The Magna Carta forced King John to give away powers. But big business now exerts a chilling grip on the workforce

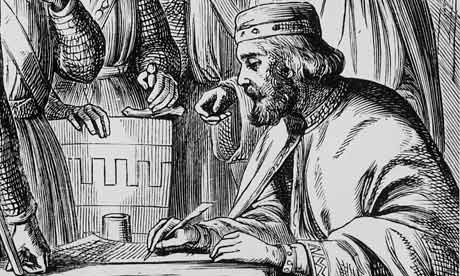

King John, surrounded by English barons, ratifying the Magna Carta at Runnymede. Photograph: Time Life Pictures/Getty Image

Hounded by police and bailiffs, evicted wherever they stopped, they did not mean to settle here. They had walked out of London to occupy disused farmland on the Queen's estates surrounding Windsor Castle. Perhaps unsurprisingly, that didn't work out very well. But after several days of pursuit, they landed two fields away from the place where modern democracy is commonly supposed to have been born.

At first this group of mostly young, dispossessed people, who (after the 17th century revolutionaries) call themselves Diggers 2012, camped on the old rugby pitch of Brunel University's Runnymede campus. It's a weed-choked complex of grand old buildings and modern halls of residence, whose mildewed curtains flap in the wind behind open windows, all mysteriously abandoned as if struck by a plague or a neutron bomb.

The diggers were evicted again, and moved down the hill into the woods behind the campus – pressed, as if by the ineluctable force of history, ever closer to the symbolic spot. From the meeting house they have built and their cluster of tents, you can see across the meadows to where the Magna Carta was sealed almost 800 years ago.

Their aim is simple: to remove themselves from the corporate economy, to house themselves, grow food and build a community on abandoned land. Implementation is less simple. Soon after I arrived, on a sodden day last week, an enforcer working for the company which now owns the land came slithering through the mud in his suit and patent leather shoes with a posse of police, to serve papers.

Already the crops the settlers had planted had been destroyed once; the day after my visit they were destroyed again. But the repeated destruction, removals and arrests have not deterred them. As one of their number, Gareth Newnham, told me: "If we go to prison we'll just come back … I'm not saying that this is the only way. But at least we're creating an opportunity for young people to step out of the system."

To be young in the post-industrial nations today is to be excluded. Excluded from the comforts enjoyed by preceding generations; excluded from jobs; excluded from hopes of a better world; excluded from self-ownership.

Those with degrees are owned by the banks before they leave college. Housing benefit is being choked off. Landlords now demand rents so high that only those with the better jobs can pay. Work has been sliced up and outsourced into a series of mindless repetitive tasks, whose practitioners are interchangeable. Through globalisation and standardisation, through unemployment and the erosion of collective bargaining and employment laws, big business now asserts a control over its workforce almost unprecedented in the age of universal suffrage.

The promise the old hold out to the young is a lifetime of rent, debt and insecurity. A rentier class holds the nation's children to ransom. Faced with these conditions, who can blame people for seeking an alternative?

But the alternatives have also been shut down: you are excluded yet you cannot opt out. The land – even disused land – is guarded as fiercely as the rest of the economy. Its ownership is scarcely less concentrated than it was when the Magna Carta was written. But today there is no Charter of the Forest (the document appended to the Magna Carta in 1217, granting the common people rights to use the royal estates). As Simon Moore, an articulate, well-read 27-year-old, explained, "those who control the land have enjoyed massive economic and political privileges. The relationship between land and democracy is a strong one, which is not widely understood."

As we sat in the wooden house the diggers have built, listening to the rain dripping from the eaves, the latest attempt to reform the House of Lords was collapsing in parliament. Almost 800 years after the Magna Carta was approved, unrepresentative power of the kind familiar to King John and his barons still holds sway. Even in the House of Commons, most seats are pocket boroughs, controlled by those who fund the major parties and establish the limits of political action.

Through such ancient powers, our illegitimate rulers sustain a system of ancient injustices, which curtail alternatives and lock the poor into rent and debt. This spring, the government dropped a clause into an unrelated bill so late that it could not be properly scrutinised by the House of Commons, criminalising the squatting of abandoned residential buildings.

The House of Lords, among whom the landowning class is still well-represented, approved the measure. Thousands of people who have solved their own housing crises will now be evicted, just as housing benefit payments are being cut back. I remember a political postcard from the early 1990s titled "Britain in 2020", which depicted the police rounding up some scruffy-looking people with the words, "you're under arrest for not owning or renting property". It was funny then; it's less funny today.

The young men and women camping at Runnymede are trying to revive a different tradition, largely forgotten in the new age of robber barons. They are seeking, in the words of the Diggers of 1649, to make "the Earth a common treasury for all … not one lording over another, but all looking upon each other as equals in the creation". The tradition of resistance, the assertion of independence from the laws devised to protect the landlords' ill-gotten property, long pre-date and long post-date the Magna Carta. But today they scarcely feature in national consciousness.

I set off in lashing rain to catch a train home from Egham, on the other side of the hill. As I walked into the town, I found the pavements packed with people. The rain bounced off their umbrellas, forming a silver mist. The front passed and the sun came out, and a few minutes later everyone began to cheer and wave their flags as the Olympic torch was carried down the road. The sense of common purpose was tangible, the readiness for sacrifice (in the form of a thorough soaking) just as evident. Half of what we need is here already. Now how do we recruit it to the fight for democracy?