email that was so beautifully written and so perfectly timed that I could say it saved our entire breakup.

Here’s a part of it: “I would like to believe we have the trust, integrity and maturity to deal with this in the right manner. I know you. I know you are not manipulative, nor selfish, nor deceitful. Our kids are a beautiful testament to both of us being honest, loving, loyal and all round beautiful people! I want us to remain great friends, not because of our kids, but because of all the great experiences we have encountered together and the growth through them.”

That email contained all the lessons any couple need for a good divorce: honesty, explanation, compassion and compromise.

Thursday 14 March 2019

Meritocracy is a myth invented by the rich

The college admissions scandal is a reminder that wealth, not talent, is what determines the opportunities you have in life writes Nathan Robinson in The Guardian

‘There can be never be such thing as a meritocracy, because there’s never going to be fully equal opportunity.’ Photograph: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images

The US college admissions scandal is fascinating, if not surprising. Over 30 wealthy parents have been criminally charged over a scheme in which they allegedly paid a company large sums of money to get their children into top universities. The duplicity involved was extreme: everything from paying off university officials to inventing learning disabilities to facilitate cheating on standardized tests. One father even faked a photo of his son pole vaulting in order to convince admissions officers that the boy was a star athlete.

It’s no secret that wealthy people will do nearly anything to get their kids into good schools. But this scandal only begins to reveal the lies that sustain the American idea of meritocracy. William “Rick” Singer, who admitted to orchestrating the scam, explained that there are three ways in which a student can get into the college of their choice: “There is a front door which is you get in on your own. The back door is through institutional advancement, which is ten times as much money. And I’ve created this side door.” The “side door” he’s referring to is outright crime, literally paying bribes and faking test scores. It’s impossible to know how common that is, but there’s reason to suspect it’s comparatively rare. Why? Because for the most part, the wealthy don’t need to pay illegal bribes. They can already pay perfectly legal ones.

In his 2006 book, The Price of Admission: How America’s Ruling Class Buys Its Way into Elite Colleges, Daniel Golden exposes the way that the top schools favor donors and the children of alumni. A Duke admissions officer recalls being given being given a box of applications she had intended to reject, but which were returned to her for “special” reconsideration. In cases where parents are expected to give very large donations upon a student’s admission, the applicant may be described as an “institutional development” candidate—letting them in would help develop the institution. Everyone by now is familiar with the way the Kushner family bought little Jared a place at Harvard. It only took $2.5m to convince the school that Jared was Harvard material.

The inequality goes so much deeper than that, though. It’s not just donations that put the wealthy ahead. Children of the top 1% (and the top 5%, and the top 20%) have spent their entire lives accumulating advantages over their counterparts at the bottom. Even in first grade the differences can be stark: compare the learning environment at one of Detroit’s crumbling public elementary schools to that at a private elementary school that costs tens of thousands of dollars a year. There are high schools, such as Phillips Academyin Andover, Massachusetts, that have billion dollar endowments. Around the country, the level of education you receive depend on how much money your parents have.

Even if we equalized public school funding, and abolished private schools, some children would be far more equal than others. 2.5m children in the United States go through homelessness every year in this country. The chaotic living situation that comes with poverty makes it much, much harder to succeed. This means that even those who go through Singer’s “front door” have not “gotten in on their own.” They’ve gotten in partly because they’ve had the good fortune to have a home life conducive to their success.

People often speak about “equality of opportunity” as the American aspiration. But having anything close to equal opportunity would require a radical re-engineering of society from top to bottom. As long as there are large wealth inequalities, there will be colossal differences in the opportunities that children have. No matter what admissions criteria are set, wealthy children will have the advantage. If admissions officers focus on test scores, parents will pay for extra tutoring and test prep courses. If officers focus instead on “holistic” qualities, pare. It’s simple: wealth always confers greater capacity to give your children the edge over other people’s children. If we wanted anything resembling a “meritocracy,” we’d probably have to start by instituting full egalitarian communism.

In reality, there can be never be such thing as a meritocracy, because there’s never going to be fully equal opportunity. The main function of the concept is to assure elites that they deserve their position in life. It eases the “anxiety of affluence,” that nagging feeling that they might be the beneficiaries of the arbitrary “birth lottery” rather than the products of their own individual ingenuity and hard work.

There’s something perverse about the whole competitive college system. But we can imagine a different world. If everyone was guaranteed free, high-quality public university education, and a public school education matched the quality of a private school education, there wouldn’t be anything to compete for.

Instead of the farce of the admissions process, by which students have to jump through a series of needless hoops in order to prove themselves worthy of being given a good education, just admit everyone who meets a clearly-established threshold for what it takes to do the coursework. It’s not as if the current system is selecting for intelligence or merit. The school you went to mostly tells us what economic class your parents were in. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

‘There can be never be such thing as a meritocracy, because there’s never going to be fully equal opportunity.’ Photograph: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images

The US college admissions scandal is fascinating, if not surprising. Over 30 wealthy parents have been criminally charged over a scheme in which they allegedly paid a company large sums of money to get their children into top universities. The duplicity involved was extreme: everything from paying off university officials to inventing learning disabilities to facilitate cheating on standardized tests. One father even faked a photo of his son pole vaulting in order to convince admissions officers that the boy was a star athlete.

It’s no secret that wealthy people will do nearly anything to get their kids into good schools. But this scandal only begins to reveal the lies that sustain the American idea of meritocracy. William “Rick” Singer, who admitted to orchestrating the scam, explained that there are three ways in which a student can get into the college of their choice: “There is a front door which is you get in on your own. The back door is through institutional advancement, which is ten times as much money. And I’ve created this side door.” The “side door” he’s referring to is outright crime, literally paying bribes and faking test scores. It’s impossible to know how common that is, but there’s reason to suspect it’s comparatively rare. Why? Because for the most part, the wealthy don’t need to pay illegal bribes. They can already pay perfectly legal ones.

In his 2006 book, The Price of Admission: How America’s Ruling Class Buys Its Way into Elite Colleges, Daniel Golden exposes the way that the top schools favor donors and the children of alumni. A Duke admissions officer recalls being given being given a box of applications she had intended to reject, but which were returned to her for “special” reconsideration. In cases where parents are expected to give very large donations upon a student’s admission, the applicant may be described as an “institutional development” candidate—letting them in would help develop the institution. Everyone by now is familiar with the way the Kushner family bought little Jared a place at Harvard. It only took $2.5m to convince the school that Jared was Harvard material.

The inequality goes so much deeper than that, though. It’s not just donations that put the wealthy ahead. Children of the top 1% (and the top 5%, and the top 20%) have spent their entire lives accumulating advantages over their counterparts at the bottom. Even in first grade the differences can be stark: compare the learning environment at one of Detroit’s crumbling public elementary schools to that at a private elementary school that costs tens of thousands of dollars a year. There are high schools, such as Phillips Academyin Andover, Massachusetts, that have billion dollar endowments. Around the country, the level of education you receive depend on how much money your parents have.

Even if we equalized public school funding, and abolished private schools, some children would be far more equal than others. 2.5m children in the United States go through homelessness every year in this country. The chaotic living situation that comes with poverty makes it much, much harder to succeed. This means that even those who go through Singer’s “front door” have not “gotten in on their own.” They’ve gotten in partly because they’ve had the good fortune to have a home life conducive to their success.

People often speak about “equality of opportunity” as the American aspiration. But having anything close to equal opportunity would require a radical re-engineering of society from top to bottom. As long as there are large wealth inequalities, there will be colossal differences in the opportunities that children have. No matter what admissions criteria are set, wealthy children will have the advantage. If admissions officers focus on test scores, parents will pay for extra tutoring and test prep courses. If officers focus instead on “holistic” qualities, pare. It’s simple: wealth always confers greater capacity to give your children the edge over other people’s children. If we wanted anything resembling a “meritocracy,” we’d probably have to start by instituting full egalitarian communism.

In reality, there can be never be such thing as a meritocracy, because there’s never going to be fully equal opportunity. The main function of the concept is to assure elites that they deserve their position in life. It eases the “anxiety of affluence,” that nagging feeling that they might be the beneficiaries of the arbitrary “birth lottery” rather than the products of their own individual ingenuity and hard work.

There’s something perverse about the whole competitive college system. But we can imagine a different world. If everyone was guaranteed free, high-quality public university education, and a public school education matched the quality of a private school education, there wouldn’t be anything to compete for.

Instead of the farce of the admissions process, by which students have to jump through a series of needless hoops in order to prove themselves worthy of being given a good education, just admit everyone who meets a clearly-established threshold for what it takes to do the coursework. It’s not as if the current system is selecting for intelligence or merit. The school you went to mostly tells us what economic class your parents were in. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

‘We spoke English to set ourselves apart’: how I rediscovered my mother tongue

While I was growing up in Nigeria, my parents deliberately never spoke their native Igbo language to us. But later it became an essential part of me. By Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani in The Guardian

When I was a child, my great-grandmother, whom we called Daa, came to live with my family in Umuahia in south-eastern Nigeria. My father had spent most of his infancy in her care, mostly during a period when his mother was preoccupied with her role as one of the founders of a local Assemblies of God church. As Daa grew older and weaker, he felt it was his turn to take care of her. After much persuasion, he finally convinced her to leave her humble dwellings in a village far from where we lived and come spend her last days in the comfort of our modern home.

Each time I watched her shuffle one foot in front of the other, her back bent almost double until her head nearly touched the top of her walking stick, it was hard to imagine my father’s descriptions of a Daa who was once one of the tallest and most stunning women around. The story went that the colonial-era arbitrator who presided over the dissolution of her first marriage found her so beautiful that he decided on the spot to take her as one of his wives. “How can you maltreat such a beautiful woman?” he was said to have asked the errant husband.

Daa’s favourite pastime turned out to be watching American wrestling matches on TV. She had lived almost an entire lifetime with no television; and yet no other entertainment that the channels had to offer caught her fancy. With her ashen legs stretched stiff in suspense, she stared agape, chuckled loudly and gasped audibly as Mighty Igor and his ilk beat each other up on the small screen. Daa also enjoyed telling stories. But, apart from popular words like “TV” and “rice”, she knew no English. Her one and only language was Igbo. This meant that her storytelling sessions often involvedvivid gesticulations and multiple repetitions so that my siblings and I could understand what she was trying to say, or so we could say anything that she understood.

None of us children spoke Igbo, our local language. Unlike the majority of their contemporaries in our hometown, my parents had chosen to speak only English to their children. Guests in our home adjusted to the fact that we were an English-speaking household, with varying degrees of success. Our helps were also encouraged to speak English. Many arrived from their remote villages unable to utter a single word of the foreign tongue, but as the weeks rolled by, they soon began to string complete sentences together with less contortion of their faces. My parents also spoke to each other in English – never mind that they had grown up speaking Igbo with their families. On the rare occasion my father and mother spoke Igbo to each other, it was a clear sign that they were conducting a conversation in which the children were not supposed to participate.

Over the years, I endured people teasing my parents – usually behind their backs – for this decision, accusing them of desiring to turn their children into white people. I read how the notorious former Ugandan president Idi Amin, in the 70s, brazenly addressed the United Nations in his mother tongue. The Congolese despot Mobutu Sese Seko also showed allegiance to his local language by dumping his European names. More recently, the internationally acclaimed Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, after a successful career writing in English, decided to switch almost entirely to writing in his native Gikuyu. Upholding one’s mother tongue over English appeared to be the ultimate demonstration of one’s love of people and country – a middle finger raised in the face of British colonialism.

Lee Kuan Yew, the first prime minister of Singapore, thought differently. When he replaced Chinese with English as the official medium of instruction in his country’s schools, activists accused him of trying to suppress culture. The media portrayed him as “the oppressor in a government of ‘pseudo foreigners who forget their ancestors’,” as he explained in his autobiography, From Third World to First. But he believed the future of his country’s children depended on their command of the language of the latest textbooks, which would undoubtedly be English.

“With English, no race would have an advantage,” he wrote. “English as our working language has … given us a competitive advantage because it is the international language of business and diplomacy, of science and technology. Without it, we would not have many of the world’s multinationals and over 200 of the world’s top banks in Singapore. Nor would our people have taken so readily to computers and the internet.” Within a few decades of independence from Britain in 1965, Singapore had risen from poverty and disorder to become an economic powerhouse. The country’s transformation under Yew’s guidance is often described as dramatic.

My parents shared Yew’s convictions. They hoped English would give their children an advantage. But, as potent as that reason might be, my father admitted to me that it was secondary. He had an even stronger motivation for preferring English: “We spoke it to set ourselves apart,” he said. “Those of us who were educated wanted to distinguish ourselves from those who had money but didn’t go to school.”

When I was a child, my great-grandmother, whom we called Daa, came to live with my family in Umuahia in south-eastern Nigeria. My father had spent most of his infancy in her care, mostly during a period when his mother was preoccupied with her role as one of the founders of a local Assemblies of God church. As Daa grew older and weaker, he felt it was his turn to take care of her. After much persuasion, he finally convinced her to leave her humble dwellings in a village far from where we lived and come spend her last days in the comfort of our modern home.

Each time I watched her shuffle one foot in front of the other, her back bent almost double until her head nearly touched the top of her walking stick, it was hard to imagine my father’s descriptions of a Daa who was once one of the tallest and most stunning women around. The story went that the colonial-era arbitrator who presided over the dissolution of her first marriage found her so beautiful that he decided on the spot to take her as one of his wives. “How can you maltreat such a beautiful woman?” he was said to have asked the errant husband.

Daa’s favourite pastime turned out to be watching American wrestling matches on TV. She had lived almost an entire lifetime with no television; and yet no other entertainment that the channels had to offer caught her fancy. With her ashen legs stretched stiff in suspense, she stared agape, chuckled loudly and gasped audibly as Mighty Igor and his ilk beat each other up on the small screen. Daa also enjoyed telling stories. But, apart from popular words like “TV” and “rice”, she knew no English. Her one and only language was Igbo. This meant that her storytelling sessions often involvedvivid gesticulations and multiple repetitions so that my siblings and I could understand what she was trying to say, or so we could say anything that she understood.

None of us children spoke Igbo, our local language. Unlike the majority of their contemporaries in our hometown, my parents had chosen to speak only English to their children. Guests in our home adjusted to the fact that we were an English-speaking household, with varying degrees of success. Our helps were also encouraged to speak English. Many arrived from their remote villages unable to utter a single word of the foreign tongue, but as the weeks rolled by, they soon began to string complete sentences together with less contortion of their faces. My parents also spoke to each other in English – never mind that they had grown up speaking Igbo with their families. On the rare occasion my father and mother spoke Igbo to each other, it was a clear sign that they were conducting a conversation in which the children were not supposed to participate.

Over the years, I endured people teasing my parents – usually behind their backs – for this decision, accusing them of desiring to turn their children into white people. I read how the notorious former Ugandan president Idi Amin, in the 70s, brazenly addressed the United Nations in his mother tongue. The Congolese despot Mobutu Sese Seko also showed allegiance to his local language by dumping his European names. More recently, the internationally acclaimed Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, after a successful career writing in English, decided to switch almost entirely to writing in his native Gikuyu. Upholding one’s mother tongue over English appeared to be the ultimate demonstration of one’s love of people and country – a middle finger raised in the face of British colonialism.

Lee Kuan Yew, the first prime minister of Singapore, thought differently. When he replaced Chinese with English as the official medium of instruction in his country’s schools, activists accused him of trying to suppress culture. The media portrayed him as “the oppressor in a government of ‘pseudo foreigners who forget their ancestors’,” as he explained in his autobiography, From Third World to First. But he believed the future of his country’s children depended on their command of the language of the latest textbooks, which would undoubtedly be English.

“With English, no race would have an advantage,” he wrote. “English as our working language has … given us a competitive advantage because it is the international language of business and diplomacy, of science and technology. Without it, we would not have many of the world’s multinationals and over 200 of the world’s top banks in Singapore. Nor would our people have taken so readily to computers and the internet.” Within a few decades of independence from Britain in 1965, Singapore had risen from poverty and disorder to become an economic powerhouse. The country’s transformation under Yew’s guidance is often described as dramatic.

My parents shared Yew’s convictions. They hoped English would give their children an advantage. But, as potent as that reason might be, my father admitted to me that it was secondary. He had an even stronger motivation for preferring English: “We spoke it to set ourselves apart,” he said. “Those of us who were educated wanted to distinguish ourselves from those who had money but didn’t go to school.”

Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani with her father and brothers in Umuahia in the early 1980s. Photograph: Courtesy of Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani

A perennial issue among the Igbo of south-eastern Nigeria is the battle between the mind and the purse; between certificate and cash. All over Nigeria, the Igbo are recognised for their entrepreneurial spirit and business acumen. From pre-colonial times to today, a majority of the country’s successful traders and transporters have been Igbo. Many of them began as apprentices and worked their way up, never bothering with school. The Igbo are also known for ostentatiousness and flamboyance – those with great wealth usually find it difficult to be silent about it. While the moguls flaunted their cash, the educated members of my parents’ generation flaunted their degrees, many from British and American schools. They might not have had the excess cash to fling at the masses during public functions or to acquire fleets of cars, but they could speak fluent English – an asset that was not available for purchase in stores.

I still remember strangers staring and smiling at us in wonder whenever my family talked among ourselves in public. Speaking English was just one way of showing off, especially when one lived, like my parents, in what was then a small, little-known town. Some of my parents’ contemporaries distinguished themselves by appending their academic qualifications to their names. Apart from academics and medical doctors, it was common to hear people describe themselves as Architect Peter or Engineer Paul or Pharmacist Okoro.

My father’s first degree was in economics, while my mother’s was in sociology. They met during the civil war between the government of Nigeria and the secessionist Igbo state of Biafra, and they spoke to each other in English throughout their three years of courtship, long before any of their children were born. “That was one of the things that attracted your daddy to me,” my mother said. “The way I spoke English fluently.” Back then, villagers made fun of my father for his choice of wife. They sneered that his determination to marry a university graduate had blinded him to the choice of a woman who was so skinny that she could surely never carry children successfully in her womb. Even if female university graduates were scarce, couldn’t he marry an uneducated woman and then send her to school?

The simmering resentment between those with certificates and those with cash exploded to the surface in the 1990s, when the Nigerian economy plunged. Suddenly, it was not so difficult to find an educated wife willing to marry a man who could also take on the responsibility of her parents’ and siblings’ welfare. Whether or not he could speak English or read and write was immaterial. Around that same time, a significant number of uneducated but daring Igbo men found infamy and fortune by swindling westerners of millions through advance fee fraud, known locally as 419 scams. There were stories of learned men – professors and engineers and accountants – being openly scorned during community meetings. “Thank you for your speech, but how much money are you going to contribute?” they would be asked. “We are not here to eat English. Please, sit down and keep quiet.” There were also stories of 419 scammers sneering back at those who mocked their incorrect English and inability to pronounce the names of their luxury cars. “You knows the name, I owns the car,” they would say.

This longstanding battle between the mind and the wallet is probably why Igbo has suffered the most among Nigeria’s three main languages. The other two, Yoruba and Hausa, despite facing threats from English as well, seem not to be doing as badly. Yoruba is one of the languages on a list of suggestions for London police officers to learn, while the BBC World Service’s Hausa-language operation has a larger audience than any other. Meanwhile, Igbo is among the world’s endangered languages, and there is a rising cry, especially among Igbo intellectuals, for drastic action to preserve and promote our mother tongue.

Many of the children who admired people like my family grew up determined that their own children would also speak English. My parents spoke excellent English – my father certified as an accountant in Britain, while my mother acquired a PGCE in education and then taught in London primary schools. They quoted Shakespeare and used words like “effluvium” in everyday speech. Not many of the new generation of parents speaking English to their children have a command of the language themselves. Unfortunately, the public school system in Nigeria has continued to deteriorate, and few parents can afford the private education that could provide their children with good English lessons. There is now an alarming number of young Igbo people who are not fluent in their mother tongue or in English.

My difficulty in communicating with Daa was not the only disadvantage of not being able to speak Igbo as a child. Each time it was my turn to stand and read to my primary school class from our recommended Igbo textbook, the pupils burst into grand giggles at my use of the wrong tones on the wrong syllables. Again and again, the teachers made me repeat. Each time, the class’s laughter was louder. My off-key pronunciations tickled them no end.

But while the other pupils were busy giggling, I went on to get the highest scores in Igbo tests. Always. Because the tests were written, they did not require the ability to pronounce words accurately. The rest of the class were relaxed in their understanding of the language, and so treated it casually. I considered Igbo foreign to me, and approached the subject studiously. I read Igbo literature and watched Igbo programmes on TV. My favourite was a series of comedy sketches called Mmadu O Bu Ewu, which featured a live goat dressed in human clothing. After studying Igbo from primary school through to the conclusion of secondary school, I was confident enough in my knowledge to register the language as one of my university entrance exam subjects.

Everyone thought me insane. Taking a major local language exam as a prerequisite for university admission was not child’s play. I was treading where expert speakers themselves feared to tread. Only two students in my entire school had chosen to take Igbo in these exams. But my Igbo score turned out to be good enough, when combined with my scores in the other two subjects I chose, to land me a place to study psychology at Nigeria’s prestigious University of Ibadan.

Eager to show off my hard-earned skill, whenever I come across publishers of African publications – especially those who make a big deal about propagating “African culture” – I ask if I can write something for them in Igbo. They always say no. Despite all the “promoting our culture” fanfare, they understand that local language submissions could limit the reach of their publications.

A perennial issue among the Igbo of south-eastern Nigeria is the battle between the mind and the purse; between certificate and cash. All over Nigeria, the Igbo are recognised for their entrepreneurial spirit and business acumen. From pre-colonial times to today, a majority of the country’s successful traders and transporters have been Igbo. Many of them began as apprentices and worked their way up, never bothering with school. The Igbo are also known for ostentatiousness and flamboyance – those with great wealth usually find it difficult to be silent about it. While the moguls flaunted their cash, the educated members of my parents’ generation flaunted their degrees, many from British and American schools. They might not have had the excess cash to fling at the masses during public functions or to acquire fleets of cars, but they could speak fluent English – an asset that was not available for purchase in stores.

I still remember strangers staring and smiling at us in wonder whenever my family talked among ourselves in public. Speaking English was just one way of showing off, especially when one lived, like my parents, in what was then a small, little-known town. Some of my parents’ contemporaries distinguished themselves by appending their academic qualifications to their names. Apart from academics and medical doctors, it was common to hear people describe themselves as Architect Peter or Engineer Paul or Pharmacist Okoro.