Brinda Karat in The Hindu

The Supreme Court did not allow itself to be converted into a khap panchayat, although it came close to it on Tuesday as it heard the Hadiya case. The counsel for the National Investigation Agency (NIA) supported by the legal counsel of the Central government made out a case of indoctrination and brainwashing in a conspiracy of ‘love jehad’ which they claimed rendered Hadiya incapacitated and invalidated her consent. The NIA wanted the court to study the documents it claimed it had as evidence before they heard Hadiya. For one and a half hours, this young woman stood in open court hearing arguments about herself, against herself and her chosen partner. It was shameful, humiliating and set an unfortunate precedent. If the court was not clear that it wanted to hear her, why did they call her at all? She should never have been subjected to that kind of indignity. She is not a criminal but she was treated like one for that period of time.

The right to speak

The court remained undecided even in the face of the compelling argument by lawyers Kapil Sibal and Indira Jaising representing Hadiya’s husband Shafin Jahan that the most critical issue was that of the right of an adult woman to make her own choice. The court almost adjourned for the day when the Kerala State Women’s Commission lawyer, P. V. Dinesh, raised a voice of outrage that after all the accusations against Hadiya in the open court if the court did not hear her, it would be a grave miscarriage of justice. In khap panchayats, the woman accused of breaking the so-called honour code is never allowed to speak. Her sentence begins with her enforced silence and ends with whatever dreadful punishment is meted out to her by the khap. Fortunately the Supreme Court pulled itself back from the brink and agreed to give Hadiya an opportunity to speak.

There was no ambiguity about what she said. It was the courage of her conviction that stood out. She wanted to be treated as a human being. She wanted her faith to be respected. She wanted to study. She wanted to be with her husband. And most importantly, she wanted her freedom.

The court listened, but did it hear?

Both sides claim they are happy with the order. Hadiya and her husband feel vindicated because the court has ended her enforced custody by her father. She has got an opportunity to resume her studies. Lawyers representing the couple’s interests have explained that the first and main legal strategy was to ensure her liberty from custody which has been achieved. They say that the order places no restrictions on Hadiya meeting anyone she chooses to, including her husband. It is a state of interim relief.

Her father claims victory because the court did not accept Hadiya’s request to leave the court with her husband. Instead the court directed that she go straight to a hostel in Salem to continue her studies. He asserted this will ensure that she is not with her husband who he has termed a terrorist.

The next court hearing is in January and the way the court order is implemented will be clear by then.

The case reveals how deeply the current climate created by sectarian ideologies based on a narrow reading of religious identity has pushed back women’s rights to autonomy as equal citizens. From the government to the courts, to the strengthening of conservative and regressive thinking and practice, it’s all out there in Hadiya’s case.

One of the most disturbing fallouts is that the term ‘love jehad’ used by Hindutva zealots to target inter-faith marriages has been given legal recognition and respectability by the highest courts. An agency whose proclaimed mandate is to investigate offences related to terrorism has now expanded its mandate by order of the Supreme Court to unearth so-called conspiracies of Muslim men luring Hindu women into marriage and forcibly converting them with the aim of joining the Islamic State. The underlying assumption is that Hindu women who marry Muslims have no minds of their own. If they convert to Islam, that itself is proof enough of a conspiracy.

This was clearly reflected in the regressive order of the Kerala High Court in May this year which annulled Hadiya’s marriage. Among other most objectionable comments it held that a woman of 24 is “weak and vulnerable”, that as per Indian tradition, the custody of an unmarried daughter is with the parents, until she is properly married.” Equally shocking, it ordered that nobody could meet her except her parents in whose custody she was placed.

Not a good precedent

Courts in this country are expected to uphold the right of an adult woman to her choice of a partner. Women’s autonomy and equal citizenship rights flow from the constitutional framework, not from religious authority or tradition. The Kerala High Court judgement should be struck down by the apex court. We cannot afford to have such a judgment as legal precedent.

The case also bring into focus the right to practice and propagate the religion of one’s choice under the Constitution. In Hadiya’s case she has made it clear time and again that she converted because of her belief in Islam. It is not a forcible conversion. Moreover she converted at least a year before her marriage. So the issue of ‘love jehad’ in any case is irrelevant and the court cannot interfere with her right to convert.

As far as the NIA investigation is concerned, the Supreme Court has ordered that it should continue. The Kerala government gave an additional affidavit in October stating that “the investigation conducted so far by the Kerala police has not revealed any incident relating to commission of any scheduled offences to make a report to the Central government under Section 6 of the National Investigation Agency Act of 2008.” The State government said the police investigation was on when the Supreme Court directed the NIA to conduct an investigation into the case. It thus opposed the handing over of the case to the NIA. In the light of this clear stand of the Kerala government, it is inexplicable why its counsel in the Supreme Court should take a contrary stand in the hearing — this should be rectified at the earliest.

Vigilantism by another name

The NIA is on a fishing expedition having already interrogated 89 such couples in Kerala. Instead of inter-caste and inter-community marriages being celebrated as symbols of India’s open and liberal approach, they are being treated as suspect.

Now, every inter-faith couple will be vulnerable to attacks by gangs equivalent to the notorious gau rakshaks. This is not just applicable to cases where a Hindu woman marries a Muslim. There are bigots and fanatics in all communities. When a Muslim woman marries a Hindu, Muslim fundamentalist organisations like the Popular Front of India use violent means to prevent such marriages. Sworn enemies, such as those who belong to fundamentalist organisations in the name of this or that religion, have more in common with each other than they would care to admit.

Hopefully the Supreme Court will act in a way which strengthens women’s rights unencumbered by subjective interpretations of tradition and communal readings of what constitutes national interest.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Thursday, 30 November 2017

Wednesday, 29 November 2017

Beware the Tory cult that’s steering Brexit

Simon Kuper in The FT

In South Africa in 1856, the spirits of three ancestors visited a 15-year-old Xhosa girl called Nongqawuse. According to her uncle, who spoke for her, the spirits wanted the Xhosa to destroy their crops and cattle. The tribe’s ancestors would then return and drive the white settlers into the ocean. New, beautiful cattle would appear. The sun would turn red. The Xhosa duly began killing cattle and burning crops. This type of self-destructive quest for riches and freedom is now known as a “cargo cult”. (The word “cargo” denotes the western goods the tribe hopes to obtain.)

In South Africa in 1856, the spirits of three ancestors visited a 15-year-old Xhosa girl called Nongqawuse. According to her uncle, who spoke for her, the spirits wanted the Xhosa to destroy their crops and cattle. The tribe’s ancestors would then return and drive the white settlers into the ocean. New, beautiful cattle would appear. The sun would turn red. The Xhosa duly began killing cattle and burning crops. This type of self-destructive quest for riches and freedom is now known as a “cargo cult”. (The word “cargo” denotes the western goods the tribe hopes to obtain.)

Brexit voters come in endless varieties. However, the particular sect now steering Brexit — the Europhobe wing of the Conservative party — is turning into a cargo cult.

At the heart of it is ancestor worship. There’s a widespread belief in Britain that “the past is the real us”, says Catherine Fieschi, head of the Counterpoint think-tank. Perhaps no other country has as happy a relationship with its chequered history. And the self-appointed guardian of this relationship is the Conservative party.

Hardly any of today’s Tories actually remember Britain’s golden age of ruling India and winning the second world war. Even the party’s ageing members are merely the children of the Dunkirk generation. Economically, they have been the luckiest cohort in British history. But they and many other Tory MPs feel the shame of late birth. They disdain the UK’s tame, vegetarian, low-stakes, Brussels-based, post-imperial incarnation, which in 70 years offered nothing more glorious than the Falklands war. Now they have their own heroic project: Brexit.

Cargo cults typically start when the tribe feels it is in decline, surpassed by foreigners. In Melanesia, the Pacific region with a tradition of cargo cults, locals came to feel like “rubbish men” (the phrase is pidgin English) in comparison with rich Europeans. “A recurring feature of these cults is a belief that Europeans in some past age tricked Melanesians and are withholding from them their rightful share of material goods,” writes Paul Sillitoe, an anthropologist at Durham University.

To get these goods, the tribe has to mimic modern rituals that seem to have made advanced societies rich. Melanesians built airfields to receive the ancestors’ cargo. The Brexiter flies around signing trade deals. Meanwhile, the inferior goods of today’s “rubbish men” must be destroyed. Hence the eagerness in this Tory sect (but not among the British population at large) to shut off trade with Europe. If the correct rituals are followed, the ancestors will return. The sect leader, Boris Johnson, in his biography of Winston Churchill, sometimes seems to cast himself as the reincarnation of the great “glory-chasing, goalmouth-hanging opportunist”.

But the cargo cult is threatened by non-believers. They can ruin things by angering the ancestors. For 15 months, Nongqawuse blamed the failure of her prophecy on the few Xhosa — amagogotya, or “stingy ones” — who refused to kill their cattle.

Now, leading Conservatives are hunting British amagogotya. Chris Heaton-Harris seeks to out Remainer university teachers, Jacob Rees-Mogg castigates the BBC and the Bank of England’s governor Mark Carney as “enemies of Brexit”, while John Redwood urges the Treasury “to have more realistic, optimistic forecasts”. The sect also suspects Theresa May and Brexit secretary David Davis of being closet amagogotya. That is probably accurate: as Britain’s point-people in the negotiations, these two sense that cattle-killing might not be a winning strategy.

Sillitoe says it’s wrong to dismiss cargo cultists as “irrational and deluded people”. In fact, he writes, “Cargo cults are a rational indigenous response to traumatic culture contact with western society.” Comical as the participants might seem, “they are neither illogical nor stupid”.

Certainly the Conservative cult follows its own logic. The aim isn’t simply to reduce immigration or boost the economy. Rather, Brexit reaffirms the tribe’s ancestral values against a disappointing modernity. The difficulty of Brexiting is part of the appeal: only a great tribe can renew itself through sacrifice. The stalling of talks with the EU is welcomed as a ritual re-enactment of Britain’s past glorious conflicts. Hence the ovations for any speaker at last month’s Conservative conference who urged walking out with no deal.

A recent blog by Pete North, a founder of the Leave Alliance, beautifully sums up many of these attitudes. North, who favoured staying in the European single market, predicts Brexit will send Britain into “a 10-year recession”. He writes: “After years of the left bleating about austerity, they are about to find out what it actually means.” And yet, he continues, “My gut instinct tells me that culturally it will be a vast improvement on the status quo.” He says modern Britons have become “spoiled and self-indulgent . . . in the absence of any real challenges or imperatives to grow as a people”. As the psychiatrist says of the TV character Basil Fawlty, there’s enough material here for an entire conference.

After the cattle-killing, many Xhosa starved to death, while flocks of vultures reportedly watched from above. Refugees who fled to the British Cape Colony were forced into serf-like labour contracts. But Nongqawuse lived on for another 40 years, albeit in exile, under a changed name.

How ‘journeys’ are the first defence for sex pests and sinners

Robert Shrimsley in The FT

I want to tell you that I’ve been on a journey — a journey away from personal responsibility. I cannot as yet tell you very much about my journey because I’m not yet clear what it is that I need to have been journeying away from. But I wanted to put it out there, just in case anyone discovers anything bad about me. Because if they do, it is important that you know that was me then, not me now, because I have been on a journey.

I want to tell you that I’ve been on a journey — a journey away from personal responsibility. I cannot as yet tell you very much about my journey because I’m not yet clear what it is that I need to have been journeying away from. But I wanted to put it out there, just in case anyone discovers anything bad about me. Because if they do, it is important that you know that was me then, not me now, because I have been on a journey.

Being on a journey is quite the thing these days. In recent weeks, a fair few people have discovered that they too have been on one. It has become the go-to excuse for anyone caught in bad behaviour that happened some time in the past. If you don’t know the way, you head straight for the door marked contrition, turn left at redemption and keep going till you reach self-righteousness.

High-profile journeymen and women include people who have posted really unpleasant comments online. Among those on a journey was a would-be Labour councillor who was on a trek away from wondering why people kept thinking that Hitler was the bad guy. And let’s be fair — who among us hasn’t been on a journey from wondering why Hitler is portrayed as the bad guy? Another journey was embarked on by a Labour MP who had been caught engaging in horrible homophobic remarks, as well as referring to women as bitches and slags. But don’t worry; he’s been on a journey and we can rest assured that he’ll never do it again.

The important thing about being on a journey is that it allows us to separate the hideous git who once made those mistakes from the really rather super human being we see today. For this, fundamentally, is a journey away from culpability, because all that bad stuff — that was old you; the you before you embarked on the journey; the you before you were caught.

But listen, you don’t need to be in the Labour party to go on a journey. Anyone with a suddenly revealed embarrassing past can join in. This is especially important for those unwise enough to have made their mistakes in the era of social media. The beauty of the journey defence is that it plays to our inner sense of fairness. Everyone makes mistakes, so we warm to those who admit to them and seem sincere in their contrition. Sadly, the successful rehabilitation of early voyagers has encouraged any miscreant to view it as the fallback du jour.

But the journey defence will get you only so far. For a start, it requires a reasonable time to have elapsed since the last offence. It is also of limited use in more serious misdemeanours. The journey defence is very good for racist comments, casual homophobia or digital misogyny. It is of little use with serious sexual harassment. For that, you are going to want to have an illness.

You may, for example, need to discover that you are a sex addict. Addiction obviously means that you bear no responsibility for your actions, which, however repellent, are entirely beyond your control. Sex addict also sounds kind of cool, certainly much better than, say, hideous predatory creep. Harvey Weinstein and Kevin Spacey have both — rather recently — discovered they suffer from this terrible affliction. I realise that forcing yourself on young women (or men) might technically be different from sex, but “groping addict” doesn’t sound quite as stylish.

After consultation with your doctors (spin-doctors, that is), you realise that you require extensive treatment at, say, the Carmel Valley Ranch golf course and spa, where you are currently undergoing an intensive course of therapy, massage and gourmet cuisine as you battle your inner demons. If you are American, you might, at this point, ask people to pray for you.

In a way, I suppose, this is also a journey but one that comes with back rubs and fine wine. Alas, the excuses and faux admissions are looking a bit too easy. The sex addicts are somewhat devalued; the journeys are too well trodden. Those seeking to evade personal responsibility are going to need to find a new path to redemption.

What military incompetence can teach us about Brexit

David Boyle in The Guardian

A fascinating article by Simon Kuper has proposed a parallel between Brexit and the strange cargo cults of Melanesia, when societies suddenly destroy their economic underpinnings in search of a golden age, because they perceive the tribe is in some kind of decline.

It is particularly relevant now that corners of the Conservative party appear to be baying for a non-negotiated Brexit. And unfortunately, as the countdown ticks by, that may well be what they get.

There is another parallel, but it comes from psychology not anthropology. It derives from an influential theory by a former military engineer-turned-psychologist, Norman Dixon. His book, On the Psychology of Military Incompetence, was published in 1976, and has been in print ever since. His ideas may draw too much on Freudian concepts for current tastes, but there are worrying parallels to the phenomenon that he identified: the syndrome that seemed to lie behind so many British military disasters.

His thesis was that the old idea that military incompetence was something to do with stupidity had to be set aside. Not only were the features of incompetence extraordinarily similar from military disaster to military disaster, but the military itself tended to choose people with the same psychological flaws. It led soldiers over the top to disaster, or to a frozen death, as in the Crimea.

These characteristics included arrogant underestimation of the enemy, the inability to learn from experience, resistance to new technologies or new tactics, and an aversion to reconnaissance and intelligence.

Other common themes are great physical bravery but little moral courage, an imperviousness to human suffering, passivity and indecision, and a tendency to lay the blame on others. They tend to have a love of the frontal assault – nothing too clever – and of smartness, precision and the military pecking order.

Dixon also described a tendency to eschew moderate risks for tasks so difficult that failure might seem excusable.

Therein lies the great paradox. To be a successful military commander, you need more flexibility of thought and hierarchy than is encouraged by the traditional military – or the traditional Conservative party, as the xenophobes inch their way into the driving seat.

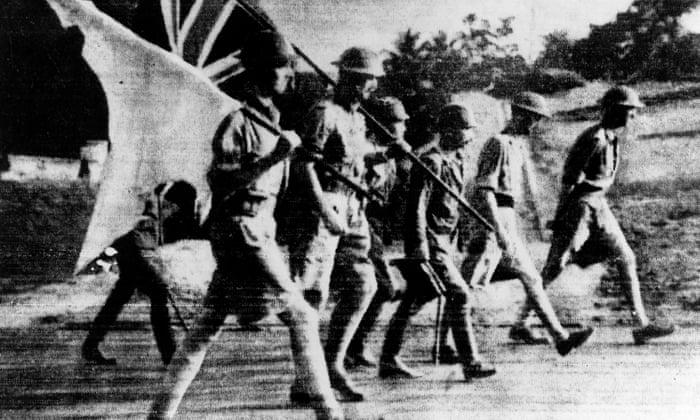

But it was Dixon’s description of the disastrous fall of Singapore in 1942, almost without a fight, because the local command distrusted new tactics and underestimated the Japanese, that really chimes. And his description of too many second-rate officers repeating how they wanted to “teach a lesson to the Japs”.

None of this suggests that Brexit is somehow the wrong strategy, but that the agenda has been wrested by a group of people showing the classic symptoms of the psychology of military incompetence, including a self-satisfied obsession with appearance over reality and pomp over practicality, and a serious tendency to talk about European nations as if they needed to be “taught a lesson”.

Never was imagination and a sophisticated understanding of a changing world so required. Read Dixon, and you begin to worry that the more we hear fighting talk as if the continent were filled with enemies, the more we might expect a hideous capitulation.

Dixon died in 2013, but he did leave behind this advice, originally given by Prince Philip to Sandhurst cadets in 1955: “As you grow older, try not to be afraid of new ideas. New or original ideas can be bad as well as good, but whereas an intelligent man with an open mind can demolish a bad idea by reasoned argument, those who allow their brains to atrophy resort to meaningless catchphrases, to derision and finally to anger in the face of anything new.” Right or wrong, it sounds like we need a few more Brexit mutineers.

A fascinating article by Simon Kuper has proposed a parallel between Brexit and the strange cargo cults of Melanesia, when societies suddenly destroy their economic underpinnings in search of a golden age, because they perceive the tribe is in some kind of decline.

It is particularly relevant now that corners of the Conservative party appear to be baying for a non-negotiated Brexit. And unfortunately, as the countdown ticks by, that may well be what they get.

There is another parallel, but it comes from psychology not anthropology. It derives from an influential theory by a former military engineer-turned-psychologist, Norman Dixon. His book, On the Psychology of Military Incompetence, was published in 1976, and has been in print ever since. His ideas may draw too much on Freudian concepts for current tastes, but there are worrying parallels to the phenomenon that he identified: the syndrome that seemed to lie behind so many British military disasters.

His thesis was that the old idea that military incompetence was something to do with stupidity had to be set aside. Not only were the features of incompetence extraordinarily similar from military disaster to military disaster, but the military itself tended to choose people with the same psychological flaws. It led soldiers over the top to disaster, or to a frozen death, as in the Crimea.

These characteristics included arrogant underestimation of the enemy, the inability to learn from experience, resistance to new technologies or new tactics, and an aversion to reconnaissance and intelligence.

Other common themes are great physical bravery but little moral courage, an imperviousness to human suffering, passivity and indecision, and a tendency to lay the blame on others. They tend to have a love of the frontal assault – nothing too clever – and of smartness, precision and the military pecking order.

Dixon also described a tendency to eschew moderate risks for tasks so difficult that failure might seem excusable.

Therein lies the great paradox. To be a successful military commander, you need more flexibility of thought and hierarchy than is encouraged by the traditional military – or the traditional Conservative party, as the xenophobes inch their way into the driving seat.

But it was Dixon’s description of the disastrous fall of Singapore in 1942, almost without a fight, because the local command distrusted new tactics and underestimated the Japanese, that really chimes. And his description of too many second-rate officers repeating how they wanted to “teach a lesson to the Japs”.

None of this suggests that Brexit is somehow the wrong strategy, but that the agenda has been wrested by a group of people showing the classic symptoms of the psychology of military incompetence, including a self-satisfied obsession with appearance over reality and pomp over practicality, and a serious tendency to talk about European nations as if they needed to be “taught a lesson”.

Never was imagination and a sophisticated understanding of a changing world so required. Read Dixon, and you begin to worry that the more we hear fighting talk as if the continent were filled with enemies, the more we might expect a hideous capitulation.

Dixon died in 2013, but he did leave behind this advice, originally given by Prince Philip to Sandhurst cadets in 1955: “As you grow older, try not to be afraid of new ideas. New or original ideas can be bad as well as good, but whereas an intelligent man with an open mind can demolish a bad idea by reasoned argument, those who allow their brains to atrophy resort to meaningless catchphrases, to derision and finally to anger in the face of anything new.” Right or wrong, it sounds like we need a few more Brexit mutineers.

Monday, 27 November 2017

The magical thinking that misleads managers

A handy guide to sorcery and superstitions in modern leadership

ANDREW HILL in the FT

It has been a while since a UK company was accused of sorcery.

ANDREW HILL in the FT

It has been a while since a UK company was accused of sorcery.

Congratulations, then, to evolutionary biologist Sally Le Page for triggering just such a charge last week. She blogged her astonishment that many of the country’s biggest water companies had blithely admitted to using dowsing rods to help locate pipes and leaks. Another scientist has dismissed the technique as witchcraft.

The water suppliers themselves have been rowing back fast. Some engineers were part-time diviners, apparently, but the real hard work of leak detection was backed by drones, robots and lots and lots of science.

I say let us allow the water industry’s warlocks to indulge their medieval pastimes. After all, there are plenty of examples of modern management and leadership based on superstition, credulity and blind faith. Here are just a few:

Numerology. In China, mumbo-jumbo about feng shui and ominous or propitious flotation dates, trading symbols and stock codes often influences how supposedly sophisticated companies arrange their affairs. Elements of Alibaba’s 2014 listing appeared to revolve around the “lucky” number eight, for example.

But before western chief executives scoff, they should consider how much they are still in thrall to the cult described in Alex Berenson’s 2003book The Number — the quarterly earnings consensus they conspire with analysts and investors to hit, or better still, to beat. Regular evidence — recently, for instance, from Campbell Soup (a miss), and Home Depot (a “beat”) — suggests the cult is thriving.

Indeed, the availability and crunchability of Big Data have broadened disciples of the number. They now include company bosses who worship near-term, data-driven answers, rather than holding out for better, if messier, longer-term solutions that take account of human intuition.

As the veteran management thinker Charles Handy pointed out in a rousing closing address to the recent Drucker Forum, “if the organisation were purely digitised . . . it would be a very dreary place, a prison for the human soul”.

Leaps of faith. Any chief executive who has ever announced a corporate vision without a clear idea of the kinds of steps needed to achieve the goal is at least partly guilty of magical thinking.

Richard Rumelt wrote in Good Strategy/Bad Strategy about the dangerous delusion that aiming for success can lead to success: “I would not care to fly in an aircraft designed by people who focused only on an image of a flying aeroplane and never considered modes of failure.”

Throw a coin and make a wish. Modern companies still close their eyes to evidence suggesting bonuses are at best a blunt incentive, and chuck cash at staff in the hope that it will help them reach their heart’s desire. At least wishing wells swallow the donation with no adverse consequence, other than the loss of your penny. Unfettered bonus culture, as the worst excesses of the financial crisis suggest, can backfire in unexpected ways.

Chants and mantras. Slavishly applied governance codes and regulations help box-ticking compliance staff and board members sleep easy, by absolving them of the need to make difficult judgments. Meaningless mission statements give executives a mantra to recite as cover for not actually putting their values into practice.

Human sacrifice. Restructurings and lay-offs are the modern ritual for appeasing the gods (but without the benefits of bringing the community together for a bit of a celebration).

Hero worship. For all the modish talk of flat hierarchies and distributed leadership, chief executives still become the central figures in a myth that is largely of their own creation.

The most dangerous part of this self-delusion is that they believe success was achieved entirely through their “skill, preparation and tenacity”, as described by Jim Collins and Morten Hansen in Great by Choice.

The researchers found successful leaders could generate a greater “return on luck” by being more disciplined at exploiting opportunities and riding bad luck to make themselves stronger. But they pointed out there was a fine line between the best leaders and those who put their organisations at risk through an exaggerated and dangerous belief in their own powers. Such leaders had a tendency to make these sorts of assertions: “Luck played no role in my success — I’m just really good.”

Here is where humble deference to unpredictable and poorly understood outside forces would be healthy. If nothing else, over-confident leaders should be reminded that their destiny is sometimes out of their hands.

Sunday, 26 November 2017

Saturday, 25 November 2017

Thursday, 23 November 2017

From inboxing to thought showers: how business bullshit took over

Andre Spicer in The Guardian

In early 1984, executives at the telephone company Pacific Bell made a fateful decision. For decades, the company had enjoyed a virtual monopoly on telephone services in California, but now it was facing a problem. The industry was about to be deregulated, and Pacific Bell would soon be facing tough competition.

The management team responded by doing all the things managers usually do: restructuring, downsizing, rebranding. But for the company executives, this wasn’t enough. They worried that Pacific Bell didn’t have the right culture, that employees did not understand “the profit concept” and were not sufficiently entrepreneurial. If they were to compete in this new world, it was not just their balance sheet that needed an overhaul, the executives decided. Their 23,000 employees needed to be overhauled as well.

The company turned to a well-known organisational development specialist, Charles Krone, who set about designing a management-training programme to transform the way people thought, talked and behaved. The programme was based on the ideas of the 20th-century Russian mystic George Gurdjieff. According to Gurdjieff, most of us spend our days mired in “waking sleep”, and it is only by shedding ingrained habits of thinking that we can liberate our inner potential. Gurdjieff’s mystical ideas originally appealed to members of the modernist avant garde, such as the writer Katherine Mansfield and the architect Frank Lloyd Wright. More than 60 years later, senior executives at Pacific Bell were likewise seduced by Gurdjieff’s ideas. The company planned to spend $147m (£111m) putting their employees through the new training programme, which came to be known as Kroning.

Over the course of 10 two-day sessions, staff were instructed in new concepts, such as “the law of three” (a “thinking framework that helps us identify the quality of mental energy we have”), and discovered the importance of “alignment”, “intentionality” and “end-state visions”. This new vocabulary was designed to awake employees from their bureaucratic doze and open their eyes to a new higher-level consciousness. And some did indeed feel like their ability to get things done had improved.

But there were some unfortunate side-effects of this heightened corporate consciousness. First, according to one former middle manager, it was virtually impossible for anyone outside the company to understand this new language the employees were speaking. Second, the manager said, the new language “led to a lot more meetings” and the sheer amount of time wasted nurturing their newfound states of higher consciousness meant that “everything took twice as long”. “If the energy that had been put into Kroning had been put to the business at hand, we all would have gotten a lot more done,” said the manager.

Although Kroning was packaged in the new-age language of psychic liberation, it was backed by all the threats of an authoritarian corporation. Many employees felt they were under undue pressure to buy into Kroning. For instance, one manager was summoned to her superior’s office after a team member walked out of a Kroning session. She was asked to “force out or retire” the rebellious employee.

Some Pacific Bell employees wrote to their congressmen about Kroning. Newspapers ran damning stories with headlines such as “Phone company dabbles in mysticism”. The Californian utility regulator launched a public inquiry, and eventually closed the training course, but not before $40m dollars had been spent.

During this period, a young computer programmer at Pacific Bell was spending his spare time drawing a cartoon that mercilessly mocked the management-speak that had invaded his workplace. The cartoon featured a hapless office drone, his disaffected colleagues, his evil boss and an even more evil management consultant. It was a hit, and the comic strip was syndicated in newspapers across the world. The programmer’s name was Scott Adams, and the series he created was Dilbert. You can still find these images pinned up in thousands of office cubicles around the world today.

Although Kroning may have been killed off, Kronese has lived on. The indecipherable management-speak of which Charles Krone was an early proponent seems to have infected the entire world. These days, Krone’s gobbledygook seems relatively benign compared to much of the vacuous language circulating in the emails and meeting rooms of corporations, government agencies and NGOs. Words like “intentionality” sound quite sensible when compared to “ideation”, “imagineering”, and “inboxing” – the sort of management-speak used to talk about everything from educating children to running nuclear power plants. This language has become a kind of organisational lingua franca, used by middle managers in the same way that freemasons use secret handshakes – to indicate their membership and status. It echoes across the cubicled landscape. It seems to be everywhere, and refer to anything, and nothing.

It hasn’t always been this way. A certain amount of empty talk is unavoidable when humans gather together in large groups, but the kind of bullshit through which we all have to wade every day is a remarkably recent creation. To understand why, we have to look at how management fashions have changed over the past century or so.

In the late 18th century, firms were owned and operated by businesspeople who tended to rely on tradition and instinct to manage their employees. Over the next century, as factories became more common, a new figure appeared: the manager. This new class of boss faced a big problem, albeit one familiar to many people who occupy new positions: they were not taken seriously. To gain respect, managers assumed the trappings of established professions such as doctors and lawyers. They were particularly keen to be seen as a new kind of engineer, so they appropriated the stopwatches and rulers used by them. In the process, they created the first major workplace fashion: scientific management.

Charlie Chaplin ‘satirising the cult of scientific management’ in 1936 film Modern Times. Photograph: Allstar/Cinetext

Charlie Chaplin ‘satirising the cult of scientific management’ in 1936 film Modern Times. Photograph: Allstar/Cinetext

Firms started recruiting efficiency experts to conduct time-and-motion studies. After recording every single movement of a worker in minute detail, the time-and-motion expert would rearrange the worker’s performance of tasks into a more efficient order. Their aim was to make the worker into a well-functioning machine, doing each part of the job in the most efficient way. Scientific management was not limited to the workplaces of the capitalist west – Stalin pushed for similar techniques to be imposed in factories throughout the Soviet Union.

Workers found the new techniques alien, and a backlash inevitably followed. Charlie Chaplin famously satirised the cult of scientific management in his 1936 film Modern Times, which depicts a factory worker who is slowly driven mad by the pressures of life on the production line.

As scientific management became increasingly unpopular, executives began casting around for alternatives. They found inspiration in a famous series of experiments conducted by psychologists in the 1920s at the Hawthorne Works, a factory complex in Illinois where tens of thousands of workers were employed by Western Electric to make telephone equipment. A team of researchers from Harvard had initially set out to discover whether changes in environment, such as adjusting the lighting or temperature, could influence how much workers produced each day.

To their surprise, the researchers found that no matter how light or dark the workplace was, employees continued to work hard. The only thing that seemed to make a difference was the amount of attention that workers got from the experimenters. This insight led one of the researchers, an Australian psychologist called Elton Mayo, to conclude that what he called the “human aspects” of work were far more important than “environmental” factors. While this may seem obvious, it came as news to many executives at the time.

As Mayo’s ideas caught hold, companies attempted to humanise their workplaces. They began talking about human relationships, worker motivation and group dynamics. They started conducting personality testing and running teambuilding exercises: all in the hope of nurturing good human relations in the workplace.

This newfound interest in the human side of work did not last long. During the second world war, as the US and UK military invested heavily in trying to make war more efficient, management fashions began to shift. A bright young Berkeley graduate called Robert McNamara led a US army air forces team that used statistics to plan the most cost-effective way to flatten Japan in bombing campaigns. After the war, many military leaders brought these new techniques into the corporate world. McNamara, for instance, joined the Ford Motor Company, rising quickly to become its CEO, while the mathematical procedures that he had developed during the war were enthusiastically taken up by companies to help plan the best way to deliver cheese, toothpaste and Barbie dolls to American consumers. Today these techniques are known as supply-chain management.

During the postwar years, the individual worker once again became a cog in a large, hierarchical machine. While many of the grey-suited employees at these firms savoured the security, freedom and increasing affluence that their work brought, many also complained about the deep lack of meaning in their lives. The backlash came in the late 1960s, as the youth movement railed against the conformity demanded by big corporations. Protesters sprayed slogans such as “live without dead time” and “to hell with boundaries” on to city walls around the world. They wanted to be themselves, express who they really were, and not have to obey “the Man”.

In response to this cultural change, in the 1970s, management fashions changed again. Executives began attending new-age workshops to help them “self actualise” by unlocking their hidden “human potential”. Companies instigated “encounter groups”, in which employees could explore their deeper inner emotions. Offices were redesigned to look more like university campuses than factories.

Mad Men’s liberated adman Don Draper (Jon Hamm). Photograph: Courtesy of AMC/AMC

Mad Men’s liberated adman Don Draper (Jon Hamm). Photograph: Courtesy of AMC/AMC

Nowhere is this shift better captured than in the final episode of the television series Mad Men. Don Draper had been the exemplar of the organisational man, wearing a standard-issue grey suit when we met him at the beginning of the show’s first series. After suffering numerous breakdowns over the intervening years, he finds himself at the Esalen institute in northern California, the home of the human potential movement. Initially, Draper resists. But soon he is sitting in a confessional circle, sobbing as he tells his story. His personal breakthrough leads him to take up meditating and chanting, looking out over the Pacific Ocean. The result of Don Draper’s visit to Esalen isn’t just personal transformation. The final scene shows the now-liberated adman’s new creation – an iconic Coca-Cola commercial in which a multiracial group of children stand on a hilltop singing about how they would like to buy the world a Coke and drink it in perfect harmony.

After the fictional Don Draper visited Esalen, work became a place you could go to find yourself. Corporate mission statements now sounded like the revolutionary graffiti of the 1960s. The company training programme run by Charles Krone at Pacific Bell came straight from the Esalen playbook.

Since new-age ideas first permeated the workplace in the 1970s, the spin cycle of management-speak has sped up. During the 1980s, management experts went in search of fresh ideas in Japan. Management became a kind of martial art, with executives visiting “quality dojos” to earn “lean black-belts”. In their 1982 bestseller, In Search of Excellence, Tom Peters and Robert Waterman – both employees of McKinsey, the huge management consultancy agency – recommended that firms foster the same commitment to the company that they found among Honda employees in Japan. The book included the story of one Japanese employee who happens upon a damaged Honda on a public street. He stops and immediately begins repairing the car. The reason? He can’t bear to see a Honda that isn’t perfect.

While McKinsey consultants were mining the wisdom of the east, the ideas of Harvard Business School’s Michael Jensen started to find favour among Wall Street financiers. Jensen saw the corporation as a portfolio of assets. Even people – labelled as “human resources” – were part of this portfolio. Each company existed to create returns for shareholders, and if managers failed to do this, they should be fired. If a company didn’t generate adequate returns, it should be broken up and sold off. Every little part of the company was seen as a business. Seduced by this view, many organisations started creating “internal markets”. In the 1990s, under director general John Birt, the BBC created a system in which everything from time in a recording studio to toilet cleaning was traded on a complex internal market. The number of accountants working for the broadcaster exploded, while people who created TV and radio shows were laid off.

As companies have become increasingly ravenous for the latest management fad, they have also become less discerning. Some bizarre recent trends include equine-assisted coaching (“You can lead people, but can you lead a horse?”) and rage rooms (a room where employees can go to take out their frustrations by smashing up office furniture, computers and images of their boss).

A century of management fads has created workplaces that are full of empty words and equally empty rituals. We have to live with the consequences of this history every day. Consider a meeting I recently attended. During the course of an hour, I recorded 64 different nuggets of corporate claptrap. They included familiar favourites such as “doing a deep dive”, “reaching out”, and “thought leadership”. There were also some new ones I hadn’t heard before: people with “protected characteristics” (anyone who wasn’t a white straight guy), “the aha effect” (realising something), “getting our friends in the tent” (getting support from others).

After the meeting, I found myself wondering why otherwise smart people so easily slipped into this kind of business bullshit. How had this obfuscatory way of speaking become so successful? There are a number of familiar and credible explanations. People use management-speak to give the impression of expertise. The inherent vagueness of this language also helps us dodge tough questions. Then there is the simple fact that even if business bullshit annoys many people, in most work situations we try our hardest to be polite and avoid confrontation. So instead of causing a scene by questioning the bullshit flying around the room, I followed the example of Simon Harwood, the director of strategic governance in the BBC’s self-satirising TV sitcom W1A. I used his standard response to any idea – no matter how absurd – “hurrah”.

Still, these explanations did not seem to fully account for the conquest of bullshit. I came across one further explanation in a short article by the anthropologist David Graeber. As factories producing goods in the west have been dismantled, and their work outsourced or replaced with automation, large parts of western economies have been left with little to do. In the 1970s, some sociologists worried that this would lead to a world in which people would need to find new ways to fill their time. The great tragedy for many is that just the opposite seems to have happened.

Simon Harwood (Jason Watkins, centre) of W1A, the BBC’s fictional director of strategic governance. Photograph: Jack Barnes/BBC

Simon Harwood (Jason Watkins, centre) of W1A, the BBC’s fictional director of strategic governance. Photograph: Jack Barnes/BBC

At the very point when work seemed to be withering away, we all became obsessed with it. To be a good citizen, you need to be a productive citizen. There is only one problem, of course: there is less than ever that actually needs to be produced. As Graeber pointed out, the answer has come in the form of what he calls “bullshit jobs”. These are jobs in which people experience their work as “utterly meaningless, contributing nothing to the world”. In a YouGov poll conducted in 2015, 37% of respondents in the UK said their job made no meaningful contribution to the world. But people working in bullshit jobs need to do something. And that something is usually the production, distribution and consumption of bullshit. According to a 2014 survey by the polling agency Harris, the average US employee now spends 45% of their working day doing their real job. The other 55% is spent doing things such as wading through endless emails or attending pointless meetings. Many employees have extended their working day so they can stay late to do their “real work”.

One thing continued to puzzle me: why was it that so many people were paid to do this kind of empty work. One reason that David Graeber gives, in his book The Utopia of Rules, is rampant bureaucracy: there are more forms to be filled in, procedures to be followed and standards to be complied with than ever. Today, bureaucracy comes cloaked in the language of change. Organisations are full of people whose job is to create change for no real reason.

Manufacturing hollow change requires a constant supply of new management fads and fashions. Fortunately, there is a massive industry of business bullshit merchants who are quite happy to supply it. For each new change, new bullshit is needed. Looking back over the list of business bullshit I had noted down during the meeting, I realised that much of it was directly related to empty new bureaucratic initiatives, which were seen as terribly urgent, but would probably be forgotten about in a few years’ time.

One of the corrosive effects of business bullshit can be seen in the statistic that 43% of all teachers in England are considering quitting in the next five years. The most frequently cited reasons are increasingly heavy workloads caused by excessive administration, and a lack of time and space to devote to educating students. A remarkably similar picture appears if you look at the healthcare sector: in the UK, 81% of senior doctors say they are considering retiring from their job early; 57% of GPs are considering leaving the profession; 66% of nurses say they would quit if they could. In each case, the most frequently cited reason is stress caused by increasing managerial demands, and lack of time to do their job properly.

It is not just employees who feel overwhelmed. During the 1980s, when Kroning was in full swing, empty management-speak was confined to the beige meeting rooms of large corporations. Now, it has seeped into every aspect of life. Politicians use business balderdash to avoid grappling with important issues. The machinery of state has also come down with the word-virus. The NHS is crawling with “quality sensei”, “lean ninjas”, and “blue-sky thinkers”. Even schools are flooded with the latest business buzzwords like “grit”, “flipped learning” and “mastery”. Naturally, the kids are learning fast. One teacher recalled how a seven-year-old described her day at school: “Well, when we get to class, we get out our books and start on our non-negotiables.”

In the introduction to his 2015 book, Trust Me, PR Is Dead, the former PR executive Robert Phillips tells a fascinating story. One day he was called up by the CEO of a global corporation. The CEO was worried. A factory which was part of his firm’s supply chain had caught fire and 100 women had burned to death. “My chairman’s been giving me grief,” said the CEO. “He thinks we’re failing to get our message across. We are not emphasising our CSR [corporate social responsibility] credentials well enough.” Phillips responded: “While 100 women’s bodies are still smouldering?” The CEO was “struggling to contain both incredulity and temper”. “I know,” he said. “Please help.” Phillips responded: “You start with actions, not words.”

In many ways, this one interaction tells us how bullshit is used in corporate life. Individual executives facing a problem know that turning to bullshit is probably not the best idea. However, they feel compelled. The problem is that such compulsions often cloud people’s best judgements. They start to think empty words will trump reasonable reflection and considered action. Sadly, in many contexts, empty words win out.

If we hope to improve organisational life – and the wider impact that organisations have on our society – then a good place to start is by reducing the amount of bullshit our organisations produce. Business bullshit allows us to blather on without saying anything. It empties out language and makes us less able to think clearly and soberly about the real issues. As we find our words become increasingly meaningless, we begin to feel a sense of powerlessness. We start to feel there is little we can do apart from play along, benefit from the game and have the occasional laugh.

But this does not need to be the case. Business bullshit can and should be challenged. This is a task each of us can take up by refusing to use empty management-speak. We can stop ourselves from being one more conduit in its circulation. Instead of just rolling our eyes and checking our emails, we should demand something more meaningful.

Clearly, our own individual efforts are not enough. Putting management-speak in its place is going to require a collective effort. What we need is an anti-bullshit movement. It would be made up of people from all walks of life who are dedicated to rooting out empty language. It would question management twaddle in government, in popular culture, in the private sector, in education and in our private lives.

The aim would not just be bullshit-spotting. It would also be a way of reminding people that each of our institutions has its own language and rich set of traditions which are being undermined by the spread of the empty management-speak. It would try to remind people of the power which speech and ideas can have when they are not suffocated with bullshit. By cleaning out the bullshit, it might become possible to have much better functioning organisations and institutions and richer and fulfilling lives.

In early 1984, executives at the telephone company Pacific Bell made a fateful decision. For decades, the company had enjoyed a virtual monopoly on telephone services in California, but now it was facing a problem. The industry was about to be deregulated, and Pacific Bell would soon be facing tough competition.

The management team responded by doing all the things managers usually do: restructuring, downsizing, rebranding. But for the company executives, this wasn’t enough. They worried that Pacific Bell didn’t have the right culture, that employees did not understand “the profit concept” and were not sufficiently entrepreneurial. If they were to compete in this new world, it was not just their balance sheet that needed an overhaul, the executives decided. Their 23,000 employees needed to be overhauled as well.

The company turned to a well-known organisational development specialist, Charles Krone, who set about designing a management-training programme to transform the way people thought, talked and behaved. The programme was based on the ideas of the 20th-century Russian mystic George Gurdjieff. According to Gurdjieff, most of us spend our days mired in “waking sleep”, and it is only by shedding ingrained habits of thinking that we can liberate our inner potential. Gurdjieff’s mystical ideas originally appealed to members of the modernist avant garde, such as the writer Katherine Mansfield and the architect Frank Lloyd Wright. More than 60 years later, senior executives at Pacific Bell were likewise seduced by Gurdjieff’s ideas. The company planned to spend $147m (£111m) putting their employees through the new training programme, which came to be known as Kroning.

Over the course of 10 two-day sessions, staff were instructed in new concepts, such as “the law of three” (a “thinking framework that helps us identify the quality of mental energy we have”), and discovered the importance of “alignment”, “intentionality” and “end-state visions”. This new vocabulary was designed to awake employees from their bureaucratic doze and open their eyes to a new higher-level consciousness. And some did indeed feel like their ability to get things done had improved.

But there were some unfortunate side-effects of this heightened corporate consciousness. First, according to one former middle manager, it was virtually impossible for anyone outside the company to understand this new language the employees were speaking. Second, the manager said, the new language “led to a lot more meetings” and the sheer amount of time wasted nurturing their newfound states of higher consciousness meant that “everything took twice as long”. “If the energy that had been put into Kroning had been put to the business at hand, we all would have gotten a lot more done,” said the manager.

Although Kroning was packaged in the new-age language of psychic liberation, it was backed by all the threats of an authoritarian corporation. Many employees felt they were under undue pressure to buy into Kroning. For instance, one manager was summoned to her superior’s office after a team member walked out of a Kroning session. She was asked to “force out or retire” the rebellious employee.

Some Pacific Bell employees wrote to their congressmen about Kroning. Newspapers ran damning stories with headlines such as “Phone company dabbles in mysticism”. The Californian utility regulator launched a public inquiry, and eventually closed the training course, but not before $40m dollars had been spent.

During this period, a young computer programmer at Pacific Bell was spending his spare time drawing a cartoon that mercilessly mocked the management-speak that had invaded his workplace. The cartoon featured a hapless office drone, his disaffected colleagues, his evil boss and an even more evil management consultant. It was a hit, and the comic strip was syndicated in newspapers across the world. The programmer’s name was Scott Adams, and the series he created was Dilbert. You can still find these images pinned up in thousands of office cubicles around the world today.

Although Kroning may have been killed off, Kronese has lived on. The indecipherable management-speak of which Charles Krone was an early proponent seems to have infected the entire world. These days, Krone’s gobbledygook seems relatively benign compared to much of the vacuous language circulating in the emails and meeting rooms of corporations, government agencies and NGOs. Words like “intentionality” sound quite sensible when compared to “ideation”, “imagineering”, and “inboxing” – the sort of management-speak used to talk about everything from educating children to running nuclear power plants. This language has become a kind of organisational lingua franca, used by middle managers in the same way that freemasons use secret handshakes – to indicate their membership and status. It echoes across the cubicled landscape. It seems to be everywhere, and refer to anything, and nothing.

It hasn’t always been this way. A certain amount of empty talk is unavoidable when humans gather together in large groups, but the kind of bullshit through which we all have to wade every day is a remarkably recent creation. To understand why, we have to look at how management fashions have changed over the past century or so.

In the late 18th century, firms were owned and operated by businesspeople who tended to rely on tradition and instinct to manage their employees. Over the next century, as factories became more common, a new figure appeared: the manager. This new class of boss faced a big problem, albeit one familiar to many people who occupy new positions: they were not taken seriously. To gain respect, managers assumed the trappings of established professions such as doctors and lawyers. They were particularly keen to be seen as a new kind of engineer, so they appropriated the stopwatches and rulers used by them. In the process, they created the first major workplace fashion: scientific management.

Charlie Chaplin ‘satirising the cult of scientific management’ in 1936 film Modern Times. Photograph: Allstar/Cinetext

Charlie Chaplin ‘satirising the cult of scientific management’ in 1936 film Modern Times. Photograph: Allstar/CinetextFirms started recruiting efficiency experts to conduct time-and-motion studies. After recording every single movement of a worker in minute detail, the time-and-motion expert would rearrange the worker’s performance of tasks into a more efficient order. Their aim was to make the worker into a well-functioning machine, doing each part of the job in the most efficient way. Scientific management was not limited to the workplaces of the capitalist west – Stalin pushed for similar techniques to be imposed in factories throughout the Soviet Union.

Workers found the new techniques alien, and a backlash inevitably followed. Charlie Chaplin famously satirised the cult of scientific management in his 1936 film Modern Times, which depicts a factory worker who is slowly driven mad by the pressures of life on the production line.

As scientific management became increasingly unpopular, executives began casting around for alternatives. They found inspiration in a famous series of experiments conducted by psychologists in the 1920s at the Hawthorne Works, a factory complex in Illinois where tens of thousands of workers were employed by Western Electric to make telephone equipment. A team of researchers from Harvard had initially set out to discover whether changes in environment, such as adjusting the lighting or temperature, could influence how much workers produced each day.

To their surprise, the researchers found that no matter how light or dark the workplace was, employees continued to work hard. The only thing that seemed to make a difference was the amount of attention that workers got from the experimenters. This insight led one of the researchers, an Australian psychologist called Elton Mayo, to conclude that what he called the “human aspects” of work were far more important than “environmental” factors. While this may seem obvious, it came as news to many executives at the time.

As Mayo’s ideas caught hold, companies attempted to humanise their workplaces. They began talking about human relationships, worker motivation and group dynamics. They started conducting personality testing and running teambuilding exercises: all in the hope of nurturing good human relations in the workplace.

This newfound interest in the human side of work did not last long. During the second world war, as the US and UK military invested heavily in trying to make war more efficient, management fashions began to shift. A bright young Berkeley graduate called Robert McNamara led a US army air forces team that used statistics to plan the most cost-effective way to flatten Japan in bombing campaigns. After the war, many military leaders brought these new techniques into the corporate world. McNamara, for instance, joined the Ford Motor Company, rising quickly to become its CEO, while the mathematical procedures that he had developed during the war were enthusiastically taken up by companies to help plan the best way to deliver cheese, toothpaste and Barbie dolls to American consumers. Today these techniques are known as supply-chain management.

During the postwar years, the individual worker once again became a cog in a large, hierarchical machine. While many of the grey-suited employees at these firms savoured the security, freedom and increasing affluence that their work brought, many also complained about the deep lack of meaning in their lives. The backlash came in the late 1960s, as the youth movement railed against the conformity demanded by big corporations. Protesters sprayed slogans such as “live without dead time” and “to hell with boundaries” on to city walls around the world. They wanted to be themselves, express who they really were, and not have to obey “the Man”.

In response to this cultural change, in the 1970s, management fashions changed again. Executives began attending new-age workshops to help them “self actualise” by unlocking their hidden “human potential”. Companies instigated “encounter groups”, in which employees could explore their deeper inner emotions. Offices were redesigned to look more like university campuses than factories.

Mad Men’s liberated adman Don Draper (Jon Hamm). Photograph: Courtesy of AMC/AMC

Mad Men’s liberated adman Don Draper (Jon Hamm). Photograph: Courtesy of AMC/AMCNowhere is this shift better captured than in the final episode of the television series Mad Men. Don Draper had been the exemplar of the organisational man, wearing a standard-issue grey suit when we met him at the beginning of the show’s first series. After suffering numerous breakdowns over the intervening years, he finds himself at the Esalen institute in northern California, the home of the human potential movement. Initially, Draper resists. But soon he is sitting in a confessional circle, sobbing as he tells his story. His personal breakthrough leads him to take up meditating and chanting, looking out over the Pacific Ocean. The result of Don Draper’s visit to Esalen isn’t just personal transformation. The final scene shows the now-liberated adman’s new creation – an iconic Coca-Cola commercial in which a multiracial group of children stand on a hilltop singing about how they would like to buy the world a Coke and drink it in perfect harmony.

After the fictional Don Draper visited Esalen, work became a place you could go to find yourself. Corporate mission statements now sounded like the revolutionary graffiti of the 1960s. The company training programme run by Charles Krone at Pacific Bell came straight from the Esalen playbook.

Since new-age ideas first permeated the workplace in the 1970s, the spin cycle of management-speak has sped up. During the 1980s, management experts went in search of fresh ideas in Japan. Management became a kind of martial art, with executives visiting “quality dojos” to earn “lean black-belts”. In their 1982 bestseller, In Search of Excellence, Tom Peters and Robert Waterman – both employees of McKinsey, the huge management consultancy agency – recommended that firms foster the same commitment to the company that they found among Honda employees in Japan. The book included the story of one Japanese employee who happens upon a damaged Honda on a public street. He stops and immediately begins repairing the car. The reason? He can’t bear to see a Honda that isn’t perfect.

While McKinsey consultants were mining the wisdom of the east, the ideas of Harvard Business School’s Michael Jensen started to find favour among Wall Street financiers. Jensen saw the corporation as a portfolio of assets. Even people – labelled as “human resources” – were part of this portfolio. Each company existed to create returns for shareholders, and if managers failed to do this, they should be fired. If a company didn’t generate adequate returns, it should be broken up and sold off. Every little part of the company was seen as a business. Seduced by this view, many organisations started creating “internal markets”. In the 1990s, under director general John Birt, the BBC created a system in which everything from time in a recording studio to toilet cleaning was traded on a complex internal market. The number of accountants working for the broadcaster exploded, while people who created TV and radio shows were laid off.

As companies have become increasingly ravenous for the latest management fad, they have also become less discerning. Some bizarre recent trends include equine-assisted coaching (“You can lead people, but can you lead a horse?”) and rage rooms (a room where employees can go to take out their frustrations by smashing up office furniture, computers and images of their boss).

A century of management fads has created workplaces that are full of empty words and equally empty rituals. We have to live with the consequences of this history every day. Consider a meeting I recently attended. During the course of an hour, I recorded 64 different nuggets of corporate claptrap. They included familiar favourites such as “doing a deep dive”, “reaching out”, and “thought leadership”. There were also some new ones I hadn’t heard before: people with “protected characteristics” (anyone who wasn’t a white straight guy), “the aha effect” (realising something), “getting our friends in the tent” (getting support from others).

After the meeting, I found myself wondering why otherwise smart people so easily slipped into this kind of business bullshit. How had this obfuscatory way of speaking become so successful? There are a number of familiar and credible explanations. People use management-speak to give the impression of expertise. The inherent vagueness of this language also helps us dodge tough questions. Then there is the simple fact that even if business bullshit annoys many people, in most work situations we try our hardest to be polite and avoid confrontation. So instead of causing a scene by questioning the bullshit flying around the room, I followed the example of Simon Harwood, the director of strategic governance in the BBC’s self-satirising TV sitcom W1A. I used his standard response to any idea – no matter how absurd – “hurrah”.

Still, these explanations did not seem to fully account for the conquest of bullshit. I came across one further explanation in a short article by the anthropologist David Graeber. As factories producing goods in the west have been dismantled, and their work outsourced or replaced with automation, large parts of western economies have been left with little to do. In the 1970s, some sociologists worried that this would lead to a world in which people would need to find new ways to fill their time. The great tragedy for many is that just the opposite seems to have happened.

Simon Harwood (Jason Watkins, centre) of W1A, the BBC’s fictional director of strategic governance. Photograph: Jack Barnes/BBC

Simon Harwood (Jason Watkins, centre) of W1A, the BBC’s fictional director of strategic governance. Photograph: Jack Barnes/BBCAt the very point when work seemed to be withering away, we all became obsessed with it. To be a good citizen, you need to be a productive citizen. There is only one problem, of course: there is less than ever that actually needs to be produced. As Graeber pointed out, the answer has come in the form of what he calls “bullshit jobs”. These are jobs in which people experience their work as “utterly meaningless, contributing nothing to the world”. In a YouGov poll conducted in 2015, 37% of respondents in the UK said their job made no meaningful contribution to the world. But people working in bullshit jobs need to do something. And that something is usually the production, distribution and consumption of bullshit. According to a 2014 survey by the polling agency Harris, the average US employee now spends 45% of their working day doing their real job. The other 55% is spent doing things such as wading through endless emails or attending pointless meetings. Many employees have extended their working day so they can stay late to do their “real work”.

One thing continued to puzzle me: why was it that so many people were paid to do this kind of empty work. One reason that David Graeber gives, in his book The Utopia of Rules, is rampant bureaucracy: there are more forms to be filled in, procedures to be followed and standards to be complied with than ever. Today, bureaucracy comes cloaked in the language of change. Organisations are full of people whose job is to create change for no real reason.

Manufacturing hollow change requires a constant supply of new management fads and fashions. Fortunately, there is a massive industry of business bullshit merchants who are quite happy to supply it. For each new change, new bullshit is needed. Looking back over the list of business bullshit I had noted down during the meeting, I realised that much of it was directly related to empty new bureaucratic initiatives, which were seen as terribly urgent, but would probably be forgotten about in a few years’ time.

One of the corrosive effects of business bullshit can be seen in the statistic that 43% of all teachers in England are considering quitting in the next five years. The most frequently cited reasons are increasingly heavy workloads caused by excessive administration, and a lack of time and space to devote to educating students. A remarkably similar picture appears if you look at the healthcare sector: in the UK, 81% of senior doctors say they are considering retiring from their job early; 57% of GPs are considering leaving the profession; 66% of nurses say they would quit if they could. In each case, the most frequently cited reason is stress caused by increasing managerial demands, and lack of time to do their job properly.

It is not just employees who feel overwhelmed. During the 1980s, when Kroning was in full swing, empty management-speak was confined to the beige meeting rooms of large corporations. Now, it has seeped into every aspect of life. Politicians use business balderdash to avoid grappling with important issues. The machinery of state has also come down with the word-virus. The NHS is crawling with “quality sensei”, “lean ninjas”, and “blue-sky thinkers”. Even schools are flooded with the latest business buzzwords like “grit”, “flipped learning” and “mastery”. Naturally, the kids are learning fast. One teacher recalled how a seven-year-old described her day at school: “Well, when we get to class, we get out our books and start on our non-negotiables.”

In the introduction to his 2015 book, Trust Me, PR Is Dead, the former PR executive Robert Phillips tells a fascinating story. One day he was called up by the CEO of a global corporation. The CEO was worried. A factory which was part of his firm’s supply chain had caught fire and 100 women had burned to death. “My chairman’s been giving me grief,” said the CEO. “He thinks we’re failing to get our message across. We are not emphasising our CSR [corporate social responsibility] credentials well enough.” Phillips responded: “While 100 women’s bodies are still smouldering?” The CEO was “struggling to contain both incredulity and temper”. “I know,” he said. “Please help.” Phillips responded: “You start with actions, not words.”

In many ways, this one interaction tells us how bullshit is used in corporate life. Individual executives facing a problem know that turning to bullshit is probably not the best idea. However, they feel compelled. The problem is that such compulsions often cloud people’s best judgements. They start to think empty words will trump reasonable reflection and considered action. Sadly, in many contexts, empty words win out.

If we hope to improve organisational life – and the wider impact that organisations have on our society – then a good place to start is by reducing the amount of bullshit our organisations produce. Business bullshit allows us to blather on without saying anything. It empties out language and makes us less able to think clearly and soberly about the real issues. As we find our words become increasingly meaningless, we begin to feel a sense of powerlessness. We start to feel there is little we can do apart from play along, benefit from the game and have the occasional laugh.

But this does not need to be the case. Business bullshit can and should be challenged. This is a task each of us can take up by refusing to use empty management-speak. We can stop ourselves from being one more conduit in its circulation. Instead of just rolling our eyes and checking our emails, we should demand something more meaningful.

Clearly, our own individual efforts are not enough. Putting management-speak in its place is going to require a collective effort. What we need is an anti-bullshit movement. It would be made up of people from all walks of life who are dedicated to rooting out empty language. It would question management twaddle in government, in popular culture, in the private sector, in education and in our private lives.

The aim would not just be bullshit-spotting. It would also be a way of reminding people that each of our institutions has its own language and rich set of traditions which are being undermined by the spread of the empty management-speak. It would try to remind people of the power which speech and ideas can have when they are not suffocated with bullshit. By cleaning out the bullshit, it might become possible to have much better functioning organisations and institutions and richer and fulfilling lives.

Monday, 20 November 2017

The rise of dynamic and personalised pricing

Tim Walker in The Guardian

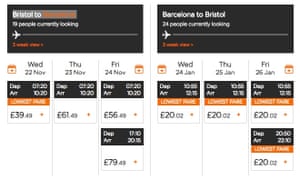

You wait 24 hours to book that flight, only to find it’s gone up by £100. You wait until Black Friday to buy that leather jacket and, sure enough, it’s been marked down. Today’s consumers are getting comfortable with the idea that prices online can fluctuate, not just at sale time, but several times over the course of a single day. Anyone who has booked a holiday on the internet is familiar with the concept, if not with its name. It’s known as dynamic pricing: when the cost of goods or services ebbs and flows in response to the slightest shifts in supply and demand, be it fresh croissants in the morning, a bargain TV or an Uber during a late-night “surge”.

Sports teams, entertainment venues and theme parks have started to use dynamic pricing methods, too, taking their cues from airlines and hotels to calibrate a range of ticketing deals that ensure they fill as many seats as possible. Last month, Regal, the US cinema chain, announced it would trial a form of dynamic ticket pricing at many of its multiplexes in 2018, in the hope of boosting its box office revenue. Digonex, one of the leading dynamic ticketing firms in the US, has consulted for Derby County and Manchester City football clubs in the UK. “In five years, dynamic pricing will be common practice in the attractions space,” says the company’s CEO, Greg Loewen. “The same goes for many other industries: movies, parking, tour operators.” Amazon, the world’s largest online retailer, tweaks countless prices every day. Savvy shoppers have learned to wait for bargains with the help of other sites such as CamelCamelCamel.com, which analyses Amazon price drops and lists the biggest. On a single day on Amazon.co.uk last week, those included a Samsung Galaxy S7 phone, down 14% from £510.29 to £439, and a pack of six 300g jars of Ovaltine, down 33% from £17.94 to £12.

Physical retailers can’t match the agility of their online rivals, not least because changing prices requires altering labels. But “smart shelves” – already common in European supermarkets – are coming to the UK, with digital price displays that allow retailers to offer deals at different times of day, along with information about the products. Sainsbury’s, Morrisons and Tesco have all trialled electronic pricing systems in select stores. Marks & Spencer conducted an electronic pricing experiment last year, selling sandwiches more cheaply during the morning rush hour to encourage commuters to buy their lunch early.