“Blessed is the nation that doesn’t need heroes" Goethe. “Hero-worship is strongest where there is least regard for human freedom.” Herbert Spencer

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label war. Show all posts

Showing posts with label war. Show all posts

Thursday 14 April 2022

Tuesday 12 April 2022

A requiem for fine journalism

Jawed Naqvi in The Dawn

RONALD L. Haeberle was a combat photographer with the US army whose pictures exposed the horrors of the My Lai massacre in Vietnam in 1969. Military analyst Daniel Ellsberg, at peril to his life, leaked the papers revealing the cover-up of US perfidies in Vietnam. Mordechai Vanunu was an Israeli scientist who shared his country’s nuclear secrets with a British newspaper. Israel kidnapped him and put him in jail. US soldier Chelsea Manning handed over 750,000 secret military documents to WikiLeaks and was court martialled for it. She went to prison.

There’s no end to ill-informed media chatter about Vladimir Putin’s KGB past. But it took KGB master spy Vasili Mitrokhin to hand over a treasure trove of Kremlin’s secrets to the Western media. Likewise with Edward Snowden, living in exile in Moscow after exposing the US government’s illegal surveillance of its own citizens.

If there were no journalists, it seems, the truth would somehow still come out. That is one’s best bet for Ukraine. Somebody will blow the whistle, almost inevitably, after pattern, as it were, and the world would know a little more than what the media wants us not to know.

It’s a strange war out there in which columns upon columns of enemy tanks were lined up for days without stirring from their highly visible location a short distance from the capital city, and no one took a pot shot at the sitting ducks. Is there something one is missing? It’s a strange war in which the besieged capital of the invaded country should be running low on critical daily resources but its citizens are able to keep their mobile phones charged and these work very efficiently.

An Israeli analyst says the Russians are allowing the phones to work to be able to listen in. It’s tempting to believe that. But then, why couldn’t the Israeli wizard advise his friends in New Delhi to keep the mobile phones running in besieged Kashmir. Not for days or weeks, but for months, till the courts intervened, did Kashmir have no internet. It’s nice to have an Israeli expert talk about phone tapping.

It’s a strange war also, in which leaders and politicians from friendly countries wade into the heart of supposedly besieged cities to cheer on the fighters they are arming to the teeth and return home unscathed. In football matches, the team managers shout out orders from outside the arena. Here you have them walking to the goalkeeper to plan which way to dive to stop the curving ball.

The Ukraine war looks set to reset the world order. It has in the bargain already exposed the overstated claim of objective journalism the West had credited itself with. The claim lay in tatters, of course, for the most part since the US invasion of Iraq. Many in the media covering Ukraine had purveyed brazen lies that provided the fig leaf for the destruction of a robustly secular country like Iraq.

The overwhelming impression being created is that the Russians are being chased out of Ukraine if they are not being drawn into a trap. Frustrated by their failure, the retreating troops are committing war crimes. It would be difficult to regard any army, Western or Eastern, as a saviour of human rights. It could be a great point to start a discussion. Who is going to try whom for the massacres? The US refuses to be a member of the International Criminal Court that is reported to have initiated its probe into the Bucha killings. And neither is Russia looking interested in blessing the court with acceptance. The worried world and the ICC can only persuade but not prosecute a non-member.

The basic question many are keen to ask is this: is the West on top of the situation in Ukraine, or is Russia winning the war, as non-Russian, non-journalist analysts are beginning to assert. Any journalist should be interested in both parts of the question, but asking the latter would be deemed tantamount to betrayal. Or are we heading towards a long-drawn stalemate dipped in even more innocent blood? The even-handed, old-fashioned school of journalism with cautionary words like ‘alleged’ and ‘claimed’ and ‘could not be independently verified’ etc is becoming sadly extinct.

As a South Asian journalist, one grew up admiring the probity and diligence of Western journalists. There was a time when the BBC in all the South Asian languages would be way ahead of domestic news services in credibility and speed. Z.A. Bhutto’s execution and Indira Gandhi’s assassination, for example, were first announced on BBC and only later reported by the national media outfits. Mark Tully and Satish Jacob were household names during the Punjab turmoil. Dalit leader Ram Vilas Paswan told me that he respected Western journalists more because they were honest in describing the injustices of the Hindu caste system. Indian journalists, he said, were mealy-mouthed about caste inequities.

Tully’s dispatches from New Delhi were broadcast in Hindi, Urdu, Bangla, Sinhalese etc. They found audiences in remote villages. One day, Mark Fineman of the Financial Times was travelling with me to a village near Mathura where a Jat girl and two Jatav boys were lynched by a kangaroo court in a typical love story that went tragically wrong. Fineman decided to flash his press card at the village octroi to get past the barrier speedily. The village boys took one look at him and said: “Oh! Mark Tully! You may go.” Incensed, Fineman promptly thrust a five-rupee note into the toll collector’s hand — more than twice the octroi fees and shouted: “No, I’m not Mark Tully. I can never be.”

Likewise, there cannot be another Robert Fisk who died in 2020. However, John Pilger and a few others of the old school are still around to give us a sliver of hope about an otherwise fatally stricken profession.

RONALD L. Haeberle was a combat photographer with the US army whose pictures exposed the horrors of the My Lai massacre in Vietnam in 1969. Military analyst Daniel Ellsberg, at peril to his life, leaked the papers revealing the cover-up of US perfidies in Vietnam. Mordechai Vanunu was an Israeli scientist who shared his country’s nuclear secrets with a British newspaper. Israel kidnapped him and put him in jail. US soldier Chelsea Manning handed over 750,000 secret military documents to WikiLeaks and was court martialled for it. She went to prison.

There’s no end to ill-informed media chatter about Vladimir Putin’s KGB past. But it took KGB master spy Vasili Mitrokhin to hand over a treasure trove of Kremlin’s secrets to the Western media. Likewise with Edward Snowden, living in exile in Moscow after exposing the US government’s illegal surveillance of its own citizens.

If there were no journalists, it seems, the truth would somehow still come out. That is one’s best bet for Ukraine. Somebody will blow the whistle, almost inevitably, after pattern, as it were, and the world would know a little more than what the media wants us not to know.

It’s a strange war out there in which columns upon columns of enemy tanks were lined up for days without stirring from their highly visible location a short distance from the capital city, and no one took a pot shot at the sitting ducks. Is there something one is missing? It’s a strange war in which the besieged capital of the invaded country should be running low on critical daily resources but its citizens are able to keep their mobile phones charged and these work very efficiently.

An Israeli analyst says the Russians are allowing the phones to work to be able to listen in. It’s tempting to believe that. But then, why couldn’t the Israeli wizard advise his friends in New Delhi to keep the mobile phones running in besieged Kashmir. Not for days or weeks, but for months, till the courts intervened, did Kashmir have no internet. It’s nice to have an Israeli expert talk about phone tapping.

It’s a strange war also, in which leaders and politicians from friendly countries wade into the heart of supposedly besieged cities to cheer on the fighters they are arming to the teeth and return home unscathed. In football matches, the team managers shout out orders from outside the arena. Here you have them walking to the goalkeeper to plan which way to dive to stop the curving ball.

The Ukraine war looks set to reset the world order. It has in the bargain already exposed the overstated claim of objective journalism the West had credited itself with. The claim lay in tatters, of course, for the most part since the US invasion of Iraq. Many in the media covering Ukraine had purveyed brazen lies that provided the fig leaf for the destruction of a robustly secular country like Iraq.

The overwhelming impression being created is that the Russians are being chased out of Ukraine if they are not being drawn into a trap. Frustrated by their failure, the retreating troops are committing war crimes. It would be difficult to regard any army, Western or Eastern, as a saviour of human rights. It could be a great point to start a discussion. Who is going to try whom for the massacres? The US refuses to be a member of the International Criminal Court that is reported to have initiated its probe into the Bucha killings. And neither is Russia looking interested in blessing the court with acceptance. The worried world and the ICC can only persuade but not prosecute a non-member.

The basic question many are keen to ask is this: is the West on top of the situation in Ukraine, or is Russia winning the war, as non-Russian, non-journalist analysts are beginning to assert. Any journalist should be interested in both parts of the question, but asking the latter would be deemed tantamount to betrayal. Or are we heading towards a long-drawn stalemate dipped in even more innocent blood? The even-handed, old-fashioned school of journalism with cautionary words like ‘alleged’ and ‘claimed’ and ‘could not be independently verified’ etc is becoming sadly extinct.

As a South Asian journalist, one grew up admiring the probity and diligence of Western journalists. There was a time when the BBC in all the South Asian languages would be way ahead of domestic news services in credibility and speed. Z.A. Bhutto’s execution and Indira Gandhi’s assassination, for example, were first announced on BBC and only later reported by the national media outfits. Mark Tully and Satish Jacob were household names during the Punjab turmoil. Dalit leader Ram Vilas Paswan told me that he respected Western journalists more because they were honest in describing the injustices of the Hindu caste system. Indian journalists, he said, were mealy-mouthed about caste inequities.

Tully’s dispatches from New Delhi were broadcast in Hindi, Urdu, Bangla, Sinhalese etc. They found audiences in remote villages. One day, Mark Fineman of the Financial Times was travelling with me to a village near Mathura where a Jat girl and two Jatav boys were lynched by a kangaroo court in a typical love story that went tragically wrong. Fineman decided to flash his press card at the village octroi to get past the barrier speedily. The village boys took one look at him and said: “Oh! Mark Tully! You may go.” Incensed, Fineman promptly thrust a five-rupee note into the toll collector’s hand — more than twice the octroi fees and shouted: “No, I’m not Mark Tully. I can never be.”

Likewise, there cannot be another Robert Fisk who died in 2020. However, John Pilger and a few others of the old school are still around to give us a sliver of hope about an otherwise fatally stricken profession.

Wednesday 6 April 2022

A women led war on Russia: The weaponisation of finance

Valentina Pop, Sam Fleming and James Politi in The FT

It was the third day of the war in Ukraine, and on the 13th floor of the European Commission’s headquarters Ursula von der Leyen had hit an obstacle.

It was the third day of the war in Ukraine, and on the 13th floor of the European Commission’s headquarters Ursula von der Leyen had hit an obstacle.

The commission president had spent the entire Saturday working the phones in her office in Brussels, seeking consensus among western governments for the most far-reaching and punishing set of financial and economic sanctions ever levelled at an adversary.

With Russia seemingly intent on a rapid occupation of Ukraine, emotions were running high. During a video call with EU leaders on February 24, the day the invasion began, Volodymyr Zelensky, the Ukrainian president, warned: “I might not see you again because I’m next on the list.”

A deal was close but, in Washington, Treasury secretary Janet Yellen was still reviewing the details of the most dramatic and market-sensitive measure — sanctioning the Russian central bank itself. The US had been the driving force behind the sanctions push but, as Yellen pored over the fine print, the Europeans were anxious to push the plans over the finishing line.

Von der Leyen called Mario Draghi, Italian prime minister, and asked him to thrash the details out directly with Yellen. “We were all waiting around, asking, ‘What’s taking so long?’” recalls an EU official. “Then the answer came: Draghi has to work his magic on Yellen.”

Yellen, who used to chair the US Federal Reserve, and Draghi, a former head of the European Central Bank, are veterans of a series of dramatic crises — from the 2008-09 financial collapse to the euro crisis. All the while, they have exuded calm and stability to nervous financial markets.

But in this case, the plan agreed by Yellen and Draghi to freeze a large part of Moscow’s $643bn of foreign currency reserves was something very different: they were effectively declaring financial war on Russia.

The stated intention of the sanctions is to significantly damage the Russian economy. Or as one senior US official put it later that Saturday night after the measures were announced, the sanctions would push the Russian currency “into freefall”.

This is a very new kind of war — the weaponisation of the US dollar and other western currencies to punish their adversaries.

It is an approach to conflict two decades in the making. As voters in the US have tired of military interventions and the so-called “endless wars”, financial warfare has partly filled the gap. In the absence of an obvious military or diplomatic option, sanctions — and increasingly financial sanctions — have become the national security policy of choice.

“This is full-on shock and awe,” says Juan Zarate, a former senior White House official who helped devise the financial sanctions America has developed over the past 20 years. “It’s about as aggressive an unplugging of the Russian financial and commercial system as you can imagine.”

The weaponisation of finance has profound implications for the future of international politics and economics. Many of the basic assumptions about the post cold war era are being turned on their head. Globalisation was once sold as a barrier to conflict, a web of dependencies that would bring former foes ever closer together. Instead, it has become a new battleground.

The potency of financial sanctions derives from the omnipresence of the US dollar. It is the most used currency for trade and financial transactions — with a US bank often involved. America’s capital markets are the deepest in the world, and US Treasury bonds act as a backstop to the global financial system.

As a result, it is very hard for financial institutions, central banks and even many companies to operate if they are cut off from the US dollar and the American financial system. Add in the euro, which is the second most held currency in central bank reserves, as well as sterling, the yen and the Swiss franc, and the impact of such sanctions is even more chilling.

The US has sanctioned central banks before — North Korea, Iran and Venezuela — but they were largely isolated from global commerce. The sanctions on Russia’s central bank are the first time this weapon has been used against a major economy and the first time as part of a war — especially a conflict involving one of the leading nuclear powers.

Of course, there are huge risks in such an approach. The central bank sanctions could prompt a backlash against the dollar’s dominance in global finance. In the five weeks since the measures were first imposed, the Russian rouble has recovered much of the ground it initially lost and officials in Moscow claim they will find ways around the sanctions.

Whatever the result, the moves to freeze Russia’s reserves marks a historic shift in the conduct of foreign policy. “These economic sanctions are a new kind of economic statecraft with the power to inflict damage that rivals military might,” US President Joe Biden said in a speech in Warsaw in late March. The measures were “sapping Russian strength, its ability to replenish its military, and its ability to project power”.

Global financial police

Like so much else in American life, the new era of financial warfare began on 9/11. In the aftermath of the terror attacks, the US invaded Afghanistan, moved on to Iraq to topple Saddam Hussein and used drones to kill alleged terrorists on three continents. But with much less scrutiny and fanfare, it also developed the powers to act as the global financial police.

Within weeks of the attacks on New York and Washington, George W Bush pledged to “starve the terrorists of funding”. The Patriot Act, the controversial law, which provided the basis for the Bush administration’s use of surveillance and indefinite detention, also gave the Treasury department the power to effectively cut off any financial institution involved in money laundering from the US financial system.

By coincidence, the first country to be threatened under this law was Ukraine, which the Treasury warned in 2002 risked having its banks compromised by Russian organised crime. Shortly after, Ukraine passed a new law to prevent money laundering.

Treasury officials also negotiated to gain access to data about suspected terrorists from Swift, the Belgium-based messaging system that is the switchboard for international financial transactions — the first step in an expanded network of intelligence on money moving around the world.

The financial toolkit used to go after al-Qaeda’s money was soon applied to a much bigger target — Iran and its nuclear programme.

Stuart Levey, who had been appointed as the Treasury’s first under-secretary of terrorism and financial intelligence, remembers hearing Bush complain that all the conventional trade sanctions on Iran had already been imposed, leaving the US without leverage. “I pulled my team together and said: ‘We haven’t begun to use these tools, let’s give him something he can use with Iran’,” he says.

The US sought to squeeze Iran’s access to the international financial system. Levey and other officials would visit European banks and quietly inform them about accounts with links to the Iranian regime. European governments hated that an American official was effectively telling their banks how to do business, but no one wanted to fall foul of the US Treasury.

During the Obama administration, when the White House was facing pressure to take military action against its nuclear installations, the US imposed sanctions on Iran’s central bank — the final stage in a campaign to strangle its economy.

Levey argues that financial sanctions not only put pressure on Iran to negotiate the 2015 deal on its nuclear programme but also cleared a path for this year’s action on Russia.

“On Iran, we were using machetes to cut down the path step by step, but now people are able to go down it very quickly,” he says. “Going after the central bank of a country like Russia is about as powerful a step as you can take in the category of financial sector sanctions.”

Central banks do not just print money and monitor the banking system, they can also provide a vital economic buffer in a crisis — defending a currency or paying for essential imports.

Russia’s reserves increased after its 2014 annexation of Crimea as it sought insurance against future US sanctions — earning the term “Fortress Russia”. China’s large holdings of US Treasury bonds were once seen as a potential source of geopolitical leverage. “How do you deal toughly with your banker?” then secretary of state Hillary Clinton asked in 2009.

But the western sanctions on Russia’s central bank have undercut its ability to support the economy. According to Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum, a central bank research and advisory group, around two-thirds of Russia’s reserves are likely to have been neutralised.

“The action against the central bank is rather like if you have savings to be used in case of emergency and when the emergency arrives the bank says you can’t take them out,” says a senior European economic policy official.

A revived transatlantic alliance

There is an irony behind a joint package of American and EU financial sanctions: European leaders have spent much of the past five decades criticising the outsized influence of the US currency.

One of the striking features of the war in Ukraine is the way Europe has worked so closely with the US. Sanctions planning began in November when western intelligence picked up strong evidence that Vladimir Putin’s forces were building up along the Ukrainian border.

Biden asked Yellen to draw up plans for what measures could be taken to respond to an invasion. From that moment the US began coordinating with the EU, UK and others. A senior state department official says that between then and the February 24 invasion, top Biden administration officials spent “an average of 10 to 15 hours a week on secure calls or video conferences with the EU and member states” to co-ordinate the sanctions.

In Washington, the sanctions plans were led by Daleep Singh, a former New York Fed official now deputy national security adviser for international economics at the White House, and Wally Adeyemo, a former BlackRock executive serving as deputy Treasury secretary. Both had worked in the Obama administration when the US and Europe had disagreed about how to respond to Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

The EU was also desperate to avoid a more recent embarrassing precedent regarding Belarus sanctions, which ended up much weaker as countries sought carve-outs for their industries. So in a departure from previous practices, the EU effort was co-ordinated directly from von der Leyen’s office through Bjoern Seibert, her chief of staff.

“Seibert was key, he was the only one having the overview on the EU side and in constant contact with the US on this,” recalls an EU diplomat.

A senior state department official says Germany’s decision to scrap the Nord Stream 2 pipeline after the invasion was crucial in bringing hesitant Europeans along. It was “a very important signal to other Europeans that sacred cows would have to be sacrificed,” says the official.

The other central figure was Canada’s finance minister Chrystia Freeland, who is of Ukrainian descent and has been in close contact with officials in Kyiv. Just a few hours after Russian tanks started rolling into Ukraine, Freeland sent a written proposal to both the US Treasury and the state department with a specific plan to punish the Russian central bank, a western official says. That day, Justin Trudeau, Canada’s prime minister, raised the idea at a G7 leaders emergency summit. And Freeland issued an emotional message to the Ukrainian community in Canada. “Now is the time to remember,” she said, before switching to Ukrainian, “Ukraine is not yet dead.”

The threat of economic pain may not have deterred Putin from invading, but western leaders believe the financial sanctions that have been put in place since the invasion are evidence of a revitalised transatlantic alliance — and a rebuke to the idea that democracies are too slow and hesitant.

“We have never had in the history of the European Union such close contacts with the Americans on a security issue as we have now — it’s really unprecedented,” says one senior EU official.

Draghi takes the initiative

In the end, the move against Russia’s central bank was the product of 72 hours of intensive diplomacy that mixed high emotion and technical detail.

The idea had not been the priority of prewar planning, which focused more on which Russian banks to cut off from Swift. But the ferocity of Russia’s invasion brought the most aggressive sanctions options to the fore.

“The horror of Russia’s unacceptable, unjustified, and unlawful invasion of Ukraine and targeting of civilians — that really unlocked our ability to take further steps,” says one senior state department official.

In Europe, it was Draghi who pushed the idea of sanctioning the central bank at the emergency EU summit on the night of the invasion. Italy, a big importer of Russian gas, had often been hesitant in the past about sanctions. But the Italian leader argued that Russia’s stockpile of reserves could be used to cushion the blow of other sanctions, according to one EU official.

“To counter that . . . you need to freeze the assets,” the official says.

The last-minute nature of discussions was critical to ensure Moscow was caught off-guard: given enough notice, Moscow could have started moving some of its reserves into other currencies. An EU official says that given reports Moscow had started placing orders, the measures needed to be ready by the time the markets opened on Monday so that banks would not process any trades.

“We took the Russians by surprise — they didn’t pick up on it until too late,” the official says.

According to Adeyemo at the US Treasury: “We were in a place where we knew they really couldn’t find another convertible currency that they could use and try to subvert this.”

The last-minute talks caught some western allies off guard — forcing them to scramble to implement the measures in time. In the UK, they triggered a frantic weekend effort by British Treasury officials to finalise details before the markets opened in London at 7am on Monday. Chancellor Rishi Sunak communicated by WhatsApp with officials through the night, with the work only concluding at 4am.

No clear political strategy

Yet if the western response has been defined by unity, there are already signs of potential faultlines — especially given the new claims about war crimes, which have prompted calls for further sanctions.

Western governments have not defined what Russia would need to do for sanctions to be lifted, leaving some of the difficult questions about the political strategy for a later date. Is the objective to inflict short-term pain on Russia to inhibit the war effort or long-term containment?

Even when they work, sanctions take a long time to have an impact. However, the economic pain from the crisis is being unevenly felt, with Europe suffering a much bigger blow than the US.

Europe has so far been reluctant to impose an oil and gas embargo, given the bloc’s high dependence on Russian energy imports. But since the atrocities allegedly perpetrated by Russian soldiers in the suburbs of Kyiv have been revealed, a fresh round of EU sanctions was announced on Tuesday that will include a ban on Russian coal imports and, at a later stage, possibly also oil. A decision among the 27 capitals is expected later this week.

The other key factor is whether the west can win the narrative contest over sanctions — both in Russia and in the rest of the world.

Speaking in 2019, Singh, the White House official, admitted that sanctions imposed on Russia after Crimea were not as effective as hoped because Russian propaganda succeeded in blaming the west for economic problems.

“Our inability to counter Putin’s scapegoating,” he told Congress, “gave the regime far more staying power than it would have enjoyed otherwise.”

In the coming weeks and months, Putin will try to convince a Russian population undergoing economic hardship that it is the victim, not the aggressor.

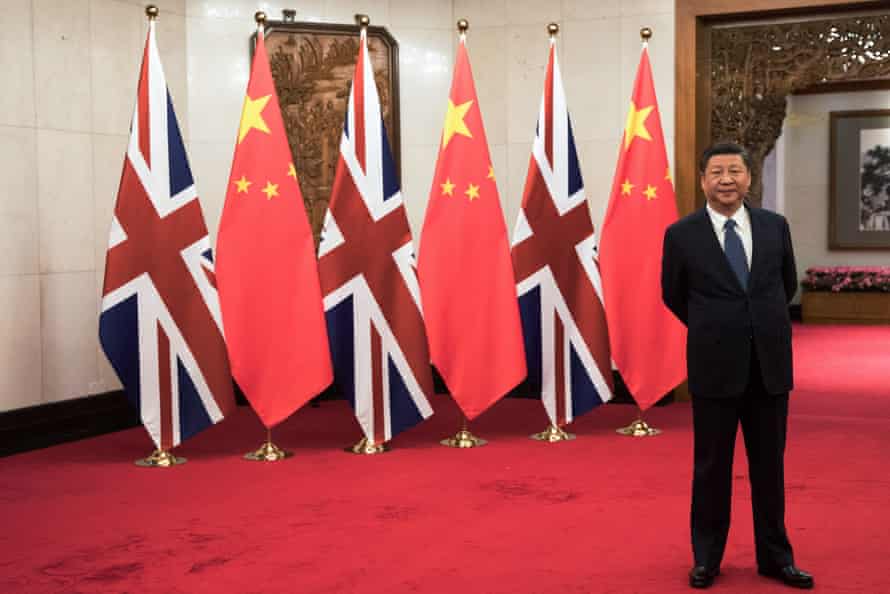

To China, India, Brazil and the other countries which might potentially help him evade the western sanctions, Putin will pose a deeper question about the role of the US dollar in the global economy: can you still trust America?

How do sanctions work?

Saturday 12 March 2022

Sunday 6 March 2022

Friday 25 February 2022

Deception and destruction can still blind the enemy

From The Economist

There are four ways for those who would hide to fight back against those trying to find them: destruction, deafening, disappearance and deception. Technological approaches to all of those options will be used to counter the advantages that bringing more sensors to the battlespace offers. As with the sensors, what those technologies achieve will depend on the tactics used.

Destruction is straightforward: blow up the sensor. Missiles which home in on the emissions from radars are central to establishing air superiority; one of the benefits of stealth, be it that of an f-35 or a Harop drone, lies in getting close enough to do so reliably.

Radar has to reveal itself to work, though. Passive systems can be both trickier to sniff out and cheaper to replace. Theatre-level air-defence systems are not designed to spot small drones carrying high-resolution smartphone cameras, and would be an extraordinarily expensive way of blowing them up.

But the ease with which American drones wandered the skies above Iraq, Afghanistan and other post-9/11 war zones has left a mistaken impression about the survivability of uavs. Most Western armies have not had to worry about things attacking them from the sky since the Korean war ended in 1953. Now that they do, they are investing in short-range air defences. Azerbaijan’s success in Nagorno-Karabakh was in part down to the Armenians not being up to snuff in this regard. Armed forces without many drones—which is still most of them—will find their stocks quickly depleted if used against a seasoned, well-equipped force.

Stocks will surely increase if it becomes possible to field more drones for the same price. And low-tech drones which can be used as flying ieds will make things harder when fighting irregular forces. But anti-drone options should get better too. Stephen Biddle of Columbia University argues that the trends making drones more capable will make anti-drone systems better, too. Such systems actually have an innate advantage, he suggests; they look up into the sky, in which it is hard to hide, while drones look down at the ground, where shelter and camouflage are more easily come by. And small motors cannot lift much by way of armour.

Moving from cheap sensors to the most expensive, satellites are both particularly valuable in terms of surveillance and communication and very vulnerable. America, China, India and Russia, all of which would rely on satellites during a war, have all tested ground-launched anti-satellite missiles in the past two decades; some probably also have the ability to kill one satellite with another. The degree to which they are ready to gouge out each other’s eyes in the sky will be a crucial indicator of escalation should any of those countries start fighting each other. Destroying satellites used to detect missile launches could presage a pre-emptive nuclear strike—and for that very reason could bring one about.

Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the face

Satellites are also vulnerable to sensory overload, as are all sensors. Laser weapons which blind humans are outlawed by international agreement but those that blind cameras are not; nor are microwave beams which fry electronics. America says that Russia tries to dazzle its orbiting surveillance systems with lasers on a regular basis.

The ability to jam, overload or otherwise deafen the other side’s radar and radios is the province of electronic warfare (ew). It is a regular part of military life to probe your adversaries’ ew capabilities when you get a chance. The deployment of American and Russian forces close to each other in northern Syria provided just such an opportunity. “They are testing us every day,” General Raymond Thomas, then head of American special forces, complained in 2018, “knocking our communications down” and going so far as “disabling” America’s own ec-130 electronic-warfare planes.

In Green Dagger, an exercise held in California last October, an American Marine Corps regiment was tasked with seizing a town and two villages defended by an opposing force cobbled together from other American marines, British and Dutch commandos and Emirati special forces. It struggled to do so. When small teams of British commandos attacked the regiment’s rear areas, paralysing its advance, the marines were hard put to target them before they moved, says Jack Watling of the Royal United Services Institute, a think-tank in London. One reason was the commandos’ effective ew attacks on the marines’ command posts.

Just as what sees can be blinded and what hears, deafened, what tries to understand can be confused. Britain’s national cyber-strategy, published in December, explicitly says that one task of the country’s new National Cyber Force, a body staffed by spooks and soldiers, is to “disrupt online and communications systems”. Armies that once manoeuvred under air cover will now need to do so under “cyber-deception cover”, says Ed Stringer, a retired air marshal who led recent reforms in British military thinking. “There’s a point at which the screens of the opposition need to go a bit funny,” says Mr Stringer, “not so much that they immediately spot what you’re doing but enough to distract and confuse.” In time the lines between ew, cyber-offence and psychological operations seem set to blur.

The ability to degrade the other side’s sensors, interrupt its communications and mess with its head does not replace old-fashioned camouflage and newfangled stealth; they remain the bread and butter of a modern military. Tanks are covered in foliage; snipers wear ghillie suits. Warplanes use radiation-absorbent material and angled surfaces so as not to reflect radio waves back to the radar that sent them. Russia has platoons dedicated to spraying the air with aerosols designed to block ultraviolet, infrared and radar waves. During their recent border stand-off, India and China both employed camouflage designed to confuse sensors with a broader spectral range than the human eye.

According to Mr Biddle, over the past 30 years “cover and concealment”, along with other tactics, have routinely allowed forces facing American precision weapons to avoid major casualties. He points to the examples of al-Qaeda at the Battle of Tora Bora in eastern Afghanistan in 2001 and Saddam Hussein’s Republican Guard in 2003, both of whom were overrun in close combat rather than through long-range strikes. Weapons get more lethal, he says, but their targets adapt.

Hiding is made easier by the fact that the seekers’ new capabilities, impressive as they may be, are constrained by the realities of budgets and logistics. Not everything armies want can be afforded; not everything they procure can be put into the field in a timely manner. In real operations, as opposed to PowerPoint presentations, sensor coverage is never unlimited.

“There is no way that we're going to be able to see everything, all of the time, everywhere,” says a British general. “It's just physically impossible. And therefore there will always be something that can happen without us seeing it.” In the Green Dagger exercise the attacking marine regiment lacked thermal-imaging equipment and did not have prompt access to satellite pictures. It was a handicap, but a realistic one. Rounding up commandos was not the regiment’s “main effort”, in military parlance. It might well not have been kitted out for it.

When hiding is hard, it helps to increase the number of things the enemy has to look at. “With modern sensors…it is really, really difficult to avoid being detected,” says Petter Bedoire, the chief technology officer for Saab, a Swedish arms company. “So instead you need to saturate your adversaries’ sensors and their situational awareness.” A system looking at more things will make more mistakes. Stretch it far enough and it could even collapse, as poorly configured servers do when hackers mount “denial of service” attacks designed to overwhelm them with internet traffic.

Dividing your forces is a good way to increase the cognitive load. A lot of small groups are harder to track and target than a few big ones, as the commandos in Green Dagger knew. What is more, if you take shots at one group you reveal some of your shooters to the rest. The less valuable each individual target is, the bigger an issue that becomes.

Decoys up the ante. During the first Gulf war Saddam Hussein unleashed his arsenal of Scud missiles on Bahrain, Israel and Saudi Arabia. The coalition Scud hunters responsible for finding the small (on the scale of a vast desert) mobile missile launchers he was using seemed to have all the technology they might wish for: satellites that could spot the thermal-infrared signature of a rocket launch, aircraft bristling with radar and special forces spread over tens of thousands of square kilometres acting as spotters. Nevertheless an official study published two years later concluded that there was no “indisputable” proof that America had struck any launchers at all “as opposed to high-fidelity decoys”.

One of the advantages data fusion offers seekers is that it demands more of decoys; in surveillance aircraft electronic emissions, radar returns and optical images can now be displayed on a single screen, highlighting any discrepancies between an object’s visual appearance and its electronic signature. But decoy-making has not stood still. Iraq’s fake Scuds looked like the real thing to un observers just 25 metres away; verisimilitude has improved “immensely” since then, particularly in the past decade, says Steen Bisgaard, the founder of GaardTech, an Australian company which builds replica vehicles to serve as both practice targets and decoys.

Mr Bisgaard says he can sell you a very convincing mobile simulacrum of a British Challenger II tank, one with a turret and guns that move, the heat signature of a massive diesel engine and a radio transmitter that works at military wavelengths, all for less than a 20th of the £5m a real tank would set you back. Shipped in a flat pack it can be assembled in an hour or so.

Seeing a tank suddenly appear somewhere, rather than driving there, would be something of a giveaway. But manoeuvre can become part of the mimicry. Rémy Hemez, a French army officer, imagines a future where armies deploy large “robotic decoy formations using ai to move along and create a diversion”. Simulating a build up like the one which Russia has emplaced on Ukraine’s border is still beyond anyone’s capabilities. But decoys and deception—in which Russia’s warriors are well versed—can be used to confuse.

Disappearance and deception often have synergy. Stealth technologies do not need to make an aircraft completely invisible. Just making its radar cross-section small enough that a cheap little decoy can mimic it is a real advantage. The same applies, mutatis mutandis, to submarines. If you build lots of intercontinental-ballistic-missile silos but put icbms into only a few—a tactic China may be exploring—an enemy will have to use hundreds of its missiles to be sure of getting a dozen or so of yours.

Shooting at decoys is not just a waste of material. It also reveals where your shooters are. Silent Impact, a 155mm artillery shell produced by src, an American firm, can transmit electronic signals as if it were a radar or a weapons platform as it flies through the sky and settles to the ground under a parachute. Any enemy who takes the bait reveals the position of their guns.

The advent of ai should offer new ways of telling the real from the fake; but it could also offer new opportunities for deception. The things that make an ai say “Tank!” may be quite different to what humans think of as tankiness, thus unmasking decoys that fool humans. At the same time the ai may ignore features which humans consider blindingly obvious. Benjamin Jensen of American University tells the story of marines training against a high-end sentry camera equipped with object-recognition software. The first marines, who tried to sneak up by crawling low, were quickly detected. Then one of them grabbed a piece of tree bark, placed it in front of his face and walked right up to the camera unmolested. The system saw nothing out of the ordinary about an ambulatory plant.

The problem is that ais, and their masters, learn. In time they will rumble such hacks. Basing a subsequent all-out assault on Birnam Wood tactics would be to risk massacre. “You can always beat the algorithm once by radical improvisation,” says Mr Jensen. “But it's hard to know when that will happen.”

The advantages of staying put

Similar uncertainties will apply more widely. Everyone knows that sensors and autonomous platforms can get cheaper and cheaper, that computing at the edge can reduce strain on the capacity of data systems, and that all this can make kill chains shorter. But the rate of progress—both your progress, and your adversaries’—is hard to gauge. Who has the advantage will often not be known until the forces contest the battlespace.

The unpredictability extends beyond who will win particular fights. It spreads out to the way in which fighting will best be done. Over the past century military thinking has contrasted attrition, which wears down the opponent’s resources in a frontal slugfest, and manoeuvre, which seeks to use fast moving forces to disrupt an enemy’s decision-making, logistics and cohesion. Manoeuvre offers the possibility of victory without the wholesale destruction of the enemies’ forces, and in the West it has come to hold the upper hand, with attrition often seen as a throwback to a more primitive age.

That is a mistake, argues Franz-Stefan Gady of the International Institute for Strategic Studies, a think-tank. Surviving in an increasingly transparent battlespace may well be possible. But it will take effort. Both attackers who want to take ground and defenders who wish to hold it will need to build “complex multiple defensive layers” around their positions, including air defences, electronic countermeasures and sensors of their own. Movement will still be necessary—but it will be dispersed. Consolidated manoeuvres big and sweeping enough to generate “shock and awe” will be slowed down by unwieldy aerial electromagnetic umbrellas and advertise themselves in advance, thereby producing juicy targets.

The message of Azerbaijan’s victory is not that blitzkrieg has been reborn and “the drone will always get through”. It is that preparation and appropriate tactics matter as much as ever, and you need to know what to prepare against. The new technologies of hide and seek will sometimes—if Mr Gady is right, often—favour the defence. A revolution in sensors, data and decision-making built to make targeting easier and kill chains quicker may yet result in a form of warfare that is slower, harder and messier.

There are four ways for those who would hide to fight back against those trying to find them: destruction, deafening, disappearance and deception. Technological approaches to all of those options will be used to counter the advantages that bringing more sensors to the battlespace offers. As with the sensors, what those technologies achieve will depend on the tactics used.

Destruction is straightforward: blow up the sensor. Missiles which home in on the emissions from radars are central to establishing air superiority; one of the benefits of stealth, be it that of an f-35 or a Harop drone, lies in getting close enough to do so reliably.

Radar has to reveal itself to work, though. Passive systems can be both trickier to sniff out and cheaper to replace. Theatre-level air-defence systems are not designed to spot small drones carrying high-resolution smartphone cameras, and would be an extraordinarily expensive way of blowing them up.

But the ease with which American drones wandered the skies above Iraq, Afghanistan and other post-9/11 war zones has left a mistaken impression about the survivability of uavs. Most Western armies have not had to worry about things attacking them from the sky since the Korean war ended in 1953. Now that they do, they are investing in short-range air defences. Azerbaijan’s success in Nagorno-Karabakh was in part down to the Armenians not being up to snuff in this regard. Armed forces without many drones—which is still most of them—will find their stocks quickly depleted if used against a seasoned, well-equipped force.

Stocks will surely increase if it becomes possible to field more drones for the same price. And low-tech drones which can be used as flying ieds will make things harder when fighting irregular forces. But anti-drone options should get better too. Stephen Biddle of Columbia University argues that the trends making drones more capable will make anti-drone systems better, too. Such systems actually have an innate advantage, he suggests; they look up into the sky, in which it is hard to hide, while drones look down at the ground, where shelter and camouflage are more easily come by. And small motors cannot lift much by way of armour.

Moving from cheap sensors to the most expensive, satellites are both particularly valuable in terms of surveillance and communication and very vulnerable. America, China, India and Russia, all of which would rely on satellites during a war, have all tested ground-launched anti-satellite missiles in the past two decades; some probably also have the ability to kill one satellite with another. The degree to which they are ready to gouge out each other’s eyes in the sky will be a crucial indicator of escalation should any of those countries start fighting each other. Destroying satellites used to detect missile launches could presage a pre-emptive nuclear strike—and for that very reason could bring one about.

Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the face

Satellites are also vulnerable to sensory overload, as are all sensors. Laser weapons which blind humans are outlawed by international agreement but those that blind cameras are not; nor are microwave beams which fry electronics. America says that Russia tries to dazzle its orbiting surveillance systems with lasers on a regular basis.

The ability to jam, overload or otherwise deafen the other side’s radar and radios is the province of electronic warfare (ew). It is a regular part of military life to probe your adversaries’ ew capabilities when you get a chance. The deployment of American and Russian forces close to each other in northern Syria provided just such an opportunity. “They are testing us every day,” General Raymond Thomas, then head of American special forces, complained in 2018, “knocking our communications down” and going so far as “disabling” America’s own ec-130 electronic-warfare planes.

In Green Dagger, an exercise held in California last October, an American Marine Corps regiment was tasked with seizing a town and two villages defended by an opposing force cobbled together from other American marines, British and Dutch commandos and Emirati special forces. It struggled to do so. When small teams of British commandos attacked the regiment’s rear areas, paralysing its advance, the marines were hard put to target them before they moved, says Jack Watling of the Royal United Services Institute, a think-tank in London. One reason was the commandos’ effective ew attacks on the marines’ command posts.

Just as what sees can be blinded and what hears, deafened, what tries to understand can be confused. Britain’s national cyber-strategy, published in December, explicitly says that one task of the country’s new National Cyber Force, a body staffed by spooks and soldiers, is to “disrupt online and communications systems”. Armies that once manoeuvred under air cover will now need to do so under “cyber-deception cover”, says Ed Stringer, a retired air marshal who led recent reforms in British military thinking. “There’s a point at which the screens of the opposition need to go a bit funny,” says Mr Stringer, “not so much that they immediately spot what you’re doing but enough to distract and confuse.” In time the lines between ew, cyber-offence and psychological operations seem set to blur.

The ability to degrade the other side’s sensors, interrupt its communications and mess with its head does not replace old-fashioned camouflage and newfangled stealth; they remain the bread and butter of a modern military. Tanks are covered in foliage; snipers wear ghillie suits. Warplanes use radiation-absorbent material and angled surfaces so as not to reflect radio waves back to the radar that sent them. Russia has platoons dedicated to spraying the air with aerosols designed to block ultraviolet, infrared and radar waves. During their recent border stand-off, India and China both employed camouflage designed to confuse sensors with a broader spectral range than the human eye.

According to Mr Biddle, over the past 30 years “cover and concealment”, along with other tactics, have routinely allowed forces facing American precision weapons to avoid major casualties. He points to the examples of al-Qaeda at the Battle of Tora Bora in eastern Afghanistan in 2001 and Saddam Hussein’s Republican Guard in 2003, both of whom were overrun in close combat rather than through long-range strikes. Weapons get more lethal, he says, but their targets adapt.

Hiding is made easier by the fact that the seekers’ new capabilities, impressive as they may be, are constrained by the realities of budgets and logistics. Not everything armies want can be afforded; not everything they procure can be put into the field in a timely manner. In real operations, as opposed to PowerPoint presentations, sensor coverage is never unlimited.

“There is no way that we're going to be able to see everything, all of the time, everywhere,” says a British general. “It's just physically impossible. And therefore there will always be something that can happen without us seeing it.” In the Green Dagger exercise the attacking marine regiment lacked thermal-imaging equipment and did not have prompt access to satellite pictures. It was a handicap, but a realistic one. Rounding up commandos was not the regiment’s “main effort”, in military parlance. It might well not have been kitted out for it.

When hiding is hard, it helps to increase the number of things the enemy has to look at. “With modern sensors…it is really, really difficult to avoid being detected,” says Petter Bedoire, the chief technology officer for Saab, a Swedish arms company. “So instead you need to saturate your adversaries’ sensors and their situational awareness.” A system looking at more things will make more mistakes. Stretch it far enough and it could even collapse, as poorly configured servers do when hackers mount “denial of service” attacks designed to overwhelm them with internet traffic.

Dividing your forces is a good way to increase the cognitive load. A lot of small groups are harder to track and target than a few big ones, as the commandos in Green Dagger knew. What is more, if you take shots at one group you reveal some of your shooters to the rest. The less valuable each individual target is, the bigger an issue that becomes.

Decoys up the ante. During the first Gulf war Saddam Hussein unleashed his arsenal of Scud missiles on Bahrain, Israel and Saudi Arabia. The coalition Scud hunters responsible for finding the small (on the scale of a vast desert) mobile missile launchers he was using seemed to have all the technology they might wish for: satellites that could spot the thermal-infrared signature of a rocket launch, aircraft bristling with radar and special forces spread over tens of thousands of square kilometres acting as spotters. Nevertheless an official study published two years later concluded that there was no “indisputable” proof that America had struck any launchers at all “as opposed to high-fidelity decoys”.

One of the advantages data fusion offers seekers is that it demands more of decoys; in surveillance aircraft electronic emissions, radar returns and optical images can now be displayed on a single screen, highlighting any discrepancies between an object’s visual appearance and its electronic signature. But decoy-making has not stood still. Iraq’s fake Scuds looked like the real thing to un observers just 25 metres away; verisimilitude has improved “immensely” since then, particularly in the past decade, says Steen Bisgaard, the founder of GaardTech, an Australian company which builds replica vehicles to serve as both practice targets and decoys.

Mr Bisgaard says he can sell you a very convincing mobile simulacrum of a British Challenger II tank, one with a turret and guns that move, the heat signature of a massive diesel engine and a radio transmitter that works at military wavelengths, all for less than a 20th of the £5m a real tank would set you back. Shipped in a flat pack it can be assembled in an hour or so.

Seeing a tank suddenly appear somewhere, rather than driving there, would be something of a giveaway. But manoeuvre can become part of the mimicry. Rémy Hemez, a French army officer, imagines a future where armies deploy large “robotic decoy formations using ai to move along and create a diversion”. Simulating a build up like the one which Russia has emplaced on Ukraine’s border is still beyond anyone’s capabilities. But decoys and deception—in which Russia’s warriors are well versed—can be used to confuse.

Disappearance and deception often have synergy. Stealth technologies do not need to make an aircraft completely invisible. Just making its radar cross-section small enough that a cheap little decoy can mimic it is a real advantage. The same applies, mutatis mutandis, to submarines. If you build lots of intercontinental-ballistic-missile silos but put icbms into only a few—a tactic China may be exploring—an enemy will have to use hundreds of its missiles to be sure of getting a dozen or so of yours.

Shooting at decoys is not just a waste of material. It also reveals where your shooters are. Silent Impact, a 155mm artillery shell produced by src, an American firm, can transmit electronic signals as if it were a radar or a weapons platform as it flies through the sky and settles to the ground under a parachute. Any enemy who takes the bait reveals the position of their guns.

The advent of ai should offer new ways of telling the real from the fake; but it could also offer new opportunities for deception. The things that make an ai say “Tank!” may be quite different to what humans think of as tankiness, thus unmasking decoys that fool humans. At the same time the ai may ignore features which humans consider blindingly obvious. Benjamin Jensen of American University tells the story of marines training against a high-end sentry camera equipped with object-recognition software. The first marines, who tried to sneak up by crawling low, were quickly detected. Then one of them grabbed a piece of tree bark, placed it in front of his face and walked right up to the camera unmolested. The system saw nothing out of the ordinary about an ambulatory plant.

The problem is that ais, and their masters, learn. In time they will rumble such hacks. Basing a subsequent all-out assault on Birnam Wood tactics would be to risk massacre. “You can always beat the algorithm once by radical improvisation,” says Mr Jensen. “But it's hard to know when that will happen.”

The advantages of staying put

Similar uncertainties will apply more widely. Everyone knows that sensors and autonomous platforms can get cheaper and cheaper, that computing at the edge can reduce strain on the capacity of data systems, and that all this can make kill chains shorter. But the rate of progress—both your progress, and your adversaries’—is hard to gauge. Who has the advantage will often not be known until the forces contest the battlespace.

The unpredictability extends beyond who will win particular fights. It spreads out to the way in which fighting will best be done. Over the past century military thinking has contrasted attrition, which wears down the opponent’s resources in a frontal slugfest, and manoeuvre, which seeks to use fast moving forces to disrupt an enemy’s decision-making, logistics and cohesion. Manoeuvre offers the possibility of victory without the wholesale destruction of the enemies’ forces, and in the West it has come to hold the upper hand, with attrition often seen as a throwback to a more primitive age.

That is a mistake, argues Franz-Stefan Gady of the International Institute for Strategic Studies, a think-tank. Surviving in an increasingly transparent battlespace may well be possible. But it will take effort. Both attackers who want to take ground and defenders who wish to hold it will need to build “complex multiple defensive layers” around their positions, including air defences, electronic countermeasures and sensors of their own. Movement will still be necessary—but it will be dispersed. Consolidated manoeuvres big and sweeping enough to generate “shock and awe” will be slowed down by unwieldy aerial electromagnetic umbrellas and advertise themselves in advance, thereby producing juicy targets.

The message of Azerbaijan’s victory is not that blitzkrieg has been reborn and “the drone will always get through”. It is that preparation and appropriate tactics matter as much as ever, and you need to know what to prepare against. The new technologies of hide and seek will sometimes—if Mr Gady is right, often—favour the defence. A revolution in sensors, data and decision-making built to make targeting easier and kill chains quicker may yet result in a form of warfare that is slower, harder and messier.

Monday 24 January 2022

Wednesday 25 August 2021

Who’s to blame for the Afghanistan chaos? Remember the war’s cheerleaders

Today the media are looking for scapegoats, but 20 years ago they helped facilitate the disastrous intervention writes George Monbiot in The Guardian

‘Cheerleading for the war in Afghanistan was almost universal, and dissent was treated as intolerable.’ A US marine with evacuees at Kabul airport. Photograph: U.S. Central Command Public Affairs vis Getty Images

‘Cheerleading for the war in Afghanistan was almost universal, and dissent was treated as intolerable.’ A US marine with evacuees at Kabul airport. Photograph: U.S. Central Command Public Affairs vis Getty Images

Everyone is to blame for the catastrophe in Afghanistan, except the people who started it. Yes, Joe Biden screwed up by rushing out so chaotically. Yes, Boris Johnson and Dominic Raab failed to make adequate and timely provisions for the evacuation of vulnerable people. But there is a frantic determination in the media to ensure that none of the blame is attached to those who began this open-ended war without realistic aims or an exit plan, then waged it with little concern for the lives and rights of the Afghan people: the then US president, George W Bush, the British prime minister Tony Blair and their entourages.

Indeed, Blair’s self-exoneration and transfer of blame to Biden last weekend was front-page news, while those who opposed his disastrous war 20 years ago remain cancelled across most of the media. Why? Because to acknowledge the mistakes of the men who prosecuted this war would be to expose the media’s role in facilitating it.

Any fair reckoning of what went wrong in Afghanistan, Iraq and the other nations swept up in the “war on terror” should include the disastrous performance of the media. Cheerleading for the war in Afghanistan was almost universal, and dissent was treated as intolerable. After the Northern Alliance stormed into Kabul, torturing and castrating its prisoners, raping women and children, the Telegraph urged us to “just rejoice, rejoice”, while the Sun ran a two-page editorial entitled “Shame of the traitors: wrong, wrong, wrong … the fools who said Allies faced disaster”. In the Guardian, Christopher Hitchens, a convert to US hegemony and war, marked the solemnity of the occasion with the words: “Well, ha ha ha, and yah, boo. It was … obvious that defeat was impossible. The Taliban will soon be history.”

The few journalists and public figures who dissented were added to the Telegraph’s daily list of “Osama bin Laden’s useful idiots”, accused of being “anti-American” and “pro-terrorism”, mocked, vilified and de-platformed almost everywhere. In the Independent, David Aaronovitch claimed that if you opposed the ongoing war, you were “indulging yourself in a cosmic whinge”.

Everyone I know in the US and the UK who was attacked in the media for opposing the war received death threats. Barbara Lee, the only member of Congress who voted against granting the Bush government an open licence to use military force, needed round-the-clock bodyguards. Amid this McCarthyite fervour, peace campaigners such as Women in Black were listed as “potential terrorists” by the FBI. The then US secretary of state, Colin Powell, sought to persuade the emir of Qatar to censor Al Jazeera, one of the few outlets that consistently challenged the rush to war. After he failed, the US bombed Al Jazeera’s office in Kabul.

The broadcast media were almost exclusively reserved for those who supported the adventure. The same thing happened before and during the invasion of Iraq, when the war’s opponents received only 2% of BBC airtime on the subject. Attempts to challenge the lies that justified the invasion – such as Saddam Hussein’s alleged possession of weapons of mass destruction and his supposed refusal to negotiate – were drowned in a surge of patriotic excitement.

So why is so much of the media so bloodthirsty? Why do they love bombs and bullets so much, and diplomacy so little? Why do they take such evident delight in striking a pose atop a heap of bodies, before quietly shuffling away when things go wrong?

An obvious answer is the old adage that “if it bleeds it leads”, so there’s an inbuilt demand for blood. I remember as if it were yesterday the moment I began to hate the industry I work for. In 1987, I was producing a current affairs programme for the BBC World Service. It was a slow news day, and none of the stories gave us a strong lead for the programme. Ten minutes before transmission, the studio door flew open and the editor strode in. He clapped his hands and shouted: “Great! 110 dead in Sri Lanka!” News is spectacle, and nothing delivers spectacle like war.

Another factor in the UK is a continued failure to come to terms with our colonial history. For centuries the interests of the nation have been conflated with the interests of the rich, while the interests of the rich depended to a remarkable degree on colonial loot and the military adventures that supplied it. Supporting overseas wars, however disastrous, became a patriotic duty.

For all the current breastbeating about the catastrophic defeat in Afghanistan, nothing has been learned. The media still regale us with comforting lies about the war and occupation. They airbrush the drone strikes in which civilians were massacred and the corruption permitted and encouraged by the occupying forces. They seek to retrofit justifications to the decision to go to war, chief among them securing the rights of women.

But this issue, crucial as it was and remains, didn’t feature among the original war aims. Nor, for that matter, did overthrowing the Taliban. Bush’s presidency was secured, and his wars promoted, by American ultra-conservative religious fundamentalists who had more in common with the Taliban than with the brave women seeking liberation. In 2001, the newspapers now backcasting themselves as champions of human rights mocked and impeded women at every opportunity. The Sun was running photos of topless teenagers on Page 3; the Daily Mail ruined women’s lives with its Sidebar of Shame; extreme sexism, body shaming and attacks on feminism were endemic.

Those of us who argued against the war possessed no prophetic powers. I asked the following questions in the Guardian not because I had any special information or insight, but because they were bleeding obvious. “At what point do we stop fighting? At what point does withdrawal become either honourable or responsible? Having once engaged its forces, are we then obliged to reduce Afghanistan to a permanent protectorate? Or will we jettison responsibility as soon as military power becomes impossible to sustain?” But even asking such things puts you beyond the pale of acceptable opinion.

You can get away with a lot in the media, but not, in most outlets, with opposing a war waged by your own nation – unless your reasons are solely practical. If your motives are humanitarian, you are marked from that point on as a fanatic. Those who make their arguments with bombs and missiles are “moderates” and “centrists”; those who oppose them with words are “extremists”. The inconvenient fact that the “extremists” were right and the “centrists” were wrong is today being strenuously forgotten.

‘Cheerleading for the war in Afghanistan was almost universal, and dissent was treated as intolerable.’ A US marine with evacuees at Kabul airport. Photograph: U.S. Central Command Public Affairs vis Getty Images

‘Cheerleading for the war in Afghanistan was almost universal, and dissent was treated as intolerable.’ A US marine with evacuees at Kabul airport. Photograph: U.S. Central Command Public Affairs vis Getty ImagesEveryone is to blame for the catastrophe in Afghanistan, except the people who started it. Yes, Joe Biden screwed up by rushing out so chaotically. Yes, Boris Johnson and Dominic Raab failed to make adequate and timely provisions for the evacuation of vulnerable people. But there is a frantic determination in the media to ensure that none of the blame is attached to those who began this open-ended war without realistic aims or an exit plan, then waged it with little concern for the lives and rights of the Afghan people: the then US president, George W Bush, the British prime minister Tony Blair and their entourages.

Indeed, Blair’s self-exoneration and transfer of blame to Biden last weekend was front-page news, while those who opposed his disastrous war 20 years ago remain cancelled across most of the media. Why? Because to acknowledge the mistakes of the men who prosecuted this war would be to expose the media’s role in facilitating it.

Any fair reckoning of what went wrong in Afghanistan, Iraq and the other nations swept up in the “war on terror” should include the disastrous performance of the media. Cheerleading for the war in Afghanistan was almost universal, and dissent was treated as intolerable. After the Northern Alliance stormed into Kabul, torturing and castrating its prisoners, raping women and children, the Telegraph urged us to “just rejoice, rejoice”, while the Sun ran a two-page editorial entitled “Shame of the traitors: wrong, wrong, wrong … the fools who said Allies faced disaster”. In the Guardian, Christopher Hitchens, a convert to US hegemony and war, marked the solemnity of the occasion with the words: “Well, ha ha ha, and yah, boo. It was … obvious that defeat was impossible. The Taliban will soon be history.”

The few journalists and public figures who dissented were added to the Telegraph’s daily list of “Osama bin Laden’s useful idiots”, accused of being “anti-American” and “pro-terrorism”, mocked, vilified and de-platformed almost everywhere. In the Independent, David Aaronovitch claimed that if you opposed the ongoing war, you were “indulging yourself in a cosmic whinge”.

Everyone I know in the US and the UK who was attacked in the media for opposing the war received death threats. Barbara Lee, the only member of Congress who voted against granting the Bush government an open licence to use military force, needed round-the-clock bodyguards. Amid this McCarthyite fervour, peace campaigners such as Women in Black were listed as “potential terrorists” by the FBI. The then US secretary of state, Colin Powell, sought to persuade the emir of Qatar to censor Al Jazeera, one of the few outlets that consistently challenged the rush to war. After he failed, the US bombed Al Jazeera’s office in Kabul.

The broadcast media were almost exclusively reserved for those who supported the adventure. The same thing happened before and during the invasion of Iraq, when the war’s opponents received only 2% of BBC airtime on the subject. Attempts to challenge the lies that justified the invasion – such as Saddam Hussein’s alleged possession of weapons of mass destruction and his supposed refusal to negotiate – were drowned in a surge of patriotic excitement.

So why is so much of the media so bloodthirsty? Why do they love bombs and bullets so much, and diplomacy so little? Why do they take such evident delight in striking a pose atop a heap of bodies, before quietly shuffling away when things go wrong?

An obvious answer is the old adage that “if it bleeds it leads”, so there’s an inbuilt demand for blood. I remember as if it were yesterday the moment I began to hate the industry I work for. In 1987, I was producing a current affairs programme for the BBC World Service. It was a slow news day, and none of the stories gave us a strong lead for the programme. Ten minutes before transmission, the studio door flew open and the editor strode in. He clapped his hands and shouted: “Great! 110 dead in Sri Lanka!” News is spectacle, and nothing delivers spectacle like war.

Another factor in the UK is a continued failure to come to terms with our colonial history. For centuries the interests of the nation have been conflated with the interests of the rich, while the interests of the rich depended to a remarkable degree on colonial loot and the military adventures that supplied it. Supporting overseas wars, however disastrous, became a patriotic duty.

For all the current breastbeating about the catastrophic defeat in Afghanistan, nothing has been learned. The media still regale us with comforting lies about the war and occupation. They airbrush the drone strikes in which civilians were massacred and the corruption permitted and encouraged by the occupying forces. They seek to retrofit justifications to the decision to go to war, chief among them securing the rights of women.

But this issue, crucial as it was and remains, didn’t feature among the original war aims. Nor, for that matter, did overthrowing the Taliban. Bush’s presidency was secured, and his wars promoted, by American ultra-conservative religious fundamentalists who had more in common with the Taliban than with the brave women seeking liberation. In 2001, the newspapers now backcasting themselves as champions of human rights mocked and impeded women at every opportunity. The Sun was running photos of topless teenagers on Page 3; the Daily Mail ruined women’s lives with its Sidebar of Shame; extreme sexism, body shaming and attacks on feminism were endemic.

Those of us who argued against the war possessed no prophetic powers. I asked the following questions in the Guardian not because I had any special information or insight, but because they were bleeding obvious. “At what point do we stop fighting? At what point does withdrawal become either honourable or responsible? Having once engaged its forces, are we then obliged to reduce Afghanistan to a permanent protectorate? Or will we jettison responsibility as soon as military power becomes impossible to sustain?” But even asking such things puts you beyond the pale of acceptable opinion.

You can get away with a lot in the media, but not, in most outlets, with opposing a war waged by your own nation – unless your reasons are solely practical. If your motives are humanitarian, you are marked from that point on as a fanatic. Those who make their arguments with bombs and missiles are “moderates” and “centrists”; those who oppose them with words are “extremists”. The inconvenient fact that the “extremists” were right and the “centrists” were wrong is today being strenuously forgotten.

Wednesday 6 January 2021

Should bouncers be banned?

Siddharth Monga in Cricinfo

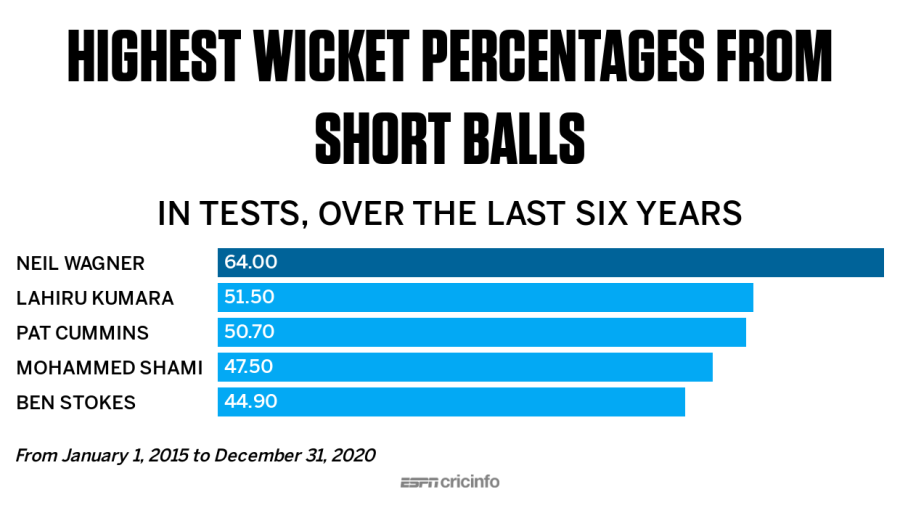

The current India tour of Australia has already had a bowling allrounder, a lower-order batsman, miss the T20I series because of a concussion. A key bowler is missing three Tests of the series with a broken arm. An opening batsman has missed out on a potential Test debut because of a hit to his head, which gave him his ninth concussion before the age of 22. All three players were hit by accurate, high-pace short-pitched bowling, which takes extreme skill, and some luck, to keep out.

The concussed bowling allrounder is now back. He scored a fifty at the MCG that frustrated the home side, who have been accustomed to rolling India over once they lose five wickets. India's additions from five-down in their last six innings in Test cricket: 64, 43, 48, 40, 48, 21. In Melbourne, the sixth wicket alone added 121 because this bowling allrounder hung around with his captain, one of only five specialist batsmen, a bold selection by the visiting side after 36 all out.

The fast bowler whose bouncer in the T20I ended up concussing this allrounder goes back to the bouncer plan in the Test. Experts on TV feel he has been too late getting there, that he has not been nasty enough. The allrounder shows he can handle himself, dropping his wrists and head out of the way of a couple of snorters, but he eventually plays a hook and is caught in the deep.

The next few batsmen are much less adept at handling this kind of bowling - the kind of players who have yielded low returns for India batting lower in the order. Bouncer after bouncer follows. One batsman has to call for help after getting hit in the chest. The other is hit twice on the forearm. All told, the bowler bowls 23 consecutive short balls at Nos. 7-9. Welcome to the land of "broken f****** elbows".

****

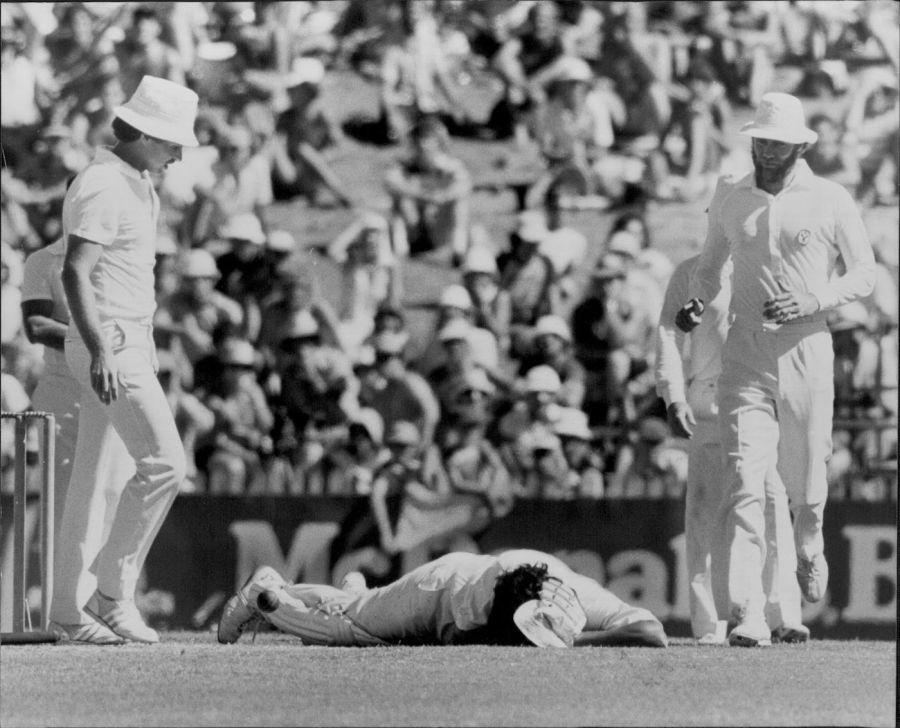

This is Australia. This is the land of tough, "hard but fair" cricket. This is also the place where there was an exemplary inquest into safety standards in cricket after the tragic death of young Phillip Hughes on a cricket field. Hughes was a specialist batsman, it was not a high-pressure Test match, and he was not facing an express bowler. He was hit in the side of the neck by a bouncer, just where the helmet ends.

It was a moment of awakening in cricket; of realisation that we have been extremely lucky, given the number of blows batsmen take, that we have not had too many such grave injuries. That it needn't be an inept tailender, that it needn't be 150kph, that it needn't be particularly nasty at first look, that any of the large number of bouncers we see and enjoy could be fatal for any of the practitioners of this highly skilled sport.

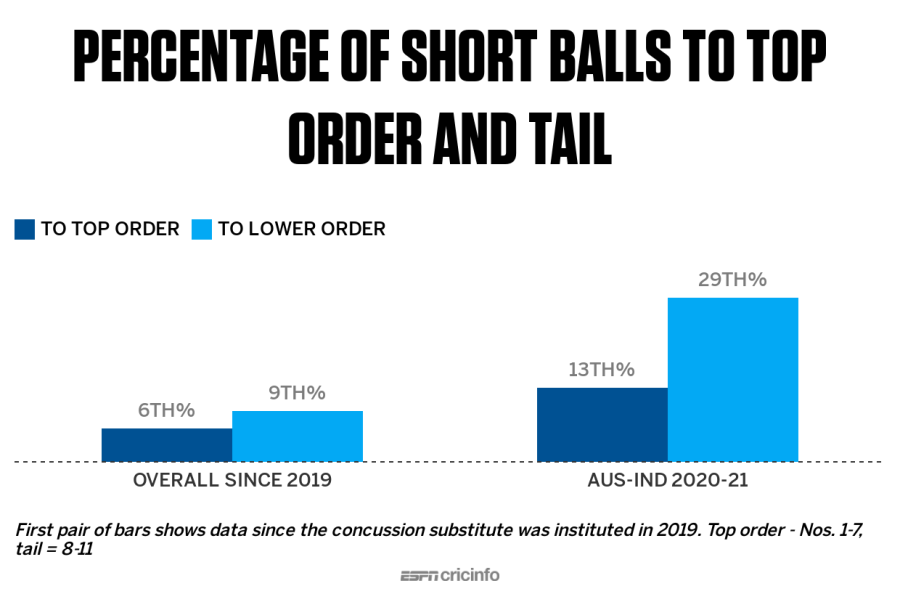

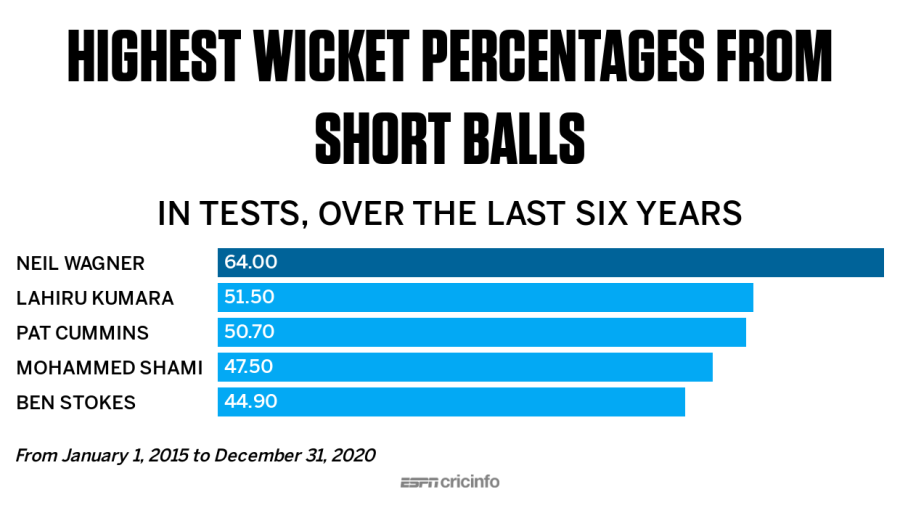

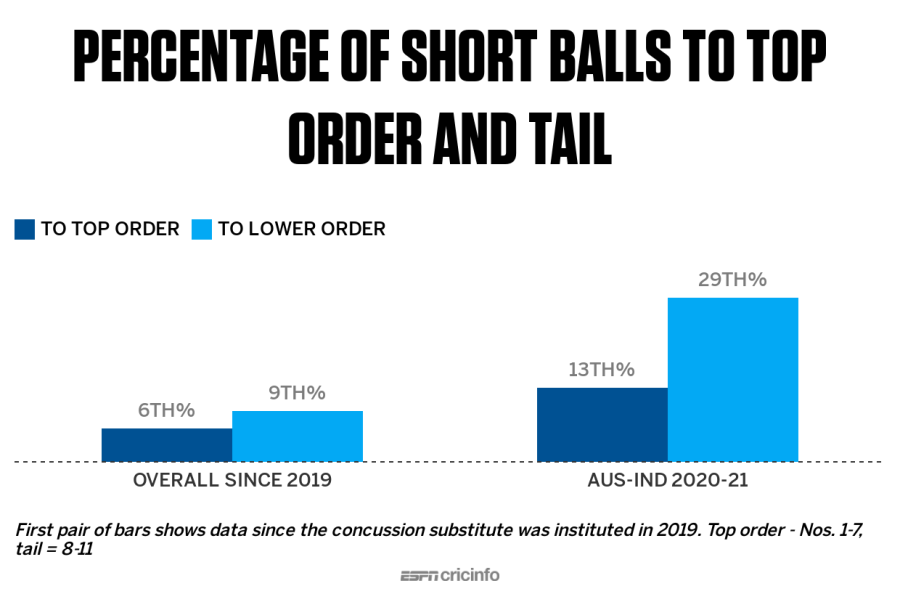

While there is conversation around making cricket safer, the threat for lesser-skilled batsmen is going up: 13% of deliveries from fast bowlers to those batting from Nos. 1 to 7 has been short in this series; for the lesser batsmen, batting from 8 to 11, this number has gone up to a whopping 29%, or roughly two short balls an over. The corresponding numbers in the recently concluded series between New Zealand and West Indies were 9% and 13%, which is still higher than the norm in Test cricket: 6% for batsmen 1 to 7 and 9% for the tail since concussions substitutes were introduced in July 2019.

****

Cricket is a weird sport. If you are a tail-end batsman, you often have to go out and let millions watch you do something you are inept at - sometimes hilariously so. And do it against opponents who are almost lethally good at doing what they are doing. The less you like it, the more you get it.

Opposing fast bowlers have stopped looking after each other now, what with protective equipment improving and lower-order batsmen increasingly placing higher prices on their wickets. When you are hit by a bouncer, you know there are former cricketers, some of whom you grew up idolising, waiting to label you soft should you show pain, let alone walk off.

ESPNcricinfo Ltd

ESPNcricinfo Ltd

****

"The bowling of short-pitched deliveries is dangerous if the bowler's end umpire considers that, taking into consideration the skill of the striker, by their speed, length, height and direction they are likely to inflict physical injury on him/her. The fact that the striker is wearing protective equipment shall be disregarded."

The MCC leaves it to the umpires to decide what is dangerous. In most cases the umpires are professional enough to prevent things from getting bad enough to be visible to those watching from the outside. Often a quiet word when the bowler is walking back to their mark is enough. Yet the times that it does get out of hand, the umpire can call a dangerous delivery a no-ball, followed by a "first and final warning" and suspension from bowling should the bowler repeat the offence. It is near impossible to remember when such a no-ball was called, let alone a suspension.

The one time in recent memory when it did look like it got out of hand was when Brett Lee bowled four straight bouncers at Makhaya Ntini and Nantie Hayward in Adelaide back in 2002. Ntini was hit on the head twice before staggering through for a leg-bye, with Ian Chappell on air observing he was "perhaps a little dazed". After the fourth short ball, which chased Hayward's head as he backed away towards square leg, umpire Simon Taufel had a quiet word, resulting in two full deliveries.

Often under fire from commentators - former players themselves - and fans, umpires can be reluctant to draw any attention to themselves. The common refrain they have to deal with: "They have come to watch us play, not you umpire." Umpires don't want to be seen as overly officious - when it comes to policing player behaviour or in ball management or pitch management or ensuring player safety.