Gary Younge in The FT

Every now and then much of Britain discovers racism in much the same way that teenagers discover sex. The general awareness that it is out there collides with the urgent desire to find out where. People talk about it endlessly and carelessly, unsure of what to say or think or whether they are doing it right. They have lots of questions but, even if they did know whom to ask, they would be too crippled by embarrassment to reveal their ignorance. Everyone has an opinion but only a few have any experience. The interest never goes away, though its intensity wanes as they explore other things.

The trouble is not everyone gets to move on. Black people, and other minorities, do not have the luxury of a passing interest in racism. It is their lived reality. A YouGov poll of black, Asian and minority ethnic Britons surveyed over the past two weeks reveals the extent to which prejudice and discrimination is embedded in society.

It found that two-thirds of black Britons have had a racial slur directly used against them or had people make assumptions about their behaviour based on their race. Three-quarters have been asked where they’re “really from”. (When I once told a man I was born in Hitchin, he asked, “Well where were you from before then?”).

More than half say their career development has been affected because of their race, or that they have had people make assumptions about their skills based on their race; 70 per cent believe the Metropolitan police is institutionally racist; and the proportion of black people who have been racially abused in the workplace (half) is almost the same proportion as those who have been abused in the street.

Little wonder then that two-thirds of black people polled think there is still a “great deal” of racism nowadays. This is not a substantial difference from the three-quarters who say they think there was a great deal around 30 years ago.

As the public gaze shifts from the Black Lives Matter protests, these experiences will endure. They may be tempered by greater sensitivity; but heightened consciousness alone will not fix what ails us. The roots are too deep, the institutions too inflexible, the opportunism too prevalent and the cynicism too ingrained to trust the changes we need to goodwill and greater understanding alone.

I applaud the proliferation of reading lists around issues of race and the spike in sales for the work of black authors — people could and should be better informed. But we did not read our way into this and we won’t read our way out. The racism we are dealing with isn’t a question of a few bad apples but a contaminated barrel. It’s a systemic problem and will require a systemic solution.

This is a crucial moment. The nature of the protests thus far has been primarily symbolic — targeting statues and embassies, taking a knee and raising a fist. That ought not to be dismissed. Symbols should not be disregarded as insubstantial. They denote social value and signify intent. But they should not be mistaken for substance either, lest this moment descend into a noxious cocktail of posturing and piety.

Concrete demands do exist. All Black Lives UK, for example, has called for the scrapping of section 60, which gives the police the right to stop and search, and the abolition of the Met police’s gangs’ matrix, an intelligence tool that targets suspected gang members. It also wants measures to address health disparities, particularly relating to black women and mental health, and the implementation of reviews that already exist, including the Lammy Review (on racial disparities in the criminal justice system), the Timpson Review (on school exclusions), and the McGregor-Smith review (race in the workplace).

But the only demand that has cut through has been the push for the education system to more accurately reflect our colonial past and diversity. The poll finds this has the support of 81 per cent of black people — the same percentage that approved of removing a statue of the slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol. (Far from wishing to “photo shop” our cultural landscape, as the prime minister claims, they want their kids to learn more about it. They just don’t want the villains put on a pedestal.)

This is great, as far as it goes but, given the size of the constituency that has been galvanised in the past few weeks and the awareness that’s been raised, it doesn’t go nearly far enough.

The solemn declarations of intent and solidarity that flooded from corporations and governments will leave us drowned in a sea of racial-sensitivity training unless they are followed up by the kind of thoroughgoing change and investment that seeks to genuinely tackle inequalities in everything from housing and education to recruitment, retention and promotion. That costs money and takes guts; it means challenging power and redistributing resources; it requires reckoning with the past and taking on vested interests.

“When people call for diversity and link it to justice and equality, that's fine,” the black radical Angela Davis once told me. “But there’s a model of diversity as the difference that makes no difference, the change that brings about no change.”

The governing body of Oxford university’s Oriel College did not resolve to take down its statue of Cecil Rhodes because they suddenly realised that he was a colonial bigot. They did so because it had become more of a liability to keep it up than to take it down. Similarly, it was not new information about police killings that prompted the National Football League in America to change its position on taking a knee. They did that because the pressure was too great to resist. We have to keep that pressure up, albeit in different ways.

“If there is no struggle there is no progress,” argued the American abolitionist, Frederick Douglass. “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.”

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label discrimination. Show all posts

Showing posts with label discrimination. Show all posts

Saturday, 27 June 2020

Thursday, 11 June 2020

It's time we South Asians understood that colourism is racism

What should we feel, and I ask my fellow South Asians this, having heard Daren Sammy raise the issue of being called kalu by his IPL team-mates? Horror and shame?

It is easy to imagine the befuddlement among some of his former team-mates. That was racist? Weren't - and aren't - we all buddies? Wasn't someone called a motu and someone else a lambu? What about all the camaraderie, and where was the offence when we were all having a jolly time?

How horrified and ashamed are we, really? Have we not thought, even in passing, that this could be a case of dressing-room banter being conflated with racism? And can we, hand on heart, say that we are completely surprised the things Sammy says happened did happen?

Once we have played all these questions in our minds, only one remains: how do we not know that this is so horribly wrong? It's not about whether Sammy knew the meaning of the word; it's about what his team-mates didn't know.

To address this, we must first widen the scope beyond Sammy and Sunrisers Hyderabad. We are at an extraordinary moment in history where a black man being publicly choked to death by a figure of authority has not only sparked worldwide mass outrage, but has also created a heightened sense of awareness about discrimination on the basis of colour, and led to the re-examination of a wide range of social behaviours.

To find the explanation for how it became okay for a group of international cricketers to address - in terms of endearment, they may add - a black West Indian player as kalu, we must face one of the most insidious practices in South Asian culture: colourism.

The elevation of whiteness is not a subcontinental phenomenon. The idea has been seeded over centuries, through religion, cultural imagery, and most profoundly, language, that "white" connotes everything pristine, pure and fair (consider the word "fair" itself) and that "dark" represents everything sinister. Watch Muhammad Ali take this on with cutting simplicity here.

But to understand how this idea originated and grew in the subcontinent, which suffered over 200 years of colonial subjugation and still suffers caste-based discrimination, one must sift through complex layers of sociocultural conditioning based on the regressive dynamics of class, caste, sect and gender. The hierarchy of skin colour is all pervasive in the region, and it doesn't strike most as odd, much less repugnant, that lightness of complexion should be so deeply linked to ideas of beauty.

This idea has been reinforced over decades through popular culture. You need to look no further than mainstream cinema in India: how many of our successful actors, especially women, are representative of the median South Asian skin tone? In the matrimonial pages, fair skin is peddled as a clinching eligibility factor, and consequently, ads for fairness creams position them as agents of salvation and success. So organically is this drilled into the mass subconscious that the obsession has ceased to be offensive: it is merely aspirational.

Add to this another subcontinental abomination - the practice of addressing people by their physical attributes - and you have a recipe for something utterly toxic. These terms of address are demeaning but normalised by a coating of endearment: jaadya or motu for the heavy-set, chhotu or batka for the short, kana for those who squint, and quite seamlessly, kalu or kaliya for those with skin tones darker than that of the majority.

This would perhaps explain Sarfaraz Ahmed's mild bemusement at the outrage over his "Abey kaale" remark to Andile Phehlukwayo in Durban last year. Ahmed, then Pakistan's captain, was speaking in Urdu, so it was apparent that he didn't expect Phehlukwayo, the South Africa allrounder, to understand the sledge, and that anyone familiar with the culture in Pakistan would have understood that he did not intend it as a racial slur.

But it can't be emphasised more that racist utterances are no longer about intent, because intent is so organically and inextricably loaded into the words themselves that it is no longer acceptable to explain them away with "It was not intended to be racist, or to cause hurt or offence." It's for all of us to internalise, more so for public figures: offence not meant is not equal to offence not given or received.

It is easy to imagine the befuddlement among some of his former team-mates. That was racist? Weren't - and aren't - we all buddies? Wasn't someone called a motu and someone else a lambu? What about all the camaraderie, and where was the offence when we were all having a jolly time?

How horrified and ashamed are we, really? Have we not thought, even in passing, that this could be a case of dressing-room banter being conflated with racism? And can we, hand on heart, say that we are completely surprised the things Sammy says happened did happen?

Once we have played all these questions in our minds, only one remains: how do we not know that this is so horribly wrong? It's not about whether Sammy knew the meaning of the word; it's about what his team-mates didn't know.

To address this, we must first widen the scope beyond Sammy and Sunrisers Hyderabad. We are at an extraordinary moment in history where a black man being publicly choked to death by a figure of authority has not only sparked worldwide mass outrage, but has also created a heightened sense of awareness about discrimination on the basis of colour, and led to the re-examination of a wide range of social behaviours.

To find the explanation for how it became okay for a group of international cricketers to address - in terms of endearment, they may add - a black West Indian player as kalu, we must face one of the most insidious practices in South Asian culture: colourism.

The elevation of whiteness is not a subcontinental phenomenon. The idea has been seeded over centuries, through religion, cultural imagery, and most profoundly, language, that "white" connotes everything pristine, pure and fair (consider the word "fair" itself) and that "dark" represents everything sinister. Watch Muhammad Ali take this on with cutting simplicity here.

But to understand how this idea originated and grew in the subcontinent, which suffered over 200 years of colonial subjugation and still suffers caste-based discrimination, one must sift through complex layers of sociocultural conditioning based on the regressive dynamics of class, caste, sect and gender. The hierarchy of skin colour is all pervasive in the region, and it doesn't strike most as odd, much less repugnant, that lightness of complexion should be so deeply linked to ideas of beauty.

This idea has been reinforced over decades through popular culture. You need to look no further than mainstream cinema in India: how many of our successful actors, especially women, are representative of the median South Asian skin tone? In the matrimonial pages, fair skin is peddled as a clinching eligibility factor, and consequently, ads for fairness creams position them as agents of salvation and success. So organically is this drilled into the mass subconscious that the obsession has ceased to be offensive: it is merely aspirational.

Add to this another subcontinental abomination - the practice of addressing people by their physical attributes - and you have a recipe for something utterly toxic. These terms of address are demeaning but normalised by a coating of endearment: jaadya or motu for the heavy-set, chhotu or batka for the short, kana for those who squint, and quite seamlessly, kalu or kaliya for those with skin tones darker than that of the majority.

This would perhaps explain Sarfaraz Ahmed's mild bemusement at the outrage over his "Abey kaale" remark to Andile Phehlukwayo in Durban last year. Ahmed, then Pakistan's captain, was speaking in Urdu, so it was apparent that he didn't expect Phehlukwayo, the South Africa allrounder, to understand the sledge, and that anyone familiar with the culture in Pakistan would have understood that he did not intend it as a racial slur.

But it can't be emphasised more that racist utterances are no longer about intent, because intent is so organically and inextricably loaded into the words themselves that it is no longer acceptable to explain them away with "It was not intended to be racist, or to cause hurt or offence." It's for all of us to internalise, more so for public figures: offence not meant is not equal to offence not given or received.

The silence of victims mustn't be misread. It does not mean willing acceptance. In most cases, they have no choice. They often find themselves outnumbered in social groups - or in dressing rooms - and choose to belong, rather than to confront. Former India opening batsman Abhinav Mukund brought this to light a few years ago with a poignant post on Twitter about how he had to "toughen up" against "people's constant obsession" with his skin colour. In a dressing-room scenario, where the eagerness to conform is far more acute, and where a culture of bullying isn't alien, the compulsion to grin and bear these "friendly" jibes is even more severe.

It doesn't have to be. It might take years, perhaps generations, to reform societies, but sports can do it much more easily through sensitisation and education. In Ahmed's case, it was staggering that a captain of an international team did not understand the enormity of using those words against a black South African cricketer. Cricket boards and franchises now have elaborate programmes to educate players about match-fixing and drug abuse, and in some cases, media management. Adding cultural sensitisation to the list would be a small task but a big step.

Calling somebody kalu in the subcontinent might not feel racist in the way the world understands it. But even without the scars of slavery and subjugation, colourism carries some of the worst features of racism; it is discriminatory, derogatory and dehumanising.

The right response to Sammy is not to question why he didn't raise the matter at the time. He has already explained that he didn't understand what the word meant. It is not even about establishing guilt and punishment. The whole episode must lead to an enquiry into our own prejudices. Cricketers are not only role models and flag bearers of the spirit of their sport. They are also, more than ever before, global citizens, and ignorance shouldn't count as an excuse or serve as a shield.

Sunday, 7 June 2020

Britain is not America. But we too are disfigured by deep and pervasive racism

Yes, it would be foolish to see only parallels in the US and UK experience. But to downplay our own problems would be shameful writes David Olusoga in The Guardian

FacebookTwitterPinterest The British actor John Boyega speaks to the crowd during a Black Lives Matter protest in Hyde Park on 3 June 2020 in London, England. Photograph: Justin Setterfield/Getty Images

Yet in the immediate aftermath of Floyd’s death there was little reason to imagine anything would be any different this time around. For African Americans, one of the most appalling aspects of Floyd’s murder was that they had seen it all before. The same story with the same outcome, all that changed was the name of the victim – Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Sandra Bland, Tamir Rice, Philando Castile, Walter Scott.

For many black Britons, Floyd’s death stirred memories of another list of names, those of the members of their community killed or rendered disabled in similar circumstances at the hands of the British police or immigration officers. On Tuesday, the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton, south London – the closest thing we have in this country to a museum to the black British experience – tweeted the names and the photographs of some of them – Mark Duggan, Sheku Bayoh, Sean Rigg, Sarah Reed, Cherry Groce, Leon Briggs, Christopher Alder, Brian Douglas.

Yet almost instantly a predictable chorus of voices, emanating from predictable corners of British public life, rose up to dismiss the whole thing as an irrelevance. Using a familiar playbook, they accused those black Britons who see reflections of their own situation in the experiences of African Americans of making false comparisons.

The US situation is unique in both its depth and ferocity, they say, so that no parallels can be drawn with the situation in Britain. The smoke-and-mirrors aspect of this argument is that it attempts to focus attention solely on police violence, rather than the racism that inspired it. Those who make it usually point to the ubiquity of firearms in US law enforcement, as proof that the US reality is beyond meaningful comparison. But firearms had nothing to do with the killing of George Floyd. Neither were they a factor in the death of Freddie Gray or the sidewalk killing of Eric Garner, who, like Floyd, pleaded for his life, saying 11 times to the officers who pinned him down: “I can’t breathe”, the same words Floyd used in his final moments. Nor were guns involved in many of the cases when black people have died in custody or during arrest in Britain.

Excusing or downplaying British racism with comparisons to the US is a bad habit with a long history

When black Britons draw parallels between their experiences and those of African Americans, they are not suggesting that those experiences are identical. Few people would deny that in many respects life is better for non-white people in the UK than in the US. The problem is that it is not as “better” as some like to believe. Black men are stopped and searched at nine times the rate of white men. Black people make up 3% of the population of England and Wales but account for 12% of the prison population and not since 1971 have British police officers been prosecuted for the killing of a black man, and even then they were charged with the lesser crime of manslaughter and that charge was later dropped.

To say that the racism that infects parts of our police force and criminal justice system is less virulent than that which poisons the lives of 40 million African Americans is not much of a boast. Is that really the extent of our ambition – to be a somewhat less racist nation than one led by a man who describes white nationalists and members of the Ku Klux Klan as “very fine people”? Surely we who dwell in what the actor Laurence Fox recently assured us is “the most tolerant, lovely country in Europe” have higher hopes?

Excusing or downplaying British racism with comparisons to the US is a bad habit with a long history. It began in 1807, with the abolition of the slave trade and picked up steam three decades later with the end of British slavery, twin events that marked the beginning of 200 years of moral posturing and historical amnesia. The Victorian readers who rightly wept over Uncle Tom’s Cabin, for example, conveniently forgot which nation had carried his ancestors into slavery and didn’t dwell on the fact that most of the cotton produced by American slaves like him was shipped to Liverpool.

For two centuries, we have deployed American racism as a distraction. It’s as if we find it easier to recognise American forms of racism than we do our own home-grown varieties. Convenient, as pointing fingers is always more comforting than looking in the mirror.

Demonstrator at a Black Lives Matter protest on 6 June 2020 in Cardiff. Photograph: Matthew Horwood/Getty Images

One of the more pertinent statements made during this past extraordinary week appeared in one of the last places I would have thought to look – in the pages of Vogue, not a publication I instinctively turn to at a moment of profound political tension.

“Racism is a global issue. Racism is a British issue. It is not one that is merely confined to the United States – it is everywhere, and it is systemic,” wrote Edward Enninful, the editor-in-chief of the magazine’s British edition. The ubiquity of racism has been brought to stark and sudden attention by the killing of George Floyd and by the unprecedented wave of protests, demonstrations and rioting that followed.

Filmed by many witnesses and now viewed millions of times, the killing of Floyd by a Minnesota policeman, a 21st-century lynching, is so sickening a crime that the revulsion it has induced has become a global phenomenon.

The demonstrators and activists who have taken to the streets have, however, been motivated by more than revulsion. They have also been stirred to action by acknowledging a fundamental truth – that the killing of Floyd has to be understood as a symptom of systemic racism. By building their campaign around that reality they have promoted radical and challenging conversations – in countries on both sides of the Atlantic – about the nature of racism and the actions that people of all races can take in eliminating it. These are conversations that we have needed for a very long time.

Led by young people, many of them inspired by Black Lives Matter, and involving people of all ethnicities, the protests have morphed into a worldwide anti-racist movement. No longer is this moment solely about police violence nor is it limited to America. Both online and on the streets it is calling out racism, wherever it exists and in whatever forms it is found. In both the US and in Europe, people are asking, tentatively, if this might be a defining moment of change.

One of the more pertinent statements made during this past extraordinary week appeared in one of the last places I would have thought to look – in the pages of Vogue, not a publication I instinctively turn to at a moment of profound political tension.

“Racism is a global issue. Racism is a British issue. It is not one that is merely confined to the United States – it is everywhere, and it is systemic,” wrote Edward Enninful, the editor-in-chief of the magazine’s British edition. The ubiquity of racism has been brought to stark and sudden attention by the killing of George Floyd and by the unprecedented wave of protests, demonstrations and rioting that followed.

Filmed by many witnesses and now viewed millions of times, the killing of Floyd by a Minnesota policeman, a 21st-century lynching, is so sickening a crime that the revulsion it has induced has become a global phenomenon.

The demonstrators and activists who have taken to the streets have, however, been motivated by more than revulsion. They have also been stirred to action by acknowledging a fundamental truth – that the killing of Floyd has to be understood as a symptom of systemic racism. By building their campaign around that reality they have promoted radical and challenging conversations – in countries on both sides of the Atlantic – about the nature of racism and the actions that people of all races can take in eliminating it. These are conversations that we have needed for a very long time.

Led by young people, many of them inspired by Black Lives Matter, and involving people of all ethnicities, the protests have morphed into a worldwide anti-racist movement. No longer is this moment solely about police violence nor is it limited to America. Both online and on the streets it is calling out racism, wherever it exists and in whatever forms it is found. In both the US and in Europe, people are asking, tentatively, if this might be a defining moment of change.

FacebookTwitterPinterest The British actor John Boyega speaks to the crowd during a Black Lives Matter protest in Hyde Park on 3 June 2020 in London, England. Photograph: Justin Setterfield/Getty Images

Yet in the immediate aftermath of Floyd’s death there was little reason to imagine anything would be any different this time around. For African Americans, one of the most appalling aspects of Floyd’s murder was that they had seen it all before. The same story with the same outcome, all that changed was the name of the victim – Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Sandra Bland, Tamir Rice, Philando Castile, Walter Scott.

For many black Britons, Floyd’s death stirred memories of another list of names, those of the members of their community killed or rendered disabled in similar circumstances at the hands of the British police or immigration officers. On Tuesday, the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton, south London – the closest thing we have in this country to a museum to the black British experience – tweeted the names and the photographs of some of them – Mark Duggan, Sheku Bayoh, Sean Rigg, Sarah Reed, Cherry Groce, Leon Briggs, Christopher Alder, Brian Douglas.

Yet almost instantly a predictable chorus of voices, emanating from predictable corners of British public life, rose up to dismiss the whole thing as an irrelevance. Using a familiar playbook, they accused those black Britons who see reflections of their own situation in the experiences of African Americans of making false comparisons.

The US situation is unique in both its depth and ferocity, they say, so that no parallels can be drawn with the situation in Britain. The smoke-and-mirrors aspect of this argument is that it attempts to focus attention solely on police violence, rather than the racism that inspired it. Those who make it usually point to the ubiquity of firearms in US law enforcement, as proof that the US reality is beyond meaningful comparison. But firearms had nothing to do with the killing of George Floyd. Neither were they a factor in the death of Freddie Gray or the sidewalk killing of Eric Garner, who, like Floyd, pleaded for his life, saying 11 times to the officers who pinned him down: “I can’t breathe”, the same words Floyd used in his final moments. Nor were guns involved in many of the cases when black people have died in custody or during arrest in Britain.

Excusing or downplaying British racism with comparisons to the US is a bad habit with a long history

When black Britons draw parallels between their experiences and those of African Americans, they are not suggesting that those experiences are identical. Few people would deny that in many respects life is better for non-white people in the UK than in the US. The problem is that it is not as “better” as some like to believe. Black men are stopped and searched at nine times the rate of white men. Black people make up 3% of the population of England and Wales but account for 12% of the prison population and not since 1971 have British police officers been prosecuted for the killing of a black man, and even then they were charged with the lesser crime of manslaughter and that charge was later dropped.

To say that the racism that infects parts of our police force and criminal justice system is less virulent than that which poisons the lives of 40 million African Americans is not much of a boast. Is that really the extent of our ambition – to be a somewhat less racist nation than one led by a man who describes white nationalists and members of the Ku Klux Klan as “very fine people”? Surely we who dwell in what the actor Laurence Fox recently assured us is “the most tolerant, lovely country in Europe” have higher hopes?

Excusing or downplaying British racism with comparisons to the US is a bad habit with a long history. It began in 1807, with the abolition of the slave trade and picked up steam three decades later with the end of British slavery, twin events that marked the beginning of 200 years of moral posturing and historical amnesia. The Victorian readers who rightly wept over Uncle Tom’s Cabin, for example, conveniently forgot which nation had carried his ancestors into slavery and didn’t dwell on the fact that most of the cotton produced by American slaves like him was shipped to Liverpool.

For two centuries, we have deployed American racism as a distraction. It’s as if we find it easier to recognise American forms of racism than we do our own home-grown varieties. Convenient, as pointing fingers is always more comforting than looking in the mirror.

Thursday, 4 June 2020

Genetics is not why more BAME people die of coronavirus: structural racism is

Yes, more people of black, Latin and south Asian origin are dying, but there is no genetic ‘susceptibility’ behind it writes Winston Morgan in The Guardian

Indeed, race is a social construct with no scientific basis. However, there are clear links between people’s racial groups, their socioeconomic status, what happens to them once they are infected, and the outcome of their infection. And focusing on the idea of a genetic link merely serves to distract from this.

You only have to look at how the statistics are gathered to understand how these issues are confused. Data from the UK’s Office for National Statistics that has been used to highlight the disparate death rates separates Indians from Pakistanis and Bangladeshis, and yet groups together all Africans (including black Caribbeans). This makes no sense in terms of race, ethnicity or genetics.

The data shows that those males categorised as black are more than 4.6 times more likely to die than their white counterparts from the virus. They are followed by Pakistanis/Bangladeshis (just over four times more likely to die), and then Chinese and Indians (just over 2.5 times).

Most genome-wide association studies group all south Asians. Yet, at least in the UK, Covid-19 can apparently separate Indians and Pakistanis, suggesting genetics have little to do with it. The categories used to collect government data for the pandemic are far more suited to social outcomes such as employment or education.

This problem arises even with a recent analysis that purportedly shows people from ethnic minorities are no more likely to die, once you take into account the effects of other illnesses and deprivation. The main analysis only compares whites to everybody else, masking the data for specific groups, while the headline of the newspaper article about the study refers only to black people.

Meanwhile, in the US the groups most disproportionately affected are African Americans and Hispanics/Latinos. All these groups come from very different population groups. We’ve also seen high death rates in Brazil, China and Italy, all of which have very different populations using the classical definition of race.

The idea that Covid-19 discriminates along traditional racial lines is created by these statistics and fails to adequately portray what’s really going on. These kinds of assumptions ignore the fact that there is as much genetic variation within racialised groups as there is between the whole human population.

There are some medical conditions with a higher prevalence in some racialised groups, such as sickle cell anaemia, and differences in how some groups respond to certain drugs. But these are traits linked to single genes and all transcend the traditional definitions of race. Such “monogenic” traits affect a very small subset of many populations, such as some southern Europeans and south Asians who also have a predisposition to sickle cell anaemia.

Death from Covid-19 is also linked to pre-existing conditions that appear in higher levels in black and south Asian groups, such as diabetes. The argument that this may provide a genetic underpinning is only partly supported by the limited evidence that links genetics to diabetes.

However, the ONS figures confirm that genes predisposing people to diabetes cannot be the same as those that predispose to Covid-19. Otherwise, Indians would be affected as much as Pakistanis and Bangladeshis, who belong to the same genome-wide association group.

Any genetic differences that may predispose you to diabetes are heavily influenced by environmental factors. There isn’t a “diabetes gene” linking the varying groups that are affected by Covid-19. But the prevalence of these so-called “lifestyle” diseases in racialised groups is strongly linked to social factors.

Another target that has come in for speculation is vitamin D deficiency. People with darker skin who do not get enough exposure to direct sunlight may produce less vitamin D, which is essential for many bodily functions, including the immune system. In terms of a link to susceptibility to Covid-19, this has not been proven. But very little work on this has been done and the pandemic should prompt more research on the medical consequences of vitamin D deficiency generally.

Other evidence suggests higher death rates from Covid-19 including among racialised groups might be linked to higher levels of a cell surface receptor molecule known as ACE2. But this can result from taking drugs for diabetes and hypertension, which takes us back to the point about the social causes of such diseases.

In the absence of any genetic link between racial groups and susceptibility to the virus, we are left with the reality, which seems more difficult to accept: that these groups are suffering more from how our societies are organised. There is no clear evidence that higher levels of conditions such as type-2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and weakened immune systems in disadvantaged communities are because of inherent genetic predispositions.

But there is evidence they are the result of structural racism. All these underlying problems can be directly connected to the food and exercise you have access to, the level of education, employment, housing, healthcare, economic and political power within these communities.

The evidence suggests that this coronavirus does not discriminate, but highlights existing discriminations. The continued prevalence of ideas about race today – despite the lack of any scientific basis – shows how these ideas can mutate to provide justification for the power structures that have ordered our society since the 18th century.

A TfL worker sprays antiviral solution inside a tube train. Photograph: Kirsty O’Connor/PA

From the start of the coronavirus pandemic, there has been an attempt to use science to explain the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on different groups through the prism of race. Data from the UK and the US suggests that people categorised as black, Hispanic (Latino) and south Asian are more likely to die from the disease.

The way this issue is often discussed, but also the response of some scientists, would suggest that there might be some biological reason for the higher death rates based on genetic differences between these groups and their white counterparts. But the reality is there is no evidence that the genes used to divide people into races are linked to how our immune system responds to viral infections.

There are certain genetic mutations that can be found among specific ethnic groups that can play a role in the body’s immune response. But because of the loose definition of race (primarily based on genes for skin colour) and recent population movements, these should be seen as unreliable indicators when it comes to susceptibility to viral infections.

From the start of the coronavirus pandemic, there has been an attempt to use science to explain the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on different groups through the prism of race. Data from the UK and the US suggests that people categorised as black, Hispanic (Latino) and south Asian are more likely to die from the disease.

The way this issue is often discussed, but also the response of some scientists, would suggest that there might be some biological reason for the higher death rates based on genetic differences between these groups and their white counterparts. But the reality is there is no evidence that the genes used to divide people into races are linked to how our immune system responds to viral infections.

There are certain genetic mutations that can be found among specific ethnic groups that can play a role in the body’s immune response. But because of the loose definition of race (primarily based on genes for skin colour) and recent population movements, these should be seen as unreliable indicators when it comes to susceptibility to viral infections.

Indeed, race is a social construct with no scientific basis. However, there are clear links between people’s racial groups, their socioeconomic status, what happens to them once they are infected, and the outcome of their infection. And focusing on the idea of a genetic link merely serves to distract from this.

You only have to look at how the statistics are gathered to understand how these issues are confused. Data from the UK’s Office for National Statistics that has been used to highlight the disparate death rates separates Indians from Pakistanis and Bangladeshis, and yet groups together all Africans (including black Caribbeans). This makes no sense in terms of race, ethnicity or genetics.

The data shows that those males categorised as black are more than 4.6 times more likely to die than their white counterparts from the virus. They are followed by Pakistanis/Bangladeshis (just over four times more likely to die), and then Chinese and Indians (just over 2.5 times).

Most genome-wide association studies group all south Asians. Yet, at least in the UK, Covid-19 can apparently separate Indians and Pakistanis, suggesting genetics have little to do with it. The categories used to collect government data for the pandemic are far more suited to social outcomes such as employment or education.

This problem arises even with a recent analysis that purportedly shows people from ethnic minorities are no more likely to die, once you take into account the effects of other illnesses and deprivation. The main analysis only compares whites to everybody else, masking the data for specific groups, while the headline of the newspaper article about the study refers only to black people.

Meanwhile, in the US the groups most disproportionately affected are African Americans and Hispanics/Latinos. All these groups come from very different population groups. We’ve also seen high death rates in Brazil, China and Italy, all of which have very different populations using the classical definition of race.

The idea that Covid-19 discriminates along traditional racial lines is created by these statistics and fails to adequately portray what’s really going on. These kinds of assumptions ignore the fact that there is as much genetic variation within racialised groups as there is between the whole human population.

There are some medical conditions with a higher prevalence in some racialised groups, such as sickle cell anaemia, and differences in how some groups respond to certain drugs. But these are traits linked to single genes and all transcend the traditional definitions of race. Such “monogenic” traits affect a very small subset of many populations, such as some southern Europeans and south Asians who also have a predisposition to sickle cell anaemia.

Death from Covid-19 is also linked to pre-existing conditions that appear in higher levels in black and south Asian groups, such as diabetes. The argument that this may provide a genetic underpinning is only partly supported by the limited evidence that links genetics to diabetes.

However, the ONS figures confirm that genes predisposing people to diabetes cannot be the same as those that predispose to Covid-19. Otherwise, Indians would be affected as much as Pakistanis and Bangladeshis, who belong to the same genome-wide association group.

Any genetic differences that may predispose you to diabetes are heavily influenced by environmental factors. There isn’t a “diabetes gene” linking the varying groups that are affected by Covid-19. But the prevalence of these so-called “lifestyle” diseases in racialised groups is strongly linked to social factors.

Another target that has come in for speculation is vitamin D deficiency. People with darker skin who do not get enough exposure to direct sunlight may produce less vitamin D, which is essential for many bodily functions, including the immune system. In terms of a link to susceptibility to Covid-19, this has not been proven. But very little work on this has been done and the pandemic should prompt more research on the medical consequences of vitamin D deficiency generally.

Other evidence suggests higher death rates from Covid-19 including among racialised groups might be linked to higher levels of a cell surface receptor molecule known as ACE2. But this can result from taking drugs for diabetes and hypertension, which takes us back to the point about the social causes of such diseases.

In the absence of any genetic link between racial groups and susceptibility to the virus, we are left with the reality, which seems more difficult to accept: that these groups are suffering more from how our societies are organised. There is no clear evidence that higher levels of conditions such as type-2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and weakened immune systems in disadvantaged communities are because of inherent genetic predispositions.

But there is evidence they are the result of structural racism. All these underlying problems can be directly connected to the food and exercise you have access to, the level of education, employment, housing, healthcare, economic and political power within these communities.

The evidence suggests that this coronavirus does not discriminate, but highlights existing discriminations. The continued prevalence of ideas about race today – despite the lack of any scientific basis – shows how these ideas can mutate to provide justification for the power structures that have ordered our society since the 18th century.

Sunday, 12 April 2020

NHS ‘score’ tool to decide which patients receive critical care

Doctors will use three metrics: age, frailty and underlying conditions write Peter Foster, Bethan Staton and Naomi Rovnick in The FT

Doctors coping with the coming peak of the coronavirus outbreak will have to “score” thousands of patients to decide who is suitable for intensive care treatment using a Covid-19 decision tool developed by the National Health Service.

With about 5,000 coronavirus cases presenting every day and some intensive care wards already approaching capacity, doctors will score patients on three metrics — their age, frailty and underlying conditions — according to a chart circulated to clinicians.

Patients with a combined score of more than eight points across the three categories should probably not be admitted to intensive care, according to the Covid-19 Decision Support Tool, although clinical discretion could override that decision.

The UK is set to exceed 80,000 coronavirus cases on Sunday and 10,000 deaths in hospital with government models showing the peak of the outbreak is now expected to be reached over the next two weeks, leaving the healthcare system facing arguably its toughest challenge since its inception.

The scale of the pandemic and the speed at which Covid-19 can affect patients, has forced community care workers, GPs and palliative carers to accelerate difficult conversations about death and end-of-life planning among vulnerable groups.

The NHS scoring system reveals that any patient over 70 years old will be a borderline candidate for intensive care treatment, with a patient aged 71-75 automatically scoring four points for their age and a likely three on the “frailty index”, taking their total base score to seven points.

Any additional “comorbidity”, such as dementia, or recent heart or lung disease, or high blood pressure will add one or two points to the score, tipping them into the category suitable for “ward-based care”, rather than intensive care, and a trial of non-invasive ventilation.

Although doctors and care workers stress that no patient is simply a number, the chart nonetheless codifies the process for the life-and-death choices that thousands of NHS doctors will make in the coming weeks.

A frontline NHS consultant triaging Covid-19 patients said the “game-changer” for assessment of patients with coronavirus was that there is no available treatment, meaning doctors can only provide organ support and hope the patient recovers.

“If this was a bacterial pneumonia or a bad asthma attack, then that is treatable and you might send that older patient to intensive care,” the consultant said, adding that decisions on patients were “art not science” and there would be exceptions for patients who were fit enough.

“The scoring system is just a guide; we make the judgment taking into account a lot of information about the current ‘nick’ of the patient — oxygenation, kidney function, heart rate, blood pressure — which all adds into the decision making,” he said.

But it is not just hospital doctors who must make tough decisions. GPs, hospice workers and families with vulnerable members are also involved.

Last week NHS England wrote to all GPs asking them to contact vulnerable patients to ensure that care plans and prescriptions were in place for end of life decisions, leading to many difficult conversations. These have been made harder by the need to conduct them on the phone or via Skype to observe social distancing rules.

Ruthe Isden, head of health and care at Age UK, the charity, said the need for haste had unsettled many elderly patients, who have felt under pressure to sign “Do Not Resuscitate”, or DNR, forms.

"Clinicians are trying to do the right thing and these are very important conversations to have, but there’s no justification in doing them in a blanket way,” she said. “It is such a personal conversation and it’s being approached in a very impersonal way.”

The subject of DNR notices is particularly unsettling for individuals and families who want the best care for their loved ones, but often feel the choices have not been fully explained.

The data clearly show that resuscitation often does not work for elderly patients and can often cause more suffering — including broken ribs and brain damage — while extending life only by a matter of days.

Doctors coping with the coming peak of the coronavirus outbreak will have to “score” thousands of patients to decide who is suitable for intensive care treatment using a Covid-19 decision tool developed by the National Health Service.

With about 5,000 coronavirus cases presenting every day and some intensive care wards already approaching capacity, doctors will score patients on three metrics — their age, frailty and underlying conditions — according to a chart circulated to clinicians.

Patients with a combined score of more than eight points across the three categories should probably not be admitted to intensive care, according to the Covid-19 Decision Support Tool, although clinical discretion could override that decision.

The UK is set to exceed 80,000 coronavirus cases on Sunday and 10,000 deaths in hospital with government models showing the peak of the outbreak is now expected to be reached over the next two weeks, leaving the healthcare system facing arguably its toughest challenge since its inception.

The scale of the pandemic and the speed at which Covid-19 can affect patients, has forced community care workers, GPs and palliative carers to accelerate difficult conversations about death and end-of-life planning among vulnerable groups.

The NHS scoring system reveals that any patient over 70 years old will be a borderline candidate for intensive care treatment, with a patient aged 71-75 automatically scoring four points for their age and a likely three on the “frailty index”, taking their total base score to seven points.

Any additional “comorbidity”, such as dementia, or recent heart or lung disease, or high blood pressure will add one or two points to the score, tipping them into the category suitable for “ward-based care”, rather than intensive care, and a trial of non-invasive ventilation.

Although doctors and care workers stress that no patient is simply a number, the chart nonetheless codifies the process for the life-and-death choices that thousands of NHS doctors will make in the coming weeks.

A frontline NHS consultant triaging Covid-19 patients said the “game-changer” for assessment of patients with coronavirus was that there is no available treatment, meaning doctors can only provide organ support and hope the patient recovers.

“If this was a bacterial pneumonia or a bad asthma attack, then that is treatable and you might send that older patient to intensive care,” the consultant said, adding that decisions on patients were “art not science” and there would be exceptions for patients who were fit enough.

“The scoring system is just a guide; we make the judgment taking into account a lot of information about the current ‘nick’ of the patient — oxygenation, kidney function, heart rate, blood pressure — which all adds into the decision making,” he said.

But it is not just hospital doctors who must make tough decisions. GPs, hospice workers and families with vulnerable members are also involved.

Last week NHS England wrote to all GPs asking them to contact vulnerable patients to ensure that care plans and prescriptions were in place for end of life decisions, leading to many difficult conversations. These have been made harder by the need to conduct them on the phone or via Skype to observe social distancing rules.

Ruthe Isden, head of health and care at Age UK, the charity, said the need for haste had unsettled many elderly patients, who have felt under pressure to sign “Do Not Resuscitate”, or DNR, forms.

"Clinicians are trying to do the right thing and these are very important conversations to have, but there’s no justification in doing them in a blanket way,” she said. “It is such a personal conversation and it’s being approached in a very impersonal way.”

The subject of DNR notices is particularly unsettling for individuals and families who want the best care for their loved ones, but often feel the choices have not been fully explained.

The data clearly show that resuscitation often does not work for elderly patients and can often cause more suffering — including broken ribs and brain damage — while extending life only by a matter of days.

Wednesday, 20 March 2019

Ms Z Josephs v Cambridge Centre For Sixth Form Studies: 3304286/2018

Ms Z Josephs v Cambridge Centre For Sixth Form Studies: 3304286/2018

Employment Tribunal decision.

Published 19 March 2019

- Decision date:

- 8 March 2019

- Country:

- England and Wales

- Jurisdiction code:

- Age Discrimination, Race Discrimination

Read the full decision in Ms Z Josephs v Cambridge Centre For Sixth Form Studies: 3304286/2018 - Withdrawal.

Published 19 March 2019

Wednesday, 12 December 2018

How one man’s story exposes the myths behind our migration stereotypes

Robert, a Romanian law graduate, didn’t come to the UK to undercut wages. But he ended up in insecure low-paid work writes Aditya Chakrabortty in The Guardian

The best way to defeat a crass generalisation is with specifics, and what Robert’s story tells you is it’s not the migrant worker doing the undercutting here. He even tries to get his British-born workmates to join him in a class action for what’s rightfully theirs. The real problem is instead the imbalance of power between the worker and the employer, which is happily maintained by the same politicians today who claim they want to help the “left behind”.

PMP and the 18,000 or so other employment agencies in Britain are overseen by a government inspectorate of just 11 staff. The director of labour market enforcement in the UK, David Metcalf, admits that a UK employer is likely to be inspected by his team only once every 500 years. Were I an unscrupulous boss, I would take one look at those numbers and ask myself: if I do my worst, what’s the worst that can happen?

What keeps Robert here now is those weekends with his daughter. But after 10 years in Britain he’s learned something else too, about the reality of a country that claims to welcome foreigners, even as they punish them. An economy that promises a better life to those it then sucks dry. A society that kids itself that it’s a soft touch when really, it is as cold and hard as any interminable overnight shift.

Anti-Brexit protesters in November. ‘The likes of Robert make the easiest human punchbags. You rarely see him or the millions of other EU citizens living in Britain on your TV.’ Photograph: Daniel Leal-Olivas/AFP/Getty Images

Amid all the true-blue backbench blowhards and armchair pundits who will occupy the airwaves this Brexit week, one thing is guaranteed: you won’t hear a word from Robert. Why should you? He commands neither power nor status. He has hardly any money either. And yet he is crucial to this debate, because it is people like him that Brexit Britain wants to shut out.

Robert is a migrant, under a prime minister who keeps trying and failing to impose an arbitrary cap on migrants to this country. Born in Timişoara, Romania, he now lives in a democracy that barely batted an eyelid when Nigel Farage said it was OK to be worried about Romanian neighbours. And Robert gets all the brickbats hurled at foreigners down the ages – that he’s only here to take your jobs and claim your benefits (at one and the same time, mystifyingly), to undercut your wages and give nothing back.

What’s left is a 38-year-old tearing himself apart over his broken life. ‘I’m an idiot,' he says. ‘I’ve wasted myself.'

The likes of Robert make the easiest human punchbags. You rarely see him or the millions of other EU citizens living in Britain on your TV. Nor do you hear about them from a political class forever chuntering on about the will of the people, yet too aloof from the people to know who they are or what they want, and too scared of them to engage in dialogue.

Yet Robert (he’s asked that his surname be withheld) is no caricature. It’s not just how he dotes on his daughter and has a streak of irony thicker than the coffee he serves up. It’s also how his life in Britain proves that those declaimed causes of Brexit are both too easy and too far off the mark. However sad his story, it also shows where our economy really is broken – and how it will not be fixed by kicking out migrants.

We met a few weeks ago at his flat on the outskirts of Newcastle upon Tyne. Too bare to be a home, its sole reminder of his old family life is a little girl’s bedroom, kept in unchildlike order for his daughter’s weekend visits. He and his wife split a few months ago, he says, when the family’s money ran out. What’s left now is a bank account in almost permanent overdraft and a 38-year-old man tearing himself apart over his broken life here. “I’m an idiot,” he says. “I’ve wasted myself.”

But please, spare him the migrant stereotypes. Low-skilled? Robert came to the UK in 2008 with a law degree and speaking three languages. Low aspirations? Even while grafting in restaurants and hotels, he fired off over 100 applications for a solicitor’s training contract. That yielded just one interview, in Leeds. Local firms that were happy to have him volunteer for free proved more reluctant to give him a paying job. He ended up in a part of the country that has spent most of the past 40 years trying to recover from Thatcherism’s devastation, and which is even now paying the price in cuts for the havoc wreaked 10 years ago by bankers largely based hundreds of miles away. In a country where relations between regions are as lopsided as they are between workers and bosses, the odds were stacked against him from the start.

Finally, Robert signed with a temp agency, PMP Recruitment, which in August 2012 placed him with the local Nestlé factory. And that’s where trouble really began.

He had just enrolled in the precarious workforce, which at the last count numbered just over 3.8 million workers across the UK. Never guaranteed work, he had to wait for the offer of shifts to be texted to him a few days beforehand. He did days, nights, whatever was given, and started on the minimum wage in Nestlé’s Fawdon plant – a giant place churning out Toffee Crisps and Rolos and Fruit Pastilles. It was no Willy Wonka-land.

Robert began by “spotting” – standing on a podium overlooking the Blue Riband production line and pulling out imperfect chocolate bars. Seeing the conveyor belt spool along for hours on end made him dizzy, and another recently departed worker tells me he couldn’t bear to do it for long (Nestlé says it has “rotation processes for work that is particularly repetitive”). Stubborn pride made him stick it out for 12-hour shifts. “Leave your head at home,” workmates would advise and, amid the exhaustion of shifts and raising a family, that’s what he did. But bit by bit he noticed things were wrong.

As an agency worker, he says he was doing the same tasks as Nestlé staff, but for less money. They got a pay rise, he alleges, that agency workers didn’t. He would do work classed by the company as “skilled” but instead got “unskilled” rates. His former workmate, who doesn’t wish to be named, tells me this was common practice: “If Nestlé wanted you to come in at an awkward time, they’d say, ‘We can pay you skilled rates’.” Over the years, Robert estimates that he lost out on about £26,000 of income.

Robert was in no man’s land. He was spending his days working for Nestlé but was not their direct employee – even though he gave five years of service at Fawdon. Nor did he have much to do with his recruiters at PMP, a nationwide agency. As for the plant’s trade unions, he saw them as “a waste of space”. He was trapped in an institutional vacuum. The chair of the Law Society’s employment law committee, Max Winthrop, describes such arrangements – working for one company while on the books of another for years on end – as a “fiction”. “The most generous way you can look at it is, it’s a confusing situation. The least generous is that it’s a deliberate attempt to throw sand in everyone’s eyes so we can’t see the true nature of the relationship.” Nestlé says that of its 600 staff at Fawdon, 100 are agency, all via PMP. Over the years, Robert says he saw hundreds of agency staff come and go.

When Robert raised the issue with Nestlé managers, he alleges that shifts were no longer given to him. Finally, just before last Christmas, he resigned. He then tried to get other agency workers to join him in taking Nestlé to court, but they were, he says, “too nervous”. So he launched an employment tribunal case alone and, a few weeks after we met, Nestlé settled out of court. One of the conditions of the settlement is that he cannot discuss it, but Robert knows this article will appear. Citing confidentiality, Nestlé did not want to comment directly on his case but says that, since 2014, all staff in its factories get the living wage, and “we refute any allegation that working conditions at our Fawdon factory are below standard”.

On his PMP payslips Robert also noticed that – as a result of the “recruitment travel scheme” in which the agency had enrolled him – some months he was getting less than minimum wage, a situation for which Winthrop says he “cannot find any justification”. He took PMP to court too, and a couple of months ago was awarded over £2,000 in back pay. PMP wouldn’t comment for this piece, other than to say it is appealing the verdict.

Amid all the true-blue backbench blowhards and armchair pundits who will occupy the airwaves this Brexit week, one thing is guaranteed: you won’t hear a word from Robert. Why should you? He commands neither power nor status. He has hardly any money either. And yet he is crucial to this debate, because it is people like him that Brexit Britain wants to shut out.

Robert is a migrant, under a prime minister who keeps trying and failing to impose an arbitrary cap on migrants to this country. Born in Timişoara, Romania, he now lives in a democracy that barely batted an eyelid when Nigel Farage said it was OK to be worried about Romanian neighbours. And Robert gets all the brickbats hurled at foreigners down the ages – that he’s only here to take your jobs and claim your benefits (at one and the same time, mystifyingly), to undercut your wages and give nothing back.

What’s left is a 38-year-old tearing himself apart over his broken life. ‘I’m an idiot,' he says. ‘I’ve wasted myself.'

The likes of Robert make the easiest human punchbags. You rarely see him or the millions of other EU citizens living in Britain on your TV. Nor do you hear about them from a political class forever chuntering on about the will of the people, yet too aloof from the people to know who they are or what they want, and too scared of them to engage in dialogue.

Yet Robert (he’s asked that his surname be withheld) is no caricature. It’s not just how he dotes on his daughter and has a streak of irony thicker than the coffee he serves up. It’s also how his life in Britain proves that those declaimed causes of Brexit are both too easy and too far off the mark. However sad his story, it also shows where our economy really is broken – and how it will not be fixed by kicking out migrants.

We met a few weeks ago at his flat on the outskirts of Newcastle upon Tyne. Too bare to be a home, its sole reminder of his old family life is a little girl’s bedroom, kept in unchildlike order for his daughter’s weekend visits. He and his wife split a few months ago, he says, when the family’s money ran out. What’s left now is a bank account in almost permanent overdraft and a 38-year-old man tearing himself apart over his broken life here. “I’m an idiot,” he says. “I’ve wasted myself.”

But please, spare him the migrant stereotypes. Low-skilled? Robert came to the UK in 2008 with a law degree and speaking three languages. Low aspirations? Even while grafting in restaurants and hotels, he fired off over 100 applications for a solicitor’s training contract. That yielded just one interview, in Leeds. Local firms that were happy to have him volunteer for free proved more reluctant to give him a paying job. He ended up in a part of the country that has spent most of the past 40 years trying to recover from Thatcherism’s devastation, and which is even now paying the price in cuts for the havoc wreaked 10 years ago by bankers largely based hundreds of miles away. In a country where relations between regions are as lopsided as they are between workers and bosses, the odds were stacked against him from the start.

Finally, Robert signed with a temp agency, PMP Recruitment, which in August 2012 placed him with the local Nestlé factory. And that’s where trouble really began.

He had just enrolled in the precarious workforce, which at the last count numbered just over 3.8 million workers across the UK. Never guaranteed work, he had to wait for the offer of shifts to be texted to him a few days beforehand. He did days, nights, whatever was given, and started on the minimum wage in Nestlé’s Fawdon plant – a giant place churning out Toffee Crisps and Rolos and Fruit Pastilles. It was no Willy Wonka-land.

Robert began by “spotting” – standing on a podium overlooking the Blue Riband production line and pulling out imperfect chocolate bars. Seeing the conveyor belt spool along for hours on end made him dizzy, and another recently departed worker tells me he couldn’t bear to do it for long (Nestlé says it has “rotation processes for work that is particularly repetitive”). Stubborn pride made him stick it out for 12-hour shifts. “Leave your head at home,” workmates would advise and, amid the exhaustion of shifts and raising a family, that’s what he did. But bit by bit he noticed things were wrong.

As an agency worker, he says he was doing the same tasks as Nestlé staff, but for less money. They got a pay rise, he alleges, that agency workers didn’t. He would do work classed by the company as “skilled” but instead got “unskilled” rates. His former workmate, who doesn’t wish to be named, tells me this was common practice: “If Nestlé wanted you to come in at an awkward time, they’d say, ‘We can pay you skilled rates’.” Over the years, Robert estimates that he lost out on about £26,000 of income.

Robert was in no man’s land. He was spending his days working for Nestlé but was not their direct employee – even though he gave five years of service at Fawdon. Nor did he have much to do with his recruiters at PMP, a nationwide agency. As for the plant’s trade unions, he saw them as “a waste of space”. He was trapped in an institutional vacuum. The chair of the Law Society’s employment law committee, Max Winthrop, describes such arrangements – working for one company while on the books of another for years on end – as a “fiction”. “The most generous way you can look at it is, it’s a confusing situation. The least generous is that it’s a deliberate attempt to throw sand in everyone’s eyes so we can’t see the true nature of the relationship.” Nestlé says that of its 600 staff at Fawdon, 100 are agency, all via PMP. Over the years, Robert says he saw hundreds of agency staff come and go.

When Robert raised the issue with Nestlé managers, he alleges that shifts were no longer given to him. Finally, just before last Christmas, he resigned. He then tried to get other agency workers to join him in taking Nestlé to court, but they were, he says, “too nervous”. So he launched an employment tribunal case alone and, a few weeks after we met, Nestlé settled out of court. One of the conditions of the settlement is that he cannot discuss it, but Robert knows this article will appear. Citing confidentiality, Nestlé did not want to comment directly on his case but says that, since 2014, all staff in its factories get the living wage, and “we refute any allegation that working conditions at our Fawdon factory are below standard”.

On his PMP payslips Robert also noticed that – as a result of the “recruitment travel scheme” in which the agency had enrolled him – some months he was getting less than minimum wage, a situation for which Winthrop says he “cannot find any justification”. He took PMP to court too, and a couple of months ago was awarded over £2,000 in back pay. PMP wouldn’t comment for this piece, other than to say it is appealing the verdict.

The best way to defeat a crass generalisation is with specifics, and what Robert’s story tells you is it’s not the migrant worker doing the undercutting here. He even tries to get his British-born workmates to join him in a class action for what’s rightfully theirs. The real problem is instead the imbalance of power between the worker and the employer, which is happily maintained by the same politicians today who claim they want to help the “left behind”.

PMP and the 18,000 or so other employment agencies in Britain are overseen by a government inspectorate of just 11 staff. The director of labour market enforcement in the UK, David Metcalf, admits that a UK employer is likely to be inspected by his team only once every 500 years. Were I an unscrupulous boss, I would take one look at those numbers and ask myself: if I do my worst, what’s the worst that can happen?

What keeps Robert here now is those weekends with his daughter. But after 10 years in Britain he’s learned something else too, about the reality of a country that claims to welcome foreigners, even as they punish them. An economy that promises a better life to those it then sucks dry. A society that kids itself that it’s a soft touch when really, it is as cold and hard as any interminable overnight shift.

Sunday, 11 November 2018

Monday, 22 October 2018

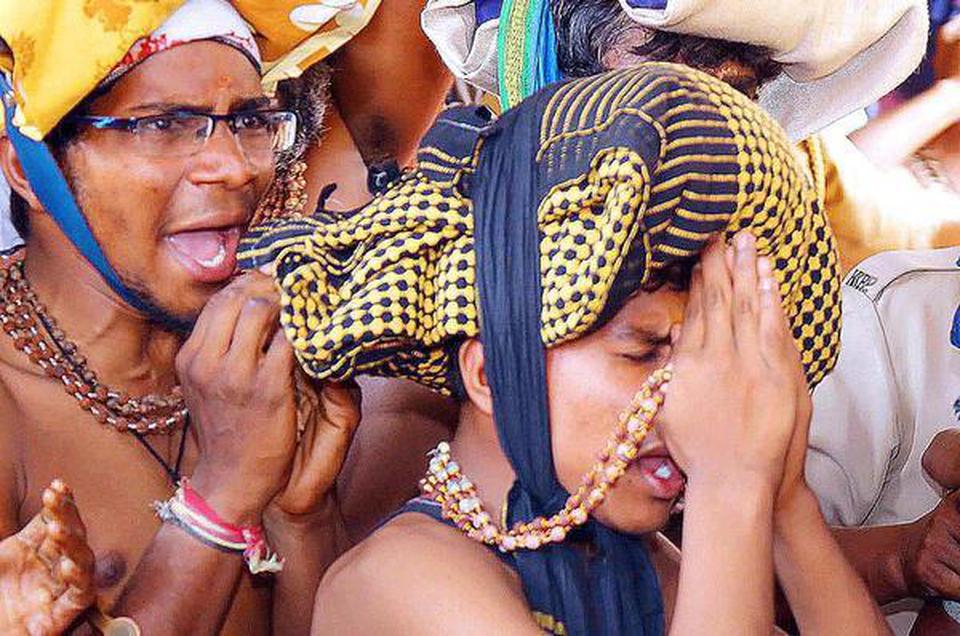

The pilgrimage’s progress

Janaki Nair in The Hindu

Shortcuts and compromises

In the 1960s, the young ‘Ayyappa’ would have been among the 15,000 or so who made that arduous journey. No longer. In the past five decades, as the numbers have burgeoned to millions, Lord Ayyappa has been witness to, and extremely tolerant of, every aspect of the pilgrimage being changed beyond recognition. Let us begin with the most important reason being cited for prohibiting women pilgrims of menstruating age: that they cannot maintain the 41-day vratham. Yet, as we know from personal knowledge, and from detailed anthropological studies of this pilgrimage, the shortcuts and compromises on that earlier observance have been many and Lord Ayyappa himself seems to have taken the changes in his stride.

Not all those who reach the foot of the 18 steps that have to be mounted for the darshan of the celibate god observe all aspects of the vratham. A corporate employee, such as one in my family, may observe the restrictions on meat, alcohol and sex, but has given up the compulsion of wearing black or being barefoot. I recall being startled when I saw ‘Ayyappas’ clad in black enjoying a smoke in the corner of the newspaper office where I once worked; I was told that it was only alcohol that was to be abjured. My surprise was greater when I saw several relatives donning the mala about a week before setting off on the pilgrimage, a serious abbreviation of the 41-day temporary asceticism. Though this has meant no diminution in the faith of those visiting the shrine, clearly the pilgrim’s progress has been adapted to the temporalities of modern life.

Lord Ayyappa has surely observed that the longer pedestrian route to his forest shrine has been shortened by the bus route. From 1,29,000 private vehicles in 2000 to 2,65,000 in 2005, not to mention the countless bus trips, this has resulted in intolerable strains on a fragile ecology. In other words, pilgrim tourism, far from being promoted by women’s entry to Sabarimala, had already reached unbearable limits.

One of the most vital practices of this pilgrimage enjoins the pilgrim to carry his own consumption basket: nothing should be available for purchase. Provisions for drinking and cleaning water apart, the sacred geography of the shrine was preserved by such restrictions on consumption. But like many large religious corporations such as Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams, the conveniences of commerce have pervaded every step of the way, with shops selling ‘Ayyapan Bags’ and other ‘ladies’ items’ that can be carried back to the women in the family. In addition to the gilding of the 18 steps, which naturally disallows the quintessential ritual of breaking coconuts, Lord Ayyappa may perhaps have been somewhat amused by the conveyor belt that carries the offerings to be counted. Those devotees who take a ‘return route’ home via Kovalam to relieve the severities of the temporary celibacy would perhaps be pardoned, even by the Lord, as much as by anthropologists who have noted such interesting accretions. And in 2016, according to the Quarterly Current Affairs, the Modi government announced plans to make Sabarimala an International Pilgrim Centre (as opposed to the State government’s request to make it a National Pilgrim Centre) for which funds “would never be a problem”.

The invention of ‘tradition’

Lest this be mistaken for a cynical recounting of the countless ways in which the pilgrimage has been ‘corrupted’, let me hasten to say that my point is far simpler. Anyone who studies the social life and history of religion will recognise that practices are constantly adapted and reshaped, as collectivities themselves are changed, adapted and refashioned to suit the constraints of cash, time or even aesthetics. For this, the historians E.J. Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger coined the term “the invention of tradition”. Who amongst us does not, albeit with a twinge of guilt, agree to the ‘token’ clipping of the hair at Tirupati in lieu of the full head shave? Who does not feel an unmatched pleasure in the piped water that gently washes the feet as we turn the corner into the main courtyard of Tirupati after hours of waiting in hot and dusty halls? And who does not feel frustrated at the not-so-gentle prod of the wooden stick by the guardian who does not allow you more than a few seconds before the deity at Guruvayur? All these belong properly to the invention of ‘tradition’ leaving no practice untouched by the conveniences of mass management.

But perhaps the most important invention of ‘tradition’ was the absolute prohibition of women of menstruating age from worship at Sabarimala under rules 3(b) framed under the Kerala Hindu Places of Public Worship (Authorisation of Entry) Act, 1965. Personal testimonies have shown that strict prohibition was not, in fact, always observed, but would such a legal specification have been necessary at all if everyone was abiding by that usage or custom from ‘time immemorial’? It is a “custom with some aberrations” as pointed out by Indira Jaisingh, citing the Devaswom Board’s earlier admission that women had freely entered the shrine before 1950 for the first rice feeding ceremonies of their children.

Elsewhere, the celibate Kumaraswami, in Sandur in Karnataka where women were strictly disallowed, has gracefully conceded space to women worshippers since 1996. “The heavens have not fallen,” Gandhi remarked in 1934 when “a small state in south India [Sandur] has opened the temple to the Harijans.” Lord Ayyappa, who has tolerated innumerable changes in the behaviour of his devotees, will surely not allow his wrath to manifest itself. He will be saddened by the hypermobilisation that surrounds the protests today, but would be far more forgiving than the men — and those women — who make, unmake and remake the rules of worship.

The rules of worship are made, unmade, and remade over time and Sabarimala is no exception

I remember seeing the ‘birth’ of Ayyappa on stage during a Kathakali performance. Following the drama of Bhasmasura’s destruction by Vishnu as Mohini, Shiva’s fear turning to gratitude, the two ‘male’ gods retreated behind the curtain drawn across the stage. The curtain trembled to the clash and roar of cymbals, drums and singing, before being lowered to reveal an image of Ayyappa. We were overawed by the performance and did not think of raising questions about the ways of the gods. I remember too, in the late 1960s, participating in the ‘kettanara’ rituals (the placing of the bundle of offerings and some items for sustenance on the pilgrim’s head before he sets off on the pilgrimage) of young cousins departing for Sabarimala on foot. The ritual involved all the women in the household. The young men were unshaven, in black, had donned the mala, and were ready to walk the long route barefoot after having observed their 41-day vrathams. I was overawed by the faith of the young ‘Ayyappa’, the women, and was too young to raise any ‘why nots’.

I remember seeing the ‘birth’ of Ayyappa on stage during a Kathakali performance. Following the drama of Bhasmasura’s destruction by Vishnu as Mohini, Shiva’s fear turning to gratitude, the two ‘male’ gods retreated behind the curtain drawn across the stage. The curtain trembled to the clash and roar of cymbals, drums and singing, before being lowered to reveal an image of Ayyappa. We were overawed by the performance and did not think of raising questions about the ways of the gods. I remember too, in the late 1960s, participating in the ‘kettanara’ rituals (the placing of the bundle of offerings and some items for sustenance on the pilgrim’s head before he sets off on the pilgrimage) of young cousins departing for Sabarimala on foot. The ritual involved all the women in the household. The young men were unshaven, in black, had donned the mala, and were ready to walk the long route barefoot after having observed their 41-day vrathams. I was overawed by the faith of the young ‘Ayyappa’, the women, and was too young to raise any ‘why nots’.

Shortcuts and compromises

In the 1960s, the young ‘Ayyappa’ would have been among the 15,000 or so who made that arduous journey. No longer. In the past five decades, as the numbers have burgeoned to millions, Lord Ayyappa has been witness to, and extremely tolerant of, every aspect of the pilgrimage being changed beyond recognition. Let us begin with the most important reason being cited for prohibiting women pilgrims of menstruating age: that they cannot maintain the 41-day vratham. Yet, as we know from personal knowledge, and from detailed anthropological studies of this pilgrimage, the shortcuts and compromises on that earlier observance have been many and Lord Ayyappa himself seems to have taken the changes in his stride.