|

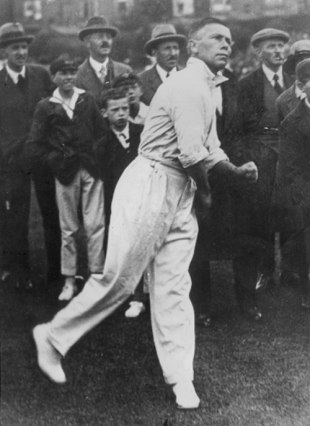

| In the '90s, Australian kids who tried to bowl like Shane Warne often wore themselves out because they weren't built like him © PA Photos |

| Enlarge

|

|

|

|

Shane Warne's first real victim wasn't a batsman, but a fellow legspinner - a fellow Victorian legspinner, in fact, with a wrong 'un so brutal it would crash into the chest of those who lunged blindly forward; a legspinner who ran in like a graceful 1920s medium-pacer, but who then produced a dramatic twirl of his long arms and ripped the ball off the surface like few teenage legspinners before or since. This legspinner was so good that Warne said he had more talent than he did. His name was

Craig Howard. And if you've never heard of him, it's probably not your fault: Howard doesn't even qualify for a single-line biography on ESPNcricinfo.

By December 3, 1995, Warne - who was by then closing in on 200 Test wickets - had already saved legspin. If the date sounds random, then for Howard it was not: it was his

final day of first-class cricket. He was 21. Howard retired with 42 wickets in 16 first-class games at 40 apiece, which was no great shakes. But to understand how good he was, you had to be there - you had to see him hit a batsman with his wrong 'un. Aged 19, he had returned second-innings figures of 24.5-9-42-5

at the MCG against the South Africans.

Wisden noted: "Only Rhodes, with 59, made much of Howard's leg-spin second time around." Darren Berry, who kept to Howard at Victoria, said he would have named him in his all-time XI of those he had played with or against if it hadn't been for Warne. Yes, Craig Howard could definitely bowl.

Plenty of others have been bit parts in the story of Australia's post-Warne spin apocalypse, but no one has been a more intriguing bit part than Howard. He is the only Australian bowler to go through the Cricket Academy twice, once as the artistic legspinning prodigy from my teenage years, later - after one of his fingers packed in - as a 28-year-old, made-to-order journeyman offspinner. And now Howard is back, plucked from his office job in telecommunications to coach Nathan Lyon, currently Australia's No. 1 tweaker.

Howard, as it happened, did play alongside Warne in four Sheffield Shield games in 1993-94. The comparison is unflattering: Warne took 27 wickets at 23, Howard - who bowled 100 overs to Warne's 247 - three at 108. But in between, with Warne away on international duty, Howard finally got a decent bowl: he took 5 for 112

against Tasmania, including the wicket of Ricky Ponting. More than 15 years later, when another leggie - Bryce McGain, who was almost 37 - was making his Test debut for Australia, the 34-year-old Howard was playing for Strathdale Maristians in Bendigo, up-country Victoria.

He is philosophical now. "Had I played Test cricket, my life would have turned out different," he says. "I probably would have ended up in some sextext scandal and lost my wife and kids and ended up a lonely bum. Although, yes, playing Test cricket was the dream."

There are many reasons why Howard didn't make it: injuries, bad management, terrible advice, over-coaching, low self-confidence. But had he played in an era when Australia were desperate for a spinner, he might now be a household name - or at least someone with a decent blurb on the internet.

"At one stage, there were headlines saying I was going to play for Australia," he says. "I remember being about 20, and at the top of my mark at the MCG. Instead of thinking, 'How I am going to get out Jamie Siddons or Darren Lehmann?' I'm thinking about a small group of men in the ground who are judging me. It wasn't like that all the time, but when I was struggling this is how I felt. In the back of my mind I know the captain of my side doesn't like me, and has told me to f*** off to Tasmania. The coach believes that, because I can't bat or field, I am never going to be that useful. It was a dark time."

In the mid-1990s, no one needed to look for Warne's replacement, because he would play for ever and inspire so many kids to take up legspin that any who fell through the cracks wouldn't be missed. Junior sides each had four or five leggies - often with peroxide hair - and they all walked in slowly, ripped the ball hard, and barely bowled a wrong 'un. But they weren't Warne. None had his physicality: Warne was built like a nightclub bouncer, not a spinner. Massive hands led into awe-inspiring wrists, the whole lot powered by an ox's shoulders. But kids who try the same quickly wear themselves out.

Howard knew how they felt: "My body never backed me up. I couldn't feel my pinky finger, had part of my right arm shortened, tendinitis in my shoulder was operated on, a wrist operation, stress fractures in my shins, tennis elbow in my knees from excessive squat thrusts, a spinning finger with bad ligaments, and barely the fitness to get through a two-day game, let alone four. There was no million-dollar microsurgery in the US for me. In the '90s, you still had to pay for a massage and work a day job.

"There were suddenly legspinning experts everywhere - not ex-spinners but just ex-cricketers, coaches and selectors who spent years ignoring legspin. No one ever came up to you and said: 'You should be more like Warne.' But every bit of advice seemed to be about making you more like him. It wasn't subtle. Everything just created doubt in your mind. And with legspin, if you have an ounce of doubt, you're cactus."

Warne's retirement sparked a desperate search for his replacement. One spinner simply begat the next: Stuart MacGill, Brad Hogg, Beau Casson, Cameron White, Jason Krejza, Nathan Hauritz, Marcus North, Bryce McGain, Hauritz again, Steve Smith, Xavier Doherty, Michael Beer, Nathan Lyon. Never mind Simon Katich, Michael Clarke or Andrew Symonds.

MacGill should have softened the blow of Warne's departure, but his knees gave way, his career as a lifestyle-show TV host took off, and it was clear he just didn't want to bowl any more. Even then, there was Hogg, the chinaman bowler with two World Cup wins to his name. But after one horrendous home summer against India, he retired as well - only to make a bizarre return to international cricket during the Twenty20 home series against the Indians once more, in February 2012, aged all but 41.

Along came Casson, another purveyor of chinamen, but a boyish one who seemed too pure for international cricket. His first (and only) Test was uneventful, and within 12 months he would be out of the Australian set-up altogether after an attack of the yips. A brief comeback was ended by tetralogy of Fallot, a congenital heart defect.

White was captain of Victoria, where he virtually never bowled himself, but suddenly - a product of injuries to others and weird selection - he was Australia's frontline spinner. He was awful. Krejza eventually got a chance and, on Test debut

in Nagpur, claimed 12 wickets. The problem was he also gave away 358 runs; he played only one more Test. Marcus North became a Test batsman because he could bowl handy offspin, some said better than Hauritz. But despite a flattering six-wicket haul against Pakistan

at Lord's, North's offbreaks were gentle; and they weren't much help when his batting faded.

McGain made his debut amid plenty of jokes about Bob Holland, who was 38 when he first played for Australia. McGain was an IT professional in a bank, who had never really been especially close to state selection. But he wouldn't go away. And while the search focused on big-turning kids, McGain sneaked into the Victoria side. In the 12 months before his Test debut, a shoulder injury had limited him to four first-class games. When the day finally came, at Newlands, McGain was roadkill: 18-2-149-0. That was it. McGain now plays part-time in the Big Bash League.

Hauritz was not deemed good enough even for New South Wales. He was a timid offspinner from club cricket with a first-class bowling average of more than 50, but he fought hard and improved regularly. The trouble was Hauritz was neither an attacker nor a defender, and Chris Gayle said it was like facing himself. By the time Hauritz was dumped, he was in the best form of his career.

A young allrounder named Steve Smith bowled legspin, and was brought in to play Pakistan in England. He made

a dashing 77, was dropped and then later recalled in the Ashes as a batsman who bowled a bit - just not very well.

Xavier Doherty was given a go because Kevin Pietersen kept falling to left-arm spin. He got his man - but for 227. So in came Michael Beer, who admitted he probably wasn't ready for Test cricket, and then proved it.

Mighty big shoes to fill

| Bowler | Style | Test debut | Matches | Runs | Wkts | BB | Avg | SR | Econ |

| Shane Warne | LBG | 1991-92 | 145 | 17,995 | 708 | 8-71 | 25.41 | 57.49 | 2.65 |

| Brag Hogg | SLC | 1996-97 | 7 | 933 | 17 | 2-40 | 54.88 | 89.64 | 3.67 |

| Stuart MacGill | LBG | 1997-98 | 44 | 6038 | 208 | 8-108 | 29.02 | 54.02 | 3.22 |

| Nathan Hauritz | OB | 2004-05 | 17 | 2204 | 63 | 5-53 | 34.98 | 66.66 | 3.14 |

| Beau Casson | SLC | 2007-08 | 1 | 129 | 3 | 3-86 | 43.00 | 64.00 | 4.03 |

| Cameron White | LBG | 2008-09 | 4 | 342 | 5 | 2-71 | 68.40 | 111.60 | 3.67 |

| Jason Krejza | OB | 2008-09 | 2 | 562 | 13 | 8-215 | 43.23 | 57.15 | 4.53 |

| Marcus North | OB | 2008-09 | 21 | 591 | 14 | 6-55 | 42.21 | 89.85 | 2.81 |

| Bryce McGain | LBG | 2008-09 | 1 | 149 | 0 | 0-149 | - | - | 8.27 |

| Steve Smith | LBG | 2010 | 5 | 220 | 3 | 3-51 | 73.33 | 124.00 | 3.54 |

| Xavier Doherty | SLA | 2010-11 | 2 | 306 | 3 | 2-41 | 102.00 | 151.66 | 4.03 |

| Michael Beer | SLA | 2010-11 | 1 | 112 | 1 | 1-112 | 112.00 | 228.00 | 2.94 |

| Nathan Lyon | OB | 2011-12 | 10 | 832 | 29 | 5-34 | 28.68 | 55.72 | 3.08 |

The first anyone in Australian cricket heard of Nathan Lyon was when Kerry O'Keeffe mentioned him on radio. At that stage, Lyon was part of the Adelaide Oval groundstaff, and was travelling to Canberra to play for the second XI. After some good performances in the nets, Darren Berry - now Adelaide's Twenty20 coach - took a punt on him. Lyon suddenly looked like the best spin prospect in the country - which wasn't saying much.

Howard really had come along at the wrong time. But there were moments, before I finally spoke to him, when I wondered if he actually existed at all. Finding someone who remembered his name was hard enough; finding someone who'd seen him play next to impossible. I'd talk to a guy, who'd tell me to contact a guy, but that guy would also tell me to contact a guy. The leads never went anywhere. Craig Howard wasn't the missing link of Australian spin bowling: he was just missing.

Then I asked Gideon Haigh about Howard, and he gave a long stare, as if he was searching through his billion-terabyte memory. I had my breakthrough. Haigh talked about how Howard looked like an otherworldly artist - long shirt buttoned to the wrist, billowing madly in the wind; incredibly gawky, like a schoolkid. Howard didn't fit into Haigh's, or anyone else's, imaginings of an athlete. But it was the Howard of my youth. Someone else remembered my poet leggie.

After that I cornered O'Keeffe, legspin's court jester. He had coached Howard at the Academy, probably twice. O'Keeffe's eyes were full of regret: he said Howard had a biomechanically flawed action, and O'Keeffe hadn't tried to fix it. But that didn't stop him happily reminiscing about "a wrong 'un batsmen had to play from their earhole".

I collared Damien Fleming, Howard's Victoria colleague. Fleming seemed surprised to hear the name again. He told stories about how he thought Victoria had a champion on their hands, but said his skin folds were thicker than those of Warne or Merv Hughes: "Basically bone and fat." He could have gone further with a more supportive coaching structure, said Fleming. He added, almost lustfully: "The best wrong 'un I've seen." Then came the clincher. "If someone like him came on the scene now, he'd be given everything he needed to succeed. Like they treat Pat Cummins."

Haigh, O'Keeffe and Fleming all seemed to think Howard was a Test spinner we had missed out on. They could be right. But Howard was caught between two eras, relaxed and regimented. And Australia had Warne.

"My career is long over," says Howard. "It finished with me out of form and mostly injured. It wasn't one thing that ended my career, and I'm not coming up with excuses, but this is what happened to me. Due to my finger, I can't even bowl legspin any more - I have to bowl offspin, but nothing can ever compare to being a legspinner. I'm younger than Hogg, McGain or MacGill and instead of preparing to play in my 100th Test and thinking about retirement, I am working in an office in Bendigo."

Craig Howard went from a freakishly talented wrist-spinner to a boring club offie. Australian spin did much the same.