'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Friday, 18 November 2022

Thursday, 16 June 2022

Why we trust fraudsters

From Enron to Wirecard, elaborate scams can remain undetected long after the warning signs appear. What are investors missing? Tom Straw in The FT

In March 2020, the star English fund manager Alexander Darwall spoke admiringly to the chief executive at one of the largest investments in his award-winning portfolio. “The last set of numbers are fantastic,” he gushed, adding: “This is a crazy situation. People should be looking at your company and saying ‘wow’. I’m delighted, I’m delighted to be a shareholder.”

Seated in a swivel chair at his personal conference table, Markus Braun sounded relaxed. The billionaire technologist was dressed all in black, a turtleneck under his suit like some distant Austrian cousin of the late Steve Jobs, and he had little to say about swirling allegations the company had faked its profits for years. “I am very optimistic,” he offered, when Darwall voiced his hope that the controversy would amount to nothing more than growing pains at a fast expanding company.

“I haven’t sold a single share,” Darwall assured him, doing most of the talking, while also acknowledging how precarious the situation was. The Financial Times had reported in October 2019 that large portions of Wirecard’s sales and profits were fraudulent, and published internal company documents stuffed with the names of fake clients. A six-month “special audit” by the accounting firm KPMG was approaching completion. “If it shows anything that senior people misled, that would be a disaster,” Darwall said.

His assessment proved correct. Three months later the company collapsed like a house of cards, punctuated by a final lie: that €1.9bn of its cash was “missing”. In fact, the money never existed and Wirecard had for years relied on a fraud that was almost farcical in its simplicity: a few friends of the company claimed to manage huge amounts of business for Wirecard, with all the vast profits from these partners said to be collected in special bank accounts overseen by a Manila-based lawyer with a YouTube following. Braun, who claims to be a victim of a protégé with security services connections who masterminded the scheme and then absconded to Belarus, faces a trial this autumn alongside two subordinates that will examine how the final years of the fraud were accomplished.

Left behind in the ashes, however, is a much larger question, one which haunts all victims of such scams: how on earth did they get away with it for so long? Wirecard faces serious questions about the integrity of its accounts since at least 2010. Estimates for losses run to more than €20bn, never mind the reputation of Frankfurt as a financial centre. Why did so many inside and outside the company — a long list of investors, bankers, regulators, prosecutors, auditors and analysts — look at the evidence that Wirecard was too good to be true and decide to trust Braun?

---

In 2019 I worked with whistleblowers to expose Wirecard, using internal documents to show the true source of its spellbinding growth in sales and profit. As I faced Twitter vitriol and accusations I was corrupt, the retired American short-seller Marc Cohodes regularly rang me from wine country on the US west coast to deliver pep talks and describe his own attempts to persuade German journalists to see Wirecard’s true colours. “Keep going Dan. I always say, ‘there’s never just one cockroach in the kitchen’.”

He was right on that point: find one lie and another soon follows. But short-sellers who search for overvalued companies to bet against are unusual, because they go looking for fraud and skulduggery. Most investors are not prosecutors fitting facts into a pattern of guilt: they don’t see a cockroach at all.

Think of Elizabeth Holmes, another aficionado of the black turtleneck, who persuaded a group of experts and well-known investors to back or advise her company, Theranos, based on the claim it had technology able to deliver medical results from an improbably small pinprick of blood. The involvement of reputable people and institutions — including retired general James Mattis, former secretary of state Henry Kissinger and former Wells Fargo chief executive Richard Kovacevich as board members — seemed to confirm that all was well.

Another problem is that complex frauds have a dark magic that is different to, say, “Count” Victor Lustig personally persuading two scrap metal dealers he could sell them a decaying Eiffel Tower in 1925. As Dan Davies wrote in his history of financial scams, Lying for Money, “the way in which most white-collar crime works is by manipulating institutional psychology. That means creating something that looks as much as possible like a normal set of transactions. The drama comes much later, when it all unwinds.”

What such frauds exploit is the highly valuable character of trust in modern economies. We go through life assuming the businesses we encounter are real, confident that there are institutions and processes in place to check that food standards are met or accounts are prepared correctly. Horse meat smugglers, Enron and Wirecard all abused trust in complex systems as a whole. To doubt them was to doubt the entire structure, which is what makes their impact so insidious; frauds degrade faith in the whole system.

Trust means not wasting time on pointless checks. Most deceptions would generally have been caught early on by basic due diligence, “but nobody does confirm the facts. There are just too bloody many of them”, wrote Davies. It makes as much sense for a banker to visit every outpost of a company requiring a loan as it would for the buyer of a pint of milk to inquire after the health of the cow. For instance, by the time John Paulson, one of the world’s most famous and successful hedge fund managers, became the largest shareholder in Canadian-listed Sino Forest, its shares had traded for 15 years. Until the group’s 2011 collapse, few thought of travelling to China to see if its woodlands were there.

---

Yet what stands out in the case of Wirecard are the many attempts to check the actual facts. In 2015 a young American investigator, Susannah Kroeber, tried to knock on the doors at several remote Wirecard locations. Between 2010 and 2015 the company claimed to have grown in a series of leaps and bounds by buying businesses all over Asia for tens of millions of euros apiece. In Laos she found nothing at all, in Cambodia only traces. Wirecard’s reception area in Vietnam was like a school lunchroom; the only furniture was a picnic table for six and an open bicycle lock hung from one of the internal doors, a common security measure usually removed at a business expecting visitors. The inside was dim, with only a handful of people visible and many desks empty. She knew something wasn’t right, but she also told me that while she went half mad looking for non-existent addresses on heat-baked Southeast Asian dirt roads, she had an epiphany: “Who in their right mind would go to these lengths just to check out a stock investment?”

Even when Kroeber’s snapshots of empty offices were gathered into a report for her employer, J Capital Research, and presented to Wirecard investors, the response reflected preconceived expectations: these are reputable people, EY is a good auditor, why would they be lying? The short seller Leo Perry described attending an investor meeting where the report was discussed. A French fund manager responded by reporting his own due diligence. He’d asked his secretary to call Wirecard’s Singapore office, the site of its Asian headquarters, and could happily report that someone there had picked up the phone.

The shareholders reacted at an emotional level, showing how fraud exploits human behaviour. “When you’re invested in the success of something, you want to see it be the best it can be, you don’t pay attention to the finer details that are inconsistent”, says Martina Dove, author of The Psychology of Fraud, Persuasion and Scam Techniques. She adds that social proof and deference to authority, such as expert accounting firms, were powerful forces when used to spread the lies of crooks: “If a friend recommends a builder, you trust that builder because you trust your friend.”

Wirecard’s response, in addition to taking analysts on a tour of hastily well-staffed offices in Asia, was to drape itself in complexity. Like WeWork, the office space provider that presented itself as a technology company (and which wasn’t accused of fraud), Wirecard waved a wand of innovation to make an ordinary business appear extraordinary.

At heart, Wirecard’s legitimate operations processed credit and debit card payments for retailers all over the world. It was a competitive field with many rivals, but Wirecard claimed to have become a European PayPal and more, outpacing the competition with profit margins few could match. Wirecard was “a technology company with a bank as a daughter”, Braun said, one using artificial intelligence and cutting-edge security. As the share price rose, so did Braun’s standing as a technologist who heralded the arrival of a cashless society. Who were mere investors to suggest that the results of this whirligig, with operations in 40 countries, were too good to be true?

It seems to me Wirecard used a similar tactic to the founder of software group Autonomy, Mike Lynch, who charged that critics simply didn’t understand the business. (Lynch has lost a civil fraud trial relating to the $11bn sale of the group, denied any wrongdoing, said he will appeal, and is fighting extradition to the US to face fraud charges. Autonomy’s former CFO was convicted of fraud in separate American proceedings.)

When this publication presented internal documents describing a book cooking operation in Singapore, Wirecard focused on the amounts at stake, which were initially small, rather than the unpunished practices of forgery and money laundering, which were damning.

Then there was the thrall of German officials. Three times, in 2008, 2017, and 2019, the financial market regulator BaFin publicly investigated critics of Wirecard, taken by observers as a signal of support. Indeed, BaFin fell for the big lie when faced with an unenviable choice of circumstances: either foreign journalists and speculators were conspiring to attack Germany’s new technology champion using the pages of a prominent newspaper; or senior executives at a DAX 30 company were lying to prosecutors, as well as some of Germany’s most prestigious banks and investment houses. Acting on a claim by Wirecard that traders knew about an FT story before publication, regulators suspended short selling of the stock to protect the integrity of financial markets.

Proximity to the subject won out, but the German authorities were hardly the first to fail in this way. Their US counterparts ignored the urging of Harry Markopolos to investigate the Ponzi schemer Bernard Madoff, a former chairman of the Nasdaq whose imaginary $65bn fund sent out account statements run off a dot matrix printer.

---

For some long-term investors, to doubt Wirecard was surely to doubt themselves. Darwall first invested in 2007, when the share price was around €9. As it rose more than tenfold, his investment prowess was recognised accordingly, attracting money to the funds he ran for Jupiter Asset Management, and fame. He knew the Wirecard staff, they had provided advice on taking payments for his wife’s holiday rental. Naturally he trusted Braun.

Darwall did not respond to requests for comment made to his firm, Devon Equity Management.

In the buildings beyond the shades of Braun’s office, staff rationalised what didn’t fit. Wirecard was a tech company, yet in early 2016 it suffered a tech disaster. On a quiet Saturday afternoon, running down a list of routine maintenance, a tech guy made a typo. He entered the wrong command when decommissioning a Linux server. Instead of taking out the one machine, he watched with rising panic as it killed all of them, pulling the plug on almost the entire company’s operations without warning.

Customers were in the dark, as email was offline and Wirecard had no weekend helpline, and it took days for services to recover. Following the incident, a small but notable proportion of clients left and new business was put on hold as teams placated those they already had, staff recalled. Yet the pace of growth in the published numbers remained strong.

Martin Osterloh, a salesman at Wirecard for 15 years, put the mismatch between claims and capabilities down to spin. Only after the fall was the extent of Wirecard’s hackers, private detectives, intimidation and legal threats exposed to the light. Haphazard lines of communication, disorganisation and poor record keeping created excuses for middle-ranking Wirecard staff and its supervisory board, stories to tell themselves about a failure to integrate and start-up’s culture of experimentation.

It was perhaps not as hard to believe as we might think. Facebook, which has probed the legal boundaries of surveillance capitalism, famously encouraged staff to “move fast and break things”. Business questions often shade grey before they turn black. As Andrew Fastow said of his own career as a fraudster, “I wasn’t the chief finance officer at Enron, I was the chief loophole officer.”

Braun’s protégé was chief operating officer Jan Marsalek, a mercurial Austrian who constantly travelled and struck deals, with no real team to speak of. Boasting that he only slept “in the air”, he would appear at headquarters from one flight with a copy of Sun-Tzu’s The Art of War tucked under an arm, then leave a few hours later for the next. Questions were met with a shrug, that strange arrangements reflected Marsalek’s “chaotic genius”. As scrutiny intensified in the final 18 months, the fraudulent imitation shifted to problem solving, allowing board members and staff to think they were engaged in procedures to improve governance.

After the collapse I shared pretzels with Osterloh on a snowy day in Munich and he seemed embarrassed by events. He and thousands of others had worked on a real business, until they were summarily fired and learned it lost money hand over fist. Osterloh spoke for many when he said: “I’m like the idiot guy in a movie, I got to meet all these guys. The question arises, why were we so naive? And I can’t really answer that question.”

Saturday, 29 May 2021

Friday, 26 March 2021

Sunday, 22 December 2019

Robert Skidelsky speaks: How and how not to do economics

Sunday, 3 November 2019

How to Keep the Wrong Women out of Your Life | Dr. Shawn T. Smith PsyD | Full Speech

Wednesday, 27 June 2018

Do Writers Care About the Curse of Knowledge?

In A Scandal in Bohemia, Sherlock Holmes, in typical Sherlock Holmes fashion, deduces something outrageous about Watson based on a few stray scratches on his shoes. Watson, in typical Watson fashion, is dumbfounded and asks Holmes to explain his logic. But after listening to Holmes’ explanation, Watson finds himself disappointed and can’t help but laugh. “When I hear you give your reasons,” says Watson, “the thing always appears to me to be so ridiculously simple that I could easily do it myself, though at each successive instance of your reasoning I am baffled until you explain your process.”

With those words, Arthur Conan Doyle might as well have been trying to define the cognitive phenomenon that has come to be called ‘the curse of knowledge’. Vera Tobin, a professor of cognitive science at Case Western Reserve University, Ohio, explains it thus: “the more information we have about something and the more experience we have with it, the harder it is to step outside that experience to appreciate the full implications of not having that privileged information.” Discovered in 1989, the curse of knowledge is now a part of growing family of psychological biases possessed by the human mind. The list includes crowd favourites like hindsight bias and survivor fallacy.

In her book, Elements of Surprise: Our Mental Limits and the Satisfactions of Plot, Tobin aims to illuminate how the purportedly detrimental effects of the curse of knowledge are essential for good storytelling. Just as magicians rely on the predictability of human attention, writers rely on the predictability of human memory or emotion. Writers use these unconscious habits of our minds to make us feel what they want – hope or suspense or edge-of-the-seat panic! These unconscious mental habits or heuristics are reliable enough that techniques to exploit them have existed since antiquity. For example, Bharata’s Natyasastra, which is about 2,000 years old, confidently provides aspiring artists with the ancient equivalent of tips and tricks to get their audience to the appropriate state of aesthetic rapture.

Of course, reading the Natyasastra for these tips and tricks might not be the most efficient use of your time; it’s primarily a book on aesthetic theory. Similarly, aspiring writers might not be the target audience of Tobin’s book. Writers don’t really need to know why their techniques work. They just need to know how to deploy them. Tobin’s book takes these various literary techniques and exhaustively cross-references them with psychological studies that explore their causes and effects.

Elements of Surprise

Vera Tobin

Harvard University Press, 2018

For example, in one section, Tobin connects the cognitive phenomenon of anchoring with the literary technique of “finessing misinformation”. Anchoring is the bias where the mind latches onto an initial piece of information and uses that to “anchor” subsequent discussion. For example, in one study by Dan Ariely, students were divided into two groups and offered money to listen to harsh grating music. One group was offered 10 cents and the other group was offered 90 cents. After playing the harsh music once, they were asked how much they would need to be paid to listen to the music again. The group given 10 cents originally asked for 33 and the group given 90 cents asked for 73. The initial number “anchored” their estimation for what was a fair price. (Think about this the next time you’re at a salary negotiation. The first number put on the table has an outsized effect on what passes for “reasonable”.)

Anchoring is typically studied with quantitative information for obvious reasons but there have been numerous studies showing it is applicable even in qualitative situations. Tobin argues that authors exploit the anchoring effect to slip plot-related misinformation past their audiences. She writes, “Once a possible interpretation of events is introduced at all, it has a degree of persuasive force that derives from a manifestation of the curse of knowledge.” So authors will finesse misinformation to their readers through, for example, the opinions of characters. Or even more subtly, by disguising whether certain statements belong to the narrator or to a character. The more effectively this is done, the more satisfying finally revealing the truth can be.

In another fruitful section, Tobin discusses the value of “presupposition”. In linguistics, presuppositions are apparent truths that are tacitly assumed by some statement or question. By having characters presuppose information, Tobin writes that authors let statements “enter the narrative without explicit comment.”

For example, in the evergreen classic Kung Fu Panda (2008), Po’s father, the goose, is a popular chef. Po dreams of being a warrior, sure, but he’s also genuinely excited about learning the secret ingredient in his father’s Secret Ingredient Soup. This is the presupposition – it presupposes that there’s an ingredient to learn. Of course, in the end, Po’s father reveals that – spoiler alert – there is no special ingredient. But Po’s obvious belief helps slip this information past the audience “without explicit comment” and then the revelation is free to become the cornerstone of Po’s climactic transformation.

But while the marriage of cognitive science and literature is interesting, there is always the lingering question of reproducibility and effect sizes around the studies that Tobin cites throughout the book. For example, in one chapter where she elaborates on the “curse of knowledge”, she cites a 2007 paper by Susan Birch and Paul Bloom on false-belief tasks. In her discussion, she doesn’t mention a 2013 study by Rachel Ryskin and Sarah Brown-Schmidt that reviewed the Birch and Bloom experiments and estimated that “the true effect size to be less than half of that reported in the original findings.”

To be fair, this probably doesn’t really matter a great deal in terms of the general thrust of Tobin’s argument. But it does point at an issue with the process of going from psychology experiments to statements around the truth of how minds actually work, which looms over the entire book.

Thursday, 28 December 2017

I used to think people made rational decisions. But now I know I was wrong

It’s been coming on for a while, so I can’t claim any eureka moment. But something did crystallise this year. What I changed my mind about was people. More specifically, I realised that people cannot be relied upon to make rational choices. We would have fixed global warming by now if we were rational. Instead, there’s a stubborn refusal to let go of the idea that environmental degradation is a “debate” in which there are “two sides”.

Debating is a great way of exploring an issue when there is real room for doubt and nuance. But when a conclusion can be reached simply by assembling a mountain of known facts, debating is just a means of pitting the rational against the irrational.

Humans like to think we are rational. Some of us are more rational than others. But, essentially, we are all slaves to our feelings and emotions. The trick is to realise this, and be sure to guard against it. It’s something that, in the modern world, we are not good at. Authentic emotions are valued over dry, dull authentic evidence at every turn.

I think that as individuality has become fetishised, our belief in our right to make half-formed snap judgments, based on little more than how we feel, has become problematically unchallengeable. When Uma Thurman declared that she would wait for her anger to abate before she spoke about Harvey Weinstein, it was, I believe, in recognition of this tendency to speak first and think later.

Good for her. The value of calm reasoning is not something that one sees acknowledged very often at the moment. Often, the feelings and emotions that form the basis of important views aren’t so very fine. Sometimes humans understand and control their emotions so little that they sooner or later coagulate into a roiling soup of anxiety, fear, sadness, self-loathing, resentment and anger which expresses itself however it can, finding objects to project its hurt and confusion on to. Like immigrants. Or transsexuals. Or liberals. Or Tories. Or women. Or men.

Even if the desire to find living, breathing scapegoats is resisted, untrammelled emotion can result in unwise and self-defeating decisions, devoid of any rationality. Rationality is a tool we have created to govern our emotions. That’s why education, knowledge, information is the cornerstone of democracy. And that’s why despots love ignorance.

Sometimes we can identify and harness the emotions we need to get us through the thing we know, rationally, that we have to do. It’s great when you’re in the zone. Even negative emotions can be used rationally. I, for example, use anger a lot in my work. I’m writing on it at this moment, just as much as I’m writing on a computer. I’ll stop in a moment. I’ll reach for facts to calm myself. I’ll reach for facts to make my emotions seem rational. Or maybe that’s just me. Whatever that means.

‘‘Consciousness’ involves no executive or causal relationship with any of the psychological processes attributed to it'David Oakley and Peter Halligan

It’s a fact that I can find some facts to back up my feelings about people. Just writing that down helps me to feel secure and in control. The irrationality of humans has been considered a fact since the 1970s, when two psychologists, Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, showed that human decisions were often completely irrational, not at all in their own interests and based on “cognitive biases”. Their ideas were a big deal, and also formed the basis of Michael Lewis’s book, The Undoing Project.

More recent research – or more recent theory, to be precise – has rendered even Tversky and Kahneman’s ideas about the unreliability of the human mind overly rational.

Chasing the Rainbow: The Non-Conscious Nature of Being is a research paper from University College London and Cardiff University. Its authors, David Oakley and Peter Halligan, argue “that ‘consciousness’ contains no top-down control processes and that ‘consciousness’ involves no executive, causal, or controlling relationship with any of the familiar psychological processes conventionally attributed to it”.

Which can only mean that even when we think we’re being rational, we’re not even really thinking. That thing we call thinking – we don’t even know what it really is.

When I started out in journalism, opinion columns weren’t a big thing. Using the word “I’ in journalism was frowned upon. The dispassionate dissemination of facts was the goal to be reached for.

Now so much opinion is published, in print and online, and so many people offer their opinions about the opinions, that people in our government feel comfortable in declaring that experts are overrated, and the president of the United States regularly says that anything he doesn’t like is “fake news”.

So, people. They’re a problem. That’s what I’ve decided. I’m part of a big problem. All I can do now is get my message out there.

Wednesday, 29 November 2017

What military incompetence can teach us about Brexit

A fascinating article by Simon Kuper has proposed a parallel between Brexit and the strange cargo cults of Melanesia, when societies suddenly destroy their economic underpinnings in search of a golden age, because they perceive the tribe is in some kind of decline.

It is particularly relevant now that corners of the Conservative party appear to be baying for a non-negotiated Brexit. And unfortunately, as the countdown ticks by, that may well be what they get.

There is another parallel, but it comes from psychology not anthropology. It derives from an influential theory by a former military engineer-turned-psychologist, Norman Dixon. His book, On the Psychology of Military Incompetence, was published in 1976, and has been in print ever since. His ideas may draw too much on Freudian concepts for current tastes, but there are worrying parallels to the phenomenon that he identified: the syndrome that seemed to lie behind so many British military disasters.

His thesis was that the old idea that military incompetence was something to do with stupidity had to be set aside. Not only were the features of incompetence extraordinarily similar from military disaster to military disaster, but the military itself tended to choose people with the same psychological flaws. It led soldiers over the top to disaster, or to a frozen death, as in the Crimea.

These characteristics included arrogant underestimation of the enemy, the inability to learn from experience, resistance to new technologies or new tactics, and an aversion to reconnaissance and intelligence.

Other common themes are great physical bravery but little moral courage, an imperviousness to human suffering, passivity and indecision, and a tendency to lay the blame on others. They tend to have a love of the frontal assault – nothing too clever – and of smartness, precision and the military pecking order.

Dixon also described a tendency to eschew moderate risks for tasks so difficult that failure might seem excusable.

Therein lies the great paradox. To be a successful military commander, you need more flexibility of thought and hierarchy than is encouraged by the traditional military – or the traditional Conservative party, as the xenophobes inch their way into the driving seat.

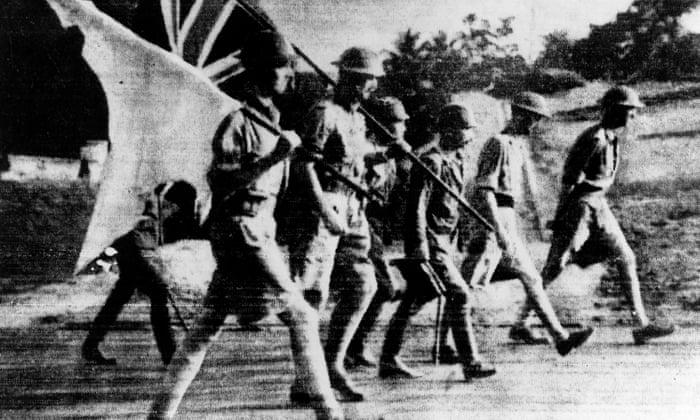

But it was Dixon’s description of the disastrous fall of Singapore in 1942, almost without a fight, because the local command distrusted new tactics and underestimated the Japanese, that really chimes. And his description of too many second-rate officers repeating how they wanted to “teach a lesson to the Japs”.

None of this suggests that Brexit is somehow the wrong strategy, but that the agenda has been wrested by a group of people showing the classic symptoms of the psychology of military incompetence, including a self-satisfied obsession with appearance over reality and pomp over practicality, and a serious tendency to talk about European nations as if they needed to be “taught a lesson”.

Never was imagination and a sophisticated understanding of a changing world so required. Read Dixon, and you begin to worry that the more we hear fighting talk as if the continent were filled with enemies, the more we might expect a hideous capitulation.

Dixon died in 2013, but he did leave behind this advice, originally given by Prince Philip to Sandhurst cadets in 1955: “As you grow older, try not to be afraid of new ideas. New or original ideas can be bad as well as good, but whereas an intelligent man with an open mind can demolish a bad idea by reasoned argument, those who allow their brains to atrophy resort to meaningless catchphrases, to derision and finally to anger in the face of anything new.” Right or wrong, it sounds like we need a few more Brexit mutineers.

Tuesday, 7 February 2017

The hi-tech war on science fraud

One morning last summer, a German psychologist named Mathias Kauff woke up to find that he had been reprimanded by a robot. In an email, a computer program named Statcheck informed him that a 2013 paper he had published on multiculturalism and prejudice appeared to contain a number of incorrect calculations – which the program had catalogued and then posted on the internet for anyone to see. The problems turned out to be minor – just a few rounding errors – but the experience left Kauff feeling rattled. “At first I was a bit frightened,” he said. “I felt a bit exposed.”

Statcheck’s method was relatively simple, more like the mathematical equivalent of a spellchecker than a thoughtful review, but some scientists saw it as a new form of scrutiny and suspicion, portending a future in which the objective authority of peer review would be undermined by unaccountable and uncredentialed critics.

Susan Fiske, the former head of the Association for Psychological Science, wrote an op-ed accusing “self-appointed data police” of pioneering a new “form of harassment”. The German Psychological Society issued a statement condemning the unauthorised use of Statcheck. The intensity of the reaction suggested that many were afraid that the program was not just attributing mere statistical errors, but some impropriety, to the scientists.

The man behind all this controversy was a 25-year-old Dutch scientist named Chris Hartgerink, based at Tilburg University’s Meta-Research Center, which studies bias and error in science. Statcheck was the brainchild of Hartgerink’s colleague Michèle Nuijten, who had used the program to conduct a 2015 study that demonstrated that about half of all papers in psychology journals contained a statistical error. Nuijten’s study was written up in Nature as a valuable contribution to the growing literature acknowledging bias and error in science – but she had not published an inventory of the specific errors it had detected, or the authors who had committed them. The real flashpoint came months later,when Hartgerink modified Statcheck with some code of his own devising, which catalogued the individual errors and posted them online – sparking uproar across the scientific community.

Hartgerink is one of only a handful of researchers in the world who work full-time on the problem of scientific fraud – and he is perfectly happy to upset his peers. “The scientific system as we know it is pretty screwed up,” he told me last autumn. Sitting in the offices of the Meta-Research Center, which look out on to Tilburg’s grey, mid-century campus, he added: “I’ve known for years that I want to help improve it.” Hartgerink approaches his work with a professorial seriousness – his office is bare, except for a pile of statistics textbooks and an equation-filled whiteboard – and he is appealingly earnest about his aims. His conversations tend to rapidly ascend to great heights, as if they were balloons released from his hands – the simplest things soon become grand questions of ethics, or privacy, or the future of science.

“Statcheck is a good example of what is now possible,” he said. The top priority,for Hartgerink, is something much more grave than correcting simple statistical miscalculations. He is now proposing to deploy a similar program that will uncover fake or manipulated results – which he believes are far more prevalent than most scientists would like to admit.

When it comes to fraud – or in the more neutral terms he prefers, “scientific misconduct” – Hartgerink is aware that he is venturing into sensitive territory. “It is not something people enjoy talking about,” he told me, with a weary grin. Despite its professed commitment to self-correction, science is a discipline that relies mainly on a culture of mutual trust and good faith to stay clean. Talking about its faults can feel like a kind of heresy. In 1981, when a young Al Gore led a congressional inquiry into a spate of recent cases of scientific fraud in biomedicine, the historian Daniel Kevles observed that “for Gore and for many others, fraud in the biomedical sciences was akin to pederasty among priests”.

The comparison is apt. The exposure of fraud directly threatens the special claim science has on truth, which relies on the belief that its methods are purely rational and objective. As the congressmen warned scientists during the hearings, “each and every case of fraud serves to undermine the public’s trust in the research enterprise of our nation”.

But three decades later, scientists still have only the most crude estimates of how much fraud actually exists. The current accepted standard is a 2009 study by the Stanford researcher Daniele Fanelli that collated the results of 21 previous surveys given to scientists in various fields about research misconduct. The studies, which depended entirely on scientists honestly reporting their own misconduct, concluded that about 2% of scientists had falsified data at some point in their career.

If Fanelli’s estimate is correct, it seems likely that thousands of scientists are getting away with misconduct each year. Fraud – including outright fabrication, plagiarism and self-plagiarism – accounts for the majority of retracted scientific articles. But, according to RetractionWatch, which catalogues papers that have been withdrawn from the scientific literature, only 684 were retracted in 2015, while more than 800,000 new papers were published. If even just a few of the suggested 2% of scientific fraudsters – which, relying on self-reporting, is itself probably a conservative estimate – are active in any given year, the vast majority are going totally undetected. “Reviewers and editors, other gatekeepers – they’re not looking for potential problems,” Hartgerink said.

But if none of the traditional authorities in science are going to address the problem, Hartgerink believes that there is another way. If a program similar to Statcheck can be trained to detect the traces of manipulated data, and then make those results public, the scientific community can decide for itself whether a given study should still be regarded as trustworthy.

Hartgerink’s university, which sits at the western edge of Tilburg, a small, quiet city in the southern Netherlands, seems an unlikely place to try and correct this hole in the scientific process. The university is best known for its economics and business courses and does not have traditional lab facilities. But Tilburg was also the site of one of the biggest scientific scandals in living memory – and no one knows better than Hartgerink and his colleagues just how devastating individual cases of fraud can be.

In September 2010, the School of Social and Behavioral Science at Tilburg University appointed Diederik Stapel, a promising young social psychologist, as its new dean. Stapel was already popular with students for his warm manner, and with the faculty for his easy command of scientific literature and his enthusiasm for collaboration. He would often offer to help his colleagues, and sometimes even his students, by conducting surveys and gathering data for them.

As dean, Stapel appeared to reward his colleagues’ faith in him almost immediately. In April 2011 he published a paper in Science, the first study the small university had ever landed in that prestigious journal. Stapel’s research focused on what psychologists call “priming”: the idea that small stimuli can affect our behaviour in unnoticed but significant ways. “Could being discriminated against depend on such seemingly trivial matters as garbage on the streets?” Stapel’s paper in Science asked. He proceeded to show that white commuters at the Utrecht railway station tended to sit further away from visible minorities when the station was dirty. Similarly, Stapel found that white people were more likely to give negative answers on a quiz about minorities if they were interviewed on a dirty street, rather than a clean one.

Stapel had a knack for devising and executing such clever studies, cutting through messy problems to extract clean data. Since becoming a professor a decade earlier, he had published more than 100 papers, showing, among other things, that beauty product advertisements, regardless of context, prompted women to think about themselves more negatively, and that judges who had been primed to think about concepts of impartial justice were less likely to make racially motivated decisions.

His findings regularly reached the public through the media. The idea that huge, intractable social issues such as sexism and racism could be affected in such simple ways had a powerful intuitive appeal, and hinted at the possibility of equally simple, elegant solutions. If anything united Stapel’s diverse interests, it was this Gladwellian bent. His studies were often featured in the popular press, including the Los Angeles Times and New York Times, and he was a regular guest on Dutch television programmes.

But as Stapel’s reputation skyrocketed, a small group of colleagues and students began to view him with suspicion. “It was too good to be true,” a professor who was working at Tilburg at the time told me. (The professor, who I will call Joseph Robin, asked to remain anonymous so that he could frankly discuss his role in exposing Stapel.) “All of his experiments worked. That just doesn’t happen.”

A student of Stapel’s had mentioned to Robin in 2010 that some of Stapel’s data looked strange, so that autumn, shortly after Stapel was made Dean, Robin proposed a collaboration with him, hoping to see his methods first-hand. Stapel agreed, and the data he returned a few months later, according to Robin, “looked crazy. It was internally inconsistent in weird ways; completely unlike any real data I had ever seen.” Meanwhile, as the student helped get hold of more datasets from Stapel’s former students and collaborators, the evidence mounted: more “weird data”, and identical sets of numbers copied directly from one study to another.

In August 2011, the whistleblowers took their findings to the head of the department, Marcel Zeelenberg, who confronted Stapel with the evidence. At first, Stapel denied the charges, but just days later he admitted what his accusers suspected: he had never interviewed any commuters at the railway station, no women had been shown beauty advertisements and no judges had been surveyed about impartial justice and racism.

Stapel hadn’t just tinkered with numbers, he had made most of them up entirely, producing entire datasets at home in his kitchen after his wife and children had gone to bed. His method was an inversion of the proper scientific method: he started by deciding what result he wanted and then worked backwards, filling out the individual “data” points he was supposed to be collecting.

On 7 September 2011, the university revealed that Stapel had been suspended. The media initially speculated that there might have been an issue with his latest study – announced just days earlier, showing that meat-eaters were more selfish and less sociable – but the problem went much deeper. Stapel’s students and colleagues were about to learn that his enviable skill with data was, in fact, a sham, and his golden reputation, as well as nearly a decade of results that they had used in their own work, were built on lies.

Chris Hartgerink was studying late at the library when he heard the news. The extent of Stapel’s fraud wasn’t clear by then, but it was big. Hartgerink, who was then an undergraduate in the Tilburg psychology programme, felt a sudden disorientation, a sense that something solid and integral had been lost. Stapel had been a mentor to him, hiring him as a research assistant and giving him constant encouragement. “This is a guy who inspired me to actually become enthusiastic about research,” Hartgerink told me. “When that reason drops out, what remains, you know?”

Hartgerink wasn’t alone; the whole university was stunned. “It was a really difficult time,” said one student who had helped expose Stapel. “You saw these people on a daily basis who were so proud of their work, and you know it’s just based on a lie.” Even after Stapel resigned, the media coverage was relentless. Reporters roamed the campus – first from the Dutch press, and then, as the story got bigger, from all over the world.

On 9 September, just two days after Stapel was suspended, the university convened an ad-hoc investigative committee of current and former faculty. To help determine the true extent of Stapel’s fraud, the committee turned to Marcel van Assen, a statistician and psychologist in the department. At the time, Van Assen was growing bored with his current research, and the idea of investigating the former dean sounded like fun to him. Van Assen had never much liked Stapel, believing that he relied more on the force of his personality than reason when running the department. “Some people believe him charismatic,” Van Assen told me. “I am less sensitive to it.”

Van Assen – who is 44, tall and rangy, with a mop of greying, curly hair – approaches his work with relentless, unsentimental practicality. When speaking, he maintains an amused, half-smile, as if he is joking. He once told me that to fix the problems in psychology, it might be simpler to toss out 150 years of research and start again; I’m still not sure whether or not he was serious.

To prove misconduct, Van Assen said, you must be a pitbull: biting deeper and deeper, clamping down not just on the papers, but the datasets behind them, the research methods, the collaborators – using everything available to bring down the target. He spent a year breaking down the 45 studies Stapel produced at Tilburg and cataloguing their individual aberrations, noting where the effect size – a standard measure of the difference between the two groups in an experiment –seemed suspiciously large, where sequences of numbers were copied, where variables were too closely related, or where variables that should have moved in tandem instead appeared adrift.

The committee released its final report in October 2012 and, based largely on its conclusions, 55 of Stapel’s publications were officially retracted by the journals that had published them. Stapel also returned his PhD to the University of Amsterdam. He is, by any measure, one of the biggest scientific frauds of all time. (RetractionWatch has him third on their all-time retraction leaderboard.) The committee also had harsh words for Stapel’s colleagues, concluding that “from the bottom to the top, there was a general neglect of fundamental scientific standards”. “It was a real blow to the faculty,” Jacques Hagenaars, a former professor of methodology at Tilburg, who served on the committee, told me.

By extending some of the blame to the methods and attitudes of the scientists around Stapel, the committee situated the case within a larger problem that was attracting attention at the time, which has come to be known as the “replication crisis”. For the past decade, the scientific community has been grappling with the discovery that many published results cannot be reproduced independently by other scientists – in spite of the traditional safeguards of publishing and peer-review – because the original studies were marred by some combination of unchecked bias and human error.

After the committee disbanded, Van Assen found himself fascinated by the way science is susceptible to error, bias, and outright fraud. Investigating Stapel had been exciting, and he had no interest in returning to his old work. Van Assen had also found a like mind, a new professor at Tilburg named Jelte Wicherts, who had a long history working on bias in science and who shared his attitude of upbeat cynicism about the problems in their field. “We simply agree, there are findings out there that cannot be trusted,” Van Assen said. They began planning a new sort of research group: one that would investigate the very practice of science.

Van Assen does not like assigning Stapel too much credit for the creation of the Meta-Research Center, which hired its first students in late 2012, but there is an undeniable symmetry: he and Wicherts have created, in Stapel’s old department, a platform to investigate the sort of “sloppy science” and misconduct that very department had been condemned for.

Hartgerink joined the group in 2013. “For many people, certainly for me, Stapel launched an existential crisis in science,” he said. After Stapel’s fraud was exposed, Hartgerink struggled to find “what could be trusted” in his chosen field. He began to notice how easy it was for scientists to subjectively interpret data – or manipulate it. For a brief time he considered abandoning a future in research and joining the police.

There are probably several very famous papers that have fake data, and very famous people who have done it

Van Assen, who Hartgerink met through a statistics course, helped put him on another path. Hartgerink learned that a growing number of scientists in every field were coming to agree that the most urgent task for their profession was to establish what results and methods could still be trusted – and that many of these people had begun to investigate the unpredictable human factors that, knowingly or not, knocked science off its course. What was more, he could be a part of it. Van Assen offered Hartgerink a place in his yet-unnamed research group. All of the current projects were on errors or general bias, but Van Assen proposed they go out and work closer to the fringes, developing methods that could detect fake data in published scientific literature.

“I’m not normally an expressive person,” Hartgerink told me. “But I said: ‘Hell, yes. Let’s do that.’”

Hartgerink and Van Assen believe not only that most scientific fraud goes undetected, but that the true rate of misconduct is far higher than 2%. “We cannot trust self reports,” Van Assen told me. “If you ask people, ‘At the conference, did you cheat on your fiancee?’ – people will very likely not admit this.”

Uri Simonsohn, a psychology professor at University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School who gained notoriety as a “data vigilante” for exposing two serious cases of fraud in his field in 2012, believes that as much as 5% of all published research contains fraudulent data. “It’s not only in the periphery, it’s not only in the journals people don’t read,” he told me. “There are probably several very famous papers that have fake data, and very famous people who have done it.”

But as long as it remains undiscovered, there is a tendency for scientists to dismiss fraud in favour of more widely documented – and less seedy – issues. Even Arturo Casadevall, an American microbiologist who has published extensively on the rate, distribution, and detection of fraud in science, told me that despite his personal interest in the topic, my time would be better served investigating the broader issues driving the replication crisis. Fraud, he said, was “probably a relatively minor problem in terms of the overall level of science”.

This way of thinking goes back at least as far as scientists have been grappling with high-profile cases of misconduct. In 1983, Peter Medawar, the British immunologist and Nobel laureate, wrote in the London Review of Books: “The number of dishonest scientists cannot, of course, be known, but even if they were common enough to justify scary talk of ‘tips of icebergs’, they have not been so numerous as to prevent science’s having become the most successful enterprise (in terms of the fulfilment of declared ambitions) that human beings have ever engaged upon.”

From this perspective, as long as science continues doing what it does well – as long as genes are sequenced and chemicals classified and diseases reliably identified and treated – then fraud will remain a minor concern. But while this may be true in the long run, it may also be dangerously complacent. Furthermore, scientific misconduct can cause serious harm, as, for instance, in the case of patients treated by Paolo Macchiarini, a doctor at Karolinska Institute in Sweden who allegedly misrepresented the effectiveness of an experimental surgical procedure he had developed. Macchiarini is currently being investigated by a Swedish prosecutor after several of the patients who received the procedure later died.

Even in the more mundane business of day-to-day research, scientists are constantly building on past work, relying on its solidity to underpin their own theories. If misconduct really is as widespread as Hartgerink and Van Assen think, then false results are strewn across scientific literature, like unexploded mines that threaten any new structure built over them. At the very least, if science is truly invested in its ideal of self-correction, it seems essential to know the extent of the problem.

But there is little motivation within the scientific community to ramp up efforts to detect fraud. Part of this has to do with the way the field is organised. Science isn’t a traditional hierarchy, but a loose confederation of research groups, institutions, and professional organisations. Universities are clearly central to the scientific enterprise, but they are not in the business of evaluating scientific results, and as long as fraud doesn’t become public they have little incentive to go after it. There is also the questionable perception, although widespread in the scientific community, that there are already measures in place that preclude fraud. When Gore and his fellow congressmen held their hearings 35 years ago, witnesses routinely insisted that science had a variety of self-correcting mechanisms, such as peer-review and replication. But, as the science journalists William Broad and Nicholas Wade pointed out at the time, the vast majority of cases of fraud are actually exposed by whistleblowers, and that holds true to this day.

And so the enormous task of keeping science honest is left to individual scientists in the hope that they will police themselves, and each other. “Not only is it not sustainable,” said Simonsohn, “it doesn’t even work. You only catch the most obvious fakers, and only a small share of them.” There is also the problem of relying on whistleblowers, who face the thankless and emotionally draining prospect of accusing their own colleagues of fraud. (“It’s like saying someone is a paedophile,” one of the students at Tilburg told me.) Neither Simonsohn nor any of the Tilburg whistleblowers I interviewed said they would come forward again. “There is no way we as a field can deal with fraud like this,” the student said. “There has to be a better way.”

In the winter of 2013, soon after Hartgerink began working with Van Assen, they began to investigate another social psychology researcher who they noticed was reporting suspiciously large effect sizes, one of the “tells” that doomed Stapel. When they requested that the researcher provide additional data to verify her results, she stalled – claiming that she was undergoing treatment for stomach cancer. Months later, she informed them that she had deleted all the data in question. But instead of contacting the researcher’s co-authors for copies of the data, or digging deeper into her previous work, they opted to let it go.

They had been thoroughly stonewalled, and they knew that trying to prosecute individual cases of fraud – the “pitbull” approach that Van Assen had taken when investigating Stapel – would never expose more than a handful of dishonest scientists. What they needed was a way to analyse vast quantities of data in search of signs of manipulation or error, which could then be flagged for public inspection without necessarily accusing the individual scientists of deliberate misconduct. After all, putting a fence around a minefield has many of the same benefits as clearing it, with none of the tricky business of digging up the mines.

As Van Assen had earlier argued in a letter to the journal Nature, the traditional approach to investigating other scientists was needlessly fraught – since it combined the messy task of proving that a researcher had intended to commit fraud with a much simpler technical problem: whether the data underlying their results was valid. The two issues, he argued, could be separated.

Scientists can commit fraud in a multitude of ways. In 1974, the American immunologist William Summerlin famously tried to pass a patch of skin on a mouse darkened with permanent marker pen as a successful interspecies skin-graft. But most instances are more mundane: the majority of fraud cases in recent years have emerged from scientists either falsifying images – deliberately mislabelling scans and micrographs – or fabricating or altering their recorded data. And scientists have used statistical tests to scrutinise each other’s data since at least the 1930s, when Ronald Fisher, the father of biostatistics, used a basic chi-squared test to suggest that Gregor Mendel, the father of genetics, had cherrypicked some of his data.

In 2014, Hartgerink and Van Assen started to sort through the variety of tests used in ad-hoc investigations of fraud in order to determine which were powerful and versatile enough to reliably detect statistical anomalies across a wide range of fields. After narrowing down a promising arsenal of tests, they hit a tougher problem. To prove that their methods work, Hartgerink and Van Assen have to show they can reliably distinguish false from real data. But research misconduct is relatively uncharted territory. Only a handful of cases come to light each year – a dismally small sample size – so it’s hard to get an idea of what constitutes “normal” fake data, what its features and particular quirks are. Hartgerink devised a workaround, challenging other academics to produce simple fake datasets, a sort of game to see if they could come up with data that looked real enough to fool the statistical tests, with an Amazon gift card as a prize.

By 2015, the Meta-Research group had expanded to seven researchers, and Hartgerink was helping his colleagues with a separate error-detection project that would become Statcheck. He was pleased with the study that Michèle Nuitjen published that autumn, which used Statcheck to show that something like half of all published psychology papers appeared to contain calculation errors, but as he tinkered with the program and the database of psychology papers they had assembled, he found himself increasingly uneasy about what he saw as the closed and secretive culture of science.

When scientists publish papers in journals, they release only the data they wish to share. Critical evaluation of the results by other scientists – peer review – takes place in secret and the discussion is not released publicly. Once a paper is published, all comments, concerns, and retractions must go through the editors of the journal before they reach the public. There are good, or at least defensible, arguments for all of this. But Hartgerink is part of an increasingly vocal group that believes that the closed nature of science, with authority resting in the hands of specific gatekeepers – journals, universities, and funders – is harmful, and that a more open approach would better serve the scientific method.

Hartgerink realised that with a few adjustments to Statcheck, he could make public all the statistical errors it had exposed. He hoped that this would shift the conversation away from talk of broad, representative results – such as the proportion of studies that contained errors – and towards a discussion of the individual papers and their mistakes. The critique would be complete, exhaustive, and in the public domain, where the authors could address it; everyone else could draw their own conclusions.

In August 2016, with his colleagues’ blessing, he posted the full set of Statcheck results publicly on the anonymous science message board PubPeer. At first there was praise on Twitter and science blogs, which skew young and progressive – and then, condemnations, largely from older scientists, who feared an intrusive new world of public blaming and shaming. In December, after everyone had weighed in, Nature, a bellwether of mainstream scientific thought for more than a century, cautiously supported a future of automated scientific scrutiny in an editorial that addressed the Statcheck controversy without explicitly naming it. Its conclusion seemed to endorse Hartgerink’s approach, that “criticism itself must be embraced”.

In the same month, the Office of Research Integrity (ORI), an obscure branch of the US National Institutes of Health, awarded Hartgerink a small grant – about $100,000 – to pursue new projects investigating misconduct, including the completion of his program to detect fabricated data. For Hartgerink and Van Assen, who had not received any outside funding for their research, it felt like vindication.

Yet change in science comes slowly, if at all, Van Assen reminded me. The current push for more open and accountable science, of which they are a part, has “only really existed since 2011”, he said. It has captured an outsize share of the science media’s attention, and set laudable goals, but it remains a small, fragile outpost of true believers within the vast scientific enterprise. “I have the impression that many scientists in this group think that things are going to change.” Van Assen said. “Chris, Michèle, they are quite optimistic. I think that’s bias. They talk to each other all the time.”

When I asked Hartgerink what it would take to totally eradicate fraud from the scientific process, he suggested that scientists make all of their data public; register the intentions of their work before conducting experiments, to prevent post-hoc reasoning, and that they have their results checked by algorithms during and after the publishing process.

To any working scientist – currently enjoying nearly unprecedented privacy and freedom for a profession that is in large part publicly funded – Hartgerink’s vision would be an unimaginably draconian scientific surveillance state. For his part, Hartgerink believes the preservation of public trust in science requires nothing less – but in the meantime, he intends to pursue this ideal without the explicit consent of the entire scientific community, by investigating published papers and making the results available to the public.

Even scientists who have done similar work uncovering fraud have reservations about Van Assen and Hartgerink’s approach. In January, I met with Dr John Carlisle and Dr Steve Yentis at an anaesthetics conference that took place in London, near Westminster Abbey. In 2012, Yentis, then the editor of the journal Anaesthesia, asked Carlisle to investigate data from a researcher named Yoshitaka Fujii, who the community suspected was falsifying clinical trials. In time, Carlisle demonstrated that 168 of Fujii’s trials contained dubious statistical results. Yentis and the other journal editors contacted Fujii’s employers, who launched a full investigation. Fujii currently sits at the top of the RetractionWatch leaderboard with 183 retracted studies. By sheer numbers he is the biggest scientific fraud in recorded history.

You’re saying to a person, ‘I think you’re a liar.’ How many fraudulent papers are worth one false accusation?

Carlisle, who, like Van Assen, found that he enjoyed the detective work (“it takes a certain personality, or personality disorder”, he said), showed me his latest project, a larger-scale analysis of the rate of suspicious clinical trial results across multiple fields of medicine. He and Yentis discussed their desire to automate these statistical tests – which, in theory, would look a lot like what Hartgerink and Van Assen are developing – but they have no plans to make the results public; instead they envision that journal editors might use the tests to screen incoming articles for signs of possible misconduct.

“It is an incredibly difficult balance,” said Yentis, “you’re saying to a person, ‘I think you’re a liar.’ We have to decide how many fraudulent papers are worth one false accusation. How many is too many?”

With the introduction of programs such as Statcheck, and the growing desire to conduct as much of the critical conversation as possible in public view, Yentis expects a stormy reckoning with those very questions. “That’s a big debate that hasn’t happened,” he said, “and it’s because we simply haven’t had the tools.”

For all their dispassionate distance, when Hartgerink and Van Assen say that they are simply identifying data that “cannot be trusted”, they mean flagging papers and authors that fail their tests. And, as they learned with Statcheck, for many scientists, that will be indistinguishable from an accusation of deceit. When Hartgerink eventually deploys his fraud-detection program, it will flag up some very real instances of fraud, as well as many unintentional errors and false positives – and present all of the results in a messy pile for the scientific community to sort out. Simonsohn called it “a bit like leaving a loaded gun on a playground”.

When I put this question to Van Assen, he told me it was certain that some scientists would be angered or offended by having their work and its possible errors exposed and discussed. He didn’t want to make anyone feel bad, he said – but he didn’t feel bad about it. Science should be about transparency, criticism, and truth.

“The problem, also with scientists, is that people think they are important, they think they have a special purpose in life,” he said. “Maybe you too. But that’s a human bias. I think when you look at it objectively, individuals don’t matter at all. We should only look at what is good for science and society.”

Saturday, 7 January 2017

How to keep your resolutions (clue: it's not all about willpower)

It’s hard to think of a situation in which it wouldn’t be extremely useful to have more willpower. For a start, your New Year’s resolutions would no longer be laughably short-lived. You could stop yourself spending all day on social media, spiralling into despair at the state of the world, yet also summon the self-discipline to do something about it by volunteering or donating to charity. And with more “political will”, which is really just willpower writ large, we could forestall the worst consequences of climate change, or stop quasi-fascist confidence tricksters from getting elected president. In short, if psychologists could figure out how to reliably build and sustain willpower, we’d be laughing.

Unfortunately, though, 2016 was the year in which psychologists had to admit they’d figured out no such thing, and that much of what they thought they knew about willpower was probably wrong. Changing your habits is certainly doable, but “more willpower” may not be the answer after all.

The received wisdom, for nearly two decades, was that willpower is like a muscle. That means you can strengthen it through regular use, but also that you can tire it out, so that expending willpower in one way (for example, by forcing yourself to work when you’d rather be checking Facebook) means there’ll be less left over for other purposes (such as resisting the lure of a third pint after work). In a landmark 1998 study, the social psychologist Roy Bauermeister and his colleagues baked a batch of chocolate cookies and served them alongside a bowl of radishes. They brought two groups of subjects into the lab, instructing each to eat only cookies or only radishes; their reasoning was that it would take self-discipline for the radish-eaters to resist the cookies. In the second stage of the experiment, participants were given puzzles to solve, not realising that they were actually unsolvable. The cookie-eaters plugged away at the puzzles for an average of 19 minutes each, while the radish-eaters gave up after eight, their willpower presumably already eroded by resisting the cookies.

Thus was born the theory of “ego depletion”, which holds that willpower is a limited resource. Pick your New Year resolutions sparingly, otherwise they’ll undermine each other. Your plan to meditate for 20 minutes each morning may actively obstruct your plan to learn Spanish, and vice versa, so you end up achieving neither.

Except willpower probably isn’t like a muscle after all: in recent years, attempts to reproduce the original results have failed, part of a wider credibility crisis in psychology. Meanwhile, a new consensus has begun to gain ground: that willpower isn’t a limited resource, but believing that it is makes you less likely to follow through on your plans.

Some scholars argue that willpower is better understood as being like an emotion: a feeling that comes and goes, rather unpredictably, and that you shouldn’t expect to be able to force, just as you can’t force yourself to feel happy. And, like happiness, its chronic absence may be a warning that you’re on the wrong track. If a relationship reliably made you miserable, you might conclude that it wasn’t the relationship for you. Likewise, if you repeatedly fail to summon the willpower for a certain behaviour, it may be time to accept the fact: perhaps getting better at cooking, or learning to enjoy yoga, just isn’t on the cards for you, and you’d be better advised to focus on changes that truly inspire you. “If you decide you’re going to fight cravings, fight thoughts, fight emotions, you put all your energy and attention into trying to change the inner experiences,” the willpower researcher Kelly McGonigal has argued. And people who do that “tend to become more stuck, and more overwhelmed.” Instead, ask what changes you’d genuinely enjoy having made a year from now, as opposed to those you feel you ought to make.

Lurking behind all this, though, is a more unsettling question: does willpower even exist? McGonigal defines people with willpower as those who demonstrate “the ability to do what matters most, even when it’s difficult, or when some part of [them] doesn’t want to”. Willpower, then, is a word ascribed to people who manage to do what they said they were going to do: it’s a judgment about their behaviour. But it doesn’t follow that willpower is a thing in itself, a substance or resource you either possess or you don’t, like money or muscle strength. Rather than “How can I build my willpower?”, it may be better to ask: “How can I make it more likely that I’ll do what I plan to do?”

One tactic is to manipulate your environment in such a way that willpower becomes less important. If you don’t keep your credit card in your wallet or handbag, it’ll be difficult to use it for unwise impulse purchases; if money is automatically transferred from your current account to a savings account the day you’re paid, your goal of saving won’t rely exclusively on strength of character. Then there’s a technique known as “strategic pre-commitment”: tell a friend about your plan, and the risk of mild public shame may help keep you on track. (Better yet, give them a cheque made out to an organisation you hate, and make them promise to donate it if you fail.) Use whatever tricks happen to fit your personality: the comedian Jerry Seinfeld famously marked an X on a wallchart for every day he managed to write, and soon became unwilling to break the chain of Xs. And exploit the power of “if-then plans”, which are backed by numerous research studies: think through the day ahead, envisaging the specific scenarios in which you might find yourself, and the specific ways you intend to respond when you do. (For example, you might decide that as soon as you feel sleepy after 10pm, you’ll go directly to bed; or that you’ll always put on your running shoes the moment you get home from work.)

The most important boost to your habit-changing plans, though, may lie not in any individual strategy, but in letting go of the idea of “willpower” altogether. If the word doesn’t really refer to an identifiable thing, there’s no need to devote energy to fretting over your lack of it. Behaviour change becomes a far more straightforward matter of assembling a toolbox of tricks that, in combination, should steer you well. Best of all, you’ll no longer be engaged in a battle with your own psyche: you can stop trying to “find the willpower” to live a healthier/kinder/less stressful/more high-achieving life – and just focus on living it instead.

Thursday, 22 September 2016

Why bad science persists?

Wind the clock forward half a century and little has changed. In a new paper, this time published in Royal Society Open Science, two researchers, Paul Smaldino of the University of California, Merced, and Richard McElreath at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, in Leipzig, show that published studies in psychology, neuroscience and medicine are little more powerful than in Cohen’s day.

They also offer an explanation of why scientists continue to publish such poor studies. Not only are dodgy methods that seem to produce results perpetuated because those who publish prodigiously prosper—something that might easily have been predicted. But worryingly, the process of replication, by which published results are tested anew, is incapable of correcting the situation no matter how rigorously it is pursued.

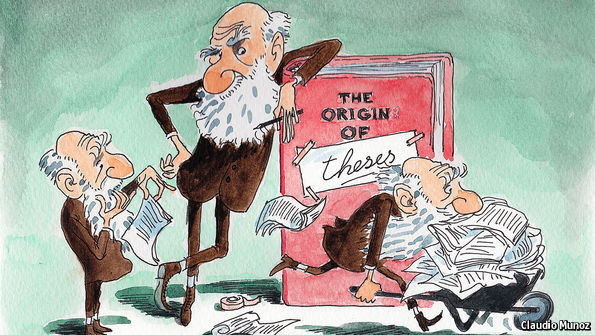

The preservation of favoured places

First, Dr Smaldino and Dr McElreath calculated that the average power of papers culled from 44 reviews published between 1960 and 2011 was about 24%. This is barely higher than Cohen reported, despite repeated calls in the scientific literature for researchers to do better. The pair then decided to apply the methods of science to the question of why this was the case, by modelling the way scientific institutions and practices reproduce and spread, to see if they could nail down what is going on.

They focused in particular on incentives within science that might lead even honest researchers to produce poor work unintentionally. To this end, they built an evolutionary computer model in which 100 laboratories competed for “pay-offs” representing prestige or funding that result from publications. They used the volume of publications to calculate these pay-offs because the length of a researcher’s CV is a known proxy of professional success. Labs that garnered more pay-offs were more likely to pass on their methods to other, newer labs (their “progeny”).

Some labs were better able to spot new results (and thus garner pay-offs) than others. Yet these labs also tended to produce more false positives—their methods were good at detecting signals in noisy data but also, as Cohen suggested, often mistook noise for a signal. More thorough labs took time to rule these false positives out, but that slowed down the rate at which they could test new hypotheses. This, in turn, meant they published fewer papers.

In each cycle of “reproduction”, all the laboratories in the model performed and published their experiments. Then one—the oldest of a randomly selected subset—“died” and was removed from the model. Next, the lab with the highest pay-off score from another randomly selected group was allowed to reproduce, creating a new lab with a similar aptitude for creating real or bogus science.

Sharp-eyed readers will notice that this process is similar to that of natural selection, as described by Charles Darwin, in “The Origin of Species”. And lo! (and unsurprisingly), when Dr Smaldino and Dr McElreath ran their simulation, they found that labs which expended the least effort to eliminate junk science prospered and spread their methods throughout the virtual scientific community.

Their next result, however, was surprising. Though more often honoured in the breach than in the execution, the process of replicating the work of people in other labs is supposed to be one of the things that keeps science on the straight and narrow. But the two researchers’ model suggests it may not do so, even in principle.

Replication has recently become all the rage in psychology. In 2015, for example, over 200 researchers in the field repeated 100 published studies to see if the results of these could be reproduced (only 36% could). Dr Smaldino and Dr McElreath therefore modified their model to simulate the effects of replication, by randomly selecting experiments from the “published” literature to be repeated.

A successful replication would boost the reputation of the lab that published the original result. Failure to replicate would result in a penalty. Worryingly, poor methods still won—albeit more slowly. This was true in even the most punitive version of the model, in which labs received a penalty 100 times the value of the original “pay-off” for a result that failed to replicate, and replication rates were high (half of all results were subject to replication efforts).

The researchers’ conclusion is therefore that when the ability to publish copiously in journals determines a lab’s success, then “top-performing laboratories will always be those who are able to cut corners”—and that is regardless of the supposedly corrective process of replication.

Ultimately, therefore, the way to end the proliferation of bad science is not to nag people to behave better, or even to encourage replication, but for universities and funding agencies to stop rewarding researchers who publish copiously over those who publish fewer, but perhaps higher-quality papers. This, Dr Smaldino concedes, is easier said than done. Yet his model amply demonstrates the consequences for science of not doing so.

Wednesday, 24 August 2016

How tricksters make you see what they want you to see

By David Robson in the BBC

Could you be fooled into “seeing” something that doesn’t exist?

Matthew Tompkins, a magician-turned-psychologist at the University of Oxford, has been investigating the ways that tricksters implant thoughts in people’s minds. With a masterful sleight of hand, he can make a poker chip disappear right in front of your eyes, or conjure a crayon out of thin air.

Although interesting in themselves, the first three videos are really a warm-up for this more ambitious illusion, in which Tompkins tries to plant an image in the participant’s minds using the power of suggestion alone.

Around a third of his participants believed they had seen Tompkins take an object from the pot and tuck it into his hand – only to make it disappear later on. In fact, his fingers were always empty, but his clever pantomiming created an illusion of a real, visible object.

How is that possible? Psychologists have long known that the brain acts like an expert art restorer, touching up the rough images hitting our retina according to context and expectation. This “top-down processing” allows us to build a clear picture from the barest of details (such as this famous picture of the “Dalmatian in the snow”). It’s the reason we can make out a face in the dark, for instance. But occasionally, the brain may fill in too many of the gaps, allowing expectation to warp a picture so that it no longer reflects reality. In some ways, we really do see what we want to see.

This “top-down processing” is reflected in measures of brain activity, and it could easily explain the phantom vanish trick. The warm-up videos, the direction of his gaze, and his deft hand gestures all primed the participants’ brains to see the object between his fingers, and for some participants, this expectation overrode the reality in front of their eyes.