'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label philanthropy. Show all posts

Showing posts with label philanthropy. Show all posts

Thursday, 3 March 2022

Saturday, 28 March 2020

Why India’s wealthy happily donate to god and govt but loathe helping needy and poor

Be it Amitabh Bachchan or Virat Kohli, India’s rich and famous are quick to lecture or follow PM Modi’s diktat. But selfless charity is missing among most Indians writes KAVEREE BAMZAI in The Print

Migrant workers in Delhi trying to get back to Uttar Pradesh amid the nationwide Covid-19 lockdown | Photo by Suraj Singh Bisht | ThePrint

Migrant workers in Delhi trying to get back to Uttar Pradesh amid the nationwide Covid-19 lockdown | Photo by Suraj Singh Bisht | ThePrint

The modern world is facing its worst crisis in coronavirus pandemic and what are Indian celebrities doing? Well, many clapped and banged pots and pans on 22 March at 5 pm following Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s call, and filmed themselves while doing so. Others are showing us how to do dishes and clean the home, participating in mock celebrity bartan-jhadu-poncha (BJP) challenges. The rest of the world is trying to help find a cure for the deadly virus or providing monetary assistance to the poor or arranging equipment for medical workers, underlining yet again the generosity gap between other countries’ and India’s elite.

Tennis star Roger Federer donates $1.02 million to support the most vulnerable families in Switzerland during the coronavirus crisis; India’s former cricket captain Sourav Ganguly gives away Rs 50 lakh worth of rice in collaboration with the West Bengal-based company Lal Baba Rice, in what is clearly a sponsored, mutual brand-building exercise. Chinese billionaire Jack Ma donates one million face masks and 500,000 coronavirus testing kits to the United States, and pledged similar support for European and African countries; Amitabh Bachchan uses social media to spread half-baked information — such as ‘flies spread coronavirus’ — and wonders if the clanging of pots, pans and thalis defeats the potency of the virus because it was Amavasya on 22 March (he later deleted the tweet).

Hollywood’s golden couple Blake Lively and Ryan Reynolds announce they will donate $1 million to Feeding America and Food Banks Canada that work for low-income families and the elderly; while Indian cricket and Bollywood’s beautiful match Virat Kohli and Anushka Sharma get into familiar lecture mode, asking everyone to “stay home and stay safe”. This follows Anushka Sharma’s earlier run-in with a ‘luxury car’ passenger where she ticked him off for violating PM Modi’s diktat of Swachh Bharat.

Where the rich are charitably poor

What makes rich and famous Indians so quick to lecture, especially on issues in congruence with government initiatives, but so loathe to help the poor desperately in need? The 2010 Giving Pledge by Warren Buffet and Bill Gates, to which five wealthy Indians are signatories, was meant to give a gigantic push to philanthropy worldwide. This was followed by India’s then minister of corporate affairs Sachin Pilot making it legally mandatory for companies to put aside charity funds for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) projects, making India the first country in the world to pass such a legislation. This year, an attempt to criminalise non-compliance was eventually softened after an uproar from corporates.

Philanthropy is up. According to Bain and Company’s annual Philanthropy Report 2020, domestic philanthropic funding has rapidly grown from approximately Rs 12,500 crore in 2010 to approximately Rs 55,000 crore in 2018. Contributions by individual philanthropists have also recorded strong growth in the past decade. In 2010, individual contributions accounted for 26 per cent of private funding, and as of 2018, individuals contribute about 60 per cent of the total private funding in India, estimated at approximately Rs 43,000 crore.

But in a prophetic warning, the report underscored the need for philanthropy ”to now consciously focus on India’s most vulnerable” and called for targeted action for the large population caught in a vicious cycle of vulnerability — precisely those worst hit by the coronavirus pandemic.

“The disadvantaged,” it said, “are unable to adapt to unpredictable situations that can push them deeper into vulnerability, such as climate change, economic risks and socio-political threats.” Even Azim Premji, who recently made news by committing 34 per cent of his company’s shares — worth $7.5 billion or Rs 52,750 crore — to his continuing cause, the public schooling system in India, has not set aside anything specific for those affected by the coronavirus. India’s second-richest man was the first Indian to sign The Giving Pledge.

Vaishali Nigam Sinha, Chief Sustainability Officer at Renew Power, started charity a few years ago to promote giving. Her experience has been less than happy. Indians, she finds, have refrained from planned giving for broader societal transformation. “Giving is individualistic and not driven via networks, which can be quite effective as we have seen in other parts of the world like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. And in India, giving is usually done to get something back – to god for prosperity, to religious affiliations for advocacy of these platforms, and to government for business returns. Wealthy Indians need to learn to give in a planned way for greater social impact and transformation,” she says.

Little surprise then that India was ranked 124 in World Giving Index 2018 — and placed 82 in the 10th edition of the index compiled by Charities Aid Foundation looking at the data for 128 countries over the 10-year period.

All of us are in the same boat

But it’s not about celebrities or wealthy Indians alone. We are all in it together. Special planes are sent to bring back Indians stuck abroad due to the pandemic, but labourers and daily wage workers are left to walk hundreds of kilometres to reach their villages. Doctors treating coronavirus patients will be applauded but not allowed to enter their homes.

JNU sociologist Maitrayee Chaudhuri calls it a potent mix of selfishness, self care and entitlement. ”We have a complete disregard for people on the margins and on whose labour we sit. It is all about us and our safety,” she says. This communal selfishness is very different from the churning in the 19th and early 20th century, which led to enormous social reform movements. The slow and meticulous destruction of ‘secularism’, ‘socialism’ and ‘liberalism’ has helped. As has the rise of neoliberal ‘individual self centredness’. “Not to talk about smartphone dumbness,” she adds. There is an absence of empathy everywhere, filled instead with the noise of thalis being banged and bells being rung to show symbolic gratitude to those who serve us.

The examples of those who are giving are few and far in between. There is comedian Kapil Sharma, who is giving Rs 50 lakh to the Prime Minister’s Relief Fund and southern superstars Pawan Kalyan, Ram Charan and Rajinikanth. But in general, our stars have chosen to share very little. Former cricket captain M.S. Dhoni, for instance, has been reported to have donated Rs 1 lakh to a charity trust in Pune, which led to some criticism and a counter from his wife Sakshi, even though it wasn’t immediately clear which incident she was alluding to.

India Inc hasn’t fared much better either. When PM Modi asked everyone to show their support for health workers fighting coronavirus by applauding them, one of the country’s most proactive industrialists was among the first to tweet his support, and also one of the first to be trolled for it. He quickly responded by offering to manufacture ventilators, among other things. Reliance is reportedly donating a hospital for coronavirus patients, weeks after Isha Ambani had hosted a Holi party on 7 March — when the number of coronavirus cases had rapidly begun to rise. Her mother, after all, is the queen of giving, contributing to an array of eclectic causes, and has been honoured for it by getting elected to the board of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2019 or by becoming the first Indian woman in 2016 to be elected to the International Olympic Committee for supporting the sporting dreams of seven million Indian children.

But for India’s corporate class, it took a nudge from the Principal Scientific Adviser K. Vijay Raghavan to remind them that healthcare and preventive healthcare are covered under Schedule VII of the Companies Act: “Hence supporting any project or programme for preventing or controlling or managing COVID19 is legitimate CSR (CSR) expenditure.” He also quickly got an office memorandum issued by the Ministry of Corporate Affairs a day later.

Elites’ capitalist worldview

Is there a kindness deficit in India’s business elite as well, which mirrors the lack of empathy of the country’s middle class? Business writer and bestselling author Tamal Bandyopadhyay says there are exceptions but culturally, the Indian business community is not exactly fond of opening up its purse on its own unless there is a compulsion. “Even when the companies are compelled, they find ways to evade it. We all know how many of them handle their CSR activities through creation of trusts. When it comes to buying electoral bonds, the story is different.

“Similarly, some of them get excited and rush to do certain things to express solidarity with the government in power. For instance, when the push is on digitalisation, there are takers for adopting towns for digitalisation in constituencies which matter. Essentially, most of them don’t believe in doing things no strings attached. Of course, there are people who believe in doing things quietly but they are exceptions,” he says.

In Western nations such as the US, philanthropy has deeper roots, with the practice essentially starting through donations to religious organisations. By the late 19th century, there was a rise of secular philanthropists such as Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, which Stanford professor Rob Reich has noted as being controversial and one way of cleansing one’s hands of the dirty money.

In his book Just Giving: Why Philanthropy is Failing Democracy and How It Can Do Better (2018), he has noted: “Big Philanthropy is definitionally a plutocratic voice in our democracy, an exercise of power by the wealthy that is unaccountable, non-transparent, donor-directed, perpetual, and tax-subsidised.”

A similar critique has come from Anand Giridharadas, whose Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World makes the argument that the global financial elite has reinterpreted Andrew Carnegie’s view that it’s good for society for capitalists to give something back to create a new formula: It’s good for business to do so when the time is right, but not otherwise. According to Reich, philanthropy works when it is able to find a gap between what governments do and what the market wants.

Few people exemplify this better than Bill Gates, who has for long donated to the cause of global healthcare. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has already contributed $100 million to contain the virus, which he declared a pandemic even before the World Health Organisation did. The Foundation’s newsletter The Optimist is also performing a key role in spreading critical information about the Covid-19 pandemic and dispelling myths.

Migrant workers in Delhi trying to get back to Uttar Pradesh amid the nationwide Covid-19 lockdown | Photo by Suraj Singh Bisht | ThePrint

Migrant workers in Delhi trying to get back to Uttar Pradesh amid the nationwide Covid-19 lockdown | Photo by Suraj Singh Bisht | ThePrintThe modern world is facing its worst crisis in coronavirus pandemic and what are Indian celebrities doing? Well, many clapped and banged pots and pans on 22 March at 5 pm following Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s call, and filmed themselves while doing so. Others are showing us how to do dishes and clean the home, participating in mock celebrity bartan-jhadu-poncha (BJP) challenges. The rest of the world is trying to help find a cure for the deadly virus or providing monetary assistance to the poor or arranging equipment for medical workers, underlining yet again the generosity gap between other countries’ and India’s elite.

Tennis star Roger Federer donates $1.02 million to support the most vulnerable families in Switzerland during the coronavirus crisis; India’s former cricket captain Sourav Ganguly gives away Rs 50 lakh worth of rice in collaboration with the West Bengal-based company Lal Baba Rice, in what is clearly a sponsored, mutual brand-building exercise. Chinese billionaire Jack Ma donates one million face masks and 500,000 coronavirus testing kits to the United States, and pledged similar support for European and African countries; Amitabh Bachchan uses social media to spread half-baked information — such as ‘flies spread coronavirus’ — and wonders if the clanging of pots, pans and thalis defeats the potency of the virus because it was Amavasya on 22 March (he later deleted the tweet).

Hollywood’s golden couple Blake Lively and Ryan Reynolds announce they will donate $1 million to Feeding America and Food Banks Canada that work for low-income families and the elderly; while Indian cricket and Bollywood’s beautiful match Virat Kohli and Anushka Sharma get into familiar lecture mode, asking everyone to “stay home and stay safe”. This follows Anushka Sharma’s earlier run-in with a ‘luxury car’ passenger where she ticked him off for violating PM Modi’s diktat of Swachh Bharat.

Where the rich are charitably poor

What makes rich and famous Indians so quick to lecture, especially on issues in congruence with government initiatives, but so loathe to help the poor desperately in need? The 2010 Giving Pledge by Warren Buffet and Bill Gates, to which five wealthy Indians are signatories, was meant to give a gigantic push to philanthropy worldwide. This was followed by India’s then minister of corporate affairs Sachin Pilot making it legally mandatory for companies to put aside charity funds for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) projects, making India the first country in the world to pass such a legislation. This year, an attempt to criminalise non-compliance was eventually softened after an uproar from corporates.

Philanthropy is up. According to Bain and Company’s annual Philanthropy Report 2020, domestic philanthropic funding has rapidly grown from approximately Rs 12,500 crore in 2010 to approximately Rs 55,000 crore in 2018. Contributions by individual philanthropists have also recorded strong growth in the past decade. In 2010, individual contributions accounted for 26 per cent of private funding, and as of 2018, individuals contribute about 60 per cent of the total private funding in India, estimated at approximately Rs 43,000 crore.

But in a prophetic warning, the report underscored the need for philanthropy ”to now consciously focus on India’s most vulnerable” and called for targeted action for the large population caught in a vicious cycle of vulnerability — precisely those worst hit by the coronavirus pandemic.

“The disadvantaged,” it said, “are unable to adapt to unpredictable situations that can push them deeper into vulnerability, such as climate change, economic risks and socio-political threats.” Even Azim Premji, who recently made news by committing 34 per cent of his company’s shares — worth $7.5 billion or Rs 52,750 crore — to his continuing cause, the public schooling system in India, has not set aside anything specific for those affected by the coronavirus. India’s second-richest man was the first Indian to sign The Giving Pledge.

Vaishali Nigam Sinha, Chief Sustainability Officer at Renew Power, started charity a few years ago to promote giving. Her experience has been less than happy. Indians, she finds, have refrained from planned giving for broader societal transformation. “Giving is individualistic and not driven via networks, which can be quite effective as we have seen in other parts of the world like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. And in India, giving is usually done to get something back – to god for prosperity, to religious affiliations for advocacy of these platforms, and to government for business returns. Wealthy Indians need to learn to give in a planned way for greater social impact and transformation,” she says.

Little surprise then that India was ranked 124 in World Giving Index 2018 — and placed 82 in the 10th edition of the index compiled by Charities Aid Foundation looking at the data for 128 countries over the 10-year period.

All of us are in the same boat

But it’s not about celebrities or wealthy Indians alone. We are all in it together. Special planes are sent to bring back Indians stuck abroad due to the pandemic, but labourers and daily wage workers are left to walk hundreds of kilometres to reach their villages. Doctors treating coronavirus patients will be applauded but not allowed to enter their homes.

JNU sociologist Maitrayee Chaudhuri calls it a potent mix of selfishness, self care and entitlement. ”We have a complete disregard for people on the margins and on whose labour we sit. It is all about us and our safety,” she says. This communal selfishness is very different from the churning in the 19th and early 20th century, which led to enormous social reform movements. The slow and meticulous destruction of ‘secularism’, ‘socialism’ and ‘liberalism’ has helped. As has the rise of neoliberal ‘individual self centredness’. “Not to talk about smartphone dumbness,” she adds. There is an absence of empathy everywhere, filled instead with the noise of thalis being banged and bells being rung to show symbolic gratitude to those who serve us.

The examples of those who are giving are few and far in between. There is comedian Kapil Sharma, who is giving Rs 50 lakh to the Prime Minister’s Relief Fund and southern superstars Pawan Kalyan, Ram Charan and Rajinikanth. But in general, our stars have chosen to share very little. Former cricket captain M.S. Dhoni, for instance, has been reported to have donated Rs 1 lakh to a charity trust in Pune, which led to some criticism and a counter from his wife Sakshi, even though it wasn’t immediately clear which incident she was alluding to.

India Inc hasn’t fared much better either. When PM Modi asked everyone to show their support for health workers fighting coronavirus by applauding them, one of the country’s most proactive industrialists was among the first to tweet his support, and also one of the first to be trolled for it. He quickly responded by offering to manufacture ventilators, among other things. Reliance is reportedly donating a hospital for coronavirus patients, weeks after Isha Ambani had hosted a Holi party on 7 March — when the number of coronavirus cases had rapidly begun to rise. Her mother, after all, is the queen of giving, contributing to an array of eclectic causes, and has been honoured for it by getting elected to the board of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2019 or by becoming the first Indian woman in 2016 to be elected to the International Olympic Committee for supporting the sporting dreams of seven million Indian children.

But for India’s corporate class, it took a nudge from the Principal Scientific Adviser K. Vijay Raghavan to remind them that healthcare and preventive healthcare are covered under Schedule VII of the Companies Act: “Hence supporting any project or programme for preventing or controlling or managing COVID19 is legitimate CSR (CSR) expenditure.” He also quickly got an office memorandum issued by the Ministry of Corporate Affairs a day later.

Elites’ capitalist worldview

Is there a kindness deficit in India’s business elite as well, which mirrors the lack of empathy of the country’s middle class? Business writer and bestselling author Tamal Bandyopadhyay says there are exceptions but culturally, the Indian business community is not exactly fond of opening up its purse on its own unless there is a compulsion. “Even when the companies are compelled, they find ways to evade it. We all know how many of them handle their CSR activities through creation of trusts. When it comes to buying electoral bonds, the story is different.

“Similarly, some of them get excited and rush to do certain things to express solidarity with the government in power. For instance, when the push is on digitalisation, there are takers for adopting towns for digitalisation in constituencies which matter. Essentially, most of them don’t believe in doing things no strings attached. Of course, there are people who believe in doing things quietly but they are exceptions,” he says.

In Western nations such as the US, philanthropy has deeper roots, with the practice essentially starting through donations to religious organisations. By the late 19th century, there was a rise of secular philanthropists such as Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, which Stanford professor Rob Reich has noted as being controversial and one way of cleansing one’s hands of the dirty money.

In his book Just Giving: Why Philanthropy is Failing Democracy and How It Can Do Better (2018), he has noted: “Big Philanthropy is definitionally a plutocratic voice in our democracy, an exercise of power by the wealthy that is unaccountable, non-transparent, donor-directed, perpetual, and tax-subsidised.”

A similar critique has come from Anand Giridharadas, whose Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World makes the argument that the global financial elite has reinterpreted Andrew Carnegie’s view that it’s good for society for capitalists to give something back to create a new formula: It’s good for business to do so when the time is right, but not otherwise. According to Reich, philanthropy works when it is able to find a gap between what governments do and what the market wants.

Few people exemplify this better than Bill Gates, who has for long donated to the cause of global healthcare. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has already contributed $100 million to contain the virus, which he declared a pandemic even before the World Health Organisation did. The Foundation’s newsletter The Optimist is also performing a key role in spreading critical information about the Covid-19 pandemic and dispelling myths.

Indian philanthropy isn’t secular

In India, the twain of religious giving and secular funding has not met. Management expert Nirmalya Kumar calls it a sensitive subject and says it is related to the philosophical concept underlying Indian religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism and Sikhism that believe in reincarnation. “Our soul starts life again in a different physical form based on the karma of previous lives. As such, as has been sometimes articulated to me, the lack of charity is an unwillingness to interfere with the consequences that God has determined appropriate. Who am I to come in between the person and their God?”

But the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) is traditionally known for engaging in social seva (not just swayam seva , or self service), evidenced by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s decision to feed five crore people during the 21-day lockdown. Sikhism has a well-developed tradition of Guru ka langar, and it was on full display at Shaheen Bagh when ordinary Sikhs served food to people protesting against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the National Register of Citizens (NRC).

Some business families also do philanthropic work, among them the Nilekanis, the Murtys and the older Bharatrams (their founder Lala Shri Ram founded Delhi Cloth Mills and set up several educational institutes like Shri Ram College of Commerce and Lady Shri Ram College). Radhika Bharatram, joint vice chairperson, The Shri Ram Schools, recalls growing up in a middle class, progressive home where her sister and she were encouraged to volunteer at the Cheshire Home and Mother Teresa Home. Marriage, she says, brought her into a home where making contributions to society was in the family’s DNA and she is now involved as a volunteer with organisations such as Delhi Crafts Council, Blind Relief Association, SRF Foundation, the CII Foundation Woman Exemplar Programme, and Cancer Awareness Prevention and Early Detection. What drives her is empathy: When “you come from a position of privilege, there is joy in making a difference to someone else’s life”. She says it motivates her when the purpose is greater than the individual.

Unfortunately, the middle class and the elites have tended to keep self interest above public interest. In the new world after the coronavirus pandemic, this is one attitude it must change.

In India, the twain of religious giving and secular funding has not met. Management expert Nirmalya Kumar calls it a sensitive subject and says it is related to the philosophical concept underlying Indian religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism and Sikhism that believe in reincarnation. “Our soul starts life again in a different physical form based on the karma of previous lives. As such, as has been sometimes articulated to me, the lack of charity is an unwillingness to interfere with the consequences that God has determined appropriate. Who am I to come in between the person and their God?”

But the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) is traditionally known for engaging in social seva (not just swayam seva , or self service), evidenced by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s decision to feed five crore people during the 21-day lockdown. Sikhism has a well-developed tradition of Guru ka langar, and it was on full display at Shaheen Bagh when ordinary Sikhs served food to people protesting against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the National Register of Citizens (NRC).

Some business families also do philanthropic work, among them the Nilekanis, the Murtys and the older Bharatrams (their founder Lala Shri Ram founded Delhi Cloth Mills and set up several educational institutes like Shri Ram College of Commerce and Lady Shri Ram College). Radhika Bharatram, joint vice chairperson, The Shri Ram Schools, recalls growing up in a middle class, progressive home where her sister and she were encouraged to volunteer at the Cheshire Home and Mother Teresa Home. Marriage, she says, brought her into a home where making contributions to society was in the family’s DNA and she is now involved as a volunteer with organisations such as Delhi Crafts Council, Blind Relief Association, SRF Foundation, the CII Foundation Woman Exemplar Programme, and Cancer Awareness Prevention and Early Detection. What drives her is empathy: When “you come from a position of privilege, there is joy in making a difference to someone else’s life”. She says it motivates her when the purpose is greater than the individual.

Unfortunately, the middle class and the elites have tended to keep self interest above public interest. In the new world after the coronavirus pandemic, this is one attitude it must change.

Dickens and Orwell — the choice for capitalism

When this is all over, there is likely to be a new social contract. Which way will we go? asks JANAN GANESH in The FT

This year is the 70th anniversary of George Orwell’s death and the 150th of Charles Dickens’s. Never spellbound by either (“The man can’t write worth a damn,” said the young Martin Amis, after one page of 1984), I was inclined to sit out all the commemorative rereading. And I did. But then the crisis of the day took me back to what one man wrote about the other.

More on that in a minute. First, you will notice the pandemic is putting large corporations through a sort of moral invigilation. Ones that rejig their factories to make hand sanitiser (LVMH) or donate their knowhow (IBM) are hailed. Ones that behave like skinflints (JD Wetherspoon, Britannia Hotels) are tarred and feathered.

Companies have to weigh how much discretionary help to give without flunking their narrow duty to survive and profit.

This is the stuff of Stakeholder Capitalism or Corporate Social Responsibility.The topic has been in the air all of my career. It has been given new urgency by events. It is the subject of much FT treatment.

And Orwell, I suspect, would see through it like glass.

In a 1940 essay (how spoilt we are for round-number anniversaries) he politely explodes the idea of Dickens as a radical, or even as a social reformer. His case is that, for Dickens, nothing is wrong with the world that cannot be fixed through individual conscience.

If only Murdstone were kinder to David Copperfield. If only all bosses were as nice as Fezziwig. That no one should have such awesome power over others in the first place goes unsaid by Dickens, and presumably unthought. And so his worldview, says Orwell, is “almost exclusively moral”.

Dickens wants a “change of spirit rather than a change of structure”. He has no sense that a free market is “wrong as a system”. The French Revolution could have been averted had the Second Estate just “turned over a new leaf, like Scrooge”.

And so we have “that recurrent Dickens figure, the Good Rich Man”, whose arbitrary might is used to help out the odd grateful urchin or debtor. What we do not have is the Good Trade Unionist pushing for structural change. What we do not have is the Good Finance Minister redistributing wealth. There is something feudal about Dickens. The rich man in his castle should be nicer to the poor man at his gate, but each is in his rightful station.

You need not share Orwell’s ascetic socialism (I write this next to a 2010 Meursault) to see his point. And to see that it applies just as much to today’s economy.

Some companies are open to any and all options to serve the general good — except higher taxes and regulation. “I feel like I’m at a firefighters’ conference,” said the writer Rutger Bregman, at a Davos event about inequality that did not mention tax. “And no one is allowed to speak about water.”

What Orwell would hate about Stakeholder Capitalism is not just that it might achieve patchier results than the universal state. It is not even that it accords the powerful yet more power — at times, as we are seeing, over life and death. Under-resourced governments counting on private whim for basic things: it is a spectacle that should both warm the heart and utterly chill it.

No, what Orwell would resent, I think, is the unearned smugness. The halo of “conscience”, when more systemic answers are available via government. The halo that Dickens still wears. You can see it in the world of philanthropy summits and impact investment funds.

The double-anniversary of England’s most famous writers since Shakespeare meant little to me until the virus broke. All of a sudden, they serve as a neat contrast of worldviews. Dickens would look at the crisis and shame the corporates who fail to tap into their inner Fezziwig. Orwell would wonder how on earth it is left to their caprice in the first place.

The difference matters because, when all this is over, there is likely to be a new social contract. The mystery is whether it will be more Dickensian (in the best sense) or Orwellian (also in the best sense). That is, will it pressure the rich to give more to the commons or will it absolutely oblige them?

This year is the 70th anniversary of George Orwell’s death and the 150th of Charles Dickens’s. Never spellbound by either (“The man can’t write worth a damn,” said the young Martin Amis, after one page of 1984), I was inclined to sit out all the commemorative rereading. And I did. But then the crisis of the day took me back to what one man wrote about the other.

More on that in a minute. First, you will notice the pandemic is putting large corporations through a sort of moral invigilation. Ones that rejig their factories to make hand sanitiser (LVMH) or donate their knowhow (IBM) are hailed. Ones that behave like skinflints (JD Wetherspoon, Britannia Hotels) are tarred and feathered.

Companies have to weigh how much discretionary help to give without flunking their narrow duty to survive and profit.

This is the stuff of Stakeholder Capitalism or Corporate Social Responsibility.The topic has been in the air all of my career. It has been given new urgency by events. It is the subject of much FT treatment.

And Orwell, I suspect, would see through it like glass.

In a 1940 essay (how spoilt we are for round-number anniversaries) he politely explodes the idea of Dickens as a radical, or even as a social reformer. His case is that, for Dickens, nothing is wrong with the world that cannot be fixed through individual conscience.

If only Murdstone were kinder to David Copperfield. If only all bosses were as nice as Fezziwig. That no one should have such awesome power over others in the first place goes unsaid by Dickens, and presumably unthought. And so his worldview, says Orwell, is “almost exclusively moral”.

Dickens wants a “change of spirit rather than a change of structure”. He has no sense that a free market is “wrong as a system”. The French Revolution could have been averted had the Second Estate just “turned over a new leaf, like Scrooge”.

And so we have “that recurrent Dickens figure, the Good Rich Man”, whose arbitrary might is used to help out the odd grateful urchin or debtor. What we do not have is the Good Trade Unionist pushing for structural change. What we do not have is the Good Finance Minister redistributing wealth. There is something feudal about Dickens. The rich man in his castle should be nicer to the poor man at his gate, but each is in his rightful station.

You need not share Orwell’s ascetic socialism (I write this next to a 2010 Meursault) to see his point. And to see that it applies just as much to today’s economy.

Some companies are open to any and all options to serve the general good — except higher taxes and regulation. “I feel like I’m at a firefighters’ conference,” said the writer Rutger Bregman, at a Davos event about inequality that did not mention tax. “And no one is allowed to speak about water.”

What Orwell would hate about Stakeholder Capitalism is not just that it might achieve patchier results than the universal state. It is not even that it accords the powerful yet more power — at times, as we are seeing, over life and death. Under-resourced governments counting on private whim for basic things: it is a spectacle that should both warm the heart and utterly chill it.

No, what Orwell would resent, I think, is the unearned smugness. The halo of “conscience”, when more systemic answers are available via government. The halo that Dickens still wears. You can see it in the world of philanthropy summits and impact investment funds.

The double-anniversary of England’s most famous writers since Shakespeare meant little to me until the virus broke. All of a sudden, they serve as a neat contrast of worldviews. Dickens would look at the crisis and shame the corporates who fail to tap into their inner Fezziwig. Orwell would wonder how on earth it is left to their caprice in the first place.

The difference matters because, when all this is over, there is likely to be a new social contract. The mystery is whether it will be more Dickensian (in the best sense) or Orwellian (also in the best sense). That is, will it pressure the rich to give more to the commons or will it absolutely oblige them?

Friday, 26 October 2018

We don’t want billionaires’ charity. We want them to pay their taxes

Owen Jones in The Guardian

Charity is a cold, grey loveless thing. If a rich man wants to help the poor, he should pay his taxes gladly, not dole out money at a whim.” It is a phrase commonly ascribed to Clement Attlee – the credit actually belongs to his biographer, Francis Beckett – but it elegantly sums up the case for progressive taxation. According to a report by the Swiss bank UBS, last year billionaires made more money than any other point in the history of human civilisation. Their wealth jumped by a fifth – a staggering $8.9tn – and 179 new billionaires joined an exclusive cabal of 2,158. Some have signed up to Giving Pledge, committing to leave half their wealth to charity. While the richest man on earth, Jeff Bezos – who has $146bn to his name – has not, he has committed £2bn to tackling homelessness and improving education.

Who can begrudge the generosity of the wealthy, you might say. Wherever you stand on the concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a tiny global elite, surely such charity should be applauded? But philanthropy is a dangerous substitution for progressive taxation. Consider Bono, a man who gained a reputation for ceaselessly campaigning for the world’s neediest. Except his band, U2, moved their tax affairs from Ireland to the Netherlandsin 2006 in order to avoid tax. Bono himself appeared in the Paradise Papers – a huge set of documents exposing offshore investments by the wealthy – after he invested in a company based in Malta that bought a Lithuanian firm. This behaviour is legal: Bono himself said of U2’s affairs it was “just some smart people we have … trying to be sensible about the way we’re taxed”.

And he’s right: rich people and major corporations have the means to legally avoid tax. It’s estimated that global losses from multinational corporations shifting their profits are about $500bn a year, while cash stashed in tax havens is worth at least 10% of the world’s economy. It is the world’s poorest who suffer the consequences. Philanthropy, then, is a means of making the uber rich look generous, while they save far more money through exploiting loopholes and using tax havens.

The trouble with charitable billionaires

There’s another issue, too. The decision on how philanthropic money is spent is made on the whims and personal interests of the wealthy, rather than what is best. In the US, for example, only 12% of philanthropic money went to human services: it was more likely be spent on arts and higher education. Those choosing where the money goes are often highly unrepresentative of the broader population, and thus more likely to be out of touch with their needs. In the US, 85% of charitable foundation board members are white, and just 7% are African Americans. Money raised by progressive taxation, on the other hand, is spent by democratically accountable governments that have to justify their priorities, which are far more likely to relate to social need.

What is striking is that even as the rich get richer, they are spending less on charity, while the poor give a higher percentage of their income to good causes. That the world’s eight richest people have as much wealth as the poorest half of humanity is a damning indictment of our entire social order. The answer to that is not self-serving philanthropy, which makes a wealthy elite determined to put vast fortunes out of reach of the authorities look good. We need global tax justice, not charitable scraps dictated by the fancies of the elite.

Charity is a cold, grey loveless thing. If a rich man wants to help the poor, he should pay his taxes gladly, not dole out money at a whim.” It is a phrase commonly ascribed to Clement Attlee – the credit actually belongs to his biographer, Francis Beckett – but it elegantly sums up the case for progressive taxation. According to a report by the Swiss bank UBS, last year billionaires made more money than any other point in the history of human civilisation. Their wealth jumped by a fifth – a staggering $8.9tn – and 179 new billionaires joined an exclusive cabal of 2,158. Some have signed up to Giving Pledge, committing to leave half their wealth to charity. While the richest man on earth, Jeff Bezos – who has $146bn to his name – has not, he has committed £2bn to tackling homelessness and improving education.

Who can begrudge the generosity of the wealthy, you might say. Wherever you stand on the concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a tiny global elite, surely such charity should be applauded? But philanthropy is a dangerous substitution for progressive taxation. Consider Bono, a man who gained a reputation for ceaselessly campaigning for the world’s neediest. Except his band, U2, moved their tax affairs from Ireland to the Netherlandsin 2006 in order to avoid tax. Bono himself appeared in the Paradise Papers – a huge set of documents exposing offshore investments by the wealthy – after he invested in a company based in Malta that bought a Lithuanian firm. This behaviour is legal: Bono himself said of U2’s affairs it was “just some smart people we have … trying to be sensible about the way we’re taxed”.

And he’s right: rich people and major corporations have the means to legally avoid tax. It’s estimated that global losses from multinational corporations shifting their profits are about $500bn a year, while cash stashed in tax havens is worth at least 10% of the world’s economy. It is the world’s poorest who suffer the consequences. Philanthropy, then, is a means of making the uber rich look generous, while they save far more money through exploiting loopholes and using tax havens.

The trouble with charitable billionaires

There’s another issue, too. The decision on how philanthropic money is spent is made on the whims and personal interests of the wealthy, rather than what is best. In the US, for example, only 12% of philanthropic money went to human services: it was more likely be spent on arts and higher education. Those choosing where the money goes are often highly unrepresentative of the broader population, and thus more likely to be out of touch with their needs. In the US, 85% of charitable foundation board members are white, and just 7% are African Americans. Money raised by progressive taxation, on the other hand, is spent by democratically accountable governments that have to justify their priorities, which are far more likely to relate to social need.

What is striking is that even as the rich get richer, they are spending less on charity, while the poor give a higher percentage of their income to good causes. That the world’s eight richest people have as much wealth as the poorest half of humanity is a damning indictment of our entire social order. The answer to that is not self-serving philanthropy, which makes a wealthy elite determined to put vast fortunes out of reach of the authorities look good. We need global tax justice, not charitable scraps dictated by the fancies of the elite.

Friday, 25 May 2018

The trouble with charitable billionaires

More and more wealthy CEOs are pledging to give away parts of their fortunes – often to help fix problems their companies caused. Some call this ‘philanthrocapitalism’, but is it just corporate hypocrisy? By Carl Rhodes and Peter Bloom in The Guardian

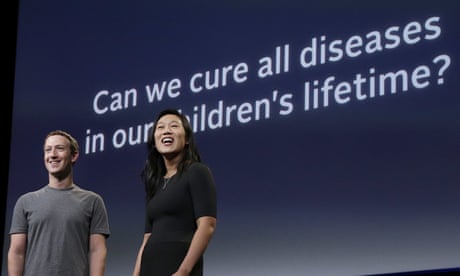

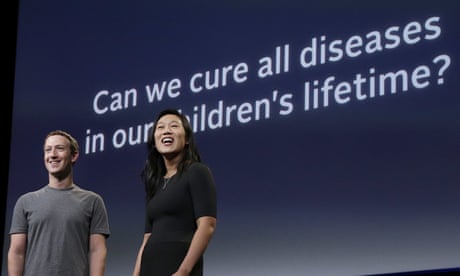

In February 2017, Facebook’s founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg was in the headlines for his charitable activities. The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, founded by the tech billionaire and his wife, Priscilla Chan, handed out over $3m in grants to aid the housing crisis in the Silicon Valley area. David Plouffe, the Initiative’s president of policy and advocacy, stated that the grants were intended to “support those working to help families in immediate crisis while supporting research into new ideas to find a long-term solution – a two-step strategy that will guide much of our policy and advocacy work moving forward”.

This is but one small part of Zuckerberg’s charity empire. The Initiative has committed billions of dollars to philanthropic projects designed to address social problems, with a special focus on solutions driven by science, medical research and education. This all took off in December 2015, when Zuckerberg and Chan wrote and published a letter to their new baby Max. The letter made a commitment that over the course of their lives they would donate 99% of their shares in Facebook (at the time valued at $45bn) to the “mission” of “advancing human potential and promoting equality”.

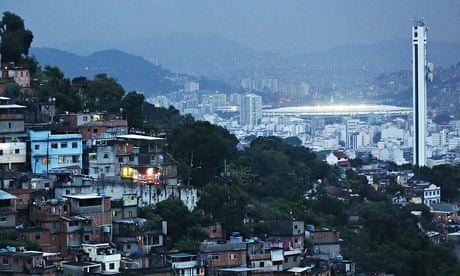

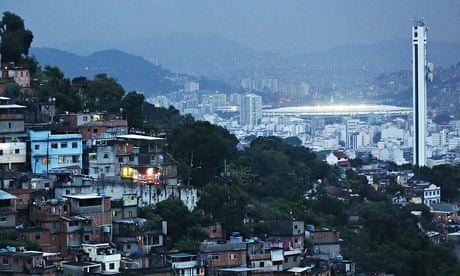

The housing intervention is of course much closer to home, dealing with issues literally at the door of Facebook’s Menlo Park head office. This is an area where median house prices almost doubled to around $2m in the five years between 2012 and 2017.

More generally, San Francisco is a city with massive income inequality, and the reputation of having the most expensive housing in the US. Chan Zuckerberg’s intervention was clearly designed to offset social and economic problems caused by rents and house prices having skyrocketed to such a level that even tech workers on six-figure salaries find it hard to get by. For those on more modest incomes, supporting themselves, let alone a family, is nigh-on impossible.

Ironically, the boom in the tech industry in this region – a boom Facebook has been at the forefront of – has been a major contributor to the crisis. As Peter Cohen from the Council of Community Housing Organizations explained it: “When you’re dealing with this total concentration of wealth and this absurd slosh of real-estate money, you’re not dealing with housing that’s serving a growing population. You’re dealing with housing as a real-estate commodity for speculation.”

Zuckerberg’s apparent generosity, it would seem, is a small contribution to a large problem that was created by the success of the industry he is involved in. In one sense, the housing grants (equivalent to the price of just one-and-a-half average Menlo Park homes) are trying to put a sticking plaster on a problem that Facebook and other Bay Area corporations aided and abetted. It would appear that Zuckerberg was redirecting a fraction of the spoils of neoliberal tech capitalism, in the name of generosity, to try to address the problems of wealth inequality created by a social and economic system that allowed those spoils to accrue in the first place.

It is easy to think of Zuckerberg as some kind of CEO hero – a once regular kid whose genius made him one of the richest men in the world, and who decided to use that wealth for the benefit of others. The image he projects is of altruism untainted by self-interest. A quick scratch of the surface reveals that the structure of Zuckerberg’s charity enterprise is informed by much more than good-hearted altruism. Even while many have applauded Zuckerberg for his generosity, the nature of this apparent charity was openly questioned from the outset.

The wording of Zuckerberg’s 2015 letter could easily have been interpreted as meaning that he was intending to donate $45bn to charity. As investigative reporter Jesse Eisinger reported at the time, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative through which this giving was to be funnelled is not a not-for-profit charitable foundation, but a limited liability company. This legal status has significant practical implications, especially when it comes to tax. As a company, the Initiative can do much more than charitable activity: its legal status gives it rights to invest in other companies, and to make political donations. Effectively the company does not restrict Zuckerberg’s decision-making as to what he wants to do with his money; he is very much the boss. Moreover, as Eisinger described it, Zuckerberg’s bold move yielded a huge return on investment in terms of public relations for Facebook, even though it appeared that he simply “moved money from one pocket to the other” while being “likely never to pay any taxes on it”.

The creation of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative – decidedly not a charity organisation – means that Zuckerberg can control the company’s investments as he sees fit, while accruing significant commercial, tax and political benefits. All of this is not to say that Zuckerberg’s motives do not include some expression of his own generosity or some genuine desire for humanity’s wellbeing and equality.

What it does suggest, however, is that when it comes to giving, the CEO approach is one in which there is no apparent incompatibility between being generous, seeking to retain control over what is given, and the expectation of reaping benefits in return. This reformulation of generosity – in which it is no longer considered incompatible with control and self-interest – is a hallmark of the “CEO society”: a society where the values associated with corporate leadership are applied to all dimensions of human endeavour.

Mark Zuckerberg was by no means the first contemporary CEO to promise and initiate large-scale donations of wealth to self-nominated good causes. In the CEO society it is positively a badge of honour for the world’s most wealthy businesspeople to create vehicles to give away their wealth. This has been institutionalised in what is known as The Giving Pledge, a philanthropy campaign initiated by Warren Buffett and Bill Gates in 2010. The campaign targets billionaires around the world, encouraging them to give away the majority of their wealth. There is nothing in the pledge that specifies what exactly the donations will be used for, or even whether they are to be made now or willed after death; it is just a general commitment to using private wealth for ostensibly public good. It is not legally binding either, but a moral commitment.

There is a long list of people and families who have made the pledge. Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan are there, and so are some 174 others, including household names such as Richard and Joan Branson, Michael Bloomberg, Barron Hilton and David Rockefeller. It would seem that many of the world’s richest people simply want to give their money away to good causes. This all amounts to what human geographers Iain Hay and Samantha Muller sceptically refer to as a “golden age of philanthropy”, in which, since the late 1990s, bequests to charity from the super-rich have escalated to the hundreds of billions of dollars. These new philanthropists bring to charity an “entrepreneurial disposition”, Hay and Muller wrote in a 2014 paper, yet one that they suggest has been “diverting attention and resources away from the failings of contemporary manifestations of capitalism”, and may also be serving as a substitute for public spending withdrawn by the state.

A protester outside the Nasdaq headquarters in New York marks Facebook’s IPO, 2012. Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

The recent development of philanthrocapitalism also marks the increasing encroachment of business into the provision of public goods and services. This encroachment is not limited to the activities of individual billionaires; it is also becoming a part of the activities of large corporations under the rubric of CSR. This is especially the case for large multinational corporations whose global reach, wealth and power give them significant political clout. This relationship has been referred to as “political CSR”. Business ethics professors Andreas Scherer and Guido Palazzo note that, for large corporations, “CSR is increasingly displayed in corporate involvement in the political process of solving societal problems, often on a global scale”. Such political CSR initiatives see organisations cooperating and collaborating with governments, civic bodies and international institutions, so that historical separations between the purposes of the state and the corporations are increasingly eroded.

Global corporations have long been involved in quasi-governmental activities such as the setting of standards and codes, and today are increasingly engaging in other activities that have traditionally been the domain of government, such as public health provision, education, the protection of human rights, addressing social problems such as Aids and malnutrition, protection of the natural environment and the promotion of peace and social stability.

Today, large organisations can amass significant economic and political power, on a global scale. This means that their actions – and the way those actions are regulated – have far-reaching social consequences. The balanced tipped in 2000, when the Institute for Policy Studies in the US reported, after comparing corporate revenues with gross domestic product (GDP), that 51 of the largest economies in the world were corporations, and 49 were national economies. The biggest corporations were General Motors, Walmart and Ford, each of which was larger economically than Poland, Norway and South Africa. As the heads of these corporations, CEOs are now quasi-politicians. One only has to think of the increasing power of the World Economic Forum, whose annual meeting in Davos in Switzerland sees corporate CEOs and senior politicians getting together with the ostensible goal of “improving the world”, a now time-honoured ritual that symbolises the global power and agency of CEOs.

The development of CSR is not the result of self-directed corporate initiatives for doing good deeds, but a response to widespread CSR activism from NGOs, pressure groups and trade unions. Often this has been in response to the failure of governments to regulate large corporations. High-profile industrial accidents and scandals have also put pressure on organisations for heightened self-regulation.

An explosion at a Union Carbide chemical plant in Bhopal, India in 1984 led to the deaths of an estimated 25,000 people. James Post, a professor of management at Boston University, explains that, after the disaster, “the global chemical industry recognised that it was nearly impossible to secure a licence to operate without public confidence in industry safety standards. The Chemical Manufacturers Association (CMA) adopted a code of conduct, including new standards of product stewardship, disclosure and community engagement.”

The impetus for this was corporate self-interest, rather than generosity, as industries and corporations globally “began to recognise the increasing importance of reputation and image”. Similar moves were enacted after other major industrial accidents, such as the Exxon Valdez oil tanker spilling hundreds of thousands of barrels of oil in Alaska in 1989, and BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploding in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010.

In the CEO society, corporate logic such as this rules supreme, and ensures that any activities thought of as generous and socially responsible ultimately have a payoff in terms of self-interest. If there was ever a debate between the ethics of genuine hospitality, reciprocity and self-interest, it is not to be found here. It is in accordance with this CEO logic that the mechanisms for redressing the inequality created through wealth generation are placed in the hands of the wealthy, and in a way that ultimately benefits them. The worst excesses of neoliberal capitalism are morally justified by the actions of the very people who benefit from those excesses. Wealth redistribution is placed in the hands of the wealthy, and social responsibility in the hands of those who have exploited society for personal gain.

Meanwhile, inequality is growing, and both corporations and the wealthy find ways to avoid the taxes that the rest of us pay. In the name of generosity, we find a new form of corporate rule, refashioning another dimension of human endeavour in its own interests. Such is a society where CEOs are no longer content to do business; they must control public goods as well. In the end, while the Giving Pledge’s website may feature more and more smiling faces of smug-looking CEOs, the real story is of a world characterised by gross inequality that is getting worse year by year.

In February 2017, Facebook’s founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg was in the headlines for his charitable activities. The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, founded by the tech billionaire and his wife, Priscilla Chan, handed out over $3m in grants to aid the housing crisis in the Silicon Valley area. David Plouffe, the Initiative’s president of policy and advocacy, stated that the grants were intended to “support those working to help families in immediate crisis while supporting research into new ideas to find a long-term solution – a two-step strategy that will guide much of our policy and advocacy work moving forward”.

This is but one small part of Zuckerberg’s charity empire. The Initiative has committed billions of dollars to philanthropic projects designed to address social problems, with a special focus on solutions driven by science, medical research and education. This all took off in December 2015, when Zuckerberg and Chan wrote and published a letter to their new baby Max. The letter made a commitment that over the course of their lives they would donate 99% of their shares in Facebook (at the time valued at $45bn) to the “mission” of “advancing human potential and promoting equality”.

The housing intervention is of course much closer to home, dealing with issues literally at the door of Facebook’s Menlo Park head office. This is an area where median house prices almost doubled to around $2m in the five years between 2012 and 2017.

More generally, San Francisco is a city with massive income inequality, and the reputation of having the most expensive housing in the US. Chan Zuckerberg’s intervention was clearly designed to offset social and economic problems caused by rents and house prices having skyrocketed to such a level that even tech workers on six-figure salaries find it hard to get by. For those on more modest incomes, supporting themselves, let alone a family, is nigh-on impossible.

Ironically, the boom in the tech industry in this region – a boom Facebook has been at the forefront of – has been a major contributor to the crisis. As Peter Cohen from the Council of Community Housing Organizations explained it: “When you’re dealing with this total concentration of wealth and this absurd slosh of real-estate money, you’re not dealing with housing that’s serving a growing population. You’re dealing with housing as a real-estate commodity for speculation.”

Zuckerberg’s apparent generosity, it would seem, is a small contribution to a large problem that was created by the success of the industry he is involved in. In one sense, the housing grants (equivalent to the price of just one-and-a-half average Menlo Park homes) are trying to put a sticking plaster on a problem that Facebook and other Bay Area corporations aided and abetted. It would appear that Zuckerberg was redirecting a fraction of the spoils of neoliberal tech capitalism, in the name of generosity, to try to address the problems of wealth inequality created by a social and economic system that allowed those spoils to accrue in the first place.

It is easy to think of Zuckerberg as some kind of CEO hero – a once regular kid whose genius made him one of the richest men in the world, and who decided to use that wealth for the benefit of others. The image he projects is of altruism untainted by self-interest. A quick scratch of the surface reveals that the structure of Zuckerberg’s charity enterprise is informed by much more than good-hearted altruism. Even while many have applauded Zuckerberg for his generosity, the nature of this apparent charity was openly questioned from the outset.

The wording of Zuckerberg’s 2015 letter could easily have been interpreted as meaning that he was intending to donate $45bn to charity. As investigative reporter Jesse Eisinger reported at the time, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative through which this giving was to be funnelled is not a not-for-profit charitable foundation, but a limited liability company. This legal status has significant practical implications, especially when it comes to tax. As a company, the Initiative can do much more than charitable activity: its legal status gives it rights to invest in other companies, and to make political donations. Effectively the company does not restrict Zuckerberg’s decision-making as to what he wants to do with his money; he is very much the boss. Moreover, as Eisinger described it, Zuckerberg’s bold move yielded a huge return on investment in terms of public relations for Facebook, even though it appeared that he simply “moved money from one pocket to the other” while being “likely never to pay any taxes on it”.

The creation of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative – decidedly not a charity organisation – means that Zuckerberg can control the company’s investments as he sees fit, while accruing significant commercial, tax and political benefits. All of this is not to say that Zuckerberg’s motives do not include some expression of his own generosity or some genuine desire for humanity’s wellbeing and equality.

What it does suggest, however, is that when it comes to giving, the CEO approach is one in which there is no apparent incompatibility between being generous, seeking to retain control over what is given, and the expectation of reaping benefits in return. This reformulation of generosity – in which it is no longer considered incompatible with control and self-interest – is a hallmark of the “CEO society”: a society where the values associated with corporate leadership are applied to all dimensions of human endeavour.

Mark Zuckerberg was by no means the first contemporary CEO to promise and initiate large-scale donations of wealth to self-nominated good causes. In the CEO society it is positively a badge of honour for the world’s most wealthy businesspeople to create vehicles to give away their wealth. This has been institutionalised in what is known as The Giving Pledge, a philanthropy campaign initiated by Warren Buffett and Bill Gates in 2010. The campaign targets billionaires around the world, encouraging them to give away the majority of their wealth. There is nothing in the pledge that specifies what exactly the donations will be used for, or even whether they are to be made now or willed after death; it is just a general commitment to using private wealth for ostensibly public good. It is not legally binding either, but a moral commitment.

There is a long list of people and families who have made the pledge. Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan are there, and so are some 174 others, including household names such as Richard and Joan Branson, Michael Bloomberg, Barron Hilton and David Rockefeller. It would seem that many of the world’s richest people simply want to give their money away to good causes. This all amounts to what human geographers Iain Hay and Samantha Muller sceptically refer to as a “golden age of philanthropy”, in which, since the late 1990s, bequests to charity from the super-rich have escalated to the hundreds of billions of dollars. These new philanthropists bring to charity an “entrepreneurial disposition”, Hay and Muller wrote in a 2014 paper, yet one that they suggest has been “diverting attention and resources away from the failings of contemporary manifestations of capitalism”, and may also be serving as a substitute for public spending withdrawn by the state.

Warren Buffett announces a $30bn donation to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, 2006. Photograph: Justin Lane/EPA

Essentially, what we are witnessing is the transfer of responsibility for public goods and services from democratic institutions to the wealthy, to be administered by an executive class. In the CEO society, the exercise of social responsibilities is no longer debated in terms of whether corporations should or shouldn’t be responsible for more than their own business interests. Instead, it is about how philanthropy can be used to reinforce a politico-economic system that enables such a small number of people to accumulate obscene amounts of wealth. Zuckerberg’s investment in solutions to the Bay Area housing crisis is an example of this broader trend.

The reliance on billionaire businesspeople’s charity to support public projects is a part of what has been called “philanthrocapitalism”. This resolves the apparent antinomy between charity (traditionally focused on giving) and capitalism (based on the pursuit of economic self-interest). As historian Mikkel Thorup explains, philanthrocapitalism rests on the claim that “capitalist mechanisms are superior to all others (especially the state) when it comes to not only creating economic but also human progress, and that the market and market actors are or should be made the prime creators of the good society”.

The golden age of philanthropy is not just about benefits that accrue to individual givers. More broadly, philanthropy serves to legitimise capitalism, as well as to extend it further and further into all domains of social, cultural and political activity.

Philanthrocapitalism is about much more than the simple act of generosity it pretends to be, instead involving the inculcation of neoliberal values personified by the billionaire CEOs who have led its charge. Philanthropy is recast in the same terms in which a CEO would consider a business venture. Charitable giving is translated into a business model that employs market-based solutions characterised by efficiency and quantified costs and benefits.

Philanthrocapitalism takes the application of management discourses and practices from business corporations and adapts them to charitable work. The focus is on entrepreneurship, market-based approaches and performance metrics. The process is funded by super-rich businesspeople and managed by those experienced in business. The result, at a practical level, is that philanthropy is undertaken by CEOs in a manner similar to how they would run businesses.

As part of this, charitable foundations have changed in recent years. As explained in a paper by Garry Jenkins, a professor of law at the University of Minnesota, this involves becoming “increasingly directive, controlling, metric-focused and business-oriented with respect to their interactions with grantee public charities, in an attempt to demonstrate that the work of the foundation is ‘strategic’ and ‘accountable’”.

This is far from the benign shift to a different and better way of doing things that it claims to be – a CEO style to “save the world through business thinking and market methods”, as Jenkins puts it. Instead, the risk of philanthrocapitalism is a takeover of charity by business interests, such that generosity to others is appropriated into the overarching dominance of the CEO model of society and its corporate institutions.

The modern CEO is very much at the forefront of the political and media stage. While this often leads to CEOs becoming vaunted celebrities, it also leaves them open to being identified as scapegoats for economic injustice. The increasingly public role taken by CEOs is related to a renewed corporate focus on their wider social responsibility. Firms must now balance, at least rhetorically, a dual commitment to profit and social outcomes. This has been reflected in the promotion of the “triple bottom line”, which combines social, financial and environmental priorities in corporate reporting.

This turn toward social responsibility represents a distinct problem for CEOs. While firms may be willing to sacrifice some short-term profit for the sake of preserving their public reputation, this same bargain is rarely on offer to CEOs themselves, who are judged on their quarterly reports and how well they are serving the fiscal interests of their shareholders. Thus, whereas social responsibility strategies may win public kudos, in the confines of the boardroom it is often a different story, especially when the budget is being scrutinised.

There is a further economic incentive for CEOs to avoid making fundamental changes to their operations in the name of social justice, in that a large portion of CEO remuneration often consists of company stock and options. Accepting fair trade policies and closing sweatshops may be good for the world, but is potentially disastrous for a firm’s immediate financial success. What is ethically valuable to the voting and buying public is not necessarily of concrete value to corporations, nor personally beneficial to their top executives.

Many firms have sought to resolve this contradiction through high-profile philanthropy. Exploitative labour practices or corporate malpractice are swept under the carpet as companies publicise tax-efficient contributions to good causes. Such contributions may be a relatively small price to pay compared with changing fundamental operational practices. Likewise, giving to charity is a prime opportunity for CEOs to be seen to be doing good without having to sacrifice their commitment to making profit at any social cost. Charitable activity permits CEOs to be philanthropic rather than economically progressive or politically democratic.

There is an even more straightforward financial consideration at play in some cases. Charity can be an absolute boon to capital accumulation: corporate philanthropy has been shown to have a positive effect on perceptions by stock market analysts. At the personal level, CEOs can take advantage of promoting their individual charity to distract from other, less savoury activities; as an executive, they can cash in on the capital gains that can be made from introducing high-profile charity strategies.

The very notion of corporate social responsibility, or CSR, has been criticised for providing companies with a moral cover to act in quite exploitative and socially damaging ways. But in the current era, social responsibility, when portrayed as an individual character trait of chief executives, has allowed corporations to be run as irresponsibly as ever. CEOs’ very public engagement in philanthrocapitalism can be understood as a key component of this reputation management. It is part of the marketing of the firm itself, as the good deeds of its leaders come to signify the overall goodness of the corporation.

Ironically, philanthrocapitalism also grants corporations the moral right, at least within the public consciousness, to be socially irresponsible. The trumpeting of the CEOs’ personal generosity can grant an implicit right for their corporations to act ruthlessly and with little consideration for the broader social effects of their activities. This reflects a productive tension at the heart of modern CSR: the more moral a CEO, the more immoral their company can in theory seek to be.

The hypocrisy revealed by CEOs claiming to be dedicated to social responsibility and charity also exposes a deeper authoritarian morality that prevails in the CEO society. Philanthrocapitalism is commonly presented as the social justice component of an otherwise amoral global free market. At best, corporate charity is a type of voluntary tax paid by the 1% for their role in creating such an economically deprived and unequal world. Yet this “giving” culture also helps support and spread a distinctly authoritarian form of economic development that mirrors the autocratic leadership style of the executives who predominantly fund it.

The marketisation of global charity and empowerment has dangerous implications that transcend economics. It also has a troubling emerging political legacy, one in which democracy is sacrificed on that altar of executive-style empowerment. Politically, the free market is posited as a fundamental requirement for liberal democracy. However, recent analysis reveals the deeper connection between processes of marketisation and authoritarianism. In particular, a strong government is required to implement these often unpopular market changes. The image of the powerful autocrat is, to this effect, transformed into a potentially positive figure, a forward-thinking political leader who can guide their country on the correct market path in the face of “irrational” opposition. Charity becomes a conduit for CEOs to fund these “good” authoritarians.

Essentially, what we are witnessing is the transfer of responsibility for public goods and services from democratic institutions to the wealthy, to be administered by an executive class. In the CEO society, the exercise of social responsibilities is no longer debated in terms of whether corporations should or shouldn’t be responsible for more than their own business interests. Instead, it is about how philanthropy can be used to reinforce a politico-economic system that enables such a small number of people to accumulate obscene amounts of wealth. Zuckerberg’s investment in solutions to the Bay Area housing crisis is an example of this broader trend.

The reliance on billionaire businesspeople’s charity to support public projects is a part of what has been called “philanthrocapitalism”. This resolves the apparent antinomy between charity (traditionally focused on giving) and capitalism (based on the pursuit of economic self-interest). As historian Mikkel Thorup explains, philanthrocapitalism rests on the claim that “capitalist mechanisms are superior to all others (especially the state) when it comes to not only creating economic but also human progress, and that the market and market actors are or should be made the prime creators of the good society”.

The golden age of philanthropy is not just about benefits that accrue to individual givers. More broadly, philanthropy serves to legitimise capitalism, as well as to extend it further and further into all domains of social, cultural and political activity.

Philanthrocapitalism is about much more than the simple act of generosity it pretends to be, instead involving the inculcation of neoliberal values personified by the billionaire CEOs who have led its charge. Philanthropy is recast in the same terms in which a CEO would consider a business venture. Charitable giving is translated into a business model that employs market-based solutions characterised by efficiency and quantified costs and benefits.

Philanthrocapitalism takes the application of management discourses and practices from business corporations and adapts them to charitable work. The focus is on entrepreneurship, market-based approaches and performance metrics. The process is funded by super-rich businesspeople and managed by those experienced in business. The result, at a practical level, is that philanthropy is undertaken by CEOs in a manner similar to how they would run businesses.

As part of this, charitable foundations have changed in recent years. As explained in a paper by Garry Jenkins, a professor of law at the University of Minnesota, this involves becoming “increasingly directive, controlling, metric-focused and business-oriented with respect to their interactions with grantee public charities, in an attempt to demonstrate that the work of the foundation is ‘strategic’ and ‘accountable’”.

This is far from the benign shift to a different and better way of doing things that it claims to be – a CEO style to “save the world through business thinking and market methods”, as Jenkins puts it. Instead, the risk of philanthrocapitalism is a takeover of charity by business interests, such that generosity to others is appropriated into the overarching dominance of the CEO model of society and its corporate institutions.

The modern CEO is very much at the forefront of the political and media stage. While this often leads to CEOs becoming vaunted celebrities, it also leaves them open to being identified as scapegoats for economic injustice. The increasingly public role taken by CEOs is related to a renewed corporate focus on their wider social responsibility. Firms must now balance, at least rhetorically, a dual commitment to profit and social outcomes. This has been reflected in the promotion of the “triple bottom line”, which combines social, financial and environmental priorities in corporate reporting.

This turn toward social responsibility represents a distinct problem for CEOs. While firms may be willing to sacrifice some short-term profit for the sake of preserving their public reputation, this same bargain is rarely on offer to CEOs themselves, who are judged on their quarterly reports and how well they are serving the fiscal interests of their shareholders. Thus, whereas social responsibility strategies may win public kudos, in the confines of the boardroom it is often a different story, especially when the budget is being scrutinised.

There is a further economic incentive for CEOs to avoid making fundamental changes to their operations in the name of social justice, in that a large portion of CEO remuneration often consists of company stock and options. Accepting fair trade policies and closing sweatshops may be good for the world, but is potentially disastrous for a firm’s immediate financial success. What is ethically valuable to the voting and buying public is not necessarily of concrete value to corporations, nor personally beneficial to their top executives.

Many firms have sought to resolve this contradiction through high-profile philanthropy. Exploitative labour practices or corporate malpractice are swept under the carpet as companies publicise tax-efficient contributions to good causes. Such contributions may be a relatively small price to pay compared with changing fundamental operational practices. Likewise, giving to charity is a prime opportunity for CEOs to be seen to be doing good without having to sacrifice their commitment to making profit at any social cost. Charitable activity permits CEOs to be philanthropic rather than economically progressive or politically democratic.

There is an even more straightforward financial consideration at play in some cases. Charity can be an absolute boon to capital accumulation: corporate philanthropy has been shown to have a positive effect on perceptions by stock market analysts. At the personal level, CEOs can take advantage of promoting their individual charity to distract from other, less savoury activities; as an executive, they can cash in on the capital gains that can be made from introducing high-profile charity strategies.

The very notion of corporate social responsibility, or CSR, has been criticised for providing companies with a moral cover to act in quite exploitative and socially damaging ways. But in the current era, social responsibility, when portrayed as an individual character trait of chief executives, has allowed corporations to be run as irresponsibly as ever. CEOs’ very public engagement in philanthrocapitalism can be understood as a key component of this reputation management. It is part of the marketing of the firm itself, as the good deeds of its leaders come to signify the overall goodness of the corporation.