“Blessed is the nation that doesn’t need heroes" Goethe. “Hero-worship is strongest where there is least regard for human freedom.” Herbert Spencer

Search This Blog

Tuesday 13 June 2023

Wednesday 31 May 2023

Saturday 13 May 2023

Imran Khan alone is not to blame

PAKISTAN’S mad rush towards the cliff edge and its evident proclivity for collective suicide deserves a diagnosis, followed by therapy. Contrary to what some may want to believe, this pathological condition is not one man’s fault and it didn’t develop suddenly. To help comprehend this, for a moment imagine the state as a vehicle with passengers. It is equipped with a steering mechanism, outer body, wheels, engine and fuel tank.

Politics is the steering mechanism. Whoever sits behind the wheel can choose the destination, speed up, or slow down. Choosing a driver from among the occupants requires civility, particularly when traveling along a dangerous ravine’s edge. If the language turns foul, and respect is replaced with anger and venom, animal emotions take over.

Imran Khan started the rot in 2014 when, perched atop his container, he hurled loaded abuse upon his political opponents. Following the Panama exposé of 2016, he accused them — quite plausibly in my opinion — of using their official positions for self-enrichment. How else could they explain their immense wealth? For years, he has had no names for them except chor and daku.

But the shoe is now on the other foot and Khan’s enemies have turned out no less vindictive, abusive and unprincipled. They have recorded and made public his recent intimate conversations with a young female, dragged in the matter of his out-of-wedlock daughter, and exposed the shenanigans of his close supporters.

More seriously, they have presented plausible evidence that Mr Clean swindled billions in the Al Qadir and Toshakhana cases. Which is blacker: the pot or the kettle? Take your pick.

Everyone knows politics is dirty business everywhere. Just look at the antics of Silvio Berlusconi, Italy’s corrupt former prime minister. But if a vehicle’s occupants include calm, trustworthy adjudicators, the worst is still avoidable. Sadly Pakistan is not so blessed; its higher judiciary has split along partisan lines.

The outer body is the army, made for shielding occupants from what lies outside. But it has repeatedly intruded into the vehicle’s interior, seeking to pick the driver. Free-and-fair elections are not acceptable. Last November, months after the Army-Khan romance soured, outgoing army chief General Qamar Javed Bajwa confessed that for seven decades the army had “unconstitutionally interfered in politics”.

But a simple mea culpa isn’t enough. Running the economy or making DHAs is also not the army’s job. Officers are not trained for running airlines, sugar mills, fertiliser factories, or insurance and advertising companies. Special exemptions and loopholes have legalised tax evasion and put civilian competitors at a disadvantage.

A decisive role in national politics, whether covert or overt, was sought for personal enrichment of individuals. It had nothing to do with national security.

While Khan has focused solely on the army’s efforts to dislodge him, his violent supporters supplement these accusations by disputing its unearned privileges. When they stormed the GHQ in Rawalpindi, attacked an ISI facility in Pindi, and set ablaze the corps commander’s house in Lahore, they did the unimaginable. But, piquing everyone’s curiosity, no tanks confronted the enraged mobs. No self-defence was visible on social media videos. The bemused Baloch ask, ‘What if an army facility had been attacked in Quetta or Gwadar?’ Would there be carpet bombing? Artillery barrages?

The wheels that keep any economy going are business and trade. Pakistanis are generally very good at this. Their keen sense for profits leads them to excel in real-estate development, mining, retailing, hoteliering, and franchising fast-food chains. But this cleverness carries over to evading taxes, and so Pakistan has the lowest tax-to-GDP ratio among South Asian countries.

The law appears powerless to change this. When a trader routinely falsifies his income tax return, all guilt is quickly expiated by donating a dollop of cash to a madressah, mosque, or hospital. In February, the pious men of Markazi Tanzeem Tajiran (Central Organisation of Traders) threatened a countrywide protest movement to forestall any attempt to collect taxes. The government backed off.

The engine, of course, is what makes the wheels of an economy turn. Developing countries use available technologies for import substitution and for producing some exportables. A strong engine can climb mountains, pull through natural disasters such as the 2022 monster flood, or survive Covid-19 and events like the Ukraine war. A weak one relies on friends in the neighbourhood — China, Saudi Arabia, and UAE — to push it up the hill. By dialling three letters — I/M/F — it can summon a tow-truck company.

The weakness of the Pakistani engine is normally explained away by various excuses — inadequate infrastructure, insufficient investment, state-heavy enterprises, excessive bureaucracy, fiscal mismanagement, or whatever. But if truth be told, the poverty of our human resources is what really matters.

For proof, look at China in the 1980s, which had more problems than Pakistan but which had an educated, hard-working citizenry. Economists say that these qualities, especially within the Chinese diaspora of the 1990s, fuelled the Chinese miracle.

The fuel, finally, is the human brain. When appropriately educated and trained, it is voraciously consumed by every economic engine. Pakistan is at its very weakest here. Small resource allocation for education is just a tenth of the problem.

More importantly, draconian social control through schools and an ideology-centred curriculum cripples young minds at the very outset, crushing independent thought and reasoning abilities. Leaders of both PTI and PDM agree that this must never change. Hence Pakistani children have — and will continue to have — inferior skills and poorer learning attitudes compared to kids in China, Korea, or even India.

The prognosis: it is hard to see much good coming out of a screeching catfight between rapacious rivals thirsting for power and revenge. None have a positive agenda for the country.

While the much-feared second breakup of Pakistan is not going to happen, the downward descent will accelerate as the poor starve, cities become increasingly unlivable, and the rich flee westwards. Whether or not elections happen in October and Khan rises from the ashes doesn’t matter. To fix what has gone wrong over 75 years is what’s important.

Saturday 6 May 2023

Tuesday 25 April 2023

Young people are wising up to the Great British student rip-off – and they’re voting with their feet

The tradition of scholars teaching academic subjects part-time while doubling as researchers is a relic of medieval monasticism. Oxbridge operates for just 24 weeks a year while many other universities operate two semesters. Staff and buildings may be otherwise employed, but students will sit idle, doing odd jobs or studying on their own. No one dares challenge this system. Whitehall inspectors never declare universities “failing” or “inadequate” as they do schools.

But I sense the worm is turning. Last year the percentage of British school leavers going to university fell for the first time – other than briefly in 2012, when the £9,000 fees came in in England. Even before lockdown and the years of online-only teaching, an Ipsos Mori poll showed a falling demand for university among school-leavers, with just 32% being “very likely” to go in 2018. The same trend is evident in the US where college enrolments have been falling for over a decade.

Meanwhile industrial and professional apprenticeships are rising fast. At Lloyds Bank last year, 17,000 school-leavers applied for 215 vacancies. The exam bluff was called by EY’s Maggie Stilwell, who said there was “no evidence” to conclude that exam success correlated with career success. Personal qualities and professional training were what mattered. Her firm, along with accountants PwC and Grant Thornton, have dropped any requirement of degree classes or even A-level results from their application forms. The new “degree apprenticeships” offered by firms such as Dyson and Rolls-Royce are popular, with some 30,000 offered last year. The Institute of Student Employers records that a declining half of firms now ask for a class of degree, and a quarter explicitly state “no minimum requirements”. In Silicon Valley it is even known that an acceptance letter from Stanford University can be sufficient to secure a job. Why waste years swotting for meaningless exams?

The age-old debate over whether a university is really an investment, personal or national, as opposed to a middle-class finishing school has never been resolved. British graduates on average earn £10,000 more than their non-graduate contemporaries, but surely some students might have done equally well with the same number of years’ work under their belts, perhaps studying a favourite subject part- or full-time later in life.

During his brief career as universities minister, Jo Johnson at least hinted at radicalism. He questioned the one-size-fits-all residential university. He floated shorter courses, shorter holidays, broader subjects, more intensive teaching and lifelong learning. He might have added that artificial intelligence is posing a whole new challenge. Johnson may now have gone, but the marketplace is talking. This most reactionary of British institutions may yet be forced to waken from the sleep of ages.

Saturday 25 March 2023

Ofsted Rating Grades and The Consequences For Teaching

Lucy Kellaway in The FT

Last Monday a primary school headteacher took to Twitter and declared that Ofsted inspectors, who were due the next day, would not be let in. She invited teachers everywhere to join a protest in solidarity with Ruth Perry, the primary head who recently took her own life — her family attribute it to an Ofsted inspection that downgraded her school from outstanding to inadequate.

Though the mass protest was called off and the inspectors duly admitted, the verdict online was damning and unanimous. End inspections! End Ofsted! — everything teachers are angry about seems to be crystallised in the tragic death.

That morning I was in the cinema at a local shopping centre with my A-level students for a spot of business studies revision. On the screen was a question. Which was the odd one out: a) salary b) working conditions c) supervision or d) meaningful work?

Most went for meaningful work, recognising that the others were “hygiene factors”, identified by the American psychologist Frederick Herzberg as basic requirements which, if inadequate, demotivate us and make us want to quit. Meaningful work, by contrast, is a motivator — it makes us try harder.

So here we were: my colleague and I surrounded by teenagers in leggings and hoodies on a happy, productive day out, living proof of that motivator. Like every teacher I’ve ever met, we enjoy being with our charges (most of them, most of the time). We think helping them learn is as meaningful as a job can be.

Yet the profession is in a sorry state. According to new figures from the NFER research body, recruitment is at least 20 per cent below target in many subjects, with vacancies running at twice pre-Covid levels. Worse, almost half of existing teachers are planning an exit within five years.

The hygiene factors are all worsening simultaneously. Cuts in real pay and impossible workloads have brought teachers out on strike. Budget cuts in other services have left vulnerable children all but unsupported, turning us into de facto social workers. This inspection crisis seems like the last straw.

On joining the profession I was taught to fear Ofsted. In previous schools I filled in endless curriculum spreadsheets in precisely the way the inspectorate is believed to favour — no opposition brooked — and watched supervisors trudge home every weekend to complete “Ofsted-ready” folders. I’ve lived through “mocksteds” — expensive, stressful and even more vicious than the real thing — designed to reassure stressed-out school leaders that they are prepared.

In my current school, that call came not so long ago: Ofsted inspectors were on their way. At lunchtime one of my sixth-formers asked why her teachers were acting so oddly. Because we feel our jobs are on the line, I wanted to say. Because if we get the same treatment as Ms Perry, it will be a disaster for the school. Because we feel judged, on the back foot and exhausted — but are trying our best.

I daresay I was acting pretty peculiar as the inspector stationed himself at the back of my class and started taking notes in an unnervingly deadpan fashion. In the end, it was without mishap. The process felt professional, the questions reasonable and the feedback fair. With hindsight, it strikes me the fear and loathing stems less from the inspection itself, than from the nonsense of summarising a complex school in a single grade — with so much at stake.

Creating intense competition between schools may (or may not) have raised standards for students. But in many schools it has made life grim for teachers, especially senior ones. Schools bust a gut to have the best Ofsted grades and top the league tables, but those that make it can be unbearable places to work: hierarchical, workaholic factories.

In these feted schools, where students get dazzling exam results, the teachers who quit are often not the worst, but the best. The more they are promoted, the more they are in the line of fire. A brilliant young teacher I trained with said recently that she envied me — not because of my inimitable teaching style, but because of my steadfast position on the bottom rung of the career ladder. I’m too junior to be much affected by Ofsted or bear responsibility for things outside my control. I am not entirely dependent on my teaching salary so can afford to resist the pay rise that comes with promotion. I’m largely immune from the hygiene factors — and left free to enjoy teaching average rate of return to my Year 11s.

Changing hygiene factors is hard. The government is not fond of finding extra money. Reducing workload isn’t easy either. But sweeping away the Ofsted grades would allow teachers to remind themselves why they joined the profession: for the sake of their wonderful (and maddening) students, not a badge that says “outstanding”.

Friday 16 December 2022

Sunday 14 August 2022

Friday 12 August 2022

Saturday 2 July 2022

Brain Power - Israel's Secret Weapon

IS it some international conspiracy — or perhaps a secret weapon — that allows Israel to lord over the Middle East? How did a country of nine million — between one-half and one-third of Karachi’s population — manage to subdue 400m Arabs? A country built on stolen land and the ruins of destroyed Palestinian villages is visibly chuckling away as every Arab government, egged on by the khadim-i-haramain sharifain, lines up to recognise it. Economically fragile Pakistan is being lured into following suit.

Conspiracy theorists have long imagined Israel as America’s overgrown watchdog, beefed up and armed to protect American interests in the Middle East. But only a fool can believe that today. Every American president, senator and congressman shamefacedly admits it’s the Israeli tail that wags the American dog. Academics who chide Israel’s annexation policies are labelled anti-Semitic, moving targets without a future. The Israeli-US nexus is there for all to see but, contrary to what is usually thought, it exists for benefiting Israel not America.

It was not always this way. European Jews fleeing Hitler were far less welcome than Muslims are in today’s America. That Jewish refugees posed a serious threat to national security was argued by government officials in the State Department to the FBI as well as president Franklin Roosevelt himself. One of my scientific heroes, Richard Feynman, was rejected in 1935 by Columbia University for being Jewish. Fortunately, MIT accepted him.

What changed outsiders into insiders was a secret weapon. That weapon was brain power. Regarded as the primary natural resource by Jews inside and outside Israel it is an obsession for parents who, spoon by spoon, zealously ladle knowledge into their children. The state too knows its responsibility: Israel has more museums and libraries per capita than any other country. Children born to Ashkenazi parents are assumed as prime state assets who will start a business, discover some important scientific truth, invent some gadget, create a work of art, or write a book.

In secular Israel, a student’s verbal, mathematical, and scientific aptitude sets his chances of success. By the 10th grade of the secular bagut system, smarter students will be learning calculus and differential equations together with probability, trigonometry and theorem proving. Looking at some past exam papers available on the internet, I wondered how Pakistani university professors with PhDs would fare in Israeli level-5 school exams. Would our national scientific heroes manage a pass? Unsurprisingly, by the time they reach university, Israeli students have bettered their American counterparts academically.

There is a definite historical context to seeking this excellence. For thousands of years, European anti-Semitism made it impossible for Jews to own land or farms, forcing them to seek livelihoods in trading, finance, medicine, science and mathematics. To compete, parents actively tutored their children in these skills. In the 1880s, Zionism’s founders placed their faith solidly in education born out of secular Renaissance and Enlightenment thought.

But if this is the story of secular Israel, there is also a different Israel with a different story. Ultra-orthodox Haredi Jews were once a tiny minority in Israel’s mostly secular society. But their high birth rate has made them grow to about 10 per cent of the population. Recognisable by their distinctive dress and manners, the Haredim are literally those who “tremble before God”.

For Haredis, secularism and secular education are anathema. Like Pakistan, Israel too has a single national curriculum with a hefty chunk earmarked for nation-building (read, indoctrination). In the Israeli context, the ideological part seeks to justify dispossession of the Palestinian population. Expectedly, the ‘Jewish madressah’ system accepts this part but rejects the secular part ie that designed to create the modern mind.

The difference in achievement levels between regular and Haredi schools is widening. While all schools teach Hebrew (the holy language), secular schools stress mastery over English while ‘madressahs’ emphasise Hebrew. According to a Jerusalem Post article, Haredi schools (as well as Arab-Israeli schools) are poor performers with learning outcomes beneath nine of the 10 Muslim countries that participated in the most recent PISA exam. A report says 50pc of Israel’s students are getting a ‘third-world education’.

The drop in overall standards is causing smarter Israelis to lose sleep. They fear that, as happened in Beirut, over time a less fertile, more educated elite sector of society will be overrun by a more fertile, less-educated religious population. When that happens, Israel will lose its historical advantage. Ironically, Jewish identity created Israel but Jewish orthodoxy is spearheading Israel’s decline.

There is only one Muslim country that Israel truly fears — Iran. Although its oil resources are modest, its human resources are considerable.

The revolution of 1979 diminished the quality of Iranian education and caused many of Iran’s best professors to flee. But unlike Afghanistan’s mullahs, the mullahs of Iran were smart enough to keep education going. Although coexistence is uncomfortable, science and religion are mostly allowed to go their own separate ways. Therefore, in spite of suffocating embargos, Iran continues to achieve in nuclear, space, heavy engineering, biotechnology, and the theoretical sciences. Israel trembles.

Spurred by their bitter animosity towards Iran, Arab countries have apparently understood the need of the times and are slowly turning around. Starting this year, religious ideology has been de-emphasised and new subjects are being introduced in Saudi schools. These include digital skills, English for elementary grades, social studies, self-defence and critical thinking. Of course, a change of curriculum means little unless accompanied by a change of outlook. Still, it does look like a beginning.

Israel has shown the effectiveness of its secret weapon; it has also exposed the vulnerability of opponents who don’t have it. There are lessons here for Pakistan and a strong reason to wrest control away from Jamaat-i-Islami ideologues that, from the time of Ziaul Haq onward, have throttled and suffocated our education. The heights were reached under Imran Khan’s Single National Curriculum which yoked ordinary schools to madressahs. But even with Khan’s departure, ideological poisons continue to circulate in the national bloodstream. Until flushed away, Pakistan’s intellectual and material decline will accelerate.

Sunday 8 May 2022

Thursday 17 March 2022

Forget ‘essential’, hijab isn’t that Islamic. Muslim women just made Western tees ‘halaal’

In the Arabic lexicon and the Quran, the word ‘hijab’ means a curtain, not a veil or a scarf. According to Asma Lamrabet, a Moroccan Islamic feminist, the term is reiterated seven times in the Quran, referring to the same meaning each time. “Hijab means curtain, separation, wall, and in other words, anything that hides, masks, and protects something,” she says. Never in Islamic history was this word used for a garment or a piece of clothing.

Product of new culture

The hijab, in its current form, is not older than two decades in India. As late as 2001, when this scribe stumbled upon an online matrimonial ad in which an American Muslim woman had said, “I wear hijab”, he, reasonably well-versed in Islamic idioms, couldn’t help wondering how hijab could be worn at all. He wasn’t aware that the said word had become a terminology that connoted a stylised head bandage worn to emphasise that the wearer belonged to a different religion and community and that she prided in her difference from those around her who did not belong to the same faith.

Although couched in the discourse of modesty, this was clearly a marker of identity, which soon became the uniform for religious assertion in societies where Islam wasn’t the dominant political force. The politics of this sartorial semiotics was neither lost on its proponents nor those who came to resent it.

Whether the case for hijab is argued from the vantage point of religiosity or identity, in neither case the proffered arguments could be regarded as liberal and secular. So, why can’t the liberal-secular intelligentsia tell the supporters of hijab that their insistence on displaying religious symbols in sanitised public spaces like schools is illiberal, un-secular, regressive, and militant? After all, wouldn’t it eventually harm those the most who have the greatest stake in India’s liberal secularism — the Muslim minority? Is it because the liberals, having completely lost the script and unable to fight their own battle, have been counting on the Muslim identitarian politics to keep them in the reckoning? Have they developed the same vested interest in Muslim communalism as did the British earlier?

Not a choice

Two key terminologies that have been bandied about liberally (pun intended) during the ongoing controversy — one in affirmation and the other in negation — are ‘choice’ and ‘patriarchy’. It has been argued that wearing any dress is a matter of individual choice. Of course, it is. However, one might ask whether the votaries of the hijab concede this right to all women to wear any dress of their choice. Would the very girls who have been exercising their “individual choice” to wear the hijab to school be able to walk freely, if they so chose, without it through their Muslim neighbourhoods and not compromise their families’ honour or invite opprobrium on themselves?

Hijab is not an individual choice, it’s a communal compulsion.

The pace at which it has been spreading hints that the day is not far when Muslim women not conforming to it may no longer be recognised as Muslims. This is what was going to happen if the Karnataka High Court’s judgement had gone the other way.

Equally insidious has been the narrative that the assertive display of the hijab is a setback to Islamic patriarchy. Far from it. Both in form and content, and very consciously too, this trend signifies the revival of orthodoxy, including its patriarchal presumptions. The religious sanction for man’s supremacy and his right to decide for women is not being questioned. Instead, what rankles is the loss of political supremacy of the supposed Muslim community. Muslim women, too, are supposed to have suffered from this loss.

Therefore, they, instead of seeking equality with men, are engaged in the higher pursuit of reviving supremacy over other religions. Their gender is not only secondary to Islam, but, as seen in the use of the hijab as a tool of religious assertion, also deployed in service of the religion. The capability and agency gained as blessings of education and modernity are ploughed back into the religious-political discourse.

Towards communal visibility

Another myth being circulated is that the hijab is an enabler for education, which is to say that had it not been for the hijab, Muslim girls wouldn’t be able to go out for studies. The fact, however, is that till the very end of the 20th century — before it became a common sight — most Muslim girls attended schools and colleges dressed in the same attire as other girls. The same trend would have continued if religious radicalisation had not permeated the socio-political atmosphere.

Therefore, before educating Muslim women on the hijab, so that a case could be made for the latter’s essentiality, our liberal-secular intelligentsia should have done better to wonder why an outer covering over the regular dress, which was not considered necessary earlier, became a precondition for going for studies.

This is despite the fact that the nature of the Muslim woman’s modest dressing underwent a change through the years. Before the head-wrap became trendy wear, there were three moot questions — Should a Muslim woman freely go out of her house? Should her face be covered with the naqaab? Can she, like men at home, wear Western attire?

The new hijab took care of all the questions. Women could go out. The face was exposed, but instead, the head and the neck had to be covered in a particular style, and, if topped with the hijab, Western dresses such as jeans and tee shirts became halaal.

Hijab replaced the earlier invisibility of the Muslim woman with a hypervisibility of her religious identity. Whether this identity should compulsively be asserted in public spaces is the question that Indian Muslims need to resolve wisely.

Sunday 6 March 2022

Thursday 17 February 2022

Sunday 13 February 2022

Saturday 12 February 2022

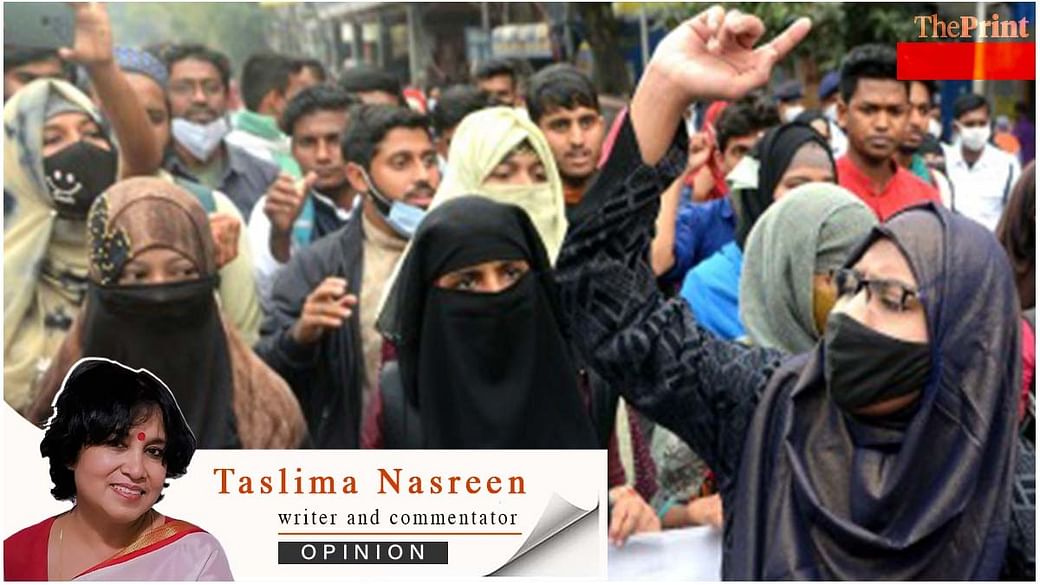

Muslim women must see burqa is just like chastity belt of dark ages, Taslima Nasreen writes

Taslima Nasreen in The Print

There is practically no difference between a Jewish, Christian, Muslim or Hindu fundamentalist. They are all primarily ‘intolerant’. Standing next to the mortal remains of playback singer Lata Mangeshkar, Muslims have prayed to Allah, Hindus to Bhagwan, and Christians to their almighty God. Seeing Bollywood icon Shah Rukh Khan lifting his hands in prayer and blowing on her body, some Hindu extremists thought that he was spitting. Then social media mayhem descended.

I have noticed that in India, while Muslims are largely aware of Hindu rituals and practices, most Hindus are ignorant about Muslims ones. Similarly in Bangladesh, Hindus understand Muslim rituals more than what Muslims know of Hindus.

To a large extent, intolerance stems from ignorance. As we saw in the Shah Rukh Khan incident, people from all religions stood behind him. In fact, there are enough liberal and rational people in the Hindu community to oppose the extremists.

The row over hijab

An unnecessary controversy over hijab has erupted in another part of the country, Karnataka. After authorities raised objection to female students from wearing hijab to colleges, the protest by Muslim students started. Then, a group of students donning saffron scarves, took to the streets protesting against the burqa. Chief Minister Basavaraj Bommai ordered schools and colleges to remain shut for a few days. But this is not a solution. If the state fears riots, then violence can erupt when schools and colleges reopen. To prevent riots, the mindset needs to change, and hatred and fear for each other need to be washed clean. In this regard, the Karnataka High Court’s interim order makes sense. I believe, uniform civil code and uniform dress code are necessary to stop conflicts. Right to religion is not above the right to education.

The distance between Hindus and Muslims has not been bridged even after 75 years of Partition. Pakistan has separated from India and has turned into a religious state. But India never wanted to become a Pakistan. Or it could have easily turned into a Hindu State 75 years ago. The Indian Constitution upholds secularism, not religion. This country, with a majority Hindu population, is home to the second largest Muslim population in the world. The laws of India give equal rights to people from all religions, castes, languages, creeds, and cultures.

It is perfectly all right for an educational institution in a secular country to mandate secular dress codes for its students. There is nothing wrong in such a message from the school/college authority that states that religion is to be practised within the confines of the home. Educational institutions, meant for fostering knowledge, are not influenced by religion or gender. It is education that can lift people from the abyss of bigotry, baseness, conservativeness and superstitions into a world where the principles of individual freedom, free-thinking, humanism and rationality based on science is valued highly.

In that world, women do not feel pride in their shackles of subjugation but rather break free from them, they do not perceive covering themselves in a burqa as a matter of right but as a symbol of female persecution and cast them away. Burqas, niqabs, hijabs have a singular aim of commodifying women as sex objects. The fact that women need to hide themselves from men who sexually salivate at the sight of women is not an honourable thought for both women and men.

Education is supreme

Twelve years ago, a local newspaper in Karnataka published an article of mine on burqa. Some Muslim fundamentalists vandalised the office and burnt it down. They also burnt down shops and businesses around it. Hindus also hit the streets in protest. Two people died when the police opened fire. A simple burqa can still cause fire to burn in this state. Riots can still break out over burqas.

A burqa and hijab can never be a woman’s choice. They have to be worn only when choices are taken away. Just like political Islam, burqa/hijab is also political today. Members of the family force the woman to wear the burqa/hijab. It is a result of sustained brainwashing from a tender age. Religious apparel like the burqa/hijab can never be a person’s identity, which is created by capabilities and accomplishments. Iran made hijab compulsory for women. Women stood on the streets and threw away their hijabs in protest. The women of Karnataka, who still consider hijab as their identity, need to strive harder to find a more meaningful and respectable identity for themselves.

When a woman’s right to education is violated on the pretext of her wearing a hijab, when someone forces a woman out of hijab as a precondition to education, I stand in favour of education even in hijab. At the same time, when a woman is forced to wear a hijab, I stand in favour of throwing the hijab away. Personally I am against hijab and burqa. I believe it is a patriarchal conspiracy that forces women into wearing burqa. These pieces of clothing are symbols of oppression and insult to women. I hope women soon realise that burqa is not different from the chastity belt of the dark ages that was used to lock in women’s sexual organs. If chastity belts are humiliating, why not burqa?

Some say that the furore over the burqa in Karnataka is not spontaneous and is supported by political forces. This sounds very familiar to saying that riots do not happen, but are manufactured — mostly before elections and almost always between Hindus and Muslims. Apparently they do count for a few votes. I, too, was thrown out of West Bengal for a few votes.

It is heartening that riots do not happen. It would be frightening if they did happen spontaneously. Then we would have surmised that Hindus and Muslims are born enemies and can never live with each other peacefully.

I believe that even the Partition riots didn’t happen on their own but were made to happen.

A new India

I have heard some Hindu fanatics call for India to be turned into a Hindu Rashtra, where non-Hindus will be converted to Hinduism or be forced to leave the country.

I really do not know if such people are big in numbers. I know India as a secular state and love it that way. I have confidence in the country. Is India changing? Will it change? I am aware of the liberality of Hinduism as a religion. One is free to follow or not follow it. Unlike in Islam, Hinduism does not force one to follow its practices. Hinduism doesn’t prescribe people to torture, imprison, behead, hack or hang someone to death for blasphemy. Superstitions still exist in Hinduism, even though a lot has waned with time. But, India will be a country only for Hindus, anyone criticising Hindus or Hindutva will be killed — are statements that are new to me.

I have been critically scrutinising all religions and religious fundamentalism in order to uphold women’s rights and equality for more than three decades now. My writings on Hinduism and religious superstitions suppressing women’s rights have been published in Indian newspapers/magazines and have also been appreciated. But today, as soon as I pose a question like, “Why do men not observe Karva Chauth for the welfare of women?” hundreds of Hindus hurl personal attacks and abuse on me demanding my expulsion from the country. This is a new India. An India that I cannot imagine. I find their behaviour similar to Muslim fundamentalists. Utterly intolerant.

If India was a Hindu Rashtra, will all fundamentalists and liberal Hindus be able to live peacefully? Will there be no discontent among the dominant and oppressed castes, no discrimination between men and women? A state only for Hindus? Perhaps. Just the way Jews have carved a state for themselves, and Muslims have Pakistan.

I will have to leave a Hindu Rashtra too because I cannot become a Hindu. I am an atheist and a humanist, and I choose to stay that way. Gauri Lankesh, I believe, was a humanist. She was not fit for a Hindu Rashtra, nor will I be.

Friday 11 February 2022

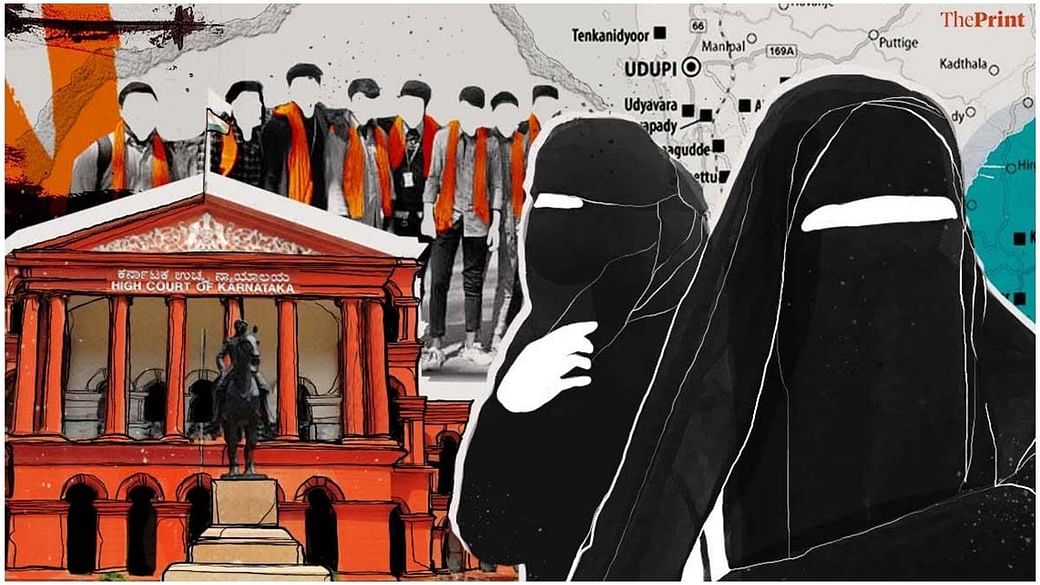

"The Inside Story on The Hijab - School case"

Anusha Ravi Sood in The Print

Udupi: Abdul Shukur took a sip of water and bit into a chikki (peanut bar) at 6:30pm Tuesday. It was his first meal after a day-long fast and he had come to offer prayers at the Jamia Masjid in Udupi, Karnataka. Shukur’s daughter, Muskaan Zainab, studies at the city’s Government Pre-University (PU) College and is one of several students who have petitioned the Karnataka High Court for the right to wear the hijab (headscarf) on campus.

“Our entire family fasted today since our petition was being heard in court. I will fast tomorrow too,” 46-year old Shukur, who runs a small business in Malpe, said.

The hijab row has been making headlines since January, but Shukur claimed the issue was triggered in October when viral photos showed Muslim girls at a protest organised by the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP, the RSS-affiliated students’ body).

The images in question were posted on the Facebook page of the Udupi ABVP on 30 October last year. They showed Muslim girls holding the ABVP flag as part of a protest demanding a probe into the alleged rape of a Manipal student. In the communally sensitive coastal belt of Karnataka, the pictures ignited a controversy.

“I was taken aback to see my daughter there… because she isn’t a member of ABVP,” Shukur said. Furthermore, Muskaan was not wearing her usual headscarf in the photo.

“I asked her why she wasn’t wearing a headscarf in the photo, and that is when she told me that the college doesn’t allow hijabs in classrooms,” he said. This came as a shock to Shukur, who decided to confront the college principal.

He was not the only one taking notice. According to an intel report submitted by the Udupi police to the state government, the Campus Front of India (CFI), which is the students’ wing of the Islamist outfit Popular Front of India (PFI), had approached parents with the offer to help take on the college management.

A source from the CFI who did not wish to be named told ThePrint that the ABVP protest incident had outraged the organisation. It therefore started encouraging Muslim women to refuse to join ABVP events and to fight for their right to wear hijabs in the classroom. The women’s parents also took these demands to the college.

“When I asked the principal why students were being sent to protest without consent and were not allowed to wear headscarves, he said it was a small issue,” Shukur said.

Rudre Gowda, principal of the college, rejected this allegation. “For years, students have been wearing hijabs to campus, but have been removing them during classes. These girls too were adhering to this, but since December, they started demanding that hijab should be allowed during classes too,” Gowda told ThePrint.

The matter quickly led to a standoff between the families of six Muslim students and the college management. The CFI also alleged that the college had, as retaliation, made details of the girls and their families public.

While there were attempts to negotiate an understanding between the students and the college authorities in Udupi, the row escalated rapidly — partly due to political organisations jumping on to the bandwagon and partly due to the wildfire effect of social media.

In January, the students petitioned the Karnataka High Court, by which time the issue was making headlines and had snowballed into communally charged conflicts in several Karnataka colleges.

Also Read: A timeline of how hijab row took centre stage in Karnataka politics and reached HC

Bruised egos and social media hype

Before the hijab issue reached the headlines, there were weeks of efforts to forge an understanding between the families and the college.

A senior leader of the Udupi District Muslim Okkoota — an umbrella organisation of mosques, jamaats, and Islamic organisations in Udupi — told ThePrint on the condition of anonymity that the body had tried its best to convince the families that it was acceptable to remove the hijab in class.

“We advised the girls to not make a big issue out of not wearing hijab inside classrooms. We even took them and their parents to religious clerics and explained that it was okay to remove hijabs in the classroom,” he said.

However, the students were “adamant”, he said, because they had received backing from the CFI, the campus affiliate of the PFI, an Islamist outfit that was set up in Kerala in 2006 and which the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) wants banned because of its allegedly radical tendencies.

“The CFI saw [the hijab conflict] as an opportunity to strengthen its support base,” the Muslim Okkoota leader said. In coastal Karnataka, he explained, the two main students’ bodies are the ABVP and CFI, while the Congress’s campus body, the National Students Union of India (NSUI), does not have a presence in local colleges.

When ThePrint spoke to CFI members in Udupi, they claimed that the organisation got involved only after students of the PU College approached them on 27 December, after their memorandums to the district commissioner and education department officials did not yield results. The students in question also told ThePrint that they were not members of the CFI. However, at least three parents are members of the PFI’s political wing, the Social Democratic Party of India (SDPI).

By the end of December, though, nobody was in the mood for a compromise, according to the Muslim Okkoota leader. He said that the Muslim women’s protest, and the social media traction it got, riled the College Development Committee (CDC), which is empowered by the government to take administrative decisions for public educational institutions.

“In December and January, the students’ protests started getting attention on social media and the press. They were shown standing outside the classroom and making notes since they were not allowed inside. This hurt the egos of the committee members,” he claimed, adding that the senior-most members of this body were members of the BJP and RSS. None of the 21 members in the CDC are from the Muslim community.

The matter had now become a “prestige issue” with the BJP and other Hindutva organisations on one side, and the PFI and its affiliates on the other, the Muslim Okkoota leader said.

BJP vs. PFI

What both Hindutva and Muslim organisations can agree on is that as videos from Udupi went viral, they sparked protests in other districts too. Throughout January and February, Karnataka saw several face-offs in colleges between some students in hijabs and others wielding saffron scarves. Each side holds the other responsible.

BJP leaders maintain that without “instigation” from the PFI, the protests wouldn’t have reached such a magnitude.

“Within two days of the girls’ protest in January outside their classrooms, thousands of social media posts were released. How is that possible without a pre-planned, strategised effort?” V. Sunil Kumar, Minister for Energy and Kannada & Culture, told ThePrint.

“When [Muslim students] started escalating the matter, naturally, students from the Hindu community retaliated — a matter of action and reaction,” Kumar, who is also the MLA from Karkala in Udupi district, added.

Other BJP ministers in the Basavaraj Bommai cabinet have also made similar allegations against the PFI. “Students are being instigated to protest for hijab. The role of the PFI and its student wing CFI will be probed thoroughly,” B.C. Nagesh, Karnataka Minister of Primary & Secondary Education, told reporters Tuesday.

The PFI has denied such allegations and has attempted to distance itself from the row.

“As an organisation, we are working for upliftment of marginalised communities. We are in no way involved in this row. Our student wing (CFI) is only trying to provide moral support to aggrieved students. Communal flareups only benefit the BJP,” Anis Ahmed, national general secretary of the PFI, told ThePrint.

The CFI has acknowledged that it was helping the Muslim women’s agitation in Udupi’s PU College, but denied having any political motives.

“We are a student organisation. We do not have any links with political parties. We are leading the students who are fighting for their rights. Muslim students have been harassed at that institute for years now. This is not a retort that erupted overnight,” Masood Manna, a committee member of CFI Udupi, told ThePrint.

Also Read: The right answer to the wrong hijab question is still a wrong answer

Why the PFI and its affiliates are so controversial

The PFI is the organisational successor of the Kerala-based National Development Front (NDF) and claims to fight for social justice for Muslims, particularly in the southern states of Kerala, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu.

In 2010, the political wing of the PFI — the Social Democratic Party of India (SDPI) — was registered with the Election Commission. Since then, it has slowly been making inroads in the coastal Karnataka belt. It had one of its biggest triumphs in the December 2021 elections to 58 Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) in Karnataka, when it won six seats.

The CFI, meanwhile, is popular among Muslim students in three districts of coastal Karnataka — Udupi, Dakshin Kannada and Uttar Kannada. The CFI has actively eaten into the popularity of the Congress’s student wing, the NSUI, in the three districts.

However, the PFI has faced allegations of radicalism from the BJP. In April last year, the Union government told the Supreme Court that it was in the process of banning the PFI, claiming that many office-bearers had links with the now banned Student Islamic Movement of India (SIMI). Chargesheets have also been filed against members of PFI over their alleged involvement in various instances of unrest, which the organisation has dismisses as “baseless”.

Notably, some Muslim community leaders also have reservations about the PFI and its branches. The senior Muslim Okkoota leader who was quoted earlier alleged that the hijab protests seemed to be a ploy by the organisation’s political wing to mobilise support.

“All the Muslim girls use the same vocabulary… ‘fundamental rights’, ‘constitutional issue’, ‘hijab is intrinsic to Islam’. While they may have been wearing hijab for years, the words and phrases that are being publicly said are coming from one source,” the Muslim Okkuta leader claimed.

Allegations of “instigation”, however, have also been levelled against Hindutva organisations, which have started a counter-agitation involving saffron shawls and scarves, and an influx into colleges of ‘protesters’ who are not even students.

Doubling down on the hijab

“Perhaps one or two Muslim girls used to wear hijab to college but now the number has drastically increased. They are doing this to assert their religious identity,” Halady Srinivas Poojari, MLA for Kundapur, told ThePrint. He isn’t far off the mark, although there are varying interpretations of why exactly the women are doing so.

According to Abdul Aziz Udyavar, organising secretary of the Udupi District Muslim Okkoota, the fight over the right to wear the hijab has inspired other girls from the community to exercise their constitutionally guaranteed freedoms. “Just because I was not exercising my right before doesn’t mean I shouldn’t do it in the future,” Udyavar said.

Principals of at least three colleges in Kundapur told ThePrint that while some Muslim students had always worn the hijab to classes, the number had increased ever since the row took off in January.

“There is no explicit rule that bans hijab in the college, but there is no rule that permits it either,” Naveen Shetty, principal of R.N. Shetty College, said.

According to him, students who sought permission to wear hijabs earlier could usually do so “as long as it doesn’t cause trouble”. Now, Shetty said, it was causing trouble and so hijabs as well as saffron scarves were banned in the college. “The management decided to ban both explicitly until the time the high court order comes,” Shetty added.

The Udupi PU College students who petitioned the court told ThePrint that they shouldn’t have to choose between their education and wearing a hijab, but said their stance has come at a cost to them.

Abdul Shukur, Muskaan’s father, said he was concerned for the family’s safety. Another student, A.H. Almas, told ThePrint about the hostility that she was encountering.

“When we started protesting, our details were leaked and unknown people follow us around,” she alleged, adding that members of the CFI were giving the women protection.

The Muslim Okkoota had until recently refrained from openly backing the hijab cause but has now reconsidered its decision. “When Muslim girls who are studying at co-ed colleges that have allowed hijab for years started getting targeted, we had to step in since it is injustice being meted out to them,” Ibrahim Sahib Kota, president of the Udupi Muslim Okkoota, said.

‘Senior VHP, Bajrang Dal, Hindu Jagaran Vedike leaders oversee saffron scarf distribution’

When ThePrint visited Mahatma Gandhi Memorial (MGM) College in Udupi, students wearing hijabs were engaged in a face-off with others who had donned saffron scarves and headgear. But, when ThePrint spoke to many of the Hindu protestors, they admitted they were no longer students of the college.

“I studied commerce here and passed out in the 2016-2017 academic year,” Sushanth sheepishly told ThePrint, identifying himself as an ABVP member. “For many years, [Muslim women students] have been wearing hijabs in classrooms but now since they are making a strong assertion of their religious right, should we not as Hindus assert our religious identity too?” he asked, insisting that the protesting Hindu students had all brought their own saffron scarves and shawls.

ThePrint, however, witnessed male protestors distributing saffron shawls to women students who had just arrived at the college. The scene was in line with a couple of videos that went viral this month: One showed students returning their saffron headgear to purported members of the Hindu Jagaran Vedike near their college, and another showed someone in an Innova car distributing saffron scarves to students at a college in Kodagu.

Another protestor, Akshat Pai, said he had graduated from the college in 2014, but was there in his capacity as a Hindu Jagaran Vedike leader. “We haven’t pressured the students into protesting. They are doing it on their own,” Akshat Pai said, as students in saffron accessories hovered around him and asked whether they should leave or stay.

A first-year B.Com. student, a Hindu woman, told ThePrint on the condition of anonymity that many of the protestors did not study at the college. “Why are outsiders coming and supplying saffron scarves to our collegemates?” she asked, adding that she had no problem with the hijab just as her Muslim friends had no objection to the bindi on her forehead.

Harshita, another Hindu student at MGM college, had a different viewpoint. She cited a 5 February government order proscribing clothes that “disturb public law and order” and said that if Muslim women could wear hijabs, Hindus could wear saffron scarves.

Prakash Kukkehalli, Mangaluru unit general secretary of the Hindu Jagaran Vedike, was observing the protest at MGM college from the other side of the road, with young men from the campus occasionally arriving to consult with him.

“We are not instigating students. We are only giving them moral support,” Kukkehalli told ThePrint.

According to him, the PFI, SDPI, and other Muslim organisations were provoking students for political benefit. “They have launched social media warfare to dent the image of India,” he said. “Today they will ask for hijab, tomorrow it will be Sharia law… a separate nation.”

A former ABVP office-bearer, who did not want to be named, told ThePrint how the saffron scarf protest is orchestrated by Hindutva organisations.

“The saffron scarves are procured and distributed by office bearers. Senior leaders of the VHP, Bajrang Dal, Hindu Jagarana Vedike even visit protest sites to observe whom to groom as a leader and if anyone is straying away from discussed slogans or statements,” he said.

This former ABVP leader added that he did not believe in this kind of “communal activism”, whether from Hindus or Muslims, since it only harmed students’ prospects.

“Student activists should be fighting for better colleges, professional courses and employment — not this hijab or saffron scarf fight,” he said.

A deputy superintendent-rank police officer from Udupi told ThePrint that the police were aware of saffron scarves being handed out to students, but that this was not a crime. “Just before students arrive at their colleges, saffron scarves are being handed to them but that is not an offence,” the police officer said.

Over the past few days, though, the protests have taken a more violent turn. The police arrested 15 people in Shivamogga and Bagalkot districts Tuesday. Last week, police in Kundapur, Udupi, arrested two people, Abdul Majeed and Rajab, who were carrying knives near Kundapur Government PU College.

Communally sensitive belt of Karnataka

The three districts of coastal Karnataka — Dakshin Kannada, Uttar Kannada, and Udupi —are often counted among the more communally sensitive regions in India. All three districts have a sizeable population of Muslims as well as Christians.

“There are at least a hundred communal violence incidents in Udupi and Dakshin Kannada alone annually,” Suresh Bhat Bakrabail, an activist of the Karnataka Communal Harmony Forum (which keeps a track of communal violence incidents in coastal Karnataka) told ThePrint. In 2021, in a four-year high, there were more than 120 such incidents in these two districts alone.

Social activists attribute the frequent communal flare-ups in the region, which is frequently described as a “Hindutva laboratory“, largely to incitement from radical Hindu and Muslim organisations.