Suresh Menon in The Hindu

One of the more amusing sights in cricket recently has been that of England trying desperately to work out a formula to simultaneously discipline Ben Stokes and retain him for the Ashes series. To be fair, such contortion is not unique. India once toured the West Indies with Navjot Singh Sidhu just after the player had been involved in a road rage case that led to a death.

Both times, the argument was one we hear politicians make all the time: Let the law takes its course. It is an abdication of responsibility by cricket boards fully aware of the obligation to uphold the image of the sport.

Cricketers, especially those who are talented, and therefore have been indulged, tend to enjoy what George Orwell has called the “benefit of the clergy”. Their star value is often a buffer against the kind of response others might have received. Given that the team leaves for Australia at the end of this month, it is unlikely that Stokes will tour anyway, yet the ECB’s reaction has been strange.

Neither Stokes nor Alex Hales, his partner at the brawl in Bristol which saw Stokes deliver what the police call ABH (Actual Bodily Harm), was dropped immediately from the squad. This is a pointer to the way cricket boards think.

An enquiry by the England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB) would not have taken more than a few hours. Given the cctv footage, the players’ own versions, and the testimony of the victims, it is unlikely that there could be any ambiguity about what happened. Yet the ECB has chosen to bring in its independent Cricket Discipline Commission only after the police have completed their inquiries.

Top sportsmen tend to be national heroes, unlike, say, top chartered accountants or geography teachers, and they have a responsibility to ensure they do not bring the sport into disrepute. It is a tough call, and not everybody agrees that your best all rounder should also be your most ideally-behaved human being. But that is the way it is. After all, sport is an artificial construct; rules around it might seem to be unrealistic too.

Stokes brought “the game into disrepute” — the reason Ian Botham and Andrew Flintoff were banned in the past — and he should not be in the team. The ECB’s response cannot be anything other than a ban. Yet, it is pussy-footing around the problem in the hope that there is a miracle. Perhaps the victims will not press charges. Perhaps the police might decide that the cctv images are inconclusive.

Clearly player behaviour is not the issue here. There are two other considerations. One was articulated by former Aussie captain Ian Chappell: Without Stokes, England stood no chance in the Ashes. The other, of equal if not greater concern to the ECB, is the impact of Stokes’s absence on sponsorship and advertising. Already the brewers Greene King has said it is withdrawing an advertisement featuring England players.

Scratch the surface on most moral issues, and you will hit the financial reasons that underlie them.

Stokes, it has been calculated, could lose up to two million pounds in endorsements, for “bringing the product into disrepute”, as written into the contracts. It will be interesting to see how the IPL deals with this — Stokes is the highest-paid foreign player in the tournament.

And yet — here is another sporting irony — there is the question of aggression itself. Stokes (like Botham and Flintoff and a host of others) accomplishes what he does on the field partly because of his fierce competitive nature and raw aggression.

Just as some players are intensely selfish, their selfishness being a reason for their success and therefore their team’s success, some players bring to the table sheer aggression.

Mike Atherton has suggested that Stokes should learn from Ricky Ponting who was constantly getting into trouble in bars early in his career. Ponting learnt to channelise that aggression and finished his career as one of the Aussie greats. A more recent example is David Warner, who paid for punching Joe Root in a bar some years ago, but seems to have settled down as both batsman and person.

Stokes will be missed at the Ashes. He has reduced England’s chances, even if Moeen Ali for one thinks that might not be the case.

Still, Stokes is only 26 and has many years to go. It is not too late to work on diverting all that aggression creatively. Doubtless he has been told this every time he has got into trouble. He is a rare talent, yet it would be a travesty if it all ended with a rap on the knuckles. England must live — however temporarily —without him.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Wednesday, 4 October 2017

Tuesday, 3 October 2017

The many shades of darkness and light

If we do not recognise the multiplicity of our past, we cannot accept the multiplicity of our present

Tabish Khair in The Hindu

For most Europeans and Europeanised peoples, Western modernity starts assuming shape with something called the Enlightenment, which, riding the steed of Pure Reason, sweeps away the preceding ‘Dark Ages’ of Europe. Similarly, for religious Muslims, the revelations of Islam mark a decisive break in Arabia from an earlier age of ignorance and superstition, often referred to as ‘Jahillia’.

Both the ideas are based on a perception of historical changes, but they also tinker with historical facts. In that sense, they are ideological: not ‘fake’, but a particular reading of the material realities that they set out to chronicle. Their light is real, but it blinds us to many things too.

For instance, it has been increasingly contested whether the European Dark Ages were as dark as the rhetoric of the Enlightenment assumes. It has also been doubted whether the Enlightenment shed as much light on the world as its champions claim. For instance, some of the darkest deeds to be perpetuated against non-Europeans were justified in the light of the notion of ‘historical progress’ demanded by the Enlightenment. Finally, even the movement away from religion to reason was not as clear-cut as it is assumed: well into the 19th century, Christianity (particularly Protestantism) was justified in terms of divinely illuminated reason as against the dark heathen superstitions of other faiths, and this logic has survived in subtler forms even today.

In a similar way, the Islamic notion of a prior age of Jahillia is partly a construct. While it might have applied to some Arab tribes most directly influenced by the coming of Islam, it was not as if pre-Islamic Arabia was simply a den of darkness and ignorance. There were developed forms of culture, poetry, worship and social organisation in so-called Jahillia too, all of which many religious Arab Muslims are not willing to consider as part of their own inheritance today. Once again, this notion of a past Jahillia has enabled extremists in Muslim societies to treat other people in brutal ways: a recent consequence was the 2001 destruction of the ancient Buddhas of Bamiyan statues by the Taliban in Afghanistan, not to mention the persecution of some supposed ‘idolators’ in Islamic State-occupied territories.

Achievements and an error

Both the notions — the Dark Ages followed by the Enlightenment and Jahillia followed by the illumination of Islam — are based on some real developments and achievements. Europe did move, slowly and often contradictorily, from religious and feudal authority to a greater tendency to reason and hence, finally, to allotting all individuals a theoretically equivalent (democratic) space as a human right rather than as a divine boon. Similarly, many parts of pre-Islamic Arabia (‘Jahillia’) did move from incessant social strife and a certain lack of cohesion to the far more organised, and hence hugely successful, politico-religious systems enabled by Islam. It might also be, as many religious Muslims claim, that early Islam marked some distinctively progressive and egalitarian values compared to the predominant tribalism of so-called Jahillia.

In both cases, however, the error has been to posit a complete break: a before-after scenario. This is not sustained by all the historical evidence. Why do I need to point this out? Because there are two great problems with positing such decisive before-after scenarios, apart from that of historical error.

Two problems of a complete break

First, it reduces one’s own complex relationship to one’s past to sheer negation. The past — as the Dark Ages or Jahillia — simply becomes a black hole into which we dump everything that we feel does not belong to our present. This reduces not only the past but also our present.

Second, the past — once reduced to a negative, obscure, dark caricature of our present — can then be used to persecute peoples who do not share our present. In that sense, the before-after scenario is aimed at the future. When Europeans set out to bring ‘Enlightenment’ values to non-European people, they also justified many atrocities by reasoning that these people were stuck in the dark ages of a past that should have vanished, and hence such people needed to be forcibly civilised for their own good. History could be recruited to explain away — no, even call for — the persecution that was necessary to ‘improve’ and ‘enlighten’ such people. I need not point out that some very religious Muslims thought in ways that were similar, and some fanatics still do.

I have often wondered whether the European Enlightenment did not adopt just Arab discoveries in philosophy or science, ranging from algebra to the theory of the camera. Perhaps their binary division of their own past is also an unconscious imitation of the Arab bifurcation of its past into dark ‘Jahillia’ and the light of Islam. Or maybe it is a sad ‘civilisational’ trend — for some caste Hindus tend to make a similar cut between ‘Arya’ and ‘pre-Arya’ pasts, with similar consequences: a dismissal of aboriginal cultures, practices and rights today as “lapsed” forms, or the whitewashing of Dravidian history by the fantasy of a permanent ‘Aryan’ presence in what is India.

All such attempts — Muslim, Arya-Hindu, or European — bear the germs of potential violence. After all, if we cannot accept our own evolving identities in the past, how can we accept our differences with others today? And if we cannot accept the diversity and richness of our multiple pasts, how can we accept the multiplicity of our present?

Tabish Khair in The Hindu

For most Europeans and Europeanised peoples, Western modernity starts assuming shape with something called the Enlightenment, which, riding the steed of Pure Reason, sweeps away the preceding ‘Dark Ages’ of Europe. Similarly, for religious Muslims, the revelations of Islam mark a decisive break in Arabia from an earlier age of ignorance and superstition, often referred to as ‘Jahillia’.

Both the ideas are based on a perception of historical changes, but they also tinker with historical facts. In that sense, they are ideological: not ‘fake’, but a particular reading of the material realities that they set out to chronicle. Their light is real, but it blinds us to many things too.

For instance, it has been increasingly contested whether the European Dark Ages were as dark as the rhetoric of the Enlightenment assumes. It has also been doubted whether the Enlightenment shed as much light on the world as its champions claim. For instance, some of the darkest deeds to be perpetuated against non-Europeans were justified in the light of the notion of ‘historical progress’ demanded by the Enlightenment. Finally, even the movement away from religion to reason was not as clear-cut as it is assumed: well into the 19th century, Christianity (particularly Protestantism) was justified in terms of divinely illuminated reason as against the dark heathen superstitions of other faiths, and this logic has survived in subtler forms even today.

In a similar way, the Islamic notion of a prior age of Jahillia is partly a construct. While it might have applied to some Arab tribes most directly influenced by the coming of Islam, it was not as if pre-Islamic Arabia was simply a den of darkness and ignorance. There were developed forms of culture, poetry, worship and social organisation in so-called Jahillia too, all of which many religious Arab Muslims are not willing to consider as part of their own inheritance today. Once again, this notion of a past Jahillia has enabled extremists in Muslim societies to treat other people in brutal ways: a recent consequence was the 2001 destruction of the ancient Buddhas of Bamiyan statues by the Taliban in Afghanistan, not to mention the persecution of some supposed ‘idolators’ in Islamic State-occupied territories.

Achievements and an error

Both the notions — the Dark Ages followed by the Enlightenment and Jahillia followed by the illumination of Islam — are based on some real developments and achievements. Europe did move, slowly and often contradictorily, from religious and feudal authority to a greater tendency to reason and hence, finally, to allotting all individuals a theoretically equivalent (democratic) space as a human right rather than as a divine boon. Similarly, many parts of pre-Islamic Arabia (‘Jahillia’) did move from incessant social strife and a certain lack of cohesion to the far more organised, and hence hugely successful, politico-religious systems enabled by Islam. It might also be, as many religious Muslims claim, that early Islam marked some distinctively progressive and egalitarian values compared to the predominant tribalism of so-called Jahillia.

In both cases, however, the error has been to posit a complete break: a before-after scenario. This is not sustained by all the historical evidence. Why do I need to point this out? Because there are two great problems with positing such decisive before-after scenarios, apart from that of historical error.

Two problems of a complete break

First, it reduces one’s own complex relationship to one’s past to sheer negation. The past — as the Dark Ages or Jahillia — simply becomes a black hole into which we dump everything that we feel does not belong to our present. This reduces not only the past but also our present.

Second, the past — once reduced to a negative, obscure, dark caricature of our present — can then be used to persecute peoples who do not share our present. In that sense, the before-after scenario is aimed at the future. When Europeans set out to bring ‘Enlightenment’ values to non-European people, they also justified many atrocities by reasoning that these people were stuck in the dark ages of a past that should have vanished, and hence such people needed to be forcibly civilised for their own good. History could be recruited to explain away — no, even call for — the persecution that was necessary to ‘improve’ and ‘enlighten’ such people. I need not point out that some very religious Muslims thought in ways that were similar, and some fanatics still do.

I have often wondered whether the European Enlightenment did not adopt just Arab discoveries in philosophy or science, ranging from algebra to the theory of the camera. Perhaps their binary division of their own past is also an unconscious imitation of the Arab bifurcation of its past into dark ‘Jahillia’ and the light of Islam. Or maybe it is a sad ‘civilisational’ trend — for some caste Hindus tend to make a similar cut between ‘Arya’ and ‘pre-Arya’ pasts, with similar consequences: a dismissal of aboriginal cultures, practices and rights today as “lapsed” forms, or the whitewashing of Dravidian history by the fantasy of a permanent ‘Aryan’ presence in what is India.

All such attempts — Muslim, Arya-Hindu, or European — bear the germs of potential violence. After all, if we cannot accept our own evolving identities in the past, how can we accept our differences with others today? And if we cannot accept the diversity and richness of our multiple pasts, how can we accept the multiplicity of our present?

Monday, 2 October 2017

Capitalist? Socialist? It’s time we dropped such meaningless labels from our political discourse

Ben Chu in The Independent

The American essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson once observed that a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds. Swap “foolish consistency” for “foolish label” and one has a good description of our contemporary political discourse.

Theresa May defends “free market capitalism”. Jeremy Corbynmakes the case for “21st century socialism”. So the headlines and the news reports yell at us. So the party leaders themselves inform us in their speeches.

But what do these labels actually mean? What economic policies do they signify? What sort of societies do they describe?

The concept of capitalism dates back to the Industrial Revolution, when wealthy entrepreneurs owned the new physical “capital” that was made possible by advances in technology. The boss of the new textile factory was also the owner. And that ownership conferred immense economic power and social authority, as factory bosses could determine the wages and conditions of the workers.

But who owns the physical capital, the “means of production”, of our modern economy? It’s no longer the people who run the large organisations in which a great many of us work. Millions of us will be invested in these giant companies through our pension funds. Does that make us all “capitalists”, like little 19th century mill owners? Hardly. Economic power has been divorced from corporate ownership. But that doesn’t mean it’s been broadly shared.

Another wrinkle is that today’s most dynamic companies – think Google, Amazon and Uber – actually have very little “capital” in the classic meaning of the word. The value of such firms derives not from tangible equipment or commodities, but from their intellectual property, from the expertise of their high-skilled employees and, increasingly, their networks and brands.

“Socialism” is a similarly problematic label, dating from the era of political struggles between newly-organised workers and the established economic elite. But the workers won many of those battles, establishing workplace protections, universal voting rights and state welfare systems. So what does socialism mean in a modern context? Soviet Union-style central planning and the abolition of private property? Venezuelan-style price controls? Cuban-style suppression of civil liberties?

Or does it simply mean the state ownership of certain natural monopoly utilities? This seems to be the justification for the use of the label in relation to Labour’s election manifesto. But, following that rationale, should we describe the Netherlands as socialist because its rail system is state-owned? Is France socialist because it has a national energy company? Is Germany socialist because it has rent controls?

In fact all these countries are social democracies – a variety of developed-world market-based economy. Britain has another variety. So does Japan. So do the Scandinavian nations. These are all mixed economies, where markets coexist with some degree of state ownership and intervention. Even America, with its state-funded scientific research programmes and New Deal-era social security system, is really a mixed economy.

The idea that Theresa May and the Conservatives are offering a set of policies that can be usefully summed up as “capitalism” and Labour are offering something entirely distinct called “socialism”, is fatuous. There are certainly differences between the two major parties in their view of the proper borders between market and state within our mixed economy (bigger differences than there have been for several decades) – but their positions plainly still lie on a recognisable continuum.

Theresa May herself says she wants a louder voice for workers in company board rooms, and stresses that markets must operate “with the right rules and regulations”. And Jeremy Corbyn, for all the attempts by the right-wing press to portray him as a bloodthirsty revolutionary, is not calling for the nationalisation of supermarkets and car manufacturers.

People are time-poor, and labels can be a useful shorthand when we all know roughly what is being referred to. But these particular labels – “capitalist”, “socialist” – don’t facilitate understanding: they short-circuit it. They don’t encourage us to think seriously about the challenges of making our complex and rapidly-evolving economies work in ways that will raise living standards and opportunities for human flourishing. They are essentially a spur to mindless tribalism: an invitation to take part in the political equivalent of an English Civil War battle recreation society.

The best advice is to banish the hobgoblins. Ignore the labels and focus on the merit – or otherwise – of the policies.

The American essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson once observed that a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds. Swap “foolish consistency” for “foolish label” and one has a good description of our contemporary political discourse.

Theresa May defends “free market capitalism”. Jeremy Corbynmakes the case for “21st century socialism”. So the headlines and the news reports yell at us. So the party leaders themselves inform us in their speeches.

But what do these labels actually mean? What economic policies do they signify? What sort of societies do they describe?

The concept of capitalism dates back to the Industrial Revolution, when wealthy entrepreneurs owned the new physical “capital” that was made possible by advances in technology. The boss of the new textile factory was also the owner. And that ownership conferred immense economic power and social authority, as factory bosses could determine the wages and conditions of the workers.

But who owns the physical capital, the “means of production”, of our modern economy? It’s no longer the people who run the large organisations in which a great many of us work. Millions of us will be invested in these giant companies through our pension funds. Does that make us all “capitalists”, like little 19th century mill owners? Hardly. Economic power has been divorced from corporate ownership. But that doesn’t mean it’s been broadly shared.

Another wrinkle is that today’s most dynamic companies – think Google, Amazon and Uber – actually have very little “capital” in the classic meaning of the word. The value of such firms derives not from tangible equipment or commodities, but from their intellectual property, from the expertise of their high-skilled employees and, increasingly, their networks and brands.

“Socialism” is a similarly problematic label, dating from the era of political struggles between newly-organised workers and the established economic elite. But the workers won many of those battles, establishing workplace protections, universal voting rights and state welfare systems. So what does socialism mean in a modern context? Soviet Union-style central planning and the abolition of private property? Venezuelan-style price controls? Cuban-style suppression of civil liberties?

Or does it simply mean the state ownership of certain natural monopoly utilities? This seems to be the justification for the use of the label in relation to Labour’s election manifesto. But, following that rationale, should we describe the Netherlands as socialist because its rail system is state-owned? Is France socialist because it has a national energy company? Is Germany socialist because it has rent controls?

In fact all these countries are social democracies – a variety of developed-world market-based economy. Britain has another variety. So does Japan. So do the Scandinavian nations. These are all mixed economies, where markets coexist with some degree of state ownership and intervention. Even America, with its state-funded scientific research programmes and New Deal-era social security system, is really a mixed economy.

The idea that Theresa May and the Conservatives are offering a set of policies that can be usefully summed up as “capitalism” and Labour are offering something entirely distinct called “socialism”, is fatuous. There are certainly differences between the two major parties in their view of the proper borders between market and state within our mixed economy (bigger differences than there have been for several decades) – but their positions plainly still lie on a recognisable continuum.

Theresa May herself says she wants a louder voice for workers in company board rooms, and stresses that markets must operate “with the right rules and regulations”. And Jeremy Corbyn, for all the attempts by the right-wing press to portray him as a bloodthirsty revolutionary, is not calling for the nationalisation of supermarkets and car manufacturers.

People are time-poor, and labels can be a useful shorthand when we all know roughly what is being referred to. But these particular labels – “capitalist”, “socialist” – don’t facilitate understanding: they short-circuit it. They don’t encourage us to think seriously about the challenges of making our complex and rapidly-evolving economies work in ways that will raise living standards and opportunities for human flourishing. They are essentially a spur to mindless tribalism: an invitation to take part in the political equivalent of an English Civil War battle recreation society.

The best advice is to banish the hobgoblins. Ignore the labels and focus on the merit – or otherwise – of the policies.

Sunday, 1 October 2017

The pendulum swings against privatisation

Evidence suggests that ending state ownership works in some markets but not others

Tim Harford in The Financial Times

Political fashions can change quickly, as a glance at almost any western democracy will tell you. The pendulum of the politically possible swings back and forth. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the debates over privatisation and nationalisation.

In the late 1940s, experts advocated nationalisation on a scale hard to imagine today. Arthur Lewis thought the government should run the phone system, insurance and the car industry. James Meade wanted to socialise iron, steel and chemicals; both men later won Nobel memorial prizes in economics.

They were in tune with the times: the British government ended up owning not only utilities and heavy industry but airlines, travel agents and even the removal company, Pickfords. The pendulum swung back in the 1980s and early 1990s, as Margaret Thatcher and John Major began an ever more ambitious series of privatisations, concluding with water, electricity and the railways. The world watched, and often followed suit.

Was it all worth it? The question arises because the pendulum is swinging back again: Jeremy Corbyn, the bookies’ favourite to be the next UK prime minister, wants to renationalise the railways, electricity, water and gas. (He has not yet mentioned Pickfords.) Furthermore, he cites these ambitions as a reason to withdraw from the European single market.

Privatisation’s proponents mention the galvanising effect of the profit motive, or the entrepreneurial spirit of private enterprise. Opponents talk of fat cats and selling off the family silver

That is odd, since there is nothing in single market rules to prevent state ownership of railways and utilities — the excuse seems to be yet another Eurosceptic myth, the leftwing reflection of rightwing tabloids moaning about banana regulation. Since the entire British political class has lost its mind over Brexit, it would be unfair to single out Mr Corbyn on those grounds.

Still, he has reopened a debate that long seemed settled, and piqued my interest. Did privatisation work? Proponents sometimes mention the galvanising effect of the profit motive, or the entrepreneurial spirit of private enterprise. Opponents talk of fat cats and selling off the family silver. Realists might prefer to look at the evidence, and the ambitious UK programme has delivered plenty of that over the years.

There is no reason for a government to own Pickfords, but the calculus of privatisation is more subtle when it comes to natural monopolies — markets that are broadly immune to competition. If I am not satisfied with what Pickford’s has to offer me when I move home, I am not short of options. But the same is not true of the Royal Mail: if I want to write to my MP then the big red pillar box at the end of the street is really the only game in town.

Competition does sometimes emerge in unlikely seeming circumstances. British Telecom seemed to have an iron grip on telephone services in the UK — as did AT&T in the US. The grip melted away in the face of regulation and, more importantly, technological change.

Railways seem like a natural monopoly, yet there are two separate railway lines from my home town of Oxford into London, and two separate railway companies will sell me tickets for the journey. They compete with two bus companies; competition can sometimes seem irrepressible.

But the truth is that competition has often failed to bloom, even when one might have expected it. If I run a bus service at 20 and 50 minutes past the hour, then a competitor can grab my business without competing on price by running a service at 19 and 49 minutes past the hour. Customers will not be well served by that.

Meanwhile electricity and phone companies offer bewildering tariffs, and it is hard to see how water companies will ever truly compete with each other; the logic of geography suggests otherwise.

All this matters because the broad lesson of the great privatisation experiment is that it has worked well when competition has been unleashed, but less well when a government-run business has been replaced by a government-regulated monopoly.

A few years ago, the economist David Parker assembled a survey of post-privatisation performance studies. The most striking thing is the diversity of results. Sometimes productivity soared. Sometimes investors and managers skimmed off all the cream. Revealingly, performance often leapt in the year or two before privatisation, suggesting that state-owned enterprises could be well-run when the political will existed — but that political will was often absent.

My overall reading of the evidence is that privatisation tended to improve profitability, productivity and pricing — but the gains were neither vast nor guaranteed. Electricity privatisation was a success; water privatisation was a disappointment. Privatised railways now serve vastly more passengers than British Rail did. That is a success story but it looks like a failure every time your nose is crushed up against someone’s armpit on the 18:09 from London Victoria.

The evidence suggests this conclusion: the picture is mixed, the details matter, and you can get results if you get the execution right. Our politicians offer a different conclusion: the picture is stark, the details are irrelevant, and we metaphorically execute not our policies but our opponents. The pendulum swings — but shows no sign of pausing in the centre.

Tim Harford in The Financial Times

Political fashions can change quickly, as a glance at almost any western democracy will tell you. The pendulum of the politically possible swings back and forth. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the debates over privatisation and nationalisation.

In the late 1940s, experts advocated nationalisation on a scale hard to imagine today. Arthur Lewis thought the government should run the phone system, insurance and the car industry. James Meade wanted to socialise iron, steel and chemicals; both men later won Nobel memorial prizes in economics.

They were in tune with the times: the British government ended up owning not only utilities and heavy industry but airlines, travel agents and even the removal company, Pickfords. The pendulum swung back in the 1980s and early 1990s, as Margaret Thatcher and John Major began an ever more ambitious series of privatisations, concluding with water, electricity and the railways. The world watched, and often followed suit.

Was it all worth it? The question arises because the pendulum is swinging back again: Jeremy Corbyn, the bookies’ favourite to be the next UK prime minister, wants to renationalise the railways, electricity, water and gas. (He has not yet mentioned Pickfords.) Furthermore, he cites these ambitions as a reason to withdraw from the European single market.

Privatisation’s proponents mention the galvanising effect of the profit motive, or the entrepreneurial spirit of private enterprise. Opponents talk of fat cats and selling off the family silver

That is odd, since there is nothing in single market rules to prevent state ownership of railways and utilities — the excuse seems to be yet another Eurosceptic myth, the leftwing reflection of rightwing tabloids moaning about banana regulation. Since the entire British political class has lost its mind over Brexit, it would be unfair to single out Mr Corbyn on those grounds.

Still, he has reopened a debate that long seemed settled, and piqued my interest. Did privatisation work? Proponents sometimes mention the galvanising effect of the profit motive, or the entrepreneurial spirit of private enterprise. Opponents talk of fat cats and selling off the family silver. Realists might prefer to look at the evidence, and the ambitious UK programme has delivered plenty of that over the years.

There is no reason for a government to own Pickfords, but the calculus of privatisation is more subtle when it comes to natural monopolies — markets that are broadly immune to competition. If I am not satisfied with what Pickford’s has to offer me when I move home, I am not short of options. But the same is not true of the Royal Mail: if I want to write to my MP then the big red pillar box at the end of the street is really the only game in town.

Competition does sometimes emerge in unlikely seeming circumstances. British Telecom seemed to have an iron grip on telephone services in the UK — as did AT&T in the US. The grip melted away in the face of regulation and, more importantly, technological change.

Railways seem like a natural monopoly, yet there are two separate railway lines from my home town of Oxford into London, and two separate railway companies will sell me tickets for the journey. They compete with two bus companies; competition can sometimes seem irrepressible.

But the truth is that competition has often failed to bloom, even when one might have expected it. If I run a bus service at 20 and 50 minutes past the hour, then a competitor can grab my business without competing on price by running a service at 19 and 49 minutes past the hour. Customers will not be well served by that.

Meanwhile electricity and phone companies offer bewildering tariffs, and it is hard to see how water companies will ever truly compete with each other; the logic of geography suggests otherwise.

All this matters because the broad lesson of the great privatisation experiment is that it has worked well when competition has been unleashed, but less well when a government-run business has been replaced by a government-regulated monopoly.

A few years ago, the economist David Parker assembled a survey of post-privatisation performance studies. The most striking thing is the diversity of results. Sometimes productivity soared. Sometimes investors and managers skimmed off all the cream. Revealingly, performance often leapt in the year or two before privatisation, suggesting that state-owned enterprises could be well-run when the political will existed — but that political will was often absent.

My overall reading of the evidence is that privatisation tended to improve profitability, productivity and pricing — but the gains were neither vast nor guaranteed. Electricity privatisation was a success; water privatisation was a disappointment. Privatised railways now serve vastly more passengers than British Rail did. That is a success story but it looks like a failure every time your nose is crushed up against someone’s armpit on the 18:09 from London Victoria.

The evidence suggests this conclusion: the picture is mixed, the details matter, and you can get results if you get the execution right. Our politicians offer a different conclusion: the picture is stark, the details are irrelevant, and we metaphorically execute not our policies but our opponents. The pendulum swings — but shows no sign of pausing in the centre.

Wednesday, 27 September 2017

Monday, 25 September 2017

Dead Cats - Fatal attraction of fake facts sours political debate

Tim Harford in The Financial Times

He did it again: Boris Johnson, UK foreign secretary, exhumed the old referendum-campaign lie that leaving the EU would free up £350m a week for the National Health Service. I think we can skip the well-worn details, because while the claim is misleading, its main purpose is not to mislead but to distract. The growing popularity of this tactic should alarm anyone who thinks that the truth still matters.

He did it again: Boris Johnson, UK foreign secretary, exhumed the old referendum-campaign lie that leaving the EU would free up £350m a week for the National Health Service. I think we can skip the well-worn details, because while the claim is misleading, its main purpose is not to mislead but to distract. The growing popularity of this tactic should alarm anyone who thinks that the truth still matters.

You don’t need to take my word for it that distraction is the goal. A few years ago, a cynical commentator described the “dead cat” strategy, to be deployed when losing an argument at a dinner party: throw a dead cat on the table. The awkward argument will instantly cease, and everyone will start losing their minds about the cat. The cynic’s name was Boris Johnson.

The tactic worked perfectly in the Brexit referendum campaign. Instead of a discussion of the merits and disadvantages of EU membership, we had a frenzied dead-cat debate over the true scale of EU membership fees. Without the steady repetition of a demonstrably false claim, the debate would have run out of oxygen and we might have enjoyed a discussion of the issues instead.

My point is not to refight the referendum campaign. (Mr Johnson would like to, which itself is telling.) There’s more at stake here than Brexit: bold lies have become the dead cat of modern politics on both sides of the Atlantic. Too many politicians have discovered the attractions of the flamboyant falsehood — and why not? The most prominent of them sits in the White House. Dramatic lies do not always persuade, but they do tend to change the subject — and that is often enough.

It is hard to overstate how corrosive this development is. Reasoned conversation becomes impossible; the debaters hardly have time to clear their throats before a fly-blown moggie hits the table with a rancid thud.

Nor is it easy to neutralise a big, politicised lie. Trustworthy nerds can refute it, of course: the fact-checkers, the independent think-tanks, or statutory bodies such as the UK Statistics Authority. But a politician who is unafraid to lie is also unafraid to smear these organisations with claims of bias or corruption — and then one problem has become two. The Statistics Authority and other watchdogs need to guard jealously their reputation for truthfulness; the politicians they contradict often have no such reputation to worry about.

Researchers have been studying the problem for years, after noting how easily charlatans could debase the discussion of smoking, vaccination and climate change. A good starting point is The Debunking Handbook by John Cook and Stephan Lewandowsky, which summarises a dispiriting set of discoveries.

One problem that fact-checkers face is the “familiarity effect”: the endless arguments over the £350m-a-week lie (or Barack Obama’s birthplace, or the number of New Jersey residents who celebrated the destruction of the World Trade Center) is that the very process of rebutting the falsehood ensures that it is repeated over and over again. Even someone who accepts that the lie is a lie would find it much easier to remember than the truth.

A second obstacle is the “backfire effect”. My son is due to get a flu vaccine this week, and some parents at his school are concerned that the flu vaccine may cause flu. It doesn’t. But in explaining that I risk triggering other concerns: who can trust Big Pharma these days? Shouldn’t kids be a bit older before being exposed to these strange chemicals? Some (not all) studies suggest that the process of refuting the narrow concern can actually harden the broader worldview behind it.

Dan Kahan, professor of law and psychology at Yale, points out that issues such as vaccination or climate change — or for that matter, the independence of the UK Statistics Authority — do not become politicised by accident. They are dragged into the realm of polarised politics because it suits some political entrepreneur to do so. For a fleeting partisan advantage, Donald Trump has falsely claimed that vaccines cause autism. Children will die as a result. And once the intellectual environment has become polluted and polarised in this way, it’s extraordinarily difficult to draw the poison out again.

This is a damaging game indeed. All of us tend to think tribally about politics: we absorb the opinions of those around us. But tribal thinking pushes us to be not only a Republican but also a Republican and a vaccine sceptic. One cannot be just for Brexit; one must be for Brexit and against the UK Statistics Authority. Of course it is possible to resist such all-encompassing polarisation, and many people do. But the pull of tribal thinking on all of us is strong.

There are defences against the dead cat strategy. With skill, a fact-check may debunk a false claim without accidentally reinforcing it. But the strongest defence is an electorate that cares, that has more curiosity about the way the world really works than about cartoonish populists. If we let politicians drag facts into their swamp, we are letting them tug at democracy’s foundations.

Tuesday, 19 September 2017

If engineers are allowed to rule the world....

How technology is making our minds redundant.

Franklin Foer in The Guardian

All the values that Silicon Valley professes are the values of the 60s. The big tech companies present themselves as platforms for personal liberation. Everyone has the right to speak their mind on social media, to fulfil their intellectual and democratic potential, to express their individuality. Where television had been a passive medium that rendered citizens inert, Facebook is participatory and empowering. It allows users to read widely, think for themselves and form their own opinions.

We can’t entirely dismiss this rhetoric. There are parts of the world, even in the US, where Facebook emboldens citizens and enables them to organise themselves in opposition to power. But we shouldn’t accept Facebook’s self-conception as sincere, either. Facebook is a carefully managed top-down system, not a robust public square. It mimics some of the patterns of conversation, but that’s a surface trait.

In reality, Facebook is a tangle of rules and procedures for sorting information, rules devised by the corporation for the ultimate benefit of the corporation. Facebook is always surveilling users, always auditing them, using them as lab rats in its behavioural experiments. While it creates the impression that it offers choice, in truth Facebook paternalistically nudges users in the direction it deems best for them, which also happens to be the direction that gets them thoroughly addicted. It’s a phoniness that is most obvious in the compressed, historic career of Facebook’s mastermind.

Mark Zuckerberg is a good boy, but he wanted to be bad, or maybe just a little bit naughty. The heroes of his adolescence were the original hackers. These weren’t malevolent data thieves or cyberterrorists. Zuckerberg’s hacker heroes were disrespectful of authority. They were technically virtuosic, infinitely resourceful nerd cowboys, unbound by conventional thinking. In the labs of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) during the 60s and 70s, they broke any rule that interfered with building the stuff of early computing, such marvels as the first video games and word processors. With their free time, they played epic pranks, which happened to draw further attention to their own cleverness – installing a living cow on the roof of a Cambridge dorm; launching a weather balloon, which miraculously emerged from beneath the turf, emblazoned with “MIT”, in the middle of a Harvard-Yale football game.

The hackers’ archenemies were the bureaucrats who ran universities, corporations and governments. Bureaucrats talked about making the world more efficient, just like the hackers. But they were really small-minded paper-pushers who fiercely guarded the information they held, even when that information yearned to be shared. When hackers clearly engineered better ways of doing things – a box that enabled free long-distance calls, an instruction that might improve an operating system – the bureaucrats stood in their way, wagging an unbending finger. The hackers took aesthetic and comic pleasure in outwitting the men in suits.

When Zuckerberg arrived at Harvard in the fall of 2002, the heyday of the hackers had long passed. They were older guys now, the stuff of good tales, some stuck in twilight struggles against The Man. But Zuckerberg wanted to hack, too, and with that old-time indifference to norms. In high school he picked the lock that prevented outsiders from fiddling with AOL’s code and added his own improvements to its instant messaging program. As a college sophomore he hatched a site called Facemash – with the high-minded purpose of determining the hottest kid on campus. Zuckerberg asked users to compare images of two students and then determine the better-looking of the two. The winner of each pairing advanced to the next round of his hormonal tournament. To cobble this site together, Zuckerberg needed photos. He purloined those from the servers of the various Harvard houses. “One thing is certain,” he wrote on a blog as he put the finishing touches on his creation, “and it’s that I’m a jerk for making this site. Oh well.”

His brief experimentation with rebellion ended with his apologising to a Harvard disciplinary panel, as well as to campus women’s groups, and mulling strategies to redeem his soiled reputation. In the years since, he has shown that defiance really wasn’t his natural inclination. His distrust of authority was such that he sought out Don Graham, then the venerable chairman of the Washington Post company, as his mentor. After he started Facebook, he shadowed various giants of corporate America so that he could study their managerial styles up close.

Still, Zuckerberg’s juvenile fascination with hackers never died – or rather, he carried it forward into his new, more mature incarnation. When he finally had a corporate campus of his own, he procured a vanity address for it: One Hacker Way. He designed a plaza with the word “HACK” inlaid into the concrete. In the centre of his office park, he created an open meeting space called Hacker Square. This is, of course, the venue where his employees join for all-night Hackathons. As he told a group of would-be entrepreneurs, “We’ve got this whole ethos that we want to build a hacker culture.”

Plenty of companies have similarly appropriated hacker culture – hackers are the ur-disrupters – but none have gone as far as Facebook. By the time Zuckerberg began extolling the virtues of hacking, he had stripped the name of most of its original meaning and distilled it into a managerial philosophy that contains barely a hint of rebelliousness. Hackers, he told one interviewer, were “just this group of computer scientists who were trying to quickly prototype and see what was possible. That’s what I try to encourage our engineers to do here.” To hack is to be a good worker, a responsible Facebook citizen – a microcosm of the way in which the company has taken the language of radical individualism and deployed it in the service of conformism.

Zuckerberg claimed to have distilled that hacker spirit into a motivational motto: “Move fast and break things.” The truth is that Facebook moved faster than Zuckerberg could ever have imagined. His company was, as we all know, a dorm-room lark, a thing he ginned up in a Red Bull–induced fit of sleeplessness. As his creation grew, it needed to justify its new scale to its investors, to its users, to the world. It needed to grow up fast. Over the span of its short life, the company has caromed from self-description to self-description. It has called itself a tool, a utility and a platform. It has talked about openness and connectedness. And in all these attempts at defining itself, it has managed to clarify its intentions.

Facebook creators Mark Zuckerberg and Chris Hughes at Harvard in May 2004. Photograph: Rick Friedman/Corbis via Getty

Facebook creators Mark Zuckerberg and Chris Hughes at Harvard in May 2004. Photograph: Rick Friedman/Corbis via Getty

Though Facebook will occasionally talk about the transparency of governments and corporations, what it really wants to advance is the transparency of individuals – or what it has called, at various moments, “radical transparency” or “ultimate transparency”. The theory holds that the sunshine of sharing our intimate details will disinfect the moral mess of our lives. With the looming threat that our embarrassing information will be broadcast, we’ll behave better. And perhaps the ubiquity of incriminating photos and damning revelations will prod us to become more tolerant of one another’s sins. “The days of you having a different image for your work friends or co-workers and for the other people you know are probably coming to an end pretty quickly,” Zuckerberg has said. “Having two identities for yourself is an example of a lack of integrity.”

The point is that Facebook has a strong, paternalistic view on what’s best for you, and it’s trying to transport you there. “To get people to this point where there’s more openness – that’s a big challenge. But I think we’ll do it,” Zuckerberg has said. He has reason to believe that he will achieve that goal. With its size, Facebook has amassed outsized powers. “In a lot of ways Facebook is more like a government than a traditional company,” Zuckerberg has said. “We have this large community of people, and more than other technology companies we’re really setting policies.”

Without knowing it, Zuckerberg is the heir to a long political tradition. Over the last 200 years, the west has been unable to shake an abiding fantasy, a dream sequence in which we throw out the bum politicians and replace them with engineers – rule by slide rule. The French were the first to entertain this notion in the bloody, world-churning aftermath of their revolution. A coterie of the country’s most influential philosophers (notably, Henri de Saint-Simon and Auguste Comte) were genuinely torn about the course of the country. They hated all the old ancient bastions of parasitic power – the feudal lords, the priests and the warriors – but they also feared the chaos of the mob. To split the difference, they proposed a form of technocracy – engineers and assorted technicians would rule with beneficent disinterestedness. Engineers would strip the old order of its power, while governing in the spirit of science. They would impose rationality and order.

This dream has captivated intellectuals ever since, especially Americans. The great sociologist Thorstein Veblen was obsessed with installing engineers in power and, in 1921, wrote a book making his case. His vision briefly became a reality. In the aftermath of the first world war, American elites were aghast at all the irrational impulses unleashed by that conflict – the xenophobia, the racism, the urge to lynch and riot. And when the realities of economic life had grown so complicated, how could politicians possibly manage them? Americans of all persuasions began yearning for the salvific ascendance of the most famous engineer of his time: Herbert Hoover. In 1920, Franklin D Roosevelt – who would, of course, go on to replace him in 1932 – organised a movement to draft Hoover for the presidency.

The Hoover experiment, in the end, hardly realised the happy fantasies about the Engineer King. A very different version of this dream, however, has come to fruition, in the form of the CEOs of the big tech companies. We’re not ruled by engineers, not yet, but they have become the dominant force in American life – the highest, most influential tier of our elite.

There’s another way to describe this historical progression. Automation has come in waves. During the industrial revolution, machinery replaced manual workers. At first, machines required human operators. Over time, machines came to function with hardly any human intervention. For centuries, engineers automated physical labour; our new engineering elite has automated thought. They have perfected technologies that take over intellectual processes, that render the brain redundant. Or, as the former Google and Yahoo executive Marissa Mayer once argued, “You have to make words less human and more a piece of the machine.” Indeed, we have begun to outsource our intellectual work to companies that suggest what we should learn, the topics we should consider, and the items we ought to buy. These companies can justify their incursions into our lives with the very arguments that Saint-Simon and Comte articulated: they are supplying us with efficiency; they are imposing order on human life.

Nobody better articulates the modern faith in engineering’s power to transform society than Zuckerberg. He told a group of software developers, “You know, I’m an engineer, and I think a key part of the engineering mindset is this hope and this belief that you can take any system that’s out there and make it much, much better than it is today. Anything, whether it’s hardware or software, a company, a developer ecosystem – you can take anything and make it much, much better.” The world will improve, if only Zuckerberg’s reason can prevail – and it will.

The precise source of Facebook’s power is algorithms. That’s a concept repeated dutifully in nearly every story about the tech giants, yet it remains fuzzy at best to users of those sites. From the moment of the algorithm’s invention, it was possible to see its power, its revolutionary potential. The algorithm was developed in order to automate thinking, to remove difficult decisions from the hands of humans, to settle contentious debates.

The essence of the algorithm is entirely uncomplicated. The textbooks compare them to recipes – a series of precise steps that can be followed mindlessly. This is different from equations, which have one correct result. Algorithms merely capture the process for solving a problem and say nothing about where those steps ultimately lead.

These recipes are the crucial building blocks of software. Programmers can’t simply order a computer to, say, search the internet. They must give the computer a set of specific instructions for accomplishing that task. These instructions must take the messy human activity of looking for information and transpose that into an orderly process that can be expressed in code. First do this … then do that. The process of translation, from concept to procedure to code, is inherently reductive. Complex processes must be subdivided into a series of binary choices. There’s no equation to suggest a dress to wear, but an algorithm could easily be written for that – it will work its way through a series of either/or questions (morning or night, winter or summer, sun or rain), with each choice pushing to the next.

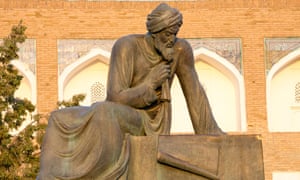

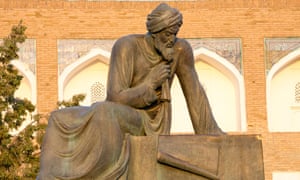

For the first decades of computing, the term “algorithm” wasn’t much mentioned. But as computer science departments began sprouting across campuses in the 60s, the term acquired a new cachet. Its vogue was the product of status anxiety. Programmers, especially in the academy, were anxious to show that they weren’t mere technicians. They began to describe their work as algorithmic, in part because it tied them to one of the greatest of all mathematicians – the Persian polymath Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, or as he was known in Latin, Algoritmi. During the 12th century, translations of al-Khwarizmi introduced Arabic numerals to the west; his treatises pioneered algebra and trigonometry. By describing the algorithm as the fundamental element of programming, the computer scientists were attaching themselves to a grand history. It was a savvy piece of name-dropping: See, we’re not arriviste, we’re working with abstractions and theories, just like the mathematicians!

A statue of the mathematician Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi in Uzbekistan. Photograph: Alamy

A statue of the mathematician Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi in Uzbekistan. Photograph: Alamy

There was sleight of hand in this self-portrayal. The algorithm may be the essence of computer science – but it’s not precisely a scientific concept. An algorithm is a system, like plumbing or a military chain of command. It takes knowhow, calculation and creativity to make a system work properly. But some systems, like some armies, are much more reliable than others. A system is a human artefact, not a mathematical truism. The origins of the algorithm are unmistakably human, but human fallibility isn’t a quality that we associate with it. When algorithms reject a loan application or set the price for an airline flight, they seem impersonal and unbending. The algorithm is supposed to be devoid of bias, intuition, emotion or forgiveness.

Silicon Valley’s algorithmic enthusiasts were immodest about describing the revolutionary potential of their objects of affection. Algorithms were always interesting and valuable, but advances in computing made them infinitely more powerful. The big change was the cost of computing: it collapsed, just as the machines themselves sped up and were tied into a global network. Computers could stockpile massive piles of unsorted data – and algorithms could attack this data to find patterns and connections that would escape human analysts. In the hands of Google and Facebook, these algorithms grew ever more powerful. As they went about their searches, they accumulated more and more data. Their machines assimilated all the lessons of past searches, using these learnings to more precisely deliver the desired results.

For the entirety of human existence, the creation of knowledge was a slog of trial and error. Humans would dream up theories of how the world worked, then would examine the evidence to see whether their hypotheses survived or crashed upon their exposure to reality. Algorithms upend the scientific method – the patterns emerge from the data, from correlations, unguided by hypotheses. They remove humans from the whole process of inquiry. Writing in Wired, Chris Anderson, then editor-in-chief, argued: “We can stop looking for models. We can analyse the data without hypotheses about what it might show. We can throw the numbers into the biggest computing clusters the world has ever seen and let statistical algorithms find patterns where science cannot.”

On one level, this is undeniable. Algorithms can translate languages without understanding words, simply by uncovering the patterns that undergird the construction of sentences. They can find coincidences that humans might never even think to seek. Walmart’s algorithms found that people desperately buy strawberry Pop-Tarts as they prepare for massive storms.

Still, even as an algorithm mindlessly implements its procedures – and even as it learns to see new patterns in the data – it reflects the minds of its creators, the motives of its trainers. Amazon and Netflix use algorithms to make recommendations about books and films. (One-third of purchases on Amazon come from these recommendations.) These algorithms seek to understand our tastes, and the tastes of like-minded consumers of culture. Yet the algorithms make fundamentally different recommendations. Amazon steers you to the sorts of books that you’ve seen before. Netflix directs users to the unfamiliar. There’s a business reason for this difference. Blockbuster movies cost Netflix more to stream. Greater profit arrives when you decide to watch more obscure fare. Computer scientists have an aphorism that describes how algorithms relentlessly hunt for patterns: they talk about torturing the data until it confesses. Yet this metaphor contains unexamined implications. Data, like victims of torture, tells its interrogator what it wants to hear.

Like economics, computer science has its preferred models and implicit assumptions about the world. When programmers are taught algorithmic thinking, they are told to venerate efficiency as a paramount consideration. This is perfectly understandable. An algorithm with an ungainly number of steps will gum up the machinery, and a molasses-like server is a useless one. But efficiency is also a value. When we speed things up, we’re necessarily cutting corners; we’re generalising.

Algorithms can be gorgeous expressions of logical thinking, not to mention a source of ease and wonder. They can track down copies of obscure 19th-century tomes in a few milliseconds; they put us in touch with long-lost elementary school friends; they enable retailers to deliver packages to our doors in a flash. Very soon, they will guide self-driving cars and pinpoint cancers growing in our innards. But to do all these things, algorithms are constantly taking our measure. They make decisions about us and on our behalf. The problem is that when we outsource thinking to machines, we are really outsourcing thinking to the organisations that run the machines.

Mark Zuckerberg disingenuously poses as a friendly critic of algorithms. That’s how he implicitly contrasts Facebook with his rivals across the way at Google. Over in Larry Page’s shop, the algorithm is king – a cold, pulseless ruler. There’s not a trace of life force in its recommendations, and very little apparent understanding of the person keying a query into its engine. Facebook, in his flattering self-portrait, is a respite from this increasingly automated, atomistic world. “Every product you use is better off with your friends,” he says.

What he is referring to is Facebook’s news feed. Here’s a brief explanation for the sliver of humanity who have apparently resisted Facebook: the news feed provides a reverse chronological index of all the status updates, articles and photos that your friends have posted to Facebook. The news feed is meant to be fun, but also geared to solve one of the essential problems of modernity – our inability to sift through the ever-growing, always-looming mounds of information. Who better, the theory goes, to recommend what we should read and watch than our friends? Zuckerberg has boasted that the News Feed turned Facebook into a “personalised newspaper”.

Unfortunately, our friends can do only so much to winnow things for us. Turns out, they like to share a lot. If we just read their musings and followed links to articles, we might be only a little less overwhelmed than before, or perhaps even deeper underwater. So Facebook makes its own choices about what should be read. The company’s algorithms sort the thousands of things a Facebook user could possibly see down to a smaller batch of choice items. And then within those few dozen items, it decides what we might like to read first.

Algorithms are, by definition, invisibilia. But we can usually sense their presence – that somewhere in the distance, we’re interacting with a machine. That’s what makes Facebook’s algorithm so powerful. Many users – 60%, according to the best research – are completely unaware of its existence. But even if they know of its influence, it wouldn’t really matter. Facebook’s algorithm couldn’t be more opaque. It has grown into an almost unknowable tangle of sprawl. The algorithm interprets more than 100,000 “signals” to make its decisions about what users see. Some of these signals apply to all Facebook users; some reflect users’ particular habits and the habits of their friends. Perhaps Facebook no longer fully understands its own tangle of algorithms – the code, all 60m lines of it, is a palimpsest, where engineers add layer upon layer of new commands.

Pondering the abstraction of this algorithm, imagine one of those earliest computers with its nervously blinking lights and long rows of dials. To tweak the algorithm, the engineers turn the knob a click or two. The engineers are constantly making small adjustments here and there, so that the machine performs to their satisfaction. With even the gentlest caress of the metaphorical dial, Facebook changes what its users see and read. It can make our friends’ photos more or less ubiquitous; it can punish posts filled with self-congratulatory musings and banish what it deems to be hoaxes; it can promote video rather than text; it can favour articles from the likes of the New York Times or BuzzFeed, if it so desires. Or if we want to be melodramatic about it, we could say Facebook is constantly tinkering with how its users view the world – always tinkering with the quality of news and opinion that it allows to break through the din, adjusting the quality of political and cultural discourse in order to hold the attention of users for a few more beats.

But how do the engineers know which dial to twist and how hard? There’s a whole discipline, data science, to guide the writing and revision of algorithms. Facebook has a team, poached from academia, to conduct experiments on users. It’s a statistician’s sexiest dream – some of the largest data sets in human history, the ability to run trials on mathematically meaningful cohorts. When Cameron Marlow, the former head of Facebook’s data science team, described the opportunity, he began twitching with ecstatic joy. “For the first time,” Marlow said, “we have a microscope that not only lets us examine social behaviour at a very fine level that we’ve never been able to see before, but allows us to run experiments that millions of users are exposed to.” Facebook’s headquarters in Menlo Park, California. Photograph: Alamy

Facebook’s headquarters in Menlo Park, California. Photograph: Alamy

Facebook likes to boast about the fact of its experimentation more than the details of the actual experiments themselves. But there are examples that have escaped the confines of its laboratories. We know, for example, that Facebook sought to discover whether emotions are contagious. To conduct this trial, Facebook attempted to manipulate the mental state of its users. For one group, Facebook excised the positive words from the posts in the news feed; for another group, it removed the negative words. Each group, it concluded, wrote posts that echoed the mood of the posts it had reworded. This study was roundly condemned as invasive, but it is not so unusual. As one member of Facebook’s data science team confessed: “Anyone on that team could run a test. They’re always trying to alter people’s behaviour.”

There’s no doubting the emotional and psychological power possessed by Facebook – or, at least, Facebook doesn’t doubt it. It has bragged about how it increased voter turnout (and organ donation) by subtly amping up the social pressures that compel virtuous behaviour. Facebook has even touted the results from these experiments in peer-reviewed journals: “It is possible that more of the 0.60% growth in turnout between 2006 and 2010 might have been caused by a single message on Facebook,” said one study published in Nature in 2012. No other company has made such claims about its ability to shape democracy like this – and for good reason. It’s too much power to entrust to a corporation.

The many Facebook experiments add up. The company believes that it has unlocked social psychology and acquired a deeper understanding of its users than they possess of themselves. Facebook can predict users’ race, sexual orientation, relationship status and drug use on the basis of their “likes” alone. It’s Zuckerberg’s fantasy that this data might be analysed to uncover the mother of all revelations, “a fundamental mathematical law underlying human social relationships that governs the balance of who and what we all care about”. That is, of course, a goal in the distance. In the meantime, Facebook will keep probing – constantly testing to see what we crave and what we ignore, a never-ending campaign to improve Facebook’s capacity to give us the things that we want and things we don’t even know we want. Whether the information is true or concocted, authoritative reporting or conspiratorial opinion, doesn’t really seem to matter much to Facebook. The crowd gets what it wants and deserves.

The automation of thinking: we’re in the earliest days of this revolution, of course. But we can see where it’s heading. Algorithms have retired many of the bureaucratic, clerical duties once performed by humans – and they will soon begin to replace more creative tasks. At Netflix, algorithms suggest the genres of movies to commission. Some news wires use algorithms to write stories about crime, baseball games and earthquakes – the most rote journalistic tasks. Algorithms have produced fine art and composed symphonic music, or at least approximations of them.

It’s a terrifying trajectory, especially for those of us in these lines of work. If algorithms can replicate the process of creativity, then there’s little reason to nurture human creativity. Why bother with the tortuous, inefficient process of writing or painting if a computer can produce something seemingly as good and in a painless flash? Why nurture the overinflated market for high culture when it could be so abundant and cheap? No human endeavour has resisted automation, so why should creative endeavours be any different?

The engineering mindset has little patience for the fetishisation of words and images, for the mystique of art, for moral complexity or emotional expression. It views humans as data, components of systems, abstractions. That’s why Facebook has so few qualms about performing rampant experiments on its users. The whole effort is to make human beings predictable – to anticipate their behaviour, which makes them easier to manipulate. With this sort of cold-blooded thinking, so divorced from the contingency and mystery of human life, it’s easy to see how long-standing values begin to seem like an annoyance – why a concept such as privacy would carry so little weight in the engineer’s calculus, why the inefficiencies of publishing and journalism seem so imminently disruptable.

Facebook would never put it this way, but algorithms are meant to erode free will, to relieve humans of the burden of choosing, to nudge them in the right direction. Algorithms fuel a sense of omnipotence, the condescending belief that our behaviour can be altered, without our even being aware of the hand guiding us, in a superior direction. That’s always been a danger of the engineering mindset, as it moves beyond its roots in building inanimate stuff and begins to design a more perfect social world. We are the screws and rivets in the grand design.

Franklin Foer in The Guardian

All the values that Silicon Valley professes are the values of the 60s. The big tech companies present themselves as platforms for personal liberation. Everyone has the right to speak their mind on social media, to fulfil their intellectual and democratic potential, to express their individuality. Where television had been a passive medium that rendered citizens inert, Facebook is participatory and empowering. It allows users to read widely, think for themselves and form their own opinions.

We can’t entirely dismiss this rhetoric. There are parts of the world, even in the US, where Facebook emboldens citizens and enables them to organise themselves in opposition to power. But we shouldn’t accept Facebook’s self-conception as sincere, either. Facebook is a carefully managed top-down system, not a robust public square. It mimics some of the patterns of conversation, but that’s a surface trait.

In reality, Facebook is a tangle of rules and procedures for sorting information, rules devised by the corporation for the ultimate benefit of the corporation. Facebook is always surveilling users, always auditing them, using them as lab rats in its behavioural experiments. While it creates the impression that it offers choice, in truth Facebook paternalistically nudges users in the direction it deems best for them, which also happens to be the direction that gets them thoroughly addicted. It’s a phoniness that is most obvious in the compressed, historic career of Facebook’s mastermind.

Mark Zuckerberg is a good boy, but he wanted to be bad, or maybe just a little bit naughty. The heroes of his adolescence were the original hackers. These weren’t malevolent data thieves or cyberterrorists. Zuckerberg’s hacker heroes were disrespectful of authority. They were technically virtuosic, infinitely resourceful nerd cowboys, unbound by conventional thinking. In the labs of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) during the 60s and 70s, they broke any rule that interfered with building the stuff of early computing, such marvels as the first video games and word processors. With their free time, they played epic pranks, which happened to draw further attention to their own cleverness – installing a living cow on the roof of a Cambridge dorm; launching a weather balloon, which miraculously emerged from beneath the turf, emblazoned with “MIT”, in the middle of a Harvard-Yale football game.

The hackers’ archenemies were the bureaucrats who ran universities, corporations and governments. Bureaucrats talked about making the world more efficient, just like the hackers. But they were really small-minded paper-pushers who fiercely guarded the information they held, even when that information yearned to be shared. When hackers clearly engineered better ways of doing things – a box that enabled free long-distance calls, an instruction that might improve an operating system – the bureaucrats stood in their way, wagging an unbending finger. The hackers took aesthetic and comic pleasure in outwitting the men in suits.

When Zuckerberg arrived at Harvard in the fall of 2002, the heyday of the hackers had long passed. They were older guys now, the stuff of good tales, some stuck in twilight struggles against The Man. But Zuckerberg wanted to hack, too, and with that old-time indifference to norms. In high school he picked the lock that prevented outsiders from fiddling with AOL’s code and added his own improvements to its instant messaging program. As a college sophomore he hatched a site called Facemash – with the high-minded purpose of determining the hottest kid on campus. Zuckerberg asked users to compare images of two students and then determine the better-looking of the two. The winner of each pairing advanced to the next round of his hormonal tournament. To cobble this site together, Zuckerberg needed photos. He purloined those from the servers of the various Harvard houses. “One thing is certain,” he wrote on a blog as he put the finishing touches on his creation, “and it’s that I’m a jerk for making this site. Oh well.”

His brief experimentation with rebellion ended with his apologising to a Harvard disciplinary panel, as well as to campus women’s groups, and mulling strategies to redeem his soiled reputation. In the years since, he has shown that defiance really wasn’t his natural inclination. His distrust of authority was such that he sought out Don Graham, then the venerable chairman of the Washington Post company, as his mentor. After he started Facebook, he shadowed various giants of corporate America so that he could study their managerial styles up close.

Still, Zuckerberg’s juvenile fascination with hackers never died – or rather, he carried it forward into his new, more mature incarnation. When he finally had a corporate campus of his own, he procured a vanity address for it: One Hacker Way. He designed a plaza with the word “HACK” inlaid into the concrete. In the centre of his office park, he created an open meeting space called Hacker Square. This is, of course, the venue where his employees join for all-night Hackathons. As he told a group of would-be entrepreneurs, “We’ve got this whole ethos that we want to build a hacker culture.”

Plenty of companies have similarly appropriated hacker culture – hackers are the ur-disrupters – but none have gone as far as Facebook. By the time Zuckerberg began extolling the virtues of hacking, he had stripped the name of most of its original meaning and distilled it into a managerial philosophy that contains barely a hint of rebelliousness. Hackers, he told one interviewer, were “just this group of computer scientists who were trying to quickly prototype and see what was possible. That’s what I try to encourage our engineers to do here.” To hack is to be a good worker, a responsible Facebook citizen – a microcosm of the way in which the company has taken the language of radical individualism and deployed it in the service of conformism.

Zuckerberg claimed to have distilled that hacker spirit into a motivational motto: “Move fast and break things.” The truth is that Facebook moved faster than Zuckerberg could ever have imagined. His company was, as we all know, a dorm-room lark, a thing he ginned up in a Red Bull–induced fit of sleeplessness. As his creation grew, it needed to justify its new scale to its investors, to its users, to the world. It needed to grow up fast. Over the span of its short life, the company has caromed from self-description to self-description. It has called itself a tool, a utility and a platform. It has talked about openness and connectedness. And in all these attempts at defining itself, it has managed to clarify its intentions.

Facebook creators Mark Zuckerberg and Chris Hughes at Harvard in May 2004. Photograph: Rick Friedman/Corbis via Getty