In 2003, the Cabinet Office decided to allow the Chinese state-backed Huawei telecommunications network to start supplying BT for the first time. Nobody bothered to put a note on the security implications into the red box of the then business secretary, Patrica Hewitt. A minor discussion, solely on the competition implications, did take place.

The then head of MI6, Sir Richard Dearlove, used to daily cooperation with BT to secure wire taps, was shocked and concerned when he heard of the plan, but was told: “It is nothing to do with you. These are issues we can control.”

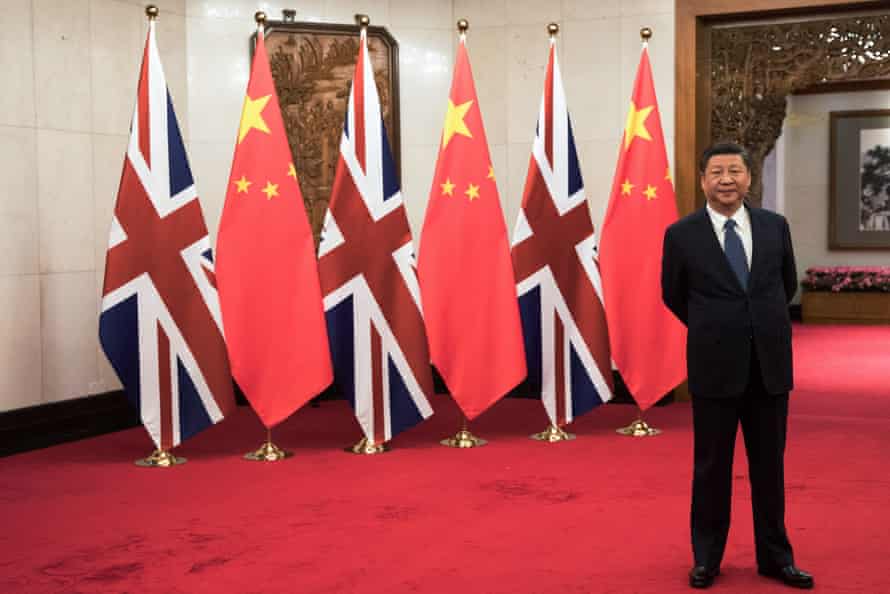

The path was set fair for the open trading relationship with China which reached its zenith with George Osborne and David Cameron in 2015. “No economy in the world is as open to Chinese investment as the UK,” Osborne boasted on a five-day visit to China in September of that year. In a speech to the Shanghai stock exchange, he vowed London would act as China’s bridge to European financial markets. “Whatever the headlines … we shouldn’t be running away from China,” he said. “Through the ups and downs, let’s stick together.”

UK trade with China is worth approximately £7bn, making it Britain’s’s fourth-largest trading partner, the sixth-largest export market and the third-largest import market. By comparison, in 1999 China was the UK’s 26th largest export market and 15th largest source of imports.

But Britain is now veering away from China, despite Osborne’s pledge. It has moved from being China’s greatest advocate in Europe, a wide open door for Chinese investment, into one of its sternest critics. Overall, it represents as swift and complete a reversal in foreign policy as the UK’s shift from treating Russia as an ally in 1945 to cold war foe in 1946.

Yet how this course correction happened, the extent to which it was internally driven, or imposed on the UK by the Trump administration, and whether its limits has been finally set remains largely unresolved.

In the last fortnight alone two major government bills have been published, one aimed primarily at screening out Chinese investment from 17 UK strategic industries, and another cutting Huawei out of the UK telecommunications network entirely from 2027. This reverses the decision taken, in defiance of the US, at the start of the year to give Huawei limited access.

A third bill, in front of the Lords, has been amended in an attempt to prevent any UK trade deals with China if its human rights record is found wanting.

The government’s integrated foreign and security policy review, due in the new year, will contain a British tilt to the Indo-Pacific, shorthand for greater political and military support for the forces of democracy in the South China Sea.

On the Tory benches, the intellectual commanding heights are now dominated by China critics, so much so, it is argued, that Sino-scepticism is the New Euro-scepticism. There is probably no more active group of parliamentarians than the Tory China Research Group, only set up in January. The group, established by Tom Tugendhat, the foreign affairs select committee chairman, and Neil O’Brien, now head of the Conservative policy board, were instrumental in March in mounting the rebellion of 40 MPs who pushed to have Huawei excluded.

Across the Tory thinktanks that matter – Policy Exchange, the Legatum Institute, Henry Jackson Society, – hostility to the Chinese Communist party is unanimous.

Labour, committed to human rights, takes a similar view. It is a British human rights barrister, Rodney Dixon, who is leading the claim that China can be taken to the international criminal court over its treatment of Uighur Muslims. Hong Kong Watch is one of the most active pressure groups defending the steady stream of jailed activists. The UK has become a safe harbour for the exiles, and nearly 60,000 British National (Overseas) passports were handed out to Hong Kongers in September alone.

By contrast the business lobbies, especially finance capital that previously worked assiduously to secure deals with China, have fallen silent, or found themselves struggling for a hearing. British board members on Huawei such as Lord John Browne have resigned. Other former advocates for Huawei such as Alexander Downer, the former Australian high commissioner to London, have long converted, urging the UK to engage with the geopolitical threat posed by China, and “not just see the country as a place to sell Land Rovers and Jaguars”.

Huawei’s own warnings about the potential cost to the UK economy of delaying 5G are ignored.

It can be argued, as Keynes did, that when the facts change, it is advisable to change your mind. The destruction of Hong Kong’s freedoms, China’s secretive mishandling of the coronavirus outbreak, its wolf warrior diplomacy, the revelations about treatment of the Uighur people, the wholesale theft of intellectual property, and the bullying of one of the UK’s natural partners, Australia, has ended illusions about China. In July, the former head of M16 Sir John Sawers wrote that the last six months have “revealed more about China under President Xi Jinping than the previous six years”.

Rory Stewart, the former Foreign Office minister, says: “China has broken a lot of our beliefs about how we thought about things for 200 years. For 200 years there seemed to be a connection between economic growth and liberal democracy. Many, many people thought 20 years ago it was almost inevitable China would move in a liberal, democratic way. Today we are in a much more gloomy place.”

China’s entry into the WTO in December 2001 proved not to be the prelude to the country opening up, but instead a high-water mark.

But these views are now being wrapped into an ideological perception of China as an imperialist power intent on dominating the west technologically, politically and militarily, a view enshrined in a 70-page US state department policy paper entitled Elements of the China Challenge published this month. The paper argues the west utterly misconstrued China as a fledgling economic super power with no imperial ambitions, when in reality “it is determined fundamentally to revise the world order, placing the People’s Republic of China at the centre and serving Beijing’s authoritarian goals and hegemonic ambitions”.

In a lecture given to Policy Exchange, Matthew Pottinger, Donald Trump’s chief adviser on China, drew a sinister portrait. “The party’s overseas propaganda has two consistent themes: ‘We own the future, so make your adjustments now.’ And: ‘We’re just like you, so try not to worry.’ Together, these assertions form the elaborate con at the heart of all Leninist movements.”

It is this kind of thinking deep in the Trump administration that led to the remorseless commercial and political pressure on the UK this summer to change its mind over Huawei.

There are distinctions between the America and British process of disillusionment, according to Sophie Gaston at the British Foreign Policy Group. The US came at the China issue via trade and the loss of manufacturing jobs while the UK came at it primarily through the lens of human rights and national security. But the two views have now blended into a melange of concern about human rights, the race for quantum supremacy and protection of the national infrastructure ranging from power stations to university freedom.

For Martin Jacques, the former British editor of Marxism Today and enthusiastic chronicler of China’s rise, the UK has been gripped by a form of paranoia – reds under the bed replaced by reds under the hard drive. “What’s happening is a very serious regression in the mentality in the UK toward China. It reminds me very much of the cold war. In fact, the thinking is cold war thinking: China is just the evil enemy that has to be rejected. The rightwing reduces China to the communist regime, the communist threat, and the whole Chinese history is lost in the process. So they have no understanding whatsoever of China really. They’ve just got this extraordinary backward view of China, which is just, frankly, plain ignorant. But it’s making the running.”

Another surprising figure despairing at the trend is Vince Cable. The Liberal Democrat was business secretary in the Osborne era and bemoans “the unholy alliance” of Trumpists, neocons, British Conservatives and Labour opposition who, he says, are blowing apart the government’s post-Brexit strategy to invest in China.

But Dearlove kicks back, arguing there is something sinister about China’s methods. He cites three Chinese maxims. “Kill with a borrowed sword – that is, get what you can. Loot a burning house – bear that in mind in terms of taking advantage of the current pandemic. The third one is hide a knife behind a smile.”

China, he says, assembled an influence network in the UK. It “recruited a whole group of leading British business and political figures into that group who were designated cheerleaders for a burgeoning relationship with China. Huawei was an important part of that. The composition – the British membership of the Huawei board – was a very impressive lineup of people who were there to persuade us to drop our guard.”

Quite how far the UK, mired in recession, will go in specific policy terms to distance itself from China, and how China reacts, is in question. The China Research Group in its recent manifesto stops short of Trumpian decoupling of the west from China’s economy, but backs measures including sanctions on UK finance houses operating in Hong Kong that extend the reach of the Communist party, a ban on Chinese state-owned enterprises investing in UK critical infrastructure and a ban on UK firms exporting goods and services that are used to abuse human rights. Tariffs are mentioned only as a last resort.

Some of this is enough to make Lord Grimstone, the former head of Standard Chartered and now a trade minister, blanch. The new China-Britain Business Council chair, and head of public affairs at HSBC, Sir Sherard Cowper-Coles, has also been leading a discreet fightback, pointing out that after Brexit, Britain needs to insert itself into the Asian-Pacific growth area. China, after all, is the economy taking the world out of recession.

So far, the British elite have managed to keep the Liu Xiaoming, the Chinese ambassador, onside. Despite smarting from the Huawei 5G ban, he has not descended into the name-calling disfiguring Chinese relations with Australia. He has not, for instance, like his colleague in Canberra, sent a 14-point checklist of mistakes that the UK must correct.

Instead, he spoke last month to the third China-UK Economic Forum about the continued chances for synergy with UK business. Ahead of the forum, a survey showed continued Chinese enthusiasm to invest in the UK, despite a fall-back in investment due to coronavirus.

The Foreign Office is clearly nervous of being cast in a vanguard role, while Japan and Germany, for instance, allow Huawei into its 5G networks. The UK has not yet sanctioned anyone over Hong Kong, only provided safe haven. The Trump administration by contrast has sanctioned 14 Chinese officials specifically over Hong Kong, including the chief executive, Carrie Lamb.

Britain will also be cautious because it does not want to be left beached on the high tide of Trumpian anti-Chinese rhetoric only to find that tide went out with Joe Biden’s election. Biden is, at a minimum, likely to take a less aggressive unilateral sanctions-based approach to trade, and it is not yet clear if his planned alliance of democratic nations will be explicitly anti-Chinese.

If the Biden administration is interested in re-stabilising the US-China relationship, the UK is likely to want to be in the slipstream of this process, probably using the climate change agenda as the way back in.

After all, the advocates of pragmatic British engagement have not gone away, just gone quiet.

Lord Powell, a former chairman of the China-Britain Business Council and private secretary to Margaret Thatcher, put it succinctly in a lecture last year. He explained: “I have to admit when visiting China, as a I frequently do, I never get the sense that parliamentary democracy is anything like the highest priority for most people. At least at this stage in the country’s development, their priority is material progress, even if it comes at the price of freedom.”

He added: “I know pragmatism is a dirty word in any discussion of ethical values but when the other guy – in this case China – indisputably has the stronger hand, it is prudent not to provoke unwinnable fights.”