Tahir Mehdi in The Dawn

A group of Pakistani Dalits in Mirpurkhas gathered at their town hall recently. They vowed to initiate a movement to assert their distinct political identity, and fight for their communities’ rights.

The word ‘dalit’ literally means ‘oppressed people’; it has been in use since the 19th century to describe communities that fall outside of the four-caste Hindu hierarchy. These ‘outcastes’ or ‘untouchables’ have been subject to horrendous discrimination, in all spheres of life, for at least the past 2,000 years.

As political consciousness in undivided India arose towards the end of the British Raj, a number of Dalit leaders emerged to formulate and push forward their own political demands.

Most prolific among them was Dr B.R. Ambedkar, who did not trust the upper-caste-dominated Congress with the political interests and aspirations of his communities. He made a strong case for a separate electorate for Dalits in the 1930-32 Round Table Conferences. The Muslim League had also made the same demand the centre of their politics.

The Communal Award of 1932 accepted the positions of both, but Gandhi persuaded Ambedkar to agree to reserved seats for Dalits within a joint electorate system, rather than having Dalit voters elect Dalit parliamentarians separately.

The Government of India Act, 1935 included a schedule of castes that were subject of its specific clauses. The term ‘Scheduled Castes’ thus replaced ‘Dalits’ in official parlance. In Pakistan, the government also notified 40 castes as ‘Scheduled’ through an ordinance in 1957, which included Bheel, Kohli and Menghwar.

Dalits did establish a distinct identity — but their mobility within politics continued to remain restricted due to entrenched caste barriers.

Dr Ambedkar made it to the Constituent Assembly of India only with the help of fellow Dalit leader, Jogendra Nath Mandal.

Mandal, from East Bengal, belonged to the Namahsudra (an ‘untouchable’) caste. He was long associated with the Muslim League, and had served as a minister in the Suharwardy-led government of Bengal in 1946. Being a Dalit leader, he had found common cause with poor Bengali Muslims fighting against landlords and moneylenders, the majority of whom were upper-caste Hindus.

He supported the creation of Pakistan, and was made temporary chairman of the first Constituent Assembly. He served as a federal minister in the first cabinet.

Mandal’s elevation was perceived as a gesture towards Dalits, indicating that Muslim Pakistan would treat them better than the caste-plagued Hindu Congress. This gesture proved short-lived — and soon turned into a tale of betrayal.

In March 1949, a Dalit member of the first Constituent Assembly motioned to amend the Objectives Resolution to include ‘Scheduled Castes’ in the language which vowed to safeguard interests of minorities. Sardar Abdur Rab Nishtar defended the original phrasing, arguing that specificity was not required; whether Muslim or Hindu, any marginalised community would be protected.

The amendment was turned down, which was a denial of the everyday realities of our society, where oppression is encoded into the caste system.

It became evident that Pakistan divides its population into two groups only — Muslims and non-Muslims — and that when it comes to sharing state resources and privileges, Muslims would benefit from their preferential status at the expense of non-Muslims.

Mandal resigned in 1950. If one is to trust the veracity of his resignation letter available online, he offered a scathing indictment of Pakistan’s failure to safeguard its minorities. He accused the rulers of extreme forms of discrimination against Dalits — including forced conversions and even mass murder. A dejected Mandal moved back to Kolkata. That is how Dalits’ dream of Pakistan turned into a nightmare. But the worst was yet to come.

Gen Zia introduced the separate electorate system, and allotted seats in elected houses to ‘Hindus and Scheduled Castes’. This collating of Dalits and caste Hindus not only stripped Dalits of the distinct political identity they had struggled for, it also pushed them back into the same Hindu fold, against which Mandal and the Muslim League had sided. Zia’s system was later changed, but the succeeding scheme continued to prefer upper-caste Hindus.

This resulted in rich caste Hindus obtaining ruling positions by using Dalits as their ladder. While there is little doubt that the rich in majority communities also get most party posts and parliamentary seats, in the Dalit context this has additional ramifications.

For example, the well-educated, upper-caste, Sindhi Hindus get admissions in higher education institutions on merit, and happen to occupy more seats than their proportion in the population. It makes sense for them not to demand quotas.

The absence of a quota, however, is against the interests of Dalits, who have a poor educational profile and seldom get good jobs. Their quota demands cannot make headway as long as their representatives belong to the upper-caste.

In matters of personal laws, the positions of Dalits and caste Hindus diverge on issues as important as divorce. Marriage cannot be dissolved according to the upper-caste code, but this is not so with Dalits. Upper-caste insistence that Hindu marriage law should not include a divorce clause has been a major impediment in its enactment.

The upper castes are a minuscule minority within Pakistani Hindus, and the vast Dalit electorate is all that democratically legitimises their politics. Yet, no sincere attempt to reach out to them has been made.

Community organisations formed by the upper castes have primarily charitable goals which, of course, do not include ‘annihilation of caste’. Their membership fees are often more than what most Dalits of Thar could ever pay, even with a loan guarantee taken for a lifetime of bonded labour.

Dalits complain bitterly that when an upper-caste girl is forcibly converted, caste Hindus parade the length of Sindh in protest, making headlines. Dalit women, on the other hand, suffer the same ordeal every day, but all they get from their community ‘leaders’ are empty promises.

The Dalit gathering in Mirpurkhas featured a large poster of Dr Ambedkar. Perhaps Mandal’s decision to call it quits on Pakistan was wrong. Pakistani Dalits will have to pick up the pieces of their broken dream, and start from where Mandal left off.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Monday, 9 May 2016

Sunday, 8 May 2016

Offshore finance: more than £12tn siphoned out of emerging countries

Analysis shows £1.3tn of assets from Russia sitting offshore, as David Cameron prepares to host anti-corruption summit.

David Cameron under pressure to end tax haven secrecy

The analysis, carried out by Columbia University professor James S Henry for the Tax Justice Network, shows that by the end of 2014, $1.3tn of assets from Russia were sitting offshore. The figures, which came from compiling and cross-checking data from global institutions including the International Monetary Fund and the United Nations, follow the Panama Papers revelations of global, systemic tax avoidance.

Chinese citizens have $1.2tn stashed away in tax havens, once estimates for Hong Kong and Macau are included. Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia – all of which have seen high-profile corruption scandals in recent years – also come high on the list of the worst-affected countries.

Henry, a former chief economist at consultancy McKinsey, told the Guardian his research underlines the fact that tax-dodging is not the only motivation for using tax havens – criminals and kleptocrats also make prolific use of their services, to keep their wealth secret, and their money safe. He said the list of users of offshore jurisdictions is like the cantina scene in Star Wars, where a motley group of unsavoury intergalactic characters is assembled. Henry said: “It’s like the Star Wars scene: you have the tax dodgers in one corner, the arms dealers in another, the kleptocrats over here. There’s also those using tax havens for money laundering, or fraud.”

Oil-rich countries including Nigeria and Angola feature as key sources of offshore funds, the research finds, as do Brazil and Argentina. Henry said the owners of this hidden capital are often so keen to secure secrecy and avoid their wealth being appropriated back home, that they are willing to accept paltry financial returns rather than investing it in ways that might promote economic development. Charging just 1% tax on this mountain of offshore wealth would yield more than $120bn a year — almost equivalent to the entire $131bn global aid budget.

The TJN is urging Cameron to push for agreement on a series of issues at this week’s summit, including a tougher crackdown on the banks, lawyers and other professionals who facilitate financial secrecy; and an obligation on all politicians to make their personal financial situation transparent.

The prime minister published a summary of his tax affairs last month, after the Panama Papers leaks revealed that his father had set up an investment fund, Blairmore, based in the offshore jurisdiction of Panama.

Henry argued that when senior figures in authoritarian states such as China use tax havens to guard their money safely, they are effectively free-riding on the legal and financial systems of other countries. “All of these felons and kleptocrats are in a way essentially dependent on the rule of law when it comes to protecting their money,” he said.

He said it was not just exotic locations such as the Cayman Islands where money can effectively be hidden, but also some US states, such as Delaware, where it is possible for foreign investors to start up and run a company without making clear its ultimate ownership – something all UK firms will have to do from later this year.

Russian banknotes. A detailed 18-month research project has uncovered a sharp increase in the capital flowing offshore from developing countries, in particular Russia and China. Photograph: Maxim Zmeyev/Reuters

Heather Stewart in The Guardian

More than $12tn (£8tn) has been siphoned out of Russia, China and other emerging economies into the secretive world of offshore finance, new research has revealed, as David Cameron prepares to host world leaders for an anti-corruption summit.

A detailed 18-month research project has uncovered a sharp increase in the capital flowing offshore from developing countries, in particular Russia and China.

Heather Stewart in The Guardian

More than $12tn (£8tn) has been siphoned out of Russia, China and other emerging economies into the secretive world of offshore finance, new research has revealed, as David Cameron prepares to host world leaders for an anti-corruption summit.

A detailed 18-month research project has uncovered a sharp increase in the capital flowing offshore from developing countries, in particular Russia and China.

David Cameron under pressure to end tax haven secrecy

The analysis, carried out by Columbia University professor James S Henry for the Tax Justice Network, shows that by the end of 2014, $1.3tn of assets from Russia were sitting offshore. The figures, which came from compiling and cross-checking data from global institutions including the International Monetary Fund and the United Nations, follow the Panama Papers revelations of global, systemic tax avoidance.

Chinese citizens have $1.2tn stashed away in tax havens, once estimates for Hong Kong and Macau are included. Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia – all of which have seen high-profile corruption scandals in recent years – also come high on the list of the worst-affected countries.

Henry, a former chief economist at consultancy McKinsey, told the Guardian his research underlines the fact that tax-dodging is not the only motivation for using tax havens – criminals and kleptocrats also make prolific use of their services, to keep their wealth secret, and their money safe. He said the list of users of offshore jurisdictions is like the cantina scene in Star Wars, where a motley group of unsavoury intergalactic characters is assembled. Henry said: “It’s like the Star Wars scene: you have the tax dodgers in one corner, the arms dealers in another, the kleptocrats over here. There’s also those using tax havens for money laundering, or fraud.”

Oil-rich countries including Nigeria and Angola feature as key sources of offshore funds, the research finds, as do Brazil and Argentina. Henry said the owners of this hidden capital are often so keen to secure secrecy and avoid their wealth being appropriated back home, that they are willing to accept paltry financial returns rather than investing it in ways that might promote economic development. Charging just 1% tax on this mountain of offshore wealth would yield more than $120bn a year — almost equivalent to the entire $131bn global aid budget.

The TJN is urging Cameron to push for agreement on a series of issues at this week’s summit, including a tougher crackdown on the banks, lawyers and other professionals who facilitate financial secrecy; and an obligation on all politicians to make their personal financial situation transparent.

The prime minister published a summary of his tax affairs last month, after the Panama Papers leaks revealed that his father had set up an investment fund, Blairmore, based in the offshore jurisdiction of Panama.

Henry argued that when senior figures in authoritarian states such as China use tax havens to guard their money safely, they are effectively free-riding on the legal and financial systems of other countries. “All of these felons and kleptocrats are in a way essentially dependent on the rule of law when it comes to protecting their money,” he said.

He said it was not just exotic locations such as the Cayman Islands where money can effectively be hidden, but also some US states, such as Delaware, where it is possible for foreign investors to start up and run a company without making clear its ultimate ownership – something all UK firms will have to do from later this year.

After two years of baby talk, how about some grown-up action?

Shobhaa De in Politically Incorrect | India | TOI

They call them the Terrible Twos. I can confidently confirm that. My neighbour has a cuddly grandson who just turned two. I have been observing him closely — not only because he is their first grandchild, but because, he was born at about the same time a brand new political force came into existence. The grandson took over our hearts. The political force took over the country.

Last year, around this time, I was watching the neighbour’s kid take his first few baby steps. He fell, got up, fell again. I clapped. I encouraged him to try again. I rewarded him with hugs, smiles and kisses. Occasionally, I dangled carrots as incentives. He was cutting his teeth. He was nearly potty-trained. There were a few accidents. But he could tell from our reactions that we wanted our Bharat to be swachh — starting with the drawingroom carpet. We indulged him. Bachche toh bachche hain, we said, as he ran around, refusing to stay put in any one place for long. We noticed he was more willing to make friends with strangers than with his own folks. He’d meet new kids in the garden and promptly invite them home. He was keen to share his favourite toys with padosis but not that keen on sharing the same with his brothers. He liked all the foreign kids he met in the park. And they seemed to like him, too. Except when he hugged them, squeezed them and refused to let go till his pictures were clicked. This led to a few embarrassing situations. While American kids reciprocated, sort of, European bachchas gave him the cold shoulder. Especially, the Italians. We told him not to feel bad. He was too inexperienced to understand how far he could go with foreigners and those bear hugs.

His popularity in the neighbourhood was high. If one overlooked the usual dog-in-the-manger attitude kids display when their playthings are being snatched. Several kids attended his birthday party that first year and everybody had a ball. You see, an elaborate magic show had been orchestrated for the benefit of guests, and the clever magician was busy pulling all sorts of wonderful things out of his hat. The kids were mesmerised and thrilled. They wanted the magician to reveal how he performed all those fantastic tricks making objects — and people — disappear. Of course he didn’t oblige. The kids were most disappointed and started chorusing “Cheater! Cheater!” Kids can be very blunt, and very cruel. Adults are more accommodating. They know exactly the sort of tricks magicians play on gullible audiences.

Then there was the other big problem faced by our two-year-old. He couldn’t — and still can’t — separate fact from fiction, fantasy from reality. In his mind, there is only one version of the truth — his. Idle bystanders accuse us of being intolerant when we try and correct him in public. We are not happy with these interventions, since we believe we are entitled to our opinions when it comes to an obstinate two-year-old who refuses to see reason. But then we are always outnumbered!

Actually, it’s fun being a two-year-old. Zero responsibilities and lots of noise! Two-year-olds are compulsive attention-seekers. They love the spotlight on them and are pretty good at hogging the show. Of course, they are selfish and selfcentred. A toddler gets away with virtually anything! People nod understandingly and say, “Give some more time… be patient. Wait for improvement.” Our little fellow is a fast learner. He knows he has to compete and beat that kid next door. The dimpled cutie who is still a mama’s boy and, gulp… is still learning how to talk. But he has the best toys in the neighbourhood — Italian choppers, etc.

Our kid does talk. But not to us. He prefers to talk to himself. Last week we overheard him muttering “achhe din… achhe din” over and over again. We clapped and patted him on the back. Next week our kid has a big test to clear. It is an entrance exam to get into a good primary school. Stiff competition is posed by aggressive rivals. But our two-year-old is super confident. He has armed himself with a big stick to beat those who stand in his way. Once a brat, always a brat, they say.

They call them the Terrible Twos. I can confidently confirm that. My neighbour has a cuddly grandson who just turned two. I have been observing him closely — not only because he is their first grandchild, but because, he was born at about the same time a brand new political force came into existence. The grandson took over our hearts. The political force took over the country.

Last year, around this time, I was watching the neighbour’s kid take his first few baby steps. He fell, got up, fell again. I clapped. I encouraged him to try again. I rewarded him with hugs, smiles and kisses. Occasionally, I dangled carrots as incentives. He was cutting his teeth. He was nearly potty-trained. There were a few accidents. But he could tell from our reactions that we wanted our Bharat to be swachh — starting with the drawingroom carpet. We indulged him. Bachche toh bachche hain, we said, as he ran around, refusing to stay put in any one place for long. We noticed he was more willing to make friends with strangers than with his own folks. He’d meet new kids in the garden and promptly invite them home. He was keen to share his favourite toys with padosis but not that keen on sharing the same with his brothers. He liked all the foreign kids he met in the park. And they seemed to like him, too. Except when he hugged them, squeezed them and refused to let go till his pictures were clicked. This led to a few embarrassing situations. While American kids reciprocated, sort of, European bachchas gave him the cold shoulder. Especially, the Italians. We told him not to feel bad. He was too inexperienced to understand how far he could go with foreigners and those bear hugs.

His popularity in the neighbourhood was high. If one overlooked the usual dog-in-the-manger attitude kids display when their playthings are being snatched. Several kids attended his birthday party that first year and everybody had a ball. You see, an elaborate magic show had been orchestrated for the benefit of guests, and the clever magician was busy pulling all sorts of wonderful things out of his hat. The kids were mesmerised and thrilled. They wanted the magician to reveal how he performed all those fantastic tricks making objects — and people — disappear. Of course he didn’t oblige. The kids were most disappointed and started chorusing “Cheater! Cheater!” Kids can be very blunt, and very cruel. Adults are more accommodating. They know exactly the sort of tricks magicians play on gullible audiences.

Then there was the other big problem faced by our two-year-old. He couldn’t — and still can’t — separate fact from fiction, fantasy from reality. In his mind, there is only one version of the truth — his. Idle bystanders accuse us of being intolerant when we try and correct him in public. We are not happy with these interventions, since we believe we are entitled to our opinions when it comes to an obstinate two-year-old who refuses to see reason. But then we are always outnumbered!

Actually, it’s fun being a two-year-old. Zero responsibilities and lots of noise! Two-year-olds are compulsive attention-seekers. They love the spotlight on them and are pretty good at hogging the show. Of course, they are selfish and selfcentred. A toddler gets away with virtually anything! People nod understandingly and say, “Give some more time… be patient. Wait for improvement.” Our little fellow is a fast learner. He knows he has to compete and beat that kid next door. The dimpled cutie who is still a mama’s boy and, gulp… is still learning how to talk. But he has the best toys in the neighbourhood — Italian choppers, etc.

Our kid does talk. But not to us. He prefers to talk to himself. Last week we overheard him muttering “achhe din… achhe din” over and over again. We clapped and patted him on the back. Next week our kid has a big test to clear. It is an entrance exam to get into a good primary school. Stiff competition is posed by aggressive rivals. But our two-year-old is super confident. He has armed himself with a big stick to beat those who stand in his way. Once a brat, always a brat, they say.

India ranks ninth in crony-capitalism index

PTI in Times of India

India is ranked ninth in crony-capitalism with crony sector wealth accounting for 3.4 per cent of the gross domestic product (GDP), according to a new study by The Economist.

In India, the non-crony sector wealth amounts to 8.3 per cent of the GDP, as per the latest crony-capitalism index.

In 2014 rankings too, India stood at the ninth place.

Using data from a list of the world's billionaires and their worth published by Forbes, each individual is labelled as crony or not based on the source of their wealth.

Germany is cleanest, where just a sliver of the country's billionaires derive their wealth from crony sectors.

Russia fares worst in the index, wealth from the country's crony sectors amounts to 18 per cent of its GDP, it said.

Russia tops the list followed by Malaysia, the Philippines and Singapore.

"Thanks to tumbling energy and commodity prices politically connected tycoons have been feeling the squeeze in recent years," the study said.

Among the 22 economies in the index, crony wealth has fallen by USD 116 billion since 2014.

"But as things stand, if commodity prices rebound, crony capitalists wealth is sure to rise again," it added.

The past 20 years have been a golden age for crony capitalists--tycoons active in industries where chumminess with government is part of the game.

Their combined fortunes have dropped 16 per cent since 2014, according to The Economist updated crony-capitalism index.

"One reason is the commodity crash. Another is a backlash from the middle class," it said.

Worldwide, the worth of billionaires in crony industries soared by 385 per cent between 2004 and 2014 to USD 2 trillion, it added.

India is ranked ninth in crony-capitalism with crony sector wealth accounting for 3.4 per cent of the gross domestic product (GDP), according to a new study by The Economist.

In India, the non-crony sector wealth amounts to 8.3 per cent of the GDP, as per the latest crony-capitalism index.

In 2014 rankings too, India stood at the ninth place.

Using data from a list of the world's billionaires and their worth published by Forbes, each individual is labelled as crony or not based on the source of their wealth.

Germany is cleanest, where just a sliver of the country's billionaires derive their wealth from crony sectors.

Russia fares worst in the index, wealth from the country's crony sectors amounts to 18 per cent of its GDP, it said.

Russia tops the list followed by Malaysia, the Philippines and Singapore.

"Thanks to tumbling energy and commodity prices politically connected tycoons have been feeling the squeeze in recent years," the study said.

Among the 22 economies in the index, crony wealth has fallen by USD 116 billion since 2014.

"But as things stand, if commodity prices rebound, crony capitalists wealth is sure to rise again," it added.

The past 20 years have been a golden age for crony capitalists--tycoons active in industries where chumminess with government is part of the game.

Their combined fortunes have dropped 16 per cent since 2014, according to The Economist updated crony-capitalism index.

"One reason is the commodity crash. Another is a backlash from the middle class," it said.

Worldwide, the worth of billionaires in crony industries soared by 385 per cent between 2004 and 2014 to USD 2 trillion, it added.

Saturday, 7 May 2016

Is it science or theology?

Pervez Hoodbhoy in The Dawn

When Pakistani students open a physics or biology textbook, it is sometimes unclear whether they are actually learning science or, instead, theology. The reason: every science textbook, published by a government-run textbook board in Pakistan, by law must contain in its first chapter how Allah made our world, as well as how Muslims and Pakistanis have created science.

I have no problem with either. But the first properly belongs to Islamic Studies, the second to Islamic or Pakistani history. Neither legitimately belongs to a textbook on a modern-day scientific subject. That’s because religion and science operate very differently and have widely different assumptions. Religion is based on belief and requires the existence of a hereafter, whereas science worries only about the here and now.

Demanding that science and faith be tied together has resulted in national bewilderment and mass intellectual enfeeblement. Millions of Pakistanis have studied science subjects in school and then gone on to study technical, science-based subjects in college and university. And yet most — including science teachers — would flunk if given even the simplest science quiz.

How did this come about? Let’s take a quick browse through a current 10th grade physics book. The introductory section has the customary holy verses. These are followed by a comical overview of the history of physics. Newton and Einstein — the two greatest names — are unmentioned. Instead there’s Ptolemy the Greek, Al-Kindi, Al-Beruni, Ibn-e-Haytham, A.Q. Khan, and — amusingly — the heretical Abdus Salam.

The end-of-chapter exercises test the mettle of students with such questions as: Mark true/false; A) The first revelation sent to the Holy Prophet (PBUH) was about the creation of Heaven? B) The pin-hole camera was invented by Ibn-e-Haytham? C) Al-Beruni declared that Sind was an underwater valley that gradually filled with sand? D) Islam teaches that only men must acquire knowledge?

Dear Reader: You may well gasp in disbelief, or just hold your head in despair. How could Pakistan’s collective intelligence and the quality of what we teach our children have sunk so low? To see more such questions, or to check my translation from Urdu into English, please visit the websitehttp://eacpe.org/ where relevant pages from the above text (as well as from those discussed below) have been scanned and posted.

Take another physics book — this one (English) is for sixth-grade students. It makes abundantly clear its discomfort with the modern understanding of our universe’s beginning. The theory of the Big Bang is attributed to “a priest, George Lamaitre [sic] of Belgium”. The authors cunningly mention his faith hoping to discredit his science. Continuing, they declare that “although the Big Bang Theory is widely accepted, it probably will never be proved”.

While Georges Lemaître was indeed a Catholic priest, he was so much more. A professor of physics, he worked out the expanding universe solution to Einstein’s equations. Lemaître insisted on separating science from religion; he had publicly chided Pope Pius XII when the pontiff grandly declared that Lemaître’s results provided a scientific validation to Catholicism.

Local biology books are even more schizophrenic and confusing than the physics ones. A 10th-grade book starts off its section on ‘Life and its Origins’ unctuously quoting one religious verse after another. None of these verses hint towards evolution, and many Muslims believe that evolution is counter-religious. Then, suddenly, a full page annotated chart hits you in the face. Stolen from some modern biology book written in some other part of the world, it depicts various living organisms evolving into apes and then into modern humans. Ouch!

Such incoherent babble confuses the nature of science — its history, purpose, method, and fundamental content. If the authors are confused, just imagine the impact on students who must learn this stuff. What weird ideas must inhabit their minds!

Compounding scientific ignorance is prejudice. Most students have been persuaded into believing that Muslims alone invented science. And that the heroes of Muslim science such as Ibn-e-Haytham, Al-Khwarizmi, Omar Khayyam, Ibn-e-Sina, etc owed their scientific discoveries to their strong religious beliefs. This is wrong.

Science is the cumulative effort of humankind with its earliest recorded origins in Babylon and Egypt about 6,000 years ago, thereafter moving to China and India, and then Greece. It was a millennium later that science reached the lands of Islam, where it flourished for 400 years before moving on to Europe. Omar Khayyam, a Muslim, was doubtless a brilliant mathematician. But so was Aryabhatta, a Hindu. What does their faith have to do with their science? Natural geniuses have existed everywhere and at all times.

Today’s massive infusion of religion into the teaching of science dates to the Ziaul Haq days. It was not just school textbooks that were hijacked. In the 1980s, as an applicant to a university teaching position in whichever department, the university’s selection committee would first check your faith.

In those days a favourite question at Quaid-e-Azam University (as probably elsewhere) was to have a candidate recite Dua-i-Qunoot, a rather difficult prayer. Another was to name each of the Holy Prophet’s wives, or be quizzed about the ideology of Pakistan. Deftly posed questions could expose the particularities of the candidate’s sect, personal degree of adherence, and whether he had been infected by liberal ideas.

Most applicants meekly submitted to the grilling. Of these many rose to become today’s chairmen, deans, and vice-chancellors. The bolder ones refused, saying that the questions asked were irrelevant. With strong degrees earned from good overseas universities, they did not have to submit to their bullying inquisitors. Decades later, they are part of a widely dispersed diaspora. Though lost to Pakistan, they have done very well for themselves.

Science has no need for Pakistan; in the rest of the world it roars ahead. But Pakistan needs science because it is the basis of a modern economy and it enables people to gain decent livelihoods. To get there, matters of faith will have to be cleanly separated from matters of science. This is how peoples around the world have managed to keep their beliefs intact and yet prosper. Pakistan can too, but only if it wants.

When Pakistani students open a physics or biology textbook, it is sometimes unclear whether they are actually learning science or, instead, theology. The reason: every science textbook, published by a government-run textbook board in Pakistan, by law must contain in its first chapter how Allah made our world, as well as how Muslims and Pakistanis have created science.

I have no problem with either. But the first properly belongs to Islamic Studies, the second to Islamic or Pakistani history. Neither legitimately belongs to a textbook on a modern-day scientific subject. That’s because religion and science operate very differently and have widely different assumptions. Religion is based on belief and requires the existence of a hereafter, whereas science worries only about the here and now.

Demanding that science and faith be tied together has resulted in national bewilderment and mass intellectual enfeeblement. Millions of Pakistanis have studied science subjects in school and then gone on to study technical, science-based subjects in college and university. And yet most — including science teachers — would flunk if given even the simplest science quiz.

How did this come about? Let’s take a quick browse through a current 10th grade physics book. The introductory section has the customary holy verses. These are followed by a comical overview of the history of physics. Newton and Einstein — the two greatest names — are unmentioned. Instead there’s Ptolemy the Greek, Al-Kindi, Al-Beruni, Ibn-e-Haytham, A.Q. Khan, and — amusingly — the heretical Abdus Salam.

The end-of-chapter exercises test the mettle of students with such questions as: Mark true/false; A) The first revelation sent to the Holy Prophet (PBUH) was about the creation of Heaven? B) The pin-hole camera was invented by Ibn-e-Haytham? C) Al-Beruni declared that Sind was an underwater valley that gradually filled with sand? D) Islam teaches that only men must acquire knowledge?

Dear Reader: You may well gasp in disbelief, or just hold your head in despair. How could Pakistan’s collective intelligence and the quality of what we teach our children have sunk so low? To see more such questions, or to check my translation from Urdu into English, please visit the websitehttp://eacpe.org/ where relevant pages from the above text (as well as from those discussed below) have been scanned and posted.

Take another physics book — this one (English) is for sixth-grade students. It makes abundantly clear its discomfort with the modern understanding of our universe’s beginning. The theory of the Big Bang is attributed to “a priest, George Lamaitre [sic] of Belgium”. The authors cunningly mention his faith hoping to discredit his science. Continuing, they declare that “although the Big Bang Theory is widely accepted, it probably will never be proved”.

While Georges Lemaître was indeed a Catholic priest, he was so much more. A professor of physics, he worked out the expanding universe solution to Einstein’s equations. Lemaître insisted on separating science from religion; he had publicly chided Pope Pius XII when the pontiff grandly declared that Lemaître’s results provided a scientific validation to Catholicism.

Local biology books are even more schizophrenic and confusing than the physics ones. A 10th-grade book starts off its section on ‘Life and its Origins’ unctuously quoting one religious verse after another. None of these verses hint towards evolution, and many Muslims believe that evolution is counter-religious. Then, suddenly, a full page annotated chart hits you in the face. Stolen from some modern biology book written in some other part of the world, it depicts various living organisms evolving into apes and then into modern humans. Ouch!

Such incoherent babble confuses the nature of science — its history, purpose, method, and fundamental content. If the authors are confused, just imagine the impact on students who must learn this stuff. What weird ideas must inhabit their minds!

Compounding scientific ignorance is prejudice. Most students have been persuaded into believing that Muslims alone invented science. And that the heroes of Muslim science such as Ibn-e-Haytham, Al-Khwarizmi, Omar Khayyam, Ibn-e-Sina, etc owed their scientific discoveries to their strong religious beliefs. This is wrong.

Science is the cumulative effort of humankind with its earliest recorded origins in Babylon and Egypt about 6,000 years ago, thereafter moving to China and India, and then Greece. It was a millennium later that science reached the lands of Islam, where it flourished for 400 years before moving on to Europe. Omar Khayyam, a Muslim, was doubtless a brilliant mathematician. But so was Aryabhatta, a Hindu. What does their faith have to do with their science? Natural geniuses have existed everywhere and at all times.

Today’s massive infusion of religion into the teaching of science dates to the Ziaul Haq days. It was not just school textbooks that were hijacked. In the 1980s, as an applicant to a university teaching position in whichever department, the university’s selection committee would first check your faith.

In those days a favourite question at Quaid-e-Azam University (as probably elsewhere) was to have a candidate recite Dua-i-Qunoot, a rather difficult prayer. Another was to name each of the Holy Prophet’s wives, or be quizzed about the ideology of Pakistan. Deftly posed questions could expose the particularities of the candidate’s sect, personal degree of adherence, and whether he had been infected by liberal ideas.

Most applicants meekly submitted to the grilling. Of these many rose to become today’s chairmen, deans, and vice-chancellors. The bolder ones refused, saying that the questions asked were irrelevant. With strong degrees earned from good overseas universities, they did not have to submit to their bullying inquisitors. Decades later, they are part of a widely dispersed diaspora. Though lost to Pakistan, they have done very well for themselves.

Science has no need for Pakistan; in the rest of the world it roars ahead. But Pakistan needs science because it is the basis of a modern economy and it enables people to gain decent livelihoods. To get there, matters of faith will have to be cleanly separated from matters of science. This is how peoples around the world have managed to keep their beliefs intact and yet prosper. Pakistan can too, but only if it wants.

Friday, 6 May 2016

The lies binding Hillsborough to the battle of Orgreave

Ken Capstick in The Guardian

Police covered up their attacks on striking miners. And they used the same tactics after the football tragedy.

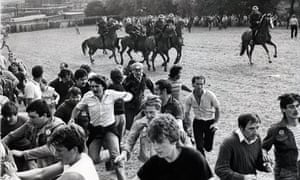

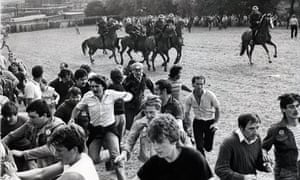

‘For those of us who were there when the ranks of police suddenly opened up and launched a cavalry charge, it felt like civil war.’ Photograph: Photofusion/Rex

Just eight miles separates the patch of ground on the outskirts of Sheffield where Orgreave coking plant once stood from Hillsborough stadium, where 96 people were unlawfully killed on 15 April 1989. To those of us involved in the miners’ strike in south Yorkshire in the 1980s, the so-called “battle of Orgreave” and Britain’s worst football disaster have always been linked.

It was a glorious summer’s day on 18 June 1984. With my son and other mineworkers, I set off for Orgreave to take part in a mass demonstration to try to stop coke being moved from the plant to the steelworks at Scunthorpe.

The miners were in a jovial mood, dressed in T-shirts and plimsolls. To save on petrol most of us travelled four or five to a car. We had been on strike for more than three months, had very little money and relied on the £2 picketing money from the union to pay for petrol. Our destination was to be the scene of one of the bloodiest battle grounds in Britain’s industrial history.

We went to Orgreave to fight to save our industry from what has since been revealed, following the release of cabinet papers in January 2014, as a government plan to kill off the coal mining industry, close 75 pits at a cost of approximately 75,000 jobs, and destroy the National Union of Mineworkers.

The battle of Orgreave was a one-sided contest, as miners suddenly found themselves facing not a police force, but a paramilitary force dressed in riot gear, wielding long truncheons, with strategically placed officers with dogs, and a cavalry charge reminiscent of a medieval battleground.

For those of us who were there when the ranks of police suddenly opened up and launched the charge on horseback, it felt like civil war. Miners had no defence other than to try and outrun the horses. Furthermore, we had to run uphill. Many miners were caught and battered to the ground with truncheons, then outnumbered by police on foot before being roughly handled as they were arrested. Those of us who made it to the top of the hill found refuge in a supermarket or in the nearby mining village.

‘Following the battle, 95 miners were charged with riot, an offence which can carry a life sentence.’ Photograph: Mike Forster/Associated News/Rex

No one died at Orgreave, but it was clearly the intention of the police to create what felt like a life-threatening situation. The police faced no threat from the miners at Orgreave that warranted such a violent response, but it was obvious to those present that the police knew they could act with impunity.

Following the battle, 95 miners were charged with riot, an offence which could carry a life sentence. Gareth Peirce, one of the defending solicitors in the abortive trial that followed, wrote in the Guardian in 1985: “Orgreave … revealed that in this country we now have a standing army available to be deployed against gatherings of civilians whose congregation is disliked by senior police officers. It is answerable to no one; it is trained in tactics which have been released to no one, but which include the deliberate maiming and injuring of innocent persons to disperse them, in complete violation of the law.”

Miners' strike: IPCC considers unredacted Orgreave report

I wasn’t in court when the prosecution of the Orgreave miners was thrown out because the evidence did not stack up. But the trial revealed the way police would collaborate and coordinate evidence in order to get convictions or cover up the truth. In this sense, Orgreave can be seen as a dry run for what happened after the Hillsborough disaster in 1989. Had the South Yorkshire force not been allowed to get away with what they did at Orgreave, perhaps Hillsborough would never have happened.

As the Hillsborough inquest verdicts have shown, we cannot have an unaccountable police force charged with upholding the rule of law but immune to it. We need to know which politicians or officials gave such immunity to the police, if it was given.

Only a full public inquiry into Orgreave will get at the truth, an inquiry to which all documents must be revealed in unredacted form. This inquiry would not just be in the interests of the miners injured on that day, and in the interests of their families. It would be in all our interests, because we all need to understand how a police force came to believe it was a law unto itself. If we don’t, we risk creating the conditions in which another Hillsborough or Orgreave could happen.

In 1985 the miners shouted from the rooftops, but we weren’t heard. Ignored by the media, many gave up. What happened at Orgreave was not a human tragedy on the same scale as Hillsborough. But now, thanks to the tremendous campaign by the Hillsborough families who lost loved ones, and who refused to give up their fight for justice, we have the chance to discover the truth about what happened at Orgreave too.

Police covered up their attacks on striking miners. And they used the same tactics after the football tragedy.

‘For those of us who were there when the ranks of police suddenly opened up and launched a cavalry charge, it felt like civil war.’ Photograph: Photofusion/Rex

Just eight miles separates the patch of ground on the outskirts of Sheffield where Orgreave coking plant once stood from Hillsborough stadium, where 96 people were unlawfully killed on 15 April 1989. To those of us involved in the miners’ strike in south Yorkshire in the 1980s, the so-called “battle of Orgreave” and Britain’s worst football disaster have always been linked.

It was a glorious summer’s day on 18 June 1984. With my son and other mineworkers, I set off for Orgreave to take part in a mass demonstration to try to stop coke being moved from the plant to the steelworks at Scunthorpe.

The miners were in a jovial mood, dressed in T-shirts and plimsolls. To save on petrol most of us travelled four or five to a car. We had been on strike for more than three months, had very little money and relied on the £2 picketing money from the union to pay for petrol. Our destination was to be the scene of one of the bloodiest battle grounds in Britain’s industrial history.

We went to Orgreave to fight to save our industry from what has since been revealed, following the release of cabinet papers in January 2014, as a government plan to kill off the coal mining industry, close 75 pits at a cost of approximately 75,000 jobs, and destroy the National Union of Mineworkers.

The battle of Orgreave was a one-sided contest, as miners suddenly found themselves facing not a police force, but a paramilitary force dressed in riot gear, wielding long truncheons, with strategically placed officers with dogs, and a cavalry charge reminiscent of a medieval battleground.

For those of us who were there when the ranks of police suddenly opened up and launched the charge on horseback, it felt like civil war. Miners had no defence other than to try and outrun the horses. Furthermore, we had to run uphill. Many miners were caught and battered to the ground with truncheons, then outnumbered by police on foot before being roughly handled as they were arrested. Those of us who made it to the top of the hill found refuge in a supermarket or in the nearby mining village.

‘Following the battle, 95 miners were charged with riot, an offence which can carry a life sentence.’ Photograph: Mike Forster/Associated News/Rex

No one died at Orgreave, but it was clearly the intention of the police to create what felt like a life-threatening situation. The police faced no threat from the miners at Orgreave that warranted such a violent response, but it was obvious to those present that the police knew they could act with impunity.

Following the battle, 95 miners were charged with riot, an offence which could carry a life sentence. Gareth Peirce, one of the defending solicitors in the abortive trial that followed, wrote in the Guardian in 1985: “Orgreave … revealed that in this country we now have a standing army available to be deployed against gatherings of civilians whose congregation is disliked by senior police officers. It is answerable to no one; it is trained in tactics which have been released to no one, but which include the deliberate maiming and injuring of innocent persons to disperse them, in complete violation of the law.”

Miners' strike: IPCC considers unredacted Orgreave report

I wasn’t in court when the prosecution of the Orgreave miners was thrown out because the evidence did not stack up. But the trial revealed the way police would collaborate and coordinate evidence in order to get convictions or cover up the truth. In this sense, Orgreave can be seen as a dry run for what happened after the Hillsborough disaster in 1989. Had the South Yorkshire force not been allowed to get away with what they did at Orgreave, perhaps Hillsborough would never have happened.

As the Hillsborough inquest verdicts have shown, we cannot have an unaccountable police force charged with upholding the rule of law but immune to it. We need to know which politicians or officials gave such immunity to the police, if it was given.

Only a full public inquiry into Orgreave will get at the truth, an inquiry to which all documents must be revealed in unredacted form. This inquiry would not just be in the interests of the miners injured on that day, and in the interests of their families. It would be in all our interests, because we all need to understand how a police force came to believe it was a law unto itself. If we don’t, we risk creating the conditions in which another Hillsborough or Orgreave could happen.

In 1985 the miners shouted from the rooftops, but we weren’t heard. Ignored by the media, many gave up. What happened at Orgreave was not a human tragedy on the same scale as Hillsborough. But now, thanks to the tremendous campaign by the Hillsborough families who lost loved ones, and who refused to give up their fight for justice, we have the chance to discover the truth about what happened at Orgreave too.

Thursday, 5 May 2016

Medical Council of India similar to BCCI?

The Hindu

The Supreme Court has given the Centre a deserved rebuke by using its extraordinary powers and setting up a three-member committee headed by former Chief Justice of India R.M. Lodha to perform the statutory functions of the Medical Council of India. The government now has a year to restructure the MCI, the regulatory body for medical education and professional practice. The Centre’s approach to reforming the corruption-afflicted MCI has been wholly untenable; the Dr. Ranjit Roy Chaudhury expert committee that it set up and the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare in the Rajya Sabha had both recommended structural change through amendments to the Indian Medical Council Act. Now that the Lodha panel will steer the MCI, there is hope that key questions swept under the carpet at the council will be addressed quickly. Among the most important is the need to reduce the cost of medical education and increase access in different parts of the country. This must be done to improve the doctor-to-population ratio, which is one for every 1,674 persons, as per the parliamentary panel report, against the WHO-recommended one to 1,000. In fact, it may be even less functionally because not all registered professionals practice medicine. In reality, only people in bigger cities and towns have reasonable access to doctors and hospitals. Removing bottlenecks to starting colleges, such as conditions stipulating the possession of a vast extent of land and needlessly extensive infrastructure, will considerably rectify the imbalance, especially in under-served States. The primary criterion to set up a college should only be the availability of suitable facilities to impart quality medical education.

The development of health facilities has long been affected by a sharp asymmetry between undergraduate and postgraduate seats in medicine. There are only about 25,000 PG seats, against a capacity of 55,000 graduate seats. The Lodha committee is in a position to review this gap, and it can help the Centre expand the system, especially through not-for-profit initiatives. There is also the contentious issue of choosing a common entrance examination. Although the Supreme Court has allowed the National Eligibility-cum-Entrance Test, some States are raising genuine concerns about equity and access. A reform agenda for the MCI must include an admission procedure that eliminates multiplicity of entrance examinations and addresses issues such as the urban-rural divide and language barriers. The Centre’s lack of preparedness in this matter, even after it was deliberated by the parliamentary panel, is all too glaring. The single most important issue that the Lodha committee would have to address is corruption in medical education, in which the MCI is mired. Appointing prominent persons from various fields to a restructured council would shine the light of transparency, and save it from reverting to its image as an “exclusive club” of socially disconnected doctors.

The Supreme Court has given the Centre a deserved rebuke by using its extraordinary powers and setting up a three-member committee headed by former Chief Justice of India R.M. Lodha to perform the statutory functions of the Medical Council of India. The government now has a year to restructure the MCI, the regulatory body for medical education and professional practice. The Centre’s approach to reforming the corruption-afflicted MCI has been wholly untenable; the Dr. Ranjit Roy Chaudhury expert committee that it set up and the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare in the Rajya Sabha had both recommended structural change through amendments to the Indian Medical Council Act. Now that the Lodha panel will steer the MCI, there is hope that key questions swept under the carpet at the council will be addressed quickly. Among the most important is the need to reduce the cost of medical education and increase access in different parts of the country. This must be done to improve the doctor-to-population ratio, which is one for every 1,674 persons, as per the parliamentary panel report, against the WHO-recommended one to 1,000. In fact, it may be even less functionally because not all registered professionals practice medicine. In reality, only people in bigger cities and towns have reasonable access to doctors and hospitals. Removing bottlenecks to starting colleges, such as conditions stipulating the possession of a vast extent of land and needlessly extensive infrastructure, will considerably rectify the imbalance, especially in under-served States. The primary criterion to set up a college should only be the availability of suitable facilities to impart quality medical education.

The development of health facilities has long been affected by a sharp asymmetry between undergraduate and postgraduate seats in medicine. There are only about 25,000 PG seats, against a capacity of 55,000 graduate seats. The Lodha committee is in a position to review this gap, and it can help the Centre expand the system, especially through not-for-profit initiatives. There is also the contentious issue of choosing a common entrance examination. Although the Supreme Court has allowed the National Eligibility-cum-Entrance Test, some States are raising genuine concerns about equity and access. A reform agenda for the MCI must include an admission procedure that eliminates multiplicity of entrance examinations and addresses issues such as the urban-rural divide and language barriers. The Centre’s lack of preparedness in this matter, even after it was deliberated by the parliamentary panel, is all too glaring. The single most important issue that the Lodha committee would have to address is corruption in medical education, in which the MCI is mired. Appointing prominent persons from various fields to a restructured council would shine the light of transparency, and save it from reverting to its image as an “exclusive club” of socially disconnected doctors.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)