Between the relentless demands of corporate leaders and the capacity of the underclass to match the state’s violence, India needs a vision for itself that is morally defensible.

In the first week of 2011, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh allowed himself to be persuaded to accept N.R. Narayana Murthy’s invitation to travel to Mumbai to preside over a function to give away the Infosys Social Science Prizes. The Prime Minister even agreed to attend a dinner that Mr. Murthy wanted to host in his honour after the function at the Taj Mahal Hotel. So far so good. A few days before the event, there was a massive behind-the-scenes dust up between the Prime Minister’s staff and Mr. Murthy. The rub was that Mr. Murthy thought that since he was paying for the dinner, he had a right to dictate not only the guest list but even the seating arrangement. However, there is something called protocol and the dignity of constitutional offices. If the Governor and the Chief Minister of Maharashtra were to be at the dinner, they had to necessarily be seated on either side of the Prime Minister, whereas the host thought he ought to be sitting next to Dr. Singh. Mr. Murthy, however, was not one to be so easily rebuffed. As soon as the first course was served, he sought to convert the evening into a grand intellectual conversation and proceeded to invite his son to open the bowling. And the young son wanted to know from the Prime Minister what the government proposed to do so that young men like him could come back to India.

All this is recalled because the young man is now back in India, as executive assistant to his father, who in turn has allowed himself to be persuaded to take charge of Infosys again. Nepotism, did you say? No; no sir. A private company is free to hire anyone. Fair enough, but not exactly.

Mr. Murthy is not just a private businessman, minding his own business. He has often sought to inject himself into the public domain, telling a thing or two to the political class about how to behave. He has been serenaded as an “iconic” entrepreneur. During the heyday of civil society triumphalism two years ago, there was even a suggestion that Mr. Murthy be made President of India. That was the time when India’s corporate leaders thought they had the ethical credentials to write open letters to the Prime Minister and preach virtues of good governance.

Also read 1. Just how corrupt is Britain

2. Prices, Profits and Markets

3. Dantewada and the Maoists

Also read 1. Just how corrupt is Britain

2. Prices, Profits and Markets

3. Dantewada and the Maoists

Like other corporate leaders, the Murthys, father and son, represent an unrepentant ideological approach to the Indian state, its morals, manners and policies and purpose, but they are not the only ones to do so. The Maoists — who once again made their presence felt last month when they massacred the Congress top political leadership in Chhattisgarh — too have a list of ideological claims of their own on the Indian state. Both groups are relentless; both are unforgiving.

The May 25 attack was the boldest ideological challenge that the Maoists have posed to the country’s political leadership. Violence makes a demand on all stakeholders. It was no surprise, then, that as soon as news trickled in of the attack on the Congress convoy in Bastar, the party’s vice-president, Rahul Gandhi, should have taken off for Raipur. It was a commendable journey of political solidarity. It would be interesting to find out if the bloody massacre in Sukma has helped Mr. Gandhi re-set his ideological compass.

Let it be recalled that this is the same Mr. Gandhi who had allowed himself to be persuaded in August 2010 to travel to the Niyamgiri Hills in Orissa, where he told the adivasis that he was their “sipahi,” or soldier in Delhi. Only two days before that visit, the Central government had pointedly withdrawn environmental permission to the Vedanta Group to mine the area for bauxite. For good measure, the young Gandhi had proclaimed that development meant that “every voice, including that of the poor and adivasis, should be heard.” It would be nice to know if Mr. Gandhi has resolved his ideological equivocations in the aftermath of the Chhattisgarh violence.

For two decades the Indian political class has gone about believing that “development” and “growth” are innocuous and painless. The prevailing orthodoxy insists that the Indian state has one and only one business: to get out of the businessman’s way. There is an unwillingness to acknowledge the basic nature of power: irrespective of its political arrangement, every society plays host to a ceaseless struggle over who gains what at whose expense. Growth and development invariably produce dislocation and dispossession. Good politics in a democratic idiom can go a long way in ameliorating the alienation and anger.

PRO-POOR INITIATIVES

The UPA’s approach has been to let the corporate marauders run amok while salving its democratic conscience with a slew of pro-poor, aam aadmi-centric initiatives. In the process, for the past nine years, the country has periodically been treated to a mock controversy over whether Sonia Gandhi’s National Advisory Council was usurping the government’s space and prerogatives, or, when this or that NAC member walks out in a huff, whether the government is not being sufficiently pro-poor. The UPA’s approach neither mollifies the corporate buccaneers nor satisfies the poor and the disadvantaged.

The corporates, however, have sized up the divided political leadership across the spectrum. They have finessed their tactics. If a government is slow to give them the policy breaks that they demand, the democratic space and its anarchic habits will be creatively used to unleash civil unrest on this or that pretext. There is always the age old anger against “corruption” to be tapped. And, as it were, one can always rely on an auditor or a judge to step in to divert attention away from corporate misdemeanours of the most serious kind.

PINCER MOVEMENT

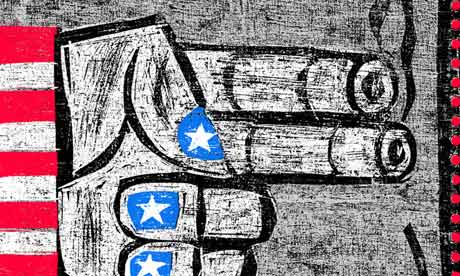

No wonder, then, that the Indian state is caught in a pincer movement. From one side, the ideologues and practitioners of “growth” are unrelenting in their insistence that the country’s natural resources and citizens’ savings be made available to them for exploitation; and, from the other direction, the state is confronted by a vast underclass that is unwilling to see any reason to sacrifice its land and forests so that some others can enjoy the benefit of “progress.” Just as the corporates have served sufficient notice that they have no qualms in taking the state on and causing misery to its political functionaries, the underclass, too, is willing to match the state’s capacity for violence, bullet for bullet.

Both the Murthys and the Maoists are forcing the Indian state to take a stand. For too long, the Indian political leadership has refused to confront the Grand Conundrum: for whom does the state exist, whom does the state seek to reward and whom does it strive to protect against whom. The UPA leadership has neither the appetite for a brutal repression of the angry tribal, nor is it likely to be able to lure the Naxalites into a democratic engagement without a demonstrable capacity to stand up to corporate greed. A kind of alternative arrangement is already on the drawing board: the Gujarat model of no dissent, no trade unions, no civil society, no Medha Patkar, no tribal resistance, no protests.

The great sociologist, Edward Shils, once observed that every society needs grandiose visions and austere standards; the political and intellectual leadership is obliged to prod society to its own historical ideals — “elements which must be recurrently realized without even being definitively realizable, once and for all.” Perhaps we should be thankful that both the Murthys and the Maoists are inviting us to find a vision for India that is morally defensible.