It has to be but a means to development, not an end in itself

Is

India doing marvellously well, or is it failing terribly? Depending on

whom you speak to, you could pick up either of those answers with some

frequency. One story, very popular among a minority but a large enough

group—of Indians who are doing very well (and among the media that cater

largely to them)—runs something like this. “After decades of mediocrity

and stagnation under ‘Nehruvian socialism’, the Indian economy achieved

a spectacular take-off during the last two decades. This take-off,

which led to unprecedented improvements in income per head, was driven

largely by market initiatives. It involves a significant increase in

inequality, but this is a common phenomenon in periods of rapid growth.

With enough time, the benefits of fast economic growth will surely reach

even the poorest people, and we are firmly on the way to that.” Despite

the conceptual confusion involved in bestowing the term ‘socialism’ to a

collectivity of grossly statist policies of ‘Licence raj’ and neglect

of the state’s responsibilities for school education and healthcare, the

story just told has much plausibility, within its confined domain.

But looking at contemporary India from another angle, one could equally tell the following—more critical and more censorious—story: “The progress of living standards for common people, as opposed to a favoured minority, has been dreadfully slow—so slow that India’s social indicators are still abysmal.” For instance, according to World Bank data, only five countries outside Africa (Afghanistan, Bhutan, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea and Yemen) have a lower “youth female literacy rate” than India (World Development Indicators 2011, online). To take some other examples, only four countries (Afghanistan, Cambodia, Haiti, Myanmar and Pakistan) do worse than India in child mortality rate; only three have lower levels of “access to improved sanitation” (Bolivia, Cambodia and Haiti); and none (anywhere—not even in Africa) have a higher proportion of underweight children. Almost any composite index of these and related indicators of health, education and nutrition would place India very close to the bottom in a ranking of all countries outside Africa.

Growth and Development

So which of the two stories—unprecedented success or extraordinary failure—is correct? The answer is both, for they are both valid, and they are entirely compatible with each other. This may initially seem like a bit of a mystery, but that initial thought would only reflect a failure to understand the demands of development that go well beyond economic growth. Indeed, economic growth is not constitutively the same thing as development, in the sense of a general improvement in living standards and enhancement of people’s well-being and freedom. Growth, of course, can be very helpful in achieving development, but this requires active public policies to ensure that the fruits of economic growth are widely shared, and also requires—and this is very important—making good use of the public revenue generated by fast economic growth for social services, especially for public healthcare and public education.

But looking at contemporary India from another angle, one could equally tell the following—more critical and more censorious—story: “The progress of living standards for common people, as opposed to a favoured minority, has been dreadfully slow—so slow that India’s social indicators are still abysmal.” For instance, according to World Bank data, only five countries outside Africa (Afghanistan, Bhutan, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea and Yemen) have a lower “youth female literacy rate” than India (World Development Indicators 2011, online). To take some other examples, only four countries (Afghanistan, Cambodia, Haiti, Myanmar and Pakistan) do worse than India in child mortality rate; only three have lower levels of “access to improved sanitation” (Bolivia, Cambodia and Haiti); and none (anywhere—not even in Africa) have a higher proportion of underweight children. Almost any composite index of these and related indicators of health, education and nutrition would place India very close to the bottom in a ranking of all countries outside Africa.

Growth and Development

So which of the two stories—unprecedented success or extraordinary failure—is correct? The answer is both, for they are both valid, and they are entirely compatible with each other. This may initially seem like a bit of a mystery, but that initial thought would only reflect a failure to understand the demands of development that go well beyond economic growth. Indeed, economic growth is not constitutively the same thing as development, in the sense of a general improvement in living standards and enhancement of people’s well-being and freedom. Growth, of course, can be very helpful in achieving development, but this requires active public policies to ensure that the fruits of economic growth are widely shared, and also requires—and this is very important—making good use of the public revenue generated by fast economic growth for social services, especially for public healthcare and public education.

|

We referred to this process as “growth-mediated” development in our 1989 book, Hunger and Public Action.

This can indeed be an effective route to a very important part of

development; but we must be clear about what can be achieved by fast

economic growth on its own, and what it cannot do without appropriate

social supplementation. Sustainable economic growth can be a huge force

not only for raising incomes but also for enhancing people’s living

standards and the quality of life, and it can also work very effectively

for many other objectives, such as reducing public deficits and the

burden of public debt. These growth connections do deserve emphasis, not

only in Asia, Africa and Latin America, but also very much in Europe

today, where there has been a remarkable lack of understanding of the

role of growth in solving problems of debt and deficit. There is a

tendency to concentrate only on draconian restrictive policies to cut

down public expenditure, no matter how essential and no matter how these

policies kill the goose that lays the golden egg of economic growth.

There is a neglect of the role of economic growth in economic and

financial stability in the European debate, with its focus only on

cutting public expenditure to satisfy the market and to obey the orders

of credit rating agencies.

Yet it is also important to recognise that the impact of economic growth on living standards is crucially dependent on the nature of the growth process (for instance, its sectoral composition and employment intensity) as well as of the public policies—particularly relating to basic education and healthcare—that are used to enable common people to share in the process of growth. There is also, in India, an urgent need for greater attention to the destructive aspects of growth, including environmental plunder (e.g. through razing of forests, indiscriminate mining, depletion of groundwater, drying of rivers and massacre of fauna) and involuntary displacement of communities—particularly adivasi communities—that have strong roots in a particular ecosystem.

Yet it is also important to recognise that the impact of economic growth on living standards is crucially dependent on the nature of the growth process (for instance, its sectoral composition and employment intensity) as well as of the public policies—particularly relating to basic education and healthcare—that are used to enable common people to share in the process of growth. There is also, in India, an urgent need for greater attention to the destructive aspects of growth, including environmental plunder (e.g. through razing of forests, indiscriminate mining, depletion of groundwater, drying of rivers and massacre of fauna) and involuntary displacement of communities—particularly adivasi communities—that have strong roots in a particular ecosystem.

|

India’s

growth achievements are indeed quite remarkable. According to official

data, per capita income has grown at a compound rate of close to five

per cent per year in real terms between 1990-91 and 2009-10. The more

recent rates of expansion are faster still: according to Planning

Commission estimates, the growth rate of GDP was 7.8 per cent in the

Tenth Plan period (2002-03 to 2006-07) and is likely to be around 8 per

cent in the Eleventh Plan period (2007-08 to 2011-12). The “advance

estimate” for 2010-11 is 8.6 per cent. These are, no doubt, exceptional

growth rates—the second-highest in the world, next to China. These

dazzling figures are, understandably, causing some excitement, and were

even described as “magic numbers” by no less than Lord Meghnad Desai,

who argued, not without irony, that whatever else happens, “the

government can still sit back and say 8.6 per cent”.

India does need rapid economic growth, if only because average incomes are so low that they cannot sustain anything like reasonable living standards, even with extensive income redistribution. Indeed, even today, after 20 years of rapid growth, India is still one of the poorest countries in the world, something that is often lost sight of, especially by those who enjoy world-class living standards thanks to the inequalities in the income distribution. According to World Development Indicators 2011, only 16 countries outside Africa had a lower “gross national income per capita” than India in 2010: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Haiti, Iraq, Kyrgyzstan, Lao, Moldova, Nepal, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Vietnam and Yemen. This is not exactly a club of economic superpowers.

|

Having

said this, it would be a mistake to “sit back” and rely on economic

growth per se to transform the living conditions of the unprivileged.

Along with our discussion of “growth-mediated” development, in an

earlier book, we also drew attention to the pitfalls of “unaimed

opulence”—the indiscriminate pursuit of economic expansion, without

paying much attention to how it is shared or how it affects people’s

lives. A good example, at that time (in the late 1980s), was Brazil,

where rapid growth went hand in hand with the persistence of massive

deprivation. Contrasting this with a more equitable growth pattern in

South Korea, we wrote “India stands in some danger of going Brazil’s

way, rather than South Korea’s”. Recent experience vindicates this

apprehension. Interestingly, in the meantime, Brazil has substantially

changed course, and adopted far more active social policies, including a

constitutional guarantee of free and universal healthcare as well as

bold programmes of social security and economic redistribution (such as

Bolsa Familia). This is one reason why Brazil is now doing quite well,

with, for instance, an infant mortality rate of only 9 per 1,000

(compared with 48 in India), 99 per cent literacy among women aged 15-24

years (74 per cent in India), and only 2.2 per cent of children below

five being underweight (compared with a staggering 44 per cent in

India). While India has much to learn from earlier experiences of

growth-mediated development elsewhere in the world, it must avoid

unaimed opulence—an undependable, wasteful way of improving the living

standards of the poor.

India’s Decline in South Asia

One indication that something is not quite right with India’s development strategy is the fact that India has started falling behind every other South Asian country (with the partial exception of Pakistan) in terms of social indicators, even as it is doing so well in terms of per capita income (see table below).

The comparison between Bangladesh and India is a good place to start. During the last 20 years or so, India has grown much richer than Bangladesh: per capita income was estimated to be 60 per cent higher in India than in Bangladesh in 1990, and 98 per cent higher (about double) in 2010. But during the same period, Bangladesh has overtaken India in terms of a wide range of basic social indicators: life expectancy, child survival, fertility rates, immunisation rates, and even some (not all) schooling indicators such as estimated “mean years of schooling”. For instance, life expectancy was estimated to be four years longer in India than in Bangladesh in 1990, but it had become three years shorter by 2008. Similarly, the child mortality rate was estimated to be about 24 per cent higher in Bangladesh than in India in 1990, but it was 24 per cent lower in Bangladesh in 2009. Most social indicators now look better in Bangladesh than in India, despite Bangladesh having barely half of India’s per capita income.

No less intriguing is that Nepal also seems to be catching up rapidly with India, and even overtaking India in some respects. Around 1990, Nepal was way behind India in terms of almost every development indicator. Today, social indicators for both countries are much the same (sometimes a little better in India still, sometimes the reverse), in spite of per capita income in India being about three times as high as in Nepal.

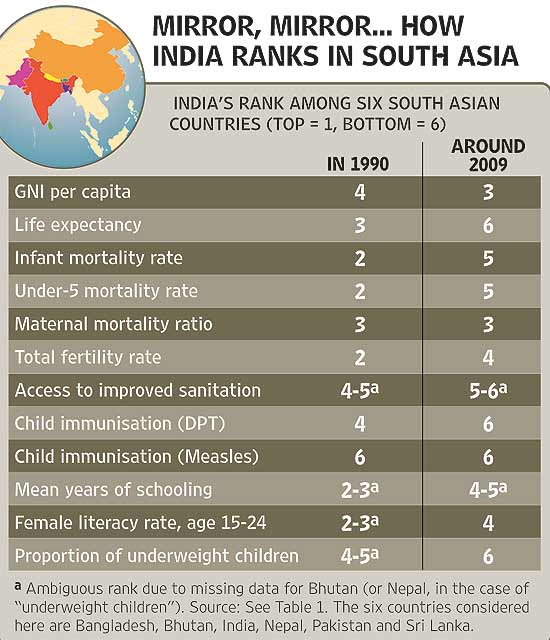

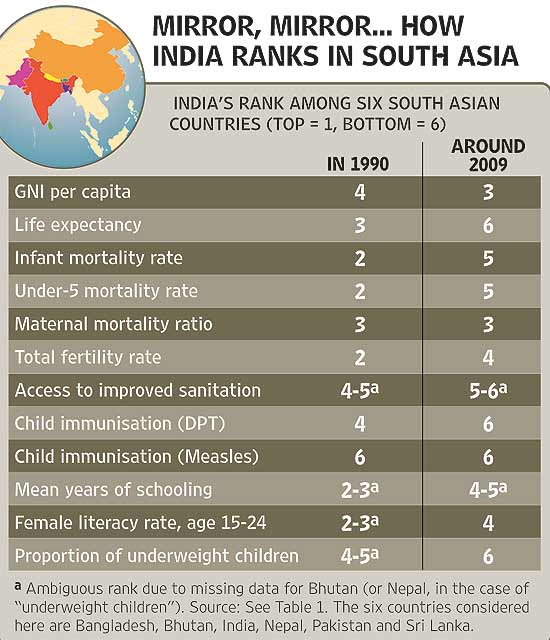

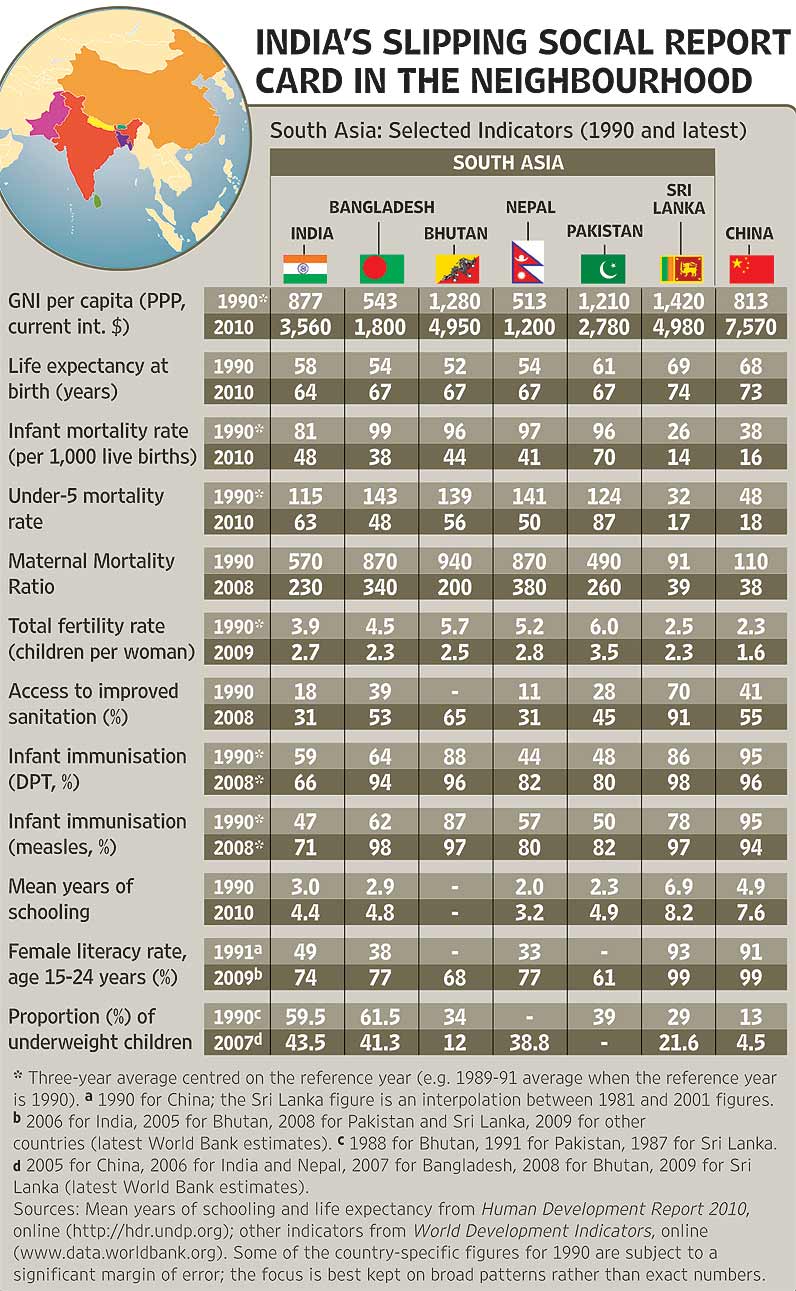

To look at the same issue from another angle, Table 2 displays India’s “rank” among South Asia’s six major countries (excluding tiny Maldives), around 1990 as well as today (more precisely, in the latest year for which comparable international data are available). As expected, in terms of per capita income, India’s rank has improved—from fourth (after Bhutan, Pakistan and Sri Lanka) to third (after Bhutan and Sri Lanka). But in most other respects, India’s rank has worsened, in fact, quite sharply in many cases. Overall, India had the best social indicators in South Asia in 1990, next to Sri Lanka, but now looks second-worst, ahead of only Pakistan. Looking at their South Asian neighbours, the Indian poor are entitled to wonder what they have gained—at least so far—from the acceleration of economic growth.

India and China

One of the requirements of successful growth-mediated development is the skilful use of the opportunities provided by increasing public revenue. There are interesting and important contrasts in the policies followed by different countries in this respect. Since China is often cited by advocates of a single-minded focus on economic growth, it is interesting to compare what China does with what India has been doing. China makes much better use of the opportunities offered by high economic growth to expand public resources for development purposes. For example, government expenditure on healthcare in China is nearly four times that in India (after adjusting for “purchasing power parity”—the gap is even larger otherwise). China does, of course, have a larger population and a higher per capita income than India, but even as a ratio of GDP, public expenditure on health is much higher in China (about 2.3 per cent) than in India (around 1.4 per cent).

As

Table 1 illustrates, China has much higher values of most social

indicators of living standards, such as life expectancy (73 years in

China and 64 years in India), infant mortality rate (16 per thousand in

China and 48 in India), mean years of schooling (estimated to be 7.6

years in China, compared with only 4.4 years in India), or the coverage

of immunisation (very close to universal in China but only around

two-thirds in India, for DPT and measles). While India has nearly caught

up with China in terms of the rate of economic growth, it seems quite

far behind China in terms of the use of public resources for social

support, and correspondingly, it has not done nearly as well in

translating growth into rapid progress of social indicators. While there

are also, undoubtedly, other factors behind the China-India contrast,

the differing use of the fruits of growth for social support would seem

to be an important influence in this contrasting picture.

It is not at all our purpose to argue that India should learn from China in every respect. India has reasons to value its democratic institutions. Even with all their limitations, these institutions allow for a wide variety of voices to be heard, and facilitate significant opportunities for various forms of public participation in governance. There are, of course, many failings of Indian democracy (which we have discussed in our writings), but there are big democratic achievements as well, and also the hindrances can be addressed through democratic battles to remove them. If China officially executes more people in a week than India has done since Independence (and this is true of a shockingly large number of weeks every year in China), this comparison, like many others involving legal and human rights of citizens, is not to India’s disadvantage. If there is something to learn from China, especially about how to ensure that the fruits of economic growth are more widely shared, then that is a case for learning from what there is to learn, not a case for blind imitation.

India’s Decline in South Asia

One indication that something is not quite right with India’s development strategy is the fact that India has started falling behind every other South Asian country (with the partial exception of Pakistan) in terms of social indicators, even as it is doing so well in terms of per capita income (see table below).

|

The comparison between Bangladesh and India is a good place to start. During the last 20 years or so, India has grown much richer than Bangladesh: per capita income was estimated to be 60 per cent higher in India than in Bangladesh in 1990, and 98 per cent higher (about double) in 2010. But during the same period, Bangladesh has overtaken India in terms of a wide range of basic social indicators: life expectancy, child survival, fertility rates, immunisation rates, and even some (not all) schooling indicators such as estimated “mean years of schooling”. For instance, life expectancy was estimated to be four years longer in India than in Bangladesh in 1990, but it had become three years shorter by 2008. Similarly, the child mortality rate was estimated to be about 24 per cent higher in Bangladesh than in India in 1990, but it was 24 per cent lower in Bangladesh in 2009. Most social indicators now look better in Bangladesh than in India, despite Bangladesh having barely half of India’s per capita income.

No less intriguing is that Nepal also seems to be catching up rapidly with India, and even overtaking India in some respects. Around 1990, Nepal was way behind India in terms of almost every development indicator. Today, social indicators for both countries are much the same (sometimes a little better in India still, sometimes the reverse), in spite of per capita income in India being about three times as high as in Nepal.

To look at the same issue from another angle, Table 2 displays India’s “rank” among South Asia’s six major countries (excluding tiny Maldives), around 1990 as well as today (more precisely, in the latest year for which comparable international data are available). As expected, in terms of per capita income, India’s rank has improved—from fourth (after Bhutan, Pakistan and Sri Lanka) to third (after Bhutan and Sri Lanka). But in most other respects, India’s rank has worsened, in fact, quite sharply in many cases. Overall, India had the best social indicators in South Asia in 1990, next to Sri Lanka, but now looks second-worst, ahead of only Pakistan. Looking at their South Asian neighbours, the Indian poor are entitled to wonder what they have gained—at least so far—from the acceleration of economic growth.

India and China

One of the requirements of successful growth-mediated development is the skilful use of the opportunities provided by increasing public revenue. There are interesting and important contrasts in the policies followed by different countries in this respect. Since China is often cited by advocates of a single-minded focus on economic growth, it is interesting to compare what China does with what India has been doing. China makes much better use of the opportunities offered by high economic growth to expand public resources for development purposes. For example, government expenditure on healthcare in China is nearly four times that in India (after adjusting for “purchasing power parity”—the gap is even larger otherwise). China does, of course, have a larger population and a higher per capita income than India, but even as a ratio of GDP, public expenditure on health is much higher in China (about 2.3 per cent) than in India (around 1.4 per cent).

|

It is not at all our purpose to argue that India should learn from China in every respect. India has reasons to value its democratic institutions. Even with all their limitations, these institutions allow for a wide variety of voices to be heard, and facilitate significant opportunities for various forms of public participation in governance. There are, of course, many failings of Indian democracy (which we have discussed in our writings), but there are big democratic achievements as well, and also the hindrances can be addressed through democratic battles to remove them. If China officially executes more people in a week than India has done since Independence (and this is true of a shockingly large number of weeks every year in China), this comparison, like many others involving legal and human rights of citizens, is not to India’s disadvantage. If there is something to learn from China, especially about how to ensure that the fruits of economic growth are more widely shared, then that is a case for learning from what there is to learn, not a case for blind imitation.

|

The

China-India contrast does, however, raise another interesting question:

could it be that India’s democratic system is a barrier to using the

fruits of economic growth for the purpose of enhancing health, education

and other aspects of “social development”? In addressing this question,

there is some possibility of a sense of nostalgia. When India had a

very low rate of economic growth, a common argument coming from the

critics of democracy was that democracy was hostile to fast economic

growth. It was hard, at that time, to convince the anti-democratic

advocates that fast economic growth depends on the friendliness of the

economic climate, rather than on the fierceness of political systems.

That debate on the alleged contradiction between democracy and economic

growth has now ended (not least because of the high economic growth

rates of democratic India), but a similar scepticism about democracy

seems to be now emerging, suggesting an alleged inability of democratic

systems to pursue public health, public education and other socially

supportive arrangements.

It is important in this context to understand how democratic decisions emerge and how policies get adopted. What a democratic system achieves depends greatly on the issues that are politicised, which contributes to their advancement. Some issues are extremely easy to politicise, such as the calamity of a famine—and as a result famines tend to stop abruptly with the establishment of a democratic political system. But other issues—less spectacular and less immediate—present a much harder challenge. Using democratic means for remedying inadequate coverage of public healthcare, non-extreme undernourishment, or inadequate opportunities for school education demands more from democratic practice—more vigour and much more range.

Authoritarian

systems can change their policies very quickly, when the leaders want

that, and it is to the credit of the Chinese political leaders that they

have focused so much on social interventions in education, healthcare

and other supportive mechanisms to advance the quality of life of the

Chinese people. But authoritarianism does not, of course, provide any

kind of guarantee that the social commitments will emerge (they clearly

have not in North Korea or Burma), or that they would invariably be

stable and non-fragile (there have been sharp variations in the past

even in China, including its having the largest famine in world history

during the failure of the Great Leap Forward initiative).

Even China’s commitment to broad-based public healthcare has had ups

and downs, and came close to being undone: the coverage of the rural

cooperative medical system crashed from 90 per cent to 10 per cent

between 1976 and 1983 (when market-oriented reforms were initiated), and

stayed around 10 per cent for a full 20 years. During this period of

abdication of state responsibility for healthcare in China, the progress

of health-related indicators (such as life expectancy and child

survival) slowed down sharply. This led eventually to another U-turn,

around 2004-5, when the rural cooperative medical system was rebuilt,

with the coverage rising again to 90 per cent or so within three years

(Shaoguang Wang, ‘Double Movement in China’, Economic and Political Weekly, Dec 27, 2008).

Power Imbalances, Old and New

The neglect of elementary education, healthcare, social security and related matters in Indian planning fits into a general pattern of pervasive imbalance of political and economic power that leads to a massive neglect of the interests of the unprivileged. Other glaring manifestations of this pattern include disregard for agriculture and rural development, environmental plunder for private gain with huge social losses, large-scale displacement of rural communities without adequate compensation, and the odd tolerance of human rights violations when the victims come from the underdogs of society.

None

of this is entirely new, and much of it reflects good old inequalities

of class, caste and gender that have been around for a long time. For

instance, the fact that not even one of the 315 editors and other

leading members of the printed and electronic media in Delhi surveyed

recently by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies belonged to

a scheduled caste or scheduled tribe, and that at the other end, 90 per

cent belonged to a small coterie of upper castes that make up only 16

per cent of the population, obviously does not help to ensure that the

concerns of Dalits and adivasis are adequately represented in public

debates. Nor is India’s male-dominated Lok Sabha (where the proportion

of women has never crossed 10 per cent so far) well placed to address

the concerns of women—not only gender issues, but also other social

issues in which women may have a strong stake. A similar point applies

to rural-urban disparities: a recent study found that rural issues get

only two per cent of the total news coverage in national dailies.

Some of these inequalities are diminishing, making it easier for disadvantaged groups to gain a voice in the system (even the proportion of women in the Lok Sabha, abysmally low as it is, is about three times as high today as it was 50 years ago). However, new or rising inequalities are also reinforcing the vicious circle of disempowerment and deprivation. For instance, the last 20 years have seen a massive growth of corporate power in India, a force that is largely driven—with some honourable exceptions—by unrestrained search for profits. The growing influence of corporate interests on public policy and democratic institutions does not particularly facilitate the reorientation of policy priorities towards the needs of the unprivileged.

It is important in this context to understand how democratic decisions emerge and how policies get adopted. What a democratic system achieves depends greatly on the issues that are politicised, which contributes to their advancement. Some issues are extremely easy to politicise, such as the calamity of a famine—and as a result famines tend to stop abruptly with the establishment of a democratic political system. But other issues—less spectacular and less immediate—present a much harder challenge. Using democratic means for remedying inadequate coverage of public healthcare, non-extreme undernourishment, or inadequate opportunities for school education demands more from democratic practice—more vigour and much more range.

|

You call this education? A government school in Lucknow. (Photograph by Nirala Tripathi)

There is, in fact, no real barrier in India in combining multi-party

democratic governance with active social intervention. But what would be

needed is much greater public engagement with the central demands of

justice and development through more vigorous democratic practice. The

development of the welfare state in Europe has many lessons to offer

here. As it happens, public debate is quite powerful in India, but the

range of engagement has often been quite limited. The India-China

comparisons tend to concentrate mostly on the horse race of relative

rates of overall economic growth rather than the variations in mediation

for development. Underlying this dialogic narrowness, there is a social

picture. A big part of the Indian population—a fairly small minority

but still quite large in absolute numbers—has been doing very well

indeed, through the process of high growth alone; they do not depend on

social mediation. In contrast, more vigorous mediation would be very

important for other Indians—many more, in fact—whose lives are affected

by ill health, undernourishment, lack of healthcare and other

deprivations.Power Imbalances, Old and New

The neglect of elementary education, healthcare, social security and related matters in Indian planning fits into a general pattern of pervasive imbalance of political and economic power that leads to a massive neglect of the interests of the unprivileged. Other glaring manifestations of this pattern include disregard for agriculture and rural development, environmental plunder for private gain with huge social losses, large-scale displacement of rural communities without adequate compensation, and the odd tolerance of human rights violations when the victims come from the underdogs of society.

|

Some of these inequalities are diminishing, making it easier for disadvantaged groups to gain a voice in the system (even the proportion of women in the Lok Sabha, abysmally low as it is, is about three times as high today as it was 50 years ago). However, new or rising inequalities are also reinforcing the vicious circle of disempowerment and deprivation. For instance, the last 20 years have seen a massive growth of corporate power in India, a force that is largely driven—with some honourable exceptions—by unrestrained search for profits. The growing influence of corporate interests on public policy and democratic institutions does not particularly facilitate the reorientation of policy priorities towards the needs of the unprivileged.

|

It

is important to recognise the influence of elements of the corporate

sector on the balance of public policies, but it would be wrong to take

that to be something like an irresistible natural force. India’s

democratic system offers ways and means of resisting the new biases that

may emanate from the pressure of business firms. One instructive

example both of a naked attempt to denude an established public service

and of the possibility of defeating such an attempt is the long saga of

attempted takeover of India’s school meal programme by biscuit-making

firms. The “midday meal” programme, which provides hot cooked meals

prepared by local women to some 120 million children, with a substantial

impact on both nutrition and school attendance, had been eyed for many

years by food manufacturers, especially the biscuits industry.

A few years ago, a “Biscuit Manufacturers’ Association” (BMA) launched a massive campaign for the replacement of cooked school meals with branded biscuit packets. The BMA wrote to all members of Parliament, asking them to plead the case for biscuits with the minister concerned and assisting them in this task with a neat pseudo-scientific precis of the wonders of manufactured biscuits. Dozens of MPs, across most of the political parties, promptly obliged by writing to the minister and rehashing the BMA’s bogus claims. According to one senior official, the ministry was “flooded” with such letters, 29 of which were obtained later under the Right to Information Act. Fortunately, the proposal was firmly shot down by the ministry after being referred to state governments and nutrition experts, and public vigilance exposed what was going on. The minister, in fact, wrote to a chief minister who sympathised with the biscuit lobby: “We are, indeed, dismayed at the growing requests for introduction of pre-cooked foods, emanating largely from suppliers/marketers of packaged foods, and aimed essentially at penetrating and deepening the market for such foods” (Hindustan Times, Apr 14, 2008).

The bigger battle is still on. The BMA itself did not give up after being rebuked by the Union minister for human resource development. It proceeded to write to the Union minister for women and child development, with a similar proposal for supplying biscuits to children below the age of six years under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS). Other food manufacturers are also on the job, and despite much vigilance and resistance from activist quarters (and the Supreme Court), they seem to have made significant inroads into child feeding programmes in several states.

Similar concerns apply in other fields of social policy. For instance, the prospects of building a public healthcare system in India are unlikely to be helped by the growing influence of commercial insurance companies, very active in the field of health. India’s health system is already one of the most privatised in the world, with predictable consequences—high expenditure, low achievements and massive inequalities. Yet, there is much pressure to embrace this “American model” of healthcare provision, despite the international recognition in the health community of its comparatively low achievement and significantly high cost.

Rosy picture Himachal leads the way in social indices. (Photograph by Tribhuvan Tiwari)

However, recent events have also shown the possibility of fighting back, not just in terms of winning isolated battles against inappropriate corporate influence, as happened with the biscuits lobby, but also in terms of building institutional safeguards against abuses of corporate power. The Right to Information Act, for instance, though not directly applicable to information held by private corporations, is a powerful means of watching and containing the state-corporate nexus, as the biscuits story illustrates. Regulations and legislations pertaining to corporate funding of political parties, corporate social responsibility, financial transparency, environmental standards, and workers’ rights also have an important role to play in disciplining the corporate sector.

The Case for a Comprehensive Approach

The need for growth-mediated development has not been completely ignored in Indian policy debates. The official goal of “inclusive growth” could even claim to have much the same connotation. However, the rhetoric of inclusive growth has gone hand in hand with elitist policies that often end up promoting a two-track society whereby superior (“world-class”) facilities are being created for the privileged, while the unprivileged receive second-rate treatment, or are left to their own devices, or even become the target of active repression—as happens, for instance, in cases of forcible displacement without compensation, with a little help from the police. Social policies, for their part, remain quite restrictive (despite some significant, hard-won initiatives such as the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act), and are increasingly steered towards quick fixes such as conditional cash transfers. Their coverage, in many cases, is also sought to be confined to “below poverty line” (BPL) families, a narrowly defined category that tends to shrink over time as per capita incomes increase, which may even look like a convenient way of ensuring that social welfare programmes are “self-liquidating”.

A few years ago, a “Biscuit Manufacturers’ Association” (BMA) launched a massive campaign for the replacement of cooked school meals with branded biscuit packets. The BMA wrote to all members of Parliament, asking them to plead the case for biscuits with the minister concerned and assisting them in this task with a neat pseudo-scientific precis of the wonders of manufactured biscuits. Dozens of MPs, across most of the political parties, promptly obliged by writing to the minister and rehashing the BMA’s bogus claims. According to one senior official, the ministry was “flooded” with such letters, 29 of which were obtained later under the Right to Information Act. Fortunately, the proposal was firmly shot down by the ministry after being referred to state governments and nutrition experts, and public vigilance exposed what was going on. The minister, in fact, wrote to a chief minister who sympathised with the biscuit lobby: “We are, indeed, dismayed at the growing requests for introduction of pre-cooked foods, emanating largely from suppliers/marketers of packaged foods, and aimed essentially at penetrating and deepening the market for such foods” (Hindustan Times, Apr 14, 2008).

The bigger battle is still on. The BMA itself did not give up after being rebuked by the Union minister for human resource development. It proceeded to write to the Union minister for women and child development, with a similar proposal for supplying biscuits to children below the age of six years under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS). Other food manufacturers are also on the job, and despite much vigilance and resistance from activist quarters (and the Supreme Court), they seem to have made significant inroads into child feeding programmes in several states.

Similar concerns apply in other fields of social policy. For instance, the prospects of building a public healthcare system in India are unlikely to be helped by the growing influence of commercial insurance companies, very active in the field of health. India’s health system is already one of the most privatised in the world, with predictable consequences—high expenditure, low achievements and massive inequalities. Yet, there is much pressure to embrace this “American model” of healthcare provision, despite the international recognition in the health community of its comparatively low achievement and significantly high cost.

Rosy picture Himachal leads the way in social indices. (Photograph by Tribhuvan Tiwari)

However, recent events have also shown the possibility of fighting back, not just in terms of winning isolated battles against inappropriate corporate influence, as happened with the biscuits lobby, but also in terms of building institutional safeguards against abuses of corporate power. The Right to Information Act, for instance, though not directly applicable to information held by private corporations, is a powerful means of watching and containing the state-corporate nexus, as the biscuits story illustrates. Regulations and legislations pertaining to corporate funding of political parties, corporate social responsibility, financial transparency, environmental standards, and workers’ rights also have an important role to play in disciplining the corporate sector.

The Case for a Comprehensive Approach

The need for growth-mediated development has not been completely ignored in Indian policy debates. The official goal of “inclusive growth” could even claim to have much the same connotation. However, the rhetoric of inclusive growth has gone hand in hand with elitist policies that often end up promoting a two-track society whereby superior (“world-class”) facilities are being created for the privileged, while the unprivileged receive second-rate treatment, or are left to their own devices, or even become the target of active repression—as happens, for instance, in cases of forcible displacement without compensation, with a little help from the police. Social policies, for their part, remain quite restrictive (despite some significant, hard-won initiatives such as the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act), and are increasingly steered towards quick fixes such as conditional cash transfers. Their coverage, in many cases, is also sought to be confined to “below poverty line” (BPL) families, a narrowly defined category that tends to shrink over time as per capita incomes increase, which may even look like a convenient way of ensuring that social welfare programmes are “self-liquidating”.

|

Cash

transfers are increasingly seen as a potential cornerstone of social

policy in India, often based on a distorted reading of the Latin

American experience in this respect. There are, of course, strong

arguments for cash transfers (conditional or unconditional) in some

circumstances, just as there are good arguments for transfers in kind

(such as midday meals for school children). What is remarkably

dangerous, however, is the illusion that cash transfers (more precisely,

“conditional cash transfers”) can replace public services by inducing

recipients to buy health and education services from private providers.

This is not only hard to substantiate on the basis of realistic

empirical reading; it is, in fact, entirely contrary to the historical

experience of Europe, America, Japan and East Asia in their respective

transformation of living standards. Also, it is not how conditional cash

transfers work in Brazil or Mexico or other successful cases today.

In Latin America, conditional cash transfers usually act as a complement, not a substitute, for public provision of health, education and other basic services. The incentives work for their supplementing purpose because the basic public services are there in the first place. In Brazil, for instance, basic health services such as immunisation, antenatal care and skilled attendance at birth are virtually universal. The state has done its homework—almost half of all health expenditure in Brazil is public expenditure, compared with barely one quarter (of a much lower total of health expenditure) in India. In this situation, providing incentives to complete the universalisation of healthcare may be quite sensible. In India, however, these basic services are still largely missing, and conditional cash transfers cannot fill the gap.

Poor initiatives Jairam and Montek discussing the poverty line at a press conference. (Photograph by Jitender Gupta)

The pitfalls of “BPL targeting” have become increasingly clear in recent years. First, there is no reliable way of identifying poor households, and the exclusion errors are enormous: at least three national surveys indicate that, around 2004-05, about half of all poor households in rural India did not have a “BPL card”. Second, India’s poverty line is abysmally low, so that even if all the BPL cards were correctly and infallibly allocated to poor households, large numbers of people who are in dire need of social support would remain excluded from the system. In 2009-10, for instance, the official poverty line in Delhi was around Rs 30 per person per day. This is just about enough to buy one kilogram of rice and a one-way bus ticket that would take you three stops down the road. Third, BPL targeting is extremely divisive, and undermines the unity and strength of public demand for functional social services, making a collaborative right into a divisive privilege.

The power of comprehensiveness in social policy is evident not only from international and historical experience, but also from contemporary experience in India itself. In at least three Indian states, universal provision of essential services has become an accepted norm. Kerala has a long history of comprehensive social policies, particularly in the field of elementary education—the principle of universal education at public expense was an explicit objective of state policy in Travancore as early as 1817. Early universalisation of elementary education is the cornerstone of Kerala’s wide-ranging social achievements.

Less well known, but no less significant, is the gradual emergence and consolidation of universalistic social policies in Tamil Nadu (see ‘Understanding Public Services in Tamil Nadu’ by Vivek S., PhD thesis, 2010, Syracuse University, and the literature cited there). Tamil Nadu was the first state to introduce free and universal midday meals in primary schools. This initiative, much derided at that time as a “populist” programme, later became a model for India’s national midday meal programme, widely regarded today as one of the best “centrally sponsored schemes”. The state’s pioneering efforts in the field of early child care, under the ICDS, has made great strides towards the provision of functional anganwadis (child care centres), accessible to all, in every habitation. Tamil Nadu, unlike most other states, also has an extensive network of lively and effective healthcare centres, where people from all social backgrounds can get reasonably good healthcare, free of cost. NREGA, another example of universalistic social programme, is also doing well in Tamil Nadu: employment levels are high (with about 80 per cent of the work going to women), wages are usually paid on time and leakages are relatively small. Last but not the least, Tamil Nadu has a universal public distribution system (PDS), in both rural and urban areas. Tamil Nadu’s pds supplies not only foodgrains but also oil, pulses and other food commodities, with astonishing regularity and minimal leakages.

Protests against Vedanta in Orissa

Himachal Pradesh began this journey much later than Kerala and Tamil Nadu, but is catching up very quickly. This is most evident in the field of elementary education: starting from literacy levels similar to the dismal figures for Bihar or Uttar Pradesh around the time of India’s Independence, Himachal Pradesh caught up with the highest-performing Kerala within a few decades. This “schooling revolution” was based almost entirely on a policy of universal provision of government schools, and even today, elementary education in Himachal Pradesh is overwhelmingly in the public sector. Like Tamil Nadu, Himachal Pradesh has a well-functioning pds, providing not only foodgrain but also pulses and oil and covering both “BPL” (Below Poverty Line) and “APL” (Above Poverty Line) families. Himachal Pradesh has also followed comprehensive principles not only in the provision of essential social services (including schooling facilities, healthcare and child care) but also in the provision of basic amenities such as roads, electricity, drinking water and public transport. For instance, in spite of adverse topography and scattered settlements, 98 per cent of Himachali households had electricity in 2005-6.

It is perhaps not an accident that Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Himachal Pradesh also tend to have the best social indicators among all major Indian states. For instance, a simple index of children’s health, education and nutrition achievements clearly places these three states at the top (Dreze, R. Khera, S. Narayanan, 2007, ‘Early Childhood in India: Facing the Facts’, Indian Journal of Human Development, 1(2), Jul-Dec 2007). Despite wide historical, cultural and political differences, they have converged towards a similar approach to social policy, and the results are much the same too. There is a crucial lesson here for other Indian states, and indeed for the country as a whole.

A Concluding Remark

We hope that the puzzle with which we began is a little clearer now. India’s recent development experience includes both spectacular success as well as massive failure. The growth record is very impressive, and provides an important basis for all-round development, not least by generating more public revenue (about four times as much today, in real terms, as in 1990). But there has also been a failure to ensure that rapid growth translates into better living conditions for the Indian people. It is not that they have not improved at all, but the pace of improvement has been very slow—even slower than in Bangladesh or Nepal. There is probably no other example in the history of world development of an economy growing so fast for so long with such limited results in terms of broad-based social progress.

There is no mystery in this contrast, or in the limited reach of India’s development efforts. Both reflect the nature of policy priorities in this period. But as we have argued, these priorities can change through democratic engagement—as has already happened to some extent in specific states. However, this requires a radical broadening of public discussion in India to development-related matters—rather than keeping it confined to simple comparisons of the growth of the gnp, and naive admiration (implicit or explicit) of the high living standards of a relatively small part of the population. An exaggerated concentration on the lives of the minority of the better-off, fed strongly by media interest, gives an unreal picture of the rosiness of what is happening to Indians in general, and stifles public dialogue of other issues. Imaginative democratic practice, we have argued, is essential for broadening and enhancing India’s development achievements.

Jean Dreze is Visiting Professor, Department of Economics, Allahabad University. Nobel laureate Amartya Sen is Lamont University professor and Professor of Economics and Philosophy at Harvard University.

In Latin America, conditional cash transfers usually act as a complement, not a substitute, for public provision of health, education and other basic services. The incentives work for their supplementing purpose because the basic public services are there in the first place. In Brazil, for instance, basic health services such as immunisation, antenatal care and skilled attendance at birth are virtually universal. The state has done its homework—almost half of all health expenditure in Brazil is public expenditure, compared with barely one quarter (of a much lower total of health expenditure) in India. In this situation, providing incentives to complete the universalisation of healthcare may be quite sensible. In India, however, these basic services are still largely missing, and conditional cash transfers cannot fill the gap.

Poor initiatives Jairam and Montek discussing the poverty line at a press conference. (Photograph by Jitender Gupta)

The pitfalls of “BPL targeting” have become increasingly clear in recent years. First, there is no reliable way of identifying poor households, and the exclusion errors are enormous: at least three national surveys indicate that, around 2004-05, about half of all poor households in rural India did not have a “BPL card”. Second, India’s poverty line is abysmally low, so that even if all the BPL cards were correctly and infallibly allocated to poor households, large numbers of people who are in dire need of social support would remain excluded from the system. In 2009-10, for instance, the official poverty line in Delhi was around Rs 30 per person per day. This is just about enough to buy one kilogram of rice and a one-way bus ticket that would take you three stops down the road. Third, BPL targeting is extremely divisive, and undermines the unity and strength of public demand for functional social services, making a collaborative right into a divisive privilege.

The power of comprehensiveness in social policy is evident not only from international and historical experience, but also from contemporary experience in India itself. In at least three Indian states, universal provision of essential services has become an accepted norm. Kerala has a long history of comprehensive social policies, particularly in the field of elementary education—the principle of universal education at public expense was an explicit objective of state policy in Travancore as early as 1817. Early universalisation of elementary education is the cornerstone of Kerala’s wide-ranging social achievements.

Less well known, but no less significant, is the gradual emergence and consolidation of universalistic social policies in Tamil Nadu (see ‘Understanding Public Services in Tamil Nadu’ by Vivek S., PhD thesis, 2010, Syracuse University, and the literature cited there). Tamil Nadu was the first state to introduce free and universal midday meals in primary schools. This initiative, much derided at that time as a “populist” programme, later became a model for India’s national midday meal programme, widely regarded today as one of the best “centrally sponsored schemes”. The state’s pioneering efforts in the field of early child care, under the ICDS, has made great strides towards the provision of functional anganwadis (child care centres), accessible to all, in every habitation. Tamil Nadu, unlike most other states, also has an extensive network of lively and effective healthcare centres, where people from all social backgrounds can get reasonably good healthcare, free of cost. NREGA, another example of universalistic social programme, is also doing well in Tamil Nadu: employment levels are high (with about 80 per cent of the work going to women), wages are usually paid on time and leakages are relatively small. Last but not the least, Tamil Nadu has a universal public distribution system (PDS), in both rural and urban areas. Tamil Nadu’s pds supplies not only foodgrains but also oil, pulses and other food commodities, with astonishing regularity and minimal leakages.

Protests against Vedanta in Orissa

Himachal Pradesh began this journey much later than Kerala and Tamil Nadu, but is catching up very quickly. This is most evident in the field of elementary education: starting from literacy levels similar to the dismal figures for Bihar or Uttar Pradesh around the time of India’s Independence, Himachal Pradesh caught up with the highest-performing Kerala within a few decades. This “schooling revolution” was based almost entirely on a policy of universal provision of government schools, and even today, elementary education in Himachal Pradesh is overwhelmingly in the public sector. Like Tamil Nadu, Himachal Pradesh has a well-functioning pds, providing not only foodgrain but also pulses and oil and covering both “BPL” (Below Poverty Line) and “APL” (Above Poverty Line) families. Himachal Pradesh has also followed comprehensive principles not only in the provision of essential social services (including schooling facilities, healthcare and child care) but also in the provision of basic amenities such as roads, electricity, drinking water and public transport. For instance, in spite of adverse topography and scattered settlements, 98 per cent of Himachali households had electricity in 2005-6.

It is perhaps not an accident that Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Himachal Pradesh also tend to have the best social indicators among all major Indian states. For instance, a simple index of children’s health, education and nutrition achievements clearly places these three states at the top (Dreze, R. Khera, S. Narayanan, 2007, ‘Early Childhood in India: Facing the Facts’, Indian Journal of Human Development, 1(2), Jul-Dec 2007). Despite wide historical, cultural and political differences, they have converged towards a similar approach to social policy, and the results are much the same too. There is a crucial lesson here for other Indian states, and indeed for the country as a whole.

A Concluding Remark

We hope that the puzzle with which we began is a little clearer now. India’s recent development experience includes both spectacular success as well as massive failure. The growth record is very impressive, and provides an important basis for all-round development, not least by generating more public revenue (about four times as much today, in real terms, as in 1990). But there has also been a failure to ensure that rapid growth translates into better living conditions for the Indian people. It is not that they have not improved at all, but the pace of improvement has been very slow—even slower than in Bangladesh or Nepal. There is probably no other example in the history of world development of an economy growing so fast for so long with such limited results in terms of broad-based social progress.

There is no mystery in this contrast, or in the limited reach of India’s development efforts. Both reflect the nature of policy priorities in this period. But as we have argued, these priorities can change through democratic engagement—as has already happened to some extent in specific states. However, this requires a radical broadening of public discussion in India to development-related matters—rather than keeping it confined to simple comparisons of the growth of the gnp, and naive admiration (implicit or explicit) of the high living standards of a relatively small part of the population. An exaggerated concentration on the lives of the minority of the better-off, fed strongly by media interest, gives an unreal picture of the rosiness of what is happening to Indians in general, and stifles public dialogue of other issues. Imaginative democratic practice, we have argued, is essential for broadening and enhancing India’s development achievements.

Jean Dreze is Visiting Professor, Department of Economics, Allahabad University. Nobel laureate Amartya Sen is Lamont University professor and Professor of Economics and Philosophy at Harvard University.

706 Comments

706 Comments