Frederik Obermaier and Bastian Obermayer in The Guardian

According to Navi Pillay, the former UN high commissioner for human rights, ‘The money stolen through corruption every year is enough to feed the world’s hungry 80 times over.’ Photograph: Arnulfo Franco/AP

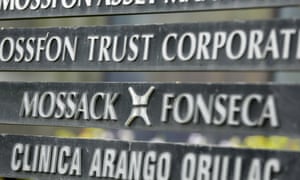

Two years ago we published the Panama Papers after an anonymous source provided 2.6 terabytes of internal data from the dubious Panamanian law firm of Mossack Fonseca. We shared the data with 400 journalists worldwide and together revealed how the wealthy and powerful use shell companies to hide their assets. Such companies are exploited by dictators, drug cartels, mafia clans, fraudsters, weapons dealers and regimes like North Korea and Iran to hide their shady business transactions.

As a consequence, Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, the prime minister of Iceland, resigned. Pakistani prime minister Nawaz Sharif did the same, and in the United Kingdom even David Cameron’s father was implicated. So far, the Panama Papers have helped tax authorities around the world to recover more than $500m in unpaid taxes and penalties. It could be far more if lawmakers finally take action.

After publishing the Panama Papers, we have heard a lot of promises from politicians around the world. They have talked about the need for transparency, and while the discussion is warm, the details are complicated: a multilateral exchange of information and stronger anti-money laundering regulations are as difficult to implement and control as they sound.

But why bother? There is a far less bureaucratic and more powerful measure: public beneficial ownership registries. Databases in which citizens can easily access and explore the owners of companies. Not the nominee director, not the fake shareholder – the real owner. The person at the center of the matryoshka-like corporate structures, or, as experts refer to them: the ultimate beneficial owner of a company.

A database of actual owners would enable companies to check with whom they are actually doing business with. It would enable activists, journalists and skeptical citizens to investigate the individuals running dubious companies which earn millions in alleged “consulting contracts”, which are in many cases nothing more than concealed payments of corruption money. It would also give prosecutors the opportunity to follow dark money without having to rely on nerve-racking, time-consuming legal maneuvers with foreign governments.

Searchable by company and by individual names, it would enable investigators to see if Dictator X or Autocrat Y owns companies in Country Z. Combined with a public property register, it would narrow, if not close, loopholes which allow oligarchs and their relatives to betray their own citizens and stash plundered money across the globe.

Creating beneficial ownership registries will not be easy. Recently, the UK House of Lords rejected an attempt to force overseas territories under British control to create said registries. And in the United States, where some states make it more difficult to vote than to start a company, there has yet to be any reasonable public discussion about creating these transparent registries, making America a willing accomplice in global corruption. The treasury department in 2015 estimated that approximately $300bn in illicit proceeds are generated in the US per year!

Critics of public beneficial ownership registries often say that exposing company owners could put them in danger of blackmail or even kidnapping. However, no data supports such claims and there will likely never be any. As it is, the financial elite often surround themselves with the symbols and spoils of wealth, such as big cars, yachts and villas. There is no desire to hide their treasure; in fact, they often flaunt it.

Corruption is a scourge. It hits the poor first and hits them hard. Whole continents are plundered, the proceeds of human trafficking are laundered, wars are financed and violent religious extremism is supported.

The word “corruption” comes from the Latin “corrumpere”, which can mean “to destroy”. Corruption destroys democracy. Corruption costs citizens extraordinary amounts of money. According to estimates, corruption consumes more than 5% of the global gross domestic product.

Developing regions lose more than 10 times the money they receive in foreign aid to illicit financial schemes. Without corruption and the shell companies that make it possible, there might be no need for aid to Africa or Asia. Most importantly, corruption kills. According to Navi Pillay, the former United Nations high commissioner for human rights, “The money stolen through corruption every year is enough to feed the world’s hungry 80 times over”.

As Louis Brandeis, the late associate justice of the supreme court of the United States, once pointed out sunlight is the best disinfectant. Hence let the sunshine in! Lawmakers must make public beneficial ownership registries a priority to ensure that institutions remain transparent and democratic.

There is no legitimate reason to allow individuals to own anonymous companies or to help new “entrepreneurs” to create them. Lava Jato in Brazil, the Fifa scandal and nearly every other major corruption case have involved opaque company structures created to bribe, receive bribes or to hide dirty money.

Financial crimes rely on exploiting anonymous companies and trusts, and secrecy jurisdictions like the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands and the states of Delaware and Nevada are partners in those crimes. They must be held accountable.

Waiting for a global solution means waiting a long time, if not forever. The only way to draw the corporate curtain back and expose corruption is for lawmakers to work in the public interest and create public beneficial ownership registries and public property registries now. The more countries that adopt these measures, the less places dictators, human traffickers, weapons dealers and oligarchs can hide.

Lawmakers that claim to stand against corruption should do so by fighting for these kinds of registries now, or forever hold their peace.

Two years ago we published the Panama Papers after an anonymous source provided 2.6 terabytes of internal data from the dubious Panamanian law firm of Mossack Fonseca. We shared the data with 400 journalists worldwide and together revealed how the wealthy and powerful use shell companies to hide their assets. Such companies are exploited by dictators, drug cartels, mafia clans, fraudsters, weapons dealers and regimes like North Korea and Iran to hide their shady business transactions.

As a consequence, Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, the prime minister of Iceland, resigned. Pakistani prime minister Nawaz Sharif did the same, and in the United Kingdom even David Cameron’s father was implicated. So far, the Panama Papers have helped tax authorities around the world to recover more than $500m in unpaid taxes and penalties. It could be far more if lawmakers finally take action.

After publishing the Panama Papers, we have heard a lot of promises from politicians around the world. They have talked about the need for transparency, and while the discussion is warm, the details are complicated: a multilateral exchange of information and stronger anti-money laundering regulations are as difficult to implement and control as they sound.

But why bother? There is a far less bureaucratic and more powerful measure: public beneficial ownership registries. Databases in which citizens can easily access and explore the owners of companies. Not the nominee director, not the fake shareholder – the real owner. The person at the center of the matryoshka-like corporate structures, or, as experts refer to them: the ultimate beneficial owner of a company.

A database of actual owners would enable companies to check with whom they are actually doing business with. It would enable activists, journalists and skeptical citizens to investigate the individuals running dubious companies which earn millions in alleged “consulting contracts”, which are in many cases nothing more than concealed payments of corruption money. It would also give prosecutors the opportunity to follow dark money without having to rely on nerve-racking, time-consuming legal maneuvers with foreign governments.

Searchable by company and by individual names, it would enable investigators to see if Dictator X or Autocrat Y owns companies in Country Z. Combined with a public property register, it would narrow, if not close, loopholes which allow oligarchs and their relatives to betray their own citizens and stash plundered money across the globe.

Creating beneficial ownership registries will not be easy. Recently, the UK House of Lords rejected an attempt to force overseas territories under British control to create said registries. And in the United States, where some states make it more difficult to vote than to start a company, there has yet to be any reasonable public discussion about creating these transparent registries, making America a willing accomplice in global corruption. The treasury department in 2015 estimated that approximately $300bn in illicit proceeds are generated in the US per year!

Critics of public beneficial ownership registries often say that exposing company owners could put them in danger of blackmail or even kidnapping. However, no data supports such claims and there will likely never be any. As it is, the financial elite often surround themselves with the symbols and spoils of wealth, such as big cars, yachts and villas. There is no desire to hide their treasure; in fact, they often flaunt it.

Corruption is a scourge. It hits the poor first and hits them hard. Whole continents are plundered, the proceeds of human trafficking are laundered, wars are financed and violent religious extremism is supported.

The word “corruption” comes from the Latin “corrumpere”, which can mean “to destroy”. Corruption destroys democracy. Corruption costs citizens extraordinary amounts of money. According to estimates, corruption consumes more than 5% of the global gross domestic product.

Developing regions lose more than 10 times the money they receive in foreign aid to illicit financial schemes. Without corruption and the shell companies that make it possible, there might be no need for aid to Africa or Asia. Most importantly, corruption kills. According to Navi Pillay, the former United Nations high commissioner for human rights, “The money stolen through corruption every year is enough to feed the world’s hungry 80 times over”.

As Louis Brandeis, the late associate justice of the supreme court of the United States, once pointed out sunlight is the best disinfectant. Hence let the sunshine in! Lawmakers must make public beneficial ownership registries a priority to ensure that institutions remain transparent and democratic.

There is no legitimate reason to allow individuals to own anonymous companies or to help new “entrepreneurs” to create them. Lava Jato in Brazil, the Fifa scandal and nearly every other major corruption case have involved opaque company structures created to bribe, receive bribes or to hide dirty money.

Financial crimes rely on exploiting anonymous companies and trusts, and secrecy jurisdictions like the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands and the states of Delaware and Nevada are partners in those crimes. They must be held accountable.

Waiting for a global solution means waiting a long time, if not forever. The only way to draw the corporate curtain back and expose corruption is for lawmakers to work in the public interest and create public beneficial ownership registries and public property registries now. The more countries that adopt these measures, the less places dictators, human traffickers, weapons dealers and oligarchs can hide.

Lawmakers that claim to stand against corruption should do so by fighting for these kinds of registries now, or forever hold their peace.

Image copyrightREUTERSImage captionThe Bank of England did not get its way against the Treasury

Image copyrightREUTERSImage captionThe Bank of England did not get its way against the Treasury

Jeremy Corbyn filed his tax return late AFP

Jeremy Corbyn filed his tax return late AFP