Someone needs cancer treatment only available in Germany. Someone else is leading a 187-mile bike ride across India to pay for research into brain tumours. Top right is a team of swimmers with learning disabilities who want to attend an international competition in Sheffield; bottom left is a girl who desperately needs a bone marrow transplant. And all around are numbers that dance in front of your eyes: “£64,994 raised by 2,773 supporters … £1,044 raised by 47 supporters … £900 raised by 23 supporters.”

The online donation platform JustGiving seemingly soothes the world’s ills with a sleek, altruistic efficiency the pre-digital world could get nowhere near. Since its foundation in 2001, it claims to have raised $4.2bn (£3.3bn) for “good causes” in 164 countries.

It also styles itself as a “for-profit, for-good organisation”, but those two elements might not mesh together quite as gracefully as its founders would like. The 5% that JustGiving skims off each donation – slightly more if they are gift-aided – reportedly amounts to £20m a year. According to its accounts, one director has a salary of £152,000 plus pension contributions of £46,600. Recently there have also been questions about the provenance of two high-profile appeals it has hosted, both related to the recent Westminster attack.

Somewhat unbelievably, online donation platforms fall outside the remit of the fundraising regulator and, as reported by the Guardian this week, there are now loud calls to correct such a glaring anomaly.

According to a recent survey by the Charities Aid Foundation, only 50% of us now think charities are trustworthy. On top of hostility to government and big business, the inward-looking sensibilities crystallised in the Brexit vote might be colouring public attitudes towards the so-called third sector.

There is a sense of the same sentiments in all that noise about aid spending, now the subject of an intervention by that great charitable icon Bill Gates, who wants Theresa May to stick with the UK’s commitment to spending 0.7% of GDP on aid.

There again, even if a new public meanness partly explains some people’s scepticism, it may not explain it all. Many may well have more rational reasons: the sense of a world too beyond scrutiny, highlighted by the Kids Company saga; a reasonable suspicion that high-profile fundraising is often an easy way for governments to be let off the hook, and for wealthy people to draw attention away from their tax affairs.

But here is the strange thing. We still give almost as much to charity as we did 10 years ago, and the imperative to dig in one’s pocket has never been more ubiquitous. The shaking of tins on drizzly Saturday mornings is the stuff of the 20th century: now, charity is loud, brash and firmly built into the narcissistic, virtue-signalling world of social media. The unfortunate are helped via South American trekking and polar hikes; venturing to the other side of the world is said to be the most efficient way of helping the needy. Equally, few question the motives of the apparently selfless soul who has put up a JustGiving page or appealed for help via such platforms as GoFundMe.

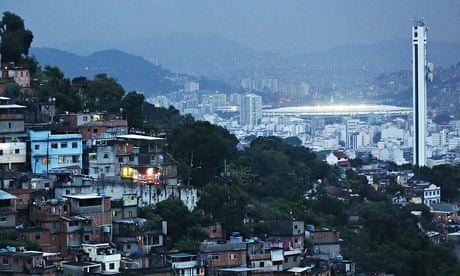

Meanwhile, charity increasingly extends to things that once came out of our taxes, with the frontier between the two disappearing fast: NHS appeals for radiotherapy equipment in Swindon, support for people with dementia in Essex, cancer treatment in London, and much more. And whereas fundraising drives for state schools were once presented as a means of funding climbing frames, school trips or specialist sports equipment, donations now increasingly pay for the fundamental things that cuts are putting in jeopardy.

According to a recent survey by the Charities Aid Foundation, only 50% of us now think charities are trustworthy. On top of hostility to government and big business, the inward-looking sensibilities crystallised in the Brexit vote might be colouring public attitudes towards the so-called third sector.

There is a sense of the same sentiments in all that noise about aid spending, now the subject of an intervention by that great charitable icon Bill Gates, who wants Theresa May to stick with the UK’s commitment to spending 0.7% of GDP on aid.

There again, even if a new public meanness partly explains some people’s scepticism, it may not explain it all. Many may well have more rational reasons: the sense of a world too beyond scrutiny, highlighted by the Kids Company saga; a reasonable suspicion that high-profile fundraising is often an easy way for governments to be let off the hook, and for wealthy people to draw attention away from their tax affairs.

But here is the strange thing. We still give almost as much to charity as we did 10 years ago, and the imperative to dig in one’s pocket has never been more ubiquitous. The shaking of tins on drizzly Saturday mornings is the stuff of the 20th century: now, charity is loud, brash and firmly built into the narcissistic, virtue-signalling world of social media. The unfortunate are helped via South American trekking and polar hikes; venturing to the other side of the world is said to be the most efficient way of helping the needy. Equally, few question the motives of the apparently selfless soul who has put up a JustGiving page or appealed for help via such platforms as GoFundMe.

Meanwhile, charity increasingly extends to things that once came out of our taxes, with the frontier between the two disappearing fast: NHS appeals for radiotherapy equipment in Swindon, support for people with dementia in Essex, cancer treatment in London, and much more. And whereas fundraising drives for state schools were once presented as a means of funding climbing frames, school trips or specialist sports equipment, donations now increasingly pay for the fundamental things that cuts are putting in jeopardy.

‘Help for Heroes is also a symbol of the fact that the state cannot adequately provide for the soldiers it puts in harm’s way.’ Photograph: Sam Frost

A primary school in Sheffield has just launched a campaign for the £100,000 it needs to fix its roof. In January, a headteacher from Brighton told the Guardian that every computer at her school was bought via fundraising, and that the proceeds from the annual school play now go on “resources to use in lessons”. In that context, if you have affluent parents and staff who know how to tap the right people, you survive. But what happens if you don’t?

Clearly, a lot of the worthy causes that benefit from sponsored walks, bake-offs and Indian bike-rides can easily be recast as examples of outrageous government negligence. There might be no better example than Help for Heroes – which nobly assists those who have “suffered injuries or illness as a result of their service to the nation”– but is also a symbol of the fact that the state cannot adequately provide for the soldiers it puts in harm’s way. Why does such a basic aspect of any advanced society require a begging bowl?

The word “normalisation” springs to mind. That said, some of us are old enough to remember the hardcore socialist values that once damned charity as a get-out for vested interests, and an offence to basic human dignity. As far as I can tell, the basic argument still stands: charity eats away at the idea of a decent life as a basic right, and turns its recipients into supplicants; not for nothing is it the favoured get-out of tyrants, tycoons and monarchs.

Scepticism about fundraising may be a sign that some of this critique lingers in the public mind; the pang of unease people feel when presented with heart-tugging appeals might be about something much deeper than the predicament of the people in the photographs.

Certain economic and cultural changes vividly denote our seemingly endless passage away from the postwar settlement into a much more Darwinian world. Trade union membership declines. Private debt soars. Public housing is consigned to history. And at every turn, what one group of people rely on is suddenly dependent on others’ generosity.

That is not to deny the sterling work charities do, or the inescapable compulsion to meet their appeals by reaching for your debit card. What bothers me is the future implied by some of the categories listed on JustGiving’s website: “education”, “international aid”, “health and medical”, and “disability”, the latter with a cutesy little icon of a wheelchair.

In the midst of an election called by a Tory vicar’s daughter in which the opposition is trying in vain to land arguments about austerity and poverty, the key question seems more relevant than ever: where is all this is taking us, and who will the bowl be passed to next?

Clearly, a lot of the worthy causes that benefit from sponsored walks, bake-offs and Indian bike-rides can easily be recast as examples of outrageous government negligence. There might be no better example than Help for Heroes – which nobly assists those who have “suffered injuries or illness as a result of their service to the nation”– but is also a symbol of the fact that the state cannot adequately provide for the soldiers it puts in harm’s way. Why does such a basic aspect of any advanced society require a begging bowl?

The word “normalisation” springs to mind. That said, some of us are old enough to remember the hardcore socialist values that once damned charity as a get-out for vested interests, and an offence to basic human dignity. As far as I can tell, the basic argument still stands: charity eats away at the idea of a decent life as a basic right, and turns its recipients into supplicants; not for nothing is it the favoured get-out of tyrants, tycoons and monarchs.

Scepticism about fundraising may be a sign that some of this critique lingers in the public mind; the pang of unease people feel when presented with heart-tugging appeals might be about something much deeper than the predicament of the people in the photographs.

Certain economic and cultural changes vividly denote our seemingly endless passage away from the postwar settlement into a much more Darwinian world. Trade union membership declines. Private debt soars. Public housing is consigned to history. And at every turn, what one group of people rely on is suddenly dependent on others’ generosity.

That is not to deny the sterling work charities do, or the inescapable compulsion to meet their appeals by reaching for your debit card. What bothers me is the future implied by some of the categories listed on JustGiving’s website: “education”, “international aid”, “health and medical”, and “disability”, the latter with a cutesy little icon of a wheelchair.

In the midst of an election called by a Tory vicar’s daughter in which the opposition is trying in vain to land arguments about austerity and poverty, the key question seems more relevant than ever: where is all this is taking us, and who will the bowl be passed to next?