PTI in Times of India

India is ranked ninth in crony-capitalism with crony sector wealth accounting for 3.4 per cent of the gross domestic product (GDP), according to a new study by The Economist.

In India, the non-crony sector wealth amounts to 8.3 per cent of the GDP, as per the latest crony-capitalism index.

In 2014 rankings too, India stood at the ninth place.

Using data from a list of the world's billionaires and their worth published by Forbes, each individual is labelled as crony or not based on the source of their wealth.

Germany is cleanest, where just a sliver of the country's billionaires derive their wealth from crony sectors.

Russia fares worst in the index, wealth from the country's crony sectors amounts to 18 per cent of its GDP, it said.

Russia tops the list followed by Malaysia, the Philippines and Singapore.

"Thanks to tumbling energy and commodity prices politically connected tycoons have been feeling the squeeze in recent years," the study said.

Among the 22 economies in the index, crony wealth has fallen by USD 116 billion since 2014.

"But as things stand, if commodity prices rebound, crony capitalists wealth is sure to rise again," it added.

The past 20 years have been a golden age for crony capitalists--tycoons active in industries where chumminess with government is part of the game.

Their combined fortunes have dropped 16 per cent since 2014, according to The Economist updated crony-capitalism index.

"One reason is the commodity crash. Another is a backlash from the middle class," it said.

Worldwide, the worth of billionaires in crony industries soared by 385 per cent between 2004 and 2014 to USD 2 trillion, it added.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Sunday, 8 May 2016

Saturday, 7 May 2016

Is it science or theology?

Pervez Hoodbhoy in The Dawn

When Pakistani students open a physics or biology textbook, it is sometimes unclear whether they are actually learning science or, instead, theology. The reason: every science textbook, published by a government-run textbook board in Pakistan, by law must contain in its first chapter how Allah made our world, as well as how Muslims and Pakistanis have created science.

I have no problem with either. But the first properly belongs to Islamic Studies, the second to Islamic or Pakistani history. Neither legitimately belongs to a textbook on a modern-day scientific subject. That’s because religion and science operate very differently and have widely different assumptions. Religion is based on belief and requires the existence of a hereafter, whereas science worries only about the here and now.

Demanding that science and faith be tied together has resulted in national bewilderment and mass intellectual enfeeblement. Millions of Pakistanis have studied science subjects in school and then gone on to study technical, science-based subjects in college and university. And yet most — including science teachers — would flunk if given even the simplest science quiz.

How did this come about? Let’s take a quick browse through a current 10th grade physics book. The introductory section has the customary holy verses. These are followed by a comical overview of the history of physics. Newton and Einstein — the two greatest names — are unmentioned. Instead there’s Ptolemy the Greek, Al-Kindi, Al-Beruni, Ibn-e-Haytham, A.Q. Khan, and — amusingly — the heretical Abdus Salam.

The end-of-chapter exercises test the mettle of students with such questions as: Mark true/false; A) The first revelation sent to the Holy Prophet (PBUH) was about the creation of Heaven? B) The pin-hole camera was invented by Ibn-e-Haytham? C) Al-Beruni declared that Sind was an underwater valley that gradually filled with sand? D) Islam teaches that only men must acquire knowledge?

Dear Reader: You may well gasp in disbelief, or just hold your head in despair. How could Pakistan’s collective intelligence and the quality of what we teach our children have sunk so low? To see more such questions, or to check my translation from Urdu into English, please visit the websitehttp://eacpe.org/ where relevant pages from the above text (as well as from those discussed below) have been scanned and posted.

Take another physics book — this one (English) is for sixth-grade students. It makes abundantly clear its discomfort with the modern understanding of our universe’s beginning. The theory of the Big Bang is attributed to “a priest, George Lamaitre [sic] of Belgium”. The authors cunningly mention his faith hoping to discredit his science. Continuing, they declare that “although the Big Bang Theory is widely accepted, it probably will never be proved”.

While Georges Lemaître was indeed a Catholic priest, he was so much more. A professor of physics, he worked out the expanding universe solution to Einstein’s equations. Lemaître insisted on separating science from religion; he had publicly chided Pope Pius XII when the pontiff grandly declared that Lemaître’s results provided a scientific validation to Catholicism.

Local biology books are even more schizophrenic and confusing than the physics ones. A 10th-grade book starts off its section on ‘Life and its Origins’ unctuously quoting one religious verse after another. None of these verses hint towards evolution, and many Muslims believe that evolution is counter-religious. Then, suddenly, a full page annotated chart hits you in the face. Stolen from some modern biology book written in some other part of the world, it depicts various living organisms evolving into apes and then into modern humans. Ouch!

Such incoherent babble confuses the nature of science — its history, purpose, method, and fundamental content. If the authors are confused, just imagine the impact on students who must learn this stuff. What weird ideas must inhabit their minds!

Compounding scientific ignorance is prejudice. Most students have been persuaded into believing that Muslims alone invented science. And that the heroes of Muslim science such as Ibn-e-Haytham, Al-Khwarizmi, Omar Khayyam, Ibn-e-Sina, etc owed their scientific discoveries to their strong religious beliefs. This is wrong.

Science is the cumulative effort of humankind with its earliest recorded origins in Babylon and Egypt about 6,000 years ago, thereafter moving to China and India, and then Greece. It was a millennium later that science reached the lands of Islam, where it flourished for 400 years before moving on to Europe. Omar Khayyam, a Muslim, was doubtless a brilliant mathematician. But so was Aryabhatta, a Hindu. What does their faith have to do with their science? Natural geniuses have existed everywhere and at all times.

Today’s massive infusion of religion into the teaching of science dates to the Ziaul Haq days. It was not just school textbooks that were hijacked. In the 1980s, as an applicant to a university teaching position in whichever department, the university’s selection committee would first check your faith.

In those days a favourite question at Quaid-e-Azam University (as probably elsewhere) was to have a candidate recite Dua-i-Qunoot, a rather difficult prayer. Another was to name each of the Holy Prophet’s wives, or be quizzed about the ideology of Pakistan. Deftly posed questions could expose the particularities of the candidate’s sect, personal degree of adherence, and whether he had been infected by liberal ideas.

Most applicants meekly submitted to the grilling. Of these many rose to become today’s chairmen, deans, and vice-chancellors. The bolder ones refused, saying that the questions asked were irrelevant. With strong degrees earned from good overseas universities, they did not have to submit to their bullying inquisitors. Decades later, they are part of a widely dispersed diaspora. Though lost to Pakistan, they have done very well for themselves.

Science has no need for Pakistan; in the rest of the world it roars ahead. But Pakistan needs science because it is the basis of a modern economy and it enables people to gain decent livelihoods. To get there, matters of faith will have to be cleanly separated from matters of science. This is how peoples around the world have managed to keep their beliefs intact and yet prosper. Pakistan can too, but only if it wants.

When Pakistani students open a physics or biology textbook, it is sometimes unclear whether they are actually learning science or, instead, theology. The reason: every science textbook, published by a government-run textbook board in Pakistan, by law must contain in its first chapter how Allah made our world, as well as how Muslims and Pakistanis have created science.

I have no problem with either. But the first properly belongs to Islamic Studies, the second to Islamic or Pakistani history. Neither legitimately belongs to a textbook on a modern-day scientific subject. That’s because religion and science operate very differently and have widely different assumptions. Religion is based on belief and requires the existence of a hereafter, whereas science worries only about the here and now.

Demanding that science and faith be tied together has resulted in national bewilderment and mass intellectual enfeeblement. Millions of Pakistanis have studied science subjects in school and then gone on to study technical, science-based subjects in college and university. And yet most — including science teachers — would flunk if given even the simplest science quiz.

How did this come about? Let’s take a quick browse through a current 10th grade physics book. The introductory section has the customary holy verses. These are followed by a comical overview of the history of physics. Newton and Einstein — the two greatest names — are unmentioned. Instead there’s Ptolemy the Greek, Al-Kindi, Al-Beruni, Ibn-e-Haytham, A.Q. Khan, and — amusingly — the heretical Abdus Salam.

The end-of-chapter exercises test the mettle of students with such questions as: Mark true/false; A) The first revelation sent to the Holy Prophet (PBUH) was about the creation of Heaven? B) The pin-hole camera was invented by Ibn-e-Haytham? C) Al-Beruni declared that Sind was an underwater valley that gradually filled with sand? D) Islam teaches that only men must acquire knowledge?

Dear Reader: You may well gasp in disbelief, or just hold your head in despair. How could Pakistan’s collective intelligence and the quality of what we teach our children have sunk so low? To see more such questions, or to check my translation from Urdu into English, please visit the websitehttp://eacpe.org/ where relevant pages from the above text (as well as from those discussed below) have been scanned and posted.

Take another physics book — this one (English) is for sixth-grade students. It makes abundantly clear its discomfort with the modern understanding of our universe’s beginning. The theory of the Big Bang is attributed to “a priest, George Lamaitre [sic] of Belgium”. The authors cunningly mention his faith hoping to discredit his science. Continuing, they declare that “although the Big Bang Theory is widely accepted, it probably will never be proved”.

While Georges Lemaître was indeed a Catholic priest, he was so much more. A professor of physics, he worked out the expanding universe solution to Einstein’s equations. Lemaître insisted on separating science from religion; he had publicly chided Pope Pius XII when the pontiff grandly declared that Lemaître’s results provided a scientific validation to Catholicism.

Local biology books are even more schizophrenic and confusing than the physics ones. A 10th-grade book starts off its section on ‘Life and its Origins’ unctuously quoting one religious verse after another. None of these verses hint towards evolution, and many Muslims believe that evolution is counter-religious. Then, suddenly, a full page annotated chart hits you in the face. Stolen from some modern biology book written in some other part of the world, it depicts various living organisms evolving into apes and then into modern humans. Ouch!

Such incoherent babble confuses the nature of science — its history, purpose, method, and fundamental content. If the authors are confused, just imagine the impact on students who must learn this stuff. What weird ideas must inhabit their minds!

Compounding scientific ignorance is prejudice. Most students have been persuaded into believing that Muslims alone invented science. And that the heroes of Muslim science such as Ibn-e-Haytham, Al-Khwarizmi, Omar Khayyam, Ibn-e-Sina, etc owed their scientific discoveries to their strong religious beliefs. This is wrong.

Science is the cumulative effort of humankind with its earliest recorded origins in Babylon and Egypt about 6,000 years ago, thereafter moving to China and India, and then Greece. It was a millennium later that science reached the lands of Islam, where it flourished for 400 years before moving on to Europe. Omar Khayyam, a Muslim, was doubtless a brilliant mathematician. But so was Aryabhatta, a Hindu. What does their faith have to do with their science? Natural geniuses have existed everywhere and at all times.

Today’s massive infusion of religion into the teaching of science dates to the Ziaul Haq days. It was not just school textbooks that were hijacked. In the 1980s, as an applicant to a university teaching position in whichever department, the university’s selection committee would first check your faith.

In those days a favourite question at Quaid-e-Azam University (as probably elsewhere) was to have a candidate recite Dua-i-Qunoot, a rather difficult prayer. Another was to name each of the Holy Prophet’s wives, or be quizzed about the ideology of Pakistan. Deftly posed questions could expose the particularities of the candidate’s sect, personal degree of adherence, and whether he had been infected by liberal ideas.

Most applicants meekly submitted to the grilling. Of these many rose to become today’s chairmen, deans, and vice-chancellors. The bolder ones refused, saying that the questions asked were irrelevant. With strong degrees earned from good overseas universities, they did not have to submit to their bullying inquisitors. Decades later, they are part of a widely dispersed diaspora. Though lost to Pakistan, they have done very well for themselves.

Science has no need for Pakistan; in the rest of the world it roars ahead. But Pakistan needs science because it is the basis of a modern economy and it enables people to gain decent livelihoods. To get there, matters of faith will have to be cleanly separated from matters of science. This is how peoples around the world have managed to keep their beliefs intact and yet prosper. Pakistan can too, but only if it wants.

Friday, 6 May 2016

The lies binding Hillsborough to the battle of Orgreave

Ken Capstick in The Guardian

Police covered up their attacks on striking miners. And they used the same tactics after the football tragedy.

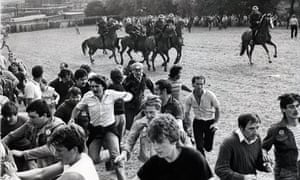

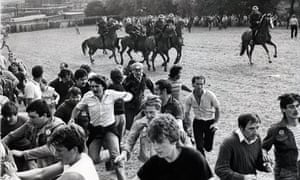

‘For those of us who were there when the ranks of police suddenly opened up and launched a cavalry charge, it felt like civil war.’ Photograph: Photofusion/Rex

Just eight miles separates the patch of ground on the outskirts of Sheffield where Orgreave coking plant once stood from Hillsborough stadium, where 96 people were unlawfully killed on 15 April 1989. To those of us involved in the miners’ strike in south Yorkshire in the 1980s, the so-called “battle of Orgreave” and Britain’s worst football disaster have always been linked.

It was a glorious summer’s day on 18 June 1984. With my son and other mineworkers, I set off for Orgreave to take part in a mass demonstration to try to stop coke being moved from the plant to the steelworks at Scunthorpe.

The miners were in a jovial mood, dressed in T-shirts and plimsolls. To save on petrol most of us travelled four or five to a car. We had been on strike for more than three months, had very little money and relied on the £2 picketing money from the union to pay for petrol. Our destination was to be the scene of one of the bloodiest battle grounds in Britain’s industrial history.

We went to Orgreave to fight to save our industry from what has since been revealed, following the release of cabinet papers in January 2014, as a government plan to kill off the coal mining industry, close 75 pits at a cost of approximately 75,000 jobs, and destroy the National Union of Mineworkers.

The battle of Orgreave was a one-sided contest, as miners suddenly found themselves facing not a police force, but a paramilitary force dressed in riot gear, wielding long truncheons, with strategically placed officers with dogs, and a cavalry charge reminiscent of a medieval battleground.

For those of us who were there when the ranks of police suddenly opened up and launched the charge on horseback, it felt like civil war. Miners had no defence other than to try and outrun the horses. Furthermore, we had to run uphill. Many miners were caught and battered to the ground with truncheons, then outnumbered by police on foot before being roughly handled as they were arrested. Those of us who made it to the top of the hill found refuge in a supermarket or in the nearby mining village.

‘Following the battle, 95 miners were charged with riot, an offence which can carry a life sentence.’ Photograph: Mike Forster/Associated News/Rex

No one died at Orgreave, but it was clearly the intention of the police to create what felt like a life-threatening situation. The police faced no threat from the miners at Orgreave that warranted such a violent response, but it was obvious to those present that the police knew they could act with impunity.

Following the battle, 95 miners were charged with riot, an offence which could carry a life sentence. Gareth Peirce, one of the defending solicitors in the abortive trial that followed, wrote in the Guardian in 1985: “Orgreave … revealed that in this country we now have a standing army available to be deployed against gatherings of civilians whose congregation is disliked by senior police officers. It is answerable to no one; it is trained in tactics which have been released to no one, but which include the deliberate maiming and injuring of innocent persons to disperse them, in complete violation of the law.”

Miners' strike: IPCC considers unredacted Orgreave report

I wasn’t in court when the prosecution of the Orgreave miners was thrown out because the evidence did not stack up. But the trial revealed the way police would collaborate and coordinate evidence in order to get convictions or cover up the truth. In this sense, Orgreave can be seen as a dry run for what happened after the Hillsborough disaster in 1989. Had the South Yorkshire force not been allowed to get away with what they did at Orgreave, perhaps Hillsborough would never have happened.

As the Hillsborough inquest verdicts have shown, we cannot have an unaccountable police force charged with upholding the rule of law but immune to it. We need to know which politicians or officials gave such immunity to the police, if it was given.

Only a full public inquiry into Orgreave will get at the truth, an inquiry to which all documents must be revealed in unredacted form. This inquiry would not just be in the interests of the miners injured on that day, and in the interests of their families. It would be in all our interests, because we all need to understand how a police force came to believe it was a law unto itself. If we don’t, we risk creating the conditions in which another Hillsborough or Orgreave could happen.

In 1985 the miners shouted from the rooftops, but we weren’t heard. Ignored by the media, many gave up. What happened at Orgreave was not a human tragedy on the same scale as Hillsborough. But now, thanks to the tremendous campaign by the Hillsborough families who lost loved ones, and who refused to give up their fight for justice, we have the chance to discover the truth about what happened at Orgreave too.

Police covered up their attacks on striking miners. And they used the same tactics after the football tragedy.

‘For those of us who were there when the ranks of police suddenly opened up and launched a cavalry charge, it felt like civil war.’ Photograph: Photofusion/Rex

Just eight miles separates the patch of ground on the outskirts of Sheffield where Orgreave coking plant once stood from Hillsborough stadium, where 96 people were unlawfully killed on 15 April 1989. To those of us involved in the miners’ strike in south Yorkshire in the 1980s, the so-called “battle of Orgreave” and Britain’s worst football disaster have always been linked.

It was a glorious summer’s day on 18 June 1984. With my son and other mineworkers, I set off for Orgreave to take part in a mass demonstration to try to stop coke being moved from the plant to the steelworks at Scunthorpe.

The miners were in a jovial mood, dressed in T-shirts and plimsolls. To save on petrol most of us travelled four or five to a car. We had been on strike for more than three months, had very little money and relied on the £2 picketing money from the union to pay for petrol. Our destination was to be the scene of one of the bloodiest battle grounds in Britain’s industrial history.

We went to Orgreave to fight to save our industry from what has since been revealed, following the release of cabinet papers in January 2014, as a government plan to kill off the coal mining industry, close 75 pits at a cost of approximately 75,000 jobs, and destroy the National Union of Mineworkers.

The battle of Orgreave was a one-sided contest, as miners suddenly found themselves facing not a police force, but a paramilitary force dressed in riot gear, wielding long truncheons, with strategically placed officers with dogs, and a cavalry charge reminiscent of a medieval battleground.

For those of us who were there when the ranks of police suddenly opened up and launched the charge on horseback, it felt like civil war. Miners had no defence other than to try and outrun the horses. Furthermore, we had to run uphill. Many miners were caught and battered to the ground with truncheons, then outnumbered by police on foot before being roughly handled as they were arrested. Those of us who made it to the top of the hill found refuge in a supermarket or in the nearby mining village.

‘Following the battle, 95 miners were charged with riot, an offence which can carry a life sentence.’ Photograph: Mike Forster/Associated News/Rex

No one died at Orgreave, but it was clearly the intention of the police to create what felt like a life-threatening situation. The police faced no threat from the miners at Orgreave that warranted such a violent response, but it was obvious to those present that the police knew they could act with impunity.

Following the battle, 95 miners were charged with riot, an offence which could carry a life sentence. Gareth Peirce, one of the defending solicitors in the abortive trial that followed, wrote in the Guardian in 1985: “Orgreave … revealed that in this country we now have a standing army available to be deployed against gatherings of civilians whose congregation is disliked by senior police officers. It is answerable to no one; it is trained in tactics which have been released to no one, but which include the deliberate maiming and injuring of innocent persons to disperse them, in complete violation of the law.”

Miners' strike: IPCC considers unredacted Orgreave report

I wasn’t in court when the prosecution of the Orgreave miners was thrown out because the evidence did not stack up. But the trial revealed the way police would collaborate and coordinate evidence in order to get convictions or cover up the truth. In this sense, Orgreave can be seen as a dry run for what happened after the Hillsborough disaster in 1989. Had the South Yorkshire force not been allowed to get away with what they did at Orgreave, perhaps Hillsborough would never have happened.

As the Hillsborough inquest verdicts have shown, we cannot have an unaccountable police force charged with upholding the rule of law but immune to it. We need to know which politicians or officials gave such immunity to the police, if it was given.

Only a full public inquiry into Orgreave will get at the truth, an inquiry to which all documents must be revealed in unredacted form. This inquiry would not just be in the interests of the miners injured on that day, and in the interests of their families. It would be in all our interests, because we all need to understand how a police force came to believe it was a law unto itself. If we don’t, we risk creating the conditions in which another Hillsborough or Orgreave could happen.

In 1985 the miners shouted from the rooftops, but we weren’t heard. Ignored by the media, many gave up. What happened at Orgreave was not a human tragedy on the same scale as Hillsborough. But now, thanks to the tremendous campaign by the Hillsborough families who lost loved ones, and who refused to give up their fight for justice, we have the chance to discover the truth about what happened at Orgreave too.

Thursday, 5 May 2016

Medical Council of India similar to BCCI?

The Hindu

The Supreme Court has given the Centre a deserved rebuke by using its extraordinary powers and setting up a three-member committee headed by former Chief Justice of India R.M. Lodha to perform the statutory functions of the Medical Council of India. The government now has a year to restructure the MCI, the regulatory body for medical education and professional practice. The Centre’s approach to reforming the corruption-afflicted MCI has been wholly untenable; the Dr. Ranjit Roy Chaudhury expert committee that it set up and the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare in the Rajya Sabha had both recommended structural change through amendments to the Indian Medical Council Act. Now that the Lodha panel will steer the MCI, there is hope that key questions swept under the carpet at the council will be addressed quickly. Among the most important is the need to reduce the cost of medical education and increase access in different parts of the country. This must be done to improve the doctor-to-population ratio, which is one for every 1,674 persons, as per the parliamentary panel report, against the WHO-recommended one to 1,000. In fact, it may be even less functionally because not all registered professionals practice medicine. In reality, only people in bigger cities and towns have reasonable access to doctors and hospitals. Removing bottlenecks to starting colleges, such as conditions stipulating the possession of a vast extent of land and needlessly extensive infrastructure, will considerably rectify the imbalance, especially in under-served States. The primary criterion to set up a college should only be the availability of suitable facilities to impart quality medical education.

The development of health facilities has long been affected by a sharp asymmetry between undergraduate and postgraduate seats in medicine. There are only about 25,000 PG seats, against a capacity of 55,000 graduate seats. The Lodha committee is in a position to review this gap, and it can help the Centre expand the system, especially through not-for-profit initiatives. There is also the contentious issue of choosing a common entrance examination. Although the Supreme Court has allowed the National Eligibility-cum-Entrance Test, some States are raising genuine concerns about equity and access. A reform agenda for the MCI must include an admission procedure that eliminates multiplicity of entrance examinations and addresses issues such as the urban-rural divide and language barriers. The Centre’s lack of preparedness in this matter, even after it was deliberated by the parliamentary panel, is all too glaring. The single most important issue that the Lodha committee would have to address is corruption in medical education, in which the MCI is mired. Appointing prominent persons from various fields to a restructured council would shine the light of transparency, and save it from reverting to its image as an “exclusive club” of socially disconnected doctors.

The Supreme Court has given the Centre a deserved rebuke by using its extraordinary powers and setting up a three-member committee headed by former Chief Justice of India R.M. Lodha to perform the statutory functions of the Medical Council of India. The government now has a year to restructure the MCI, the regulatory body for medical education and professional practice. The Centre’s approach to reforming the corruption-afflicted MCI has been wholly untenable; the Dr. Ranjit Roy Chaudhury expert committee that it set up and the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare in the Rajya Sabha had both recommended structural change through amendments to the Indian Medical Council Act. Now that the Lodha panel will steer the MCI, there is hope that key questions swept under the carpet at the council will be addressed quickly. Among the most important is the need to reduce the cost of medical education and increase access in different parts of the country. This must be done to improve the doctor-to-population ratio, which is one for every 1,674 persons, as per the parliamentary panel report, against the WHO-recommended one to 1,000. In fact, it may be even less functionally because not all registered professionals practice medicine. In reality, only people in bigger cities and towns have reasonable access to doctors and hospitals. Removing bottlenecks to starting colleges, such as conditions stipulating the possession of a vast extent of land and needlessly extensive infrastructure, will considerably rectify the imbalance, especially in under-served States. The primary criterion to set up a college should only be the availability of suitable facilities to impart quality medical education.

The development of health facilities has long been affected by a sharp asymmetry between undergraduate and postgraduate seats in medicine. There are only about 25,000 PG seats, against a capacity of 55,000 graduate seats. The Lodha committee is in a position to review this gap, and it can help the Centre expand the system, especially through not-for-profit initiatives. There is also the contentious issue of choosing a common entrance examination. Although the Supreme Court has allowed the National Eligibility-cum-Entrance Test, some States are raising genuine concerns about equity and access. A reform agenda for the MCI must include an admission procedure that eliminates multiplicity of entrance examinations and addresses issues such as the urban-rural divide and language barriers. The Centre’s lack of preparedness in this matter, even after it was deliberated by the parliamentary panel, is all too glaring. The single most important issue that the Lodha committee would have to address is corruption in medical education, in which the MCI is mired. Appointing prominent persons from various fields to a restructured council would shine the light of transparency, and save it from reverting to its image as an “exclusive club” of socially disconnected doctors.

If "Protest never changes anything"? Look at how TTIP has been derailed

Owen Jones in The Guardian

People power has taken on big business over this transatlantic stitch-up and looks like winning. We should all be inspired.

Doubts rise over TTIP as France threatens to block EU-US deal

Those of us who campaigned against TTIP – not least fellow Guardian columnist George Monbiot – were dismissed as scaremongering. We said that TTIP would lead to a race to the bottom on everything from environmental to consumer protections, forcing us down to the lower level that exists in the United States. We warned that it would undermine our democracy and sovereignty, enabling corporate interests to use secret courts to block policies that they did not like.

Scaremongering, we were told. But hundreds of leaked documents from the negotiations reveal, in some ways, that the reality is worse – and now the French government has been forced to suggest it may block the agreement.

The documents imply that even craven European leaders believe the US demands go too far. As War on Want puts it, they show that TTIP would “open the door” to products currently banned in the EU “for public health and environmental reasons”.

As the documents reveal, there are now “irreconcilable” differences between the European Union’s and America’s positions. According to Greenpeace, “the EU position is very bad, and the US position is terrible”.

The documents show that the US is actively trying to dilute EU regulations on consumer and environmental protections. In future, for the EU to be even able to pass a regulation, it could be forced to involve both US authorities and US corporations, giving big businesses across the Atlantic the same input as those based in Europe.

With these damning revelations, the embattled French authorities have been forced to say they reject TTIP “at this stage”. President Hollande says France would refuse “the undermining of the essential principles of our agriculture, our culture, of mutual access to public markets”. And with the country’s trade representative saying that “there cannot be an agreement without France and much less against France”, TTIP currently has a bleak future indeed.

There are a number of things we learn from this, all of which should lift hopes. First, people power pays off. European politicians and bureaucrats, quite rightly, would never have imagined that a trade agreement would inspire any interest, let alone mass protests. Symptomatic of their contempt for the people they supposedly exist to serve, the negotiations over the most important aspects of the treaty were conducted in secret. Easy, then, to accuse anti-TTIP activists of “scaremongering” while revealing little of the reality publicly.

But rather than give up, activists across the continent organised. They toxified TTIP, forcing its designers on the defensive. Germany – the very heart of the European project – witnessed mass demonstrations with up to 250,000 people participating.

From London to Warsaw, from Prague to Madrid, the anti-TTIP cause has marched. Members of the European parliament have been subjected to passionate lobbying by angry citizens. Without this popular pressure, TTIP would have received little scrutiny and would surely have passed – with disastrous consequences.

Second, this is a real embarrassment to the British government. Back in 2011, David Cameron vetoed an EU treaty to supposedly defend the national interest: in fact, he was worried that it threatened Britain’s financial sector. The City of London and Britain are clearly not the same thing. But Cameron has been among the staunchest champions of TTIP. He is more than happy to undermine British sovereignty and democracy, as long as it is corporate interests who are the beneficiaries.

And so we end in the perverse situation where it is the French government, rather than our own administration, protecting our sovereignty.

And third, this has real consequences for the EU referendum debate. Rather cynically, Ukip have co-opted the TTIP argument. They have rightly argued that TTIP threatens our National Health Service – but given that their leader, Nigel Farage, has suggested abolishing the NHS in favour of private health insurance, this is the height of chutzpah.

Ukip have mocked those on the left, such as me, who back a critical remain position in the Brexit referendum over this issue. But if we were to leave the EU, not only would the social chapter and various workers’ rights be abandoned – and not replaced by our rightwing government – but Britain would end up negotiating a series of TTIP agreements. We would end up living with the consequences of TTIP, but without the remaining progressive elements of the EU.

Instead, we have seen what happens when ordinary Europeans put aside cultural and language barriers and unite. Their collective strength can achieve results. This should surely be a launchpad for a movement to build a democratic, accountable, transparent Europe governed in the interests of its citizens, not corporations. It will mean reaching across the Atlantic too.

For all President Obama’s hope-change rhetoric, his administration – which zealously promoted TTIP – has all too often championed corporate interests. However, though Bernie Sanders is unlikely to become the Democratic nominee, the incredible movement behind him shows – particularly among younger Americans – a growing desire for a different sort of US.

In the coming months, those Europeans who have campaigned against TTIP should surely reach out to their American counterparts. Even if TTIP is defeated, we still live in a world in which major corporations often have greater power than nation states: only organised movements that cross borders can have any hope of challenging this unaccountable dominance.

From tax justice to climate change, the “protest never achieves anything” brigade have been proved wrong. Here’s a potential victory to relish, and build on.

People power has taken on big business over this transatlantic stitch-up and looks like winning. We should all be inspired.

Illustration by Ben Jennings

For those of us who want societies run in the interests of the majority rather than unaccountable corporate interests, this era can be best defined as an uphill struggle. So when victories occur, they should be loudly trumpeted to encourage us in a wider fight against a powerful elite of big businesses, media organisations, politicians, bureaucrats and corporate-funded thinktanks.

Today is one such moment. The Transatlantic Trade Investment Partnership (TTIP) – that notorious proposed trade agreement that hands even more sweeping powers to corporate titans – lies wounded, perhaps fatally. It isn’t dead yet, but TTIP is a tangled wreckage that will be difficult to reassemble.

For those of us who want societies run in the interests of the majority rather than unaccountable corporate interests, this era can be best defined as an uphill struggle. So when victories occur, they should be loudly trumpeted to encourage us in a wider fight against a powerful elite of big businesses, media organisations, politicians, bureaucrats and corporate-funded thinktanks.

Today is one such moment. The Transatlantic Trade Investment Partnership (TTIP) – that notorious proposed trade agreement that hands even more sweeping powers to corporate titans – lies wounded, perhaps fatally. It isn’t dead yet, but TTIP is a tangled wreckage that will be difficult to reassemble.

Doubts rise over TTIP as France threatens to block EU-US deal

Those of us who campaigned against TTIP – not least fellow Guardian columnist George Monbiot – were dismissed as scaremongering. We said that TTIP would lead to a race to the bottom on everything from environmental to consumer protections, forcing us down to the lower level that exists in the United States. We warned that it would undermine our democracy and sovereignty, enabling corporate interests to use secret courts to block policies that they did not like.

Scaremongering, we were told. But hundreds of leaked documents from the negotiations reveal, in some ways, that the reality is worse – and now the French government has been forced to suggest it may block the agreement.

The documents imply that even craven European leaders believe the US demands go too far. As War on Want puts it, they show that TTIP would “open the door” to products currently banned in the EU “for public health and environmental reasons”.

As the documents reveal, there are now “irreconcilable” differences between the European Union’s and America’s positions. According to Greenpeace, “the EU position is very bad, and the US position is terrible”.

The documents show that the US is actively trying to dilute EU regulations on consumer and environmental protections. In future, for the EU to be even able to pass a regulation, it could be forced to involve both US authorities and US corporations, giving big businesses across the Atlantic the same input as those based in Europe.

With these damning revelations, the embattled French authorities have been forced to say they reject TTIP “at this stage”. President Hollande says France would refuse “the undermining of the essential principles of our agriculture, our culture, of mutual access to public markets”. And with the country’s trade representative saying that “there cannot be an agreement without France and much less against France”, TTIP currently has a bleak future indeed.

There are a number of things we learn from this, all of which should lift hopes. First, people power pays off. European politicians and bureaucrats, quite rightly, would never have imagined that a trade agreement would inspire any interest, let alone mass protests. Symptomatic of their contempt for the people they supposedly exist to serve, the negotiations over the most important aspects of the treaty were conducted in secret. Easy, then, to accuse anti-TTIP activists of “scaremongering” while revealing little of the reality publicly.

But rather than give up, activists across the continent organised. They toxified TTIP, forcing its designers on the defensive. Germany – the very heart of the European project – witnessed mass demonstrations with up to 250,000 people participating.

From London to Warsaw, from Prague to Madrid, the anti-TTIP cause has marched. Members of the European parliament have been subjected to passionate lobbying by angry citizens. Without this popular pressure, TTIP would have received little scrutiny and would surely have passed – with disastrous consequences.

Second, this is a real embarrassment to the British government. Back in 2011, David Cameron vetoed an EU treaty to supposedly defend the national interest: in fact, he was worried that it threatened Britain’s financial sector. The City of London and Britain are clearly not the same thing. But Cameron has been among the staunchest champions of TTIP. He is more than happy to undermine British sovereignty and democracy, as long as it is corporate interests who are the beneficiaries.

And so we end in the perverse situation where it is the French government, rather than our own administration, protecting our sovereignty.

And third, this has real consequences for the EU referendum debate. Rather cynically, Ukip have co-opted the TTIP argument. They have rightly argued that TTIP threatens our National Health Service – but given that their leader, Nigel Farage, has suggested abolishing the NHS in favour of private health insurance, this is the height of chutzpah.

Ukip have mocked those on the left, such as me, who back a critical remain position in the Brexit referendum over this issue. But if we were to leave the EU, not only would the social chapter and various workers’ rights be abandoned – and not replaced by our rightwing government – but Britain would end up negotiating a series of TTIP agreements. We would end up living with the consequences of TTIP, but without the remaining progressive elements of the EU.

Instead, we have seen what happens when ordinary Europeans put aside cultural and language barriers and unite. Their collective strength can achieve results. This should surely be a launchpad for a movement to build a democratic, accountable, transparent Europe governed in the interests of its citizens, not corporations. It will mean reaching across the Atlantic too.

For all President Obama’s hope-change rhetoric, his administration – which zealously promoted TTIP – has all too often championed corporate interests. However, though Bernie Sanders is unlikely to become the Democratic nominee, the incredible movement behind him shows – particularly among younger Americans – a growing desire for a different sort of US.

In the coming months, those Europeans who have campaigned against TTIP should surely reach out to their American counterparts. Even if TTIP is defeated, we still live in a world in which major corporations often have greater power than nation states: only organised movements that cross borders can have any hope of challenging this unaccountable dominance.

From tax justice to climate change, the “protest never achieves anything” brigade have been proved wrong. Here’s a potential victory to relish, and build on.

Only successful people can afford a CV of failure

Sonia Sodha in The Guardian

A Princeton professor’s frankness hides the grim reality about work for many young people

A Princeton professor’s frankness hides the grim reality about work for many young people

Students at Princeton University. Photograph: Mel Evans/AP

‘One of the most strangely inspirational things I’ve ever read.” “This is a beautiful thing.” These aren’t plaudits about the latest Booker shortlist, but some of the praise directed at a “CV of failure” published by Princeton professor Johannes Haushofer. I have to confess that when I heard about the failure CV, I too thought it was a lovely idea. But when I read it, while it’s clearly very well intentioned, it made me feel a little uncomfortable. Professor Haushofer explains at the top of his CV that most of what he tries fails, but people only see the success, which “sometimes gives others the impression that most things work out for me”. The failures he lists include not getting into postgraduate programmes at Cambridge or Stanford, not getting a Harvard professorship and failing to secure a Fulbright scholarship.

I’m sure this was aimed at a small group of his students, to demonstrate that even successful professors get papers rejected by academic journals, but I suspect that the overwhelmingly positive reaction the CV has received in academic circles and on social media tells us more about our idealised view of success than the reality.

Those who are most successful have an understandable interest in emphasising that they got there through old-fashioned grit, persevering in the face of failure, never letting setbacks beat them down. Quite frankly, it’s a far more attractive way to package success than sharing a story of how it just happened to fall in your lap or how your innate abilities are so brilliant that they effortlessly propelled you to the top. Our favourite success story goes: sure, I may have some natural advantages, but I’m essentially like you, I just worked really hard to get where I am.

This also has the advantage of fitting the narrative that we want young people to buy. Work hard, keep plugging away and success will be round the corner. If you don’t put the effort in you won’t get there. It’s supported by the theory of success documented by Malcolm Gladwell in his book Outliers: people with exceptional expertise have invariably invested at least 10,000 hours of practice.

Of course, this is an important life lesson. We don’t want young people thinking that success is a matter of luck, otherwise they might feel like packing up and going home rather than slogging their guts out at school. There’s no question that effort is often correlated with success. but there there’s a serious danger that in patting ourselves on the back in sharing lessons about failure, we miss out some hard truths about the world. It’s much easier to talk about failure from the vantage of success. Oh yes, I know I get to write columns for a newspaper, but did I tell you about failing my driving test three times?

Sure, that’s a little flippant but there are lots of times when failure doesn’t end in success, and those stories contain as many important truths about how the world works. Those stories are much harder to share: like most people, I’d find it much more painful and difficult to be open about failures in those areas of my life that I don’t consider a triumph than those that I do.

Taken to the extreme, the risk is that telling ourselves these nice stories of success in terms of trying, failing, learning and trying again makes us too complacent that that’s the way the world really works. Sometimes, it does. But not always. Recent research has discredited Gladwell’s 10,000-hour rule, suggesting that practice accounts for just 12% of skill mastery and success. Buying too much into this myth in the face of the evidence undermines our understanding of a depressing and universal truth: the world is stacked against some young people before they’re even born.

‘One of the most strangely inspirational things I’ve ever read.” “This is a beautiful thing.” These aren’t plaudits about the latest Booker shortlist, but some of the praise directed at a “CV of failure” published by Princeton professor Johannes Haushofer. I have to confess that when I heard about the failure CV, I too thought it was a lovely idea. But when I read it, while it’s clearly very well intentioned, it made me feel a little uncomfortable. Professor Haushofer explains at the top of his CV that most of what he tries fails, but people only see the success, which “sometimes gives others the impression that most things work out for me”. The failures he lists include not getting into postgraduate programmes at Cambridge or Stanford, not getting a Harvard professorship and failing to secure a Fulbright scholarship.

I’m sure this was aimed at a small group of his students, to demonstrate that even successful professors get papers rejected by academic journals, but I suspect that the overwhelmingly positive reaction the CV has received in academic circles and on social media tells us more about our idealised view of success than the reality.

Those who are most successful have an understandable interest in emphasising that they got there through old-fashioned grit, persevering in the face of failure, never letting setbacks beat them down. Quite frankly, it’s a far more attractive way to package success than sharing a story of how it just happened to fall in your lap or how your innate abilities are so brilliant that they effortlessly propelled you to the top. Our favourite success story goes: sure, I may have some natural advantages, but I’m essentially like you, I just worked really hard to get where I am.

This also has the advantage of fitting the narrative that we want young people to buy. Work hard, keep plugging away and success will be round the corner. If you don’t put the effort in you won’t get there. It’s supported by the theory of success documented by Malcolm Gladwell in his book Outliers: people with exceptional expertise have invariably invested at least 10,000 hours of practice.

Of course, this is an important life lesson. We don’t want young people thinking that success is a matter of luck, otherwise they might feel like packing up and going home rather than slogging their guts out at school. There’s no question that effort is often correlated with success. but there there’s a serious danger that in patting ourselves on the back in sharing lessons about failure, we miss out some hard truths about the world. It’s much easier to talk about failure from the vantage of success. Oh yes, I know I get to write columns for a newspaper, but did I tell you about failing my driving test three times?

Sure, that’s a little flippant but there are lots of times when failure doesn’t end in success, and those stories contain as many important truths about how the world works. Those stories are much harder to share: like most people, I’d find it much more painful and difficult to be open about failures in those areas of my life that I don’t consider a triumph than those that I do.

Taken to the extreme, the risk is that telling ourselves these nice stories of success in terms of trying, failing, learning and trying again makes us too complacent that that’s the way the world really works. Sometimes, it does. But not always. Recent research has discredited Gladwell’s 10,000-hour rule, suggesting that practice accounts for just 12% of skill mastery and success. Buying too much into this myth in the face of the evidence undermines our understanding of a depressing and universal truth: the world is stacked against some young people before they’re even born.

Professor Johannes Haushofer said he had been judged by his successes. Photograph: Princeton University

I think it would be more useful for successful people to write a “CV of good fortune” than a “CV of failure”. A sort of: I’ve had much luck in my life: being born into a middle-class family and having any natural ability nurtured by my parents and then by the education system. It’s not to say that I can’t take any credit for any successes I might have had, but I think my own good fortune CV would contain more hard truths about how the world works than my failure CV.

Of course, good fortune CVs would send the wrong message to young people, who we want to be brimming with determination and resilience even when the world is stacked against them. We’ll never be able to eliminate the role that good fortune plays, but the flipside of encouraging young people to try, fail and try again is that we need to do much more to lessen its influence and to increase the relationship between effort and success.

Today’s labour market is tough enough for young people. Recession has hit their pay packets the hardest and it is not uncommon to find graduates working in a bar on a zero hours contract. Even while businesses complain about young people lacking employability skills, there is evidence that they are underinvesting in young people’s skills. On-the-job training has fallen in recent years and too many businesses have diverted government training subsidies for apprenticeships towards training that they would have been delivering anyway.

It’s only going to get tougher for some groups of young people. Yes, there will be new and exciting jobs in highly skilled careers we haven’t even dreamed of. But some growth sectors will be of a distinctly less glamorous sort, such as caring for our growing older population. These are currently low-skill, low-paid jobs, done mostly by women, held in low esteem. Yet there is a dearth of thinking about how we can make these jobs more fulfilling, better paid and more respected. It’s almost as if we’re hoping that the jobs at new frontiers of artificial intelligence will create enough trickle-down excitement to soften the blow for the young people who won’t get to do them.

Learning from failure is important but so is being able to get a job in which you’re invested in, supported to learn from your failures, and encouraged to progress. Yet we are reluctant to talk about the fact that, for too many young people, those jobs simply don’t yet exist when they reach the end of their education. It’s hard to see what good a failure CV will do them.

I think it would be more useful for successful people to write a “CV of good fortune” than a “CV of failure”. A sort of: I’ve had much luck in my life: being born into a middle-class family and having any natural ability nurtured by my parents and then by the education system. It’s not to say that I can’t take any credit for any successes I might have had, but I think my own good fortune CV would contain more hard truths about how the world works than my failure CV.

Of course, good fortune CVs would send the wrong message to young people, who we want to be brimming with determination and resilience even when the world is stacked against them. We’ll never be able to eliminate the role that good fortune plays, but the flipside of encouraging young people to try, fail and try again is that we need to do much more to lessen its influence and to increase the relationship between effort and success.

Today’s labour market is tough enough for young people. Recession has hit their pay packets the hardest and it is not uncommon to find graduates working in a bar on a zero hours contract. Even while businesses complain about young people lacking employability skills, there is evidence that they are underinvesting in young people’s skills. On-the-job training has fallen in recent years and too many businesses have diverted government training subsidies for apprenticeships towards training that they would have been delivering anyway.

It’s only going to get tougher for some groups of young people. Yes, there will be new and exciting jobs in highly skilled careers we haven’t even dreamed of. But some growth sectors will be of a distinctly less glamorous sort, such as caring for our growing older population. These are currently low-skill, low-paid jobs, done mostly by women, held in low esteem. Yet there is a dearth of thinking about how we can make these jobs more fulfilling, better paid and more respected. It’s almost as if we’re hoping that the jobs at new frontiers of artificial intelligence will create enough trickle-down excitement to soften the blow for the young people who won’t get to do them.

Learning from failure is important but so is being able to get a job in which you’re invested in, supported to learn from your failures, and encouraged to progress. Yet we are reluctant to talk about the fact that, for too many young people, those jobs simply don’t yet exist when they reach the end of their education. It’s hard to see what good a failure CV will do them.

Wednesday, 4 May 2016

Racism is a system of oppression, not a series of bloopers

Gary Younge in The Guardian

Gerry Adams was wrong to use the N-word. But to fetishise one off-colour comment over a life’s work is grotesque.

Gerry Adams was wrong to use the N-word. But to fetishise one off-colour comment over a life’s work is grotesque.

Gerry Adams: ‘a life’s work of internationalism and antiracist solidarity.’ Photograph: Charles McQuillan/Getty

On the weekend in 2001 when Oldham went up in flames during a series o fracially charged disturbances, I was at a garden party at the Hay-on-Wye literary festival – when I, along with many others, heard Germaine Greer using the term “nigger in a woodpile”. I walked away, not particularly interested in her justification for using that offensive word. By the time the weekend was through I’d had several calls from newspaper diarists asking me to comment on the incident.

I refused. Irritated as I had been, I saw no need to dignify the moment with more importance than it was due. On the weekend when working-class youth in one of Britain’s poorest cities took to the streets in protest, the fact that I had found a comment at a cocktail party from a fellow columnist racially offensive defied any decent sense of priority or proportion.

Make no mistake, I was offended and had every right to be. Words have consequences, and micro-aggressions matter. Often they are emblematic of broader issues; often they have an exclusory effect. This is a word that I’m not comfortable being around, even when black people use it. (Its use by the comedian Larry Wilmore to refer to Barack Obama at this weekend’s White House correspondents’ dinner set tongues wagging.) But being offended is not a political position. Not every display of ignorance is necessarily a slight; not every slight is worth escalating into an incident; not every provocation need be indulged.

Striking that balance is tricky. But it is no less important for that. There is a level of moralising sanctimony that increasingly comes with such moments, a gleeful righteousness – now urged on by social media – that amplifies the outrage and intensifies the shaming.

It is now the turn of Gerry Adams, the Sinn Féin leader, to be in the crosshairs. While watching the film Django Unchained, which tells the story of a freed slave who sets out to rescue his wife from a vicious Mississippi plantation owner with the help of a German bounty hunter, he tweeted: “Watching Django Unchained – A Ballymurphy Nigger”. He shouldn’t have done that. He was wrong. But his attempt to explain it in the context of the nationalist community’s treatment in Northern Ireland makes sense.

It’s a similar formulation to that used by Roddy Doyle in The Commitments. “The Irish are the niggers of Europe,” Jimmy Rabbitte Jr tells his fledgling band. “An’ Dubliners are the niggers of Ireland. An’ the northside Dubliners are the niggers o’ Dublin.” But The Commitments is 144 pages long; a tweet is just 140 characters. Context is important, and a tweet (soon deleted) stands alone.

On the weekend in 2001 when Oldham went up in flames during a series o fracially charged disturbances, I was at a garden party at the Hay-on-Wye literary festival – when I, along with many others, heard Germaine Greer using the term “nigger in a woodpile”. I walked away, not particularly interested in her justification for using that offensive word. By the time the weekend was through I’d had several calls from newspaper diarists asking me to comment on the incident.

I refused. Irritated as I had been, I saw no need to dignify the moment with more importance than it was due. On the weekend when working-class youth in one of Britain’s poorest cities took to the streets in protest, the fact that I had found a comment at a cocktail party from a fellow columnist racially offensive defied any decent sense of priority or proportion.

Make no mistake, I was offended and had every right to be. Words have consequences, and micro-aggressions matter. Often they are emblematic of broader issues; often they have an exclusory effect. This is a word that I’m not comfortable being around, even when black people use it. (Its use by the comedian Larry Wilmore to refer to Barack Obama at this weekend’s White House correspondents’ dinner set tongues wagging.) But being offended is not a political position. Not every display of ignorance is necessarily a slight; not every slight is worth escalating into an incident; not every provocation need be indulged.

Striking that balance is tricky. But it is no less important for that. There is a level of moralising sanctimony that increasingly comes with such moments, a gleeful righteousness – now urged on by social media – that amplifies the outrage and intensifies the shaming.

It is now the turn of Gerry Adams, the Sinn Féin leader, to be in the crosshairs. While watching the film Django Unchained, which tells the story of a freed slave who sets out to rescue his wife from a vicious Mississippi plantation owner with the help of a German bounty hunter, he tweeted: “Watching Django Unchained – A Ballymurphy Nigger”. He shouldn’t have done that. He was wrong. But his attempt to explain it in the context of the nationalist community’s treatment in Northern Ireland makes sense.

It’s a similar formulation to that used by Roddy Doyle in The Commitments. “The Irish are the niggers of Europe,” Jimmy Rabbitte Jr tells his fledgling band. “An’ Dubliners are the niggers of Ireland. An’ the northside Dubliners are the niggers o’ Dublin.” But The Commitments is 144 pages long; a tweet is just 140 characters. Context is important, and a tweet (soon deleted) stands alone.

After an initial hamfisted non-apology – blaming people for “misunderstanding the context in which [the word] was used” – Adams quickly graduated to a less grudging response, stating: “I apologise for any offence caused.” That should be the end of it.

To judge Adams, who has a life’s work of internationalism and antiracist solidarity, by a single tweet borders on the grotesque. People should be assessed on the body of their work, not just on a single off-colour statement. That doesn’t mean the statement should be ignored. But to fetishise it above a person’s record does a disservice not just to the person but to the issue.

As someone who, as an adult, has been stupid enough to ask gay men about their girlfriends and Jews how they enjoyed Christmas, I believe everyone has the right to misspeak, be set right, apologise and then carry on about their business. If that whole process is conducted in a spirit of generosity, then who knows? We might even learn something.

But if it’s not, all we have is an almighty game of gotcha with considerable collateral damage. This is not a new problem. In 2004 the football pundit Ron Atkinson was heard, when he thought the mic was off, referring to the Chelsea player Marcel Desailly thus: “He’s what is known in some schools as a fucking lazy thick nigger.” It was a reprehensible thing to say. He apologised, offered his resignation to ITV, which was accepted, and left his column in this newspaper by mutual agreement.

That’s as it should be. It is also the case that when it mattered he was one of the few coaches in British football who nurtured black talent, bringing on the likes of Cyrille Regis and Laurie Cunningham – both going on to play for England – and Brendon Batson. That excuses nothing that he said; but it makes a difference to how one chooses to describe, deride or disparage him in the wake of his awful comments.

Last year it was the turn of the actor Benedict Cumberbatch, who referred to how much things would have to improve before “coloured actors” could get the work they deserved in Britain. In the process of pointing out racism he came out with a word not used to identify black people for almost 40 years.

Racism is a system of oppression. It should not be reduced to series of gaffes. It not only cheapens the charge but essentially redefines it. Racism becomes not the subjugation of a people that has its roots in history, economics and power, but a series of bloopers in which the unfortunate are caught out. A matter of politics becomes an issue of politeness. The institutional is relegated to an indiscretion.

With the help of diversity consultants and a cautious manner, the careful can carry on doing bad things so long as they don’t say the wrong thing. That won’t get rid of racism. It’ll just give us some of the best-mannered racists in the world.

To judge Adams, who has a life’s work of internationalism and antiracist solidarity, by a single tweet borders on the grotesque. People should be assessed on the body of their work, not just on a single off-colour statement. That doesn’t mean the statement should be ignored. But to fetishise it above a person’s record does a disservice not just to the person but to the issue.

As someone who, as an adult, has been stupid enough to ask gay men about their girlfriends and Jews how they enjoyed Christmas, I believe everyone has the right to misspeak, be set right, apologise and then carry on about their business. If that whole process is conducted in a spirit of generosity, then who knows? We might even learn something.

But if it’s not, all we have is an almighty game of gotcha with considerable collateral damage. This is not a new problem. In 2004 the football pundit Ron Atkinson was heard, when he thought the mic was off, referring to the Chelsea player Marcel Desailly thus: “He’s what is known in some schools as a fucking lazy thick nigger.” It was a reprehensible thing to say. He apologised, offered his resignation to ITV, which was accepted, and left his column in this newspaper by mutual agreement.

That’s as it should be. It is also the case that when it mattered he was one of the few coaches in British football who nurtured black talent, bringing on the likes of Cyrille Regis and Laurie Cunningham – both going on to play for England – and Brendon Batson. That excuses nothing that he said; but it makes a difference to how one chooses to describe, deride or disparage him in the wake of his awful comments.

Last year it was the turn of the actor Benedict Cumberbatch, who referred to how much things would have to improve before “coloured actors” could get the work they deserved in Britain. In the process of pointing out racism he came out with a word not used to identify black people for almost 40 years.

Racism is a system of oppression. It should not be reduced to series of gaffes. It not only cheapens the charge but essentially redefines it. Racism becomes not the subjugation of a people that has its roots in history, economics and power, but a series of bloopers in which the unfortunate are caught out. A matter of politics becomes an issue of politeness. The institutional is relegated to an indiscretion.

With the help of diversity consultants and a cautious manner, the careful can carry on doing bad things so long as they don’t say the wrong thing. That won’t get rid of racism. It’ll just give us some of the best-mannered racists in the world.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)